Small Molecule Microarrays: A Comprehensive Guide to Sensitization, Applications, and Workflow Optimization in Drug Discovery

Small Molecule Microarrays (SMMs) represent a powerful high-throughput technology for profiling chemical-protein and chemical-RNA interactions, enabling rapid identification of therapeutic leads and chemical probes.

Small Molecule Microarrays: A Comprehensive Guide to Sensitization, Applications, and Workflow Optimization in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Small Molecule Microarrays (SMMs) represent a powerful high-throughput technology for profiling chemical-protein and chemical-RNA interactions, enabling rapid identification of therapeutic leads and chemical probes. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of SMM technology, including surface chemistry and immobilization strategies. It details methodological advances and diverse applications, from traditional protein targeting to the emerging frontier of RNA ligand discovery. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization parameters for robust assay development and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses with other screening methodologies, synthesizing key takeaways to illuminate future directions for biomedical research.

What Are Small Molecule Microarrays? Exploring Core Principles and Technological Evolution

Small Molecule Microarrays (SMMs) represent a powerful, miniaturized screening platform that has revolutionized early-stage drug discovery. This technology enables researchers to rapidly screen tens of thousands of compounds for interactions with diverse biological targets in a parallel and high-throughput manner [1]. The core principle involves robotically arraying and immobilizing small molecules onto functionalized glass slides, creating a dense microarray where each spot represents a unique compound [1] [2]. These arrays are then incubated with a target of interest, and binding events are detected, typically using fluorescent labeling strategies [1]. The high-throughput and miniaturized nature of the SMM-based binding assay allows for the screening of large panels of proteins or nucleic acids against extensive compound libraries in a relatively short time frame and at low sample cost [1] [2]. Over the last decade, SMMs have proven to be a general, robust, and scalable platform for discovering protein-small molecule interactions that lead to modulators of protein function, and their application has since expanded to include challenging targets such as RNA [1] [2].

The evolution of SMM technology is particularly significant within the context of chemical sensibilization research, which aims to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of chemical detection for biological targets. By providing a standardized, high-density format for compound-target interaction screening, SMMs serve as a foundational tool for sensibilizing discovery pipelines, enabling the identification of even weak binders that can be optimized into potent chemical probes or therapeutics. This is especially valuable for target classes traditionally deemed "undruggable," where SMMs offer a path to discover novel chemical starting points.

SMM Technology: Core Concepts and Workflow

Key Concepts and Immobilization Strategies

The utility of SMMs hinges on two critical components: the method of compound immobilization and the design of the array itself. Effective immobilization must present the small molecule in a accessible orientation while minimizing non-specific binding. Two primary strategies have been developed:

- Isocyanate-based Covalent Attachment: This heterogeneous display method allows for the creation of SMMs using compounds not intentionally synthesized for immobilization [1]. It is highly versatile, enabling the arraying of bioactive small molecules, including FDA-approved drugs, synthetic drug-like compounds, and natural products, directly from stock solutions without the need for specialized chemical handles. It is estimated that 77% of compounds in a typical screening collection are compatible with this method [1].

- Fluorous-based Homogeneous Display: This approach relies on compounds containing a fluorous tag for immobilization onto a corresponding fluorous-functionalized slide surface [1].

A typical SMM design consists of multiple sub-arrays printed simultaneously by a robotic printer equipped with multiple pins. Each sub-array can contain 196 to 256 individual spots, comprising both library compounds and essential controls such as fluorescent dyes for grid alignment and inactive compounds or DMSO as negative controls [2].

The Generic SMM Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard, target-agnostic workflow for a small molecule microarray screen, from slide preparation to hit identification.

Workflow Description: The process begins with the preparation of glass slides featuring chemically modified surfaces ready for compound immobilization [2]. The small molecule library is then robotically printed onto these slides to create the high-density microarray [1] [2]. Subsequently, the printed SMM is incubated with a fluorescently labeled biological target—which could be a protein, RNA, or other biomolecule—in a suitable binding buffer [2]. After incubation, the slide is washed extensively to remove any unbound target, ensuring that retained fluorescence is due to specific binding [2]. The dried slide is then imaged using a fluorescent scanner, and the resulting image is quantified using specialized microarray analysis software [2]. Spots exhibiting significantly higher fluorescence intensity than background levels are flagged as potential "hits" for further validation [2].

Application Note: Multi-Target RNA Screening on SMMs

Background and Rationale

RNA has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for a wide range of diseases, but a significant challenge in discovering RNA-binding small molecules is achieving target specificity [3] [4]. In a cellular environment, any small molecule must bind its intended RNA target amidst a crowded background of highly abundant RNAs, such as tRNA and rRNA [2]. Conventional SMM screening focuses on a single RNA target, which provides little direct information about a compound's potential for off-target binding. To address this, a multi-color imaging protocol was developed that enables the simultaneous screening of multiple RNA targets on a single SMM slide [2]. This approach allows for the direct assessment of binding selectivity during the primary screen, efficiently triaging compounds that bind promiscuously and prioritizing those with inherent specificity for the target of interest.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials:

- Glass slides with printed small molecule microarrays (see Support Protocol 1 in [2])

- LifterSlips Cover Slip (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat. no. 25X60I24789001LS)

- RNaseZAP Decontamination Solution

- 5' end-labeled RNA targets (e.g., labeled with AlexaFluor 647, AlexaFluor 532, or fluorescein)

- 10x PBS buffer, pH 7.4

- Tween 20

- RNase-free Tris buffer (1 M, pH 7.0)

- Potassium Chloride (≥99.0%)

- Magnesium Chloride (≥97.0%)

- Nuclease-free water

- 4-well rectangular polystyrene dishes

- Benchtop centrifuge

- Fluorescent Scanner (e.g., InnoScan 1100 AL)

Method:

- RNA Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve each fluorophore-labeled RNA in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of 100 µM. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

- Dilute labeled RNAs to 5 µM in an appropriate annealing buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl₂).

- Anneal the RNA for proper folding: heat to 95°C for 5 minutes, then allow to cool slowly to room temperature over 3-4 hours. Store annealed RNA at 4°C overnight.

SMM Incubation (Cover Slip Method):

- Decontaminate the workspace using RNaseZAP.

- Prepare a humidified incubation chamber by placing a wet Kimwipe in one well of a 4-well dish.

- Combine the differently labeled RNA targets in annealing buffer. The final concentration of each RNA in the mixture is typically 50-100 nM.

- Apply the RNA mixture to a LifterSlips cover slip. Carefully lower the SMM slide (printed-side down) onto the cover slip, ensuring the solution spreads evenly across the array.

- Place the slide assembly into the humidified chamber and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

Washing and Scanning:

- Carefully disassemble the slide and cover slip, then wash the slide by immersing it in a coplin jar containing wash buffer (1x PBS with 0.005% Tween 20) for 2 minutes. Repeat this wash twice with fresh buffer.

- Rinse the slide briefly in nuclease-free water and dry it using a benchtop centrifuge.

- Scan the slide using a fluorescent scanner equipped with lasers appropriate for the fluorophores used (e.g., 647 nm, 532 nm, and 488 nm lasers).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for SMM-based RNA Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Functionalized SMM Slides | Solid support for covalent immobilization of small molecule library compounds [2]. |

| LifterSlips Cover Slip | Ensures even distribution of the RNA solution over the microarray during incubation [2]. |

| Fluorophore-labeled RNAs | Enable detection of binding events; different colors allow for simultaneous, target-specific screening [2]. |

| RNaseZAP | Critical for eliminating RNase contamination from surfaces and tools, preserving RNA integrity [2]. |

| Annealing Buffer (KCl, MgCl₂) | Provides the ionic conditions necessary for proper folding of RNA into its native, functional 3D structure [2]. |

| Wash Buffer (PBS + Tween 20) | Removes unbound and weakly associated RNA from the microarray, reducing background signal [2]. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Following fluorescent scanning, image analysis is performed using specialized software (e.g., Innopsys Mapix, GenePix Pro). The software aligns a grid to the sub-arrays using the fluorescent dye controls and quantifies the fluorescence intensity for every spot at each wavelength [2].

- Hit Identification: For each RNA target, a normalized fluorescence intensity is calculated for each compound spot. Compounds with intensities significantly exceeding the background (e.g., Z-score > 3) are considered initial hits for that specific RNA.

- Selectivity Assessment: The fluorescence data for a single compound across all three color channels is compared directly. A selective binder for the primary target (e.g., NRAS rG4) will show a high signal in the corresponding channel (e.g., red, AlexaFluor 647) but low signals in the other channels (e.g., green and blue for tRNA and rRNA). This provides an immediate selectivity profile [2].

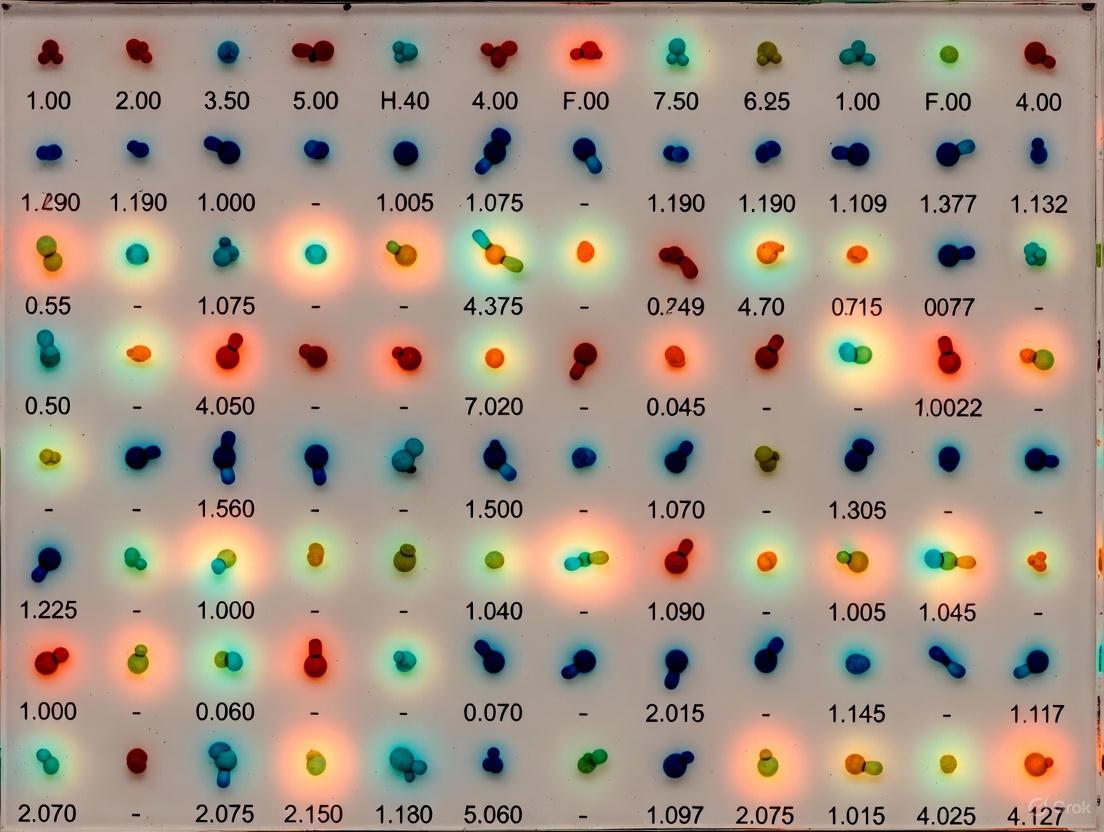

The following diagram illustrates the logic of data interpretation and hit prioritization based on the multi-color screening results.

Quantitative Data Presentation

The quantitative output from a multi-color SMM screen can be efficiently summarized for comparison, as shown in the table below, which uses hypothetical data based on the described methodology.

Table 2: Example Quantitative Output from a Multi-Color SMM Screen Targeting NRAS rG4 RNA

| Compound ID | Fluorescence Intensity (NRAS rG4 - Red) | Fluorescence Intensity (tRNA - Blue) | Fluorescence Intensity (rRNA - Green) | Z-Score (NRAS rG4) | Selectivity Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd A | 45,200 | 1,150 | 980 | 18.5 | Selective Binder |

| Cmpd B | 38,500 | 32,800 | 41,100 | 15.8 | Promiscuous Binder |

| Cmpd C | 2,100 | 1,950 | 2,300 | 0.2 | Inactive |

| Cmpd D | 52,100 | 5,200 | 3,100 | 21.3 | Selective Binder |

Small Molecule Microarrays have firmly established themselves as a powerhouse technology in high-throughput screening. Their evolution from single-target protein screens to sophisticated, multi-target applications like RNA selectivity screening demonstrates their remarkable versatility and power. The multi-color imaging protocol detailed herein exemplifies how SMM technology can be adapted to address a central challenge in drug discovery—achieving selectivity—at the earliest stages of screening. By enabling the parallel assessment of binding against multiple targets in a single, miniaturized experiment, SMMs provide a robust framework for chemical sensibilization research, yielding richer datasets and higher-quality hit compounds. As the demand for targeting complex biomolecules like RNA continues to grow, SMMs, particularly when coupled with advanced readouts like multi-color imaging, will remain an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to unlock new therapeutic opportunities.

Deciphering the human functional proteome, which encompasses thousands of characterized proteins and uncharacterized predicted gene products, is a primary challenge in the post-genomic era [5]. Processes like alternative splicing and post-translational modification further expand this complexity, resulting in an estimated >10^6 biomolecules required to maintain human cell integrity [5]. Traditional, labor-intensive drug discovery methods, long reliant on cumbersome trial-and-error, are fundamentally inadequate for systematically probing this vast biological space [6].

This document outlines the use of Small-Molecule Microarrays (SMMs) as a powerful tool to overcome this throughput challenge. SMMs provide a general binding assay compatible with nearly any protein without advanced knowledge of its structure or function, enabling the high-throughput identification of specific small-molecule probes for diverse proteins [5]. By miniaturizing and parallelizing ligand discovery, SMMs serve as a critical enabling technology for chemical sensibilization research, facilitating the exploration of cellular response mechanisms at a molecular level [7].

Small-Molecule Microarrays: A Platform for High-Throughput Ligand Discovery

Core Principle and Workflow

Small-Molecule Microarrays (SMMs) involve the organized immobilization of hundreds to thousands of distinct small molecules on a functionalized glass slide in a dense, addressable grid [5] [8]. This setup functions as a miniaturized, highly parallel binding assay. The fundamental workflow involves incubating a purified protein or cell lysate over the array, followed by the detection of binding events, typically via fluorescently labeled antibodies or expressible tags like GFP [5].

The subsequent workflow after a primary SMM screen is critical for validation. Positives identified from the microarray are then subjected to secondary binding assays (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance, SPR) to confirm direct interaction and determine affinity, and finally evaluated in functional or phenotypic assays to determine their biological effect [5].

Key Advantages in Addressing the Throughput Challenge

The advantages of SMMs directly address the core bottlenecks in conventional screening:

- Massive Throughput and Miniaturization: SMMs enable the simultaneous screening of thousands of compounds against a protein target in a single experiment, drastically reducing reagent consumption and cost [5] [8].

- Generality: The assay can identify ligands for proteins in the absence of prior knowledge about their structure or function, making it ideal for probing uncharacterized proteins [5].

- Direct Screening from Lysates: SMMs are compatible with screens using cell lysates containing endogenous or overexpressed proteins. This bypasses the need for protein purification and allows proteins to be screened in a more native state, potentially with relevant post-translational modifications or within protein complexes [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Screening Approaches in Drug Discovery

| Feature | Traditional HTS (Well-Based) | Phenotypic Screening | SMM-Based Binding Screen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High | Moderate | Very High (Miniaturized) |

| Information Required | Functional assay knowledge | Cellular model | None (binding-based) |

| Target Identification | Directly known | Requires deconvolution | Directly known |

| Compatibility with Lysates | Low | Not Applicable | High |

| Primary Readout | Functional | Phenotypic | Binding |

Experimental Protocols for SMM-Based Ligand Discovery

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Small-Molecule Microarrays

Objective: To create a functional SMM using a covalent immobilization strategy.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Functionalized Slides: Aldehyde-, epoxy-, or maleimide-coated glass slides.

- Small-Molecule Library: A diverse collection of compounds, typically featuring functional groups compatible with the slide chemistry (e.g., primary amines for aldehyde slides).

- Microarray Spotter: A robotic contact or non-contact printer capable of dispensing nanoliter volumes.

- Printing Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or other suitable buffer, often with additives like glycerol to prevent evaporation during printing.

Methodology:

- Compound Preparation: Dissolve small molecules in a suitable printing buffer (e.g., DMSO/PBS mixture) to a concentration typically ranging from 0.1 to 1 mM.

- Arraying: Using a microarray spotter, transfer nanoliter volumes of each compound solution onto the functionalized slides, creating features with diameters of 50–300 μm. Include control compounds (known binders and non-binders) in the array layout.

- Immobilization: After printing, incubate the slides in a humidified chamber for 4-16 hours to allow for complete covalent coupling between the small molecules and the slide surface.

- Quenching and Washing: Quench unreacted surface groups by incubating the slides with a solution containing a reactive species that does not interfere with the assay (e.g., a solution of bovine serum albumin, BSA, for aldehyde slides). Wash the slides thoroughly with buffer and dry by centrifugation.

Table 2: Common SMM Immobilization Chemistries [5]

| Attachment Method | Surface Group | Compound Group | Bond Formed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Addition | Maleimide | Thiol | Thioether |

| Oxime Formation | Glyoxylyl | Aminoxyl | Oxime |

| Amide Formation | Activated Ester | Amine | Amide |

| 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition | Terminal Alkyne | Azide | Triazole |

| Staudinger Ligation | Phosphane | Azide | Amide |

| Non-covalent | Streptavidin | Biotin | Streptavidin-Biotin |

Protocol 2: Screening and Hit Identification with a Fluorescence Readout

Objective: To identify small-molecule ligands for a protein of interest using an SMM.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Target Protein: Purified protein or cell lysate containing the protein.

- Detection Antibody: A fluorescently labeled primary antibody against the protein, or an antibody against an epitope tag (e.g., His-tag, FLAG-tag).

- Blocking Buffer: A solution like BSA or non-fat milk in TBST to prevent non-specific binding.

- Assay Buffer: A physiologically relevant buffer such as Tris-buffered saline (TBS) or PBS, often with a detergent like Tween-20.

Methodology:

- Blocking: Incubate the fabricated SMM with blocking buffer for 1 hour to minimize non-specific adsorption.

- Protein Incubation: Apply the target protein (at a concentration of 0.1–1 µg/mL in assay buffer) to the array and incubate for 1-2 hours in a humidified chamber.

- Washing: Wash the array multiple times with assay buffer to remove unbound protein.

- Detection: Incubate the array with a fluorescently labeled antibody for 1 hour. Use an antibody concentration optimized for signal-to-noise ratio.

- Final Washing and Scanning: Perform a final series of washes, dry the slide by centrifugation, and immediately scan it using a standard microarray scanner.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity of each feature. Hits are identified as features with a signal significantly above the background and negative controls.

Visualization of SMM Screening Workflow and Data Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated SMM screening workflow, from array fabrication to hit validation and its role in a broader chemical biology data pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SMM Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Glass Slides | Solid support for covalent or non-covalent immobilization of small molecules. Common types include aldehyde, epoxy, and maleimide [5]. |

| Diverse Small-Molecule Libraries | Collections of compounds for immobilization. Sources include products of diversity-oriented synthesis, known bioactive compounds, and natural products [5]. |

| Microarray Spotter | Robotic instrument for precise, high-density deposition of nanoliter compound volumes onto slides [5]. |

| Epitope-Tagged Proteins | Proteins engineered with tags (e.g., His, FLAG, GST) for simplified purification and detection using standardized antibody methods during screening [5] [8]. |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Antibodies | Detection reagents used to identify protein binding to arrayed small molecules via microarray scanner [5]. |

| Cell Lysates | Crude extracts from cells expressing a target protein, enabling screening without protein purification and in a more biologically relevant context [5]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Instrument | Biosensor system used for secondary validation of SMM hits to confirm binding and quantify affinity kinetics (e.g., dissociation constant, KD) [5]. |

Microarray technology represents a paradigm shift in high-throughput screening, enabling the parallel analysis of thousands of molecular interactions in a single experiment. Within the field of small molecule microarray (SMM) chemical sensibilization research, three principal technological formats have emerged: covalent, non-covalent, and solution-phase microarrays. Each platform offers distinct advantages and challenges for profiling small molecule interactions with diverse biological targets including proteins, nucleic acids, and complex cellular lysates. The fundamental principle underlying all microarray technologies involves the miniaturized, ordered arrangement of probe molecules on a solid surface to create a high-density screening platform where binding events can be detected and quantified [9] [10].

The evolution of microarray technologies began with nucleic acid arrays in the 1990s, pioneered by techniques such as colony hybridization and later advanced by robotic spotting systems that enabled the creation of ordered arrays [9]. This foundation was subsequently adapted for small molecule applications, with the first SMMs described in 1999 by MacBeath and colleagues [11] [5]. Since their inception, SMMs have become indispensable tools for chemical genetics and drug discovery, providing researchers with powerful methods to identify ligands for proteins without prior knowledge of protein structure or function [5]. The technology has progressively advanced to address increasingly complex biological questions, from identifying inhibitors of transcription factors to profiling enzyme activities and characterizing RNA-binding compounds [10] [12].

Comparative Analysis of Microarray Immobilization Strategies

The performance and application suitability of microarrays are fundamentally determined by their immobilization chemistry. The choice between covalent, non-covalent, and solution-phase approaches influences multiple experimental parameters including display orientation, molecular stability, binding accessibility, and detection sensitivity.

Table 1: Comparison of Microarray Immobilization Technologies

| Immobilization Method | Key Features | Optimal Applications | Throughput Capacity | Detection Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Attachment | Stable, oriented immobilization; Requires specific functional groups | High-density screening; Quantitative binding studies | 10,000-20,000 targets per array [13] | Potential interference from covalent linkage |

| Non-Covalent Attachment | Simple preparation; No probe modification needed | Rapid screening; Polysaccharide & tissue lysate arrays | Varies by surface capacity | Variable stability; Background interference |

| Solution-Phase Microarrays | Mimics physiological conditions; No immobilization required | Activity-based profiling; Enzyme-substrate studies | Limited by solution containment | Specialized detection systems needed |

Covalent Immobilization Strategies

Covalent immobilization creates stable, irreversible bonds between small molecules and functionalized solid surfaces, ensuring consistent probe presentation throughout rigorous assay conditions. This approach requires specific chemical functionalities on both the small molecule and the surface to facilitate covalent bond formation.

Multiple covalent attachment strategies have been developed, each employing distinct coupling chemistry. Isocyanate-functionalized surfaces provide broad reactivity toward nucleophilic groups commonly found in small molecule libraries, including hydroxyl, amine, and thiol functionalities, without requiring pre-derivatization of screening compounds [12]. This chemistry enables rapid production of SMM chips from existing compound collections, typically using 10 mM stocks in DMSO with piezoelectric printing technologies depositing sub-nanoliter volumes (200 pL) per spot [12]. Alternative covalent approaches include maleimide-thiol coupling for Michael addition, epoxy-hydrazide reactions, and photoactivatable cross-linking strategies using nitroveratryloxycarbonyl (NVOC)-protected hydroquinone groups that release upon UV irradiation to generate benzoquinone for Diels-Alder reactions with cyclopentadiene-tagged small molecules [11] [5].

The significant advantage of covalent immobilization lies in its stability and reproducibility. Covalently bound small molecules withstand stringent washing conditions necessary to reduce nonspecific binding, thereby improving signal-to-noise ratios in binding assays. Additionally, covalent attachment enables controlled orientation of displayed molecules, potentially enhancing their accessibility to target proteins [14] [5]. However, this method requires careful consideration of the attachment site on each small molecule to ensure that the covalent linkage does not sterically hinder the binding interface or alter molecular properties critical for target recognition.

Non-Covalent Immobilization Strategies

Non-covalent immobilization relies on physicochemical interactions including adsorption, electrostatic forces, and affinity binding to attach small molecules to array surfaces. This approach offers simplicity and avoids the need for specific functional groups on the small molecules, making it particularly valuable for screening complex natural products or compound collections with diverse structural features.

Electrostatic adsorption represents the simplest non-covalent approach, wherein negatively charged phosphate backbones of nucleic acids or sulfate groups of polysaccharides interact with positively charged surface coatings such as poly-L-lysine or aminosilane [14] [15]. Similarly, nitrocellulose membranes provide a porous, high-binding-capacity substrate that can passively adsorb proteins through hydrophobic and polar interactions, with demonstrated capacity up to 500 times greater than functionalized glass slides [16]. This exceptional binding capacity makes nitrocellulose particularly suitable for reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPA) where tissue lysates containing low-abundance proteins are immobilized and probed with specific antibodies [16].

Affinity-based non-covalent methods utilize specific molecular recognition systems such as streptavidin-biotin interactions. In this approach, small molecules conjugated with biotin tags are immobilized on streptavidin-functionalized glass slides, providing uniform orientation and strong yet non-covalent attachment (dissociation constant Kd ≈ 10^-15 M) [13]. This method has been successfully employed to screen one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) combinatorial libraries against intracellular proteins from Jurkat cell lysates, identifying multiple ligand candidates with binding affinities in the micromolar range [13]. While non-covalent methods offer implementation simplicity, they may suffer from variable stability under different buffer conditions and potential inconsistencies in molecular orientation, which can affect binding accessibility and assay reproducibility.

Solution-Phase Microarray Platforms

Solution-phase microarrays represent an alternative approach that maintains small molecules in their native soluble state while still enabling high-throughput screening. These systems utilize various containment strategies to prevent cross-contamination while preserving the physiological relevance of solution-phase interactions.

One innovative solution-phase methodology involves DNA-encoded libraries, where small molecules are covalently linked to unique DNA tags that facilitate both their identification and immobilization through hybridization to complementary DNA arrays [11]. This approach effectively converts a solution-binding event into a spatially addressable detection system, combining the benefits of traditional solution-phase chemistry with the multiplexing capabilities of microarray platforms. Similarly, ribosome display techniques have been adapted to microarray formats, enabling the simultaneous isolation and identification of enzyme subclasses from complex mixtures using small-molecule probes on DNA microarrays [11].

The principal advantage of solution-phase systems is the maintenance of unconstrained molecular interactions that closely mimic physiological conditions, avoiding potential artifacts associated with surface immobilization. Additionally, these systems circumvent the need for direct chemical modification of small molecules for surface attachment, preserving their native structural and functional properties. However, solution-phase approaches typically require specialized detection methods and may face challenges with evaporation, cross-contamination, and limited density compared to solid-phase arrays.

Experimental Protocols for Microarray Implementation

Protocol 1: Covalent Small Molecule Microarray Production and Screening

This protocol describes the fabrication of covalent small molecule microarrays using isocyanate chemistry and their application for protein binding studies, adapted from established methodologies [5] [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Isocyanate-functionalized glass slides (commercially available)

- Small molecule library (10 mM in 100% DMSO)

- Arraying robot with piezoelectric printing capability (e.g., Arrayjet Mercury)

- Blocking solution: 1% BSA in PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20)

- Target protein in appropriate binding buffer

- Detection reagents: primary antibody (if needed) and fluorescently labeled secondary antibody

- Microarray scanner (e.g., Innopsys 710 AL with 635 nm channel)

Procedure:

- Slide Preparation: Place isocyanate-functionalized slides in the arraying robot. Ensure humidity control (40-60% RH) to prevent evaporation during printing.

- Microarray Printing: Program the arrayer to deposit 200 pL of each small molecule solution in 6 replicate spots per compound. For a 10,000-compound library, this generates arrays with 12,672 total spots when including controls.

- Immobilization: Incubate printed slides overnight at room temperature in a desiccator to facilitate complete covalent coupling.

- Blocking: Wash slides with PBST and incubate with blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature to minimize nonspecific binding.

- Protein Binding: Incubate the microarray with target protein (1-10 μg/mL in binding buffer) for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Detection: For direct detection, use fluorescently labeled proteins. For indirect detection, incubate with primary antibody (1-2 hours) followed by fluorescent secondary antibody (1 hour).

- Image Acquisition: Scan slides at PMT 35 using the 635 nm channel. Extract fluorescence intensity values using microarray analysis software (e.g., Mapix v8.5.0).

- Data Analysis: Calculate signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) for each spot. Identify hits as compounds with SNR > 3 standard deviations above background.

Troubleshooting Notes: Inconsistent spot morphology may indicate humidity fluctuations during printing. High background signal may require increased stringency in washing steps or optimization of blocking conditions. For cell lysate screening, include protease inhibitors throughout the binding and washing steps.

Protocol 2: Non-Covalent Protein Microarray Using Nitrocellulose Substrates

This protocol details the creation of reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPA) on nitrocellulose-coated slides for antibody profiling applications, utilizing the high binding capacity of porous substrates [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Porous nitrocellulose (PNC)-coated slides (e.g., ONCYTE from Grace Bio-Labs)

- Cell or tissue lysates in appropriate lysis buffer

- Contact printer or non-contact arrayer

- Blocking solution: 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST

- Primary antibody against target protein

- Fluorescently labeled secondary antibody

- Microarray hybridization chamber (e.g., HybriSlip or ProPlate)

- Microarray scanner

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare lysates from cells or tissues of interest. Clarify by centrifugation and determine protein concentration.

- Array Printing: Spot 1-2 nL of each lysate onto nitrocellulose slides in replicate patterns. Include positive and negative controls.

- Immobilization: Air-dry slides for 1 hour to allow complete adsorption of proteins to the nitrocellulose matrix.

- Blocking: Incubate arrays with blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature with agitation.

- Antibody Probing: Incubate arrays with primary antibody (diluted in blocking solution) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash slides 3 times with TBST for 5 minutes each with agitation.

- Secondary Detection: Incubate with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (1 hour, room temperature, protected from light).

- Image Acquisition: Scan slides using appropriate fluorescence settings. Analyze signal intensity using specialized software.

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for quantitative assessment of protein expression in comparative studies, tumor biology, and signaling pathway analysis. The high binding capacity of nitrocellulose enables detection of low-abundance proteins and small expression changes (<1.5%) that might be missed on conventional surfaces [16].

Research Reagent Solutions for Microarray Applications

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microarray Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Surfaces | Isocyanate-glass, Epoxy-coated slides, Streptavidin-coated slides, Porous nitrocellulose films | Covalent attachment (isocyanate, epoxy), affinity capture (streptavidin-biotin), or high-capacity protein adsorption (nitrocellulose) [14] [16] [12] |

| Detection Systems | Fluorescent antibodies (Alexa Fluor 647), Fluorescently labeled RNA (Cy5), Label-free systems (OI-RD) | Target detection: fluorescent methods offer sensitivity; label-free systems preserve native protein function [13] [12] |

| Printing Technologies | Piezoelectric non-contact printers (Arrayjet Mercury), Contact printers (OmniGrid100) | Miniaturized deposition of compounds: non-contact for delicate surfaces, contact for higher viscosity solutions [13] [12] |

| Incubation Chambers | HybriSlip, ProPlate multi-well modules | Controlled sample application and mixing during binding assays; ProPlate enables parallel processing of multiple samples [16] |

| Blocking Agents | BSA (1-5%), non-fat dry milk (5%) | Minimize nonspecific binding to surface and reduce background signal [12] |

Visualization of Microarray Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Microarray Workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete process from compound library preparation through data analysis, highlighting decision points between covalent and non-covalent surfaces and alternative detection methodologies.

Diagram 2: Binding Detection Methodologies. This diagram outlines the three principal detection strategies used in microarray screening, highlighting both labeled and label-free approaches with their respective components and workflows.

Applications and Future Perspectives in Chemical Sensibilization Research

Small molecule microarrays have demonstrated exceptional utility across diverse research applications, from basic protein-ligand interaction studies to drug discovery pipelines. The technology has successfully identified novel ligands for challenging targets including transcription factors, kinases, proteases, and structural RNAs [10] [5] [12]. In one notable application, SMM screening of a 3,780-compound library against the yeast transcription factor Ure2p identified a specific binder (Kd = 7.5 μM) that inhibited Ure2p activity in vivo and derepressed a downstream glucose-sensitive transcriptional pathway [11]. Similarly, SMMs have been employed to discover inhibitors of microRNA-21 processing and ligands for the PreQ1 riboswitch RNA, highlighting the platform's versatility against diverse target classes [12].

The integration of SMMs with functional proteomics represents a particularly promising direction for chemical sensibilization research. Rather than merely detecting binding events, advanced microarray platforms now incorporate activity-based readouts that probe enzymatic functions and cellular signaling pathways [10] [11]. For instance, SMMs featuring coumarin derivatives conjugated with enzyme recognition domains have enabled the fingerprinting and characterization of proteins based on their enzymatic activities, moving beyond simple binding to functional assessment [11]. Similarly, reverse-phase protein arrays composed of tissue lysates printed on nitrocellulose substrates have enabled quantitative profiling of protein expression and post-translational modifications in clinical specimens, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [16].

Future developments in microarray technology will likely focus on enhancing sensitivity, expanding content density, and integrating multi-parametric readouts. Label-free detection methods such as oblique-incidence reflectivity difference (OI-RD) microscopy offer particular promise for quantifying binding affinities without potentially perturbing fluorescent labels [13]. As these technologies mature, SMM platforms will continue to evolve as indispensable tools for chemical biology, enabling researchers to comprehensively map small molecule interactions across the proteome and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic agents.

Small molecule microarrays (SMMs) have emerged as a powerful high-throughput screening platform that enables researchers to simultaneously profile thousands of distinct molecular interactions in a single experiment [17]. The success of this technology hinges on effective surface chemistry strategies that immobilize small molecules onto solid supports while preserving their biological activity. As a rapidly maturing technology, SMMs elegantly combine the capability of combinatorial chemistry to produce diverse compounds with the powerful throughput afforded by microarrays, providing scientists with a versatile tool for rapid compound analysis and discovery [17]. These platforms have been successfully applied to critical areas ranging from protein profiling to the discovery of therapeutic leads, making the optimization of immobilization chemistries a crucial aspect of chemical sensibilization research.

The fundamental challenge in SMM development lies in creating robust immobilization strategies that accommodate the diverse chemical structures found in small molecule libraries while maintaining consistent orientation and accessibility. Different immobilization chemistries offer distinct advantages and limitations regarding efficiency, specificity, and applicability to various compound classes. Among the most prominent strategies are isocyanate-based and maleimide-based immobilization platforms, each employing different mechanistic approaches to achieve covalent attachment of small molecules to functionalized surfaces. This application note examines these key immobilization platforms, provides detailed experimental protocols, and presents quantitative data to guide researchers in selecting appropriate surface chemistries for their specific SMM applications.

Core Immobilization Chemistries

Isocyanate-Based Immobilization

Isocyanate chemistry provides a versatile, non-selective immobilization strategy based on the reaction between surface-bound isocyanate groups and nucleophilic residues on target molecules. The electrophilic carbon of the isocyanate group reacts with various nucleophiles including primary amines, thiols, and alcohols to form stable covalent linkages [18]. The resonance structure of the isocyanate functional group significantly enhances the electrophilicity of the central carbon atom, driving its reactivity with diverse nucleophilic functional groups commonly found in small molecules [19].

A significant advantage of the isocyanate platform is its broad applicability across diverse compound libraries. Cheminformatic analyses predict that isocyanate-based chemistry is reactive with more than 25% of lead-like compounds in publicly available databases [20]. This broad reactivity profile makes it particularly valuable for immobilizing natural product libraries or other compound collections without common functional groups for selective attachment. The method enforces one-to-one stoichiometry through physical separation of reactants on the solid support, reducing the risk of multiple conjugations that could occlude binding sites [20].

Recent advancements in isocyanate-mediated chemical tagging (IMCT) have demonstrated the efficiency of this approach for appending chemical moieties to small molecules with enforced one-to-one stoichiometry [20]. This method utilizes a template resin with an isocyanate capture group and a cleavable linker, enabling modification of nucleophilic groups on small molecules including primary and secondary amines, thiols, phenols, benzyl alcohols, and primary alcohols [20]. The versatility of this platform has been further enhanced through the development of isocyanate-functionalized polymer microspheres, which provide high specific surface area and outstanding mechanical properties for catalytic and immobilization applications [21].

Maleimide-Based Immobilization

Maleimide chemistry offers a selective immobilization strategy based on the thiol-maleimide conjugation, which proceeds through a Michael addition mechanism [22]. This reaction involves the attack of a thiol group (commonly from a cysteine residue) on the electron-deficient double bond of the maleimide, forming a stable succinimidyl thioether linkage [23]. The reaction occurs rapidly under mild conditions, typically at neutral pH, making it suitable for labeling peptides, proteins, oligonucleotides, and small molecules [23].

The thiol-maleimide reaction is considered part of the 'click chemistry' toolbox due to its high efficiency, selectivity, and ability to proceed under mild conditions [22]. Despite not being a Huisgen-type click reaction, it shares the same modular, reliable qualities that make click reactions valuable in bioconjugation. The fast kinetics and straightforward application make it a preferred method for linking various biomolecules in research and pharmaceutical development [22].

A significant challenge in maleimide-thiol conjugation is the potential for side reactions, particularly when working with N-terminal cysteine peptides. The resulting succinimide is susceptible to nucleophilic attack from the N-terminal amine of the cysteine, leading to a thiazine impurity through a rearrangement reaction [22]. This side reaction can complicate purification, characterization, and storage of peptide conjugates, potentially leading to product loss. Research has demonstrated that performing conjugation under acidic conditions (near pH 5) or acetylating the N-terminal cysteine can prevent thiazine formation [22].

Comparative Analysis of Immobilization Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of Key Immobilization Platforms for Small Molecule Microarrays

| Platform | Reactive Groups | Immobilization Efficiency | Specificity | Stability | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isocyanate | Primary/Secondary amines, Thiols, Alcohols, Phenols | 73% overall immobilization rate [18] | Non-selective, broad reactivity | Urea, carbamate, thiocarbamate linkages | Diverse compound libraries, natural products |

| Maleimide | Thiols (cysteine residues) | High for thiol-containing compounds [23] | Highly specific for thiol groups | Succinimidyl thioether (susceptible to thiazine rearrangement) [22] | Thiolated molecules, controlled orientation |

| Epoxy | Amines, Thiols, Alcohols | Medium to high | Moderate specificity | Ether linkages | Carbohydrates, alcohols, amines |

| Streptavidin-Biotin | Biotin groups | Nearly quantitative | Highly specific | Non-covalent but very strong (Kd ~ 10⁻¹⁵ M) | Pre-biotinylated compounds |

Table 2: Nucleophilic Group Reactivity with Isocyanate Functionalized Surfaces

| Nucleophilic Group | Reactivity Classification | Relative Immobilization Efficiency | Resulting Linkage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary amine, Aryl amine, Thiol | High | >70% | Urea, Thiocarbamate |

| Primary alcohol, Phenol, Secondary amine | Medium | 30-70% | Carbamate, Urea |

| Carboxylic acid, Secondary alcohol, Tertiary alcohol | Low | <10% | Mixed anhydride, Carbamate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Isocyanate-Functionalized Slides and Small Molecule Immobilization

Principle: This protocol describes the preparation of isocyanate-functionalized glass slides and subsequent immobilization of small molecules containing nucleophilic functional groups, based on optimized conditions that achieve over 73% immobilization efficiency [18].

Materials:

- Amine-functionalized glass slides (CapitalBio Corporation)

- Fmoc-NH-(PEG)n-(CH2)2-COOH (n = 1, 2, 6, 12, 24, 36)

- (Benzotriazol-l-yloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP)

- N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA)

- Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) or 1,4-Phenylene diisocyanate (PPDI)

- Dimethylformamide (DMF), anhydrous

- Tetrahydrofuran (THF), anhydrous

- Piperidine

- Small molecule compounds dissolved in DMSO or DMSO/water mixtures

Procedure:

Spacer Arm Introduction:

- Prepare coupling solution containing 1 mM Fmoc-NH-(PEG)n-(CH2)2-COOH, 2 mM PyBOP, and 20 mM DIPEA in anhydrous DMF.

- Immerse amine-functionalized glass slides in the coupling solution for 10 hours with gentle stirring.

- Rinse slides thoroughly with fresh DMF to remove unreacted reagents.

Fmoc Deprotection:

- Prepare deprotection solution containing 1% (v/v) piperidine in DMF.

- Incubate PEG-treated glass slides in deprotection solution for 12 hours with gentle stirring.

- Rinse slides with DMF to completely remove piperidine and cleavage byproducts.

Isocyanate Functionalization:

- Prepare 60 mM isocyanate solution in DMF (for HDI) or THF (for PPDI).

- Incubate deprotected slides in isocyanate solution for 1 hour with stirring.

- Rinse functionalized slides thoroughly with DMF and THF.

- Dry slides under a stream of purified nitrogen.

- Store at -20°C if not used immediately.

Small Molecule Printing:

- Prepare small molecule solutions at concentrations of 1-10 mM in DMSO or DMSO/water mixtures (50:50 v/v).

- Print compounds onto isocyanate-functionalized slides using a contact microarray printer (e.g., SmartArrayer 136).

- Maintain spot diameter of 100-150 μm with center-to-center spacing of 250 μm.

- Include control compounds (e.g., baicalein, rapamycin, FK506) at 5 mM in DMSO.

Post-Printing Treatment:

- After printing, incubate slides under one of the following optimized conditions:

- 65°C for 2 hours in a humidified chamber

- Room temperature for 12 hours in a desiccator

- 37°C for 6 hours with controlled humidity

- Wash slides with DMSO followed by ethanol to remove unbound compounds.

- Dry slides by centrifugation or under nitrogen stream.

- After printing, incubate slides under one of the following optimized conditions:

Validation:

- Immobilization efficiency can be validated using fluorescently tagged compounds or through binding assays with target proteins.

- Optimal results are achieved with (PEG)12 spacers and HDI-derived isocyanate surfaces [18].

- The overall immobilization percentage should exceed 73% across diverse compound libraries.

Protocol: Maleimide-Thiol Conjugation for Directed Immobilization

Principle: This protocol describes the immobilization of thiol-containing small molecules onto maleimide-functionalized surfaces, utilizing the highly specific thiol-maleimide click chemistry [23].

Materials:

- Maleimide-functionalized slides (commercial sources or prepared from epoxy slides)

- Thiol-containing small molecules (or molecules modified with thiol groups)

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)

- Degassed phosphate buffer (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.0-7.5)

- Nitrogen or argon gas

- DMSO or DMF, anhydrous

Procedure:

Surface Preparation:

- Use commercial maleimide-functionalized slides or prepare by reacting epoxy slides with ethylenediamine followed by BMPS (N-β-maleimidopropionic acid hydroxysuccinimide ester).

- Verify maleimide functionality with thiol-containing fluorescent dyes.

Thiol Reduction (if necessary):

- Dissolve thiol-containing small molecules in degassed phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-7.5.

- Add 100× molar excess of TCEP relative to disulfide bonds.

- Flush with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature.

Immobilization Reaction:

- Apply reduced thiol-containing compounds to maleimide-functionalized surfaces.

- For compounds with poor aqueous solubility, include organic co-solvent (DMSO or DMF, not exceeding 20% v/v).

- Incubate overnight at 4°C or for 4 hours at room temperature in an inert atmosphere.

Quenching and Washing:

- Quench unreacted maleimide groups with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 30 minutes.

- Wash slides extensively with buffer containing mild detergent followed by water.

- Dry slides by centrifugation.

Critical Considerations:

- To prevent thiazine side reactions with N-terminal cysteine peptides, perform conjugation at pH 5 or acetylate the N-terminal amine [22].

- For maleimides with poor aqueous solubility, increase organic co-solvent content gradually to avoid precipitation.

- Avoid oxygen exposure throughout the procedure to prevent disulfide formation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Immobilization Platforms

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) | Bifunctional crosslinker for isocyanate surface functionalization | Provides flexible 6-carbon spacer; use at 60 mM in DMF for optimal results [18] |

| Fmoc-NH-PEGn-COOH | Spacer arm with protected amine | Varying lengths (n=1-36) adjust distance from surface; (PEG)12 recommended [18] |

| PyBOP | Coupling reagent for carboxylate activation | Efficiently activates spacer arm carboxyl groups for amine coupling [18] |

| Maleimide-PEG-NHS | Heterobifunctional crosslinker | NHS ester reacts with surface amines, maleimide for thiol conjugation [23] |

| TCEP | Reducing agent for disulfide bonds | Use 100× molar excess; preferred over DTT as it doesn't contain thiols [23] |

| Biotin-PEGn-NH₂ | Positive control for immobilization | Quality control with streptavidin detection; various PEG lengths available [18] |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The application of advanced immobilization platforms extends beyond conventional small molecule screening. Recent innovations include the development of ArrayPlex spot-on-spot microarrays that enable the creation of multi-layered microarrays, allowing two libraries to be screened against each other with unprecedented throughput [24]. This technology generates millions of data points each week, dramatically accelerating the discovery process.

Isocyanate-based multicomponent reactions represent another emerging application, enabling the efficient synthesis of structurally diverse and complex molecules [19]. These one-pot reactions incorporate more than two reactants into a single final product, providing access to complex molecular architectures with high molecular diversity. The added benefit of isocyanate-based MCRs includes their atom-economical nature and alignment with green chemistry principles, making them environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional synthetic approaches [19].

In maleimide chemistry, recent advances have focused on the transformation of maleimides via annulation reactions, forming cyclized molecules through annulation and C-H activation [25]. These methodologies have enabled the efficient synthesis of various cyclized products, including annulation, benzannulation, cycloaddition, and spirocyclization, with applications in medicinal chemistry, drug discovery, and materials science. Photocatalysis and electrochemical methods have further expanded the utility of maleimides, providing more sustainable and selective approaches for synthesizing complex molecules [25].

Comparative studies between maleimide-thiol conjugation and click chemistry approaches have revealed advantages of each system. While maleimide-thiol conjugation offers rapid reaction kinetics, click chemistry provides superior control over stoichiometry and produces more defined conjugates [26]. The choice between these strategies depends on the specific application requirements, including the need for controlled stoichiometry, orientation preservation, and functional binding capacity.

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflow for SMM Immobilization Platforms. This diagram illustrates the parallel pathways for preparing isocyanate-based and maleimide-based small molecule microarrays, highlighting key steps in each immobilization strategy.

Diagram 2: Isocyanate Reactivity Profile with Nucleophilic Functional Groups. This diagram visualizes the relative reactivity of various nucleophilic functional groups with isocyanate surfaces, categorized by high (green), medium (yellow), and low (red) reactivity classes based on experimental data [18].

The fields of combinatorial chemistry and DNA microarray technology originated from parallel paths in the late 1980s and early 1990s, driven by a common goal: the high-throughput analysis of vast molecular libraries [27] [28]. This convergence created the foundation for small molecule microarray (SMM) technology, a powerful tool for modern drug discovery. SMMs synergize the core principle of combinatorial chemistry—the systematic synthesis of large compound libraries—with the spatial addressing and multiplexing capabilities of microarray platforms [17] [24]. This article details the historical application notes and experimental protocols that emerged from this technological fusion, providing a framework for sensitizing chemical libraries for high-throughput screening.

Historical Application Notes

The convergence was not accidental; it was driven by a pressing need in biomedical research to functionally examine the proteome at a global level [27]. The following applications were pivotal.

From Peptide Libraries to Small Molecule Screening

Combinatorial chemistry was first applied to generate peptide arrays in 1984 [27]. Early work by Geysen's multi-pin technology and Houghten's tea-bag method enabled the parallel synthesis of hundreds of thousands of peptides on a solid support [29]. The critical evolution was the shift from peptides to diverse small molecules. In 1992, Bunin and Ellman reported the first small-molecule combinatorial library, demonstrating the technology's applicability beyond biological polymers [29]. This expansion of chemical space was a prerequisite for populating SMMs with pharmacologically relevant compounds.

The Adoption of Microarray Instrumentation

A key step in the convergence was the repurposing of instrumentation and solid-support methods originally developed for DNA microarrays [27] [28]. The use of fully automatic arrayers and in-situ synthesis on glass slides allowed combinatorial libraries to be spatially addressed at high density [27]. This transformed libraries from mixed collections in a single vial to ordered, position-addressable arrays, enabling direct and simultaneous screening of thousands of compounds.

Key Application: Lead Identification and Optimization

The primary application of this converged technology has been in the identification and optimization of drug leads. The one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) combinatorial library method, when paired with microarray screening, proved highly effective [27] [29]. SMMs provided a "versatile tool for rapid compound analysis and discovery" in areas ranging from protein profiling to the discovery of therapeutic leads [17]. The technology allows for the rapid determination of structure-activity relationships (SAR) by screening entire families of related compounds in a single experiment.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Key Combinatorial and Microarray Technologies

| Technology | Approximate Emergence | Key Innovation | Impact on SMM Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis | 1960s (Merrifield) | Enabled step-wise synthesis on an insoluble polymer support [30]. | Provided the foundational synthetic methodology. |

| Geysen's Multi-pin Technology | Mid-1980s | Parallel synthesis of peptides on polypropylene pins [29] [28]. | First step towards spatial arraying of combinatorial libraries. |

| Split-Pool Synthesis ("Tea-Bag") | Mid-1980s | Generation of highly diverse compound mixtures [29]. | Enabled creation of large, diverse libraries for SMMs. |

| Affymetrix GeneChip (VLSIPS) | Early 1990s | Light-directed, spatially-addressable parallel synthesis on a chip [28]. | Proved concept of high-density chemical synthesis on a solid surface. |

| One-Bead-One-Compound (OBOC) | 1991 (Lam et al.) | Coupled split-pool synthesis with single compound isolation on beads [29]. | Bridged solution-based combinatorial chemistry with solid-phase screening. |

| Printed Small Molecule Microarrays | Early 2000s | Robotic printing of pre-synthesized compounds onto functionalized slides [27] [17]. | Created the modern, accessible SMM platform. |

Quantitative Performance of SMM Platforms

The technological convergence yielded platforms with exceptional throughput and sensitivity, as evidenced by historical performance data from commercial systems.

Table 2: Representative SMM Platform Performance Metrics (c. 2000s)

| Platform / Method | Library Diversity | Screening Throughput | Typical Spot Density (spots/slide) | Required Sample Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Situ Synthesized Arrays | ~100,000 compounds [27] | ~1 assay per library | >10,000 [27] | N/A (synthesized on slide) |

| Printed SMMs (e.g., Arrayjet) | 10,000 - 18,400 compounds [24] | ~1 assay per library | 1,000 - 10,000 [24] | 0.5 µL samples can print ~1,000 slides [24] |

| One-Bead-One-Compound (OBOC) | Millions to billions [29] | ~1 assay per library | N/A (bead-based) | N/A (bead-based) |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DEL) | >1 million compounds [29] | ~1 assay per library | N/A (solution-based) | N/A (solution-based) |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for creating and screening small molecule microarrays, reflecting the standardized protocols that resulted from the convergence of these fields.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Small Molecule Microarray via Contact Printing

This protocol outlines the creation of an SMM by printing pre-synthesized compounds from a combinatorial library onto a functionalized glass slide.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SMM Fabrication and Screening

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Glass Slides | Solid support with chemical groups (e.g., isocyanate, epoxy) for covalent immobilization of small molecules [24]. |

| Combinatorial Compound Library | A diverse collection of small molecules, typically in 384-well plates, dissolved in appropriate solvent (e.g., DMSO) [24]. |

| Microarray Spotter | Robotic instrument (e.g., contact pin or inkjet) for transferring nanoliter volumes of compound solution to the slide surface [27] [24]. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution (e.g., containing BSA) used to passivate the slide surface after printing to prevent non-specific binding [24]. |

| Fluorescently-Labeled Protein Target | The protein of interest (e.g., kinase, receptor) is conjugated to a fluorophore (e.g., Cy3, Cy5) for detection [24]. |

| Microarray Scanner | A fluorescence-based scanner used to detect and quantify binding events on the microarray surface [31]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Library Preparation: Prepare the compound library in 384-well plates. Compounds are typically dissolved in DMSO at a concentration suitable for printing and immobilization (e.g., 1-10 mM) [24].

- Slide Activation: Prior to printing, ensure the functionalized slides (e.g., isocyanate-coated) are clean, dry, and at the appropriate relative humidity within the printing environment (typically controlled at 40-60%) [24].

- Array Printing: Program the microarray spotter with the desired layout. Load the source microplates and destination slides. The instrument will transfer compounds from the wells to designated locations on the slide. For example, the Arrayjet Mercury system uses a non-contact inkjet to dispense spots as small as 40 pL [24].

- Immobilization and Quenching: After printing, incubate the slides in a humidified chamber for 4-16 hours to allow for complete covalent coupling of the compounds to the slide surface. Quench any remaining active groups by immersing the slides in a blocking buffer (e.g., 50 mM ethanolamine, 0.1% SDS in Borate buffer) for 1 hour.

- Washing and Drying: Wash the slides sequentially in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), deionized water, and isopropanol to remove unbound compounds and salts. Dry the slides by centrifugation or under a stream of inert gas. The slides can be stored desiccated and in the dark until use.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the SMM fabrication process:

Protocol 2: Screening a Small Molecule Microarray for Protein Binding

This protocol describes how to probe a fabricated SMM with a fluorescently labeled protein to identify binding interactions.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Target Preparation: Dilute the fluorescently-labeled protein target to an appropriate concentration (e.g., 1-10 µg/mL) in a binding buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20). The inclusion of a carrier protein and detergent helps minimize non-specific binding.

- Probe Hybridization: Apply the protein solution to the surface of the SMM under a coverslip or within a sealed hybridization chamber. Incubate the slide in a dark, humidified chamber for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 4°C to allow for binding.

- Stringency Washes: Gently remove the coverslip and wash the slide three times (5 minutes per wash) with binding buffer (without the protein) to remove unbound and weakly bound protein.

- Rinse and Dry: Perform a final brief rinse in deionized water to remove buffer salts. Dry the slide by centrifugation.

- Signal Acquisition: Scan the slide immediately using a microarray scanner configured for the appropriate fluorescence channel (e.g., Cy3 or Cy5). Set the laser power and photomultiplier tube (PMT) gain to avoid signal saturation.

- Hit Identification: Analyze the resulting fluorescence image using microarray analysis software. Positive hits are identified as spots with a fluorescence signal significantly above the local background. The signal intensity correlates with the amount of bound target [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the SMM screening process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials essential for work in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SMM Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Slides (Isocyanate/Epoxy) | Provide a reactive surface for the covalent immobilization of small molecules bearing amino or hydroxyl groups, ensuring stable attachment during assays [24]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (Cy3, Cy5) | Used to label protein or other biological targets, enabling detection and quantification of binding interactions on the microarray [31] [32]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Ethanolamine) | Used to passivate the slide surface after printing, reducing non-specific adsorption of the protein target and minimizing background noise [24]. |

| DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries (DECLs) | Combinatorial libraries where each small molecule is tagged with a unique DNA barcode, allowing for pooled screening and hit deconvolution via PCR and sequencing [29]. |

| OBOC Library Beads | Solid support microbeads, each displaying a single compound from a combinatorial library, enabling screening of millions of compounds and subsequent chemical decoding [29]. |

| Automatic Arrayer/Microarray Spotter | Robotic instrument capable of transferring nanoliter volumes of compound solutions from multi-well plates to microscope slides with high precision and spatial density [27] [24]. |

SMMs in Action: Methodological Workflows and Cutting-Edge Applications from Proteins to RNA

Small molecule microarrays (SMMs) have emerged as a powerful, high-throughput platform for probing interactions between vast collections of small molecules and biological targets of interest. This technology is particularly valuable in drug discovery and chemical biology for identifying lead compounds that bind to proteins and, more recently, RNA targets [33] [5]. The core principle involves spatially arraying and immobilizing thousands of small molecules on a solid support, incubating the array with a labeled target, and detecting binding events to identify specific ligands. The miniaturized and parallel nature of SMMs allows for the rapid screening of tens of thousands of compounds against one or multiple targets simultaneously, providing critical information on both binding affinity and selectivity [33] [1]. This application note details a robust, end-to-end protocol for SMM fabrication using isocyanate-based covalent immobilization, followed by target incubation and data analysis, framed within research aimed at enhancing the sensitivity and reliability of these platforms.

The SMM screening process is fundamentally a binding assay that enables the discovery of ligands for targets without prior knowledge of their structure or function [5]. A diverse library of small molecules is printed and covalently attached to a functionalized glass slide. The resulting microarray is then probed with a purified, fluorescently labeled target or a lysate containing an epitope-tagged or endogenous target, which is detected via a fluorescent antibody. After washing, the slide is imaged with a fluorescence scanner, and statistical analysis identifies spots with significantly increased fluorescence, correlating to specific molecular interactions [33] [5] [1]. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, from slide preparation to hit identification.

Materials and Reagents: The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents required for the successful execution of the SMM workflow.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for SMM Fabrication and Screening

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| GAPS II Coated Glass Slides | Solid support for microarray fabrication. | Amine-functionalized surface for subsequent chemistry [33]. |

| 1,6-diisocyanatohexane (HDI) | Creates isocyanate-functionalized surface for covalent compound immobilization. | Reacts with nucleophilic groups on small molecules [33] [18]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Spacers | Penultimate group between slide surface and isocyanate; acts as a spacer. | Longer spacers (e.g., n=12) can improve immobilization efficiency and target access [18]. |

| Small Molecule Library | Source of chemical diversity for screening. | Ideally, a diverse collection of ~20,000 drug-like compounds with nucleophilic handles (amines, alcohols) [33] [34]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Solvent for small molecule stock solutions. | High-quality, anhydrous DMSO is critical for compound stability and print quality [33]. |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Hydrazide | Fluorescent dye for labeling the RNA or protein target. | Enables detection of binding events upon slide scanning [33]. |

| PyBOP, DIPEA | Peptide coupling reagents. | Used for coupling the PEG spacer to the amine-coated slide [33] [18]. |

| RNase-free PBS with Tween 20 (PBST) | Wash buffer for post-incubation steps. | Removes unbound target; Tween-20 reduces non-specific binding [33]. |

| Quench Solution (Ethylene glycol, Pyridine) | Post-printing treatment. | Deactivates unreacted isocyanate groups on the slide surface [33]. |

Experimental Protocols

Preparation of Isocyanate-Coated Slides

The functionalization of the slide surface is a critical first step to ensure efficient and uniform compound immobilization [18].

- PEG Spacer Coupling: Immerse amine-functionalized glass slides in a coupling solution containing 1 mM Fmoc-protected PEG-acid (e.g., Fmoc-NH-(PEG)~12~-COOH), 2 mM PyBOP, and 20 mM DIPEA in DMF. Incubate for 10 hours with stirring [18].

- Fmoc Deprotection: Remove the Fmoc protecting group by incubating the slides in a solution of 1% (v/v) piperidine in DMF for 12 hours with gentle stirring. This exposes the primary amine terminus of the PEG spacer [33] [18].

- Isocyanate Activation: Incubate the deprotected slides in a 1% (v/v) solution of 1,6-diisocyanatohexane (HDI) in DMF for 1 hour with stirring. This step introduces the terminal isocyanate groups that will react with printed compounds. Rinse slides thoroughly with DMF and tetrahydrofuran (THF), and dry with a stream of nitrogen or canned air. Store functionalized slides at -20°C if not used immediately [33].

Small Molecule Library and Source Plate Preparation

The composition of the small molecule library is key to a successful screen.

- Library Composition: Acquire a diverse library of drug-like compounds. An ideal library has an average molecular weight near 400 Da, uses a structural diversity filter (e.g., Tanimoto cutoff <0.8), and is filtered to minimize pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) [33]. Compounds must contain nucleophilic functional groups for immobilization (e.g., amines, alcohols).

- Source Plates: Prepare compound source plates as 10 mM stocks in DMSO in 384-well V-bottom plates. Include control compounds (e.g., biotin-PEG-amine for detection with streptavidin-fluorophore) in separate wells. Seal plates with thermal seals to prevent evaporation [33].

Printing of Small Molecule Microarrays

This protocol is based on using a contact microarray printer with 48 pins.

- Setup: Load the compound source plates and isocyanate-coated slides into the microarray printer. Use a controlled environment (low humidity) to optimize spot morphology.

- Printing: Program the printer to deposit nanoliter volumes of each compound onto the slides in a predefined pattern. A typical configuration prints 3840 compounds in duplicate across 48 subarrays per slide, allowing a library of >22,000 compounds to be printed on just six slides [33].

- Post-Printing Treatment: After printing, place slides in a vacuum desiccator with a vial of anhydrous pyridine for 12-16 hours. The vapor facilitates the covalent coupling reaction between the compounds and the isocyanate surface. Subsequently, quench any remaining isocyanate groups by immersing the slides in a solution of 5% (v/v) ethylene glycol and 0.1% (v/v) pyridine in DMF for 1 hour [33] [18].

- Storage: Wash the printed and quenched microarrays with DMF and THF, dry, and store in a desiccator at room temperature until use.

Target Incubation and Detection

This section outlines the protocol for screening with a fluorescently labeled RNA target.

- Preparation: Decontaminate the work area with RNase AWAY or a similar reagent. Use nuclease-free water and buffers.

- Hybridization (Incubation): Dilute the Alexa Fluor 647-labeled RNA target in RNase-free PBS to the desired concentration (e.g., 1-500 nM). Apply the solution to the microarray under a coverslip or in a multi-well incubation dish. Incubate the slide in a humidified, dark chamber for 30-60 minutes at room temperature to allow binding interactions to occur [33].

- Washing: Remove the coverslip and wash the slide three times with RNase-free PBST (PBS with 0.01% Tween 20) to remove unbound RNA, followed by a final rinse with nuclease-free water. Dry the slides by centrifugation in a 50 mL Falcon tube (5 minutes at 500 rpm) [33].

- Control Staining: To confirm successful printing and immobilization, the array can be stained with a solution of Streptavidin-FITC (for biotinylated controls) after the RNA incubation and wash steps.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Scanning: Image the dried microarray slides using a fluorescence microarray scanner. Scan at multiple wavelengths to detect the fluorescent signal from the bound RNA target (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647) and the control compounds (e.g., FITC) [33].

- Image and Data Analysis: Use array imaging software (e.g., GenePix Pro, Mapix) to align the grid, quantify the fluorescence intensity of each spot, and subtract the local background.

- Hit Identification: Perform statistical analysis to identify significant outliers. A common method is to normalize the data (e.g., using Z-scores) and flag spots whose intensity exceeds the mean signal of the entire array by a predetermined number of standard deviations (e.g., Z-score > 3) [33]. Comparing signals from the target channel to the control channel helps eliminate printing artifacts.

Results and Data Interpretation

Optimization and Performance Data

The efficiency of small molecule immobilization is highly dependent on the nucleophilic residue present and the surface chemistry conditions. The following table summarizes quantitative data on immobilization efficiency, which is crucial for evaluating and optimizing the SMM platform.

Table 2: Immobilization Efficiency of Small Molecules on Isocyanate Surfaces Under Optimized Conditions [18]

| Factor Evaluated | Condition / Nucleophile | Key Finding / Efficiency | Implication for Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleophile Reactivity | Primary Amine | High (Benchmark) | Library should be enriched with high-reactivity groups. |

| Carboxylic Acid | Low (<10% of amine) [18] | Optimization critical for these compounds. | |

| Spacer Length (PEG~n~) | n=1 (short) | Lower efficiency | Use longer spacers (e.g., n=12) to improve efficiency and target access [18]. |

| n=12 (long) | Significantly improved efficiency [18] | ||

| Penultimate Group | Hexyl (from HDI) | Improved morphology & efficiency [18] | Use 1,6-diisocyanatohexane (HDI) for slide preparation. |

| Phenyl (from PPDI) | Lower efficiency [18] | ||

| Post-Print Treatment | Pyridine Vapor | >73% overall immobilization [18] | Essential protocol step for high-density immobilization. |

| Overall Performance | Optimized Protocol | >73% of 3375 compounds immobilized [18] | Validates the robustness of the described workflow. |

Discussion

The integrated workflow described herein provides a reliable path for identifying small molecule ligands for biological targets using SMMs. The use of isocyanate chemistry offers a key advantage: the ability to immobilize a wide range of compounds without pre-derivatization, enabling the screening of diverse libraries including bioactive molecules, natural products, and synthetic compounds on a single platform [1] [34]. A critical insight from optimization studies is that the immobilization efficiency for molecules with low-reactivity nucleophiles (e.g., carboxylic acids) can be drastically improved by using longer PEG spacers and optimized post-printing treatments, ultimately leading to a more representative screening of the entire library [18].