TdpABC: The DNA Sulfuration Defense System Protecting Thermophiles from Phage Invasion

This article explores the TdpABC system, a novel DNA phosphorothioate-based defense mechanism discovered in thermophilic bacteria and archaea.

TdpABC: The DNA Sulfuration Defense System Protecting Thermophiles from Phage Invasion

Abstract

This article explores the TdpABC system, a novel DNA phosphorothioate-based defense mechanism discovered in thermophilic bacteria and archaea. We detail its unique two-step 'activation-sulfur substitution' mechanism, wherein the TdpC enzyme adenylates the DNA backbone before incorporating a sulfur atom. The system provides immunity by enabling the TdpAB complex to selectively degrade PT-free invading phage DNA, while PT modifications on self-DNA prevent autoimmunity. Covering foundational biology, structural insights from cryo-EM, and its self/non-self discrimination capability, this analysis also positions TdpABC within the broader bacterial defensome and discusses its potential applications in biotechnology and understanding phage-host coevolution.

Unraveling TdpABC: The Discovery and Core Mechanism of a Novel DNA Modification Defense

The TdpABC system represents a recently discovered hypercompact DNA phosphorothioation-based anti-phage defense mechanism in extreme thermophiles. This technical guide details its novel two-step enzymatic mechanism via an adenylated DNA intermediate, its unique structural biology revealed by cryo-EM, and its sophisticated self/non-self discrimination system. We provide comprehensive quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools to support research and therapeutic development targeting this unique bacterial immune system.

Bacterial defense systems against bacteriophages have evolved remarkable molecular sophistication, with DNA modification representing a fundamental protective strategy. Among these, DNA phosphorothioate (PT) modification involves the enzymatic replacement of a non-bridging oxygen atom in the DNA sugar-phosphate backbone with sulfur [1]. This modification creates a structural signature that bacterial immune systems can recognize to distinguish self from non-self DNA.

The recently characterized TdpABC system expands this paradigm through its hypercompact organization and unique biochemical mechanism in extreme thermophiles. Unlike previously identified PT systems, TdpABC operates via a distinctive adenylated intermediate during the sulfur incorporation process [1]. This system provides a fascinating model for studying minimalist yet highly effective antiviral defense in organisms thriving under extreme environmental conditions, offering potential insights for both fundamental microbiology and applied biotechnology.

Molecular Mechanism of the TdpABC System

Core Components and Their Functions

The TdpABC system comprises three core components that orchestrate a coordinated defense mechanism against invasive phage DNA:

- TdpC: Catalyzes the DNA backbone modification through a two-step process involving initial ATP-dependent adenylation followed by sulfur atom incorporation [1]

- TdpA: Forms a hexameric complex that binds and encircles duplex DNA in a spiral staircase conformation via hydrogen bonding [1]

- TdpB: Functions as a dimeric nuclease that degrades PT-free phage DNA [1]

Two-Step Sulfur Incorporation Pathway

The TdpABC system employs a novel biochemical mechanism for sulfur incorporation into DNA:

- Activation Step: TdpC utilizes ATP to form an adenylated DNA intermediate, activating the phosphate backbone for nucleophilic attack [1]

- Substitution Step: The adenyl group is replaced with a sulfur atom, resulting in the definitive PT modification [1]

This two-step process represents a significant departure from previously characterized PT modification pathways and provides new insights into the evolutionary diversification of bacterial defense systems.

Table 1: Core Components of the TdpABC Defense System

| Component | Structure | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TdpC | Not specified | DNA sulfuration enzyme | Catalyzes two-step PT modification via adenylated intermediate |

| TdpA | Hexamer | DNA binding protein | Binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA in spiral staircase conformation |

| TdpB | Dimer | Nuclease | Degrades PT-free invading DNA |

Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination Mechanism

The TdpABC system employs a sophisticated recognition mechanism based on PT sulfur hydrophobicity to prevent autoimmune destruction of host DNA:

- PT modifications in self-DNA inhibit ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activity of TdpAB [1]

- The TdpAB-DNA interaction demonstrates sensitivity to sulfur hydrophobicity, enabling discrimination between modified and unmodified DNA [1]

- This mechanism provides protection against autoimmunity while maintaining effective defense against invasive genetic elements [1]

Structural Insights from Cryo-EM Analysis

Recent structural elucidation of the TdpABC complex has revealed fundamental aspects of its operational mechanism:

- The TdpA hexamer binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA through hydrogen bonds arranged in a spiral staircase conformation [1]

- This structural arrangement facilitates scanning of DNA for PT modifications while enabling rapid degradation of unmodified sequences

- The interaction interface demonstrates exquisite sensitivity to the hydrophobic properties of incorporated sulfur atoms, enabling precise self/non-self discrimination

Experimental Analysis of TdpABC

Key Experimental Protocols

Defense System Validation Assay

Purpose: To confirm anti-phage defense functionality of identified systems [2]

Procedure:

- Clone candidate open reading frames (ORFs) or operons into low-copy vectors under native promoter control

- Transform constructs into appropriate bacterial host strains (e.g., wild-type MG1655)

- Verify that systems do not affect phage adsorption through control experiments

- Challenge transformants with diverse phage panels at varying multiplicities of infection (MOI)

- Quantify protection through efficiency of plating (EOP) assays and plaque size analysis

Key Measurements:

- Efficiency of plating (EOP) = (Plaques on test strain) / (Plaques on phage-sensitive control strain)

- Plaque morphology and size distribution

- Determination of abortive infection (Abi) vs. direct immunity through growth assays at different MOIs

Functional Selection Screening

Purpose: Identification of novel anti-phage defense systems agnostic to genomic context [2]

Procedure:

- Construct large-insert fosmid libraries (∼40 kb fragments) from target genomic DNA

- Challenge library with lytic phages representing major Caudovirales classes in structured soft agar medium

- Isolate surviving colonies and sequence vector insert ends to identify genomic regions of origin

- Eliminate false positives through adsorption tests and restriction-modification phenotype recognition

- Generate sub-libraries (6-12 kb fragments) for defense system boundary mapping

- Sequence positive clones via long-read technologies to delineate system boundaries

Table 2: Quantitative Protection Profiles of Defense Systems

| Phage Challenge | Defense System | Efficiency of Plating (EOP) | Plaque Phenotype | Protection Breadth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | PD-T4-1 | <10⁻⁶ | No plaques | Narrow (T-even specific) |

| λvir | PD-λ-5 | ~10⁻⁴ | Reduced plaque size | Broad (9/10 phages) |

| T7 | PD-T7-1 | <10⁻⁵ | No plaques | Moderate |

| Multiple | PD-λ-5 | Variable reduction | Smaller plaques | Broad spectrum |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential research tools for investigating TdpABC and related defense systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TdpABC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Visualization | PyMOL, ChimeraX, UCSC Chimera, Cn3D [3] | 3D structure analysis of Tdp complexes and DNA interactions |

| 2D Visualization Tools | FlatProt [4] | Comparative analysis of protein structures across families |

| Cloning Vectors | Low-copy number plasmids, Fosmid vectors [2] | Stable maintenance of defense system operons |

| Phage Stocks | T4, λvir, T7, and diverse Caudovirales [2] | Challenge assays to determine defense system specificity |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM facilities [1] | High-resolution structural determination of DNA-protein complexes |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Foldseek [4] | Structural alignment and family classification of defense components |

Visualization of TdpABC Mechanism

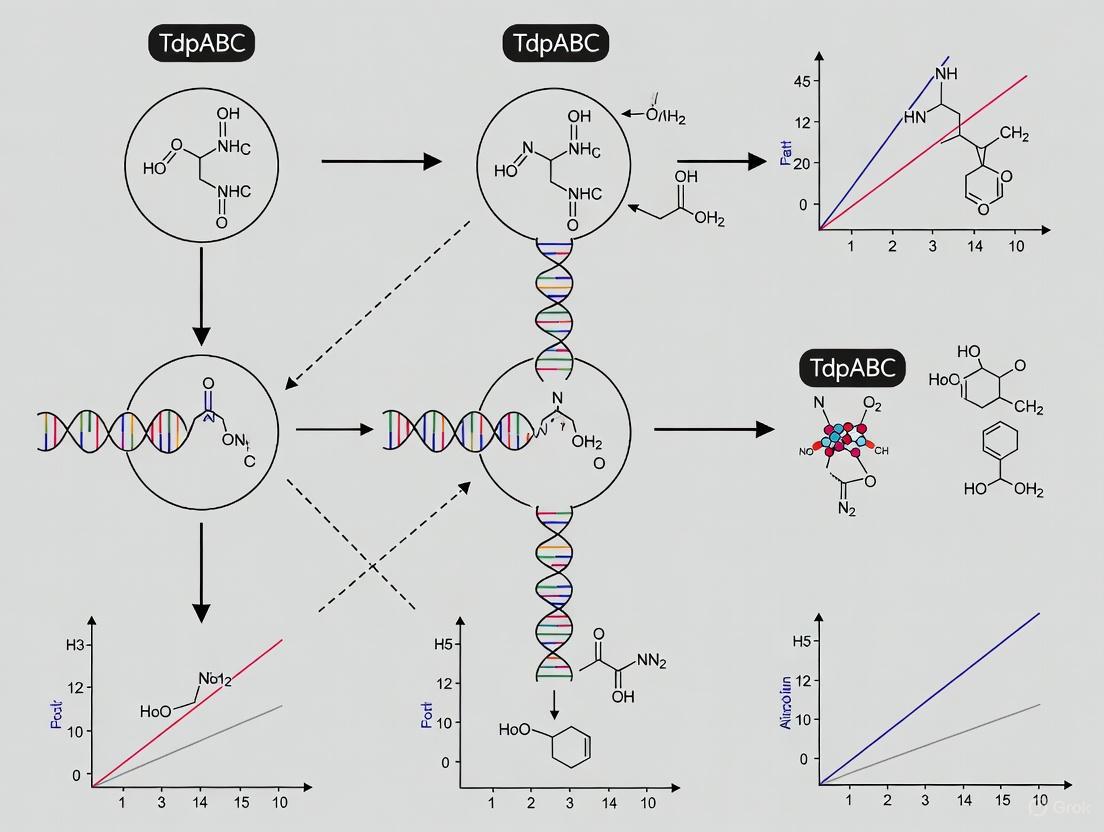

TdpABC Mechanism and Self/Non-Self Discrimination: This diagram illustrates the two-step sulfur incorporation pathway catalyzed by TdpC and the subsequent discrimination mechanism mediated by TdpAB. The system distinguishes self-DNA (PT-modified, green) from non-self phage DNA (unmodified, white) through sensitivity to sulfur hydrophobicity, selectively degrading only invasive genetic elements.

Research Applications and Future Directions

The TdpABC system presents compelling opportunities for both fundamental research and biotechnology development:

- Thermostable Enzymatic Tools: Components of the TdpABC system, functioning in extreme thermophiles, offer potential as thermostable reagents for molecular biology and DNA manipulation [5]

- Novel Antimicrobial Strategies: Understanding this defense mechanism may inform new approaches for controlling bacterial pathogens, particularly in conjunction with phage therapy [6]

- Synthetic Biology Applications: The hypercompact nature of TdpABC makes it an attractive candidate for engineering minimal defense systems in synthetic biological systems

- Evolutionary Insights: Comparative analysis of TdpABC with other defense systems provides windows into the evolutionary arms race between bacteria and their viral predators [2]

Future research directions should focus on structural characterization of the adenylated intermediate, detailed kinetic analysis of the two-step modification process, and engineering of TdpABC components for biotechnological applications. The exceptional thermal stability of this system offers particular promise for industrial processes requiring high-temperature DNA manipulation.

The TdpABC system represents a sophisticated bacterial defense mechanism against phage predation, discovered in extreme thermophiles. This system orchestrates a unique form of DNA modification known as phosphorothioation (PT), wherein a non-bridging oxygen atom in the DNA sugar-phosphate backbone is enzymatically replaced by a sulfur atom [1]. Unlike previously characterized PT modification systems, TdpABC employs a distinctive two-step chemical mechanism via an adenylated intermediate to achieve this sulfur incorporation, providing both offensive capability against invasive DNA and built-in safeguards to prevent autoimmune damage to host DNA [1] [7]. For researchers investigating bacterial immunity and potential therapeutic applications, understanding this mechanism offers insights into nature's solutions to pathogen recognition and neutralization.

The broader context of this research lies in the escalating biological arms race between bacteria and their viral predators (phages). With the recent discovery of hundreds of bacterial anti-phage defense systems, the TdpABC system stands out for its novel chemical strategy and self/non-self discrimination mechanism [8]. This system not only expands our understanding of microbial biochemistry but also presents potential applications in biotechnology, including the development of novel molecular tools and inspiration for new antimicrobial strategies.

Table: Key Components of the TdpABC Phosphorothioation System

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| TdpC | Catalyzes the two-step DNA phosphorothioation | Forms adenylated DNA intermediate, then substitutes with sulfur |

| TdpA | Forms hexameric translocase | Binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA in spiral staircase conformation |

| TdpB | Nuclease activity | Degrades PT-free phage DNA in dimeric form |

| TdpAB Complex | Provides anti-phage defense | Sensitive to hydrophobicity of PT sulfur; prevents self-DNA degradation |

Detailed Mechanism: The Two-Step Sulfur Incorporation Pathway

Step 1: Adenylation - DNA Activation

The initial activation step in the phosphorothioation pathway involves ATP-dependent adenylation of the DNA backbone. TdpC catalyzes the transfer of an adenyl group from ATP to the target oxygen atom on the DNA phosphate group, forming a high-energy adenylated intermediate [1]. This activation primes the DNA for subsequent sulfur incorporation by creating a more labile bond than the original phosphodiester linkage. The adenylation step represents a strategic biochemical solution to the challenge of modifying the inherently stable DNA backbone, providing the necessary driving force for the substitution reaction that follows.

Step 2: Sulfur Substitution - PT Modification Completion

The second step involves nucleophilic substitution where the adenyl group is displaced by a sulfur atom, resulting in the formation of the stable phosphorothioate modification [1]. The sulfur donor molecule, while not explicitly identified in the search results, is likely to be a cysteine derivative or other sulfur-containing metabolite. This substitution fundamentally alters the chemical properties of the DNA backbone, introducing a sulfur atom that increases hydrophobicity and creates a chiral center at phosphorus. The resulting PT modification serves as a molecular "self" marker that enables the host to distinguish its own DNA from invasive phage DNA lacking this modification.

Structural Insights: Molecular Architecture of Tdp Machinery

Cryo-EM Elucidation of the TdpAB-DNA Complex

High-resolution structural analysis via cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) at 2.76 Å resolution has revealed the molecular architecture of the TdpAB complex with DNA [7]. The structural data shows that TdpA forms a hexameric ring that encircles duplex DNA, binding one strand through hydrogen bonds arranged in a spiral staircase conformation [1]. This configuration enables the complex to translocate along DNA while scanning for the presence or absence of PT modifications. The TdpB component functions as a dimer, providing the nuclease activity that degrades non-self DNA lacking PT modifications [7].

The structural analysis further revealed that TdpAB-DNA interaction is exquisitely sensitive to the hydrophobicity of the PT sulfur [1]. This hydrophobicity sensing represents the critical mechanism for self/non-self discrimination, as the PT modifications on host DNA inhibit the ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activity of TdpAB, thereby preventing autoimmunity. When the complex encounters foreign DNA lacking the hydrophobic PT modifications, these inhibitory effects are lifted, allowing for DNA degradation and successful phage defense.

Table: Functional Consequences of DNA Modification Status on TdpAB Activity

| DNA Type | PT Modification Status | TdpAB Translocation | TdpAB Nuclease Activity | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-DNA | Contains hydrophobic PT modifications | Inhibited | Suppressed | Autoimmunity prevention |

| Non-self DNA | Lacks PT modifications | Activated | Enabled | Phage DNA degradation |

Biological Function: Anti-Phage Defense Mechanism

Integrated Phage Defense Model

The TdpABC system provides a coordinated defense mechanism through the complementary activities of its components. While TdpC establishes the PT modifications on host DNA, the TdpAB complex functions as the effector module that identifies and eliminates invading phage DNA [1]. The system operates on the principle of modification-dependent discrimination, where the presence of PT modifications serves as a "self" marker, similar in concept to restriction-modification systems but with a distinct chemical basis and recognition mechanism.

When phage DNA enters the cell, it lacks the PT modifications present on host DNA. The TdpAB complex scans incoming DNA, and upon encountering PT-free regions, it initiates degradation of the phage DNA, thereby aborting the infection [1]. This defense strategy represents an elegant solution to the challenge of distinguishing self from non-self in the context of nucleic acids. The system's effectiveness is evidenced by its conservation in extreme thermophiles, environments where maintaining genomic integrity against viral predation is particularly challenging.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Studying TdpABC

Key Experimental Protocols

Research on the TdpABC system has employed multidisciplinary approaches to elucidate its mechanism and function. Cryo-EM structural analysis was pivotal in determining the molecular architecture of the TdpAB-DNA complex [7]. This methodology involved purifying the native TdpAB complex, forming complexes with DNA substrates, flash-freezing samples, collecting high-resolution images, and performing three-dimensional reconstructions. The resulting structural data revealed the spiral staircase conformation of TdpA bound to DNA and provided insights into the mechanism of PT recognition.

Genetic and biochemical analyses were essential for characterizing the adenylation and sulfur substitution mechanism [1]. These approaches included in vitro reconstitution of the PT modification using purified TdpC components, ATP analog studies to trap the adenylated intermediate, and mass spectrometry analysis to verify sulfur incorporation. For functional assays, researchers employed phage challenge experiments to demonstrate the anti-phage activity of the system by comparing infection outcomes in strains with functional versus disrupted TdpABC systems.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for TdpABC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | Thermus antranikianii DSM 12462 | Source of native TdpABC components |

| DNA Substrates | Defined sequence DNA fragments | Testing modification specificity and efficiency |

| Nucleotide Analogs | ATPγS, α-^32P-ATP | Trapping and visualizing reaction intermediates |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM grids, Vitrification equipment | Determining high-resolution structures of complexes |

| Sulfur Sources | Cysteine derivatives, ^35S-labeled compounds | Tracing sulfur incorporation pathway |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Research Implications and Future Directions

The discovery of the two-step adenylation and sulfur substitution mechanism in the TdpABC system expands our fundamental understanding of DNA modification biology and bacterial immunity. From a biochemical perspective, this system reveals a novel strategy for post-synthetic DNA modification that differs fundamentally from more familiar methylation-based systems. The mechanistic insights gained from studying TdpABC may inspire new approaches in biotechnology and therapeutic development, particularly in the design of molecular tools that can distinguish between slightly different nucleic acid structures.

Future research directions include identifying the specific sulfur donor molecule utilized in the substitution reaction, elucidating the structural basis of TdpC catalysis, and exploring the potential applications of PT modification in molecular engineering. Additionally, investigation into how phages might evolve counter-defense strategies against TdpABC would provide further insights into the evolutionary dynamics of host-pathogen relationships. As our understanding of this system deepens, it may open new avenues for controlling microbial communities and developing novel antimicrobial strategies based on the principles of modification-dependent immune recognition.

DNA phosphorothioate (PT) modification, wherein a non-bridging oxygen atom in the DNA sugar-phosphate backbone is replaced by sulfur, represents a widespread epigenetic marker in prokaryotes. [1] This R-configuration modification is installed in a sequence-specific manner by various enzyme systems and has been implicated in multiple cellular functions, ranging from epigenetic regulation to defense against genetic parasites. [9] [10] The recent discovery of the TdpABC system in extreme thermophiles has revealed a novel PT-based antiphage defense mechanism with a unique chemical mechanism. [1] This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how DNA phosphorothioation systems, with a focused analysis on the Tdp machinery, function as sophisticated antiviral defense systems, and details the experimental approaches for their study.

The TdpABC system constitutes a hypercompact DNA phosphorothioation pathway that operates through a distinctive adenylated intermediate. [1] Coupled with the TdpAB effector complex, this system provides robust immunity against phage infection by selectively degrading PT-free foreign DNA while protecting modified self-DNA. This system exemplifies the ongoing molecular arms race between bacteria and their viral predators, and offers novel insights for therapeutic intervention and biotechnological application.

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Phosphorothioation

Diversity of PT Modification Systems

Prokaryotes employ several distinct protein systems to accomplish DNA phosphorothioation, each with characteristic genetic organization, modification patterns, and functional outcomes:

- Dnd Systems: The historically first-discovered system utilizes DndABCDE for double-stranded PT modification in consensus sequences such as 5′-GPSAAC-3′/5′-GPSTTC-3′ and 5′-GPSATC-3′/5′-GPSATC-3′. [11] These typically pair with restriction modules (DndFGH) that recognize and destroy non-PT-modified invasive DNA. [11]

- Ssp Systems: This more recently characterized system employs SspABCD for single-stranded PT modification exclusively at 5′-CPSCA-3′ motifs. [9] The restriction component SspE exhibits dual GTPase and DNA nicking activities that are stimulated by PT modification. [9]

- Tdp Systems: Found in extreme thermophiles, the TdpABC system represents a hypercompact PT pathway that functions via a novel adenylated intermediate mechanism. [1] It provides antiphage defense through the coordinated action of TdpC (modification) and TdpAB (restriction).

Table 1: Comparative Features of DNA Phosphorothioation Systems

| Feature | Dnd System | Ssp System | Tdp System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modification Type | Double-stranded | Single-stranded | Not Specified |

| Core Enzymes | DndA-E | SspA-D | TdpA-C |

| Restriction Component | DndFGH | SspE | TdpAB |

| Representative Motif | 5′-GPSAAC-3′ | 5′-CPSCA-3′ | Not Specified |

| Key Mechanism | Sequence-specific sulfur incorporation | PT-stimulated GTPase/nicking | Adenylated intermediate |

| Phage Defense | Degrades PT-free phage DNA | Nicking of non-PT DNA | PT-dependent degradation |

The TdpABC Pathway: A Novel Sulfuration Mechanism

Recent structural and biochemical analyses of the TdpABC system have elucidated a unique two-step mechanism for DNA phosphorothioation:

DNA Activation and Sulfur Incorporation

The TdpABC-mediated DNA sulfuration process occurs through two sequential steps:

- Activation: TdpC utilizes ATP to form an adenylated DNA intermediate, activating the DNA backbone for subsequent modification. [1]

- Substitution: The adenyl group is replaced with a sulfur atom, resulting in the final PT modification. [1]

This adenylated intermediate represents a previously unknown mechanism in biological DNA modification pathways and distinguishes TdpABC from other PT systems.

Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

The TdpAB restriction complex achieves specific targeting of non-self DNA through exquisite sensitivity to PT modifications:

- Cryogenic electron microscopy reveals that the TdpA hexamer binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA via hydrogen bonds arranged in a spiral staircase conformation. [1] [12]

- Critically, TdpAB-DNA interaction is sensitive to the hydrophobicity of the PT sulfur. [1]

- PT modifications in self-DNA inhibit ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activity of TdpAB, thereby preventing autoimmunity. [1]

- In contrast, PT-free phage DNA is actively translocated and degraded by the complex. [1]

The following diagram illustrates the TdpABC antiphage defense pathway:

Antiphage Defense Mechanisms and Efficacy

Protection Across Diverse Phage Types

DNA phosphorothioation systems provide broad-spectrum defense against various phage types through restriction of PT-free DNA:

- Lytic Phage Defense: Dnd-related restriction-modification systems confer protection against multiple lytic phages (T1, T4, T5, T7, and engineered E. coli phage EEP), with efficiency of plating (EOP) reductions of 1-5 orders of magnitude depending on the specific system. [11]

- Temperate Phage Interference: These systems effectively inhibit phage lysogenization but demonstrate limited efficacy against prophage induction once lysogeny is established. [11]

- Complementary Defense: Dnd and Ssp PT-related R-M systems function compatibly, with combined implementation providing additive suppression of phage replication through concurrent action. [11]

Quantitative Assessment of Antiphage Activity

Experimental quantification of phage resistance demonstrates the significant protective effect conferred by PT-based restriction systems:

Table 2: Antiphage Efficacy of Dnd Restriction-Modification Systems

| Phage Type | DndB7A R-M Protection | Dnd1166 R-M Protection | DndRED65 R-M Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Up to 10⁵-fold | 10¹-10³ fold | Weakest activity |

| T4 | Up to 10⁵-fold | 10¹-10³ fold | Weakest activity |

| T5 | Up to 10⁵-fold | 10¹-10³ fold | Weakest activity |

| T7 | Up to 10⁵-fold | 10¹-10³ fold | Weakest activity |

| EEP | Up to 10⁵-fold | 10¹-10³ fold | Weakest activity |

| Cocktails | Strong activity | MOI-dependent efficacy | Not specified |

The SspE Mechanism: PT-Dependent Activation

The Ssp system employs a sophisticated mechanism for self versus non-self discrimination through PT-sensing by the SspE effector:

- SspE is preferentially recruited to PT sites through the joint action of its N-terminal domain hydrophobic cavity and C-terminal domain DNA binding region. [9]

- PT recognition enlarges the GTP-binding pocket, enhancing GTP hydrolysis activity by approximately 2-fold. [9]

- This GTP hydrolysis triggers a conformational switch from a closed to open state, promoting SspE dissociation from self PT-DNA while activating the DNA nicking nuclease activity of the CTD. [9]

- The system remains effective even when only 14% of modifiable consensus sequences are PT-protected in a bacterial genome. [9]

The following diagram illustrates this PT-sensing mechanism:

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The study of DNA phosphorothioation systems requires specialized reagents and molecular tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PT Modification Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| pACYC184 Vector | Cloning and expression of dnd gene clusters | Antiphage spectrum analysis [11] |

| LC-MS/MS | Detection and quantification of PT modifications (d(GPSA), d(GPST)) | Modification motif identification [11] |

| EOP Assays | Quantitative measurement of phage restriction efficiency | Determination of protection levels (orders of magnitude reduction) [11] |

| Cryo-EM | High-resolution structural analysis of protein-DNA complexes | TdpAB-DNA interaction studies [1] [12] |

| AMPPNP | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog for trapping intermediate states | Structural studies of TdpAB complex [12] |

| SeMet Derivatives | Phasing for X-ray crystallography | SspE structure determination [9] |

| FRET Measurements | Monitoring conformational changes in real-time | SspE closed-to-open transition studies [9] |

Structural Biology Protocols

Cryo-EM Analysis of TdpAB-DNA Complex

The structural characterization of TdpAB in complex with DNA and AMPPNP provides critical insights into its mechanism:

Sample Preparation:

- Express TdpA and TdpB from Thermus antranikianii in E. coli BL21(DE3). [12]

- Purify complexes using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Incubate TdpAB with AMPPNP (non-hydrolyzable ATP analog) and dsDNA oligonucleotides (5′-D(PGPCPCPCPTPTPTPTPGPCPAPA)-3′ and complementary strand). [12]

- Vitrify samples using standard plunge-freezing protocols.

Data Collection and Processing:

- Collect cryo-EM data using modern TEM with K3 direct electron detector.

- Process images through standard single-particle analysis workflow:

- Motion correction and dose-weighting

- CTF estimation

- Particle picking and extraction

- 2D classification

- 3D classification and refinement

- Achieve resolution of 2.67 Å sufficient for atomic model building. [12]

- Build and refine atomic models using Coot and Phenix. [12]

Crystallographic Analysis of SspE

Crystallization and Structure Determination:

- Express and purify full-length SspE from Streptomyces yokosukanensis and SspECTD from Streptomyces scabiei. [9]

- Generate SeMet derivatives for experimental phasing.

- Crystallize using vapor diffusion methods.

- Collect X-ray diffraction data and solve structure using SAD method. [9]

- Refine structures to Rwork/Rfree values of 20.1%/27.6% at 3.4 Å resolution. [9]

Biochemical and Functional Assays

GTPase Activity Measurements

Procedure for PT-Stimulated GTPase Assay:

- Prepare reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂).

- Incubate SspE (2 µM) with GTP (1 mM) in presence or absence of PT-modified DNA fragments (5′-CPSCA-3′ containing). [9]

- Include appropriate mutant controls (SspEY30A, SspEQ31A). [9]

- Quantify phosphate release using malachite green assay at 620nm.

- Calculate stimulation factor by comparing rates with and without PT-DNA.

DNA Nicking Assay

Nuclease Activity Assessment:

- Incubate SspE with supercoiled plasmid DNA in reaction buffer.

- Include essential divalent cations (Mg²⁺) and compare to EDTA-treated controls. [9]

- Test HNH motif mutants (SspEN676A) to confirm catalytic residues. [9]

- Separate reaction products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Quantify nicked circular versus supercoiled DNA using ImageJ software. [13]

In Vivo Antiphage Protection Assays

Efficiency of Plating (EOP) Determination:

- Introduce PT R-M systems via plasmid vectors (e.g., pACYC184) into appropriate host strains. [11]

- Prepare serial dilutions of phage lysates (T1, T4, T5, T7, EEP).

- Spot phage dilutions on lawns of PT R-M-containing and control strains.

- Incubate overnight at appropriate temperature.

- Calculate EOP as (PFU on restrictive host)/(PFU on permissive host). [11]

- Classify protection levels based on EOP reduction (1-5 orders of magnitude). [11]

Liquid Culture Protection Assays:

- Inoculate bacterial cultures containing PT R-M systems and control strains.

- Infect with phages at varying MOIs (0.01-10). [11]

- Monitor OD600 over time to assess culture collapse prevention.

- Compare protection patterns across different phage types. [11]

Additional Biological Roles of DNA Phosphorothioation

Beyond antiphage defense, DNA phosphorothioation contributes to other physiological functions:

Oxidative Stress Resistance

PT modifications confer protection against reactive oxygen species through a unique antioxidant mechanism:

- In Vivo Protection: dnd+ E. coli strains exhibit significantly lower 8-OHdG levels and ROS accumulation under oxidative stress compared to dnd- mutants. [13]

- Hydroxyl Radical Specificity: PT modifications demonstrate exceptional capacity to quench hydroxyl radicals through a proposed mechanism involving electron donation and generation of reductive HS• species. [13]

- Peroxide Resistance: Streptomyces lividans with PT modification shows 2-10 fold higher survival following peroxide treatment compared to dnd- mutants. [10]

Regulation of Horizontal Gene Transfer

PT-based restriction systems influence antimicrobial resistance gene acquisition:

- Strains equipped with PT R-M systems harbor fewer plasmid-derived, prophage-derived, and mobile element-related AMR genes. [14]

- The presence of PT R-M effectively reduces horizontal gene transfer frequency, potentially suppressing dissemination of antibiotic resistance. [14]

- In Klebsiella pneumoniae, PT R-M systems significantly reduce AMR gene acquisition (25.64% fewer genes compared to PT R-M-defective strains). [14]

DNA phosphorothioation represents a multifaceted epigenetic system with crucial functions in prokaryotic antiviral defense. The recently characterized TdpABC system from extreme thermophiles reveals a novel adenylate intermediate pathway for sulfur incorporation into DNA, expanding the mechanistic diversity of PT-based modification systems. These systems achieve remarkable discrimination between self and non-self DNA through sophisticated molecular recognition of PT modifications, enabling specific degradation of invading genetic elements while protecting host genomes.

The experimental methodologies detailed in this whitepaper—from structural characterization of protein-DNA complexes to functional assessment of antiphage activity—provide researchers with comprehensive tools for investigating these complex systems. As the molecular arms race between bacteria and phages continues to drive evolutionary innovation, DNA phosphorothioation systems offer both fascinating subjects for fundamental research and potential applications in biotechnology and therapeutic development. Future studies will undoubtedly uncover additional complexity in these systems and may reveal new opportunities for manipulating host-pathogen interactions.

This whitepaper examines the TdpABC system, a unique DNA phosphorothioation-based phage defense mechanism recently discovered in thermophilic bacteria and archaea. We explore the hypothesis that the extreme thermal environments in which thermophiles thrive have driven the evolution of this specialized, multi-component defense system. The analysis covers its molecular mechanism, ecological significance, and experimental approaches for its study, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical overview of this emerging biological system with potential biotechnology applications.

Thermophiles, microorganisms thriving at temperatures above 45°C, inhabit ecological niches such as hot springs, geothermal fields, and arid sands where temperatures can exceed 70°C [15] [16]. These extreme environments create unique evolutionary pressures, particularly regarding genome stability and defense mechanisms against viral predators.

While thermophiles face constant threat from bacteriophages (phages) in these habitats, their high-temperature environment may paradoxically influence phage dynamics. The thermostability of macromolecules becomes a critical factor in the arms race between host and virus [17]. The TdpABC system represents a recently discovered defense mechanism that appears specifically optimized for these conditions, utilizing DNA phosphorothioation (PT) - the replacement of a non-bridging oxygen in the DNA backbone with sulfur - to distinguish self from non-self DNA [1] [18].

Table 1: Characteristics of Thermophilic Environments Harboring Novel Defense Systems

| Environment Type | Temperature Range (°C) | Sample Locations | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geothermal Fields | 60-85 | El Tatio (Chile), Jurasi Hot Springs (Chile) | Geobacillus, Parageobacillus [16] |

| Arid Sands | 53.5-61.4 | Aïn Sefra (Algeria) | Geobacillus kaustophilus [15] |

| Coastal Lagoons | 45-70 | Laguna Tebenquiche, Laguna Cejar (Chile) | Anoxybacillus, Aeribacillus [16] |

Molecular Mechanism of the TdpABC System

Core Components and Unique Two-Step Sulfur Incorporation

The TdpABC system represents a hypercompact DNA phosphorothioation pathway discovered in extreme thermophiles [1]. Unlike previously characterized PT systems, TdpABC operates through a distinctive adenylated intermediate during the sulfur incorporation process:

- TdpC: Catalyzes the initial activation step using ATP to form an adenylated DNA intermediate

- TdpC (continued): Subsequently mediates the substitution of the adenyl group with a sulfur atom

- TdpA: Forms a hexameric complex that binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA

- TdpB: Functions as a dimer alongside TdpA in the defense complex [1] [18]

Structural analysis via cryogenic electron microscopy has revealed that the TdpA hexamer binds DNA through hydrogen bonds arranged in a spiral staircase conformation, enabling precise interaction with the modified DNA backbone [1].

Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination Mechanism

A critical feature of the TdpABC system is its sophisticated mechanism for distinguishing host DNA from invading phage DNA:

- PT Modification of Self-DNA: The host bacterium's DNA contains phosphorothioate modifications introduced by TdpC

- Sulfur Hydrophobicity Sensing: The TdpAB complex is sensitive to the hydrophobicity of the PT sulfur

- Inhibition of Autoimmunity: PT modifications inhibit ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activity of TdpAB on self-DNA

- Degradation of Invading DNA: PT-free phage DNA remains vulnerable to degradation by the TdpAB complex [1]

This mechanism provides anti-phage defense while preventing autoimmune destruction of the host genome, a crucial adaptation for survival in extreme environments.

Ecological Drivers in Thermophilic Environments

Environmental Pressures and System Evolution

The thermal ecosystems inhabited by thermophiles create unique conditions that likely favored the evolution of specialized defense systems like TdpABC:

- High Viral Load: Thermal environments maintain diverse phage populations despite elevated temperatures

- Macromolecular Stability: Both host and phage biomolecules must maintain stability at high temperatures, potentially constraining evolutionary options for defense and counter-defense [17]

- Energy Constraints: Thermophiles often inhabit nutrient-limited extreme environments, favoring energy-efficient defense mechanisms [19]

The resource-intensive nature of DNA phosphorothioate modification suggests significant evolutionary benefit to this defense strategy in thermal environments, possibly related to its durability and specificity under high-temperature conditions.

Comparative Analysis with Mesophilic Systems

DNA phosphorothioation systems exist in mesophilic bacteria, but the TdpABC system shows distinctive adaptations:

- Hypercompact Architecture: Streamlined for genetic efficiency

- Adenylated Intermediate: Unique to the thermophilic system

- Thermostable Components: Protein structures optimized for high-temperature function [1]

These differences highlight the niche-specific evolution of defense mechanisms and underscore how environmental constraints shape molecular adaptations.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Isolation and Cultivation of Thermophilic Strains

Sample Collection from Extreme Environments:

- Collect sediment or water samples aseptically from geothermal sites

- Maintain samples at 4°C during transport to preserve viability [15] [16]

- Record in-situ temperature and pH measurements at collection sites

Enrichment and Isolation:

- Use thermophile-specific media such as:

- Incubate at 60-70°C for 24-48 hours under aerobic or anaerobic conditions depending on target organisms

- Streak cultures onto solid media supplemented with 2% agar for colony isolation

- Purify through successive subculturing to obtain axenic strains [15]

Genetic and Biochemical Characterization

DNA Modification Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA from thermophilic strains using high-temperature compatible protocols

- Detect phosphorothioate modifications through:

- HPLC-MS/MS for PT quantification

- RPPA (Restriction Endonuclease Protection Assay) to map modification sites [1]

Protein Complex Characterization:

- Express recombinant TdpA, TdpB, and TdpC components in suitable vectors

- Purify complexes using affinity chromatography under native conditions

- Analyze structures via cryo-EM as performed in the foundational TdpABC study [1]

- Conduct ATPase and nuclease activity assays to characterize enzymatic functions

Phage Defense Assays:

- Isplicate native thermophilic phages from the same environment

- Conduct plaque assays to quantify phage inhibition by wild-type versus TdpABC-mutant strains

- Measure phage DNA degradation kinetics in the presence of TdpAB complex [17]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for TdpABC System Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Natural Tatio Media (NTM), Modified Liquid Medium (MLM) | Isolation and cultivation of thermophilic bacteria [15] [16] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Genomic DNA extraction kits (high-temperature compatible) | DNA extraction for PT modification analysis [1] |

| Expression Systems | pET vectors, thermophilic expression hosts | Recombinant production of Tdp proteins [1] |

| Chromatography | Ni-NTA affinity columns, size exclusion columns | Protein complex purification [1] |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM grids, negative stains | Structural characterization of Tdp complexes [1] |

| Enzyme Assays | ATPase activity kits, nuclease activity kits | Functional characterization of Tdp components [1] |

Research Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Research workflow for characterizing TdpABC systems

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanism of TdpABC phage defense

Discussion: Biotechnological Implications and Future Directions

The discovery of the TdpABC system opens several promising avenues for biotechnology and therapeutic development:

- Novel Antimicrobial Strategies: Components of the TdpABC system could be engineered as sequence-independent nucleases with applications against multi-drug resistant bacteria

- Molecular Tool Development: The system's unique recognition mechanism could inspire new DNA detection and manipulation technologies

- Phage Therapy Enhancement: Understanding bacterial defense mechanisms enables development of engineered phages that evade host defenses [20] [17]

Future research should focus on:

- Structural characterization of the adenylated DNA intermediate

- Engineering TdpAB complexes with altered sequence specificity

- Investigating system prevalence across diverse thermophilic taxa

- Developing high-throughput screening for PT modifications

The TdpABC phosphorothioation system represents a sophisticated adaptation to the unique ecological challenges faced by thermophiles in their extreme habitats. Its two-step sulfur incorporation mechanism, sensitivity to PT hydrophobicity, and discrimination between self and non-self DNA illustrate how environmental pressures drive molecular innovation. Continued investigation of this system will not only advance our understanding of host-phage dynamics in extreme environments but may also yield valuable tools for biotechnology and therapeutic development.

Structural Insights and Biotechnological Applications of the TdpABC Machinery

The TdpABC system represents a recently discovered and hypercompact bacterial defense mechanism that provides protection against phage infection in extreme thermophiles. This system operates through a sophisticated molecular machinery that incorporates sulfur into the DNA backbone and selectively degrades invading genetic material. Central to this defense system is the TdpAB complex, a multi-protein assembly that functions as the executive component, discerning self from non-self DNA and enacting the destructive response against foreign phage DNA. Research published in 2025 has illuminated the structure and mechanism of this complex through cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), revealing an intricate architecture that explains its unique functionality [7] [1] [21]. The structural insights provided by these studies have not only elucidated a novel anti-phage defense strategy but have also uncovered a previously unknown DNA modification pathway with significant implications for understanding prokaryotic epigenetics and host-pathogen interactions.

Structural Elucidation of the TdpAB Complex

The TdpAB complex exhibits a meticulously organized quaternary structure, with distinct roles for its component subunits. Cryo-EM analysis reveals that TdpA forms a hexameric ring structure that serves as the central scaffold and functional core of the complex [7] [21]. This hexameric arrangement is characteristic of many nucleic acid processing enzymes, as it provides a symmetrical platform for engaging DNA substrates. Associated with this central ring is TdpB, which functions as a dimeric nuclease, poised to execute the cleavage of target DNA upon activation [1] [21]. The entire complex has a substantial molecular weight of approximately 485 kDa, reflecting its multi-subunit composition and functional complexity [7]. This structural organization enables the complex to perform its dual functions of DNA translocation and degradation in a coordinated manner.

Table 1: Cryo-EM Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for TdpAB Structures

| Parameter | TdpAB Complex (8WET) | TdpAB with AMPPNP and DNA (8WFD) |

|---|---|---|

| PDB Accession | 8WET | 8WFD |

| EMDB Accession | EMD-37479 | EMD-37491 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.76 | 2.67 |

| Biological Source | Thermus antranikianii DSM 12462 | Thermus antranikianii DSM 12462 |

| Experimental Method | Single-particle cryo-EM | Single-particle cryo-EM |

| Total Molecular Weight | 484,791.92 Da | 493,635.31 Da |

| Release Date | 2025-01-22 | 2025-01-22 |

| Primary Citation | An et al., Nat Chem Biol 21:1160-1170 (2025) | An et al., Nat Chem Biol 21:1160-1170 (2025) |

The Spiral Staircase DNA Binding Mechanism

One of the most striking revelations from the cryo-EM structures is the unique mode of DNA engagement employed by the TdpA hexamer. The complex encircles duplex DNA and binds to a single strand through hydrogen bonds arranged in what researchers have described as a spiral staircase conformation [7] [21]. This architectural motif allows for sequential interactions with the DNA backbone, facilitating both recognition and processive movement along the substrate. The spiral staircase arrangement is particularly suited for monitoring the chemical properties of the DNA backbone, enabling the complex to detect the presence or absence of phosphorothioate modifications with high fidelity. This discrimination capability is fundamental to the system's ability to target foreign DNA while sparing the host genome.

Structural Basis for Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

The TdpAB complex exhibits remarkable sensitivity to the hydrophobicity of the phosphorothioate sulfur atom [1] [21]. This physicochemical property serves as the molecular signature for self-DNA, which contains these modifications installed by the TdpC component of the system. The structural analysis reveals that PT modifications inhibit the ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activities of TdpAB on self-DNA, thereby preventing autoimmune reactions [7] [21]. In contrast, PT-free DNA, characteristic of invading phage genomes, fails to trigger this inhibitory effect, leaving it vulnerable to the complex's degradative capabilities. This mechanism represents an elegant solution to the fundamental challenge faced by all immune systems: the reliable distinction between self and non-self molecules.

Functional Workflow of the TdpABC System

The TdpABC system operates through a coordinated, multi-step process that begins with DNA modification and culminates in targeted degradation of foreign genetic material. The cryo-EM structures of various functional states of the TdpAB complex have enabled researchers to piece together this molecular workflow in unprecedented detail.

Diagram 1: Functional workflow of the TdpABC phage defense system (Title: TdpABC Phage Defense Mechanism)

The structural basis for this workflow is illuminated by the cryo-EM structures, which capture different functional states of the complex. The TdpA hexamer's spiral staircase conformation enables it to physically interrogate the DNA backbone, while the associated TdpB nuclease remains restrained until PT-free DNA is encountered. The inhibition of ATP-driven translocation on PT-modified DNA represents a key regulatory checkpoint that prevents autoimmunity, and this allosteric control mechanism is embedded in the complex's three-dimensional architecture [7] [1] [21].

Materials and Methods: Technical Framework

Cryo-EM Structure Determination Protocol

The elucidation of the TdpAB complex architecture relied on state-of-the-art single-particle cryo-EM methodologies. The experimental workflow encompassed sample preparation, data collection, image processing, and model building, each stage requiring specialized techniques and equipment to achieve the high resolutions necessary for mechanistic insights.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Specification/Composition | Functional Role in Study |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Source | Thermus antranikianii DSM 12462 | Source of native TdpAB complex for structural studies |

| Expression System | Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) | Recombinant protein production |

| DNA Substrates | Double-stranded DNA with and without PT modifications | Functional assays and complex stabilization for cryo-EM |

| Nucleotide Analogs | AMPPNP (non-hydrolyzable ATP analog) | Trapping translocation-competent states of TdpAB complex |

| Cryo-EM Grids | UltrAuFoil or Quantifoil with thin carbon | Sample support for vitrification and high-resolution imaging |

| Vitrification System | Vitrobot Mark IV (or equivalent) | Rapid plunging freezing for specimen preservation |

Sample Preparation and Grid Preparation

The TdpAB complex was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and purified using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography [22]. For structural studies, the complex was mixed with DNA substrates—both with and without phosphorothioate modifications—and in some cases with the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPNP to trap specific conformational states [21] [23]. The samples were applied to cryo-EM grids, blotted to remove excess liquid, and vitrified by rapid plunging into liquid ethane using devices such as the Vitrobot Mark IV. This process preserves the native structure of the complexes in a thin layer of amorphous ice, essential for high-resolution imaging [24].

Data Collection and Image Processing

Cryo-EM data were collected on advanced electron microscopes, likely Titan Krios or similar instruments, equipped with high-speed direct electron detectors [24]. Data collection parameters typically included a total electron dose of ~50 e⁻/Ų, distributed across multiple frames to facilitate motion correction [24]. The resulting datasets comprised thousands of micrographs, which were processed using sophisticated software pipelines such as RELION or cryoSPARC [24] [25]. The processing workflow involved particle picking, 2D classification, ab initio reconstruction, 3D classification, and high-resolution refinement. The gold-standard Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC=0.143) criterion was used to determine the final resolution of the reconstructions [26]. For the TdpAB complex, this process yielded structures at 2.76 Å (PDB: 8WET) and 2.67 Å (PDB: 8WFD) resolution, sufficient for discerning secondary structure elements and side-chain orientations [7] [23].

Diagram 2: Cryo-EM structure determination pipeline (Title: Cryo-EM Structure Determination Workflow)

Model Building and Refinement

Atomic models were built into the cryo-EM density maps using a combination of de novo model building and homologous structure docking. The high resolution of the maps (2.67-2.76 Å) allowed for the placement of most amino acid side chains and the identification of key DNA-protein interactions [7] [23]. The models were refined using programs such as REFMAC5 or Phenix with geometry restraints to maintain proper stereochemistry while maximizing the fit to the EM density [24]. The final validated models were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 8WET (TdpAB complex) and 8WFD (TdpAB with AMPPNP and DNA) [7] [22] [23].

Discussion: Implications and Future Directions

Mechanistic Insights into DNA Phosphorothioation Systems

The structural revelations of the TdpAB complex provide a mechanistic framework for understanding the broader family of DNA phosphorothioation-based defense systems. The spiral staircase DNA binding mode represents a novel architecture for DNA modification-dependent restriction systems, distinct from the typical restriction endonuclease folds [21]. The allosteric inhibition conferred by phosphorothioate modifications offers a paradigm for how enzymes can evolve sensitivity to epigenetic marks, enabling them to discriminate between structurally similar substrates based on subtle physicochemical differences. This principle may extend to other modification-dependent restriction systems and even eukaryotic epigenetic readers.

Biotechnological and Therapeutic Applications

The structural insights from the TdpAB complex have significant potential for biotechnological exploitation. The system's ability to selectively degrade unmodified DNA while sparing PT-modified DNA suggests applications in molecular cloning and DNA engineering, where selective digestion of background DNA could enhance efficiency [1] [21]. Furthermore, understanding the molecular basis of anti-phage defense systems opens avenues for developing phage-based therapies to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The detailed architecture of the TdpA hexamer could inform the design of novel DNA-manipulating enzymes for sequencing or nanotechnological applications.

Technical Advancements in Cryo-EM Methodology

The determination of the TdpAB complex structures at 2.67-2.76 Å resolution exemplifies the continuing advancement of cryo-EM methodologies. While these resolutions do not reach the true atomic resolution (1.5 Å or better) demonstrated for ideal specimens like apoferritin [24] [25], they represent robust achievements for a complex biological assembly without high symmetry. The successful structure determination of the TdpAB complex underscores how cryo-EM has become a routine tool for elucidating the architecture of macromolecular complexes that are challenging to study by other methods, particularly those with conformational heterogeneity or membrane-associated components [24] [25] [26].

The cryo-EM structures of the TdpAB complex have unveiled the architectural principles underlying a novel bacterial defense system that thrives in extreme environments. The revelations of the spiral staircase DNA binding mechanism, the phosphorothioate-dependent allosteric regulation, and the coordinated action of translocation and nuclease activities provide a comprehensive mechanistic understanding of how thermophiles defend against phage predation. These structural insights not only advance our fundamental knowledge of host-pathogen interactions but also showcase the power of contemporary cryo-EM methodologies to resolve complex biological questions at molecular resolution. As cryo-EM technology continues to evolve, promising even higher resolutions and the ability to capture dynamic processes [24] [25], we can anticipate further revelations about the sophisticated molecular machines that govern life at the extremes.

The TdpABC system represents a paradigm-shifting discovery in prokaryotic antiviral defense, employing a unique DNA modification and recognition mechanism. Central to this system is the TdpA helicase, which forms a hexameric molecular motor adopting a spiral staircase conformation to engage duplex DNA. This structural arrangement is critical for the system's ability to distinguish self from non-self DNA, providing a potent defense against phage infection in thermophiles. Through a combination of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structural analysis and biochemical assays, researchers have elucidated how this architecture enables ATP-driven translocation along DNA while maintaining specificity for phosphorothioate-modified nucleotides. This whitepaper details the structural basis and functional implications of TdpA's DNA engagement mechanism, providing technical guidance for researchers investigating bacterial immunity and nucleic acid-protein interactions.

The TdpABC system constitutes a hypercompact bacterial defense mechanism discovered in extreme thermophiles that protects against phage infection through a sophisticated molecular strategy. This system operates via a two-step modification process: first, TdpC activates the DNA backbone through adenylation, then incorporates a sulfur atom to create phosphorothioate (PT) modifications [1]. These PT modifications serve as molecular "self" markers that distinguish host DNA from invading phage DNA.

The system's defensive capability hinges on the TdpAB complex, which functions as a discrimination machinery that selectively degrades PT-free foreign DNA while sparing modified self-DNA [1]. This self/non-self discrimination represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that prevents autoimmunity while maintaining effective antiviral defense. The entire process is particularly noteworthy for its occurrence in thermophilic environments, where elevated temperatures present additional challenges for molecular recognition and enzymatic activity.

Structural Architecture of the TdpA Hexamer

The TdpA component assembles into a hexameric ring complex that engages duplex DNA in a distinctive spiral staircase arrangement. Cryo-EM structural analysis reveals that the TdpA hexamer binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA through hydrogen bonds arranged in this spiral conformation [1]. This structural organization shares similarities with other hexameric helicases like DnaB, which also forms a double-layered, right-handed spiral staircase when complexed with ssDNA [27], yet exhibits unique adaptations specific to its role in PT-based phage defense.

The spiral staircase formation enables asymmetric engagement with the DNA substrate, with individual subunits positioned at different heights relative to the DNA helix axis. This arrangement facilitates sequential nucleotide binding and hydrolysis, powering the translocation of DNA through the central channel of the hexameric ring.

DNA Binding Mechanism

The TdpA hexamer establishes extensive contacts with the phosphorothioated DNA substrate through its central channel, which accommodates duplex DNA in a sequence-independent manner. Structural data from the TdpAB complex with AMPPNP and PT-DNA (PDB ID: 8Y1K) reveals that the complex engages DNA through a combination of:

- Hydrogen bonding networks between protein side chains and DNA backbone [1]

- Hydrophobic interactions with the PT sulfur atoms [1]

- Electrostatic contacts with phosphate groups

The binding interface exhibits remarkable sensitivity to PT modifications, with the hydrophobicity of the incorporated sulfur atom playing a critical role in modulating the strength of protein-DNA interactions [1]. This PT-sensing capability forms the structural basis for self/non-self discrimination.

Table 1: Key Structural Features of TdpA Hexamer

| Structural Feature | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Quaternary Structure | Hexameric ring | Forms central channel for DNA engagement |

| DNA Binding Conformation | Spiral staircase | Enables sequential ATP hydrolysis and translocation |

| PT Recognition Site | Hydrophobic pocket | Distinguishes modified self-DNA from non-modified foreign DNA |

| Subunit Arrangement | Asymmetric spiral | Coordinates sequential mechanochemical activities |

Functional Mechanism of DNA Engagement

ATP-Driven Translocation

The TdpA hexamer operates as a molecular motor that couples ATP hydrolysis to directional movement along DNA. The spiral staircase conformation enables a revolving mechanism where individual subunits undergo cyclic conformational changes that propel the hexamer along the DNA substrate [28]. This mechanism differs from rotational models and instead involves a hand-over-hand movement where subunits sequentially advance along the helical axis.

The translocation mechanism exhibits several distinctive characteristics:

- Directional preference for 5'→3' movement along the engaged DNA strand [28]

- Step size of approximately two nucleotides per subunit cycle [27]

- ATP hydrolysis coordination through sequential action of subunits [27]

- Inchworm-like progression that minimizes dissociation from the DNA substrate

Self/Non-Self Discrimination

The most remarkable feature of TdpAB DNA engagement is its ability to discriminate PT-modified DNA from unmodified DNA. This discrimination sensitivity is attributed to the hydrophobic character of the sulfur atom incorporated in PT modifications [1]. The structural basis for this recognition involves:

- Differential binding affinity for PT-modified versus unmodified DNA

- Allosteric regulation of nuclease activity based on PT detection

- Autoinhibition of translocation when PT modifications are encountered

This discriminatory capability ensures that TdpAB selectively degrades invading phage DNA while sparing the host's modified genome, thereby preventing autoimmune destruction of the bacterial cell [1].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Cryo-EM Structure Determination

The structural insights into TdpA-DNA engagement were primarily obtained through single-particle cryo-EM. Key experimental details include:

Sample Preparation:

- Source organism: Thermus antranikianii DSM 12462 [29]

- Expression system: Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) [29]

- Complex formation: TdpAB with AMPPNP (ATP analog) and PT-DNA [29]

Data Collection and Processing:

- Resolution achieved: 3.10 Å [29]

- Reconstruction method: Single-particle analysis [29]

- EMDB accession: EMD-38837 [29]

- PDB ID: 8Y1K [29]

The structure determination revealed the TdpA hexamer in complex with a 12-basepair DNA duplex containing site-specific phosphorothioate modifications [30]. The asymmetric spiral staircase arrangement of subunits was clearly resolved, providing atomic-level insights into the DNA engagement mechanism.

Functional Assays

Complementary biochemical approaches validated the structural findings:

ATPase Activity Measurements:

- Quantified ATP hydrolysis rates in presence of PT-modified versus unmodified DNA

- Demonstrated PT-dependent regulation of enzymatic activity [1]

Nuclease Protection Assays:

- Measured degradation kinetics of modified and unmodified DNA substrates

- Established correlation between PT modification and resistance to degradation [1]

Translocation Monitoring:

- Tracked protein movement along DNA templates using single-molecule approaches

- Confirmed directionality and step size of TdpA movement [1]

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for TdpAB Structural Studies

| Parameter | TdpAB Complex (PDB: 8Y1K) | TdpAB Complex (PDB: 8WET) |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 3.10 Å [29] | 2.76 Å [7] |

| DNA Substrate | 12-bp PT-modified duplex [29] | Not specified |

| Nucleotide Analog | AMPPNP [29] | Not specified |

| Organism | Thermus antranikianii [29] | Thermus antranikianii [7] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for investigating TdpA-DNA interactions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TdpABC Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| TdpAB Complex | Structural and functional studies | Heterocomplex from Thermus antranikianii [29] |

| PT-Modified DNA | Substrate for engagement studies | Site-specific phosphorothioate modifications [29] |

| AMPPNP | ATP hydrolysis analysis | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog [29] |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Structural determination | UltrAuFoil or Quantifoil grids [29] |

| Thermophilic Expression System | Protein production | E. coli BL21(DE3) with optimized codons [29] |

Visualizing the Spiral Staircase Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the spiral staircase conformation of TdpA hexamer and its engagement with duplex DNA:

Diagram 1: TdpA Hexamer Spiral Staircase DNA Engagement

The experimental workflow for investigating TdpA-DNA interactions encompasses multiple technical approaches:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for TdpA-DNA Interaction Studies

Implications for Antimicrobial Development

The structural insights into TdpA-DNA engagement offer promising avenues for therapeutic innovation. Several aspects of this system present potential applications:

Novel Antibiotic Targets:

- The PT-sensing mechanism could inspire selective inhibitors targeting pathogenic bacterial defense systems

- The spiral staircase conformation represents a unique structural motif for small-molecule intervention

Diagnostic Applications:

- PT recognition principles could be adapted for molecular detection of bacterial infections

- The discriminatory mechanism informs biosensor design for pathogen identification

Biotechnological Tools:

- The TdpAB system could be engineered for sequence-specific DNA targeting

- The PT-dependent nuclease activity might be harnessed for genome editing applications

Understanding the precise molecular details of how TdpA engages DNA through its spiral staircase conformation not only illuminates fundamental biological processes but also opens new frontiers for combating antimicrobial resistance and developing advanced molecular tools.

Harnessing TdpABC for Synthetic Biology and Robust Industrial Strains

The rising global bioeconomy, projected to be worth $30 trillion by 2030, necessitates the development of robust, high-performing industrial microbial strains that can resist phage contamination and maintain stable production in large-scale bioreactors [31]. The recent discovery of the TdpABC system—a hypercompact DNA phosphorothioation-based defense system from extreme thermophiles—offers a powerful new toolkit for synthetic biologists and metabolic engineers. This system provides a unique two-step anti-phage defense mechanism: it first places a sulfur-based "self" marker on the host's DNA backbone, then selectively degrades invading "non-self" DNA that lacks this modification [1] [32]. This sophisticated self versus non-self discrimination capability, combined with its origin in robust thermophilic organisms, makes TdpABC particularly promising for engineering resilient industrial microbes capable of withstanding the harsh conditions and contamination risks of biomanufacturing environments. This technical guide explores the mechanistic basis of TdpABC and provides a practical framework for its implementation in synthetic biology applications.

Molecular Mechanism of the TdpABC System

Core Components and Functional Relationships

The TdpABC system constitutes a minimal yet highly effective epigenetic defense system that combines DNA modification with targeted degradation of unmodified foreign DNA.

Table 1: Core Components of the TdpABC System

| Component | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| TdpC | DNA modification enzyme | Catalyzes phosphorothioate (PT) modification via adenylated intermediate; initiates "self" marking |

| TdpA | DNA translocase | Forms hexameric spiral staircase conformation; encircles duplex DNA; ATP-driven translocation |

| TdpB | Nuclease | Degrades PT-free phage DNA; provides defense against infection |

| Phosphorothioate (PT) Modification | Epigenetic "self" marker | Sulfur atom replaces non-bridging oxygen in DNA backbone; inhibits TdpAB activity on self-DNA |

The system operates through a highly coordinated mechanism where TdpC first marks cellular DNA with phosphorothioate modifications, creating a biochemical "self-identity" signature. When phage DNA enters the cell, the TdpAB complex recognizes the absence of these PT modifications and initiates degradation of the foreign genetic material [1] [32]. This elegant mechanism prevents autoimmune degradation of host DNA while providing effective defense against phage infection.

The Two-Step DNA Sulfuration Mechanism

The process of DNA phosphorothioation represents a novel biochemical pathway in prokaryotic epigenetics, occurring through two distinct enzymatic steps:

Activation Step: TdpC utilizes ATP to form an adenylated DNA intermediate, activating the DNA backbone for sulfur incorporation [1] [32].

Sulfur Substitution Step: The adenyl group is replaced with a sulfur atom, resulting in the final phosphorothioate modification that distinguishes self-DNA from non-self DNA [1] [32].

This adenylated intermediate represents a previously unknown mechanism in DNA phosphorothioation pathways and offers potential applications for synthetic biologists seeking to engineer novel DNA modification systems.

Structural Basis of Self vs. Non-Self Discrimination

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structural analysis of the TdpAB complex at 2.76 Å resolution has revealed the molecular details of its DNA recognition and discrimination capabilities [22] [7]. The TdpA hexamer binds one strand of encircled duplex DNA through hydrogen bonds arranged in a spiral staircase conformation [1] [32]. Crucially, the TdpAB-DNA interaction demonstrates exquisite sensitivity to the hydrophobicity of the PT sulfur, which inhibits ATP-driven translocation and nuclease activity on self-DNA [1] [32]. This structural autoinhibition mechanism prevents catastrophic autoimmune degradation while maintaining potent anti-phage activity.

Diagram 1: TdpABC System Mechanism - The two-step modification and defense pathway shows how host DNA is marked as "self" while unmarked phage DNA is targeted for degradation.

Experimental Characterization of TdpABC

Structural Biology Approaches

The molecular architecture of TdpABC has been elucidated through high-resolution structural techniques, primarily cryo-EM. The structural data available in the Protein Data Bank (accession 8WET) provides critical insights for engineering modified versions of the system [22] [7].

Table 2: Key Structural Features of TdpAB Complex

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 2.76 Å | Enables atomic-level understanding of DNA-protein interactions |

| TdpA Oligomerization | Hexameric | Forms spiral staircase conformation around DNA |

| DNA Binding | Single strand of encircled duplex | Explains translocation mechanism |

| PT-Sulfur Recognition | Hydrophobicity-sensitive | Molecular basis for self/non-self discrimination |

| Reconstruction Method | Single particle | State-of-the-art structural determination |

Functional Assays and Activity Measurements

Comprehensive functional characterization of TdpABC requires a multi-assay approach to quantify its modification, translocation, and nuclease activities:

DNA Phosphorothioation Quantification: Methods to detect and quantify PT modifications in genomic DNA, including mass spectrometry and specific biochemical assays [1].

Anti-phage Defense Assays: Plaque formation assays to measure protection efficiency against specific bacteriophages, providing direct evidence of defense capability [32].

Nuclease Activity Profiling: Gel electrophoresis and fluorescent-based assays to characterize TdpB nuclease activity and substrate specificity [1].

ATPase Activity Measurements: Kinetic assays to quantify ATP hydrolysis by TdpA, which drives DNA translocation [32].

Autoimmunity Prevention Validation: Experiments demonstrating that PT modifications inhibit TdpAB activity on self-DNA, confirming the system's self-tolerance mechanism [1].

Diagram 2: DBTL Cycle for TdpABC Engineering - The iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn framework adapted for engineering strains with enhanced phage resistance.

Implementation in Industrial Strain Engineering

Integration with Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Framework

Successful implementation of TdpABC in industrial strains requires systematic integration with the established DBTL cycle for strain engineering [31]:

Design Phase: Identify optimal integration sites in the industrial host genome, select appropriate regulatory elements for TdpABC expression, and design multiplexed strategies for stacking TdpABC with other defense systems.

Build Phase: Utilize CRISPR-based genome editing for precise integration of TdpABC cassettes, complemented by recombinase systems for larger DNA fragment insertion in challenging industrial hosts [31].

Test Phase: Implement high-throughput phenotyping to assess phage resistance, fitness costs, and production stability under simulated industrial conditions.

Learn Phase: Apply machine learning to multi-omics data to identify correlations between TdpABC expression levels, defense efficacy, and metabolic burden, informing subsequent engineering cycles [31].

Strategies for Industrial Application

Table 3: TdpABC Implementation Strategies for Different Biomanufacturing Scenarios

| Application Scenario | Implementation Approach | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| High-Value Molecule Production | Full TdpABC integration with strong constitutive promoters | Maximum phage protection for stable production of APIs and specialty chemicals |

| Bulk Chemical Production | TdpABC combined with other minimal defense systems | Balanced protection with minimal metabolic burden for competitive production |

| Extreme Condition Bioprocessing | TdpABC with native thermophile promoters | Enhanced robustness for high-temperature or specialized fermentation conditions |

| Multi-Strain Fermentations | Tuned TdpABC expression levels | Protection without cross-strain interference in co-culture systems |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for TdpABC Characterization and Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) [22] | Heterologous protein production for structural and biochemical studies |

| Structural Biology Tools | Cryo-EM grids, AMPPNP (ATP analog) [22] | Structural stabilization and determination of functional complexes |

| DNA Substrates | PT-modified DNA, unmodified phage DNA [1] | Functional assays for modification and degradation activities |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | Thermophilic cloning vectors, kanamycin/hygromycin resistance markers [32] | Genetic manipulation of thermophilic hosts and pathway engineering |

| Activity Assays | ATPase activity kits, nuclease detection reagents | Quantitative measurement of enzymatic functions |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The discovery and characterization of TdpABC represents a significant advancement in both fundamental understanding of prokaryotic defense systems and applied synthetic biology. The unique adenylated intermediate mechanism of DNA phosphorothioation [1] [32], combined with the sophisticated self/non-self discrimination capability of the TdpAB complex, provides synthetic biologists with a powerful new tool for enhancing biomanufacturing robustness. As industrial biotechnology continues to expand toward a projected $30 trillion global economic impact [31], such sophisticated defense systems will become increasingly critical for ensuring reliable, stable, and cost-effective bioproduction.

Future research directions should focus on expanding the toolkit of orthogonal TdpABC variants with different sequence specificities, engineering tunable expression systems for metabolic burden optimization, and developing high-throughput screening methods for rapid evaluation of system performance in industrial conditions. The integration of TdpABC with other defense mechanisms—creating layered protection systems—represents a particularly promising approach for comprehensive bioprocess protection. Through continued mechanistic investigation and creative engineering, TdpABC-based systems are poised to make significant contributions to the stability and productivity of next-generation industrial strains.