Plackett-Burman Design: A Practical Guide to Efficient Screening for Pharmaceutical and Bioprocess Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Plackett-Burman (PB) experimental design, a powerful statistical screening tool for researchers and drug development professionals.

Plackett-Burman Design: A Practical Guide to Efficient Screening for Pharmaceutical and Bioprocess Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Plackett-Burman (PB) experimental design, a powerful statistical screening tool for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, demonstrating how PB designs efficiently identify critical factors from numerous candidates with minimal experimental runs. The content explores methodological applications across pharmaceutical formulation, bioprocess optimization, and analytical development, alongside advanced strategies for troubleshooting confounding effects and validating results. By integrating PB designs with optimization techniques like Response Surface Methodology, this guide supports the systematic, science-driven development of robust processes and products, aligning with Quality by Design (QbD) principles.

What is a Plackett-Burman Design? Unlocking Efficient Factor Screening

The Two-Level Screening Design

Core Concept and Definition

A Two-Level Screening Design is a type of experimental design used to efficiently identify the few key factors, from a large list of potential factors, that have a significant influence on a process or product output. When developing a new analytical method or optimizing a drug formulation, researchers often face numerous variables whose individual impacts are unknown. Screening designs allow for the investigation of a relatively high number of factors in a feasible number of experiments by testing each factor at only two levels (typically a high, +1, and a low, -1, setting) [1] [2].

The most common two-level screening designs are Fractional Factorial and Plackett-Burman designs [2]. The core principle is based on sparsity of effects; in a system with many factors, it is likely that only a few are major drivers of the response. Screening designs are a cost-effective and time-saving strategy for focusing subsequent, more detailed experimentation on these vital few factors [1] [3].

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Factor Levels | Two levels per factor (High/+1 and Low/-1). |

| Primary Goal | Identify which main effects are statistically significant. |

| Design Resolution | Typically Resolution III. |

| Confounding | Main effects are not confounded with each other but are confounded with two-factor interactions. |

| Assumption | Interaction effects between factors are negligible or non-existent at the screening stage. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

When should I use a Two-Level Screening Design?

You should use a screening design in the early stages of method optimization or robustness testing, when you have a large number of potential factors (e.g., more than 4 or 5) and need to identify the most important ones [3] [2]. It is ideal when your resources (number of experimental runs) are limited. A screening design helps you avoid the inefficiency of a full factorial design, which would require 2^k experiments (e.g., 7 factors would require 128 runs) [1].

What is the difference between a Plackett-Burman design and a Fractional Factorial design?

While both are Resolution III screening designs, they differ in the number of experimental runs available and the nature of confounding [3] [4].

| Feature | Plackett-Burman Design | Fractional Factorial Design |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Runs | A multiple of 4 (e.g., 12, 20, 24) [3] [5]. | A power of 2 (e.g., 8, 16, 32) [3] [4]. |

| Confounding | Main effects are partially confounded with many two-factor interactions [3]. | Main effects are completely confounded (aliased) with specific higher-order interactions [4]. |

| Flexibility | Offers more options for run size between powers of two [3]. | Limited to run sizes that are powers of two. |

Why can't I see interaction effects with a standard screening design?

Standard two-level screening designs are Resolution III designs. This means that while you can cleanly estimate all main effects, the main effects are "confounded" or "aliased" with two-factor interactions [1] [3]. In other words, the mathematical model cannot distinguish between the effect of a factor and its interaction with another factor. These designs operate on the assumption that interaction effects are weak or negligible compared to main effects, which is often a reasonable assumption for screening a large number of factors [3] [2].

What is a common mistake when analyzing data from a screening design?

A common mistake is using a standard significance level (alpha) of 0.05. In screening, the goal is to avoid missing an important factor (a Type II error). Therefore, it is a recommended strategy to use a higher alpha level, such as 0.10 or 0.20, when judging the significance of main effects. This makes the test more sensitive and reduces the chance of incorrectly eliminating an active factor. You can then use a more stringent alpha in follow-up experiments that focus on the important factors [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: My screening experiment did not identify any significant factors.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The range between the high and low levels for each factor was too narrow.

- Solution: The effect of a factor is the change in response from its low to high level. If this range is too small, the effect may be masked by experimental noise (error). For the next experiment, based on process knowledge, widen the factor level ranges to amplify the potential signal.

- Cause: The experimental error (noise) is too high.

- Solution: Investigate sources of variability in your measurement system or process execution. Implementing better process controls or using more precise measurement equipment can reduce background noise, making factor effects easier to detect.

- Cause: Important interactions are present and confounded with the main effects.

- Solution: If you have strong prior knowledge that certain interactions are likely, consider using a higher-resolution design (e.g., Resolution IV or V) from the start, even if it requires more runs. Alternatively, you can augment your original screening design with additional runs to de-alias the main effects from the interactions [3].

Issue 2: I have more than a dozen factors to screen.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The number of factors makes even a Plackett-Burman design too large.

- Solution: Consider a supersaturated design. These designs allow for investigating more factors than there are experimental runs. However, they require the strong assumption that only a very small number of the factors are active, and their analysis is more complex [5].

Experimental Protocol: Executing a Plackett-Burman Screening Design

The following workflow outlines the key steps for planning, executing, and analyzing a screening experiment.

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Define Objective and Select Factors: Clearly state the goal of the experiment. Select the factors to be investigated and define their practical high and low levels based on process knowledge or preliminary experiments [1] [3].

- Choose Design Size: Determine the number of experimental runs (N) based on the number of factors (k). A Plackett-Burman design can screen up to

k = N-1factors in N runs, where N is a multiple of 4 (e.g., 12 runs for 11 factors) [1] [5]. - Generate and Randomize: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab) to generate the design matrix. Randomize the run order to protect against systematic biases [1] [3] [4].

- Conduct Experiments and Analyze: Execute the experiments in the randomized order and record the response data for each run. Analyze the data by calculating the main effect for each factor and performing statistical significance testing (e.g., using a Pareto chart or normal probability plot of the effects) [1].

- Interpret and Follow-up: Identify the "vital few" significant factors. The logical next step is to design a further experiment, such as a full factorial or response surface design, to model the effects and interactions of these key factors in more detail and find their optimal settings [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following materials are commonly used in experiments designed to optimize analytical methods, such as the polymer hardness example from the search results [3].

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Resin & Monomer | Primary structural components of a polymer formulation; their ratio and type determine fundamental material properties. |

| Plasticizer | Additive used to increase the flexibility, workability, and durability of a polymer. |

| Filler | Additive used to modify physical properties, reduce cost, or improve processing (e.g., increasing hardness). |

| Chemical Solvents & Buffers | Used to create the mobile phase in HPLC method development; pH and composition critically affect separation. |

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized materials used to calibrate equipment and ensure the accuracy and precision of measured responses. |

Understanding Confounding in Resolution III Designs

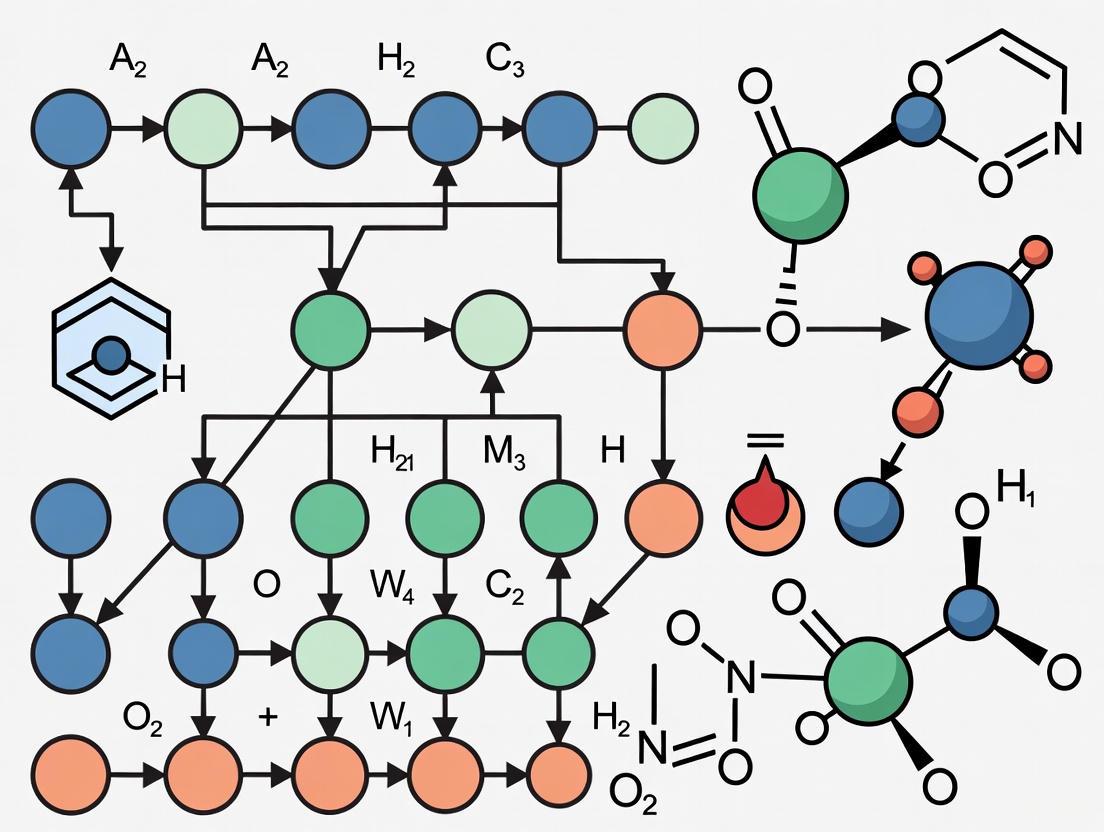

The diagram below illustrates the core concept of confounding in screening designs, where the estimated "Main Effect" is actually a mixture of the true main effect and one or more interaction effects.

Historical Context and Development by Plackett and Burman

The Plackett-Burman design is a highly efficient experimental methodology that has revolutionized the screening phase of research and development processes across numerous scientific disciplines. Developed in 1946 by statisticians Robin L. Plackett and J.P. Burman, this experimental design approach enables researchers to identify the most influential factors from a large set of variables with a minimal number of experimental runs [5]. For method optimization research in pharmaceutical development and other scientific fields, Plackett-Burman designs provide a strategic foundation for efficient resource allocation by focusing subsequent detailed investigations on the truly significant parameters. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for researchers implementing these designs in their optimization workflows.

Historical Background and Theoretical Foundations

Plackett and Burman published their seminal paper, "The Design of Optimal Multifactorial Experiments," in Biometrika in 1946 while working at the British Ministry of Supply [6] [5]. Their objective was to develop experimental designs that could estimate the dependence of measured quantities on independent variables (factors) while minimizing the variance of these estimates using a limited number of experimental trials [5].

The mathematical foundation of Plackett-Burman designs builds upon Hadamard matrices and earlier work by Raymond Paley in 1933 on orthogonal matrices [5]. These designs are characterized by their run economy, requiring a number of experimental runs that is a multiple of 4 (N = 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, etc.) rather than the power-of-2 structure of traditional factorial designs [6] [4]. This structural innovation provides researchers with more flexibility in designing screening experiments, particularly when investigating 11-47 factors where traditional designs would require prohibitively large numbers of runs [7].

Table: Key Historical Milestones in Plackett-Burman Design Development

| Year | Development | Key Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| 1933 | Discovery of Hadamard matrices construction method | Raymond Paley |

| 1946 | First publication of Plackett-Burman designs | Robin L. Plackett and J.P. Burman |

| 1993 | Extension to supersaturated designs | Dennis Lin |

| Present | Widespread application in pharmaceutical, chemical, and biotechnological research | Global scientific community |

Core Principles and Characteristics

Plackett-Burman designs belong to the family of Resolution III fractional factorial designs [3] [7]. The fundamental principle underlying these designs is the ability to screen a large number of factors (k) using a relatively small number of experimental runs (N), where N is a multiple of 4 and k can be up to N-1 [1] [8]. This efficiency makes them particularly valuable in early-stage experimentation where resources are limited and knowledge about the system is incomplete [9].

The key characteristics of Plackett-Burman designs include:

- Two-Level Factors: Each factor is tested at only two levels, typically coded as high (+1) and low (-1) settings [3] [1]

- Orthogonal Structure: The design matrix ensures that all main effects can be estimated independently without correlation [4]

- Confounding Structure: Main effects are partially confounded with two-factor interactions, requiring the assumption that interaction effects are negligible compared to main effects [3] [7]

- Saturated Main Effect Designs: All degrees of freedom are utilized to estimate main effects when k = N-1 [6]

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for implementing a Plackett-Burman design in method optimization research:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary purpose of a Plackett-Burman design in method optimization?

Plackett-Burman designs serve as screening tools to identify the "vital few" factors from a larger set of potential variables that significantly influence your response of interest [3] [9]. In method optimization research, this enables efficient resource allocation by focusing subsequent detailed optimization efforts only on the factors that demonstrate substantial effects, while eliminating insignificant factors from further consideration. This is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development where numerous process parameters must be evaluated with limited experimental resources.

How do I determine the appropriate number of runs for my experiment?

The number of runs (N) in a Plackett-Burman design must be a multiple of 4 (e.g., 8, 12, 16, 20, 24) [6] [4]. The specific number of runs depends on how many factors (k) you need to screen, with the constraint that k ≤ N-1 [7]. For example, if you have 7 factors to screen, you could use a 12-run design, while 15 factors would require at least a 16-run design. The table below provides common configurations:

Table: Plackett-Burman Design Configurations

| Number of Runs | Maximum Factors | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 11 | Early-stage screening with moderate factors |

| 16 | 15 | Larger factor sets with limited runs |

| 20 | 19 | Comprehensive screening with run economy |

| 24 | 23 | Extensive factor evaluation |

Can Plackett-Burman designs detect interaction effects between factors?

No, Plackett-Burman designs are Resolution III designs, meaning they cannot reliably estimate two-factor interactions [3] [7]. The main effects are confounded (partially aliased) with two-factor interactions [3] [4]. This confounding means that if you observe a significant effect, you cannot determine with certainty whether it comes from the main effect itself or from its interactions with other factors [3]. Therefore, these designs should only be used when you can reasonably assume that interaction effects are negligible compared to main effects [7] [8].

What are the limitations of Plackett-Burman designs?

The primary limitations of Plackett-Burman designs include:

- Inability to estimate interaction effects due to the Resolution III structure [3] [8]

- Limited to two levels per factor, preventing detection of curvature in response relationships [8]

- Potential for biased main effect estimates if significant interactions are present [3]

- Not suitable for definitive optimization, only for initial screening [8]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Confusing Results in Factor Significance

Issue: After conducting your Plackett-Burman experiment, the results indicate unexpected factor significance or the statistical analysis shows contradictory patterns.

Solution:

- Verify the randomization of your experimental runs was properly implemented to avoid systematic bias [1]

- Check for measurement error in your response data collection process

- Confirm that all factor levels were correctly set for each experimental run

- Consider adding center points to detect potential curvature in your response [9]

- Ensure that the assumption of negligible interactions is valid for your system [3]

Problem: How to Handle Potential Factor Interactions

Issue: You suspect that two-factor interactions may be significant in your system, potentially confounding your main effect estimates.

Solution:

- Use subject matter knowledge to identify potential significant interactions before designing your experiment

- If interactions are suspected, consider using a higher resolution design (Resolution IV or V) for critical factors [3]

- After identifying significant main effects, conduct follow-up experiments that specifically investigate potential interactions between the important factors [3] [8]

- Utilize a foldover design to de-alias specific interactions if needed [1]

Problem: Determining Optimal Factor Levels from Screening Results

Issue: You have identified significant factors but are unsure how to set their levels for subsequent optimization studies.

Solution:

- Examine the direction of each significant effect from the main effects plot [9]

- For continuous factors, set the level direction toward the improved response (higher or lower based on your objective)

- Use the magnitude of the effects to prioritize factors for subsequent response surface optimization [8]

- Consider practical constraints and operational boundaries when setting factor levels for follow-up experiments

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Plackett-Burman Design Implementation

The following workflow represents a generalized protocol for implementing Plackett-Burman designs in method optimization research:

Define Experimental Objectives: Clearly state the primary response variables to be optimized and identify all potential factors that could influence these responses [10]

Select Factors and Levels: Choose the factors to include in the screening design and establish appropriate high (+) and low (-) levels for each factor based on prior knowledge or preliminary experiments [3]

Create Design Matrix: Select the appropriate Plackett-Burman design configuration based on the number of factors. Statistical software such as JMP, Minitab, or other DOE packages can generate the design matrix [3] [7]

Randomize Run Order: Randomize the experimental run order to minimize the effects of uncontrolled variables and external influences [1]

Conduct Experiments: Execute the experimental trials according to the randomized run order, carefully controlling factor levels for each run

Measure Responses: Collect response data for each experimental run using validated measurement systems

Analyze Data: Calculate main effects and perform statistical significance testing using ANOVA or normal probability plots [1] [9]

Interpret Results: Identify significant factors based on both statistical significance and practical importance

Case Study: Bioelectricity Production Optimization

A 2023 study demonstrated the application of Plackett-Burman design for optimizing bioelectricity production from winery residues [10]. Researchers screened eight factors: concentration of the electrolyte, pH, temperature, stirring, addition of NaCl, yeast dose, and electrode:solution ratio. The 12-run Plackett-Burman design identified vinasse concentration, stirring, and NaCl addition as the most influential variables. These factors were subsequently optimized using a Box-Behnken design, achieving a peak bioelectricity production of 431.1 mV [10].

Case Study: Crude Oil Bioremediation Optimization

In a study on crude oil bioremediation, researchers employed Plackett-Burman design to identify critical factors affecting the biodegradation process by Streptomyces aurantiogriseus NORA7 [11]. The design identified crude oil concentration, yeast extract concentration, and inoculum size as significant factors. Subsequent optimization using Response Surface Methodology through Central Composite Design achieved 70% crude oil biodegradation under flask conditions and 92% removal in pot experiments [11].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Plackett-Burman Experimental Implementation

| Material Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | JMP, Minitab, R, Python DOE packages | Design generation, randomization, and data analysis |

| Laboratory Equipment | Precision measurement devices, environmental chambers, pH meters | Accurate setting of factor levels and response measurement |

| Experimental Materials | Chemical reagents, biological media, substrates | Implementation of factor level variations |

| Documentation Tools | Electronic laboratory notebooks, data management systems | Recording experimental parameters and results |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Methods

Plackett-Burman designs serve as effective screening precursors to more sophisticated optimization methodologies. Once significant factors are identified through Plackett-Burman screening, researchers typically proceed with response surface methodologies such as Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken designs for detailed optimization [11] [10] [8]. This sequential approach ensures efficient resource utilization while building comprehensive understanding of the factor-response relationships.

The following diagram illustrates this sequential experimental strategy:

Recent advances in Plackett-Burman applications include their use in constructing supersaturated designs for high-dimensional screening [5] and their integration with other design types for modeling complex systems with both categorical and numerical factors [5]. These developments continue to expand the utility of Plackett-Burman designs in contemporary research environments.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Plackett-Burman Experiments

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Significant factors are confounded with two-factor interactions.

- Cause: This is an inherent property of Resolution III designs, where main effects are aliased with two-factor interactions [3] [7].

- Solution: Verify the assumption that interactions are negligible through subject matter expertise. For follow-up experiments, consider augmenting your design with additional runs or using a definitive screening design to de-alias these effects [3].

Problem: The design requires studying curvature or quadratic effects.

- Cause: Plackett-Burman designs only test two levels per factor, making them incapable of detecting curvature [8].

- Solution: Once significant factors are identified through screening, optimize them using a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design such as Central Composite or Box-Behnken, which include three or more levels [12] [8].

Problem: Determining the correct number of experimental runs.

- Cause: The number of runs (N) must be a multiple of 4 (e.g., 12, 20, 24) and must be greater than the number of factors (k) you wish to study [3] [6].

- Solution: Use the guideline that you can screen up to N-1 factors in N runs. For example, a 12-run design can screen up to 11 factors, a 20-run design up to 19 factors, and so on [7] [6].

Problem: Experimental results are inconsistent or have high variability.

- Cause: Lack of randomization or replication in the experimental order.

- Solution: Always randomize the run order of your design to protect against systematic biases. If resources allow, include replication to obtain a better estimate of pure experimental error [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use a Plackett-Burman design instead of a standard fractional factorial?

- A: Plackett-Burman designs are ideal when you need more flexibility in run size. While standard fractional factorials come in run sizes that are powers of two (e.g., 16, 32), Plackett-Burman designs come in multiples of four (e.g., 20, 24, 28), offering options between these standard sizes. This is particularly useful when experimental constraints prevent you from using the larger standard design [3].

Q2: What does "partial confounding" mean, and how does it affect my analysis?

- A: In Plackett-Burman designs, each main effect is partially confounded with many two-factor interactions, unlike standard fractional factorials where effects are completely confounded with a single interaction. For example, in a 12-run design for 10 factors, a main effect like "Resin" may be partially confounded with 36 different two-factor interactions [3]. This spreads the potential bias across multiple estimates but increases the variance of each estimate. The analysis assumes these interaction effects are negligible.

Q3: Can I use a Plackett-Burman design to estimate interaction effects?

- A: Generally, no. These are Resolution III designs, which are not intended for estimating interactions. If you suspect significant two-factor interactions, a higher-resolution design (Resolution IV or V) should be used after the initial screening [3] [7].

Q4: What is a logical next step after completing a Plackett-Burman screening experiment?

- A: The standard approach is to take the few significant factors identified (typically 3-5) and study them in greater depth using a full factorial or optimization design (like RSM) to understand both their main effects and interactions, and to find optimal settings [3] [12].

Quantitative Data for Plackett-Burman Designs

Table 1: Standard Plackett-Burman Design Sizes and Properties

| Number of Runs | Maximum Number of Factors That Can Be Screened | Resolution | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 [3] [6] | 11 [6] | III [3] | Main effects are partially confounded with many two-factor interactions [3]. |

| 16 | 15 | III | Corresponding standard fractional factorial exists; often not a first choice for Plackett-Burman [7]. |

| 20 [3] [6] | 19 [7] [6] | III [3] | Provides an economical option between 16 and 32-run standard designs [3]. |

| 24 [3] [6] | 23 [6] | III [3] | Offers a balanced design for screening a very large number of factors [3]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Screening Design Methods

| Design Type | Run Sequence | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | 2^k (e.g., 8, 16, 32) [3] | Estimates all main effects and interactions [1]. | Number of runs becomes prohibitive with many factors [3] [1]. | Small number of factors (e.g., <5); requires full model understanding. |

| Fractional Factorial | Power of 2 (e.g., 8, 16, 32) [3] | Reduces runs while allowing estimation of some interactions at higher resolutions [3]. | Run sizes increase in large steps; less flexible for mid-sized experiments [3]. | Screening when some interaction information is needed. |

| Plackett-Burman | Multiple of 4 (e.g., 12, 20, 24) [3] | Highly economical; more flexible run sizes between powers of two [3] [1]. | Cannot estimate interactions (Resolution III); assumes interactions are negligible [3] [7]. | Initial screening of many factors to identify the vital few. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Plackett-Burman Design

The following workflow outlines the key stages for planning, executing, and analyzing a screening experiment using a Plackett-Burman design.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Objective and Factors: Clearly state the goal of the screening. List all potential factors (k) to be investigated and define their high (+1) and low (-1) levels precisely [3] [8].

- Select Design Size: Choose the number of runs (N), which must be a multiple of 4 and greater than k. For example, to screen 10 factors, a 12-run design is appropriate [3] [6].

- Generate Design Matrix: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab) or reference tables to generate the design matrix. This matrix specifies the factor level settings for each experimental run [1] [7].

- Randomize Run Order: Randomize the order in which the experimental runs are performed. This is a critical step to avoid systematic bias and validate statistical conclusions [1].

- Execute Experiment & Collect Data: Conduct the experiments in the randomized order and carefully record the response data for each run.

- Analyze Main Effects: For each factor, calculate the main effect as the difference between the average response at its high level and the average response at its low level [1].

- Identify Significant Factors: Use statistical tests (e.g., p-values at a significance level of α=0.10) and practical significance (effect magnitude) to identify the "vital few" factors that significantly impact the response [3].

- Plan Follow-up Experiments: Use the shortlist of significant factors to design more detailed experiments (e.g., full factorial or RSM) for optimization [3] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Microbial Growth Optimization (Example Application)

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Medium | Serves as the nutrient source for microbial growth. Can be a standard laboratory medium or an alternative substrate being evaluated. | Carob juice was used as a natural, nutrient-rich alternative culture medium for lactic acid bacteria [13]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintains a stable pH in the culture medium, which is often a critical factor for microbial growth and metabolism. | pH was identified as a statistically significant factor for the growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus [12]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., NaCl) | Used to control osmotic pressure and ionic strength in the medium, which can significantly influence cell growth. | NaCl concentration was screened and found to be a significant factor affecting cell growth [12]. |

| Precursor or Inducer Compounds | Specific chemicals required for the synthesis of the target metabolite or product. | The ratio of plant extract to silver nitrate (AgNO₃) was a significant factor in optimizing silver nanoparticle synthesis [14]. |

Understanding the Confounding Structure in Plackett-Burman Designs

The diagram below illustrates how effects are confounded in a Resolution III design, which is fundamental to proper interpretation of your results.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary purpose of a Plackett-Burman design? The Plackett-Burman (PB) design is a screening design used primarily in the early stages of experimentation to identify the few most important factors from a large list of potential factors that influence a process or product. It efficiently narrows down the field for further, more detailed investigation [1] [3] [15].

2. When should I choose a Plackett-Burman design over a standard fractional factorial? Consider a PB design when you need more flexibility in the number of experimental runs. Standard fractional factorials have run numbers that are powers of two (e.g., 16, 32). PB designs use multiples of four (e.g., 12, 20, 24), offering more options to fit budget and time constraints [3]. They are ideal when you are willing to assume that interaction effects between factors are negligible compared to main effects [1] [8].

3. Can I use a Plackett-Burman design to study interaction effects? No. PB designs are Resolution III designs, meaning that while you can independently estimate main effects, these main effects are aliased (confounded) with two-factor interactions [3] [7] [16]. If significant interactions are present, they can bias your estimates of the main effects. Therefore, PB designs should only be used when interactions are assumed to be weak or non-existent [1] [8].

4. What is a typical workflow after completing a Plackett-Burman screening experiment? The standard workflow is sequential:

- Screening: Use a PB design to identify the "vital few" significant factors from the "trivial many" [3] [17] [15].

- Optimization: Take the significant factors and conduct a further experiment, such as a full factorial, response surface methodology (RSM), or central composite design (CCD), to model interactions and find optimal factor settings [8] [18].

5. How many factors can I test with a given number of runs? A key feature of PB designs is their efficiency: you can study up to N-1 factors in N runs, where N is a multiple of 4 [1] [7] [6]. The table below outlines common design sizes.

| Number of Experimental Runs (N) | Maximum Number of Factors That Can Be Screened |

|---|---|

| 8 | 7 [17] |

| 12 | 11 [3] [15] [6] |

| 16 | 15 [8] |

| 20 | 19 [7] [6] |

| 24 | 23 [7] [6] |

Ideal Scenarios and Project Phases for Plackett-Burman Designs

Plackett-Burman designs are strategically employed in specific project phases and under certain constraints. The following workflow diagram illustrates the typical experimental progression where PB design is most applicable.

Ideal Use Cases

- Early-Stage Factor Screening: The primary use is at the beginning of a research or development project when many factors (e.g., 10, 15, or 20+) are being considered, and little is known about their individual impact [3] [17]. For example, in drug development, a PB design could screen numerous chemical components to find which ones significantly affect a drug's efficacy [17].

- Severely Limited Resources: When the cost, time, or material availability makes running a large number of experiments prohibitive. A PB design provides maximum information for a minimal number of runs. For instance, a 12-run PB design can screen 11 factors, while a full factorial would require 2,048 runs [15].

- Assumption of Effect Sparsity: These designs are most effective when the "sparsity of effects" principle holds—meaning only a few factors are expected to have large, significant effects on the response [16].

Critical Constraints and Limitations

- No Estimation of Interactions: PB designs cannot estimate two-factor interactions because these effects are confounded with (aliased to) the main effects [3] [16]. Interpreting results is risky if significant interactions are present.

- Two-Level Factors Only: The design only tests each factor at a high (+1) and low (-1) level. It cannot detect curvature in the response, meaning it assumes the relationship between a factor and the response is linear [8].

- One-Time Screening: PB designs are generally static. You cannot easily augment them with more runs to increase resolution without completely re-planning the experiment [8].

Example Experimental Protocol: Screening for Product Yield

1. Objective: Identify which of 11 potential process factors most significantly affect the yield of a new chemical product [15].

2. Experimental Design Summary:

- Design Type: Plackett-Burman

- Factors: 11

- Runs: 12

- Levels: Two per factor (High/Low)

3. Materials and Factor Setup: The table below details the factors and their levels for the experiment.

| Factor | Name | Low Level (-1) | High Level (+1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Fan speed | 240 rpm | 300 rpm [15] |

| B | Current | 10 A | 15 A [15] |

| C | Voltage | 110 V | 220 V [15] |

| D | Input material weight | 80 lb | 100 lb [15] |

| E | Mixture temperature | 35 °C | 50 °C [15] |

| F | Motor speed | 1200 rpm | 1450 rpm [15] |

| G | Vibration | 1 g | 1.5 g [15] |

| H | Humidity | 50% | 65% [15] |

| J | Ambient temperature | 15 °C | 20 °C [15] |

| K | Load | Low | High [15] |

| L | Catalyst | 3 lb | 5 lb [15] |

4. Procedure:

- Generate Design: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, DOE++) to create the 12-run PB design [3] [7] [15].

- Randomize Runs: Execute the 12 experimental trials in a random order to avoid systematic bias.

- Measure Response: For each run, record the product Yield.

- Analyze Data:

- Calculate the main effect for each factor (the difference in the average yield between its high and low levels).

- Use a half-normal probability plot or Pareto chart of the effects to visually identify factors that deviate from the "noise" [1] [15].

- Perform regression analysis or analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a higher significance level (e.g., α=0.10) to avoid missing potentially important factors [3].

5. Expected Outcome: The analysis will identify a subset of factors (e.g., 3-5) that have a statistically significant impact on yield. These factors then become the focus of a subsequent, more detailed optimization experiment [3] [15].

Core Terminology Explained

| Term | Definition | Role in Plackett-Burman Design |

|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | The average change in a response when a single factor is moved from its low to high level, averaged across all levels of other factors [1]. | The primary effects that Plackett-Burman designs are intended to estimate and screen for significance [3]. |

| Confounding | A phenomenon where the estimated effect of one factor is mixed up (aliased) with the effect of another factor or interaction [5]. | Main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions; they are not confounded with other main effects [1] [3]. |

| Design Matrix | A table of +1 and -1 values that defines the factor level settings for each experimental run [1]. | Provides the specific recipe for the experiment, ensuring orthogonality so that main effects can be estimated independently [19] [4]. |

| Resolution III | A classification for designs where main effects are not confounded with each other but are confounded with two-factor interactions [1] [3]. | Plackett-Burman designs are Resolution III, making them suitable for screening but not for modeling interactions [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What does it mean that main effects are confounded in a Plackett-Burman design?

In a Plackett-Burman design, the main effect you calculate for a factor is not a pure estimate. It is partially mixed with (or "aliased with") many two-factor interactions [3]. For example, in a 12-run design for 10 factors, the main effect of your first factor might be confounded with 36 different two-factor interactions [3]. This means that if a large two-factor interaction exists, it can distort the estimate of the main effect, potentially leading you to wrong conclusions. The design assumes these interactions are negligible to be effective for screening [20].

How do I know if a main effect is statistically significant?

After running your experiment, you will calculate the main effect for each factor [21]. To determine significance:

- Statistical Testing: Software will provide p-values (often denoted

Prob > |t|) for each effect. A common strategy in screening is to use a higher significance level (alpha) of 0.10 to avoid missing important factors [3]. - Normal Probability Plot: You can plot the calculated effects. Effects that are insignificant (close to zero) will fall along a straight line, while significant, active effects will deviate from this line [1] [9].

- Effect Magnitude: Rank the absolute values of the effects from largest to smallest. The largest effects are typically the most important, even before formal statistical testing [1].

The design matrix seems complex. How is it actually generated?

The design matrix is constructed to be an orthogonal array, often using a cyclical procedure to ensure balance and orthogonality [19] [4]. The process for many designs (like 12, 20, and 24-run) is:

- Start with a specific, predefined first row of +1 and -1 values.

- Generate the next row by taking the previous row and shifting all entries one position to the right, with the last entry wrapping around to the front.

- Repeat this cyclic shift until you have N-1 rows.

- Add a final row consisting entirely of -1 values [4]. This method creates a matrix where every factor is tested at a high level in exactly half the runs and a low level in the other half, and the settings of any two factors are uncorrelated [19].

My results seem counter-intuitive. Could confounding be the cause?

Yes, this is a common issue. If a large two-factor interaction is present, it can contaminate the estimate of a main effect. This can cause several problems:

- Missing an Important Factor: A factor with a small true main effect but involved in a large interaction might be mistakenly deemed insignificant.

- Incorrect Effect Sign: The direction of a factor's influence might appear reversed due to a strong, confounded interaction [20].

- False Positive: A factor with no real main effect might appear significant because of a large interaction.

If you suspect this, the next step is to run a follow-up experiment focusing only on the few significant factors identified. This follow-up experiment (e.g., a full factorial) can then properly estimate both the main effects and their interactions without confounding [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A factor believed to be important shows no significant effect. | Its main effect is small, but it might be involved in strong, confounded interactions that are masking its importance [20]. | Conduct a follow-up experiment focused on the top factors to estimate interactions. |

| The optimal factor settings from the design do not yield the expected result. | Confounding has led to an incorrect estimate of a main effect's sign or magnitude [20]. | Verify the optimal settings with a confirmation run. Use the design as a screening step, not a final optimization. |

| There is no way to estimate experimental error. | The design is "saturated," meaning all degrees of freedom are used to estimate main effects, leaving none for error [6]. | Replicate key runs or the entire design, include center points, or use dummy factors to obtain an estimate of error [3] [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential resources for planning and executing a Plackett-Burman screening experiment.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, R) | Used to generate the design matrix, randomize the run order, and perform the statistical analysis of the main effects [3] [22]. |

| Design Matrix Table | The core protocol for the experiment, specifying the exact high/low setting for every factor in every run [6]. |

| "Dummy" Factors | Factors that are included in the design matrix but do not represent a real experimental variable. Their calculated effects provide an estimate of the experimental error [22]. |

| Center Points | Experimental runs where all continuous factors are set midway between their high and low levels. A response shift at these points indicates the presence of curvature, suggesting a more complex model is needed [9]. |

Implementing Plackett-Burman Designs: A Step-by-Step Guide with Real-World Case Studies

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary objective of a Plackett-Burman design? The primary objective is to screen a large number of factors in a highly efficient manner to identify which few have significant main effects on your response, thereby guiding subsequent, more detailed experiments [3] [1]. It is used in the early stages of experimentation.

When should I choose a Plackett-Burman design over a standard fractional factorial? Choose a Plackett-Burman design when you need more flexibility in the number of experimental runs. Standard fractional factorials come in runs that are powers of two (e.g., 8, 16, 32), while Plackett-Burman designs come in multiples of four (e.g., 12, 20, 24), offering more options [3] [4].

How many factors can I test with a given number of runs? A Plackett-Burman design allows you to study up to N-1 factors in N runs, where N is a multiple of 4 [1] [23] [4].

What is a critical assumption of the Plackett-Burman design? A critical assumption is that interactions between factors are negligible compared to the main effects [3] [5]. The design is Resolution III, meaning main effects are not confounded with each other but are confounded with two-factor interactions [3] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Too many significant factors | Significance level (alpha) is too low. | In screening, use a higher alpha (e.g., 0.10) to avoid missing important factors [3]. |

| Unrealistic factor levels | Ranges are too wide or narrow based on process knowledge. | Re-define high/low levels based on prior experience or literature to ensure they are achievable and will provoke a response [23]. |

| Inability to estimate interactions | Using a Resolution III design. | This is inherent to the design. Plan a follow-up experiment (e.g., full factorial) with the vital few factors to study interactions [3]. |

| High cost or time per run | The initial number of runs is too high. | Use the Plackett-Burman design's property to minimize runs (e.g., 12 runs for 11 factors) compared to a full factorial [1] [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Defining Your Experiment

The following workflow outlines the key decision points and steps for defining a Plackett-Burman experiment.

Formulate a Clear Screening Objective

Begin by articulating a specific goal. A well-defined objective for a screening study typically aims to identify the critical factors affecting a key response variable.

- Example Objective: "To identify which of the 11 potential process parameters significantly affect the biomass yield of Lactobacillus acidophilus CM1." [23]

Select Factors and Define Levels

Brainstorm all potential factors that could influence your response, then define two levels for each.

- Action: Use process knowledge, literature, and brainstorming sessions (e.g., with SIPOC or cause-and-effect diagrams) to compile a list [24].

- Action: For each factor, set a high level (+1) and a low level (-1). These should be chosen to be sufficiently different to elicit a potential effect but remain within a realistic operating range [23].

- Example from Polymer Hardness Experiment: [3]

| Factor | Low Level (-1) | High Level (+1) |

|---|---|---|

| Resin | 60 | 75 |

| Monomer | 50 | 70 |

| Plasticizer | 10 | 20 |

| ... | ... | ... |

Determine the Appropriate Design Size

The number of experimental runs (N) must be a multiple of 4. You can screen up to N-1 factors in that number of runs [1] [4].

- Action: Choose the smallest value of N that accommodates your number of factors to maintain efficiency.

- Common Design Sizes: [3] [4]

| Number of Runs (N) | Maximum Number of Factors |

|---|---|

| 8 | 7 |

| 12 | 11 |

| 16 | 15 |

| 20 | 19 |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists common materials and their functions in experiments that utilize Plackett-Burman designs, drawn from cited research.

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) Medium | A standard, nutrient-rich culture medium used for the cultivation of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in bioprocess optimization [23]. |

| Vinasse Solution | A winery byproduct used as an electrolyte in bioelectricity production experiments; its organic content and ions facilitate redox reactions [10]. |

| NaCl (Sodium Chloride) | Added to solutions to increase ionic strength and conductivity, which can enhance processes like bioelectricity generation in microbial fuel cells [10]. |

| Yeast Extract | A common source of vitamins, minerals, and nitrogen in growth media, often optimized as a factor in microbial cultivation studies [23]. |

| Copper/Zinc Electrodes | A pair of electrodes with different electrochemical potentials, used to measure the potential difference (voltage) generated in an electrochemical cell [10]. |

| Arduino Microcontroller | Serves as a low-cost data acquisition system to measure and record potential difference between electrodes in real-time during experiments [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental rule for selecting the number of runs (N) in a Plackett-Burman design? The foundational rule is that a Plackett-Burman design allows you to screen up to k = N - 1 factors in N experimental runs, where N must be a multiple of 4 [3] [1] [4]. This makes these designs highly efficient for screening a large number of factors with a minimal number of experiments. Common sizes include N = 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28 [4] [25].

FAQ 2: I need to screen 10 factors. What are my options for N, and what are the trade-offs? You have two primary options, each with different implications for your experimental resources and statistical power.

- Option 1: N=12 Design. This is the most economical choice, as it allows you to study 11 factors in only 12 runs [3]. However, this design has very few degrees of freedom left to estimate error, which can result in low statistical power to detect significant effects unless the effect sizes are large [26].

- Option 2: N=16 Design. Choosing a larger design with 16 runs for your 10 factors provides a more robust analysis. The additional runs increase the degrees of freedom for error, which improves your power to detect smaller, yet still important, effects [4].

The table below summarizes the relationship between the number of factors and the available design sizes:

| Number of Factors to Screen (k) | Minimum Number of Runs (N) | Common Design Sizes (N) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 - 7 | 8 | 8, 12, 16, 20... [4] |

| 8 - 11 | 12 | 12, 16, 20, 24... [3] [4] |

| 12 - 15 | 16 | 16, 20, 24, 28... [4] |

| 16 - 19 | 20 | 20, 24, 28, 32... [1] [4] |

FAQ 3: What is a common pitfall when choosing a design size, and how can I avoid it? A common pitfall is selecting a design with too few runs (e.g., using an N=12 design for 11 factors), which results in an "underpowered" experiment [26]. An underpowered experiment has a high risk of concluding that a factor is not significant when it actually has an important effect on your response (a Type II error).

Troubleshooting Guide: Before conducting your experiment, perform a power analysis [26] [27]. This statistical calculation helps you determine the probability that your design will detect a effect of a specific size. For example, an engineer screening 10 factors found that an unreplicated 12-run design had only a 27% power to detect an effect of 5 units. By replicating the design three times for a total of 39 runs, the power increased to nearly 90% [26]. Use statistical software to run this analysis and ensure your chosen N provides adequate power.

FAQ 4: My experimental runs are expensive. Can I use an N=8 design for 7 factors? Yes, an N=8 design is a saturated Plackett-Burman design for 7 factors and is a valid, highly economical choice [4]. However, you must be aware of a major limitation: these small, saturated designs leave no degrees of freedom to estimate experimental error directly from the data. Consequently, you must rely on specialized data analysis techniques, such as normal probability plots or half-normal probability plots, to identify significant effects [1].

FAQ 5: How does the choice of N impact my ability to detect interactions between factors? All standard Plackett-Burman designs are Resolution III designs, regardless of the chosen N [3] [4]. This means that while you can clearly estimate main effects, each main effect is confounded (or aliased) with two-factor interactions [3] [20]. The validity of a Plackett-Burman design rests on the assumption that these interaction effects are negligible [3] [20]. If this assumption is violated, you may incorrectly attribute the effect of an interaction to a main effect. If you suspect significant interactions, a logical next step after screening is to run a follow-up optimization experiment with only the vital few factors, where you can use a larger design to estimate both main effects and interactions [3].

Workflow for Selecting the Design Size

The following diagram outlines the logical process for selecting the appropriate Plackett-Burman design size.

Research Reagent Solutions for a Plackett-Burman Experiment

The table below lists essential materials and their functions, based on a cited example of optimizing growth media for Lactobacillus acidophilus CM1 [23].

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| MRS Broth / Agar | A standard, complex growth medium used for the cultivation and maintenance of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) like Lactobacillus [23]. |

| Protease Peptone | Serves as a source of nitrogen and amino acids, which are essential building blocks for bacterial growth and biomass production [23]. |

| Yeast Extract | Provides a complex mixture of vitamins, cofactors, and other growth factors necessary for robust microbial proliferation [23]. |

| Dextrose (Glucose) | Acts as a readily available carbon and energy source for bacterial metabolism [23]. |

| Sodium Acetate & Ammonium Citrate | Buffer the medium and provide additional carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, helping to maintain stable growth conditions [23]. |

| Magnesium Sulfate & Manganese Sulfate | Essential trace minerals that act as cofactors for critical enzymatic reactions within the bacterial cell [23]. |

| Dipotassium Phosphate | A component of the buffer system that helps maintain the pH of the growth medium at an optimal level [23]. |

| Polysorbate 80 | A surfactant that can facilitate nutrient uptake by the bacterial cells [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the purpose of generating a Plackett-Burman design matrix? The design matrix is the experimental blueprint. It systematically defines the high (+) and low (-) level for each factor you are screening in every experimental run. Generating this matrix allows you to study up to N-1 factors in just N experimental runs, where N is a multiple of 4 (e.g., 8, 12, 16). This makes it a highly efficient screening tool for identifying the most influential factors from a large pool with a minimal number of experiments [3] [1] [5].

2. How do I determine the correct number of runs (N) for my experiment? The number of runs depends on how many factors you want to investigate. You need at least one more run than the number of factors. Standard sizes are multiples of 4 [3] [28]. The table below shows common configurations.

| Number of Factors to Screen | Minimum Number of Runs (N) |

|---|---|

| 3 - 7 | 8 |

| 8 - 11 | 12 |

| 12 - 15 | 16 |

| 16 - 19 | 20 |

3. What is the difference between a Plackett-Burman design and a full factorial design? A full factorial design tests all possible combinations of factor levels. While it provides complete information on main effects and interactions, the number of required runs grows exponentially with the number of factors (e.g., 7 factors require 2^7 = 128 runs). A Plackett-Burman design is a fractional factorial that sacrifices the ability to estimate interactions to drastically reduce the number of runs (e.g., 7 factors in only 8 runs), making it ideal for initial screening [1] [29].

4. Why is randomization a critical step, and how is it performed? Randomization is the random sequencing of the experimental runs given in the design matrix. It is essential to protect against the influence of lurking variables, such as ambient temperature fluctuations or instrument drift over time. By randomizing, you ensure these unknown factors do not systematically bias the effect of your controlled factors, leading to more reliable conclusions [1].

5. What are "dummy factors" and why should I include them? Dummy factors are columns in the design matrix that do not correspond to any real, physical variable. The effects calculated for these dummies are a measure of the experimental noise or error. If a real factor's effect is similar in magnitude to a dummy factor's effect, it is likely not significant. Including dummies helps in statistically validating which factors are truly important [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The design I generated does not have the expected number of runs.

- Potential Cause: Incorrect selection of the base design size.

- Solution: Verify that the number of runs (N) is a multiple of 4 and that it is greater than the number of factors you wish to study. For example, to screen 10 factors, you must use a design with at least 12 runs [3] [5].

Problem: After running the experiment and analyzing the data, a "dummy" factor appears to be significant.

- Potential Cause: The significant effect of a dummy variable indicates the presence of confounding. In Plackett-Burman designs, main effects are partially confounded with two-factor interactions. A significant dummy likely means that one or more two-factor interactions are active and are biasing the main effect estimates [3] [29].

- Solution: Assume interactions are negligible when using Plackett-Burman designs. If a dummy is significant, use subject matter expertise to identify potential interactions among your active factors. The next step should be a follow-up experiment (e.g., a full factorial or response surface design) focusing only on the few active factors to properly estimate these interactions [3] [1].

Problem: I am unsure how to analyze the data from my Plackett-Burman experiment.

- Solution: Follow a structured analysis protocol [28]:

- Calculate Main Effects: For each factor, calculate the difference between the average response at its high level and the average response at its low level.

- Estimate Experimental Error: Calculate the mean square (variance) of the effects from any dummy factors.

- Identify Significant Factors: Use an F-test (Factor mean square / Error mean square) or a normal probability plot to identify which factors have effects larger than what would be expected by chance alone.

Problem: My research field is biotechnology. Is there a proven example of this methodology?

- Solution: Yes. The methodology is widely applied. For instance, one study optimized phenol biodegradation by Serratia marcescens NSO9-1. Researchers used an 11-factor Plackett-Burman design in 12 runs to identify significant medium components like MgSO₄ and NaCl. This initial screening was later optimized using a Box-Behnken design, achieving a 41.66% phenol removal efficiency [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are essential for setting up and executing a screening experiment.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Experimental Factors | The variables (e.g., nutrients, pH, temperature) being tested at predetermined "high" and "low" levels to determine their effect on a response [30] [3]. |

| Dummy Factors | Placeholder variables included in the design matrix to estimate the experimental error and provide a baseline for judging the significance of real factors [28]. |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) Software | Tools like JMP or Minitab are used to automatically generate the randomized design matrix and analyze the resulting data, reducing manual calculation errors [3] [1]. |

| Random Number Generator | A tool (often built into DOE software) used to randomize the run order of the experiments to minimize the impact of uncontrolled, lurking variables [1]. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of steps for generating and utilizing a Plackett-Burman design matrix.

Screening Design Comparison

The table below compares Plackett-Burman with other common two-level factorial designs to help you select the right approach [3] [29].

| Design Type | Key Characteristics | Best Use Case | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plackett-Burman | Resolution III. Main effects are clear of other main effects but are confounded with two-factor interactions. Very economical. | Initial screening of a large number of factors (5+) where interactions are assumed to be negligible [1] [29]. | Cannot estimate interactions; results can be misleading if significant interactions exist. |

| Fractional Factorial (Resolution IV) | Main effects are clear of two-factor interactions, but two-factor interactions are confounded with each other. | Screening when you need to ensure main effects are not biased by interactions. More runs required than Plackett-Burman. | Requires more experimental runs than a Plackett-Burman design for a similar number of factors. |

| Full Factorial | Estimates all main effects and all interactions. Requires the largest number of runs. | When the number of factors is small (e.g., <5) and understanding interactions is critical. | The number of runs becomes prohibitively large as factors increase (2^k runs). |

Troubleshooting Guides for Hot-Melt Extrusion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common processing issues encountered during Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) and how can they be resolved?

Issues such as adhesive stringing, nozzle drip, and charring can disrupt production and compromise product quality. The table below outlines common problems, their causes, and solutions.

| Issue | Symptoms | Likely Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Stringing [31] [32] | Thin strands of adhesive ("angel hair") collecting on application equipment. | Low melt temperature (high viscosity); Nozzle too far from substrate; Incorrect temperature settings [31] [32]. | Increase melt temperature slightly; Adjust nozzle to be closer to the substrate; Verify uniform temperature across all zones (tank, hose, applicator) per adhesive manufacturer's instructions [31] [32]. |

| Nozzle Drip [31] [32] | Leakage or excessive flow from the applicator nozzle. | Worn nozzle or tip; Obstruction preventing full needle closure; Faulty module or inadequate air pressure [31] [32]. | Swab and clean the nozzle and seat; Replace worn parts; Check for and remove obstructions; Inspect module and air pressure [31]. |

| Charring/Gelling [31] [32] | Blackened, burnt adhesive; thick texture; smoke from the reservoir. | Temperature set too high; Oxidized adhesive; Debris accumulation in the nozzle [31] [32]. | Check thermostat and reduce temperature; Fully flush and scrub the tank to remove burnt debris; Clean the applicator nozzle daily [31] [32]. |

| Bubbles in Hot Melt [32] | Bubbles appearing on the applicator or the substrate. | Moisture in the tank or adhesive; Damaged valve allowing air into the system; Moisture in the substrate itself [32]. | Inspect tank and adhesive for moisture; Check and replace defective valves; Ensure substrate is dry before application [32]. |

Q2: My extrudate has inconsistent properties. Which process parameters are most critical to control?

Variability in the final product is often traced to inconsistencies in several key process parameters [33]. The table below summarizes these critical parameters and their impact on product quality.

| Process Parameter | Impact on Product Quality | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature [33] | Must be above the polymer's glass transition temperature (Tg) but below the degradation temperature (Tdeg) of both the polymer and the API. Influences melt viscosity, API stability, and can cause polymorphic changes [33]. | A stable, uniform temperature profile across the barrel is crucial. The temperature range between Tg and Tdeg offers the processing window [34]. |

| Screw Speed [33] | Affects residence time (how long material is in the barrel) and shear. Higher screw speed reduces residence time and increases shear, impacting mixing efficiency and potentially causing API degradation [33]. | Optimized alongside feed rate. It influences the Specific Mechanical Energy (SME) input, which is a key scale-up parameter [33]. |

| Screw Configuration [35] [33] | Determines the degree of mixing, compression, and shear. Configurable elements (kneading blocks, forward/conveying elements) are used to achieve specific mixing goals (dispersive vs. distributive) [35] [33]. | A twin-screw extruder offers much greater versatility for configuring screws compared to a single-screw extruder [35]. |

| Feed Rate [33] | The rate at which raw materials enter the extruder. Must be consistent and synchronized with screw speed. Inconsistent feeding causes fluctuations in torque and pressure, leading to non-uniform extrudates [33]. | Controlled using precision mass flow feeders to ensure a uniform delivery rate [35]. |

Q3: An electrical zone on my die is not heating properly. What is the systematic way to diagnose this?

A systematic approach is key to troubleshooting heater and electrical zone issues [36].

- Check Heater Resistance (Ohms): Using a multimeter, check the resistance (ohms, Ω) across the pins for the faulty zone. Compare the reading to the calculated value from the die's electrical drawing using Ohm's Law: Ohms = (Voltage × Voltage) ÷ Total Watts [36]. A significant deviation indicates a potential problem with the heater.

- Check Individual Heaters: If the zone resistance is incorrect, calculate and check the resistance of each individual heater. If a heater's reading differs from its calculated value and it has the correct voltage and wattage, it is likely faulty and needs replacement [36].

- Verify Electrical Connections and Thermocouples: With the die at ambient temperature, turn on power to one zone at a time. Confirm that the correct zone heats and that its thermocouple reports the temperature increase. If the wrong zone heats, there may be wiring or thermocouple placement errors [36].

- Inspect Control System: If a zone does not power on at all, check for a failed solid-state relay, a blown fuse in the control panel, or a loose/broken wire [36].

Integrating Plackett-Burman Design for Method Optimization

Screening Critical Factors with Plackett-Burman Design

In the context of a thesis focused on QbD, Plackett-Burman Design (PBD) is an extremely efficient statistical tool for the initial screening of a large number of potential factors to identify the "vital few" that significantly impact the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of an extrudate [1] [37]. This is crucial before proceeding to more resource-intensive optimization studies.

Key Characteristics of PBD:

- Economical: It allows screening of up to k = N-1 factors in only N experimental runs, where N is a multiple of 4 (e.g., 12 runs for 11 factors) [1].

- Resolution III Design: It efficiently estimates main effects but these effects are aliased (confounded) with two-factor interactions. This is acceptable for screening, where the goal is to identify large main effects [1].

- Two-Level Factors: Each factor is tested at a "high" (+1) and "low" (-1) level [38].

Experimental Protocol: Screening Excipients and Process Parameters

The following workflow details how to apply a PBD to an HME process, from defining the problem to analyzing the results.

Workflow for a Plackett-Burman Screening Experiment

1. Define Objective and Response

Clearly define the goal (e.g., "Identify factors most critical to achieving a target dissolution profile") and select a quantifiable response variable (e.g., % API released in 30 minutes) [33].

2. Select Factors and Levels Choose the excipients and process parameters to screen. For each, define a high (+1) and low (-1) level. The table below provides a hypothetical example.

| Factor | Type | Low Level (-1) | High Level (+1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: Polymer Grade | Material | Povidone 17 | Copovidone |

| B: Plasticizer Conc. | Formulation | 2% | 5% |

| C: Screw Speed | Process | 100 rpm | 200 rpm |

| D: Barrel Temp. (Zone 4) | Process | 140°C | 160°C |

| E: Antioxidant | Material | Absent | Present |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

3. Generate PBD Matrix and Execute Experiments Using statistical software (e.g., Minitab, JMP), generate an N-run PBD matrix. This creates a randomized list of experimental runs, each specifying the level for every factor [38] [1]. Conduct all HME experiments according to this design, measuring the response for each run.

4. Analyze Data and Identify Significant Factors Analyze the data to calculate the main effect of each factor. A large effect indicates a strong influence on the response. Use a combination of the following to identify significant factors [1]:

- Pareto Chart: Ranks the absolute values of the standardized effects.

- Normal Probability Plot: Significant effects will deviate from the straight line formed by negligible effects.

- Statistical Significance (p-values): Effects with a p-value less than a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.05) are considered statistically significant.

The significant factors identified through PBD then become the focus for subsequent, more detailed optimization studies using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to find their ideal settings [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate materials is fundamental to developing a successful and stable HME formulation. The table below lists key categories of excipients and their functions in pharmaceutical extrusion [35] [34].

| Category / Material Example | Key Function(s) | Critical Properties for HME |

|---|---|---|

| Polymers (Matrix Formers) | ||

| Copovidone (Kollidon VA 64) [34] | Primary matrix for solid dispersions; enhances solubility and provides sustained release. | Low Tg (~106°C); broad processing window; good solubilization capacity [34]. |

| PEG-VCap-VAc (Soluplus) [34] | Amphiphilic polymer ideal for solid solutions of poorly soluble drugs; acts as a solubilizer. | Very low Tg (~70°C) due to internal plasticization by PEG; very broad processing window [34]. |

| Plasticizers | ||

| Poloxamers (Lutrol F 68) [34] | Reduces polymer Tg and melt viscosity, easing processing and reducing torque. | Lowers Tg of the polymer blend; improves flexibility of the final extrudate [34]. |

| PEG 1500 [34] | Common plasticizer for various polymer systems. | Effective Tg reducer; compatible with many hydrophilic polymers [34]. |

| Other Additives | ||

| Surfactants (e.g., MGHS 40) [34] | Can further enhance dissolution and wettability of the API. | Thermally stable at processing temperatures. |

| Supercritical CO₂ [33] | Temporary plasticizer; produces porous, low-density foams upon depressurization. | Requires specialized equipment for injection into the melt. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common significant factors identified via Plackett-Burman design in probiotic media optimization? Across multiple studies, carbon sources (e.g., maltose, glucose, dextrose) and nitrogen sources (especially yeast extract) are consistently identified as the most significant factors positively affecting probiotic biomass yield [39] [40] [41]. For instance, in optimizing biomass for Lactobacillus plantarum 200655, maltose, yeast extract, and soytone were the critical factors [39]. Similarly, for Pediococcus acidilactici 72N, yeast extract was the only nitrogen source with a significant positive effect [41].

Q2: Why is the traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) method insufficient for full optimization? While OFAT is useful for preliminary screening of components like carbon and nitrogen sources, it has major limitations. It requires a large number of experiments when many factors are involved and, crucially, it disregards the interactions between factors [39]. Statistical methods like Plackett-Burman (PBD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) are more efficient and can account for these interactive effects, leading to a more robust optimization [39].

Q3: My biomass yield is lower than predicted by the model. What could be wrong? This discrepancy often stems from unoptimized physical culture conditions or scale-up effects. Even with an optimized medium composition, factors like pH, temperature, agitation speed, and initial inoculum size significantly impact the final yield [39] [40] [42]. For example, Bifidobacterium longum HSBL001 required specific initial pH and inoculum size [40], while the highest biomass for Lactobacillus plantarum 200655 was achieved in a bioreactor with controlled pH and agitation [39]. Ensure these parameters are also optimized and controlled.

Q4: How can I reduce the cost of the fermentation medium without sacrificing yield? A primary strategy is to replace expensive components with cost-effective industrial waste products or alternative food-grade ingredients. Research highlights the successful use of cheese whey, corn steep liquor, and carob juice as reliable and economical nitrogen or carbon sources [43] [44] [41]. One study for Pediococcus acidilactici 72N achieved a 67-86% reduction in production costs using a statistically optimized, food-grade modified medium [41].

Q5: After optimization, how do I validate that my probiotic's functional properties are intact? It is essential to functionally profile the probiotics cultivated in the new medium. This goes beyond just measuring biomass (g/L) or viable cell count (CFU/mL). Assessments should include tolerance to environmental stresses (low pH, bile salts), and where relevant, characterization of bioactive metabolite production using techniques like LC-MS metabolomic analysis [41].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High variation in response values during PBD screening.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent cultivation conditions (e.g., temperature fluctuations, inaccurate pH adjustment) or errors in medium preparation.

- Solution: Standardize protocols for media preparation, sterilization, and inoculation. Use calibrated instruments for pH and temperature control. Conduct all experiments with adequate replicates.

Problem: The optimized medium from RSM does not yield expected results in a bioreactor.

- Potential Cause: Scale-up effects. Parameters like mixing efficiency, oxygen transfer (even for anaerobes), and pH control differ between shake flasks and bioreactors.

- Solution: Re-optimize key fermentation parameters (e.g., agitation, aeration, pH control strategy) in the bioreactor. A fed-batch process with controlled nutrient feeding can often achieve higher cell densities [43] [40].

Quantitative Data from Optimization Studies

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent probiotic media optimization studies that employed Plackett-Burman and RSM.

Table 1: Summary of Optimized Media Compositions for Different Probiotic Strains

| Probiotic Strain | Optimal Carbon Source | Optimal Nitrogen Source(s) | Other Critical Components | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus plantarum 200655 | 31.29 g/L Maltose | 30.27 g/L Yeast Extract, 39.43 g/L Soytone | 5 g/L sodium acetate, 2 g/L K₂HPO₄, 1 g/L Tween 80, 0.1 g/L MgSO₄·7H₂O, 0.05 g/L MnSO₄·H₂O [39] | |

| Bifidobacterium longum HSBL001 | 27.36 g/L Glucose | 19.524 g/L Yeast Extract, 25.85 g/L Yeast Peptone | 0.599 g/L arginine, 0.8 g/L MgSO₄, 0.09 g/L MnSO₄, 1 g/L Tween-80, 0.24 g/L l-cysteine, 0.15 g/L methionine [40] | |

| Pediococcus acidilactici 72N | 10 g/L Dextrose | 45 g/L Yeast Extract | 5 g/L sodium acetate, 2 g/L ammonium citrate, 2 g/L K₂HPO₄, 1 g/L Tween 80, 0.1 g/L MgSO₄, 0.05 g/L MnSO₄ [41] | |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (Carob Juice Media) | Carob Juice | Carob Juice (inherent) | Components optimized via PBD/RSM; carob juice provides sugars and nutrients [44] |

Table 2: Biomass Yield Improvements Achieved Through Statistical Optimization

| Probiotic Strain | Biomass in Unoptimized/Base Medium | Biomass in Optimized Medium | Fold Increase & Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus plantarum 200655 | 2.429 g/L | 5.866 g/L (Bioreactor) | 1.58-fold higher in shake flask; high yield achieved in lab-scale bioreactor [39] | |

| Bifidobacterium longum HSBL001 | Not specified (Modified MRS as baseline) | 1.17 × 10¹⁰ CFU/mL (Bioreactor) | 1.786 times higher than modified MRS in a 3 L bioreactor [40] | |

| Pediococcus acidilactici 72N | Lower than optimized MRS | > 9.60 log CFU/mL (9.60 × 10⁹ CFU/mL) in Bioreactor | Significantly higher than commercial MRS; 67-86% cost reduction [41] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Initial Screening and Plackett-Burman Design Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps from preliminary screening to screening design.

- Basal Medium Preparation: Start with a basal medium. For lactic acid bacteria, this often includes salts (e.g., MgSO₄, MnSO₄), phosphate buffer (K₂HPO₄), a surfactant (Tween 80), and sodium acetate [39] [41].

- One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Screening:

- Carbon Sources: Supplement the basal medium with a single, fixed concentration of a carbon source (e.g., 20 g/L) and a standard nitrogen source. Test common sugars like glucose, maltose, sucrose, lactose, fructose, and galactose. Measure the response (biomass dry weight or OD600) after incubation [39] [40].

- Nitrogen Sources: Similarly, supplement the basal medium with a single, fixed concentration of a nitrogen source (e.g., 10 g/L) and a standard carbon source. Test sources like yeast extract, soytone, tryptone, peptone, and beef extract [39] [40].