Strategic Search in Drug Discovery: Mastering the Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off in Chemical Space

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical balance between exploring novel regions of chemical space and exploiting known, promising areas.

Strategic Search in Drug Discovery: Mastering the Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off in Chemical Space

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical balance between exploring novel regions of chemical space and exploiting known, promising areas. We cover the foundational theory from multi-armed bandits to active learning, detail cutting-edge methodological implementations like Bayesian optimization and reinforcement learning, address common pitfalls and optimization strategies for real-world projects, and finally compare and validate different algorithmic approaches. The goal is to equip scientists with the strategic framework and practical tools to efficiently navigate the vast molecular landscape and accelerate the identification of viable drug candidates.

The Core Dilemma: Defining Exploration vs. Exploitation in Molecular Discovery

Technical Support Center

This support center is framed within the thesis on Balancing exploration and exploitation in chemical space search research. It addresses common practical issues encountered when navigating this vast theoretical landscape.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My virtual screening of a large library (1M+ compounds) is computationally intractable. How can I prioritize compounds for initial testing? A: This is a classic exploration-exploitation trade-off. Implement a multi-fidelity screening workflow.

- First Pass (Exploration): Use fast, low-cost filters (e.g., Rule of 5, PAINS filters, molecular weight) to remove undesirable compounds.

- Second Pass (Balanced): Apply medium-cost methods like 2D similarity searching or pharmacophore mapping to cluster compounds and select diverse representatives.

- Third Pass (Exploitation): Perform high-cost molecular docking or preliminary MD simulations on a focused subset (<10,000 compounds).

Q2: My synthesized lead compound shows poor solubility, halting further testing. How could this have been predicted and mitigated earlier? A: Solubility is a key dimension of chemical space often under-prioritized in exploration.

- Prevention: Integrate calculated physicochemical properties (e.g., LogP, LogS, polar surface area) as mandatory constraints in your virtual screening protocol.

- Mitigation: Employ a "property-focused" exploitation strategy. Create a focused library around your lead's core scaffold, systematically modifying substituents known to improve solubility (e.g., adding ionizable groups, reducing lipophilicity).

Q3: My high-throughput experimentation (HTE) results are noisy and irreproducible when exploring a new reaction space. What are the key checkpoints? A: Reproducibility is a critical practical constraint.

- Reagent Quality: Ensure solvents and reagents are dry and fresh, especially for air/moisture-sensitive chemistries. Use the "Research Reagent Solutions" table below.

- Liquid Handling Calibration: Regularly calibrate pipettes and liquid handlers. For nanoscale HTE, even minor deviations cause significant error.

- Control Density: Include positive and negative controls in every reaction plate to contextualize results and identify systematic failures.

Q4: How do I decide between exploring a new, uncharted chemical scaffold versus deeply optimizing a known hit series? A: This decision is the core of the research thesis. Implement a quantitative decision framework.

- Score the exploitation potential of your known hit (e.g., potency, synthetic accessibility, SAR understanding).

- Estimate the exploration potential of the new scaffold (e.g., novelty, structural diversity, predicted property space).

- Use a threshold or scoring matrix based on your project's risk tolerance and stage. Early discovery favors exploration; lead optimization demands exploitation.

Quantitative Data on Chemical Space

Table 1: Estimated Size of Chemical Space Segments

| Chemical Space Segment | Estimated Number of Compounds | Description/Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Potentially Drug-Like (GDB-17) | ~166 Billion | Molecules with up to 17 atoms of C, N, O, S, Halogens following simple chemical stability & drug-likeness rules. |

| Organic & Small Molecules | >10⁶⁰ | Theoretically possible following rules of valence. Vastly exceeds observable universe atoms. |

| Commercially Available | ~100 Million | Compounds readily purchasable from chemical suppliers (e.g., ZINC, Mcule databases). |

| Actually Synthesized | ~250 Million | Unique compounds reported in chemical literature (CAS Registry). |

Table 2: Key Dimensions & Practical Constraints in Navigation

| Dimension | Description | Typical Experimental Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Complexity | Molecular weight, stereocenters, ring systems. | Synthetic feasibility, cost, and time limit exploration of highly complex regions. |

| Physicochemical Property | LogP, solubility (LogS), pKa, polar surface area. | Must adhere to "drug-like" or "lead-like" boundaries for desired application. |

| Pharmacological Activity | Binding affinity, selectivity, functional efficacy. | Requires expensive, low-throughput in vitro or in vivo testing. |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Estimated ease and yield of synthesis. | The primary gatekeeper for moving from virtual to real compounds. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Fidelity Virtual Screening for Balanced Exploration-Exploitation Objective: To efficiently identify viable hit compounds from an ultra-large virtual library. Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Curate library (e.g., from ZINC). Standardize structures, remove duplicates, calculate 1D/2D descriptors.

- Tier 1 - Fast Filtering (Exploration Widening): Apply hard filters: 150 ≤ MW ≤ 600, -2 ≤ LogP ≤ 5, Rotatable Bonds ≤ 10. Remove PAINS and toxicophores.

- Tier 2 - Similarity & Diversity Selection (Balanced): For the remaining pool, calculate ECFP4 fingerprints. Perform k-means clustering. Select a diverse subset (e.g., 50,000 compounds) by choosing top N compounds closest to each cluster centroid.

- Tier 3 - High-Fidelity Docking (Exploitation Deepening): Prepare protein structure (e.g., from PDB). Define binding site. Dock the 50,000-compound subset using Glide SP or AutoDock Vina. Select top 1,000 by docking score for visual inspection and further analysis.

Protocol 2: Focused Library Synthesis for SAR Exploitation Objective: To optimize a lead compound's potency through systematic analog synthesis. Methodology:

- SAR Analysis: Identify the core scaffold and variable R-groups (R1, R2, R3) of the lead.

- Library Design: For each R-group position, select 5-10 substituents representing a range of properties (e.g., electron-donating/withdrawing, small/large, polar/apolar).

- Parallel Synthesis: Employ a parallel synthesis technique (e.g., automated microwave synthesis, solid-phase synthesis) to combinatorially generate the analog library (e.g., 5 x 5 x 5 = 125 compounds).

- Purification & Characterization: Purify all compounds via automated flash chromatography. Characterize using LC-MS and NMR.

- Biological Testing: Test all analogs in a consistent in vitro assay (e.g., enzyme inhibition IC₅₀). Plot results in a matrix to visualize SAR.

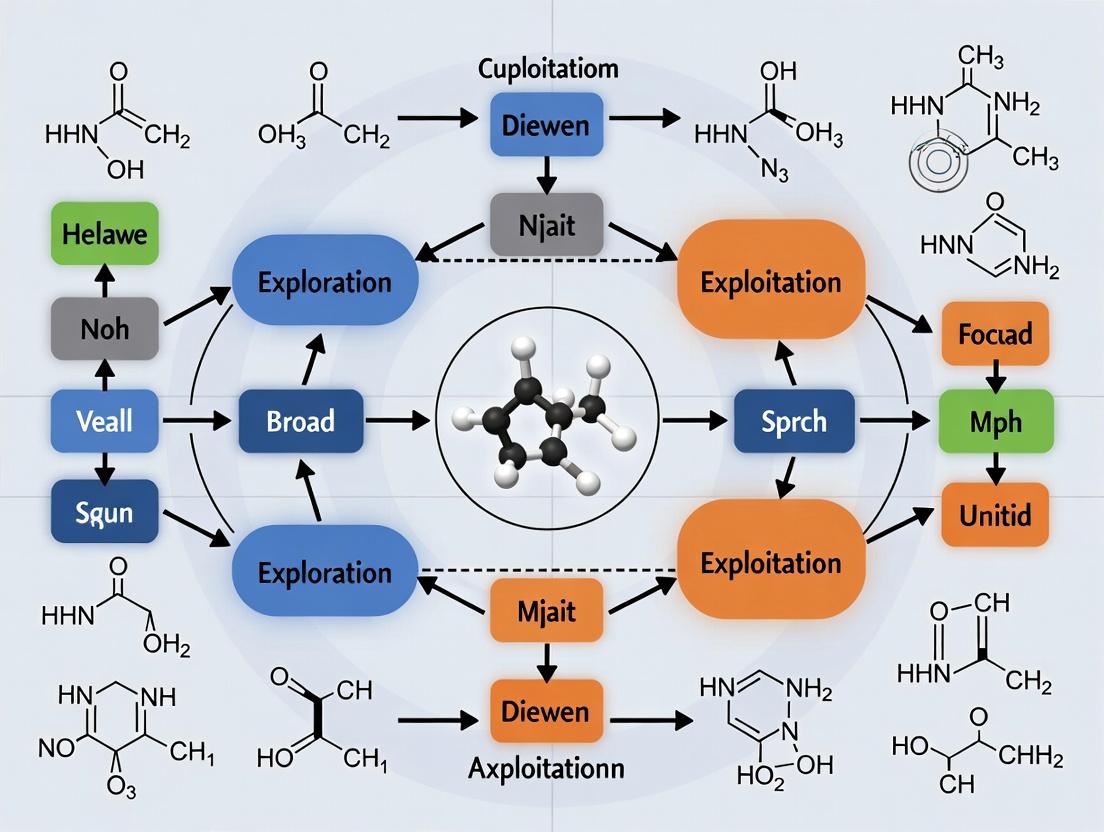

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Title: Multi-Fidelity Virtual Screening Workflow

Title: Exploration-Exploitation Decision Logic in Chemical Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Reproducible High-Throughput Experimentation

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Anhydrous Solvents (DMSO, DMF, THF) | High-purity, dry solvents prevent unwanted side reactions and catalyst deactivation, crucial for reproducibility in screening. |

| Deuterated Solvents for Reaction Monitoring | Enables real-time, in-situ NMR tracking of reactions in HTE plates, providing mechanistic insight. |

| Solid-Supported Reagents & Scavengers | Simplify purification in parallel synthesis; allows for filtration-based workup, enabling automation. |

| Pre-weighed, Sealed Reagent Kits | Ensures consistent stoichiometry and eliminates weighing errors for air/moisture-sensitive compounds in HTE. |

| Internal Standard (for LC-MS/GC-MS) | A consistent compound added to all analysis samples to calibrate instrument response and quantify yields reliably. |

| Positive/Negative Control Compounds | Benchmarks for biological or catalytic activity in every assay plate, essential for data normalization and identifying false results. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During a virtual screening campaign using a multi-armed bandit (MAB) algorithm, my agent gets stuck exploiting a single, sub-optimal compound series too early. How can I encourage more sustained exploration?

A: This is a classic issue of insufficient exploration. Implement or adjust the following:

- Epsilon-Greedy Adjustment: Systematically decay the exploration rate (ε) over time instead of using a fixed value. Start with a high ε (e.g., 0.3) and reduce it according to a schedule (e.g., εt = ε0 / log(t+1)).

- Switch to Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Adopt UCB1 or its variants. UCB explicitly balances the estimated reward (exploitation) and the uncertainty (exploration) for each "arm" (compound series). The formula for arm i at round t is:

UCB(i, t) = μ_i + √(2 * ln(t) / n_i), whereμ_iis the average observed reward andn_iis the number of times arm i has been pulled. - Contextual Bandits: If you have molecular descriptors (context), use a Linear UCB or Thompson Sampling with a linear model. This allows for generalization across chemical space, making exploration more intelligent.

Q2: How do I define a meaningful and computationally efficient "reward" for a bandit algorithm in a drug discovery setting?

A: The reward function is critical. It must be a proxy for the ultimate goal (e.g., binding affinity, solubility) and cheap to evaluate. Common strategies include:

- Proxy Models: Use predictions from a fast, pre-trained machine learning model (e.g., a Random Forest or a shallow Neural Network predicting pIC50) as the reward.

- Multi-Fidelity Rewards: Implement a tiered reward system. Initial rewards come from cheap calculations (e.g., docking score, QSAR prediction). Only compounds that pass a reward threshold are evaluated with more expensive methods (e.g., MM/GBSA, experimental assay), updating the reward for that arm with the higher-fidelity data.

- Shaped Rewards: Incorporate penalties for undesirable properties (e.g., high molecular weight, poor solubility) directly into the reward calculation:

Reward = Docking_Score - λ * (MW_penalty + SA_penalty).

Table 1: Comparison of Reward Strategies

| Strategy | Computational Cost | Data Efficiency | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Experimental | Very High | Low | Late-stage, small libraries |

| Proxy ML Model | Low | High | Large virtual libraries |

| Multi-Fidelity | Medium | Medium | Iterative screening campaigns |

| Shaped Reward | Low-Medium | High | Early-stage property optimization |

Q3: My Thompson Sampling agent for molecule optimization seems to converge to a local optimum. What diagnostics can I run?

A: Perform the following diagnostic checks:

- Posterior Visualization: Plot the posterior distributions (e.g., Gaussian for each arm) over time. If they separate and collapse too quickly, exploration is insufficient.

- Arm Selection Statistics: Track the percentage of rounds each compound series (arm) is selected. A healthy run should show a gradual focus, not an abrupt shift to one arm.

- Regret Analysis: Calculate the cumulative regret: the difference between the reward of the optimal arm (in hindsight) and the reward obtained. Plot cumulative regret over rounds. Linear regret indicates poor performance; sublinear (logarithmic) regret is ideal.

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Regret

- Pre-run: Identify the best possible compound series (arm) using a full enumeration of your library (if possible) or a prior benchmark.

- Define Optimal Reward: Set the expected reward of this optimal arm as

μ*. - Log Data: During the MAB run, log the reward

r_treceived at each roundt. - Calculate Instantaneous Regret:

δ_t = μ* - r_t. - Calculate Cumulative Regret:

R_T = Σ_{t=1 to T} δ_t. - Plot: Generate a line plot of

R_Tvs.T. Compare the curve's growth rate to theoretical bounds (log(T)).

Q4: How do I map a chemical space search problem onto a multi-armed bandit formalism?

A: Follow this structured mapping protocol:

Experimental Protocol: Problem Formulation for Chemical Bandits

- Define Arms: Cluster your compound library into discrete series or "buckets" based on scaffold or key functional groups. Each cluster is an arm. Alternatively, define each arm as a specific reaction or transformation in a synthesis plan.

- Define Context (If Contextual): Compute a feature vector (e.g., ECFP6 fingerprint, RDKit descriptors) for each individual compound. This is the context

x. - Initialize Reward Model: Choose a prior for each arm. For Bernoulli bandits (success/failure), use a Beta(α=1, β=1) prior. For Gaussian rewards, use a Normal-Gamma prior.

- Select Arm: At each iteration

t, use your chosen policy (ε-Greedy, UCB, Thompson Sampling) to select an arma_t. - Sample & Evaluate: If using contextual bandits, sample a specific compound from the chosen arm's cluster, perhaps based on its context. Obtain its reward

r_t(e.g., assay result, prediction score). - Update Model: Update the posterior distribution or the average reward estimate for the selected arm

a_twith the new observation(x_t, r_t). - Loop: Repeat steps 4-6 until the budget (e.g., number of experiments) is exhausted.

Chemical Space MAB Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for a Multi-Armed Bandit Experiment in Chemical Search

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Discretized Chemical Library | Pre-clustered compound sets (by scaffold, Bemis-Murcko framework) serving as the foundational "arms" for classical bandits. |

| Molecular Featurization Software (e.g., RDKit, Mordred) | Generates numerical context vectors (descriptors, fingerprints) for contextual bandit approaches. |

| Proxy/Predictive Model | A fast, pre-trained QSAR/activity model to provide cheap, initial reward estimates for guiding exploration. |

| Bandit Algorithm Library (e.g., Vowpal Wabbit, MABWiser, custom Python) | Core engine implementing selection policies (UCB, Thompson Sampling) and maintaining reward estimates. |

| Multi-Fidelity Data Pipeline | A system to integrate low-cost (docking, prediction), medium-cost (MD simulation), and high-cost (experimental) reward data, updating arm estimates accordingly. |

| Regret & Convergence Monitor | Diagnostic dashboard tracking cumulative regret, arm selection counts, and posterior distributions to ensure balanced search. |

MAB Agent-Environment Interaction

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Search Strategy in Chemical Space

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does 'regret' quantify in a chemical space search, and how is it calculated? A1: In this context, regret quantifies the opportunity cost of not selecting the optimal compound (e.g., highest binding affinity, desired property) at each iteration of a search campaign. Cumulative regret is the sum of these differences over time. Low cumulative regret indicates an effective strategy balancing exploration and exploitation.

Formula: Instantaneous Regret = (Performance of Best Possible Compound) - (Performance of Compound Selected at time t). Cumulative Regret = Σ (Instantaneous Regret over T rounds).

Q2: My search is getting stuck in a local optimum. How can I adjust my algorithm parameters to encourage more exploration? A2: This is a classic sign of over-exploitation. Adjust the following parameters in your acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Thompson Sampling):

- Increase the exploration weight (β) in UCB: A higher β value prioritizes uncertainty, directing the search to less sampled regions of chemical space.

- For ε-Greedy strategies, increase ε: This raises the probability of choosing a random compound for evaluation.

- Review your kernel's length scales: In Gaussian Process-based Bayesian Optimization, shorter length scales can lead to more localized exploitation. Consider lengthening them to allow the model to generalize across broader regions.

Q3: How do I decide when to stop a sequential search experiment? A3: Stopping is recommended when the marginal cost of a new experiment outweighs the expected reduction in regret. Monitor these metrics:

- Plateau in Performance: No significant improvement in primary objective (e.g., pIC50) over the last N iterations (e.g., 20-30).

- Diminishing Regret Reduction: The rate of decrease in cumulative regret approaches zero.

- Budget Exhaustion: Pre-defined budget (number of compounds, computational time, lab resources) is consumed.

Q4: My surrogate model predictions are poor, leading to high regret. How can I improve model accuracy? A4: Poor model fidelity undermines the entire search. Troubleshoot using this checklist:

- Feature Representation: Ensure your molecular featurization (e.g., fingerprints, descriptors, graphs) captures relevant chemical information for the property of interest.

- Initial Dataset Size: The surrogate model requires a sufficiently diverse initial dataset (e.g., 50-100 compounds) for meaningful learning. Consider augmenting with publicly available data.

- Model Choice: Evaluate if your model (Random Forest, Gaussian Process, Graph Neural Network) is appropriate for the data structure and size. Cross-validate rigorously.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Initial Cumulative Regret in Early Search Rounds Diagnosis: This is often due to an uninformed or poorly diversified initial set of compounds (the "seed set"). Resolution Protocol:

- Step 1: Characterize the diversity of your seed set using Tanimoto similarity or principal component analysis (PCA) of molecular descriptors.

- Step 2: If diversity is low (<0.7 average pairwise dissimilarity), employ a space-filling design (e.g., Kennard-Stone, Latin Hypercube Sampling) on chemical descriptors to select a new, more representative seed set.

- Step 3: Re-initiate the search with the new seed set and monitor regret trajectory.

Issue: Volatile Regret with High Variance Between Iterations Diagnosis: The acquisition function may be overly sensitive to model noise or the experimental noise (assay variability) is high. Resolution Protocol:

- Step 1 (Assay Check): Re-test previous high-performing compounds to estimate experimental noise. Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV). If CV > 15%, prioritize assay optimization.

- Step 2 (Algorithm Tuning): For acquisition functions like Expected Improvement, add a jitter parameter or increase the xi parameter to dampen over-sensitive reactions to small prediction differences.

- Step 3: Implement batch selection (e.g., q-UCB, batch Thompson Sampling) to evaluate several compounds in parallel, which can smooth the regret curve.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Search Algorithm Performance on a Simulated Drug Likeness (QED) Optimization Scenario: Searching a 10,000 molecule library for max QED over 100 sequential queries.

| Algorithm | Cumulative Regret (↓) | Best QED Found (↑) | Exploitation Score* | Exploration Score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Search | 12.45 | 0.948 | 0.10 | 0.95 |

| ε-Greedy (ε=0.1) | 8.91 | 0.949 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| Bayesian Opt. (UCB, β=0.3) | 5.23 | 0.951 | 0.82 | 0.18 |

| Pure Exploitation (Greedy) | 15.67 | 0.923 | 0.98 | 0.02 |

(Scores normalized from 0-1 based on selection analysis.)*

Table 2: Key Parameters for Common Regret-Minimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Tunable Parameter | Effect of Increasing Parameter | Typical Starting Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ε-Greedy | ε (epsilon) | Increases random exploration. | 0.05 - 0.1 |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | β (beta) | Increases optimism/exploration of uncertain regions. | 0.1 - 0.5 |

| Thompson Sampling | Prior Distribution Variance | Increases initial exploration spread. | Informed by data. |

| Gaussian Process BO | Kernel Length Scale | Longer scales smooth predictions, encouraging global search. | Automated Relevance Determination (ARD). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Search Strategy Using Cumulative Regret Objective: Quantitatively compare the performance of two search algorithms (e.g., Random Forest UCB vs. Thompson Sampling) for a molecular property prediction task. Materials: Pre-computed molecular descriptor database, property values for full dataset (ground truth), computing cluster. Methodology:

- Initialization: Randomly select a seed set of 50 molecules from the full database. Hide the remaining property values.

- Iterative Search Loop (for each algorithm, independently): a. Train a surrogate model (Random Forest) on all currently evaluated molecules (descriptors -> property). b. Use the algorithm's acquisition function to select the next 1 molecule from the unevaluated pool. c. "Query" the ground truth for that molecule's property. d. Calculate instantaneous regret: (Max global property) - (Property of selected molecule). e. Add molecule and its property to the training set.

- Repeat Step 2 for 200 iterations.

- Analysis: Plot cumulative regret vs. iteration for both algorithms. The algorithm with the lower area under the cumulative regret curve is superior for this task.

Protocol 2: Calibrating Exploration Weight (β) in UCB for a New Chemical Series Objective: Empirically determine an optimal β value for a real-world high-throughput screening (HTS) follow-up campaign. Materials: Primary HTS hit list (≥ 1000 compounds), secondary assay ready for sequential testing. Methodology:

- Setup: Featurize all compounds. Use the top 20 hits by primary assay potency as the initial seed set.

- Parallel Tracks: Run three identical Bayesian Optimization workflows in parallel, differing only in the UCB β parameter: Low (0.1), Medium (0.3), High (0.7).

- Weekly Cycle: Each week, each workflow proposes a batch of 5 compounds for testing based on its model and β.

- Evaluation: After 10 weeks (50 compounds tested per track), analyze:

- Cumulative potency gain.

- Diversity of selected compounds (average pairwise similarity).

- Number of distinct molecular scaffolds discovered.

- Selection: Choose the β value whose track best balances finding the most potent compound (exploitation) and discovering new productive scaffolds (exploration).

Visualizations

Diagram 1: The Regret Minimization Search Cycle

Diagram 2: Exploration vs. Exploitation in Chemical Space

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function & Role in Regret Minimization |

|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Software (e.g., RDKit, Dragon) | Generates quantitative numerical features from chemical structures, forming the fundamental representation of "chemical space" for the surrogate model. |

| Surrogate Model Library (e.g., scikit-learn, GPyTorch) | Provides algorithms (Random Forest, Gaussian Process, Neural Networks) to learn the structure-property relationship from available data and predict uncertainty. |

| Acquisition Function Code | Implements the decision rule (UCB, EI, Thompson Sampling) that quantifies the "value" of testing each unexplored compound, balancing predicted performance vs. uncertainty. |

| Assay-Ready Compound Library | The physical or virtual set of molecules to be searched. Quality (diversity, purity) directly impacts the achievable minimum regret. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay | The "oracle" that provides expensive, noisy ground-truth data for selected compounds. Its precision and accuracy are critical for valid regret calculation. |

| Laboratory Automation (Liquid handlers, plate readers) | Enforces the sequential experimental protocol with high reproducibility, minimizing technical noise that could distort the regret signal. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: General Concepts

Q1: What are the key metrics used to quantify exploration and exploitation in a chemical space search? A1: The balance is measured using specific, complementary metrics. Table 1: Key Metrics for Balancing Exploration and Exploitation

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Measures | Typical Target/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploitation (Performance) | Predicted Activity (e.g., pIC50, Ki) | Binding affinity or potency of designed molecules. | Higher is better. |

| Drug-likeness (e.g., QED) | Overall quality of a molecule as a potential oral drug. | Closer to 1.0 is better. | |

| Synthetic Accessibility Score (SA) | Ease of synthesizing the molecule. | Lower is better (e.g., 1-10 scale, 1=easy). | |

| Exploration (Novelty) | Molecular Similarity (e.g., Tanimoto to training set) | Structural novelty compared to a known set. | Lower similarity indicates higher novelty. |

| Scaffold Novelty | Percentage of molecules with new Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. | Higher percentage indicates broader exploration. | |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Diversity of molecules in a defined descriptor space (e.g., PCA). | Broader distribution is better. |

Q2: My model is stuck generating very similar, high-scoring molecules. How can I force more exploration? A2: This is a classic over-exploitation issue. Adjust the following algorithmic parameters:

- Increase the "Temperature" (τ) parameter: In probabilistic models (e.g., RL, generative models), a higher temperature increases randomness, making low-probability (novel) selections more likely.

- Adjust the Acquisition Function: If using Bayesian Optimization, switch from pure expected improvement (EI) to upper confidence bound (UCB) or add an explicit distance penalization term to favor points far from previously sampled ones.

- Diversify the Starting Population: In genetic algorithms, ensure the initial population is highly diverse. Introduce random mutations at a higher rate.

Q3: My search is generating highly novel but poor-performing molecules. How can I refocus on quality? A3: This indicates excessive exploration. Apply these corrective measures:

- Increase Exploitation Weighting: Recalibrate your objective function. Increase the weight or penalty associated with critical performance metrics (e.g., predicted activity, SA score).

- Implement a Performance Filter: Introduce a hard threshold in your workflow (e.g., "only explore molecules with predicted pIC50 > 7.0").

- Lower the "Temperature" (τ) parameter: This makes the model more deterministic, favoring high-probability, known-good solutions.

- Utilize a Memory/Experience Replay Buffer: Retain and periodically resample high-performing molecules from earlier stages to reinforce their characteristics.

FAQ: Technical Implementation

Q4: How do I technically implement a reward function for Reinforcement Learning (RL) that balances novelty and performance?

A4: A common approach is a multi-component reward function:

R(molecule) = w1 * Activity_Score + w2 * SA_Penalty + w3 * Novelty_Bonus

- Activity_Score: Normalized predicted bioactivity.

- SA_Penalty: Negative reward for high synthetic accessibility scores.

- Novelty_Bonus: Reward based on inverse Tanimoto similarity to a reference set.

- w1, w2, w3: Tunable weights that control the balance. Start with w1=1.0, w2=-0.5, w3=0.2 and adjust based on output.

Q5: In a Bayesian Optimization (BO) loop, the model suggests molecules that are invalid or cannot be synthesized. How do I fix this? A5: Constrain your search space.

- Pre-processing Constraint: Use a rules-based filter (e.g., medicinal chemistry filters, PAINS filters) before the proposal is evaluated by the surrogate model.

- Latent Space Constraint: If using a variational autoencoder (VAE), ensure the decoder only produces valid molecules by training on a corpus of synthetically accessible compounds.

- Post-processing Correction: Implement a validity checker and "corrector" step. If the BO proposes an invalid SMILES, it can be passed through a repair algorithm before being added to the training set.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Multi-Objective Optimization Experiment

Objective: To generate a Pareto front of molecules balancing predicted activity (pIC50) and scaffold novelty.

- Define Objectives: Set Objective A: Maximize predicted pIC50 (from a QSAR model). Set Objective B: Maximize minimum Tanimoto distance (1 - similarity) to the training set molecules.

- Choose Algorithm: Select a multi-objective algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II, MOEA/D) integrated with a molecular generator (e.g., graph-based GA, SMILES-based RL).

- Initialization: Create a random, diverse population of 100 molecules from your seed set.

- Evaluation: For each molecule in the population, compute Objective A and Objective B.

- Iteration: Run the algorithm for 50 generations. The algorithm will select, crossover, and mutate molecules to evolve the population.

- Analysis: Extract the non-dominated front (Pareto front) from the final generation. These molecules represent the optimal trade-offs between activity and novelty.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Exploration vs. Exploitation Trade-off in a Campaign

Objective: Quantify the progression of novelty and performance over an active learning cycle.

- Setup: Run a standard Bayesian Optimization loop for 50 iterations, aiming to maximize pIC50.

- Log Data: At every 5th iteration, record:

- Average pIC50 of the proposed batch (Exploitation)

- Average Tanimoto similarity of the batch to the initial training set (Exploration: lower similarity = higher novelty)

- Visualization: Plot iteration number vs. (a) Average pIC50 and (b) Average Similarity on a dual-axis chart.

- Interpretation: An effective balanced search should show a general upward trend in pIC50 while maintaining or only gradually increasing the average similarity, indicating sustained novelty.

Diagrams

Active Learning Loop for Multi-Objective Search

RL Reward Function Balancing Act

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Exploration-Exploitation Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in Experiment | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR/Predictive Model | Software/Model | Provides the primary exploitation metric (e.g., predicted activity, solubility). Crucial for virtual screening. | Random Forest, GNN, commercial platforms (Schrodinger, MOE). |

| Molecular Generator | Software/Algorithm | Core engine for proposing new chemical structures. Design determines exploration capacity. | SMILES-based RNN/Transformer, Graph-Based GA, JT-VAE. |

| Diversity Selection Algorithm | Software/Algorithm | Actively promotes exploration by selecting dissimilar molecules from a set. | MaxMin algorithm, sphere exclusion, k-means clustering. |

| Bayesian Optimization Suite | Software Framework | Manages the iterative propose-evaluate-update loop, balancing exploration/exploitation via acquisition functions. | Google Vizier, BoTorch, Scikit-Optimize. |

| Chemical Space Visualization Tool | Software | Maps generated molecules to assess coverage and identify unexplored regions (exploration audit). | t-SNE, UMAP plots based on molecular descriptors/fingerprints. |

| Synthetic Accessibility Scorer | Software/Model | Penalizes unrealistic molecules, grounding exploitation in practical chemistry. | SA Score (RDKit), SYBA, RAscore. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Data | Dataset | Serves as the initial training set and reality check for exploitation metrics. | PubChem BioAssay, ChEMBL. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our Bayesian optimization algorithm for reaction yield prediction is exploiting known high-yield conditions too aggressively and failing to explore new, promising regions of chemical space. How can we adjust our priors to better balance this? A: This indicates your prior on catalyst performance may be too "sharp" or overconfident. Implement a tempered or "flattened" prior distribution. For example, if using a log-normal prior for yield based on historical data, increase the variance parameter. A practical protocol:

- Re-analyze your historical yield dataset (e.g., past 100 similar reactions).

- Calculate the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of log(yield).

- For the new search, set your prior mean to μ but inflate the standard deviation to kσ, where k is a tuning parameter (start with k=1.5).

- This wider, less confident prior encourages the acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to value unexplored conditions more highly.

Q2: When using a Gaussian Process (GP) to model solubility, how do I encode the prior knowledge that adding certain hydrophobic groups beyond a threshold always decreases aqueous solubility? A: You can incorporate this as a monotonicity constraint in the GP prior. Instead of a standard squared-exponential kernel, use a kernel that enforces partial monotonicity. Experimental Protocol for Constrained GP:

- Kernel Selection: Use a Gibbs kernel or a kernel from the

GPyTorchlibrary that supports monotonicity constraints. - Define Constraint Regions: In your feature space (e.g., molecular descriptor for hydrophobicity), specify the dimension(s) and direction (decreasing) for the constraint.

- Virtual Observations: Add synthetic data points that explicitly satisfy the monotonic rule to your training set, but with a very small noise parameter to ensure they act as "soft" constraints rather than hard data.

- Model Validation: Test the model's predictions on a held-out set of known compounds to ensure the monotonic trend holds without degrading overall predictive accuracy.

Q3: We are screening a new library of fragments. Our historical hit rates for similar libraries are ~5%. How should we use this 5% as a prior in our multi-armed bandit active learning protocol? A: Use a Beta prior in a Bayesian Bernoulli model for each fragment's probability of being a hit. Methodology:

- Interpret the historical 5% hit rate (e.g., 50 hits out of 1000 compounds) as a Beta(α=50, β=950) prior distribution.

- For each new fragment i in the current screen, start with this prior: Hit Probability ~ Beta(α⁰ᵢ=50, β⁰ᵢ=950).

- As you test fragments and get binary outcomes (hit=1, miss=0), update the posterior: Beta(α⁰ᵢ + successes, β⁰ᵢ + failures).

- Your acquisition function (e.g., Thompson Sampling) should draw samples from these posteriors to decide which fragment to test next. This naturally balances exploring fragments with high uncertainty and exploiting those with high expected hit probability.

Table 1: Impact of Prior Strength on Search Performance in a Simulated Drug Discovery Benchmark

| Prior Type | Historical Data Points Used | Average Final Yield/Activity (%) | Average Steps to Find Optimum | Exploration Metric (Avg. Distance Traveled in Descriptor Space) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninformed (Uniform Prior) | 0 | 78.2 | 42 | 15.7 |

| "Weak" Informed Prior (Broad Dist.) | 50 | 88.5 | 28 | 9.4 |

| "Strong" Informed Prior (Sharp Dist.) | 200 | 92.1 | 18 | 4.2 |

| Overconfident Misppecified Prior | 50 (from different dataset) | 75.8 | 35 | 6.1 |

Table 2: Comparison of Bayesian Optimization Methods with Different Priors for Catalyst Selection

| Method | Prior Component | Avg. Improvement Over Random Search (%) | Computational Overhead (Relative Time) | Robustness to Prior Mismatch (Score 1-10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard GP (EI) | None / Uninformative | 220 | 1.0x (Baseline) | 10 |

| GP with Historical Mean Prior | Linear Mean Function | 285 | 1.1x | 7 |

| GP with Domain-Knowledge Kernel | Custom Composite Kernel | 310 | 1.3x | 5 |

| Hierarchical Bayesian Model | Empirical Bayes Hyperpriors | 295 | 1.8x | 8 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calibrating Priors for a New Chemical Space Objective: Systematically set prior parameters when moving from one project domain (e.g., kinase inhibitors) to another (e.g., GPCR ligands).

- Data Collation: Gather all historical dose-response data (pIC50) from the source domain (Kinases). Calculate mean (μsrc) and variance (σ²src) of the log-transformed values.

- Expert Elicitation: With domain scientists, define a "similarity score" (S, 0-1) between the source and target (GPCR) domains based on molecular properties and assay conditions.

- Prior Transfer: Set the prior for the target domain as a Normal distribution: μtgt = μsrc, σ²tgt = σ²src / S. A low similarity (S→0) inflates variance, creating a less informative prior.

- Validation Loop: Run a short pilot screen of 50 compounds in the new domain. Update the prior to a posterior using Bayesian updating. Compare the posterior mean to the pilot's empirical mean to assess prior calibration.

Protocol: Building a Knowledge-Based Kernel for Reaction Outcome Prediction Objective: Integrate domain knowledge about functional group compatibility into a GP kernel.

- Feature Engineering: Represent each reaction by (a) computed molecular descriptors of reactants, and (b) a binary vector indicating the presence/absence of key functional groups (e.g., -OH, -NH2, -Br).

- Kernel Design: Construct a composite kernel:

K_total = w1 * K_RBF(descriptors) + w2 * K_Jaccard(binary_vector). The RBF kernel captures smooth similarity, the Jaccard kernel captures exact functional group matches. - Prior on Weights (w1, w2): Set a Dirichlet prior favoring the knowledge-based kernel (w2) if the historical database shows strong functional group determinism. For example, Dirichlet(α=[1, 3]).

- Model Fitting: Infer the kernel weights along with other GP hyperparameters using type-II maximum likelihood or MCMC, allowing the data to refine the strength of the domain-knowledge prior.

Visualizations

Title: Bayesian Optimization Loop with Priors

Title: Composite Kernel Structure for Priors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Function & Role in Leveraging Priors |

|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Software (e.g., BoTorch, GPyOpt) | Provides the framework to implement custom priors, kernels, and acquisition functions for chemical space search. |

| Cheminformatics Library (e.g., RDKit) | Generates molecular descriptors and fingerprints that form the feature basis for knowledge-informed prior kernels. |

| Historical HTS/HCS Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, corporate DB) | The primary source of quantitative data for constructing empirical prior distributions on compound activity. |

| Probabilistic Programming Language (e.g., Pyro, Stan) | Allows for flexible specification of complex hierarchical priors that combine multiple data sources and expert beliefs. |

| Domain-Specific Ontologies (e.g., RXNO, Gene Ontology) | Provides a structured vocabulary to codify expert knowledge into computable constraints for priors. |

| Automated Liquid Handling & Reaction Rigs | Enables the high-throughput experimental testing required to rapidly validate and update priors in an active learning loop. |

From Theory to Lab: Modern Algorithms for Navigating Chemical Space

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithm converging to a suboptimal region of chemical space?

- Answer: This is often a sign of an imbalanced acquisition function. The standard Expected Improvement (EI) can become too exploitative. In the context of chemical space search, where the landscape is vast and rugged, this leads to premature convergence. To remedy this, increase the exploration parameter (kappa for Upper Confidence Bound) or use a decay schedule for kappa. Alternatively, switch to a more exploratory acquisition function like Probability of Improvement (PI) with a small, non-zero trade-off parameter or investigate information-theoretic acquisitions like Entropy Search.

FAQ 2: My surrogate model (Gaussian Process) is taking too long to train as my dataset of evaluated molecules grows. How can I scale BO for high-throughput virtual screening?

- Answer: Gaussian Process (GP) regression scales cubically (O(n³)) with the number of data points. For scaling in chemical search:

- Use Sparse Gaussian Process Models: Implement approximations using inducing points to reduce computational complexity.

- Switch to Tree-Structured Parzen Estimators (TPE): TPE is often more efficient for very high-dimensional, categorical-like molecular representations (e.g., SMILES strings) in early search phases.

- Batch Bayesian Optimization: Use q-EI or local penalization methods to select a batch of molecules for parallel experimental evaluation (e.g., in parallel assay plates).

- Feature Dimensionality Reduction: Apply techniques like PCA or autoencoders to your molecular fingerprint/descriptor space before training the GP.

FAQ 3: How do I effectively encode categorical variables (like functional group presence) and continuous variables (like concentration) simultaneously in a BO run for chemical reaction optimization?

- Answer: Use a hybrid kernel in your Gaussian Process. A common and effective approach is to use a combination of a continuous kernel (like Matérn) for continuous variables and a discrete kernel (like Hamming) for categorical variables. For example, in a reaction optimizing temperature, catalyst amount, and solvent type, define a kernel as:

K_total = K_Matérn(temperature) * K_Matérn(catalyst) + K_Hamming(solvent).

FAQ 4: The performance of my BO-driven search plateaus after an initial period of rapid improvement. Is the algorithm stuck?

- Answer: A plateau may indicate that the algorithm has exhausted local improvements and needs a strategic nudge for exploration. Implement a "restart" protocol:

- Trigger: Monitor improvement over the last N iterations (e.g., 20). If the best observed value hasn't changed beyond a threshold ε, trigger a restart.

- Action: Re-initialize the surrogate model by adding random exploration points to the dataset, or temporarily switch the acquisition function to pure random search for 2-5 iterations to diversify the data.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Acquisition Functions in Molecular Property Optimization

Objective: Compare EI, UCB, and PI for optimizing the penalized logP score of a molecule using a SELFIES representation.

- Representation: Encode the initial molecular set (e.g., from ZINC database) as SELFIES strings.

- Surrogate Model: Use a GP with a composite kernel (string kernel for SELFIES + Tanimoto kernel for Morgan fingerprints).

- Acquisition Functions: Run three parallel BO loops (50 iterations each, 5 initial random points), each using EI, UCB (κ=2.576), or PI (ξ=0.01).

- Evaluation: Use the RDKit-based scoring function to compute the penalized logP for each proposed molecule.

- Analysis: Record the best-found score per iteration. Repeat 10 times with different random seeds.

Table 1: Performance of Acquisition Functions after 50 Iterations (Mean ± Std)

| Acquisition Function | Best Penalized logP Score | Convergence Iteration | Avg. Runtime per Iteration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | 4.21 ± 0.85 | 32 ± 7 | 45.2 ± 5.1 |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB, κ=2.576) | 5.87 ± 1.12 | 41 ± 9 | 46.8 ± 4.7 |

| Probability of Improvement (PI, ξ=0.01) | 3.45 ± 0.92 | 28 ± 5 | 44.9 ± 5.3 |

Protocol 2: Implementing a Batch BO Loop for Parallel Screening

Objective: Select a batch of 6 candidate molecules for parallel synthesis and assay using the q-Expected Improvement method.

- Initial Data: Start with a dataset of 50 molecules with known IC50 values from a preliminary screen.

- Model Training: Fit a GP model using 1024-bit Morgan fingerprints (radius=2) as input and -log(IC50) as the target.

- Batch Selection: Using the fitted GP, optimize the q-EI acquisition function (with q=6) via gradient-based methods to propose the 6 molecules expected to collectively yield the highest improvement.

- Parallel Evaluation: Send the 6 molecular structures for parallel synthesis and biological testing.

- Update & Iterate: Incorporate the new 6 data points into the training set and repeat from Step 2.

Visualization: BO Workflow in Chemical Search

Title: Bayesian Optimization Loop for Drug Discovery

Title: Exploration-Exploitation Balance in BO

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Tools for BO-Driven Chemical Research

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Software Library | Core engine for building the surrogate model that predicts chemical properties and their uncertainty. | GPyTorch, scikit-learn, GPflow |

| Molecular Representation Library | Converts chemical structures into machine-readable formats (vectors/graphs). | RDKit (for fingerprints, descriptors), DeepChem |

| Acquisition Function Optimizer | Solves the inner optimization problem to propose the next experiment. | BoTorch (for Monte Carlo-based optimization), scipy.optimize |

| High-Throughput Assay Kits | Enables parallel experimental evaluation of batch BO candidates. | Enzymatic activity assay kits (e.g., from Cayman Chemical), cell viability kits. |

| Chemical Space Database | Provides initial seed compounds and a broad view of synthesizable space. | ZINC, ChEMBL, Enamine REAL. |

| Automation & Lab Informatics | Tracks experiments, links computational proposals to lab results, and manages data flow. | Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN), Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS). |

Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Policy-Gradient Methods for de novo Design

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During RL training for molecular generation, my agent's reward plateaus early, and it gets stuck generating a small set of similar, suboptimal structures. How can I improve exploration? A1: This is a classic exploitation-over-exploration problem. Implement or adjust the following:

- Entropy Regularization: Increase the

entropy_coefficient(e.g., from 0.01 to 0.05) in your PPO or REINFORCE loss function to encourage action diversity. - Intrinsic Reward: Add a novelty bonus. Use a running fingerprint (e.g., ECFP4) dictionary; reward the agent for generating structures with Tanimoto similarity below a threshold (e.g., <0.4) to existing ones.

- Epsilon-Greedy Sampling: During training, with probability ε (start at 0.3, decay to 0.05), select a random valid action from the vocabulary instead of the top policy action.

Q2: My policy gradient variance is high, leading to unstable and non-convergent training. What are the key stabilization steps? A2: Policy-gradient methods are inherently high-variance. Implement these stabilization protocols:

- Use Advantage Estimation: Replace Monte Carlo returns with advantage estimates (A=Q-V). Implement Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) with λ typically between 0.92 and 0.98.

- Implement a Critic Network (Actor-Critic): Train a separate value network (critic) to estimate state values, providing a stable baseline for the policy update.

- Gradient Clipping: Clip policy gradients by norm (max norm ~0.5) or value (clamp between -0.5, 0.5) to prevent explosive updates.

Q3: How do I handle invalid molecular actions (e.g., adding a bond to a non-existent atom) and the resulting sparse reward problem? A3:

- Invalid Action Masking: At each step, programmatically compute all chemically invalid actions (valency violations, disconnected structures) and set their logits from the policy network to

-infbefore the softmax, ensuring they are never sampled. - Reward Shaping: Do not rely solely on a final property score (e.g., logP). Design intermediate rewards for:

- Penalizing invalid step attempts (small negative reward).

- Rewarding progress towards desired functional groups or scaffolds.

Q4: What are the best practices for representing the molecular state (St) and defining the action space (At) for an RL agent? A4: The choice is critical for efficient search.

Table 1: Common State and Action Space Representations

| Component | Option 1: String-Based (SMILES/SELFIES) | Option 2: Graph-Based |

|---|---|---|

| State (S_t) | A partial SMILES/SELFIES string. | A graph representation (atom/feature matrix, adjacency matrix). |

| Action (A_t) | Append a character from a vocabulary (e.g., 'C', '=', '1', '('). | Add an atom/bond, remove an atom/bond, or modify a node/edge feature. |

| Pros | Simple, fast, large existing literature. | More natural for molecules, guarantees valence correctness. |

| Cons | High rate of invalid SMILES; SELFIES mitigates this. | More complex model architecture required (Graph Neural Network). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard REINFORCE with Baseline for Molecular Optimization Objective: Maximize a target property (e.g., QED) using a SMILES-based generator.

- Agent Setup: Use an RNN (GRU/LSTM) as the policy network πθ. Initialize a separate but similar RNN as the value network (baseline) Vφ.

- Episode Generation: For N episodes, generate a molecule by sampling tokens from πθ until the terminal token is produced. Record states (St), actions (At), and rewards (Rt=0 until terminal step).

- Reward Assignment: Compute the target property (e.g., QED, SAScore) for the finalized valid molecule. Assign this reward to all steps (Rt = RT for all t) of the episode. Invalid molecules receive reward R = 0.

- Baseline Computation: For each state St, compute the estimated value Vφ(S_t).

- Gradient Calculation: Update policy parameters θ: Δθ = α Σt (Rt - Vφ(St)) ∇θ log πθ(At\|St). Update value parameters φ to minimize (Rt - Vφ(S_t))².

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 for M iterations.

Protocol 2: Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) for Scaffold-Constrained Generation Objective: Explore novel analogues within a defined molecular scaffold.

- Environment: Define the action space as adding atoms/fragments only to specified attachment points on a fixed core scaffold. Invalid actions are masked.

- Collection: Let the current policy π_θ interact with the environment to collect a batch of T trajectories (states, actions, rewards, dones).

- Advantage Estimation: Compute rewards-to-go Rt and advantages Ât using GAE across the batch.

- PPO-Clip Loss: Optimize the surrogate objective: L(θ) = Et[min( rt(θ) * Ât , clip(rt(θ), 1-ε, 1+ε) * Ât )], where rt(θ) = πθ(At\|St) / πθold(At\|S_t). Typical ε=0.2.

- Update: Perform K (e.g., 4) epochs of gradient descent on L(θ) using the collected batch before gathering new data.

Diagrams

Diagram Title: RL Agent Interaction with Chemical Space

Diagram Title: Policy Gradient Molecular Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for RL-based Molecular Design Experiments

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| RL Framework | Provides algorithms (PPO, DQN), environments, and training utilities. | Stable-Baselines3, Ray RLlib. Facilitates rapid prototyping. |

| Cheminformatics Library | Handles molecular I/O, fingerprinting, validity checks, and property calculation. | RDKit, Open Babel. Essential for reward function and state representation. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Library for building and training policy & critic neural networks. | PyTorch, TensorFlow. PyTorch is often preferred for research flexibility. |

| Molecular Representation | Defines the fundamental building blocks and grammar for generation. | SELFIES (recommended over SMILES for validity), DeepSMILES. |

| Property Prediction Model | Provides fast, differentiable reward signals (e.g., binding affinity, solubility). | A pre-trained Graph Neural Network (GNN) or Random Forest model. |

| Orchestration & Logging | Manages experiment queues, hyperparameter sweeps, and tracks results. | Weights & Biases (W&B), MLflow, TensorBoard. Critical for reproducibility. |

Active Learning and Uncertainty Sampling in High-Throughput Virtual Screening

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: The active learning loop appears to be "stuck," repeatedly selecting compounds with similar, high-uncertainty scores but not improving the model's overall predictive accuracy for the desired property. What could be the cause and solution?

A: This is a classic sign of over-exploration within a narrow, uncertain region of chemical space, neglecting exploitation of potentially promising areas. The issue often stems from the uncertainty sampling function.

- Cause: The algorithm may be sampling exclusively from the "decision boundary," where model predictions are close to 0.5 (for classification) or have high variance (for regression), but these regions may be sparse or noisy.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Data Quality: Check the experimental data for the initially labeled set. High noise in the training data prevents the model from establishing a reliable decision boundary.

- Implement Hybrid Query Strategies: Move from pure uncertainty sampling to a balanced strategy. Combine uncertainty with a measure of exploitation, such as:

- Expected Model Change: Query points that would cause the largest change to the current model.

- Thompson Sampling: Balance uncertainty with the predicted probability of success.

- Cluster-Based Diversity: After ranking by uncertainty, select the top k candidates from different structural clusters to ensure chemical diversity.

- Adjust Acquisition Function: Introduce a trade-off parameter (β) to balance exploration (uncertainty) and exploitation (predicted activity). Formally, score compounds using:

Score = (Predicted Activity) + β * (Uncertainty).

Q2: During batch-mode uncertainty sampling, the selected batch of compounds for experimental testing lacks chemical diversity, leading to redundant information. How can this be addressed?

A: This occurs when sequential queries are correlated. The solution is to incorporate a diversity penalty directly into the batch selection algorithm.

- Solution: Use Batch-Balanced Sampling (e.g., using K-Means or MaxMin distance).

- Rank all unlabeled compounds in the pool by their uncertainty score.

- Select the top N x M candidates (where N is your final batch size, and M is an oversampling factor, e.g., 10).

- Cluster these pre-selected candidates using a rapid fingerprint-based method (ECFP4) and a diversity metric like Tanimoto distance.

- From each cluster, select the candidate with the highest uncertainty score until the desired batch size N is filled.

Q3: The performance of the active learning model degrades significantly when applied to a new, structurally distinct scaffold not represented in the initial training set. How can we improve model transferability?

A: This indicates the model has overfit to the explored region and fails to generalize—a critical failure in balancing exploration across broader chemical space.

- Cause: The initial training set and subsequent queries lacked sufficient scaffold diversity to learn generally applicable structure-activity relationships.

- Mitigation Protocol:

- Initial Seed Design: Begin the active learning loop with a structurally diverse set of compounds, validated by a metric like Scaffold Tree analysis. Do not start with a single chemical series.

- Incorporate Domain Awareness: Use a multi-armed bandit framework at the scaffold level. Allocate a portion of each batch (e.g., 20%) to explicitly sample from under-explored molecular scaffolds, regardless of their immediate uncertainty within their own region.

- Model Choice: Employ models with better generalization properties, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which can learn more fundamental features than fingerprint-based models, or use ensembles of models trained on different descriptor sets.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Query Strategies in a Virtual Screening Campaign for Kinase Inhibitors

| Query Strategy | Compounds Tested | Hit Rate (%) | Novel Active Scaffolds Found | Avg. Turnaround Time (Cycles to Hit) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling | 5000 | 1.2 | 3 | N/A | Inefficient, high cost |

| Pure Uncertainty | 500 | 5.8 | 2 | Fast (2-3) | Gets stuck in local uncertainty maxima |

| Expected Improvement | 500 | 7.1 | 4 | Moderate (3-4) | Computationally more expensive |

| Hybrid (Uncertainty + Diversity) | 500 | 6.5 | 8 | Moderate (3-4) | Requires tuning of balance parameter |

| Thompson Sampling | 500 | 8.3 | 5 | Fast (2-3) | Can be sensitive to prior assumptions |

Table 2: Impact of Initial Training Set Diversity on Active Learning Outcomes

| Initial Set Composition | Size | Scaffold Diversity (Entropy) | Final Model Accuracy (AUC) | Exploration Efficiency (% of Space Surveyed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Scaffold | 100 | 0.1 | 0.91 (high) / 0.62 (low)* | 12% |

| Cluster-Based | 100 | 1.5 | 0.87 | 45% |

| Maximum Dissimilarity | 100 | 2.3 | 0.89 | 68% |

*Model accuracy was high within the explored scaffold but low when tested on a broad external validation set.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Hybrid (Exploration-Exploitation) Query Strategy

Objective: To select a batch of compounds for experimental testing that balances the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of predicted high-activity regions.

Methodology:

- Model Training: Train an ensemble of machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, GNN) on the current labeled set

L. - Prediction & Uncertainty: For all compounds in the unlabeled pool

U, generate predictions (meanμ(x)) and uncertainty estimates (standard deviationσ(x)across the ensemble). - Calculate Composite Score: For each compound

xinU, compute a score using the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function:UCB(x) = μ(x) + β * σ(x)whereβis a tunable parameter controlling the exploration-exploitation trade-off (β=0 for pure exploitation, high β for pure exploration). - Batch Selection with Diversity: Rank all compounds by their UCB score. From the top 20% of this ranked list, perform a maximum dissimilarity selection using the MaxMin algorithm with Tanimoto distance on ECFP4 fingerprints to select the final batch

B. - Experimental Testing & Iteration: Send batch

Bfor experimental validation. Add the new(compound, activity)pairs toLand retrain the models. Repeat from step 1.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Scaffold-Level Exploration in an Active Learning Run

Objective: Quantify how well an active learning strategy explores diverse molecular scaffolds, ensuring it does not prematurely converge.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Assignment: Using the RDKit toolkit, decompose all compounds in the database and each selected batch into their Bemis-Murcko scaffolds.

- Tracking: Maintain a cumulative set

Sof all unique scaffolds selected for testing up to the current cycle. - Calculate Metrics per Cycle:

- Novel Scaffold Rate: Number of newly encountered scaffolds in the current batch divided by the batch size.

- Cumulative Scaffold Coverage:

|S| / |S_total|, where|S_total|is the total number of unique scaffolds in the entire screening library. - Scaffold Entropy: Compute the Shannon entropy of the scaffold distribution in the selected set to measure diversity.

- Visualization: Plot Cumulative Scaffold Coverage vs. Cycle Number. A strategy that effectively balances exploration will show a steady, linear increase, while an over-exploitative strategy will plateau quickly.

Visualizations

Title: Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Title: Exploration vs. Exploitation in Query Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for an Active Learning-Driven Virtual Screening Pipeline

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Database | The vast, unlabeled chemical space pool for screening. Provides compounds for prediction and selection. | ZINC20, Enamine REAL, ChEMBL, in-house corporate library. |

| Molecular Descriptors/Features | Numeric representations of chemical structures for machine learning models. | ECFP4 fingerprints, RDKit 2D descriptors, 3D pharmacophores, Graph features (for GNNs). |

| Predictive Model Ensemble | The core machine learning model that predicts activity and estimates its own uncertainty. | Random Forest, Gaussian Process, Deep Neural Networks, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). |

| Acquisition Function Library | Algorithms that calculate the "value" of testing an unlabeled compound, defining the exploration-exploitation balance. | Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), Expected Improvement (EI), Thompson Sampling, entropy-based methods. |

| Diversity Selection Algorithm | Ensures structural breadth in batch selection to prevent over-concentration in one chemical region. | MaxMin Algorithm, K-Means Clustering on fingerprints, scaffold-based binning. |

| Automation & Orchestration Software | Manages the iterative loop: model training, prediction, batch selection, and data integration. | Python scripts (scikit-learn, PyTorch), KNIME, Pipeline Pilot, specialized platforms (e.g., ATOM). |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform | The physical system that provides experimental validation data for the selected compounds, closing the loop. | Automated assay systems (e.g., for enzyme inhibition, binding, cellular activity). |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My EA converges to a sub-optimal region of chemical space too quickly. How can I enhance exploration? A: Premature convergence often indicates an imbalance favoring exploitation (crossover) over exploration (mutation).

- Solution: Implement adaptive operator rates. Increase the mutation rate progressively as population diversity decreases. Use metrics like average Hamming distance between genotypes to trigger this change.

- Protocol: For a population of molecule fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4), calculate pairwise Tanimoto distance. If the mean distance falls below threshold T (e.g., 0.3), scale the mutation rate from a baseline (e.g., 0.05) by a factor of (T/mean_distance).

Q2: After high mutation, my algorithm fails to refine promising leads. How can I improve exploitation? A: Excessive exploration via mutation disrupts beneficial building blocks (substructures).

- Solution: Introduce a local search operator alongside standard mutation. Use a two-stage protocol: 1) High-probability crossover with low-probability mutation for exploitation. 2) For the best 10% of solutions, apply a deterministic local search (e.g., a small set of predefined, "smart" R-group substitutions).

- Protocol: After each generation, clone the top-performing individuals. Apply a limited molecular modification set (e.g., from a targeted library of bioisosteres) to each clone and evaluate. Re-insert improved clones.

Q3: How do I quantitatively decide the crossover vs. mutation rate for my molecular design problem? A: The optimal ratio depends on the landscape roughness and size of your chemical space.

- Solution: Perform an initial parameter grid search using a small subset of your objective function (e.g., a fast docking score proxy).

- Protocol: Run 10-generation trials across the following grid. Use the best-performing pair for your full experiment.

| Crossover Rate | Mutation Rate | Trial Performance (Avg. Fitness) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 0.05 | +125.4 | Fast early gain, then plateau. |

| 0.7 | 0.2 | +118.1 | Slower gain, broader search. |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | +101.7 | High diversity, slow convergence. |

| 0.8 | 0.15 | +129.8 | Best balance for this test case. |

Q4: The algorithm's performance is highly variable between runs. How can I stabilize it? A: High stochasticity from operator imbalance reduces reproducibility.

- Solution: Incorporate elitism and use a higher crossover rate on elite individuals. Implement a duplicate removal step after mutation to maintain diversity without sacrificing good solutions.

- Protocol: 1) Preserve the top 5% of solutions unchanged to the next generation (elitism). 2) Apply crossover with a rate of 0.85 to the elite and next 40% of solutions. 3) Apply a higher mutation rate (0.2) to the remaining 55%. 4) Use hashing of molecular fingerprints to detect and replace duplicates with random novel individuals.

Q5: How can I design a crossover operator that respects chemical synthesis feasibility? A: Standard one-point crossover on SMILES strings often generates invalid or nonsensical molecules.

- Solution: Use a fragment-based or reaction-aware crossover.

- Protocol: 1) Fragment parent molecules at retrosynthetically interesting bonds (e.g., using the RECAP method). 2) Create a child by combining a large fragment from one parent with a compatible small fragment from another, ensuring the joining bond type is chemically valid. 3) Validate the child via a set of synthetic accessibility (SA) score filters.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Reagent | Function in EA for Chemical Search |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for molecule manipulation, fingerprint generation, and validity checks. |

| ECFP/FCFP Fingerprints | Fixed-length vector representations of molecular structure for calculating genetic distances and similarity. |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score Filter | Computational metric (often rule-based) used as a penalty in the fitness function to bias search towards synthesizable compounds. |

| Target-specific Scoring Function (e.g., docking score, QSAR model) | The primary fitness function that drives selection, quantifying the predicted biological activity of a candidate molecule. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables the parallel evaluation of thousands of candidate molecules per generation, essential for practical search times. |

| Standardized Molecular Fragmentation Library (e.g., BRICS) | Provides chemically sensible building blocks for creating intelligent crossover and mutation operators. |

EA Workflow with Operator Balance

Adaptive Operator Control Logic

Thompson Sampling and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my UCB1 algorithm converge prematurely to a sub-optimal compound, ignoring other promising regions of the chemical space?

- Answer: Premature convergence in UCB is often caused by an incorrectly set exploration parameter (

c) or insufficient initial sampling. UCB1 uses the formulaUCB(i) = μ_i + c * sqrt(ln(N) / n_i). Ifcis set too low, the algorithm will over-exploit seemingly good candidates before sufficiently exploring others. - Troubleshooting Guide:

- Increase Parameter

c: Systematically increase the exploration parameter (e.g., from 1 to 2, √2, or higher) in a controlled test run on a known benchmark library. - Implement Forced Initial Exploration: Run a round-robin phase where each compound in the initial library is tested at least 2-3 times before applying the UCB policy to ensure stable initial mean (

μ_i) estimates. - Check Reward Scaling: Ensure your biological assay output (e.g., IC50, binding affinity) is normalized appropriately. Very large reward values can dominate the

sqrt(ln(N) / n_i)term.

- Increase Parameter

FAQ 2: In Thompson Sampling for high-throughput virtual screening, my posterior distributions are not updating meaningfully. What could be wrong?

- Answer: This typically indicates a mismatch between your likelihood function (observation model) and the actual experimental noise, or an incorrectly defined prior.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Validate Likelihood Model: If you assume Gaussian noise, verify that your experimental replicates are roughly normally distributed. For binary outcomes (e.g., active/inactive), switch to a Beta-Bernoulli model.

- Inspect Prior Hyperparameters: For a Beta prior

Beta(α, β), overly strong priors (very largeα+β) will slow posterior updating. Start with weak, uninformative priors likeBeta(1,1). - Check for Data Logging Errors: Ensure that new experimental results are correctly associated with the sampled compound and are updating the correct posterior distribution parameters.

FAQ 3: How do I choose between UCB and Thompson Sampling for my automated chemical synthesis and testing platform?

- Answer: The choice hinges on the need for computational simplicity vs. incorporating probabilistic models.

- Use UCB if you require a deterministic, easy-to-implement policy with clear interpretability on the exploration-exploitation trade-off via the

cparameter. It is less computationally intensive. - Use Thompson Sampling if you have a reliable probabilistic model of the chemical space and assay noise, and you want to naturally balance exploration and exploitation by sampling from posteriors. It is often more performative but requires maintaining and sampling from distributions.

- Use UCB if you require a deterministic, easy-to-implement policy with clear interpretability on the exploration-exploitation trade-off via the

FAQ 4: My experimental batch results show high variance, causing both algorithms to perform poorly. How can I mitigate this?

- Answer: High experimental noise destabilizes both the reward estimates for UCB and the posterior updates for Thompson Sampling.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Implement Replication Protocols: Do not rely on single-point measurements. For top candidates, institute a rule of performing

k(e.g., k=3) technical or biological replicates. Use the average reward for algorithm updates. - Adaptive Batching for Thompson Sampling: Instead of sampling one compound at a time, sample a small batch. Use a technique like Batch Thompson Sampling, which enforces diversity within the batch by approximating the probability that each candidate is optimal.

- Apply Variance-Stabilizing Transforms: Transform your assay data (e.g., log transform for IC50 values) before feeding it to the bandit algorithm to reduce heteroscedasticity.

- Implement Replication Protocols: Do not rely on single-point measurements. For top candidates, institute a rule of performing

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Validation in Chemical Search

Protocol 1: Benchmarking UCB vs. Thompson Sampling on a Public Molecular Dataset

- Objective: Compare cumulative regret of UCB and Thompson Sampling strategies.

- Materials: Public dataset with pre-calculated molecular properties and target activities (e.g., ChEMBL, MOSES with simulated docking scores).

- Methodology:

- Step 1 - Simulation Setup: Define a discrete chemical library of N compounds. Use a known property (e.g., docking score, solubility) as the ground-truth reward.

- Step 2 - Noise Introduction: Add Gaussian noise (ε ~ N(0, σ²)) to the ground-truth reward to simulate experimental error.

- Step 3 - Algorithm Initialization:

- UCB1: Set exploration parameter

c(start with √2). - Thompson Sampling (Gaussian): Assume a Gaussian likelihood with known noise σ². Use a conjugate Normal prior for the mean reward of each compound.

- UCB1: Set exploration parameter

- Step 4 - Iterative Simulation: For T rounds (T << N), each algorithm selects a compound, observes a noisy reward, and updates its internal parameters (mean count for UCB, posterior for TS).

- Step 5 - Metrics: Calculate cumulative regret:

Regret(T) = Σ_t (μ* - μ_{I_t}), where μ* is the optimal reward and μ{It} is the reward of the chosen compound at round t.

Protocol 2: Integrating Thompson Sampling with a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) for Continuous Chemical Space Exploration

- Objective: Guide the synthesis of new compounds by sampling from a model that captures uncertainty in structure-activity relationships.

- Materials: Initial dataset of compound structures (SMILES) and assay results; BNN framework (e.g., using TensorFlow Probability or Pyro).

- Methodology:

- Step 1 - Model Training: Train a BNN to predict biological activity (

μ) and its epistemic uncertainty (σ) from molecular fingerprints or descriptors. - Step 2 - Acquisition: For each candidate in a virtual library, the BNN outputs a distribution of predicted activities. Sample once from this distribution for each candidate (Thompson Sampling principle).

- Step 3 - Selection: Select the candidate with the highest sampled value for synthesis and testing.

- Step 4 - Iterative Update: Add the new experimental result to the training set and update the BNN weights (or perform approximate online updates). Repeat from Step 2.

- Step 1 - Model Training: Train a BNN to predict biological activity (

Table 1: Comparison of UCB and Thompson Sampling Core Characteristics

| Feature | Upper Confidence Bound (UCB1) | Thompson Sampling (Beta-Bernoulli) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Deterministic optimism in the face of uncertainty | Probabilistic matching via posterior sampling |

| Key Parameter | Exploration constant c |

Prior hyperparameters α, β |

| Update Rule | Update empirical mean μ_i and count n_i |

Update posterior Beta(α + successes, β + failures) |

| Exploitation | Selects argmax of μ_i + c * sqrt(ln(N)/n_i) |

Samples from posteriors, selects argmax of sample |

| Advantage | Simple, deterministic, strong theoretical guarantees | Often better empirical performance, natural balance |

Table 2: Example Simulation Results on a 10,000 Compound Library (T=2000 rounds)

| Algorithm & Parameters | Cumulative Regret (Mean ± SD) | % Optimal Compound Found |

|---|---|---|

| UCB1 (c=1.0) | 342.5 ± 45.2 | 65% |

| UCB1 (c=√2) | 298.1 ± 32.7 | 82% |

| UCB1 (c=2.0) | 315.4 ± 41.5 | 78% |

| Thompson Sampling | 275.3 ± 28.9 | 88% |

| Random Selection | 1250.8 ± 120.4 | 12% |

Note: Simulated data for illustrative purposes. SD = Standard Deviation over 50 simulation runs.

Visualization: Algorithm Workflows

Title: UCB vs Thompson Sampling Bandit Workflows

Title: Closed-Loop Chemical Search with Thompson Sampling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bandit-Driven Chemical Research |

|---|---|

| Beta Distribution Priors (Beta(α,β)) | Conjugate prior for binary activity data (e.g., active/inactive in a primary screen). Enables efficient posterior updates in Thompson Sampling. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | Models continuous chemical space and predicts both expected activity and uncertainty for unexplored compounds, ideal for integration with UCB or TS. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (ECFP4) | Fixed-length vector representations of molecular structure. Serve as the input feature x for predictive models linking structure to activity. |

| Normalized Assay Output | A scaled reward signal (e.g., 0-100% inhibition, -log10(IC50)). Essential for stable algorithm performance and fair comparison between different assay types. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | Enables the physical realization of the algorithm's selected compound for testing, closing the loop in an autonomous discovery system. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Data | Provides the initial, sparse dataset of compound-activity pairs necessary to bootstrap the probabilistic model for the search. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During a Bayesian Optimization run, my molecular property predictor (DNN) returns NaN values, causing the search to crash. What are the likely causes and solutions?

A: This is typically a data or model instability issue.

- Cause 1: The search algorithm (e.g., SMILES GA) generated invalid or unstable molecular structures that the featurizer (e.g., RDKit descriptors) cannot process.

- Solution: Implement a robust chemical validity check and sanitization step before featurization. Use

rdkit.Chem.SanitizeMol()and catch exceptions.

- Solution: Implement a robust chemical validity check and sanitization step before featurization. Use

- Cause 2: The training data for the DNN was not properly normalized, and the search is exploring regions of chemical space with extreme descriptor values leading to explosive gradients.

- Solution: Apply standard scaling (Zero mean, unit variance) to training data. During search, use the same scaler to transform generated molecule features. Clip extreme values.

- Protocol: Implement a pre-prediction pipeline:

Generated SMILES -> Validity/Sanitization Check -> Featurization -> Check for NaN/Inf in features -> Scale using training scaler -> Predict.

Q2: My genetic algorithm (GA) for molecular optimization seems to be stuck in a local optimum, repeatedly generating similar high-scoring molecules without exploring new scaffolds. How can I improve the exploration?

A: This is a classic exploration-exploitation imbalance in the search algorithm.