Privileged Structures in Chemical Biology: From Foundational Scaffolds to Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of privileged structures—molecular scaffolds with versatile binding properties to multiple biological targets.

Privileged Structures in Chemical Biology: From Foundational Scaffolds to Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of privileged structures—molecular scaffolds with versatile binding properties to multiple biological targets. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational definition and historical context of these motifs, their application in focused library design and phenotypic screening, and modern strategies to overcome challenges like polypharmacology and poor solubility. It further examines advanced validation techniques, including AI-driven structural modification and proteomic profiling, synthesizing key takeaways to outline future directions for leveraging privileged scaffolds in developing novel therapeutics against evolving biological targets.

What Are Privileged Structures? Defining the Cornerstones of Chemical Biology

The concept of "privileged structures" represents a cornerstone principle in modern medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. First coined by Benjamin Evans and colleagues in 1988, this paradigm identifies molecular scaffolds with an inherent ability to bind to multiple, structurally diverse biological targets. This whitepaper traces the origin, conceptual evolution, and contemporary applications of the privileged structure concept, documenting its development from a seminal observation to a systematic framework for rational drug design. The discussion is framed within the broader context of chemical biology research, highlighting how this approach has addressed fundamental challenges in ligand discovery and library design. By examining quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and emerging trends, this analysis demonstrates why the Evans definition remains a vital tool for researchers seeking to efficiently navigate chemical space and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic agents.

The fundamental challenge in drug discovery lies in identifying or designing small organic molecules that can specifically and potently modulate biological targets. Despite significant advances in synthetic chemistry and screening technologies, the discovery of high-quality lead compounds remains resource-intensive, with traditional high-throughput screening often yielding disappointingly low hit rates [1]. Commercial compound libraries frequently suffer from limited structural diversity and suboptimal physicochemical properties, while natural product-derived collections, though often bioactive, may not readily yield novel specificities through simple structural modification [1].

In this challenging landscape, the concept of "privileged structures" emerged as a powerful heuristic to improve the efficiency of ligand discovery. This approach does not seek entirely novel chemotypes de novo but instead builds upon molecular frameworks with empirically demonstrated versatility. The core premise is that certain structural motifs possess intrinsic geometric and electronic properties that favor interactions with a range of biological macromolecules, making them particularly valuable starting points for library design and lead optimization.

The Evans Origin: A Seminal Observation

Historical Context and Original Definition

The term "privileged structure" was formally introduced into the medicinal chemistry lexicon by Benjamin Evans and colleagues at Merck in their 1988 study on the development of cholecystokinin (CCK) antagonists [2] [3] [1]. In this seminal work, they observed that benzodiazepine and substituted indole scaffolds repeatedly appeared in compounds exhibiting affinity for multiple, unrelated receptor systems.

Evans' original conception defined privileged structures as "molecular scaffolds with versatile binding properties," such that a single framework could yield potent and selective ligands for diverse biological targets through strategic modification of functional groups [4] [5]. This was not merely an observation of promiscuous binding but an recognition of scaffolds that could be deliberately functionalized to achieve selectivity for specific targets.

The Original Experimental Evidence

The experimental foundation for Evans' conclusion came from work on benzodiazepines, which were known primarily as central nervous system agents targeting GABA_A receptors. His team discovered that structural elaboration of this core could generate high-affinity antagonists for peptide receptors like CCK, entirely distinct from their original neurological targets [2] [1]. This demonstrated that the benzodiazepine nucleus served as a versatile template capable of addressing different receptor families.

The significance of this observation lay in its suggestion that privileged structures might structurally mimic common protein recognition elements, with the benzodiazepine scaffold thought to mimic beta-turn peptides [1]. This provided a potential structural basis for their broad recognition across different protein classes.

Conceptual Evolution and Refinement

From Empirical Observation to Systematic Principle

Following Evans' initial identification, the privileged structure concept evolved from an empirical observation to a systematic guiding principle in library design. Klaus Mueller later refined the definition, specifying privileged structures as "small, non-planar structures with robust conformations that provide interesting 3D exit vectors for substitution, with drug-like properties and ideally readily accessible synthetically" [2].

This refinement emphasized several key characteristics:

- Semi-rigidity: Possessing sufficient flexibility to adapt to binding sites while maintaining a preferred conformation

- Robust substitution vectors: Providing multiple points for synthetic modification to explore chemical space

- Drug-like properties: Inherent physicochemical characteristics compatible with bioavailability

The conceptual evolution expanded the application of privileged structures beyond GPCRs (their original domain) to include enzymes, ion channels, and other target classes [5].

Distinguishing Privileged Structures from PAINS

A critical development in the evolution of the privileged structure concept has been its distinction from Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS). While both may exhibit activity across multiple assays, privileged structures achieve this through specific, drug-like interactions with biological targets, whereas PAINS often operate through non-specific mechanisms like covalent modification, aggregation, or fluorescence interference [6].

This distinction is crucial for proper application in drug discovery. Researchers must carefully evaluate potential privileged scaffolds against known PAINS filters and confirm activity through multiple assay types to avoid false positives [6]. This discernment has helped preserve the utility of the privileged structure concept against concerns about promiscuous binders.

Quantitative Landscape of Privileged Structure Research

The growing impact of privileged structures in chemical biology and drug discovery is evidenced by quantitative metrics from the scientific literature. The systematic application of this approach has yielded a rich landscape of scaffolds with demonstrated utility across target families.

Table 1: Bibliometric Analysis of Privileged Structure Research

| Metric | Data | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science Records | 6,285 records | As of 2021 [6] |

| Exemplary Scaffolds | Benzodiazepines, indoles, biphenyls, diaryl ethers, piperidines, piperazines, purines, spiropiperidines, N-acylhydrazones | Comprehensive literature survey [4] [6] [3] |

| Therapeutic Areas | Antivirals, CNS disorders, oncology, infectious diseases, inflammation | Post-2009 literature [6] |

Table 2: Privileged Structures in Approved Drugs and Clinical Candidates

| Scaffold | Example Drugs | Therapeutic Applications | Molecular Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | Diazepam, Clobazam | Anxiolytics, anticonvulsants | GABA_A receptor [3] |

| Diaryl Ether | Roxadustat, Ibrutinib, Sorafenib | Anemia, cancer, cancer | HIF-PH inhibitor, BTK inhibitor, kinase inhibitor [6] |

| Beta-Lactam | Penicillin, Imipenem | Antibacterial | Cell wall synthesis [3] |

| Piperazine | Ciprofloxacin, Sildenafil | Antibacterial, erectile dysfunction | DNA gyrase, PDE5 [3] |

| Purine | 6-Mercaptopurine | Cancer, immunomodulation | Nucleic acid synthesis [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Privileged Structure Identification and Validation

The effective utilization of privileged structures in chemical biology research requires rigorous experimental approaches for their identification, validation, and optimization.

Protocol 1: Library Design and Synthesis from Privileged Scaffolds

Objective: To create a focused compound collection based on a privileged scaffold with maximum structural diversity and drug-like properties.

Methodology:

- Scaffold Selection: Identify candidate privileged structures through literature mining of multi-target scaffolds or analysis of structural motifs recurring in drugs against different targets [1].

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Plan synthetic routes amenable to solid-phase or solution-phase parallel synthesis, identifying points of diversification [1].

- Library Construction: Employ split-pool or array-based synthesis to systematically introduce structural variation. The Ellman benzodiazepine library exemplifies this approach, utilizing 2-aminobenzophenones, amino acids, and alkylating agents to generate 192 members with 4 points of diversity [1].

- Characterization: Ensure comprehensive analytical characterization (LCMS, NMR) of all library members to verify purity and structure.

- Drug-likeness Assessment: Calculate physicochemical parameters (molecular weight, logP, H-bond donors/acceptors) to ensure adherence to drug-like space.

Protocol 2: Biological Evaluation and Hit Validation

Objective: To identify specific ligands from a privileged scaffold library while excluding non-specific binders or PAINS.

Methodology:

- Primary Screening: Screen library against multiple biologically relevant targets using biochemical or cell-based assays.

- Hit Confirmation: Apply secondary assays with orthogonal detection methods to validate initial hits [6].

- Counter-screening: Test against known PAINS filters and perform interference assays (e.g., detergent sensitivity, redox activity) to exclude false positives [6].

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: Systematically modify hit structures to establish SAR and guide optimization toward specific targets [3] [5].

- Target Engagement Studies: Use biophysical methods (SPR, ITC, X-ray crystallography) to confirm direct, specific binding to the intended target [6].

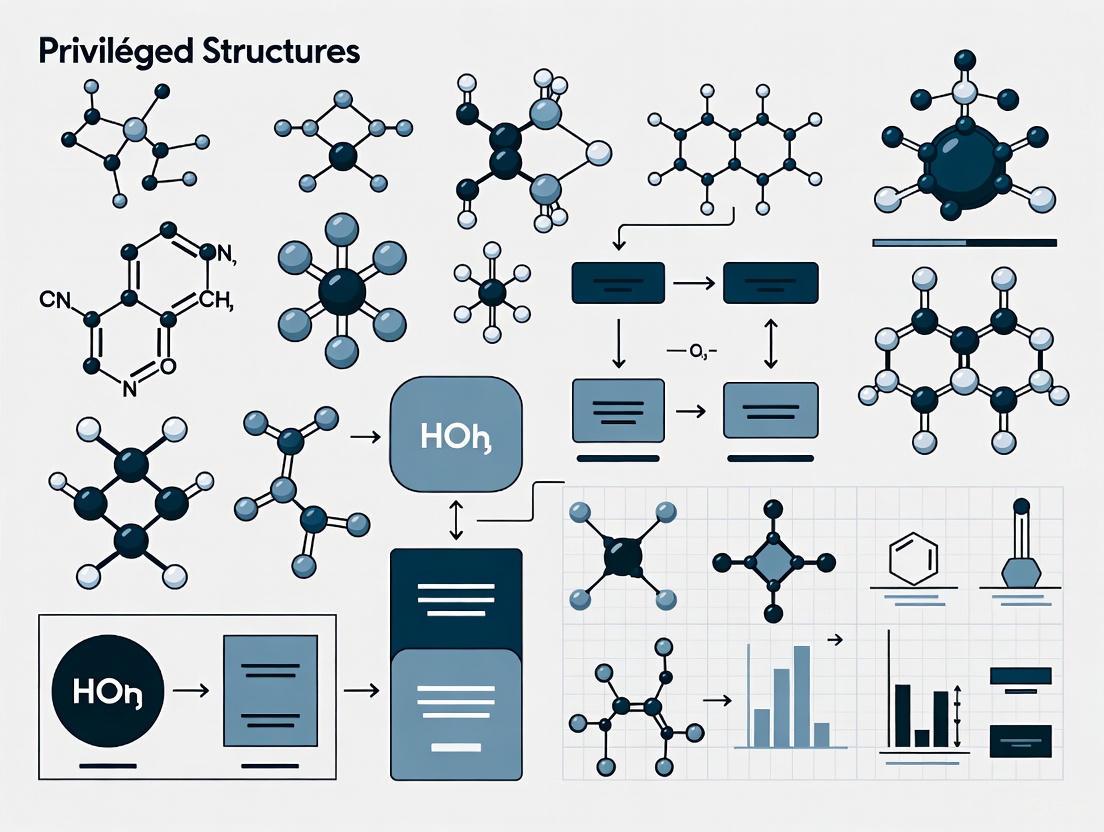

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for privileged structure research:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The experimental implementation of privileged structure-based research requires specific reagents, tools, and methodologies. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for working with privileged structures.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Privileged Structure Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Aminobenzophenones | Building blocks for benzodiazepine synthesis | Solid-phase synthesis of 1,4-benzodiazepine libraries [1] |

| Amino Acids | Introduce structural diversity & chirality | Provide R-group variation in scaffold libraries [1] |

| Alkylating Agents | Introduce additional diversity elements | N- or O-alkylation to explore steric and electronic effects [1] |

| Solid Supports | Enable parallel synthesis and purification | Geysen's Pin method or resin-based combinatorial synthesis [1] |

| PAINS Filters | Computational filters to exclude promiscuous compounds | Counter-screening to distinguish true privileged structures [6] |

| X-ray Crystallography | Determine ligand-target complexes | Structural biology to understand binding modes [6] |

| NMR-based Screening | Identify binding interactions in solution | Ligand-observed or protein-observed NMR screening [1] |

Case Study: Diaryl Ether as a Modern Privileged Structure

The diaryl ether (DE) scaffold exemplifies the continued relevance and application of the privileged structure concept in contemporary drug discovery. This motif features two aromatic rings connected by a flexible oxygen bridge, conferring favorable hydrophobic properties and metabolic stability [6].

Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Applications

In antiviral research, DE-based compounds have yielded critical therapeutic agents:

- Etravirine and Doravirine: FDA-approved HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors that maintain efficacy against mutant viral strains [6].

- Compound 3 (Bollini et al.): Exhibited extraordinary potency (EC~50~ = 55 pM) against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase through π-stacking interactions with tyrosine residues [6].

- Compound 11 (Chan et al.): Incorporated an acrylamide warhead for irreversible inhibition of HIV reverse transcriptase, demonstrating a novel strategy to counter drug resistance [6].

The following diagram illustrates the structure-activity relationship of diaryl ether-based antivirals:

More than three decades after its initial formulation by Evans, the privileged structure concept continues to evolve and demonstrate significant value in chemical biology and drug discovery. The original insight—that certain molecular frameworks possess inherent versatility across target families—has matured into a sophisticated approach for navigating chemical space and addressing the perennial challenge of low hit rates in screening.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas:

- Computational Identification: Enhanced algorithms for predicting new privileged scaffolds from chemical and bioactivity databases

- Structural Understanding: Deeper mechanistic insights into why certain scaffolds interact successfully with multiple targets

- Hybrid Approaches: Integration of privileged structures with other strategies like fragment-based drug design

- Accessibility: Continued development of synthetic methodologies to efficiently access underexplored privileged scaffolds

The enduring legacy of the Evans definition lies in its powerful synthesis of empiricism and rational design, providing researchers with a practical framework for prioritizing molecular starting points. As chemical biology continues to confront the complexity of biological systems, this conceptual tool remains essential for the systematic discovery of chemical probes and therapeutics.

Within the discipline of medicinal chemistry, the "privileged scaffold" concept, first coined by Evans and colleagues in 1988, has emerged as a powerful paradigm for accelerating the discovery of novel bioactive molecules [7] [1] [8]. These structures are defined as molecular frameworks capable of binding to multiple, often unrelated, biological targets with high affinity [5] [3]. This versatility stems from their innate ability to interact with diverse protein binding sites, making them exceptionally valuable as starting points for drug design [7]. Beyond their versatile binding properties, privileged scaffolds typically exhibit favorable drug-like characteristics, such as good chemical stability and pharmacokinetic profiles, which streamline the optimization process and increase the likelihood of developing viable clinical candidates [8] [3]. This whitepaper details the defining hallmarks of privileged scaffolds, the experimental methodologies for their identification and exploitation, and their integral role within modern chemical biology and drug discovery research.

Core Structural and Functional Hallmarks

The "privileged" status of a molecular scaffold is conferred by a combination of distinct structural and functional properties that enable its broad utility in drug discovery.

Table 1: Key Hallmarks of Privileged Scaffolds

| Hallmark | Description | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Versatile Binding Capacity | A single scaffold can provide high-affinity ligands for diverse biological targets (e.g., GPCRs, kinases, viral enzymes) through functional group modifications [7] [5]. | Increases hit rates in screening campaigns; provides a solid foundation for lead optimization across multiple target families [7] [5]. |

| Inherent Drug-like Properties | Scaffolds often possess good physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, polarity) that align with established rules for oral bioavailability and metabolic stability [8] [3]. | Leads to more drug-like compound libraries and candidates, reducing attrition in later development stages due to poor pharmacokinetics [8]. |

| Structural Mimicry | Many privileged scaffolds, such as benzodiazepines and 1,4-pyrazolodiazepin-8-ones, can mimic secondary protein structures like β-turns, facilitating interaction with protein surfaces [7] [1]. | Enables disruption of protein-protein interactions and targeting of a wider range of biological mechanisms [7]. |

| High Derivative Potential | The scaffolds are amenable to extensive and diverse chemical modification at multiple sites, allowing for fine-tuning of potency, selectivity, and properties [7] [3]. | Facilitates comprehensive Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies and the generation of large, focused libraries from a single core [7]. |

Experimental Workflows for Identification and Validation

The discovery and application of privileged scaffolds follow a systematic, iterative process that integrates chemical synthesis, biological screening, and computational analysis. The following workflow and detailed protocols outline this approach.

Diagram 1: Scaffold Discovery Workflow.

Protocol 1: Focused Library Synthesis via Solid-Phase Chemistry

This protocol, exemplified by the seminal work of Ellman and colleagues on 1,4-benzodiazepines, outlines the synthesis of a focused library around a privileged scaffold [7] [1].

- Objective: To efficiently generate a diverse collection of compounds based on a single privileged scaffold for biological evaluation.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Solid Support: Geysen's Pin apparatus or similar solid-phase resin with an acid-cleavable linker [7].

- Building Blocks: 2-aminobenzophenones (attached to solid support), diverse amino acids, and alkylating agents to introduce variability [7] [1].

- Scaffold Core: The privileged structure itself (e.g., benzodiazepine nucleus) [7].

- Methodology:

- Immobilization: Anchor the first building block (e.g., a 2-aminobenzophenone) to the solid support via the cleavable linker [7].

- Cyclization and Diversification: Perform sequential reactions on the solid support to form the scaffold core and introduce diversity at designated positions. For the benzodiazepine library, this involved cyclization and incorporation of amino acids and alkylating agents, creating 192 compounds with 4 points of diversity [7].

- Cleavage and Purification: Release the final compounds from the solid support under acidic conditions and purify them for screening [7].

- Outcome Analysis: The resulting library is screened against biological targets. The benzodiazepine library, for instance, identified high-affinity ligands for the cholecystokinin (CCK) receptor and the pro-apoptotic compound Bz-423, validating the scaffold's privileged status [7].

Protocol 2: Target Engagement and Mechanism of Action Studies

Following the identification of hits, this protocol aims to validate the target and elucidate the compound's mechanism of action.

- Objective: To confirm direct binding to the intended target and characterize the biochemical and phenotypic consequences.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Purified Target Protein: For structural and biophysical studies.

- Cellular Assays: Relevant cell lines for phenotypic screening (e.g., human leukemic cell lines for cytostatic effects) [7].

- Structural Biology Tools: Crystallography or Cryo-EM resources for structure determination.

- Methodology:

- Biophysical Binding Assays: Use techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to quantify binding affinity and kinetics between the hit compound and purified target protein.

- Cellular Phenotyping: Treat relevant cell lines with compounds and monitor outcomes. In the purine scaffold study, compounds like purvalanol A induced specific cell-cycle arrests (G2 or M-phase), which were characterized using flow cytometry [7].

- Structural Elucidation: Solve the high-resolution co-crystal structure of the target protein bound to the ligand. The structure of purvalanol B bound to CDK2's ATP-binding site provided a mechanistic understanding of its inhibitory activity and selectivity [7].

- Outcome Analysis: Determines the specificity and potency of the ligand. Structural data guides the rational design of next-generation compounds with improved properties [7].

Case Studies in Scaffold Application

The Pyridone Scaffold in Modern Drug Discovery

A 2025 review highlights pyridones as a contemporary privileged scaffold of significant interest [9]. These six-membered, nitrogen-containing heterocycles exist as 2-pyridones and 4-pyridones.

- Hallmarks Exhibited: Pyridones possess weak alkalinity and dual hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor propensities, which facilitate diverse interactions with biological targets [9]. They exhibit a wide range of bioactivities, including antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic properties, by regulating critical signaling pathways and downstream gene expression [9].

- Research Application: Their versatility makes them privileged fragments for designing molecules to address challenges like drug resistance. Current research focuses on optimizing their structure to enhance drug-like properties and advance them through clinical trials [9].

The Diaryl Ether (DE) Motif in Antiviral Therapy

The diaryl ether (DE) scaffold is a potent example of a privileged structure with demonstrated clinical success, particularly in antiviral drug development [6] [8].

- Hallmarks Exhibited: The DE motif confers high hydrophobicity and metabolic stability, improving cell membrane penetration and the overall drug-like profile of the molecule [6] [8].

- Research Application: The DE scaffold is a key component in FDA-approved HIV-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) like Etravirine and Doravirine [6] [8]. Structure-based drug design utilizing the DE core has led to inhibitors with picomolar to nanomolar potency against wild-type and mutant HIV strains. The scaffold's ability to engage in π-π stacking interactions with tyrosine residues (e.g., Y181, Y188) in the reverse transcriptase enzyme is a key mechanism of action [6].

Table 2: Privileged Scaffolds and Their Therapeutic Applications

| Scaffold | Therapeutic Area | Example Targets | Example Drugs/Leads |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine [7] [3] | CNS Disorders, Cancer | GABA-A Receptor, CCK Receptor | Diazepam, Bz-423 |

| Purine [7] | Oncology, Viral Infections | Cyclin Dependent Kinases (CDKs), EST | Purvalanol A, Purvalanol B |

| Diaryl Ether (DE) [6] [8] | Antiviral, Oncology | HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase, NS5B | Etravirine, Doravirine |

| Spiro Scaffolds [10] | Oncology, Pain, CNS | Topoisomerase II, VEGFR, PTHR1 | Cebranopadol, Ubrogepant |

| 2-Arylindole [7] | CNS Disorders | Serotonin Receptors | Not Specified (GPCR Ligands) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions as employed in the experimental protocols cited within this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Support (e.g., Geysen's Pin) [7] | Facilitates parallel synthesis and simplifies purification of library compounds during focused library synthesis. |

| 2-Aminobenzophenones [7] | Serve as key building blocks immobilized on solid support for the construction of benzodiazepine libraries. |

| Diverse Amino Acids [7] | Introduce chirality and structural diversity at a key position on the scaffold core during library synthesis. |

| Alkylating Agents [7] | Introduce aliphatic and aromatic diversity at a specific position on the scaffold core (N-alkylation). |

| Purified Target Proteins (e.g., CDK2) [7] | Enable biophysical binding assays and high-resolution structural studies (X-ray crystallography) for target engagement and MoA studies. |

| Relevant Cell Lines (e.g., Leukemic Cells) [7] | Used in phenotypic screening to assess the functional biological consequences of scaffold-based compounds (e.g., cell cycle arrest). |

Privileged scaffolds represent a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry, offering a strategic path to overcome the high costs and low hit rates often associated with drug discovery. Their defining hallmarks—versatile binding capacity and inherent drug-like properties—make them invaluable starting points for the development of chemical probes and therapeutic agents. As synthetic methodologies advance and our understanding of structure-target relationships deepens, the deliberate use of these scaffolds, informed by robust experimental workflows, will continue to be a critical driver of innovation in chemical biology and pharmaceutical research. Future efforts will likely focus on the identification of novel three-dimensional scaffolds, such as spirocyclic compounds, and their application against emerging and challenging therapeutic targets [10].

In the pursuit of new therapeutic agents, medicinal chemists have long recognized that certain molecular frameworks appear with surprising frequency across successful drugs targeting diverse biological pathways. These structures, termed "privileged scaffolds," provide versatile foundations for designing compounds with optimal drug-like properties and biological activity. The identification and understanding of such scaffolds accelerate drug discovery by providing validated starting points for new therapeutic programs. This review explores two quintessential examples of privileged scaffolds: the benzodiazepine core, foundational in central nervous system (CNS) therapeutics, and the diaryl ether motif, a highly versatile structure with demonstrated efficacy across antiviral, antibacterial, anticancer, and agrochemical domains. The benzodiazepine scaffold represents one of the most enduring CNS-active frameworks, while diaryl ether is statistically recognized as the second most popular and enduring scaffold within medicinal chemistry and agrochemical reports [11]. By examining the structural features, target interactions, and clinical applications of these scaffolds, this review provides a framework for understanding their privileged status and utility in chemical biology research.

The Benzodiazepine Scaffold in Clinical Medicine

Structural Features and Mechanism of Action

Benzodiazepines are a class of medications characterized by a fused benzene and diazepine ring structure, which exerts therapeutic effects by acting on benzodiazepine receptors in the central nervous system. These receptors are part of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptor, a ligand-gated chloride channel that serves as the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the mammalian brain [12]. The GABA-A receptor is a pentameric protein complex comprising five transmembrane subunits that collectively form a chloride channel. Benzodiazepines function as positive allosteric modulators, binding specifically to the interface between the α and γ subunits of the GABA-A receptor [13]. This binding induces a conformational change that increases the receptor's affinity for GABA, enhancing the frequency of chloride channel opening events in the presence of GABA. The resulting influx of chloride ions hyperpolarizes the neuronal membrane, reducing neuronal excitability and producing the characteristic sedative, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant effects [12].

Table 1: FDA-Approved Benzodiazepines and Their Primary Indications

| Drug Name | FDA-Approved Indications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Anxiety disorders, panic disorders with agoraphobia | High potency; rapid onset |

| Chlordiazepoxide | Alcohol withdrawal syndrome | First benzodiazepine synthesized |

| Clonazepam | Panic disorder, agoraphobia, myoclonic seizures, absence seizures | High potency; long-acting |

| Diazepam | Alcohol withdrawal management, febrile seizures (rectal form) | Rapid onset; active metabolites |

| Lorazepam | Anxiety disorders, convulsive status epilepticus | Reliable IM absorption |

| Midazolam | Convulsive status epilepticus, procedural sedation | Ultra-short acting; highly lipophilic |

| Clobazam | Seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome | 1,5-benzodiazepine; unique safety profile |

Pharmacokinetic Properties and Metabolism

The clinical utility of benzodiazepines is significantly influenced by their pharmacokinetic properties, particularly absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Most benzodiazepines are well-absorbed after oral administration, with the exception of clorazepate, which requires decarboxylation in gastric juices before absorption [12]. Distribution throughout the body is influenced by lipid solubility, with highly lipophilic agents like midazolam crossing the blood-brain barrier rapidly for quick onset of action. Benzodiazepines and their active metabolites exhibit high plasma protein binding, ranging from approximately 70% for alprazolam to 99% for diazepam [12]. Metabolism occurs primarily via hepatic pathways involving cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19. The metabolism typically proceeds through multiple phases: N-desalkylation (not applicable to triazolam, alprazolam, and midazolam), hydroxylation, and finally conjugation with glucuronic acid [12]. Lorazepam represents an exception, undergoing direct glucuronidation without cytochrome P450 metabolism, making it preferable for patients with hepatic impairment. Most benzodiazepines and their metabolites are excreted renally, with elimination half-lives that vary considerably among agents and are prolonged in elderly patients and those with renal dysfunction.

Experimental Protocols for Benzodiazepine Research

Receptor Binding Assays:

- Membrane Preparation: Isolate synaptic plasma membranes from rat or human brain cortex by homogenization in 0.32 M sucrose followed by differential centrifugation at 1000×g for 10 minutes and 100,000×g for 35 minutes.

- Radioligand Binding: Incubate membrane preparations (0.2-0.5 mg protein) with [³H]-diazepam (1-2 nM) and varying concentrations of test compounds in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 60 minutes.

- Separation and Quantification: Separate bound from free radioligand by rapid vacuum filtration through glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/B), followed by washing with ice-cold buffer. Measure radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting.

- Data Analysis: Determine IC₅₀ values from competition curves and calculate Ki values using the Cheng-Prusoff equation: Ki = IC₅₀/(1 + [L]/Kd), where [L] is radioligand concentration and Kd is its dissociation constant.

Electrophysiological Studies of GABA-A Receptor Function:

- Prepare Xenopus laevis oocytes injected with cRNA encoding human GABA-A receptor subunits (typically α₁, β₂, and γ₂S).

- Record chloride currents using two-electrode voltage clamp techniques at holding potentials of -60 to -80 mV.

- Apply GABA alone or in combination with benzodiazepines to determine potentiation of GABA-evoked currents.

- Calculate potentiation as % increase in peak current amplitude compared to GABA alone: [(IGABA+BZD/IGABA) - 1] × 100.

Diagram 1: Benzodiazepine mechanism of action at the GABA-A receptor (Title: Benzodiazepine Signaling Pathway)

The Diaryl Ether Motif: A Versatile Scaffold Across Therapeutics

Structural Characteristics and Privileged Status

The diaryl ether scaffold consists of two aromatic rings connected by an oxygen bridge, creating a structure with unique physicochemical properties that contribute to its privileged status in drug discovery. This scaffold demonstrates substantial hydrophobicity, favorable lipid solubility, excellent cell membrane penetration capability, and notable metabolic stability [14]. The oxygen bridge provides conformational flexibility while maintaining an optimal spatial orientation between the two aromatic systems, allowing for diverse interactions with biological targets. Statistically, the diaryl ether scaffold represents the second most popular and enduring framework in medicinal chemistry and agrochemical research, appearing in numerous natural products and synthetic bioactive compounds [11]. This widespread occurrence across successful therapeutic agents underscores its value as a versatile foundation for drug design.

Table 2: Clinically Approved Drugs Featuring the Diaryl Ether Scaffold

| Drug Name | Therapeutic Category | Primary Molecular Target | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib | Anticancer (BTK inhibitor) | Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase | Acrylamide warhead for covalent binding |

| Sorafenib | Anticancer (multikinase inhibitor) | VEGFR, PDGFR, RAF | Urea linker with pyridine ring |

| Nimesulide | NSAID (anti-inflammatory) | COX-2 | Methanesulfonanilide ring |

| Triclosan | Antimicrobial | Enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) | Chlorinated phenyl rings |

| Isoliensinine | Natural product (anti-cancer, antioxidant) | Multiple | Tetrahydroisoquinoline structure |

Target Diversity and Therapeutic Applications

The diaryl ether scaffold demonstrates remarkable versatility in its ability to interact with diverse biological targets across therapeutic areas. In oncology, drugs like ibrutinib and sorafenib incorporate the diaryl ether motif to achieve potent kinase inhibition through distinct mechanisms. Ibrutinib employs an acrylamide group that forms a covalent bond with cysteine residues in Bruton's tyrosine kinase, while sorafenib functions as a multi-kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR), and Raf kinase [11] [14]. In infectious disease therapeutics, the diaryl ether scaffold forms the foundation of direct inhibitors of InhA (enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase), a key enzyme in the mycobacterial fatty acid synthesis pathway essential for Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival [15] [16]. Notably, diaryl ether-based inhibitors like triclosan and its derivatives bypass the activation requirement of first-line tuberculosis drug isoniazid, offering potential solutions for drug-resistant tuberculosis strains. The scaffold's presence extends to central nervous system and cardiovascular therapeutics, with compounds under investigation for devastating neurological and cardiovascular conditions worldwide [14].

Synthetic Methodology: Chan-Lam Coupling for Diaryl Ether Formation

The construction of the diaryl ether motif can be achieved through several synthetic approaches, with the Chan-Lam coupling representing a particularly efficient and versatile methodology. This copper-catalyzed reaction enables the coupling of arylboronic acids with phenolic hydroxyl groups under mild conditions with high functional group tolerance.

Experimental Protocol for Chan-Lam Coupling [14]:

- Reaction Setup: In a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, combine 13α-estrone (1.0 equiv, 0.2 mmol) and arylboronic acid (1.2 equiv, 0.24 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (4 mL).

- Catalyst and Base Addition: Add copper(II) acetate (1.0 equiv, 0.2 mmol) and triethylamine (2.0 equiv, 0.4 mmol) to the reaction mixture.

- Reaction Conditions: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature under an air atmosphere for 16-24 hours, monitoring reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS.

- Workup Procedure: Upon completion, dilute the reaction mixture with dichloromethane (10 mL) and wash with saturated aqueous ammonium chloride solution (10 mL). Separate the organic layer and extract the aqueous layer with additional dichloromethane (2 × 10 mL).

- Purification: Combine the organic extracts, dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography on silica gel using hexane/ethyl acetate gradients to obtain the pure diaryl ether product.

Mechanistic Insight: The proposed mechanism involves three key stages: (I) coordination and transmetalation, where the copper catalyst interacts with both the boronic acid and phenolic oxygen; (II) disproportionation between CuY₂ and CuII(Ar)Y species; and (III) reductive elimination to form the C-O bond, yielding the diaryl ether product with terminal oxidation regenerating the active copper catalyst [14].

Diagram 2: Diaryl ether synthetic route (Title: Diaryl Ether Synthesis Workflow)

Case Studies in Targeted Drug Design

Overcoming Benzodiazepine Resistance in Epilepsy

Long-term administration of benzodiazepines for epilepsy management often leads to the development of tolerance and resistance, presenting significant clinical challenges. The mechanisms underlying benzodiazepine resistance involve complex adaptations at the molecular and network levels. Key resistance mechanisms include: (1) Downregulation of GABA-A receptors through enhanced endocytosis mediated by dephosphorylation of specific residues on the γ2 subunit (particularly Ser327), reducing receptor availability at the synaptic membrane [13]; (2) Alterations in receptor subunit composition, with decreased expression of the benzodiazepine-sensitive γ2 and α1 subunits and increased expression of less sensitive subunits such as α4 and α5 [13]; (3) Neuroinflammatory processes wherein cytokines like TNF-α promote GABAA receptor endocytosis and disrupt synaptic network balance [13]. Recent research has identified that in status epilepticus, GABA-A receptors containing synaptic γ2 subunits undergo selective internalization, resulting in diminished synaptic inhibition and development of benzodiazepine resistance during early stages of status epilepticus [13]. Understanding these mechanisms informs the development of next-generation benzodiazepines and adjunct therapies that circumvent resistance pathways.

Diaryl Ether Inhibitors for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis

The diaryl ether scaffold has emerged as a promising foundation for developing direct inhibitors of InhA to combat drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Unlike first-line drug isoniazid, which requires activation by bacterial catalase-peroxidase (KatG), diaryl ether-based inhibitors directly target the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (InhA) enzyme, circumventing a common resistance mechanism. Recent research has employed molecular hybridization strategies combining the diaryl ether scaffold with complementary bioactive fragments such as coumarins, triazoles, and pyrazoles to enhance potency against multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) strains [15] [16]. Structural studies reveal that optimized diaryl ether inhibitors access the minor portal of the InhA active site, forming critical interactions with the catalytic triad (Phe149, Tyr158, Lys165) and NAD+ cofactor [15]. These compounds demonstrate excellent inhibition of both InhA enzymatic activity (IC₅₀ values in low micromolar to nanomolar range) and mycobacterial growth, with maintained activity against katG-deficient strains. The structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies indicate that while lipophilicity contributes to membrane penetration and cellular activity, it is not the exclusive determinant of bioactivity, enabling optimization of drug-like properties while maintaining potency [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Scaffold-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function and Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Arylboronic Acids | Coupling partners for C-O bond formation in diaryl ether synthesis | Chan-Lam coupling reactions [14] |

| Copper(II) Acetate | Catalyst for C-O cross-coupling reactions | Diaryl ether synthesis via Chan-Lam reaction [14] |

| [³H]-Diazepam | Radioligand for GABA-A receptor binding studies | Benzodiazepine receptor affinity assays [12] |

| Native Cell Membrane Nanoparticles | Detergent-free system for membrane protein studies | Structural biology of benzodiazepine targets [17] |

| Recombinant GABA-A Receptor Subunits | Heterologous expression for receptor characterization | Electrophysiology studies of benzodiazepine mechanisms [13] |

| InhA Enzyme (M. tuberculosis) | Target protein for inhibitor screening | Evaluation of diaryl ether antitubercular activity [15] |

| Human Cancer Cell Lines (MCF-7, HeLa, A2780) | In vitro models for antiproliferative assessment | Testing diaryl ether-based anticancer agents [14] |

The benzodiazepine and diaryl ether scaffolds exemplify the concept of privileged structures in medicinal chemistry, demonstrating how specific molecular frameworks can yield diverse therapeutic agents with optimized properties. The enduring utility of these scaffolds stems from their ability to interact with multiple biological targets while maintaining favorable physicochemical characteristics. Benzodiazepines continue to serve as cornerstone therapies for neurological and psychiatric conditions despite challenges with resistance, while diaryl ethers offer expanding opportunities across infectious disease, oncology, and inflammation. Future directions in scaffold-based drug discovery will likely integrate artificial intelligence and generative models for structural optimization [18], alongside advanced structural biology approaches like the native cell membrane nanoparticle system that enables study of protein targets in near-physiological environments [17]. The continued investigation of these privileged scaffolds, informed by mechanistic understanding and innovative technologies, promises to yield next-generation therapeutics with enhanced efficacy and minimized resistance development.

Natural Products as an Evolutionary Source of Privileged Motifs

Natural products (NPs) represent Nature's exploration of biologically relevant chemical space through millions of years of evolution [19]. These secondary metabolites are synthesized by organisms via enzymatic cascades to carry out specific biological functions that provide a selective advantage in their environment [19]. Under the pressure of natural selection, nature has evolved to use a relatively limited set of simple building blocks to afford diverse and complex NP structures that interact with biologically relevant targets [20]. This evolutionary process has resulted in NPs occupying a strategic region of chemical space that is enriched with privileged structural motifs – molecular frameworks with inherent bioactivity and target affinity that make them particularly valuable for chemical biology research and drug discovery [21].

The biological relevance of NPs is fundamentally attributed to their co-evolution with proteins [20]. As NPs evolved to modulate biological systems, their structures were shaped to interact with diverse cellular targets, leveraging conserved protein folding types to achieve their functions [20]. This co-evolutionary process has endowed NPs with structural elements essential for protein interactions, making them prevalidated sources of inspiration for discovering new bioactive small molecules [19]. Through this evolutionary lens, NPs can be viewed as a library of privileged structures that have been optimized by nature to interact with biologically relevant targets, providing an invaluable resource for chemical biology and medicinal chemistry [19] [20].

Privileged Structural Motifs in Natural Products

Structural and Chemical Properties of Natural Products

Natural products possess distinctive structural characteristics that contribute to their biological relevance and differentiate them from synthetic compounds. NPs typically exhibit a high fraction of sp³ carbon atoms and abundant stereogenicity, features that contribute to their three-dimensional complexity and biological specificity [19]. These structural properties enable NPs to interact selectively with biological targets while maintaining favorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties [22]. The inherent balance between conformational rigidity and flexibility in many NP scaffolds allows them to maintain defined three-dimensional shapes while retaining sufficient adaptability to interact with multiple protein targets [22].

Statistical analyses of compound property distributions reveal significant differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry [21]. NPs tend to occupy a region of chemical space that is distinct from purely synthetic compounds, with properties that make them particularly suitable for modulating biological systems [21]. This unique positioning stems from the evolutionary pressure that has selected for NP structures capable of specific biological interactions while maintaining the physicochemical properties necessary for bioavailability within living systems [19] [20].

Classification and Examples of Privileged Motifs

Spirocyclic motifs represent an important class of privileged structures found in natural products that balance conformational rigidity and flexibility [22]. These distinct three-dimensional structures are free from the absorption and permeability issues characteristic of more flexible linear scaffolds, yet remain more conformationally adaptable than flat aromatic heterocycles [22]. Numerous spirocyclic systems with varying ring sizes and biological activities have been identified in NPs:

Table 1: Spirocyclic Motifs in Natural Products

| Spirocyclic System | Representative Examples | Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|

| [2.4.0] | Valtrate (9) [22] | Inhibits HIV-1 Rev protein mediated transport [22] |

| [2.5.0] | Illudins M and S (10, 11) [22] | Antitumor (Phase II clinical trials) [22] |

| [2.5.0] | (−)-Ovalicin (15), Fumagillin (16) [22] | Antiparasitic activities [22] |

| [2.5.0] | Duocarmycin SA (17), Duocarmycin A (18) [22] | Antitumor antibiotics [22] |

| [3.4.0] | Compound 19 [22] | Antibacterial activity [22] |

| [4.4.0] | Hyperolactones A (26) and C (27) [22] | Antiviral activity [22] |

| [4.4.0] | Mitragynine pseudoindoxyl (59) [22] | Opioid analgesic (mu agonism/delta antagonism) [22] |

BioCores, defined as privileged saturated and aromatic heterocyclic ring pairs, represent another significant category of privileged motifs identified through systematic analysis of known drugs and natural products [21]. These structural motifs serve as valuable starting points for the design of novel lead-like scaffolds in drug discovery programs [21]. The identification of BioCores leverages the evolutionary optimization embodied in natural product structures to guide the development of synthetically tractable compounds with enhanced probability of biological activity [21].

Beyond these classifications, numerous other privileged motifs exist in natural products, including fused ring systems, macrocyclic structures, and complex polycyclic frameworks. For example, limonoids (e.g., compounds 33-34) incorporate both [4.4.0] spirocyclic lactone and [2.4.0] spirocyclic oxirane motifs and have demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NO production in cellular models of inflammation [22]. The diversity of these privileged structural motifs in natural products provides a rich source of inspiration for the development of novel bioactive compounds.

Experimental Approaches for Natural Product Research

Extraction and Isolation Methodologies

The study of natural products begins with the extraction and isolation of bioactive compounds from their biological sources. Various extraction techniques are employed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Extraction Methods for Natural Products

| Method | Common Solvents | Temperature | Time Required | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration [23] [24] | Methanol, ethanol, or alcohol-water mixtures [24] | Room temperature [24] | 3-4 days [24] | Extraction of thermolabile components [23] |

| Percolation [23] [24] | Methanol, ethanol, or alcohol-water mixtures [24] | Room temperature [24] | Continuous process [23] | More efficient than maceration [23] |

| Soxhlet Extraction [24] | Methanol, ethanol, or alcohol-water mixtures [24] | Dependent on solvent boiling point [24] | 3-18 hours [24] | Standardized extraction of stable compounds [24] |

| Sonification [24] | Methanol, ethanol, or alcohol-water mixtures [24] | Can be heated [24] | 1 hour [24] | Rapid extraction with possible heating [24] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) [23] | Varies with target compounds | Elevated temperatures | Short duration | Enhanced efficiency for phenolic compounds [23] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) [23] | Typically CO₂ with modifiers | Controlled temperature and pressure | Moderate duration | Green extraction with minimal solvent [23] |

The selection of extraction solvent is crucial and depends on the chemical properties of the target compounds. Based on the principle of "like dissolves like," solvents with polarity values near that of the solute typically yield better extraction efficiency [23]. Alcohols such as ethanol and methanol are considered universal solvents for phytochemical investigations [23]. Other factors including particle size of the raw materials, solvent-to-solid ratio, extraction temperature, and duration significantly impact extraction efficiency and must be optimized for each specific application [23].

Following extraction, isolation of individual compounds typically employs chromatographic techniques. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) provides a simple, quick, and inexpensive method for initial analysis of mixture complexity and compound identity through Rf value comparison [24]. Bioautographic TLC methods combine chromatographic separation with in situ activity determination, facilitating localization and target-directed isolation of antimicrobial constituents [24]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) serves as a versatile, robust technique for the isolation of natural products, often serving as the method of choice for fingerprinting studies [24].

Structural Characterization and Bioactivity Screening

The structural elucidation of natural products relies heavily on advanced spectroscopic techniques, including Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and X-ray crystallography [25]. These methods enable researchers to determine the complete chemical structures of isolated compounds, including stereochemical configurations that are often critical for biological activity.

Bioactivity screening of natural products employs both target-based and phenotypic approaches. Cell-based phenotypic assays monitor effects on important cellular processes or signaling cascades, including glucose uptake, autophagy, Wnt and Hedgehog signaling, T-cell differentiation, and induction of reactive oxygen species [19]. Morphological profiling via the Cell Painting Assay provides a comprehensive method for evaluating compound-induced morphological changes across the entire cell [19]. This assay uses fluorescent microscopy and image analysis to generate characteristic morphological "fingerprints" that can reveal mechanisms of action and biological activities [19].

Bioautographic techniques are particularly valuable for identifying antimicrobial compounds from complex mixtures. These methods include: (1) direct bioautography, where microorganisms grow directly on the TLC plate; (2) contact bioautography, where antimicrobial compounds transfer from TLC plates to inoculated agar through direct contact; and (3) agar overlay bioautography, where seeded agar medium is applied directly onto the TLC plate [24]. The inhibition zones produced by these techniques help visualize the position of bioactive compounds in the TLC fingerprint, guiding subsequent isolation efforts [24].

Modern Approaches to Evolving Natural Product Structures

Pseudo-Natural Products: Chemical Evolution of NP Structure

The pseudo-natural product (pseudo-NP) concept represents an innovative approach to exploring biologically relevant chemical space beyond existing natural product structures [19] [20]. This strategy merges the biological relevance of NP structure with efficient exploration of chemical space through fragment-based compound development [19]. Pseudo-NPs are designed through de novo combination of natural product fragments in unprecedented arrangements that are not accessible through known biosynthetic pathways [19]. The resulting novel scaffolds retain the biological relevance of natural products but represent new chemotypes that may exhibit unexpected or unprecedented bioactivities [19].

The design principle of pseudo-NPs involves combining NP fragments to arrive at scaffolds that resemble NPs but are not obtainable through known biosynthetic pathways [19]. These fragments are typically derived from different biosynthetic origins and/or have different heteroatom content to ensure exploration of new chemical space [19]. NP-like fragments generally follow property criteria including AlogP < 3.5, molecular weight between 120 and 350 Da, ≤3 hydrogen bond donors, ≤6 hydrogen bond acceptors, and ≤6 rotatable bonds [19]. Fragment connection patterns include various fusion types (spiro, edge, bridged) and non-fused connections (monopodal, bipodal, tripodal) that generate structural diversity [19].

Cheminformatic analyses reveal that a significant portion of biologically active synthetic compounds can be classified as pseudo-natural products, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach for exploring biologically relevant chemical space [19]. The pseudo-NP concept can be viewed as the human-made equivalent of natural evolution – a chemical evolution of natural product structure that enables more rapid exploration of NP-like chemical space than natural evolutionary processes [19] [20].

Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) and Ring Distortion

Biology-oriented synthesis (BIOS) represents another NP-inspired strategy that focuses on core scaffolds of natural products [19] [20]. This approach employs hierarchical classification to identify simplified NP core structures that retain biologically relevant characteristics [19]. These scaffolds are then decorated with diverse appendages to generate compound collections that maintain relevance to NPs while achieving improved synthetic tractability [19]. While successful in discovering bioactive small molecules, BIOS is limited both biologically and chemically because the core scaffolds remain present in current NPs obtained through existing biosynthetic pathways [19].

The ring distortion strategy employs complex NPs as starting points for chemical transformations that dramatically alter their core structures [20]. This approach utilizes ring-based transformations including ring contraction, ring expansion, ring fusion, and ring cleavage to convert complex NPs into diverse and unprecedented structures [20]. The ring distortion strategy generates compounds that retain the complexity and biological relevance of NPs while exploring new regions of chemical space [20]. A limitation of this method is its requirement for sufficient amounts of multi-functionalized or complex NPs as starting materials to achieve diverse transformations [20].

Table 3: Comparison of Natural Product-Inspired Drug Discovery Strategies

| Strategy | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-Natural Products [19] [20] | De novo combination of NP fragments in unprecedented arrangements | Explores new biologically relevant chemical space; novel chemotypes | Requires careful fragment selection and connection design |

| Biology-Oriented Synthesis (BIOS) [19] [20] | Simplification of NP core scaffolds with diverse appendages | Synthetically tractable; retains biological relevance | Limited to known NP scaffolds; constrained chemical space |

| Ring Distortion [20] | Chemical transformation of NP cores through ring modifications | Generates complex, diverse structures from NP starting points | Requires complex NPs as starting materials |

| Function-Oriented Synthesis (FOS) [20] | Synthesis of simplified analogs retaining function of parent NP | Focused on specific biological function; improved synthetic access | Narrow chemical and biological space exploration |

| Total Synthesis [20] | Complete chemical synthesis of complex NPs | Enables study of mechanism and structure-activity relationships | Time-consuming; limited exploration of new chemical space |

Artificial Intelligence in Natural Product Research

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), is revolutionizing natural product drug discovery [25]. AI approaches enhance data analysis and predictive modeling, enabling more efficient exploration of NP chemical space [25]. Key applications of AI in NP research include:

- De novo drug design: AI algorithms, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning (RL), can design novel NP-inspired compounds with desired properties [25].

- Drug repurposing: AI can identify new therapeutic applications for known natural products by analyzing complex patterns in biological and chemical data [25].

- ADMET prediction: Machine learning models predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of NP-derived compounds, prioritizing candidates for further development [25].

- Molecular property prediction: AI models forecast bioactivity, selectivity, and other molecular properties based on chemical structure [25].

- Synthesis planning: AI systems propose synthetic routes for complex natural products and their analogs [25].

Natural language processing (NLP) algorithms can analyze extensive text data from scientific literature, patents, and NP-related databases, extracting crucial details about chemical structures, bioactivities, synthesis routes, and molecular interactions [25]. This information feeds into machine learning models for predictive analytics, virtual screening, and structure-activity relationship analysis, helping researchers better understand how molecular structures influence biological activity [25].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Natural Product Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards [24] | Catechin (1), Fucoxanthin (4), Sinomenine (5), Berberine (39) [23] | Chromatographic calibration, method validation, quantitative analysis |

| Chromatographic Materials [23] [24] | TLC plates, HPLC columns (various phases), Sephadex media [24] | Compound separation, purification, and analysis |

| Bioassay Reagents [19] [24] | Cell lines, assay kits, microbial strains | Biological activity screening, mechanism studies |

| Spectroscopic Resources [24] [25] | NMR solvents, reference compounds, crystallography reagents | Structural elucidation and characterization |

| Natural Product Databases [25] [21] | Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry database, NP-specific databases [21] | Cheminformatic analysis, dereplication, structural classification |

| AI/ML Tools [25] | InsilicoGPT, various machine learning platforms | Predictive modeling, data analysis, compound design |

Critical Methodological Frameworks

Dereplication strategies are essential in natural product research to avoid redundant rediscovery of known compounds [25]. These approaches combine analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, MS) with database searching to quickly identify previously characterized compounds in extracts [25]. Efficient dereplication saves significant resources by focusing isolation efforts on novel compounds with potential new bioactivities.

Bioassay-guided fractionation represents a cornerstone methodology in natural product discovery [24] [25]. This iterative process involves tracking biological activity through sequential extraction and purification steps to isolate the active constituents responsible for observed effects [24]. The approach ensures that isolation efforts remain focused on compounds with relevant biological activities rather than merely abundant or easily isolated substances.

Cheminformatic analysis of natural products enables quantitative assessment of chemical space coverage and NP-likeness [19] [20]. These computational approaches can calculate NP-likeness scores that evaluate structural similarity to known natural products, with more positive scores indicating greater similarity to NPs [20]. Such analyses help researchers design compound collections that maintain biological relevance while exploring new regions of chemical space.

Natural products represent an evolutionary optimized source of privileged structural motifs that have been shaped by millions of years of selection for biological relevance. The co-evolution of NPs with their protein targets has resulted in chemical structures pre-validated for bioactivity, making them invaluable starting points for drug discovery and chemical biology research. The distinctive structural features of NPs – including high sp³ character, stereochemical complexity, and balanced rigidity-flexibility – contribute to their success as privileged motifs for biological interactions.

Modern approaches to leveraging NP privileged structures continue to evolve, with pseudo-natural products, biology-oriented synthesis, and ring distortion strategies enabling more efficient exploration of NP-inspired chemical space. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods is further accelerating natural product research, from discovery and characterization to optimization and synthesis planning. As these technologies mature, they promise to enhance our ability to navigate the complex chemical space of natural products and their analogs, potentially leading to new therapeutic options for challenging diseases.

The future of natural product research will likely involve increasingly sophisticated integration of evolutionary principles with chemical design strategies. By understanding and applying the evolutionary logic underlying natural product biosynthesis and function, researchers can continue to develop novel privileged structures that expand the available toolbox for chemical biology and therapeutic development. The continued study of natural products as evolutionary optimized privileged motifs remains essential for addressing the complex challenges of modern drug discovery.

Distinguishing Privileged Structures from PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds)

In chemical biology and drug discovery, the observation that a particular compound or scaffold shows activity across multiple biological assays can be interpreted in two fundamentally different ways. On one hand, privileged structures are molecular scaffolds with inherent binding properties that allow them to provide potent and selective ligands for diverse biological targets through strategic functional group modifications [26]. These structures typically exhibit favorable drug-like properties and represent valuable starting points for lead optimization. Conversely, Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) represent molecular classes defined by common substructural motifs that frequently generate positive readouts in biochemical assays through various artifactual mechanisms rather than genuine target modulation [27]. This distinction is crucial for efficient drug discovery, as misclassification can lead to either the premature dismissal of valuable lead compounds or the wasteful pursuit of molecular mirages.

The concept of privileged structures has emerged as a fruitful approach to discovering new biologically active molecules. As described in a Special Issue on privileged structures in medicinal chemistry, "Privileged structures are molecular scaffolds with various binding properties. Single scaffolds, owing to the modification of functional groups, are usually able to provide potent and selective ligands for a range of different biological targets" [26]. These scaffolds often exhibit improved drug-like properties, making them particularly valuable for library design and lead generation strategies.

In contrast, PAINS constitute classes of compounds defined by common substructural motifs that encode for an increased probability of any member registering as a hit in any given assay, often independent of platform technology [27]. The biological activity associated with PAINS stems not from specific target engagement but from interference with assay systems through various mechanisms including chemical reactivity, metal chelation, redox activity, or physicochemical interference such as aggregation or fluorescence [27]. The challenge for researchers lies in accurately distinguishing between these categories to prioritize compounds with genuine therapeutic potential while avoiding costly investigations based on artifactual activity.

Defining Characteristics and Fundamental Differences

Privileged Structures: Strategic Molecular Platforms

Privileged structures represent chemical scaffolds that have evolved to interact meaningfully with multiple biological targets through specific molecular interactions. Their promiscuity stems from structural features that complement common binding elements in protein families, making them particularly valuable in drug discovery.

Core Properties: Privileged structures typically possess several key characteristics that differentiate them from PAINS. They demonstrate target-class specificity, meaning their promiscuity often extends across related targets within a protein family while maintaining selectivity against unrelated targets. This concept is exemplified by kinase inhibitors, where "owing to high sequence similarity in the active sites within a protein family, small molecule ligands often bind with high affinity to multiple members of that family" [28]. Additionally, privileged structures exhibit optimizable structure-activity relationships (SAR), where systematic modifications lead to predictable changes in potency and selectivity. They also display favorable drug-like properties, including appropriate molecular weight, lipophilicity, and metabolic stability profiles that make them suitable for further development.

Therapeutic Value: The practical utility of privileged structures is evidenced by their prominence in successful drug discovery campaigns. As noted by researchers, "the use of privileged structure scaffolds in medicinal chemistry embraces the James Black statement" that 'the most fruitful basis for the discovery of a new drug is to start with an old drug'" [26]. This approach acknowledges that molecular scaffolds with proven biological relevance provide productive starting points for new lead identification and optimization.

PAINS: Deceptive Molecular Artifacts

PAINS represent compounds that generate false positive results through interference with assay systems rather than genuine biological activity. Understanding their characteristics is essential for avoiding resource-intensive investigations based on artifactual signals.

Interference Mechanisms: PAINS compounds employ diverse mechanisms to generate false positive signals in assays [27]:

- Chemical reactivity: Compounds may react with biological nucleophiles (thiols, amines) or undergo photochemical reactions with protein functionalities

- Assay interference: Includes metal chelation that disrupts protein function or assay reagents, redox cycling, and physicochemical interference such as micelle formation or aggregation

- Signal interference: Compounds with intrinsic fluorescence, absorbance, or photochromic properties can directly interfere with detection methods

Structural Context: Importantly, PAINS identification is fundamentally class-based rather than compound-specific. As emphasized in the original PAINS research, "individual compounds recognized by a PAINS substructure do not necessarily exhibit broad spectrum interference" [27]. This distinction is crucial, as it highlights that PAINS designation relates to statistical probability of interference across multiple assay systems rather than guaranteed aberrant behavior in every context.

Table 1: Key Characteristics Differentiating Privileged Structures and PAINS

| Characteristic | Privileged Structures | PAINS |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Specific target engagement through defined molecular interactions | Assay interference through chemical reactivity or signal disruption |

| Structure-Activity Relationships | Reproducible and optimizable | Erratic or non-existent ("flat SAR") |

| Target Spectrum | Often limited to related target families | Broad, across unrelated targets and assay technologies |

| Drug-likeness | Typically good drug-like properties | Variable, often with reactive or unstable features |

| Behavior in Counterscreens | Activity persists in orthogonal assays | Activity disappears in appropriate counterscreens |

| Concentration Dependence | Appropriate potency at pharmacologically relevant concentrations | Often require high concentrations for effect |

Experimental Protocols for Distinction

Primary Triage: Computational and Early Experimental Assessment

The initial distinction between potential privileged structures and PAINS begins with computational analysis followed by targeted experimental triage.

Computational Filtering: Electronic PAINS filters can rapidly process thousands of compound structures to identify potential interference compounds [27]. However, this approach requires careful implementation with appropriate intellectual scrutiny rather than black-box application. As noted by researchers, "with such ease of use comes the danger that the appropriate degree of intellectual rigor and scrutiny of the screening context is not applied to this important process of compound triage" [27]. Additionally, computational assessment of privileged structures involves analysis of structural similarity to known privileged scaffolds and prediction of drug-like properties.

Hit Validation Protocols: Following computational triage, experimental validation is essential:

- Dose-response analysis: Determine potency and efficacy characteristics; PAINS often show incomplete curves or unusual Hill coefficients

- Compound purity assessment: Reproduce activity with repurified or resynthesized samples to exclude contaminants as activity source

- Detergent inclusion: Incorporate detergents like Tween-20 (0.01-0.05%) to disrupt aggregate-based inhibition [27]

- Orthogonal assay confirmation: Validate activity in different assay formats with distinct detection mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the primary decision pathway for distinguishing privileged structures from PAINS during initial triage:

Advanced Mechanistic Studies

For compounds passing initial triage, more sophisticated experiments can further elucidate their mechanism of action and distinguish true privileged scaffolds from subtle interference compounds.

Target Engagement Studies: Direct assessment of compound interaction with putative targets provides critical evidence for privileged structure designation:

- Cellular target engagement assays: Utilize techniques like cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) to confirm direct target binding in physiologically relevant environments

- Binding kinetics analysis: Determine association and dissociation rates using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or similar biophysical methods; PAINS often exhibit unusual binding kinetics

- Structural studies: Pursue X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to visualize compound binding modes

Polypharmacology Assessment: For confirmed privileged structures, detailed mapping of their target interactions informs therapeutic potential:

- Selectivity profiling: Screen against related target families to define selectivity windows

- Binding site analysis: Use computational tools like SiteHopper to identify potential off-targets through binding site similarity rather than sequence homology [28]

- Functional validation: Confirm functional effects on identified secondary targets

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Differentiating Privileged Structures from PAINS

| Experimental Method | Application | Interpretation for Privileged Structures | Interpretation for PAINS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose-response Analysis | Determine potency and efficacy | Clean sigmoidal curves with reasonable Hill coefficients | Abnormal curves, incomplete efficacy, or steep slopes |

| Orthogonal Assays | Confirm activity across different detection methods | Activity persists across multiple assay technologies | Activity limited to specific assay formats |

| Detergent Inclusion | Disrupt colloidal aggregates | Activity largely unaffected | Activity significantly reduced or abolished |

| Covalent Modification Assessment | Identify irreversible binding | Typically reversible binding | Often covalent modification of targets or assay components |

| Target Engagement Assays | Confirm direct target binding | Demonstrable target engagement in cellular contexts | Lack of specific target engagement despite functional activity |

| Counterscreens for Redox Activity | Identify redox cycling compounds | No significant redox activity | Frequently positive in redox assays |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Distinguishing Privileged Structures from PAINS

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PAINS Structural Filters | Computational identification of potential interference compounds | Initial compound triage and library design |

| AlphaScreen Technology | Robust assay platform used in original PAINS characterization [27] | Primary screening with detergent controls |

| Tween-20 Detergent | Disrupts compound aggregates that cause false positives [27] | Counterscreens for aggregation-based interference |

| SiteHopper Tool | Binding site comparison to identify potential off-targets [28] | Polypharmacology assessment for privileged structures |

| Orthogonal Assay Platforms | Different detection mechanisms (FRET, FP, SPR, etc.) | Confirmation of biological activity beyond primary screen |

| Covalent Modification Probes | Detect irreversible protein binding | Identification of chemically reactive compounds |

| Redox Activity Assays | Quantify redox cycling potential | Counterscreening for redox-based interference |

Structural and Chemical Properties: A Comparative Analysis

The molecular features that distinguish privileged structures from PAINS extend beyond simple structural alerts to encompass broader chemical properties and behaviors.

Privileged Structure Characteristics: True privileged scaffolds typically exhibit several favorable properties:

- Structural diversity potential: Ability to generate diverse analogs through synthetic modification

- Metabolic stability: Reasonable resistance to enzymatic degradation

- Balanced physicochemical properties: Appropriate lipophilicity, polar surface area, and molecular weight for cellular penetration

- Specific interaction motifs: Defined hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, or electrostatic interaction patterns

Natural products often provide inspiration for privileged structure development, as they represent "invaluable resources for drug discovery, characterized by their intricate scaffolds and diverse bioactivities" [18]. Their evolutionarily optimized interactions with biological systems make them particularly valuable starting points for privileged scaffold identification.

PAINS Substructure Alerts: While PAINS identification should not rely solely on structural filters, certain chemotypes have established associations with interference behavior:

- Problematic motifs: Originally identified classes include certain rhodanines, hydroxyphenylhydrazones, and enones [27]

- Emerging concerns: Continued research has identified additional problematic classes such as β-aminoketones, isothiazolones, and toxoflavins [27]

- Context dependence: Importantly, "a small proportion (ca. 5%) of FDA-approved drugs contain PAINS-recognized substructures" [27], highlighting that presence of a PAINS alert does not automatically preclude useful biological activity

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between chemical space, assay behavior, and appropriate classification of promiscuous compounds:

Accurately distinguishing privileged structures from PAINS requires integrated computational and experimental approaches with careful consideration of biological context. The essential differentiator lies in the nature of promiscuity: privileged structures engage in specific, reproducible interactions with biological targets, while PAINS produce activity through interference with assay systems. This distinction has profound implications for drug discovery efficiency and success.