Trans-Splicing Group I Introns: From RNA Repair to Programmable Biocomputing

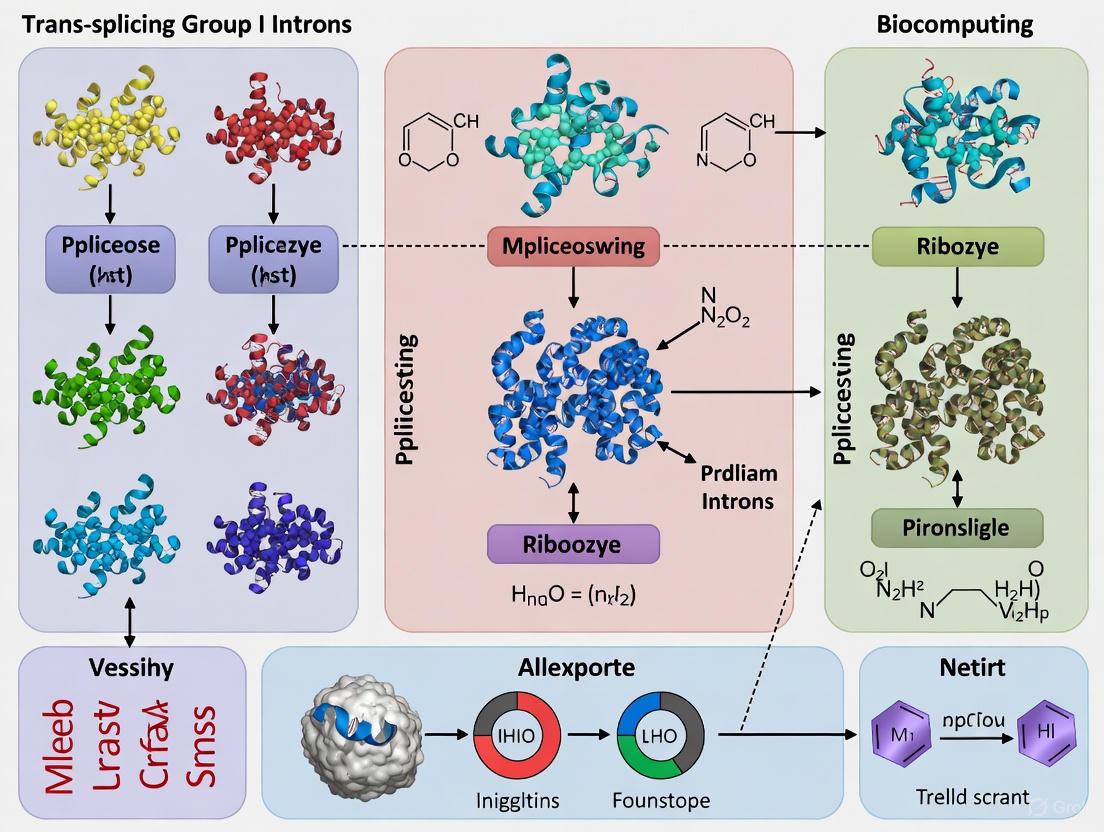

This article explores the transformative potential of trans-splicing group I intron ribozymes as powerful tools for synthetic biology and biocomputing.

Trans-Splicing Group I Introns: From RNA Repair to Programmable Biocomputing

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of trans-splicing group I intron ribozymes as powerful tools for synthetic biology and biocomputing. We cover foundational mechanisms, from their natural self-splicing and mobility to their engineering into trans-splicing devices. The core of the discussion focuses on cutting-edge methodological applications, including the design of complex genetic circuits for cellular logic computation and therapeutic mRNA repair. We also address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhancing splicing efficiency and specificity, and provide a comparative validation of ribozymes from different species like Tetrahymena and Azoarcus. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness RNA-based systems for advanced biomedical applications and sophisticated cellular programming.

The Architectural Blueprint: Understanding Group I Intron Structure and Native Function

Group I introns are a distinct class of large, self-splicing ribozymes—catalytic RNA molecules—that excise themselves from mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA precursors through an autocatalytic process [1] [2]. The landmark discovery of the first group I intron in the ribosomal RNA of Tetrahymena thermophila in the early 1980s fundamentally altered our understanding of RNA's biological role, revealing that RNA could possess enzymatic activity independent of proteins [2] [3]. These genetic elements are characterized by their ability to perform splicing via two sequential transesterification reactions, requiring no spliceosome [1]. Ranging in size from approximately 250 to 500 nucleotides, group I introns are found across the tree of life, present in bacteria, bacteriophages, eukaryotic nuclei, and the organelles of lower eukaryotes and plants [1] [4] [5]. Their sporadic phylogenetic distribution and complex evolutionary history, featuring both vertical inheritance and lateral transfer, make them fascinating subjects for studying RNA evolution and mobility [4] [6].

For biocomputing research, group I introns present a compelling platform as naturally occurring, programmable RNA catalysts. Their ability to be engineered for trans-splicing reactions, where the ribozyme acts on a separate substrate RNA molecule, opens avenues for developing synthetic biological circuits and RNA-based computing devices [7] [3]. The precise, sequence-specific recognition and modification of RNA substrates by engineered group I ribozymes can be harnessed to create logical gates, sensors, and signal amplifiers within living cells, forming the foundation of novel biocomputing systems.

Structural and Mechanistic Hallmarks

Conserved RNA Architecture

The catalytic proficiency of group I introns stems from a highly conserved core tertiary structure, despite significant variation at the primary sequence level [1] [2]. The core secondary structure consists of up to ten paired regions (P1-P10) that fold into two primary domains [1] [5]. The P4-P6 domain (comprising P5, P4, P6, and P6a helices) forms a structural scaffold, while the P3-P9 domain (including P8, P3, P7, and P9 helices) constitutes the catalytic center [1]. Short, conserved sequence elements (P, Q, R, and S) form long-range pairing interactions (P-Q and R-S) that are critical for maintaining the active architecture of the ribozyme core [5].

Table 1: Structural Domains of Group I Intron Ribozymes

| Domain | Structural Elements | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Domain (P4-P6) | P5, P4, P6, P6a helices | Provides structural framework and stability |

| Catalytic Domain (P3-P9) | P8, P3, P7, P9 helices | Contains active site for splicing catalysis |

| Substrate Domain | P1 and P10 helices | Recognizes and binds 5' and 3' splice sites |

Based on variations in their secondary structure configurations and peripheral elements, group I introns are classified into five main subgroups (IA, IB, IC, ID, IE), which are further divided into at least 17 specific subtypes [2]. This structural diversity reflects the evolutionary adaptability of the core ribozyme scaffold.

The Splicing Mechanism

Group I intron splicing proceeds via two consecutive transesterification reactions that require no external energy source [1] [3]. The process is initiated when an exogenous guanosine nucleotide (exoG) docks into the G-binding site located in the P7 helix [1] [5]. The 3'-OH group of this guanosine acts as a nucleophile, attacking the phosphodiester bond at the 5' splice site within the P1 helix. This first step results in the exoG becoming covalently attached to the 5' end of the intron and liberates the upstream exon with a free 3'-OH group [3].

For the second step, the terminal guanosine of the intron (ωG) displaces the exoG and occupies the G-binding site. The free 3'-OH of the upstream exon then attacks the phosphodiester bond at the 3' splice site (defined by the P10 helix), leading to exon ligation and release of the linear intron RNA [1] [5]. The reaction is catalyzed by a two-metal-ion mechanism similar to that used by protein polymerases and phosphatases, with magnesium ions playing critical roles in stabilizing transition states and activating nucleophiles [1] [5].

Figure 1: The Two-Step Transesterification Mechanism of Group I Intron Splicing. The process is initiated by an exogenous guanosine (exoG) and results in precise exon ligation and intron excision.

Distribution and Evolutionary Dynamics

Phylogenetic Distribution

Group I introns display a widespread but highly sporadic distribution across the tree of life [4]. In bacteria, they are found in tRNA, rRNA, and occasionally protein-coding genes, though their occurrence appears more limited compared to lower eukaryotes [1] [5]. Bacterial group I introns are particularly prevalent in cyanobacteria and Gram-positive bacteria, and they are also found in various bacteriophages that infect these organisms [1]. In eukaryotic microorganisms, including fungi, algae, and protists, group I introns frequently interrupt nuclear rRNA genes as well as mitochondrial and chloroplast genes [2] [4]. The nuclear rDNA of myxomycetes (plasmodial slime molds) represents an especially rich reservoir of diverse group I introns, with some species like Diderma niveum harboring more than 20 introns within a single rRNA primary transcript [3].

Notably, group I introns are absent from bilateral metazoans, with rare exceptions in a few non-bilateral basal lineages and five shark species [2]. This patchy distribution reflects a complex evolutionary history involving both vertical inheritance and extensive horizontal transfer [4] [6].

Table 2: Distribution of Group I Introns Across Biological Kingdoms

| Organism Group | Common Genomic Locations | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria & Bacteriophages | rRNA, tRNA, phage protein-coding genes | Sporadic but widespread |

| Fungi | Nuclear rDNA, mitochondrial genes | Very common in some lineages |

| Algae & Plants | Chloroplast & mitochondrial genomes | Frequent in organelles |

| Myxomycetes | Nuclear ribosomal DNA | Exceptionally abundant |

| Metazoans | - | Largely absent |

Mobility Mechanisms and Evolutionary Trajectories

Group I introns employ sophisticated mobility mechanisms that enable their spread within and between genomes. Approximately one-fourth to one-third of group I introns contain open reading frames (ORFs) that encode homing endonucleases (HEs) [2]. These highly specific DNA endonucleases initiate a process called "homing" by recognizing and cleaving intronless cognate alleles at specific target sequences [4] [5]. The subsequent DNA repair process using the intron-containing allele as a template results in the conversion of the intronless allele to an intron-containing one, enabling super-Mendelian inheritance of the intron [2].

The evolutionary lifecycle of group I introns and their associated HEs follows a cyclical pattern known as the "homing cycle" [2]. Once an intron becomes fixed in a population through homing, selective pressure to maintain a functional HE diminishes, leading to its degeneration through genetic drift. Eventually, the intron itself may be lost from the population, allowing empty alleles to re-emerge and potentially be invaded again, completing the cycle [2]. Some HEs escape this degenerative fate by acquiring maturase activity, wherein they assist in the folding and splicing of their host intron [2] [4]. This bifunctionality creates a selective advantage for maintaining the HE, as it becomes essential for proper gene expression of the host organism.

An alternative mobility pathway, particularly for introns lacking HEs, is reverse splicing [6]. In this RNA-mediated process, a free intron RNA can reinsert itself into a homologous or heterologous RNA transcript through the reverse of the splicing reaction. Subsequent reverse transcription and recombination can then genomic the insertion. Reverse splicing may explain the long-distance movement of group I introns to non-homologous sites and their spread between evolutionarily distant taxa [6].

Application Notes for Biocomputing Research

Engineering Trans-Splicing Ribozymes

The conversion of natural cis-splicing group I introns into trans-splicing configurations provides a powerful platform for programming RNA-based computational operations in biological systems [7] [3]. In trans-splicing ribozymes, the 5' exon is removed, and the ribozyme's 5' terminus is redesigned to base-pair with a complementary target site on a separate substrate RNA molecule. Upon binding, the ribozyme catalyzes a splicing reaction that replaces the 3' portion of the substrate RNA with the 3' exon carried by the ribozyme [7].

This precise RNA reprogramming capability can be harnessed for multiple biocomputing applications:

- Logic Gate Implementation: Engineered ribozymes can function as Boolean logic gates by designing their activity to be conditional on the presence of specific input RNAs (e.g., AND, OR, NOT gates) [3].

- Signal Amplification Cascades: The catalytic nature of ribozymes enables them to process multiple substrate molecules, allowing for the construction of signal amplification pathways within synthetic genetic circuits.

- State Memory Devices: Trans-splicing events that create stable, heritable changes in RNA or subsequent protein expression can serve as biological memory elements in cellular computing systems.

Comparative Analysis of Model Ribozyme Systems

The selection of appropriate group I intron scaffolds is critical for optimizing the performance of engineered ribozymes in biocomputing applications. Two particularly well-characterized systems offer complementary advantages:

Tetrahymena thermophila Ribozyme (Subgroup IC1): This 414-nucleotide ribozyme represents the historical prototype for group I intron studies [7] [3]. Its extensive characterization provides a rich knowledge base for engineering, though its relatively large size and complex folding pathway may present challenges for some applications [7].

Azoarcus Bacterial Ribozyme (Subgroup IC3): At only 205 nucleotides, the Azoarcus ribozyme is approximately half the size of the Tetrahymena ribozyme and exhibits significantly faster folding kinetics in vitro [7]. Its compact architecture and efficient catalysis make it an attractive candidate for engineering minimal computing elements, though its trans-splicing efficiency in cellular environments requires further optimization [7].

Table 3: Comparison of Model Group I Introns for Biocomputing Applications

| Characteristic | Tetrahymena thermophila | Azoarcus sp. |

|---|---|---|

| Subgroup Classification | IC1 | IC3 |

| Length | ~414 nucleotides | ~205 nucleotides |

| Natural Origin | Nuclear LSU rRNA gene | Bacterial tRNA-Ile gene |

| Folding Kinetics | Slter, more complex | Faster, more efficient |

| Structural Characterization | Extensive | High-resolution crystal structures |

| Trans-Splicing Efficiency | Moderate in cells | High in vitro, lower in cells |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Trans-Splicing Assay

This protocol describes a standardized method for assessing the activity of engineered group I intron ribozymes in trans-splicing reactions under near-physiological conditions in vitro [7].

Materials and Reagents

- Purified Ribozyme RNA: In vitro transcribed and gel-purified

- Substrate RNA: Containing target sequence for ribozyme recognition

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5-10 mM MgCl₂

- NTPs: 1 mM GTP (initiates splicing), 0.5 mM ATP, CTP, UTP

- Stop Solution: 90% formamide, 50 mM EDTA

- Polyacrylamide Gel Equipment: For denaturing urea-PAGE analysis

Procedure

- Ribozyme Annealing: Denature the ribozyme RNA (1-5 µM) at 95°C for 1 minute in reaction buffer without MgCl₂, then cool slowly to 37°C over 15 minutes to promote proper folding.

- Reaction Initiation: Add MgCl₂ to a final concentration of 5-10 mM along with substrate RNA (1-5 µM) and GTP (1 mM). Mix thoroughly and incubate at 37°C.

- Timepoint Sampling: Remove aliquots at predetermined timepoints (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes) and mix immediately with stop solution to quench the reaction.

- Product Analysis: Resolve the reaction products by denaturing urea-PAGE (6-10% acrylamide). Visualize RNA bands using ethidium bromide, SYBR Gold, or radioisotopic labeling.

- Quantification: Determine the percentage of spliced product relative to total substrate using densitometry or phosphorimaging analysis.

Optimization Notes

- The Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) design should be optimized for each ribozyme-substrate pair. For Azoarcus ribozymes, designs that mimic the natural anticodon stem-loop context of the native tRNA environment often yield superior activity [7].

- Magnesium concentration (typically 5-10 mM) and temperature (37-45°C) should be systematically optimized for each engineered ribozyme.

- For kinetic analysis, multiple substrate concentrations should be tested to determine Michaelis-Menten parameters (Kₘ and kcat).

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Assessing Trans-Splicing Ribozyme Activity In Vitro.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Group I Intron and Biocomputing Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Transcription Kits | T7/SP6 RNA polymerase-based systems | Production of catalytic RNA components |

| RNA Purification Materials | Denaturing PAGE systems or FPLC | Isolation of highly active ribozyme RNA |

| Magnesium Salts | High-purity MgCl₂ (5-10 mM range) | Essential cofactor for ribozyme folding and catalysis |

| Guanosine Nucleotides | GTP, GMP, or GDP (1 mM typical) | Initiates splicing as exogenous nucleophile |

| Extended Guide Sequences | Custom-designed oligonucleotides (4-20 nt) | Enhances target recognition and binding specificity |

| Fluorescent Reporters | FRET pairs (e.g., Cy3/Cy5) or GFP variants | Real-time monitoring of splicing activity in vitro and in vivo |

| Homing Endonucleases | LAGLIDADG or GIY-YIG family proteins | DNA-level programming of genetic circuits |

Future Perspectives in Biocomputing

The unique catalytic properties of group I introns position them as versatile components for next-generation biocomputing systems. Future research directions should focus on enhancing the predictability and orthogonality of engineered ribozymes to enable the construction of more complex computational networks in cellular environments. Key challenges include improving the in vivo stability and kinetics of compact ribozymes like the Azoarcus system, developing allosteric control mechanisms that regulate ribozyme activity in response to specific molecular inputs, and creating computational models that accurately predict ribozyme-substrate interactions in the context of cellular RNA folding landscapes [7] [3].

The integration of group I intron-based RNA computation with other synthetic biology components—such as CRISPR systems, protein-based logic gates, and cell-free expression platforms—will enable the development of sophisticated hybrid computational devices capable of processing complex biological information for therapeutic, diagnostic, and environmental applications. As our understanding of RNA structure-function relationships deepens, the programmability of group I intron ribozymes will continue to expand, solidifying their role as fundamental components in the emerging toolkit of biological computing.

The two-step transesterification splicing pathway is the fundamental chemical mechanism used by group I intron ribozymes to self-excise from RNA transcripts and ligate the flanking exons. This process is catalyzed entirely by the catalytic RNA core of the intron, without the requirement for protein enzymes, making it a cornerstone mechanism for biocomputing research and synthetic biology applications. The pathway relies on consecutive phosphoester transfers that rearrange the RNA backbone, resulting in precise splicing outcomes. Understanding this core mechanism enables researchers to engineer trans-splicing group I introns for diverse applications including RNA repair, therapeutic development, and molecular programming [3] [8].

For synthetic biologists and drug development professionals, this self-splicing mechanism offers a programmable RNA processing system with predictable kinetics and modular components. The ribozyme's ability to function in trans—splicing together exons from separate RNA molecules—enables innovative approaches for rewiring genetic circuits and developing RNA-based therapeutics. Recent advances have demonstrated the clinical potential of this technology, with FDA-approved Phase I/IIa IND trials for trans-splicing ribozymes in cancer treatment [8].

Detailed Mechanism of Two-Step Transesterification

Biochemical Pathway

The two-step transesterification mechanism proceeds through defined sequential reactions that require specific cofactors and produce characteristic intermediate structures:

Step 1: 5' Splice Site Cleavage - The reaction is initiated when the 3' hydroxyl group (3'OH) of an exogenous guanosine cofactor (exoG, typically GTP) performs a nucleophilic attack on the phosphodiester bond at the 5' splice site. This transesterification reaction results in cleavage at the 5' splice site and covalent attachment of the guanosine to the 5' end of the intron RNA. The upstream exon is released with a free 3'OH group, while the guanosine cofactor becomes attached to the intron's 5' terminus [3] [9].

Step 2: 3' Splice Site Cleavage and Exon Ligation - The 3'OH group of the released 5' exon now acts as a nucleophile, attacking the phosphodiester bond at the 3' splice site. This second transesterification results in ligation of the flanking exons and release of the intron RNA. The intron is excised as a linear molecule containing the initially added guanosine at its 5' end [3] [10].

Table 1: Key Components of the Transesterification Reaction

| Component | Role in Mechanism | Chemical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Guanosine (exoG) | Nucleophile initiator | Provides free 3'OH for first nucleophilic attack |

| 5' Splice Site | First reaction site | Phosphate bond attacked by exoG 3'OH |

| 3' Splice Site | Second reaction site | Phosphate bond attacked by exon 3'OH |

| ωG (Omega G) | Terminal intron nucleotide | Participates in guanosine binding site in catalytic core |

| Catalytic RNA Core | Reaction catalyst | Precisely positions substrates for transesterification |

Structural Requirements

The group I intron ribozyme folds into a conserved tertiary structure with specific domains essential for catalysis. The catalytic core consists of paired RNA segments (P3-P9) organized into three structural domains: the substrate domain (P1-P2), scaffold domain (P4-P6), and catalytic domain (P3-P7). The P7 helix contains the guanosine binding site (G site) where the exogenous guanosine cofactor initially binds before the first transesterification step. The internal guide sequence within P1 facilitates specific recognition of the 5' splice site through base-pairing interactions [3].

The reaction requires magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) in the catalytic core, which serve to stabilize the transition state and facilitate the transesterification chemistry. The same catalytic mechanism involving two magnesium ions is employed by the spliceosome, suggesting an evolutionary relationship between self-splicing ribozymes and the eukaryotic splicing machinery [10] [3].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

In Vitro Splicing Assay Protocol

Objective: To demonstrate and analyze group I intron self-splicing via the two-step transesterification pathway in vitro.

Materials:

- DNA template encoding the group I intron flanked by exons

- T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase for in vitro transcription

- Nucleotide triphosphates (NTPs)

- Guanosine triphosphate (GTP)

- Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂)

- Buffer components (Tris-HCl, pH 7.5)

- Stop solution (EDTA, formamide)

- Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis equipment

Method:

- Template Preparation: Linearize plasmid DNA containing the group I intron construct or prepare by PCR amplification. For the CIRC method, ensure the construct contains an intact group I intron [9].

In Vitro Transcription: Synthesize the precursor RNA using T7 RNA polymerase in a reaction containing:

- 1 μg DNA template

- 2 mM each NTP

- 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- 10 mM MgCl₂

- 5 mM DTT

- 2 mM spermidine

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours [9]

Splicing Reaction: Set up the splicing reaction with:

- Precursor RNA (0.1-1.0 μM)

- 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- 10-100 mM MgCl₂ (concentration affects efficiency)

- 1 mM GTP

- Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [9]

Reaction Termination: Add EDTA to 25 mM final concentration to chelate Mg²⁺ and stop the reaction.

Product Analysis:

- Separate RNA products by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8% PAGE, 7M urea)

- Visualize using ethidium bromide, SYBR Gold, or autoradiography if using radiolabeled RNA

- Identify bands corresponding to precursor RNA, spliced exons, and excised intron

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For introns with non-G 5' termini, additional 5' G residues may be needed for efficient T7 transcription without affecting circularization efficiency [9].

- Mg²⁺ concentration optimization is critical—test range from 10-100 mM

- Time course experiments (0-120 minutes) can reveal splicing kinetics

Trans-Splicing Applications for RNA Repair

The two-step transesterification mechanism can be harnessed for therapeutic RNA repair using engineered group I intron ribozymes that operate in trans. This approach enables correction of disease-causing mutations at the RNA level:

Protocol for Targeted RNA Repair:

Ribozyme Design:

- Engineer the Tetrahymena thermophila group I intron to recognize a specific target mRNA

- Modify the Internal Guide Sequence (IGS) to base-pair with the target RNA upstream of the mutation site

- Include the correct sequence in the ribozyme's 3' exon to replace the mutated region [8]

Splice Site Identification:

- Computationally predict accessible uridine residues in the target RNA using free energy calculations (IntaRNA2 software)

- Select splice sites with favorable binding energies (ΔG) for ribozyme recognition [8]

Efficiency Optimization:

- Incorporate an Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) with 3 nucleotides forming a P1 extension (P1ex)

- Include an antisense duplex (8-46 bp) for enhanced target binding

- Test EGS libraries with randomized internal loops to identify high-efficiency variants [8]

Validation in Cellular Models:

- Transfert engineered ribozyme into target cells (e.g., HEK293 NF1-/- for neurofibromatosis type I model)

- Analyze trans-splicing products by RT-PCR and sequencing

- Confirm functional protein expression via Western blot or functional assays [8]

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Splicing Methods

| Method | Splicing Efficiency | Mg²⁺ Requirement | Incubation Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIRC (Complete Intron) | High | Low (mild conditions) | Short | Large RNA circularization (>12 kb) |

| PIE (Permuted Intron-Exon) | Moderate | High (high Mg²⁺) | Extended | Standard circRNA production |

| PIET (Trans-Splicing) | Moderate to High | Adjustable | Controlled by component addition | Regulated splicing applications |

| Therapeutic Trans-Splicing | Variable (enhanceable with EGS) | Physiological | Dependent on delivery | NF1, cancer, genetic disorders |

Visualization of Splicing Pathways

Two-Step Transesterification Mechanism

RNA Circularization Methods Comparison

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Trans-Splicing Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Protocol Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I Intron Sources | Tetrahymena thermophila, Anabaena (Ana) | Catalytic RNA core for splicing | CIRC method uses intact forms [9] |

| RNA Purification Tools | RNase R, Oligo(dT) beads | Circular RNA purification | RNase R degrades linear RNAs only [9] |

| Splicing Cofactors | GTP (Guanosine Triphosphate) | Initiates first transesterification | Not required for CIRC method [9] |

| Magnesium Salts | MgCl₂ | Catalytic ion for ribozyme function | Concentration affects efficiency [9] |

| Target RNA Templates | NF1 mRNA, Dystrophin mRNA | Therapeutic splicing targets | Full-length dystrophin (~12 kb) demonstrated [9] [8] |

| Computational Tools | IntaRNA2 software | Splice site prediction | Calculates binding free energies [8] |

| Delivery Systems | Transfection reagents, Viral vectors | Cellular ribozyme delivery | Critical for therapeutic applications [8] |

| Detection Methods | RT-PCR, RNase R assay | Splicing product validation | Confirms precise exon ligation [9] |

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Enhancing Splicing Efficiency

Multiple strategies can optimize the efficiency of the two-step transesterification pathway for research and therapeutic applications:

Extended Guide Sequences (EGS): Incorporating EGS elements with optimal internal loop configurations can enhance trans-splicing efficiency by over 50-fold. Combinatorial libraries with randomized EGS sequences can identify high-performance variants through barcode selection [8].

Magnesium Optimization: The CIRC method demonstrates enhanced RNA circularization efficiency under mild conditions (lower Mg²⁺ concentrations), preserving RNA integrity while maintaining high splicing yields. Titrate Mg²⁺ between 10-100 mM for optimal results in specific applications [9].

Sequence Engineering: For the CIRC method, removing homology arms required in traditional PIE approaches significantly enhances circularization efficiency. Additionally, 5' terminal G residues can be added to facilitate T7 transcription without compromising circularization efficiency [9].

Applications in Biocomputing

The predictable nature of the two-step transesterification mechanism enables its use in synthetic biology and molecular programming:

Logic Gate Construction: Engineered ribozymes can function as programmable RNA processors, executing Boolean operations through controlled splicing events.

Molecular Sensors: Splicing-based biosensors can detect specific RNA sequences through IGS complementarity, triggering detectable output signals via trans-splicing.

RNA Circuitry: Multiple ribozymes can be networked to create complex computational RNA devices that process genetic information and execute programmed responses.

The continued refinement of group I intron trans-splicing technology, particularly through methods like CIRC that offer improved efficiency and simplified implementation, positions this mechanism as a powerful tool for both therapeutic development and biocomputing research.

Group I introns are catalytic RNAs (ribozymes) that excise themselves from primary RNA transcripts and ligate the flanking exons via two transesterification reactions [7]. These natural cis-splicing ribozymes can be engineered into trans-splicing variants capable of modifying separate substrate RNAs, making them powerful tools for biocomputing research and potential therapeutic applications, such as repairing mutated mRNAs [7]. The structural diversity of group I introns is classified into several major subgroups (IA, IB, IC, ID, IE, etc.), which exhibit distinct structural features and biochemical properties [11]. Understanding this classification is paramount for selecting the appropriate ribozyme for specific biocomputing tasks, as characteristics like size, folding kinetics, and optimal splice site recognition vary between subgroups [7] [11]. For instance, the well-characterized Tetrahymena thermophila ribozyme (subgroup IC1) and the smaller, fast-folding Azoarcus ribozyme (subgroup IC3) serve as contrasting models for developing synthetic genetic circuits and RNA-based sensors [7].

Classification and Characteristics of Major Subgroups

The classification of group I introns into subgroups is based on conserved primary sequences and secondary structure features. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of several major subgroups, highlighting their diverse origins and properties relevant to biocomputing applications.

Table 1: Classification and Key Features of Major Group I Intron Subgroups

| Subgroup | Representative Intron | Structural Features | Size (Nucleotides) | Trans-Splicing Efficiency & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC1 | Tetrahymena thermophila (16S rRNA) | Well-characterized conserved core structure [7]. | ~400 [7] | High efficiency in vitro; widely used as a model system; requires optimized EGS for high trans-splicing activity [7]. |

| IC3 | Azoarcus sp. (tRNAIle) | Compact, highly structured core; fast-folding kinetics [7]. | 205 [7] | Efficient in vitro with a design mimicking its natural cis-splicing context; lower efficiency in E. coli cells compared to IC1 [7]. |

| IE | Didymium iridis | Distinct structural adaptations in the catalytic core. | Information Missing | Capable of trans-splicing; efficiency can be improved with an Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) [7]. |

| I (General) | Twort intron (used in structural studies) | Conserved tertiary structure with P4-P6 and P3-P9 domains [11]. | Information Missing | Binds fungal mtTyrRSs (e.g., CYT-18) via a conserved phosphodiester-backbone recognition mechanism [11]. |

The structural divergence between subgroups is primarily localized to specific regions, such as the group I intron binding surface recognized by protein cofactors. Fungal mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases (mtTyrRSs), like the CYT-18 protein from Neurospora crassa, have evolved a specialized binding surface to stabilize the catalytically active RNA structure of group I introns [11]. This surface includes an N-terminal extension (H0) and small insertions (Ins 1, Ins 2), which show significant variation across different Pezizomycotina fungi (e.g., A. nidulans and C. posadasii), contributing to intron-binding specificity [11].

Experimental Protocols for Trans-Splicing Analysis

In Vitro Trans-Splicing Assay for Splice Site Identification

This protocol identifies accessible splice sites (uridine residues) on a target mRNA for a given trans-splicing ribozyme, adapted from studies on the Azoarcus and Tetrahymena ribozymes [7].

- Principle: A pool of ribozymes with a randomized substrate recognition sequence is used. Following the reaction, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) specifically amplifies the trans-splicing products, which are then sequenced to identify the utilized splice sites [7].

- Materials:

- Purified Ribozyme Pool: T7-transcribed ribozyme with a randomized 9-12 nucleotide Internal Guide Sequence (IGS) at its 5' end.

- Target Substrate RNA: In vitro transcribed model mRNA (e.g., Chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) mRNA).

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5-10 mM MgCl₂.

- Guanosine Nucleotide: 1 mM GTP or G, to initiate the splicing reaction.

- RT-PCR Kit: Enzymes and reagents for reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction.

- Procedure:

- Incubation: Mix 1 pmol of the ribozyme pool with 0.5 pmol of the target substrate RNA in reaction buffer. Add 1 mM GTP to initiate the reaction.

- Incubation Conditions: Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes under near-physiological conditions to mimic the cellular environment.

- RNA Extraction: Post-incubation, purify the RNA products using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

- Reverse Transcription (RT): Use a gene-specific primer complementary to the ribozyme's 3' exon to transcribe the RNA products into cDNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the cDNA using primers specific to the 3' exon of the ribozyme and the 5' region of the target substrate.

- Product Analysis: Clone the PCR products and sequence individual clones, or use high-throughput sequencing to identify the sequence at the exon-exon junction, thereby revealing the splice site (U) used on the substrate mRNA.

Protocol for Assessing Trans-Splicing Efficiency with an EGS

This protocol measures the efficiency of a trans-splicing reaction, comparing designs with and without an Extended Guide Sequence (EGS), which provides additional base-pairing to the substrate [7].

- Principle: The ribozyme and substrate are incubated under defined conditions. The products are separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and the ratio of spliced product to unreacted substrate is quantified to determine efficiency [7].

- Materials:

- Radiolabeled Substrate RNA: Target RNA body-labeled with ³²P during in vitro transcription.

- Defined Ribozyme: Purified, unlabeled trans-splicing ribozyme, with or without an EGS.

- Stop Solution: 95% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Combine radiolabeled substrate with an excess of ribozyme (e.g., 5:1 molar ratio) in reaction buffer with MgCl₂ and GTP.

- Time-Course Sampling: Remove aliquots from the reaction mixture at specific time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min).

- Reaction Termination: Immediately mix each aliquot with the formamide-based stop solution and heat to 95°C for 2 minutes to denature the RNA and halt the reaction.

- Product Separation: Resolve the reaction products by denaturing PAGE (e.g., 8% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea).

- Visualization & Quantification: Expose the gel to a phosphorimager screen and quantify the bands corresponding to the substrate and the trans-spliced product using image analysis software (e.g., ImageQuant). The splicing efficiency is calculated as the percentage of substrate converted to product over time.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in the analysis of trans-splicing group I introns:

Research Reagent Solutions

Key reagents and their functions for experimental work with trans-splicing group I introns are summarized below.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Trans-Splicing Group I Intron Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in Trans-Splicing |

|---|---|

| T7 RNA Polymerase | In vitro transcription of ribozyme and substrate RNAs with high yield [7]. |

| ³²P-UTP (Radiolabeled) | Radioactive labeling of RNA for highly sensitive detection and quantification of splicing products via gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging [7]. |

| Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) | An elongation of the ribozyme's 5' terminus that provides additional base-pairing with the substrate RNA, increasing target specificity and splicing efficiency [7]. |

| CYT-18 Protein (mtTyrRS) | A fungal mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase that functions as a splicing cofactor by binding and stabilizing the catalytically active structure of group I introns [11]. |

| Cloning Vector (e.g., pUC19) | For the molecular cloning of PCR products from RT-PCR assays, enabling sequencing and identification of splice sites [7]. |

Group I introns are not merely self-splicing RNA elements; they are sophisticated mobile genetic entities whose propagation is engineered by highly specific homing endonucleases (HEs). These "selfish" enzymes facilitate the super-Mendelian inheritance of their host introns through a precise molecular mechanism known as homing [2] [12]. In the context of advancing biocomputing research, understanding and harnessing this mobility is paramount. Homing endonucleases function as molecular programmers, inserting genetic code with remarkable precision through a well-characterized double-strand break (DSB) and repair cycle [13] [14]. This application note details the mechanisms, key reagents, and experimental protocols for leveraging the homing cycle in sophisticated gene network design and therapeutic development, framing these natural systems as programmable tools for synthetic biology.

The Molecular Mechanism of the Homing Cycle

The homing cycle is a gene conversion process that enables the copying of a mobile genetic sequence (e.g., a group I intron) into a cognate allele that lacks it. The process is initiated and driven by the homing endonuclease.

The Core Homing Process

The homing cycle can be broken down into a series of discrete, programmable steps, as illustrated in the diagram below.

- Expression and Cleavage: In a heterologous cell containing one allele with the homing endonuclease gene (HEG+) and one without (HEG-), the HE is expressed. The enzyme then recognizes and introduces a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) in the cognate recognition site of the HEG- allele [13] [12].

- Repair and Gene Conversion: The cellular DNA repair machinery, specifically the homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, uses the homologous HEG+ allele as a template to repair the break. This process copies the HE gene and its associated intron into the previously empty allele, resulting in two HEG+ alleles [13] [14]. The long recognition sites of HEs (12-40 bp) ensure this process occurs with high specificity and minimal off-target effects, a critical feature for biocomputing applications requiring precise logic operations [13].

Distinguishing Features of Homing Endonucleases

Homing endonucleases are uniquely suited for programming gene conversion compared to conventional restriction enzymes. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Homing Endonucleases versus Type II Restriction Enzymes

| Feature | Homing Endonucleases | Type II Restriction Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Site | Long (12-40 bp), often asymmetric [13] [12] | Short (4-8 bp), usually palindromic [12] |

| Sequence Tolerance | Tolerant of some degeneracy [13] [12] | Highly specific; variations abolish activity [12] |

| Phylogenetic Distribution | All domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria, Eukarya) [2] [12] | Primarily Bacteria and Archaea [12] |

| Genomic Context | Introns, inteins, or freestanding [13] [12] | Almost always freestanding [12] |

| Primary Function | Self-propagation (homing) [12] | Host defense (restriction) [12] |

Major Families of Homing Endonucleases

Homing endonucleases are classified into distinct families based on conserved amino acid motifs and their structural folds. Understanding these families is essential for selecting the appropriate enzyme for a given application. The major families and their characteristics are detailed below.

Table 2: Major Structural Families of Homing Endonucleases

| Family | Conserved Motif(s) | Oligomeric State | Prototypical Member | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAGLIDADG | 1 or 2 LAGLIDADG motifs [13] [12] | Monomer or Homodimer [13] | I-CreI, I-DmoI [13] | Most common family; saddle-shaped structure interacting with DNA major groove [12] |

| GIY-YIG | GIY-YIG motif in N-terminal region [13] [12] | Monomer [13] | I-TevI [13] [12] | Modular structure with separable catalytic and DNA-binding domains [13] |

| HNH | H-N-H consensus sequence [13] [12] | Monomer [13] | I-HmuI [13] [12] | Contains a zinc finger domain; related to His-Cys box family [12] |

| His-Cys Box | ~30 aa region with 2 His, 3 Cys [13] [12] | Homodimer [13] | I-PpoI [13] [12] | Metal ion coordination for catalysis; possibly related to H-N-H family [13] [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Leveraging the homing cycle for research and development requires a specific set of molecular tools. The following table catalogs essential reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Homing Endonuclease Work

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Engineered HEs | Tailored endonucleases re-engineered from wild-type templates (e.g., LAGLIDADG) to recognize non-native DNA sequences for gene targeting [13]. | I-CreI and I-DmoI derivatives [13] |

| Group I Intron Database | A comprehensive, unified database providing group I intron sequences with precise exon-intron boundaries, subtype information, and putative HEs [15]. | https://github.com/LaraSellesVidal/Group1IntronDatabase [15] |

| Trans-splicing Ribozyme Scaffolds | Engineered group I introns (e.g., from Azoarcus or Tetrahymena) that can be repurposed to perform trans-splicing reactions for targeted RNA repair or reprogramming [7]. | Azoarcus ribozyme (IC3 subgroup) [7] |

| MARC1 Mouse Line | A transgenic mouse line containing multiple dormant homing guide RNA (hgRNA) barcoding elements for lineage tracing studies upon crossing with a Cas9-expressing line [16]. | MARC1 (PB3 and PB7 lines) [16] |

| Homing Site Reporters | Plasmid-based assays with an integrated HE recognition site upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP). Cleavage and repair via HDR using a donor template restores reporter function, quantifying HE activity. | Custom cloning required |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Homing Endonuclease Activity and SpecificityIn Vitro

This protocol outlines a method for assessing the cleavage efficiency and specificity of a purified homing endonuclease.

I. Materials

- Purified homing endonuclease (e.g., I-CreI or engineered variant)

- Target plasmid DNA (containing the cognate recognition site)

- Off-target control plasmid DNA (containing a closely related sequence)

- Reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl₂, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT)

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA staining dye (e.g., GelRed)

II. Methodology

- Reaction Setup: In a 0.5 mL tube, combine 500 ng of target plasmid DNA with 1 µL of purified HE in a total volume of 20 µL of reaction buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Controls: Set up parallel reactions with (a) no enzyme (negative control) and (b) off-target control plasmid DNA.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding 2 µL of 10x DNA loading dye or by heat-inactivating the enzyme (e.g., 65°C for 15 min).

- Analysis: Load the entire reaction onto a 1% agarose gel. Run the gel at 100V for 45 minutes, visualize under UV light, and document.

III. Data Interpretation

- High Specificity: Complete cleavage of the target plasmid (evidenced by a shift from supercoiled to linear form) with no observable cleavage of the off-target plasmid.

- Low Specificity/Tolerance: Cleavage of both target and off-target plasmids, indicating tolerance for sequence degeneracy, which may require protein re-engineering for therapeutic applications [13].

Protocol 2: Assessing Gene Correction via Homing in Mammalian Cells

This protocol describes a cell-based assay to measure the efficiency of homing endonuclease-mediated gene correction.

I. Materials

- Mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293)

- Expression plasmid for the homing endonuclease

- "Homing Reporter" plasmid: A construct where the HE recognition site is inserted into a defective GFP gene, disrupting its coding sequence.

- "Donor Template" plasmid: Contains the functional HE gene (or another corrective sequence) flanked by homology arms matching the region around the break.

- Transfection reagent

- Flow cytometer

II. Methodology

- Cell Seeding: Seed 2 x 10^5 cells per well in a 12-well plate 24 hours before transfection.

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with a 1:1:1 molar ratio of the HE expression plasmid, Homing Reporter plasmid, and Donor Template plasmid.

- Control Transfections: Include controls lacking the HE expression plasmid or the Donor Template.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 48-72 hours to allow for expression, cleavage, and repair.

- Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze by flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of GFP-positive cells, indicating successful homing and gene correction.

III. Data Interpretation

- The percentage of GFP-positive cells in the complete reaction, minus the background from controls, quantifies the homing efficiency.

- This assay validates the enzyme's functionality in a cellular context and its potential for ex vivo gene therapy of monogenic diseases [13].

The experimental workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Applications in Biocomputing and Therapeutic Development

The unique properties of the homing system make it a powerful platform for advanced biological programming.

Ex Vivo Gene Therapy for Monogenic Diseases: Custom-designed HEs can correct defective genes with high specificity and low toxicity. The process involves extracting patient cells, correcting the gene defect ex vivo using HE-mediated HDR, and re-infusing the modified cells [13]. This approach is particularly suited for diseases amenable to stem cell or lymphocyte therapy.

Developmental Lineage Barcoding: The MARC1 mouse system utilizes "homing guide RNAs" (hgRNAs). When crossed with a Cas9-expressing line, these hgRNAs self-target and accumulate diverse, heritable mutations during cell divisions. The combinatorial mutation patterns serve as lineage barcodes, enabling the reconstruction of entire cellular lineage trees [16]. This provides a powerful tool for understanding development, cancer, and regeneration.

RNA Reprogramming with Trans-Splicing Ribozymes: Engineered group I introns can be used for trans-splicing to repair or reprogram target mRNAs. This dual-function modality simultaneously reduces disease-associated gene expression and induces therapeutic gene activity specifically in target cells [17]. A hTERT-targeting ribozyme has progressed to clinical trials for cancer treatment [17].

Logic Gate Operations in Synthetic Gene Circuits: The high specificity of HE-DNA recognition allows for the design of complex logic operations. For example, a synthetic circuit could be designed where a specific output gene is activated only upon the simultaneous correction of two different genomic loci by two distinct HEs, effectively creating a genetically encoded AND gate. This leverages the homing cycle's programmability for sophisticated biocomputing.

Trans-splicing represents a fundamental RNA processing mechanism in which exons from two separate pre-mRNA molecules are joined to form a single chimeric RNA transcript. This process stands in contrast to conventional cis-splicing, where exons within the same pre-mRNA molecule are connected [18]. Initially discovered in trypanosomes during RNA processing for variant surface glycoprotein, trans-splicing has since been documented across diverse eukaryotic lineages, from lower eukaryotes to vertebrates [18] [19]. The evolutionary trajectory of trans-splicing reveals dynamic changes across species, with this mechanism potentially originating from early eukaryotic ancestors and persisting as a functionally significant process despite variations in frequency and biological role across divergent lineages [18].

The molecular machinery facilitating trans-splicing shares remarkable conservation with canonical spliceosomal components. Evidence indicates that trans-splicing utilizes similar splicing signals and factors as alternative splicing, including snRNAs U2, U4, U5, and U6 [18]. In spliced-leader (SL) trans-splicing—a specialized form widespread in lower eukaryotes—a short noncoding exon from SL RNA is joined to the 5′-end of multiple pre-mRNAs, providing a mechanism for mRNA maturation and regulation that offers evolutionary advantages, particularly in processing polycistronic transcription units [18]. The conservation of splicing machinery across trans-splicing and cis-splicing mechanisms suggests an ancient evolutionary origin, with SL RNA potentially deriving from splicing U snRNAs in lower organisms with ancestral cis-splicing mechanisms [18].

Evolutionary Distribution and Quantitative Analysis of Trans-Splicing

The prevalence of trans-splicing exhibits remarkable variation across the eukaryotic domain, with certain lineages displaying extensive utilization while others employ it more sparingly. Comprehensive analysis of orthologous genes from completely sequenced eukaryotic genomes has revealed numerous shared features, suggesting that many RNA processing mechanisms have persisted since the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) [20]. Phylogenomic reconstructions indicate that both major U2 and minor U12 spliceosomes were already present in LECA, resulting from ancient duplication events [20].

Table 1: Comparative Frequency of Trans-Splicing Across Eukaryotic Lineages

| Organism/Lineage | Trans-Splicing Frequency | Primary Type | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma brucei | ~100% of genes | SL | Essential for processing polycistronic transcripts |

| Amphidinium carterae | ~100% of genes | SL | Dinoflagellate model |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | ~70% of genes | SL | Involved in growth recovery |

| Ascaris sp. | ~90% of genes | SL | Parasitic nematode |

| Adineta ricciae | ~60% of genes | SL | Rotifer species |

| Insects | ~1.58% of total genes | Inter/Intragenic | 1,627 events involving 2,199 genes |

| Vertebrates | Dramatically declined | Inter/Intragenic | Rare but physiologically significant |

The evolutionary distribution of trans-splicing demonstrates a fascinating pattern, with frequency peaking in protozoa, radiates, and protostomes before undergoing a dramatic decline in vertebrates [18]. The high percentage observed in invertebrates predominantly represents SL-type splicing, which can occur in 100% of genes in certain protists like A. carterae and K. micrum [18]. This distribution suggests that trans-splicing has experienced dynamic changes throughout eukaryotic evolution, with varying selective pressures and functional requirements shaping its utilization across lineages.

Recent genomic analyses continue to uncover new instances of trans-splicing in diverse organisms. In tunicates of the Ciona genus, which represent the closest invertebrate relatives to humans, approximately 50% of genes undergo SL trans-splicing, where a 16-nt 5′ exon of a 46-nt SL RNA joins to the trans-splice acceptor site of pre-mRNA [21]. The 5′ region upstream of the trans-splice acceptor site, termed the "outron," is discarded during this process [21]. Functional studies indicate that trans-spliced chimeric RNAs in C. elegans demonstrate higher translational efficiency than non-trans-spliced RNAs transcribed from the same gene, suggesting a potential regulatory advantage to this mechanism [21].

Molecular Mechanisms and Classification of Trans-Splicing

Fundamental Splicing Mechanisms

Trans-splicing events are broadly categorized based on the genomic origin of the participating RNA molecules. Intragenic trans-splicing occurs when pre-RNAs are transcribed from the same genomic locus, potentially producing chimeric RNAs through exon repetition, sense-antisense fusion, or exon scrambling [18]. Notable examples include the mod(mdg4) and lola genes in Drosophila, where intragenic trans-splicing generates diverse transcript isoforms [18]. Conversely, intergenic trans-splicing joins exons from separate genes, potentially located on different chromosomes, as observed in the human JAZF1-JJAZ1 chimeric RNA formed from genes on chromosomes 7 and 17 [18].

The molecular mechanism of SL trans-splicing involves precise recognition signals and splice site selection. Research in Ciona has revealed that trans-splice acceptor sites are preferentially located at the first functional acceptor site, with paired donor sites typically exhibiting weaker splicing signals [21]. Additionally, genes undergoing trans-splicing in Ciona display GU- and AU-rich 5′ transcribed regions, suggesting these sequence features may facilitate the trans-splicing mechanism [21].

Self-Splicing Group I Introns

Beyond spliceosomal trans-splicing, group I self-splicing introns represent another evolutionarily significant mechanism. These catalytic RNAs, ranging from 250-500 nucleotides, catalyze their own excision from precursor RNA without requiring spliceosomal proteins [2]. The self-splicing process occurs via two consecutive transesterification reactions initiated when an exogenous guanosine (ExoG) binds to the folded catalytic core of the ribozyme [2].

Group I introns are distributed across all domains of life, though they are notably abundant in fungi, plants, red algae, and green algae, which collectively account for approximately 90% of identified group I introns [2]. These autocatalytic elements are classified into five main groups (IA, IB, IC, ID, IE) based on conserved core domains and structural features, with further subdivision into 17 subgroups [2]. Although many group I introns self-splice efficiently in vitro, some require protein assistants with maturase functions for efficient splicing in vivo, which may be encoded by the intron itself or by host genome elements [2].

Experimental Protocols for Trans-Splicing Analysis

Transcriptome Assembly for Trans-Splicing Detection

Purpose: To comprehensively identify trans-splicing events and characterize 5′ transcribed regions (outrons) upstream of trans-splice acceptor sites.

Methodology:

- RNA-seq Library Preparation: Isolate high-quality RNA from target tissues or cell lines. For Ciona studies, 82 RNA-seq samples were utilized to ensure comprehensive coverage [21].

- Read Preprocessing: Use tools like cutadapt v1.11 to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from raw sequencing reads [21].

- Genome Alignment: Map preprocessed reads to the reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR v2.7.9a with appropriate parameter settings for the organism [21].

- Transcript Assembly: Reconstruct transcripts using assembly tools like StringTie v1.2.3 and Scallop v0.10.4 to identify novel transcripts with extended 5′ exons or novel exons upstream of known transcripts [21].

- Gene Locus Redefinition: Combine newly identified transcripts with annotated transcripts from existing models, maintaining the total gene count while expanding transcriptional diversity [21].

Validation: Confirm trans-splicing events through:

- Specific detection of SL sequences in RNA-seq reads

- Experimental validation using RT-PCR with junction-spanning primers

- Comparison with TSS-seq data that precisely identifies transcription start sites through oligo-capping methods [21]

Identification of Trans-Splice Acceptor Sites

Purpose: To precisely map trans-splice acceptor sites and distinguish them from conventional transcription start sites.

Methodology:

- TSS-seq Data Generation: Employ oligo-capping methods to specifically replace the 5′ cap structure of mRNA with a synthetic oligoribonucleotide, enabling precise identification of mRNA 5′ ends [21].

- Read Classification: Categorize TSS-seq reads into SL trans-spliced RNAs and non-trans-spliced RNAs based on the presence or absence of 5′ SL sequences [21].

- Genome Mapping: Map classified reads to the reference genome using STAR v2.7.9a to identify trans-splice acceptor sites and transcription start sites [21].

- Open Chromatin Validation: Integrate ATAC-seq data to identify open chromatin regions as supportive evidence of true TSSs, filtering out potential artifacts [21].

- Cluster Identification: Identify TSS clusters within regions around 5′ ends of transcripts or upstream of trans-splice acceptor sites, focusing on those overlapping with open chromatin regions [21].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform local enrichment analysis of nucleotide content using 30-bp sliding windows with statistical testing via Mann-Whitney U test and FDR correction [21]

- Conduct local motif enrichment analysis using binomial tests and Fisher's exact tests to identify sequences preferentially associated with trans-splicing [21]

- Predict motif binding sites using FIMO v5.0.1 to identify potential regulatory elements [21]

Research Reagent Solutions for Trans-Splicing Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Trans-Splicing Investigation

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Examples | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR v2.7.9a | Splice-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads | Mapping preprocessed reads to reference genomes | Critical for identifying junction-spanning reads |

| StringTie v1.2.3 | Transcript assembly from aligned RNA-seq reads | Reconstructing transcript models including novel isoforms | Effective for identifying extended 5′ exons |

| Scallop v0.10.4 | Alternative transcript assembler | Complementary assembly to StringTie | Improves comprehensive transcript identification |

| cutadapt v1.11 | Adapter trimming and read preprocessing | Quality control of RNA-seq data | Essential for preparing clean reads for alignment |

| FIMO v5.0.1 | Motif scanning and analysis | Identifying enriched sequence motifs in trans-spliced genes | Uses statistical models to evaluate motif significance |

| TSS-seq Methodology | Precise identification of transcription start sites | Genome-wide mapping of 5′ ends of mRNAs | Employs oligo-capping to label 5′ cap structures |

| ATAC-seq Data | Identification of open chromatin regions | Validating true transcription start sites | Helps filter out technical artifacts in TSS identification |

Implications for Biocomputing Research

The natural precedent of trans-splicing across divergent eukaryotes offers valuable insights and molecular tools for biocomputing applications. The modular nature of trans-splicing, particularly the programmable specificity of group I introns, provides a blueprint for designing synthetic RNA processing systems [2]. These natural systems demonstrate how precise sequence recognition can be harnessed to create programmable molecular circuits with predictable input-output relationships.

The mechanistic understanding of trans-splicing, especially the sequence requirements for splice site recognition and the structural features of catalytic introns, informs the development of synthetic biological components. For instance, the characteristic GU- and AU-rich 5′ transcribed regions associated with trans-splicing in Ciona provide design principles for engineering efficient synthetic trans-splicing systems [21]. Similarly, the preference for trans-splice acceptor sites at the first functional acceptor site, coupled with weak paired donor sites, offers strategic guidance for positioning synthetic trans-splicing elements [21].

Biocomputing applications can leverage these natural mechanisms to create sophisticated RNA-based computing platforms. The ability of group I introns to perform precise excision and ligation reactions without protein factors makes them ideal candidates for molecular logic gates and signal processing elements. Furthermore, the extensive characterization of trans-splicing across evolutionary diverse organisms provides a rich repository of components that can be adapted, modified, and recombined to create novel biocomputing systems with enhanced capabilities and predictable behaviors.

Engineering Biological Logic: Designing Trans-Splicing Ribozymes for Biocomputation and Therapy

The engineering of cis-acting ribozymes into trans-acting configurations represents a foundational principle in synthetic biology and therapeutic development. This conversion enables catalytic RNAs, which naturally act on themselves, to be reprogrammed to act on separate substrate RNAs. This principle is particularly powerful in the context of trans-splicing group I introns, which have recently gained significant attention with FDA-approved drugs entering Phase I/IIa IND trials for conditions like hepatocellular carcinoma and glioblastoma [8]. Within biocomputing research, this technology enables the construction of complex genetic circuits and programmable riboregulators, allowing for customizable, orthogonal, and predictable gene regulation [22]. This Application Note details the core engineering steps, quantitative design parameters, and experimental protocols for implementing this technology.

Core Engineering Principles and Key Design Parameters

The fundamental conversion from cis to trans involves re-engineering the ribozyme's structure to recognize an external target RNA instead of its own sequence. For the Tetrahymena thermophila group I intron, this primarily requires modifying two key recognition sequences [8].

Essential Sequence Modifications

- Internal Guide Sequence (IGS) Redesign: The native IGS, which specifies the splice site in cis, is converted into a short, trans-acting sequence. This new IGS is designed to be complementary to the target RNA, forming a duplex (the P1 helix) that positions the ribozyme's catalytic core at the correct uridylate (U) splice site on the substrate [8].

- Implementation of an Extended Guide Sequence (EGS): Trans-splicing efficiency can be dramatically increased by extending the ribozyme's 5'-terminus beyond the splice site. The EGS comprises [8]:

- A P1 extension (P1ex) of 3 nucleotides.

- An internal loop region.

- An antisense duplex of variable length (from 8 to over 40 base pairs) that enhances binding stability to the substrate.

The following table summarizes the key functional components and their design considerations.

Table 1: Core Components of a Trans-Splicing Group I Intron Ribozyme

| Component | Function | Design Consideration | Optimal Parameters / Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Guide Sequence (IGS) | Binds target RNA to define splice site via P1 helix [8]. | 6 nucleotides long; must base-pair with target sequence ending with a uridylate (U). | IGS is reverse complementary to target positions p-5 to p. |

| Splice Site Uridylate (U) | The nucleotide on the target RNA where splicing occurs [8]. | Computational prediction of accessibility is critical. | Identified via free energy calculations (e.g., using IntaRNA2) [8]. |

| Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) | Enhances splicing efficiency via increased binding stability [8]. | Includes P1ex, an internal loop, and an antisense duplex. | Antisense duplexes of 8-46 bp; EGS internal loop of 3-6 nt [8]. |

| 3'-Exon | The repair sequence or functional payload to be ligated to the target's 5'-fragment [8]. | Encodes the therapeutic gene correction or functional RNA output. | Wild-type cDNA sequence to correct a pathogenic mutation. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The engineering process involves balancing multiple quantitative parameters to optimize ribozyme activity. The data below, derived from recent studies, provides guidance for rational design.

Table 2: Quantitative Design Parameters for Trans-Splicing Ribozymes

| Parameter | Impact on Activity | Typical Range / Value | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Splice Site Accessibility (Free Energy) | Lower (more negative) binding free energy predicts higher splicing efficiency [8]. | Computed for all candidate Us in target region. | Method from [8]; uses IntaRNA2 with --seedBP 9 parameter. |

| Antisense Duplex Length | Longer duplexes increase binding affinity but may reduce product release or cellular availability. | 8 to 46 base pairs. | Shorter duplexes (8 bp) suffice with highly accessible splice sites [8]. |

| EGS Optimization Impact | A single beneficial mutation in the EGS can dramatically enhance efficiency. | >50-fold increase possible. | Combinatorial libraries with randomized EGS identified highly active variants [8]. |

| Mutational Tolerance (Neutral Network) | The number of functional ribozyme sequences is vast, allowing for extensive engineering. | >10^39 self-reproducing sequences estimated for group I introns [23]. | Generative models (DCA) produced active variants up to 65 mutations from wild-type [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Trans-Splicing Ribozyme

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a trans-splicing ribozyme to repair a mutated mRNA, based on the methodology used for NF1 mRNA repair [8].

Computational Splice Site Identification

Objective: To identify the most accessible uridylate (U) splice site on the target mRNA. Procedure:

- Input Sequence: Use the target mRNA coding sequence (e.g., human NF1, NM_001042492.3).

- Free Energy Calculation: For every uridylate downstream of a chosen start position (e.g., position 4500), compute the free energy of substrate binding using IntaRNA2 [8].

- Parameter Settings:

--seedBP 9--seedQRange 1-9--seedTRange (p-5)-(p+3)(for the specific U at positionp)- Use the

turner99energy parameters from the ViennaRNA package.

- Analysis: Calculate average binding energies across multiple sequence window sizes (100-600 nt). Select the site with the most favorable (most negative) average binding energy for experimental validation.

In Vitro Validation of Splice Site and EGS

Objective: To biochemically validate the computationally predicted splice site and identify a high-efficiency EGS. Reagents:

- DNA Template: Template for a truncated version of the target RNA.

- Ribozyme Library: A pool of ribozyme constructs with a randomized EGS region and a unique barcode in the 3'-tail for deep sequencing identification [8].

- NTPs: Including [α-32P]GTP for radioactive labeling or non-radioactive alternatives.

- Transcription Buffer: e.g., from MEGAscript T7 kit.

- Reaction Buffer: 10 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl₂.

Procedure:

- RNA Synthesis: In vitro transcribe and purify the target RNA and ribozyme library.

- Annealing: Mix 0.2-0.6 µM target RNA with a 2.5-fold molar excess of the ribozyme library in 10 mM Tris (without MgCl₂). Heat to 95°C for 2 min, then incubate at room temp for 5 min.

- Trans-splicing Reaction: Initiate the reaction by adding MgCl₂ to a final concentration of 10 mM. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Product Analysis: Resolve the reaction products via denaturing PAGE. Identify successful trans-splicing products by their altered size.

- EGS Selection: For the EGS library screen, extract the RNA post-reaction and use high-throughput sequencing of the ribozyme's barcode to identify EGS sequences enriched in the active fraction.

Cell-Based Validation

Objective: To confirm trans-splicing activity in a relevant cellular model. Cell Line: HEK293 NF1-/- cells stably expressing a full-length mutant mNf1 cDNA [8]. Procedure:

- Transfection: Transfer the validated ribozyme (with optimal EGS) into the cell line using a standard transfection method (e.g., lipofection).

- RNA Isolation: Harvest total RNA 24-48 hours post-transfection.

- RT-PCR Analysis: Perform reverse transcription followed by PCR with primers spanning the predicted splice junction.

- Validation: Sequence the PCR product to confirm the presence of the precise, corrected mRNA sequence.

Workflow and Biocomputing Application Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core engineering workflow and a key biocomputing application.

Engineering Workflow for Trans-Splicing Ribozymes

Trans-Splicing Ribozyme in Biocomputing Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Trans-Splicing Ribozyme Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrahymena thermophila Group I Intron Scaffold | The catalytic backbone for engineering trans-splicing ribozymes [8]. | Well-characterized sequence; used in FDA-approved drug trials [8]. |

| Computational Prediction Software | Identifies accessible splice sites on target mRNA. | IntaRNA2 with Turner '99 energy parameters [8]. |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit | Synthesizes target mRNA and ribozyme RNA for biochemical assays. | MEGAscript T7 Transcription Kit [24]. |

| Extended Guide Sequence (EGS) Library | A combinatorial pool of ribozymes with randomized EGS for efficiency optimization [8]. | Library includes a unique barcode in the 3'-tail for NGS identification. |

| Model Cell Line | Validates ribozyme function in a cellular context. | HEK293 NF1-/- cells expressing mutant mNf1 cDNA [8]. |

Synthetic biology aims to program living cells with customized functions, much like we program computers. A significant hurdle in this field has been scaling up the complexity of genetic circuits without being limited by the scarcity of reliable, non-interfering biological parts. The discovery and engineering of Split-Intron-Enabled Trans-splicing Riboregulators (SENTRs) mark a pivotal advancement in this endeavor [25] [26]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for utilizing SENTRs, a novel class of post-transcriptional regulators based on the programmable RNA trans-splicing activity of the group I intron ribozyme from Azoarcus [7]. SENTRs provide a versatile toolkit for constructing complex multi-input logic gates within bacterial cells, enabling sophisticated cellular computation for applications in biosensing and therapeutic intervention.

Background and Principles

The SENTR Mechanism

SENTRs are built upon the natural mechanism of group I intron ribozymes, which are catalytic RNAs that excise themselves from precursor RNA transcripts and ligate the flanking exons together. The SENTR system adapts the Azoarcus group I intron, a compact and fast-folding ribozyme, for trans-splicing applications [7]. The core innovation involves splitting the intron into two halves and fusing each half to de novo-designed External Guide Sequences (EGS) [25]. These EGSs are short RNA guides programmed to hybridize with specific target mRNAs via complementary base-pairing. This hybridization brings the split intron halves into proximity, allowing them to reassemble into a catalytically active ribozyme. The active ribozyme then performs a trans-splicing reaction, excising a portion of the target mRNA and replacing it with a new RNA sequence encoded by the SENTR's 3' exon [25] [26]. This mechanism allows for the reprogramming of gene expression at the mRNA level.

Key Features and Advantages

SENTRs exhibit several characteristics that make them ideal for building complex genetic circuits [25]:

- High Programmability: EGS sequences can be computationally designed to target virtually any mRNA.

- High Predictability: Machine learning models can predict trans-splicing activity from EGS sequences, enabling rational design.

- Low Leakage & Wide Dynamic Range: SENTRs exhibit minimal basal activity and strong activation upon target recognition.

- Orthogonality: Multiple SENTRs with distinct EGSs can function simultaneously in the same cell with minimal crosstalk, enabling parallel processing.

Application Notes: Implementing Logic Gates with SENTRs

SENTRs can be configured to perform a wide array of Boolean logic operations by sensing the presence or absence of specific input RNAs (e.g., mRNAs or synthetic small RNAs). The output is the production of a functional protein, such as a fluorescent reporter or a transcription factor, only when the logical condition is met.

Single-Layer Multi-Input Gates

A key advantage of SENTRs is their ability to process multiple inputs within a single regulatory layer. By coupling RNA trans-splicing with split intein-mediated protein trans-splicing, a single transcription factor can be controlled by multiple inputs [25]. For example, a six-input AND gate was constructed by inserting three orthogonal split introns and two orthogonal split inteins into a single gene (e.g., ecf20). Only when all six input RNAs are present do three sequential RNA splicing and two protein splicing reactions occur, producing a functional transcription activator that turns on a reporter gene [25]. This design dramatically reduces the need for multiple transcription factors required by conventional layered architectures.

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of SENTR-based logic gates as documented in the foundational research.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of SENTR-Based Systems

| Feature | Description / Performance Metric | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Wide dynamic range reported [25] | Enables strong distinction between "ON" and "OFF" states. |

| Predictability | High predictability enabled by machine learning models [25] | Facilitates forward design of functional EGS guides. |

| Orthogonality | Low crosstalk with multiple orthogonal SENTR pairs [25] | Allows for independent parallel operation of multiple gates. |

| Gate Complexity | Demonstration of up to six-input AND gates [25] | Represents the most complex genetic AND circuit reported. |

| Regulatory Scope | Regulation of fluorescent proteins, transcription factors, and sgRNAs [25] | A versatile tool for controlling diverse genetic outputs. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists the key biological parts and reagents required to implement SENTR-based genetic circuits.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SENTR Implementation

| Reagent / Component | Function in the System | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Azoarcus Group I Intron Fragments | The catalytic core of the SENTR system. | Split intron halves derived from the bacterial tRNAIle intron [7]. |

| External Guide Sequences (EGS) | Provides target specificity through RNA-RNA hybridization. | De novo-designed RNA sequences; design is facilitated by machine learning [25]. |

| Orthogonal SENTR Pairs | Enables independent logic channels within a single cell. | Libraries of SENTRs with low-sequence similarity EGSs to prevent crosstalk [25]. |

| Split Inteins | Enables post-translational reassembly of functional proteins. | Used in conjunction with split introns for multi-input protein-level gates (e.g., six-input AND) [25]. |

| Output Reporter Genes | Provides a measurable readout of circuit activity. | Fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP), transcription factors (e.g., ECF20), or sgRNAs [25]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing and Testing a Novel SENTR

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a new SENTR to target a specific mRNA of interest.

Workflow Diagram: SENTR Design and Testing

Materials:

- DNA Constructs: Plasmid backbone for SENTR expression in E. coli.

- Software: Computational tools for EGS design and machine learning models for activity prediction [25].

- Host Strain: E. coli cells suitable for genetic circuit expression.

- Reagents: Primers for cloning, culture media, and reagents for RT-PCR and sequencing.

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Select the target mRNA and the specific uridine (U) residue within it where trans-splicing should occur. The only sequence requirement is a U at the splice site to base-pair with a G in the ribozyme's Internal Guide Sequence (IGS) [7].

- EGS Design: Computationally design EGS sequences that are complementary to the regions flanking the target splice site. Use available machine learning models to predict and optimize the trans-splicing efficiency of the designed EGSs [25].

- Molecular Cloning: Synthesize the SENTR construct by fusing the designed EGSs to the 5' ends of the split Azoarcus intron halves. Clone this construct into an appropriate expression plasmid downstream of a constitutive or inducible promoter.

- Host Transformation: Transform the assembled plasmid into your E. coli laboratory strain.

- Functional Validation:

- Quantitative Output: Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence from a spliced reporter) and compare it to negative controls to assess dynamic range and leakage.

- Splicing Verification: Confirm the correct trans-splicing event using RT-PCR to amplify the spliced product, followed by sequencing of the amplicon.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Multi-Input AND Gate

This protocol describes the assembly of a logic gate requiring multiple inputs for activation, using the six-input AND gate as a paradigm [25].

Workflow Diagram: Six-Input AND Gate Construction

Materials:

- Orthogonal SENTR Pairs: A library of at least three SENTR pairs with EGSs designed to have minimal crosstalk [25].

- Split Intein Pairs: A library of orthogonal split inteins [25].

- Output Gene: The gene to be controlled (e.g., ecf20), split and modified with intron and intein fragments.

Procedure:

- Circuit Design: Select three orthogonal SENTR pairs and two orthogonal split intein pairs from existing libraries.