PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies to Eliminate Non-Specific Amplification

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on identifying, troubleshooting, and preventing non-specific amplification in PCR.

PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies to Eliminate Non-Specific Amplification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on identifying, troubleshooting, and preventing non-specific amplification in PCR. Covering foundational concepts to advanced optimization strategies, it details common causes such as suboptimal annealing temperatures, poor primer design, and reagent issues. The guide offers practical, step-by-step solutions including protocol adjustments, specialized PCR methods, and validation techniques to ensure assay specificity and reproducibility in biomedical research and drug development.

Understanding Non-Specific Amplification: From Basics to Gel Recognition

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the goal is to amplify a specific, targeted DNA region. Non-specific amplification occurs when the reaction produces DNA fragments other than the intended target amplicon [1]. This unintended output can manifest as multiple bands on an electrophoresis gel, smeared lanes, or primer dimers. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing and troubleshooting these artifacts is critical, as they can compete with the desired product, reduce amplification efficiency, and compromise the validity of experimental results [2] [1]. This guide provides a systematic approach to identifying and resolving the common causes of non-specific amplification.

FAQ: Identifying Non-Specific Amplification

What does non-specific amplification look like on a gel?

When visualizing PCR products via gel electrophoresis, non-specific amplification presents several distinct patterns compared to a successful reaction, which typically shows one or more bright, discrete bands at the expected sizes [1].

The table below summarizes the common visual artifacts:

| Artifact Type | Description | Example Lane in Figure 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands | One or more unexpected bands of various sizes, either smaller or larger than the target amplicon [1] [3]. | Lanes 8, 9 |

| Smears | A continuous, fuzzy background or streak of DNA, indicating a vast range of randomly sized fragments [1]. | Lanes 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| Primer Dimers | A bright, compact band, often appearing as a fuzzy smear, at the very bottom of the gel (typically below 100 bp) [4]. | Lanes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| DNA Stuck in Well | PCR product fails to enter the gel, often due to malformed wells, overloaded product, or carryover of impurities [1]. | Lane 4 |

Figure 1: Model gel electrophoresis result showing a range of non-specific amplification and gel artefacts. Lanes 1 and 10 show correct, expected results for the assay. Lanes 2-9 demonstrate various types of non-specific amplification and artefacts, including residual primers, primer dimers, smears, and non-specific bands [1].

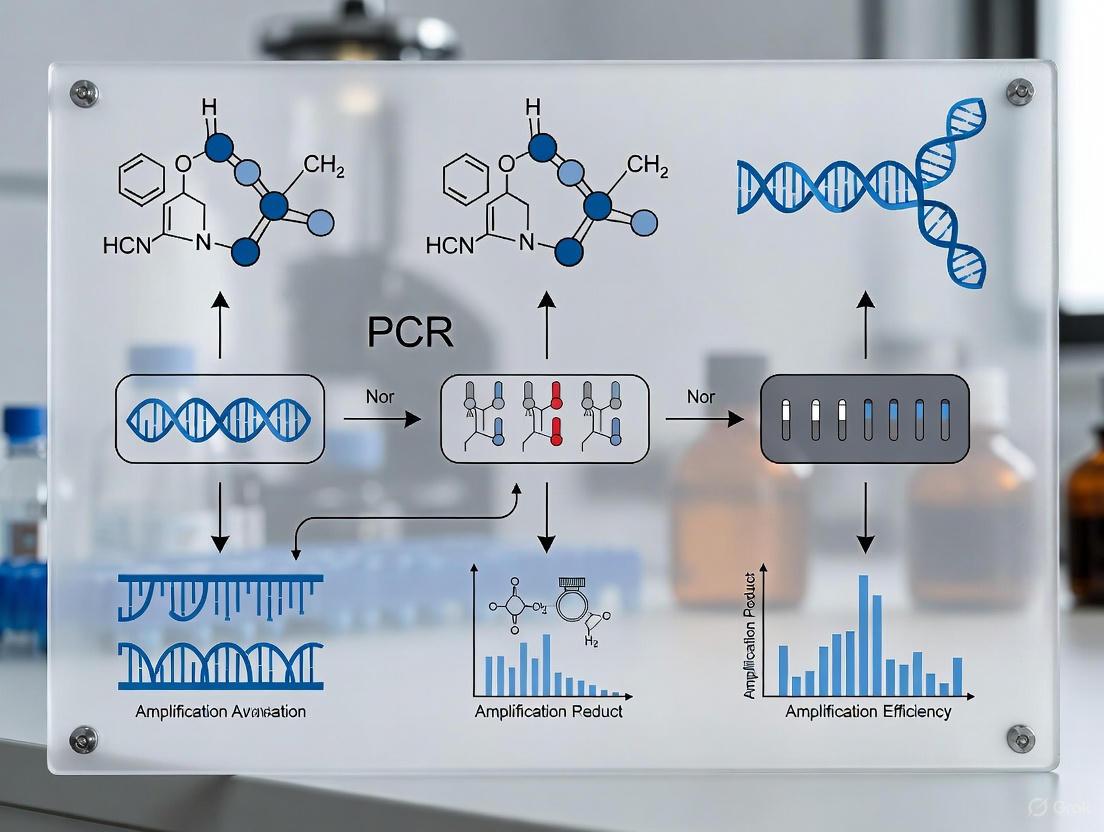

Figure 2: A systematic troubleshooting workflow for non-specific PCR amplification.

What is a primer dimer and how is it different from other artifacts?

A primer dimer is a small, unintended DNA fragment formed when two primers anneal to each other instead of to the template DNA [4]. They are typically 20-60 base pairs in length and appear as a bright, fuzzy band or smear at the very bottom of an electrophoresis gel [1]. Primer dimers form due to complementarity between primers, especially at their 3' ends, and are most likely to occur during reaction setup at low temperatures if a non-hot-start polymerase is used [5] [4]. While they are a form of non-specific amplification, they are common and not always a sign of a failed experiment, though they can compete for reagents and reduce the yield of the desired product [1] [4].

How can I confirm if smearing is due to contamination?

To determine if a smear is caused by contamination, always include a no-template control (NTC) in your PCR run. The NTC contains all reaction components except the DNA template [6].

- If the NTC is clean (no bands or smear), the smearing in your sample lanes is likely due to suboptimal PCR conditions, poor template quality, or problematic primer design [7].

- If the NTC shows the same smear, contamination is present in one of your reagents, consumables, or the workspace [7]. To isolate the source, systematically replace reagents (starting with water) with fresh aliquots until the contamination in the NTC disappears [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Causes and Solutions

The following table outlines the primary causes of non-specific amplification and provides targeted solutions to resolve them.

| Problem Category | Specific Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Primer-Related Issues | Poor primer design (e.g., complementarity at 3' ends) | Redesign primers; use online design tools; avoid GC-rich 3' ends and intra-primer homology [5] [3]. |

| Excessive primer concentration | Optimize primer concentration, typically within 0.1–1 µM; often 0.4–0.5 µM is ideal [5] [8]. | |

| Reaction Components | Annealing temperature too low | Increase annealing temperature in 1–2°C increments; optimal is often 3–5°C below the primer Tm [5] [7]. |

| Excess Mg2+ concentration | Optimize Mg2+ concentration; excess Mg2+ reduces fidelity and promotes mispriming [5] [3] [9]. | |

| Non-hot-start DNA polymerase | Use a hot-start polymerase to prevent spurious amplification during reaction setup [5] [3]. | |

| Template DNA & Cycling | Too much template DNA | Reduce the amount of template by 2–5 fold [7]. |

| Excessive number of cycles | Reduce the number of PCR cycles (e.g., to 25–35) to prevent accumulation of non-specific products [5] [8]. | |

| Complex template (GC-rich) | Use a polymerase designed for GC-rich templates; additives like DMSO or a GC enhancer can help [5] [7] [9]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and kits are specifically designed to help prevent or minimize non-specific amplification.

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Enzymes inactive at room temperature, preventing primer dimer formation and mispriming during reaction setup. Activated by high initial denaturation temperature [5] [8]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Enzymes with proofreading activity (e.g., Pfu, Q5, Vent) for applications requiring high accuracy, such as cloning. They typically have higher fidelity than standard Taq [2] [3]. |

| GC Enhancer / DMSO | PCR additives that help denature complex DNA secondary structures in GC-rich templates, improving specificity and yield [5] [9]. |

| dUTP and Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG/UNG) | A system to prevent carryover contamination. dUTP is incorporated into PCR products, and UDG degrades these products in future setups, leaving native DNA templates intact [6]. |

| Direct PCR Polymerases | Specialized enzymes (e.g., Terra PCR Direct Polymerase) tolerant to inhibitors in crude samples, reducing the need for pure DNA template and associated purification losses [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Annealing Temperature

A key method for increasing PCR specificity is to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature.

1. Principle: Using a gradient thermal cycler, a single PCR is run where the annealing temperature varies across the block. This allows you to test a range of temperatures simultaneously to find the one that produces the strongest target band with the least background.

2. Materials:

- Standard PCR reagents: template DNA, primers, dNTPs, MgCl₂, buffer, DNA polymerase.

- Gradient thermal cycler.

3. Procedure:

- A. Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components and dispense it equally into PCR tubes.

- B. Place the tubes in the thermal cycler, ensuring they span the desired temperature gradient.

- C. Set the annealing step of the PCR program to the "gradient" mode.

- D. Set the temperature range based on the primer Tm. A recommended starting gradient is from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm [5] [3].

- E. Run the PCR cycles.

- F. Analyze the products on an agarose gel.

4. Analysis: Identify the annealing temperature that yields the brightest target band with the absence or minimal presence of non-specific bands or smearing. This temperature should be used for future experiments with this primer pair.

Gel electrophoresis is the cornerstone technique for visualizing the products of a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). A properly run gel provides immediate, critical feedback on the success, specificity, and quality of your amplification. Within the broader context of PCR troubleshooting research, particularly concerning the pervasive challenge of non-specific amplification, adept gel interpretation is not merely a final step but an essential diagnostic tool. It allows researchers to distinguish a successful, specific reaction from one compromised by artefacts, informing subsequent optimization strategies. This guide provides a systematic, visual approach to diagnosing common electrophoretic artefacts, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to quickly identify issues and implement effective solutions.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Gel Electrophoresis Artefacts

The following section addresses the most frequently encountered problems when interpreting gel electrophoresis results. For each issue, potential causes and recommended solutions are detailed.

No Amplification or Faint Bands

- Visual Diagnosis: A lane shows no bands whatsoever, or bands are so faint they are barely detectable. The DNA ladder runs correctly, confirming the gel and stain are functional.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- PCR Failure: The amplification reaction itself failed.

- Solution: Verify that all PCR components were added to the reaction, including template, primers, dNTPs, and polymerase [10]. Always include a positive control to confirm reagent functionality.

- Solution: Increase the number of PCR cycles (e.g., by 3-5 cycles, up to 40 cycles) to amplify low-abundance templates [10].

- Insufficient Sample Loaded: The amount of DNA loaded into the well was too low for detection by your staining method.

- Solution: Concentrate dilute samples using ethanol precipitation or spin concentration prior to loading [11]. Increase the amount of PCR product loaded into the well.

- PCR Inhibition: The reaction was inhibited by contaminants co-purified with the template DNA.

- PCR Failure: The amplification reaction itself failed.

Non-Specific Amplification

- Visual Diagnosis: Multiple bands appear in a lane instead of a single, crisp target band. This is a primary focus of troubleshooting research and indicates that primers have bound to and amplified unintended regions [12].

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Suboptimal Annealing Temperature: The annealing temperature is too low, allowing primers to bind to sequences with partial complementarity [12] [10].

- Poor Primer Design or Quality: Primers may have hairpin structures or self-complementarity, leading to primer-dimer or off-target binding [12].

- Excessive Cycle Number: Too many PCR cycles can increase the amplification of non-specific products, especially in later cycles [12].

- Solution: Reduce the number of PCR cycles, typically to between 25-35 cycles [12].

- High MgCl₂ Concentration: Elevated Mg²⁺ concentrations can reduce reaction stringency and enhance non-specific binding [12] [10].

- Solution: Optimize the MgCl₂ concentration, typically within the 1.5-2.5 mM range [12].

Smearing

- Visual Diagnosis: A continuous "smear" of DNA is visible down the lane, rather than distinct bands. This indicates a population of DNA fragments of many different sizes.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Sample Degradation: The DNA template or the PCR product itself has been degraded by nucleases.

- Solution: Handle samples gently and keep them on ice. Use sterile, nuclease-free reagents and tubes [13].

- Excessive Voltage: Running the gel at too high a voltage causes overheating, which can denature DNA and melt the gel, leading to smearing [13] [14].

- Solution: Run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer duration [13].

- Contamination from Previous PCRs: Amplifiable DNA contaminants from earlier experiments can cause generalized smearing [15].

- Overloading the Well: Loading too much DNA can overwhelm the gel's sieving capacity.

- Solution: Load a smaller volume or dilute the sample before loading [14].

- Sample Degradation: The DNA template or the PCR product itself has been degraded by nucleases.

Distorted or Crooked Bands ("Smiling" or "Frowning")

- Visual Diagnosis: Bands curve upwards at the edges ("smiling") or downwards in the middle ("frowning"). This indicates uneven migration across the gel.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Uneven Heat Dissipation (Joule Heating): The center of the gel becomes hotter than the edges, causing samples in the middle to migrate faster [13].

- Solution: Reduce the running voltage to minimize heat generation. Use a power supply with a constant current mode to maintain a more uniform temperature [13].

- Improper Gel Tank Setup: An improperly seated gel, crooked electrodes, or uneven buffer levels create a non-uniform electric field [13].

- High Salt Concentration in Samples: Excess salt in a sample well creates a local region of high conductivity, distorting the electric field and migration [13].

- Solution: Desalt samples or dilute them to reduce salt concentration before loading [13].

- Uneven Heat Dissipation (Joule Heating): The center of the gel becomes hotter than the edges, causing samples in the middle to migrate faster [13].

Poor Band Resolution

- Visual Diagnosis: Bands are too close together, blurry, or poorly separated, making it difficult to distinguish molecules of similar sizes.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Suboptimal Gel Concentration: The pore size of the gel is not appropriate for the size range of your DNA fragments [13] [16].

- Solution: Use a higher percentage agarose gel to better resolve smaller fragments; use a lower percentage for larger fragments. See Table 1 for guidance.

- Gel Run for Incorrect Duration: Running the gel for too short a time does not allow for sufficient separation. Running it for too long can cause bands to diffuse [13].

- Solution: Run the gel for a longer duration at a lower voltage to improve separation [13].

- Overloading the Wells: Too much sample causes bands to become thick and merge.

- Solution: Load a smaller amount of sample per well [13].

- Suboptimal Gel Concentration: The pore size of the gel is not appropriate for the size range of your DNA fragments [13] [16].

Table 1: Selecting the Appropriate Agarose Gel Concentration

| Agarose Concentration (%) | Optimal Separation Range (bp) | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7% | 5,000 - 10,000+ | Genomic DNA, large PCR products |

| 1.0% | 1,000 - 10,000 | Standard PCR product verification |

| 1.5% | 200 - 3,000 | Standard PCR products, digests |

| 2.0% | 100 - 2,000 | Small PCR products, digests |

| 2.5% - 3.0% | 50 - 1,000 | Very small fragments, primer-dimer |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why are my DNA bands "smiling"? "Smiling" bands are typically caused by uneven heating across the gel, a phenomenon known as Joule heating. The center becomes hotter than the edges, causing DNA in the middle lanes to migrate faster, creating an upward curve. This can be resolved by lowering the voltage, using a power supply with a constant current mode, or ensuring the gel apparatus is properly assembled and level [13] [14].

How can I tell if the smearing in my gel is from degradation or contamination? Run a negative control (a reaction with no DNA template). If the negative control is blank, the smear is likely due to degradation of your sample or suboptimal PCR conditions (e.g., excessive cycles, low annealing temperature). If the negative control also shows a smear, this indicates contamination, most commonly from previous PCR products or contaminated reagents, and you must decontaminate your workspace and reagents [10].

What is the single most important factor for improving resolution in a gel? The gel concentration is the most critical factor. Selecting a gel with a pore size optimized for the size range of the DNA fragments you are separating is essential for achieving sharp, well-resolved bands [13]. Refer to Table 1 for guidance.

My gel run seems to have failed completely, with no bands visible, not even the ladder. What should be the first thing I check? If even the DNA ladder is not visible, the problem lies with the electrophoresis setup, not your PCR sample. First, confirm that the power supply was turned on and connected properly, and that the electrodes are functional. Second, check that you added DNA stain to the gel or staining solution and that the stain has not degraded [13] [14].

I see a bright, fast-migrating band at the bottom of my gel. What is it? This is very likely a primer-dimer, a short, artifactual product formed by the self-annealing of your PCR primers. It is promoted by high primer concentrations, low annealing temperatures, and primers with complementarity to each other. To prevent it, optimize primer concentration (typically 10 pM is ideal), increase the annealing temperature, and carefully design primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity [12] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Key Diagnostic Tests

Protocol: Testing for Protease Degradation in Protein Samples (SDS-PAGE)

While focused on protein electrophoresis, this protocol highlights a sample preparation artefact relevant to broader electrophoretic practice.

- Objective: To determine if multiple bands or smearing in a purified protein sample are due to protease activity during sample preparation [11].

- Materials: Protein sample, SDS-PAGE sample buffer, heating block, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system.

- Method:

- Divide your protein sample into two equal portions and add each to SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Tube A (Immediate Heat): Mix well and heat immediately at 95-100°C for 5 minutes.

- Tube B (Delayed Heat): Mix well and leave at room temperature for 2-4 hours. Then heat at 95-100°C for 5 minutes.

- Run both samples on an SDS-PAGE gel and stain.

- Interpretation: If the protein in Tube B shows significant degradation (more or lower molecular weight bands) compared to the intact protein in Tube A, proteases are active in your sample. For future preps, heat samples immediately after adding them to the denaturing sample buffer [11].

Protocol: Performing a Gradient PCR for Annealing Temperature Optimization

This is a fundamental experiment in PCR troubleshooting research to combat non-specific amplification.

- Objective: To empirically determine the ideal annealing temperature for a primer set to maximize specific product yield and minimize non-specific bands [12].

- Materials: Thermal cycler with gradient functionality, PCR reagents, primer set, template DNA.

- Method:

- Set up a master mix containing all PCR components (buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, template, primers).

- Aliquot the master mix into several identical PCR tubes.

- Place the tubes in the thermal cycler and program a gradient across the block (e.g., from 50°C to 65°C) for the annealing step of the PCR cycle.

- Run the PCR.

- Analyze all reactions on a high-resolution gel (e.g., 2-3% agarose).

- Interpretation: Identify the temperature that produces the strongest, single band of the expected size with the complete absence of non-specific bands or primer-dimer. This temperature should be used for all future standard amplifications with this primer set [12].

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for diagnosing common gel artefacts, integrating the information from the troubleshooting guide and FAQs.

Gel Artefact Diagnosis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Electrophoresis and PCR Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose | Polysaccharide gel matrix for separating DNA fragments (300 bp - 10,000+ bp) [16]. | Choose percentage based on target DNA size (see Table 1). Higher % for better resolution of small fragments. |

| Polyacrylamide | Gel matrix for high-resolution separation of very small DNA fragments (10-500 bp) or proteins [16]. | Used for sequencing or discriminating fragments differing by a single base pair. Requires more safety precautions. |

| DNA Stain (e.g., Ethidium Bromide, GelGreen/GelRed) | Intercalates into DNA double helix, allowing visualization under UV light [16]. | Safety and disposal protocols vary. Some modern stains are less mutagenic and more sensitive. |

| DNA Ladder/Marker | A mixture of DNA fragments of known sizes for estimating the size of unknown samples [14]. | Essential for every gel run. Choose a ladder with size ranges appropriate for your expected products. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified polymerase inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation before PCR begins [15] [10]. | Critical for improving specificity and yield. Activated only at high temperatures during the first denaturation step. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA strands. | Use balanced, high-quality dNTPs. Unbalanced concentrations can lead to misincorporation and errors [10]. |

| PCR Buffer with MgCl₂ | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerase activity. Mg²⁺ is a essential cofactor for the enzyme [12]. | Mg²⁺ concentration is a key optimization parameter (typically 1.5-2.5 mM). Too much can reduce specificity [12] [10]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | PCR additive that can bind to inhibitors often found in crude samples, preventing them from interfering with the polymerase [15]. | Useful when amplifying from complex samples like blood, soil, or plant extracts. |

Non-specific amplification occurs when PCR primers bind to unintended regions of the template DNA or to each other, leading to the synthesis of unwanted products instead of the desired target amplicon. This common issue compromises experimental results by reducing the yield of the specific product, generating false positives, and interfering with downstream applications like sequencing or cloning. The most prevalent causes can be categorized into three main areas: suboptimal annealing temperature, problematic primer design, and poor template quality. Understanding and troubleshooting these factors is essential for obtaining reliable PCR results.

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My gel shows multiple bands or bands of the wrong size. What is the most likely cause and how can I fix it?

Answer: The simultaneous presence of multiple bands or bands of unexpected size is most frequently caused by an annealing temperature that is too low or poorly designed primers that bind to non-target sites [5] [18].

- Primary Cause: Low annealing temperature reduces the stringency of primer binding, allowing primers to anneal to sequences that are partially complementary, leading to off-target amplification [5].

- Secondary Cause: Primers with complementarity to multiple genomic regions, or those with problematic sequences (e.g., long runs of a single base), can promote mispriming [19].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Calculate the melting temperature (Tm) of your primers. Start with an annealing temperature 3–5°C below the lowest Tm and perform a gradient PCR. Increase the temperature in 2–3°C increments to enhance specificity [5] [20].

- Check Primer Specificity: Use an in silico tool like NCBI's Primer-BLAST to verify that your primers are specific to your intended target and do not have significant homology to other sequences [21].

- Employ Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: Use a hot-start enzyme to prevent polymerase activity during reaction setup at low temperatures, which can minimize the synthesis of non-specific products [5] [18].

FAQ 2: I see a "smear" or a ladder-like pattern on my agarose gel. What does this indicate?

Answer: A smear or ladder-like pattern indicates widespread, random amplification, often resulting from poor template quality, excessive primer concentrations, or overly long PCR cycles [1] [15].

- Primary Cause (Smear): Degraded template DNA produces fragments of random sizes that can act as unintended templates or self-prime, resulting in a continuous smear of DNA. Excessive template input can also cause smearing [5] [1].

- Primary Cause (Ladder): Primer-dimer formation and subsequent amplification of primer multimers create a characteristic ladder pattern of bands at low molecular weights [1].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Assess Template DNA:

- Run the template DNA on a gel to check for integrity. A clean, high-molecular-weight band indicates good quality, whereas a smear indicates degradation [5].

- Re-purify the template to remove contaminants like salts, EDTA, or proteins that can inhibit the polymerase [5] [18]. For diluted or contaminated samples, use alcohol precipitation or a PCR cleanup kit [18].

- Optimize Primer Concentration: High primer concentrations promote primer-dimer formation. Titrate primer concentrations, typically between 0.1–1 μM, to find the level that minimizes artifacts while maintaining strong specific amplification [5] [18].

- Reduce Cycle Number: Avoid excessive cycles (generally do not exceed 35-40), as this leads to accumulation of by-products and nonspecific amplification, especially after the reaction reaches the plateau phase [5] [20].

FAQ 3: Even with a correct-sized band, my PCR product fails in downstream sequencing. Why?

Answer: This problem often stems from a mixture of specific and non-specific products that is not visible on the gel, or from low-fidelity amplification that introduces sequence errors [5] [22].

- Primary Cause: Non-specific products or primer-dimers co-migrate with the target band and are co-purified, leading to messy sequencing results [1].

- Secondary Cause: Polymerases with low fidelity or suboptimal reaction conditions (e.g., unbalanced dNTPs, excess Mg²⁺) can cause misincorporation of nucleotides, creating heterogeneous sequences [5].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Improve Reaction Specificity: Use the optimization strategies above (e.g., higher annealing temperature, hot-start polymerase) to produce a cleaner product. A nested PCR approach can also dramatically improve specificity [5].

- Use a High-Fidelity Polymerase: For cloning and sequencing, select a DNA polymerase with proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity to ensure high-fidelity amplification [5] [18].

- Ensure Balanced dNTPs and Mg²⁺: Use equimolar concentrations of all four dNTPs. Excess Mg²⁺ can increase misincorporation; optimize the Mg²⁺ concentration for your specific primer-template system [5].

The tables below consolidate key experimental parameters and their optimal ranges from troubleshooting guides.

Table 1: Optimization of PCR Reaction Components

| Component | Common Issue | Recommended Solution | Optimal Range / Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing Temperature | Too low, causing non-specific binding | Use gradient PCR to optimize | 3–5°C below primer Tm [5] [20] |

| Primer Concentration | Too high, causing primer-dimer | Titrate primer concentration | 0.1 – 1 μM [5] [18] |

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | Too high, reducing fidelity & specificity | Titrate Mg²⁺ concentration | Adjust in 0.2-1 mM increments [18] |

| Cycle Number | Too high, leading to plateau & artifacts | Reduce total number of cycles | 25–35 cycles (max 40) [5] [20] |

| Template Quality | Degraded or impure | Re-purify and assess via gel electrophoresis | High molecular weight, no smearing [5] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Non-Specific Amplification

| Observation | Primary Cause | Experimental Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands | Low annealing temperature; Mispriming | Increase annealing temperature in 2-3°C increments; Verify primer specificity with BLAST [5] [18]. |

| Primer-Dimers | High primer concentration; Primer complementarity | Lower primer concentration; Redesign primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity [5] [19]. |

| Smear on Gel | Degraded DNA; Long extension time; Excess template | Re-purify template DNA; Shorten extension time; Dilute template [5] [1]. |

| No Product | High annealing temperature; Poor template quality | Lower annealing temperature; Check template integrity and concentration [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Annealing Temperature Using Gradient PCR

This protocol is critical for establishing specific amplification conditions for a new primer set [20].

- Calculate Tm: Determine the Tm for both forward and reverse primers using the formula:

Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T)or a more sophisticated Nearest Neighbor method [20]. - Set Gradient: Program your thermal cycler with an annealing temperature gradient that spans a range, for example, from 5°C below the lowest Tm to 5°C above it.

- Run PCR: Perform the amplification reaction using the gradient.

- Analyze Results: Evaluate the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal temperature yields a single, strong band of the expected size with the absence of smearing or multiple bands.

- Refine: If necessary, run a second, finer gradient around the best temperature from the first round (e.g., in 1°C increments) for final optimization.

Protocol 2: Assessment and Purification of Template DNA

Ensuring template quality is a fundamental step often overlooked in troubleshooting [5] [18].

- Gel Electrophoresis:

- Mix 1 μL of template DNA with 6X loading dye and load onto a 0.8% - 1% agarose gel. Include a DNA molecular weight marker.

- Run the gel at 5-10 V/cm for 30-60 minutes and visualize under UV light.

- Interpretation: High-quality genomic DNA should appear as a single, tight high-molecular-weight band. A smear indicates degradation. Plasmid DNA can show supercoiled, nicked, and linear forms.

- Spectrophotometry:

- Measure the absorbance of the template DNA at 260 nm and 280 nm.

- Interpretation: An A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8 indicates pure DNA. Significant deviation may suggest protein (lower ratio) or RNA/contaminant (higher ratio) contamination.

- Re-purification (if needed):

- If quality is poor, re-purify the template via phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation, or use a commercial DNA clean-up kit [18].

- Re-assess the purified DNA using the steps above before proceeding with PCR.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for troubleshooting non-specific amplification, mapping symptoms to primary causes and corresponding solutions.

PCR Troubleshooting Decision Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Preventing Non-Specific Amplification

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Troubleshooting | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents enzymatic activity during reaction setup, drastically reducing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation [5] [15]. | Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase, OneTaq Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [5] [18]. |

| PCR Additives / Co-solvents | Helps denature complex DNA (e.g., GC-rich templates) and stabilizes the reaction, improving specificity and yield [5]. | DMSO, Betaine, GC Enhancer [5]. |

| Mg²⁺ Solution | Cofactor for DNA polymerase; its concentration is critical and must be optimized to balance yield and fidelity [5] [18]. | MgCl₂, MgSO₄ (for certain polymerases like Pfu) [5]. |

| dNTP Mix | Balanced equimolar concentrations of all four dNTPs are essential to prevent misincorporation and ensure high-fidelity amplification [5]. | Prepared mixes from various suppliers. |

| Primer Design Software | In silico tools are indispensable for designing specific primers and checking for self-complementarity or off-target binding [19] [21]. | NCBI Primer-BLAST [21]. |

Non-specific amplification in Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) occurs when primers bind to unintended regions of the DNA template, leading to the synthesis of non-target DNA fragments alongside the desired amplicon [1] [15]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these artifacts are not merely minor inconveniences; they represent a critical failure point that can severely compromise the integrity and reliability of downstream applications.

The presence of primer-dimers, smeared bands, or multiple unexpected bands on an electrophoresis gel indicates a problem that extends beyond the PCR tube [1]. When these non-specific products are carried into subsequent workflows like sequencing or cloning, they can cause failed reactions, ambiguous data, inaccurate results, and ultimately, a significant waste of time and resources. This guide provides a systematic, troubleshooting-focused approach to identifying, resolving, and preventing the effects of non-specific amplification to ensure the success of your critical experimental pipelines.

FAQs: Understanding the Downstream Consequences

Q1: How does non-specific amplification specifically interfere with Sanger sequencing?

Non-specific amplification compromises Sanger sequencing in several key ways [1] [23]. The sequencing reaction itself can initiate from multiple, unintended DNA templates (primer-dimers, non-target amplicons), in addition to your target. This produces overlapping chromatograms with multiple peaks starting at the same position, making the sequence data unreadable and impossible to interpret accurately. Furthermore, the presence of these extra products can reduce the available reagents for the target amplicon, leading to a weak or failed sequencing reaction. Even if a sequence is obtained, it may be from a non-target fragment, providing completely erroneous genetic information.

Q2: Why are non-specific products problematic for cloning experiments?

In cloning, non-specific products pose a major threat to efficiency and accuracy [24]. Ligation and transformation steps will proceed with whatever DNA fragment is present. If your PCR product is a mixture of target and non-target DNA, you will generate a population of colonies containing a variety of inserts. This necessitates labor-intensive screening of an excessively large number of colonies to identify the one with the correct insert, a process that is both time-consuming and expensive. There is also a high risk of selecting and propagating a clone with an incorrect insert, which can lead to invalid experimental conclusions downstream.

Q3: What is the impact on quantitative diagnostic reliability, such as in qPCR?

For quantitative diagnostics, non-specific amplification directly undermines the assay's fundamental purpose: accurate quantification [15]. The fluorescent dyes or probes used in qPCR will intercalate or bind to all double-stranded DNA products, not just the target. This means the reported fluorescence—and the subsequent calculation of template concentration—will be artificially inflated, leading to a potentially severe overestimation of the target's abundance. This can result in false positives or an incorrect assessment of pathogen load or gene expression level, with serious implications for diagnostic conclusions.

Q4: Can purification methods always remove non-specific amplification products?

Not always. While standard enzymatic clean-up or size-selection methods can effectively remove common contaminants like single-stranded primers and primer-dimers, they are less effective for more complex non-specific artifacts [1]. Primer multimers, which can form ladder-like patterns, and smears composed of a vast range of fragment sizes are particularly difficult to remove completely. Furthermore, if the non-specific product is very close in size to your target amplicon, physical separation methods like gel extraction or bead-based size selection will fail to resolve them, resulting in a co-purified mixture.

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Approach

When non-specific amplification is suspected, a systematic approach to troubleshooting is essential. The following table outlines common symptoms, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Systematic Troubleshooting for Non-Specific Amplification

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands or Unexpected Band Sizes [5] [24] | • Annealing temperature too low• Primer concentration too high• Mispriming due to poor primer design• Excess Mg2+ | • Increase annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments [5] [24].• Optimize primer concentration (typically 0.1-1 µM) [5].• Check primer specificity using tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST [25].• Decrease Mg2+ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [24]. |

| Smear of DNA on agarose gel [1] [15] | • Degraded DNA template• Contaminated primers• Too many PCR cycles• Excess template DNA | • Re-purify or re-synthesize DNA template/primers [1].• Reduce the number of cycles (e.g., 25-35 is standard) [5].• Dilute DNA template 10-100x to reduce self-priming [1]. |

| Primer-Dimer (band at bottom of gel) [1] [15] | • 3'-end complementarity between primers• High primer concentration• Enzyme activity during setup | • Redesign primers to avoid 3' complementarity [25].• Lower primer concentration [5].• Use a hot-start polymerase to prevent pre-PCR activity [15] [5]. |

| No Product (in conjunction with NTC contamination) | • Contamination of reagents with amplicons or foreign DNA [26] | • Implement spatial separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [26].• Use aerosol-resistant filter tips [26].• Decontaminate with 10% bleach and UV irradiation [26].• Employ Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG/UNG) to degrade carryover contaminants [26]. |

Advanced Optimization Experiment Protocol

If initial troubleshooting steps do not resolve the issue, a more rigorous optimization is required. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology.

Objective: To simultaneously optimize two critical factors for PCR specificity: Annealing Temperature and Mg2+ Concentration.

Materials:

- Target DNA template

- Forward and reverse primers

- Hot-start high-fidelity DNA polymerase and its compatible buffer

- dNTP mix

- MgCl2 or MgSO4 solution (concentration as per polymerase manufacturer)

- Nuclease-free water

- Thermal cycler with gradient functionality

Method:

- Prepare a Master Mix: Calculate volumes for a single 50 µL reaction multiplied by the total number of conditions to be tested plus 10% extra. Combine in order on ice [25]:

- Nuclease-free water (Q.S. to 50 µL)

- 10X PCR Buffer (5 µL)

- dNTP Mix (10 mM each) (1 µL)

- Template DNA (e.g., 1-100 ng)

- Hot-start DNA Polymerase (0.5-2.5 units)

Aliquot and Add Variables:

- Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes.

- Add Mg2+ to each tube to create a range of final concentrations (e.g., 1.0 mM, 1.5 mM, 2.0 mM, 3.0 mM).

- Add primers to each tube to a final concentration within the 0.1-1 µM range.

Thermal Cycling:

- Program the thermal cycler with a gradient annealing temperature across the block. Set the range to span 5-10°C below to 5°C above the calculated theoretical Tm of your primers [25] [5].

- Run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 30 sec.

- 35 Cycles:

- Denature: 98°C for 10 sec.

- Anneal: Gradient range for 30 sec.

- Extend: 72°C for 30 sec/kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min.

- Hold: 4°C.

Analysis:

- Analyze all reactions alongside a molecular weight standard on an agarose gel.

- The optimal condition is identified as the combination of annealing temperature and Mg2+ concentration that produces a single, bright band of the expected size with no visible primer-dimer or smearing.

This experimental workflow and the decision-making process for addressing non-specific amplification are summarized in the following diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their roles in preventing and resolving non-specific amplification.

Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Specific Amplification

| Reagent | Function in Troubleshooting | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [15] [5] | Remains inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. | The gold standard for improving specificity. Choose based on required fidelity and processivity. |

| Mg2+ (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) [5] [24] | Cofactor for DNA polymerase. Concentration directly affects primer annealing and enzyme fidelity. | Requires optimization. Excess Mg2+ reduces specificity; too little reduces yield. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine, BSA) [25] [5] | DMSO/Betaine help denature GC-rich templates; BSA can bind inhibitors and reduce non-specific adsorption. | Use at the lowest effective concentration (e.g., DMSO 1-10%, Betaine 0.5-2.5 M) as they can inhibit PCR [25]. |

| dNTP Mix [24] | Building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Use balanced, equimolar concentrations. Unbalanced dNTPs can increase error rate and affect Mg2+ availability. |

| UNG/UDG System [26] | Enzymatically degrades PCR products from previous reactions (carryover contamination) before amplification begins. | Critical for diagnostic and high-sensitivity applications to prevent false positives. |

| GC Enhancer [5] [24] | A specific formulation of additives that facilitates the amplification of difficult, GC-rich templates. | Often supplied with specific polymerase kits. More targeted than general additives like DMSO. |

Advanced PCR Methods to Enhance Specificity and Yield

Hot-Start PCR is a specialized molecular technique designed to suppress non-specific DNA amplification by keeping the DNA polymerase inactive until high temperatures are reached. In standard PCR, the polymerase retains some activity at room temperature, which can lead to mispriming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. These artifacts compete with the target amplification, reducing yield, specificity, and overall reaction efficiency. Hot-Start PCR effectively mitigates these issues by employing a mechanism that temporarily inhibits the polymerase until the first high-temperature denaturation step, thereby ensuring that amplification only begins under stringent conditions [27].

This guide provides a detailed framework for troubleshooting non-specific amplification, with a particular focus on implementing Hot-Start PCR methodologies to enhance the robustness and reproducibility of your experiments.

Troubleshooting Guide: Non-Specific Amplification

The table below summarizes the common causes and solutions for non-specific amplification in PCR, a primary issue that Hot-Start PCR is designed to address.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Non-Specific Amplification

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands or Smears | Primer annealing temperature is too low [28] [12] [5] | Increase annealing temperature in 1-2°C increments; use a gradient cycler. Optimize to 3-5°C below the primer Tm [5]. |

| Multiple Bands or Smears | Premature polymerase activity during setup [28] [29] | Use a Hot-Start DNA polymerase [28] [5] [29]. Set up reactions on ice with chilled components [28]. |

| Multiple Bands or Smears | Poor primer design [28] [12] [5] | Verify primer specificity and avoid complementarity. Use primer design software (e.g., Primer3) and perform in silico PCR [12]. |

| Multiple Bands or Smears | Excessive Mg2+ concentration [28] [12] [5] | Optimize Mg2+ concentration, testing in 0.2-1 mM increments. High Mg2+ promotes non-specific binding [28]. |

| Multiple Bands or Smears | Too many PCR cycles [12] [5] | Reduce the number of amplification cycles (generally 25-35 is sufficient) to prevent accumulation of non-specific products [12]. |

| Primer-Dimers | High primer concentration [28] [5] | Optimize primer concentration, typically within the range of 0.1-1 µM [28] [5]. For standard PCR, 10 pM is often effective [12]. |

| Primer-Dimers | Polymerase activity at low temperature [1] [29] | Employ a Hot-Start polymerase to prevent primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [29] [27]. |

| No Amplification | Overly stringent conditions / polymerase inactive | Ensure the Hot-Start polymerase is properly activated by following the manufacturer's recommended initial denaturation temperature and time. |

| Low Yield | Polymerase not fully activated or insufficient extension | Verify initial denaturation step for antibody-based Hot-Start enzymes. Optimize extension time and temperature [5]. |

Diagram 1: The Hot-Start PCR mechanism prevents non-specific amplification by keeping the polymerase inactive until the first high-temperature denaturation step.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental mechanism behind Hot-Start PCR?

Hot-Start PCR utilizes a modified DNA polymerase that is rendered inactive at room temperature. This is commonly achieved by binding the enzyme with a specific neutralizing antibody or a chemical modifier. During the initial high-temperature denaturation step of the PCR cycle (typically ≥94°C), the antibody is denatured or the chemical block is released, restoring full polymerase activity. This ensures the enzyme is only functional after the reaction mixture has been heated to temperatures that promote specific primer-template binding [29] [27].

How does Hot-Start PCR specifically reduce primer-dimer formation?

At room temperature, primers can bind to each other via complementary sequences (forming primer-dimers) or bind non-specifically to genomic DNA. If the polymerase is active during this stage, it will extend these misprimed complexes, creating unwanted amplification products that compete for reagents. Hot-Start PCR prevents this by completely inhibiting the polymerase until the reaction is heated, thereby eliminating any extension during the setup phase [29] [27].

My Hot-Start PCR still shows non-specific bands. What should I check?

Even with a Hot-Start enzyme, other factors can cause non-specificity. Your troubleshooting should include:

- Annealing Temperature: This is a common culprit. Use a temperature gradient on your thermocycler to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature for your primer-template pair [28] [5].

- Primer Design: Re-evaluate your primer sequences for specificity. Ensure they do not have complementary regions, especially at the 3' ends, and verify their binding specificity using in silico tools [12].

- Mg2+ Concentration: Excessive Mg2+ can reduce specificity. Titrate the Mg2+ concentration in your reactions to find the optimal level [28] [5].

- Template Quality and Quantity: Degraded DNA or too much template can lead to smearing and non-specific amplification. Re-assess template quality by gel electrophoresis and use the recommended amount (e.g., 10-100 ng for genomic DNA) [12] [5].

Can I set up Hot-Start PCR reactions at room temperature?

Yes, a key practical advantage of most modern Hot-Start polymerases (particularly antibody-based ones) is that they allow for reaction assembly at room temperature without compromising specificity. This is invaluable for high-throughput workflows [29].

What are the main types of Hot-Start modifications available?

The two primary methods are:

- Antibody-Based: A monoclonal antibody binds the polymerase's active site, blocking activity until it is denatured at high heat. This method offers rapid activation [29] [27].

- Chemical Modification: The polymerase is chemically blocked with thermo-labile groups. Activity is restored after a prolonged initial denaturation step that cleaves the modifiers [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their roles in optimizing Hot-Start PCR experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Hot-Start PCR Experiments

| Reagent | Function & Importance in Hot-Start PCR |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | The core component. Engineered to be inactive at room temperature to prevent pre-amplification mispriming and primer-dimer formation, thereby significantly enhancing specificity [29] [27]. |

| Optimized Reaction Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for polymerase activity after activation. Often includes components that help amplify complex templates like GC-rich regions [5]. |

| MgCl2 or MgSO4 | A critical cofactor for DNA polymerase. Its concentration must be optimized, as it directly affects enzyme activity, fidelity, and primer annealing specificity [28] [12] [5]. |

| PCR Enhancers/Co-solvents | Additives like DMSO, betaine, or GC enhancers can help denature difficult templates with high GC content or secondary structures, improving yield and specificity in conjunction with Hot-Start [5]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks for new DNA strands. Must be of high quality and used at balanced equimolar concentrations to prevent misincorporation errors that can accumulate during amplification [28] [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Annealing Temperature with Hot-Start PCR

Even with a Hot-Start enzyme, determining the correct annealing temperature (T_a) is critical for specific amplification. This protocol outlines how to use a gradient thermocycler for optimization.

Principle: A gradient thermocycler creates a temperature gradient across its block, allowing you to test a range of annealing temperatures in a single run. The optimal T_a is typically 3-5°C below the calculated melting temperature (T_m) of the primers [5].

Materials:

- Hot-Start PCR Master Mix (or individual components: Hot-Start polymerase, buffer, dNTPs)

- Template DNA

- Forward and Reverse Primers

- Nuclease-free water

- Gradient Thermocycler

Method:

- Prepare Master Mix: On ice, prepare a single PCR master mix for all reactions containing Hot-Start polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, primers, template, and water. Mix thoroughly.

- Aliquot: Dispense equal volumes of the master mix into the PCR tubes or plate wells that will be placed along the gradient block.

- Set Gradient Program: Program your thermocycler with a standard cycling protocol, but set the annealing step to a gradient. For example, if the calculated

T_mof your primers is 60°C, set a gradient from 55°C to 65°C. - Run PCR: Place the tubes in the thermocycler and start the program. A standard program includes:

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes (activates Hot-Start polymerase).

- Amplification Cycles (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Anneal: Gradient temperature for 15-30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C for 1 min/kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Analyze Results: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The well with the strongest target band and the absence of non-specific bands or smears indicates the optimal annealing temperature.

Diagram 2: Workflow for optimizing PCR annealing temperature using a gradient thermocycler to eliminate non-specific amplification.

Core Concepts and Mechanism

What is the fundamental principle behind Touchdown PCR?

Touchdown (TD) PCR is a modified PCR technique designed to increase amplification specificity and sensitivity by systematically lowering the annealing temperature during the cycling program. The process begins with an annealing temperature set higher than the optimal melting temperature (Tm) of the primers. Over a series of cycles (e.g., 10 cycles), this temperature is incrementally decreased (e.g., by 1°C per cycle) until it reaches a temperature below the calculated Tm. The remaining cycles then proceed at this lower, permissive temperature [30] [31]. This strategy ensures that in the initial cycles, only the most perfectly matched primer-template pairs can anneal, selectively enriching the reaction with the correct target. Once this specific product dominates, the reaction can continue at a more efficient, lower temperature without significant competition from non-specific products [30] [32].

How does Touchdown PCR improve specificity and yield?

The stepwise decrease in annealing temperature provides a dual advantage [30] [31] [33]:

- Early High-Temperature Cycles: The initial high annealing temperature promotes highly specific primer binding, minimizing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation. This gives the desired amplicon a critical "head start" [30] [32].

- Later Lower-Temperature Cycles: As the temperature drops to and below the optimal Tm, amplification efficiency and yield increase dramatically. Because the specific product is already the predominant DNA species, it is amplified preferentially over any potential non-specific products, resulting in a high yield of the correct amplicon [30] [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

The following table outlines frequent challenges encountered during standard PCR and how Touchdown PCR and related strategies can address them.

| Problem | Description | Solutions & How Touchdown PCR Helps |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific Amplification | Multiple unwanted bands or smears appear on a gel due to primers binding to incorrect sequences [34]. | • Increase Annealing Temperature: Touchdown PCR starts high to enforce stringent binding [34] [35].• Use Hot-Start Polymerase: Prevents enzyme activity during setup, reducing non-specific products [5] [32].• Reduce Primer/Template Concentration: Excess can promote mispriming [34] [5]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | Short, unwanted products from primers annealing to each other [15]. | • Touchdown PCR: High initial annealing temperature destabilizes primer-primer interactions [30] [32].• Optimize Primer Design: Check for complementarity between primers [5] [15]. |

| No or Low Yield | Little to no desired product is amplified. | • Touchdown PCR: Systematically finds the optimal annealing temperature, ensuring good yield in later cycles [30] [33].• Increase Number of Cycles: Up to 40 cycles for low-abundance targets [34].• Check Template Quality/Quantity: Ensure DNA is intact and of sufficient concentration [5]. |

| Smearing | A continuous smear of DNA on the gel instead of crisp bands. | • Reduce Cycle Number: Overcycling can cause smearing [34].• Use Touchdown PCR: Enhances specificity to prevent background smear [34].• Eliminate Contamination: Use separate pre- and post-PCR areas and reagents [34]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Touchdown PCR

Can you provide a detailed protocol for a standard Touchdown PCR?

The protocol below is a generalized example. Optimal temperatures and times may need adjustment based on your specific primers, polymerase, and template [31].

1. Reaction Setup

- Keep reactions on ice during setup to prevent non-specific priming before cycling begins [31].

- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to further suppress activity at low temperatures [31] [32].

- A sample master mix for a 50 µl reaction might contain:

- 1X PCR Buffer

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 0.1–1 µM of each primer (optimize concentration)

- 1–2 units of Hot-Start DNA Polymerase

- Template DNA (e.g., 10–100 ng genomic DNA)

- MgCl₂ (if not in buffer; concentration may require optimization)

2. Thermal Cycling Program This example assumes a primer Tm of 57°C [31].

| Stage | Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | Denature | 95°C | 3 min | 1 | Fully denature template and activate hot-start enzyme. |

| Stage 1: Touchdown | Denature | 95°C | 30 sec | 10 cycles | Denature template. |

| Anneal | 67°C (Tm+10) | 45 sec | High stringency: Selective amplification of specific target. | ||

| Extend | 72°C | 45 sec/kb | Synthesize new DNA strands. | ||

| Stage 2: Amplification | Denature | 95°C | 30 sec | 20–25 cycles | Denature template. |

| Anneal | 57°C (Calculated Tm) | 45 sec | Efficient amplification: Specific product is now dominant. | ||

| Extend | 72°C | 45 sec/kb | Synthesize new DNA strands. | ||

| Final Extension | Extend | 72°C | 5–15 min | 1 | Ensure all amplicons are full-length. |

The logical workflow and temperature profile of this protocol can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is crucial for success. The table below lists essential materials and their functions in optimizing Touchdown PCR.

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Importance in Touchdown PCR |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Critical. Remains inactive until high temperatures are reached, preventing non-specific primer extension during reaction setup and the initial low-temperature ramp. Dramatically improves specificity [5] [32]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, BSA, Betaine) | For difficult templates. Helps amplify GC-rich regions by destabilizing DNA secondary structures. Note: Additives can lower the effective primer Tm, which may need to be accounted for in the program [5] [31] [32]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Highly useful for optimization. Allows empirical determination of the optimal annealing temperature by running simultaneous reactions at different temperatures. Informs the starting and ending points for the touchdown program [5]. |

| Nested Primers | For extreme specificity issues. A second set of primers that bind within the first PCR product are used in a subsequent reaction. This greatly increases specificity and is a powerful tool if Touchdown PCR alone is insufficient [34] [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between Touchdown PCR and Stepdown PCR? Stepdown PCR is a simplification of Touchdown PCR. Instead of a gradual, cycle-by-cycle decrease in annealing temperature, Stepdown PCR uses fewer, steeper drops in temperature (e.g., 3 cycles at 62°C, 3 cycles at 58°C, then multiple cycles at 50°C). This makes it easier to program on older thermal cyclers that lack automated touchdown functionality while still providing a significant benefit in specificity and yield [30] [33].

When should I consider using Touchdown PCR? Touchdown PCR is particularly valuable in several scenarios [30] [31]:

- When you are unsure of the optimal annealing temperature for your primer-template combination.

- When you are using primers across different template sources (e.g., different species) where perfect matches are not guaranteed.

- When you are experiencing persistent non-specific amplification or primer-dimer formation with standard PCR protocols.

- When you have made modifications to the PCR without full re-optimization (e.g., added MgCl₂ or other additives).

My Touchdown PCR still shows non-specific bands. What can I do? If problems persist, consider these additional optimizations [34] [5] [31]:

- Combine with Hot-Start: Ensure you are using a robust hot-start polymerase.

- Adjust the Touchdown Parameters: Use more cycles in the touchdown phase or decrease the temperature in smaller increments (e.g., 0.5°C per cycle).

- Optimize Reagent Concentrations: Titrate Mg²⁺ and primer concentrations, as excess can promote non-specific binding.

- Use Additives: Incorporate DMSO, formamide, or GC enhancers for difficult templates.

- Keep Cycle Numbers in Check: Limit the total number of cycles (e.g., to below 35) to prevent the accumulation of non-specific products in later cycles.

- Redesign Primers: Verify primer specificity using BLAST and check for self-complementarity.

Why Do My PCR Reactions Fail? A Primer Design FAQ

FAQ 1: I get no PCR product at all. What went wrong with my primers?

Several primer-related issues can lead to a complete failure of amplification.

- Poor Primer Specificity: Verify that your primer sequences are an exact match to your intended target template [36].

- Suboptimal Annealing Temperature: The annealing temperature (

T_a) may be too high. Recalculate the melting temperature (T_m) of your primers and test an annealing temperature gradient, starting at approximately 5°C below the lowerT_mof the primer pair [36]. - Low Primer Concentration: Ensure the primer concentration in the reaction is typically between 0.05–1 µM. Too little primer will prevent efficient binding [37] [36].

- Primer Degradation: Aliquot primers to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can lead to degradation. If PCR assays that previously worked suddenly fail, suspect primer degradation [37].

FAQ 2: My gel shows multiple bands or a smear instead of one clean product. How can I improve specificity?

Non-specific amplification is often due to primers binding to unintended sites.

- Increase Annealing Temperature: A low annealing temperature is a common cause. Increase the temperature in increments to promote more specific binding [36] [15].

- Check for Mispriming: Use software tools to verify your primers do not have complementary regions elsewhere in the template DNA [36].

- Avoid GC-Rich 3' Ends: Primers ending in stretches of G or C bases can bind non-specifically. Re-design primers to have a balanced 3' end [36].

- Use a Hot-Start Polymerase: These enzymes are inactive at room temperature, preventing premature priming during reaction setup and reducing non-specific products [36] [15].

- Optimize Mg²⁺ Concentration: Adjust the magnesium chloride concentration in 0.2–1 mM increments, as it can affect priming specificity [36].

FAQ 3: What is a "primer-dimer" and how do I prevent it?

Primer-dimer is a short, double-stranded artifact formed when primers anneal to each other due to complementarity, especially at their 3' ends, and are extended by the polymerase [37] [15]. It consumes reaction reagents and competes with the desired product.

- Check for Self-Complementarity: Use oligonucleotide analysis tools to screen primers for self-dimers and cross-dimers. The ΔG value for any dimer should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol [38].

- Optimize Primer Concentration: High primer concentrations increase the risk of primer-dimer formation [37].

- Re-design Primers: Avoid complementarity between the two primers, particularly at the 3' ends, which is critical for extension [37] [39].

The table below consolidates key quantitative parameters for designing effective PCR primers.

Table 1: Optimal Design Parameters for Standard PCR Primers

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Rationale & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides [37] [38] | Balances specificity (longer) with efficient annealing and cost (shorter). 18–24 bp is often ideal for specificity [39]. |

Melting Temperature (T_m) |

60–64°C (ideal ~62°C) [38] | The temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates. Determines the annealing temperature [40]. |

Annealing Temperature (T_a) |

≤ 5°C below primer T_m [38] |

The actual reaction temperature. Set no more than 5°C below the lower T_m of the primer pair [38] [36]. |

T_m Difference (Pair) |

≤ 2–5°C [38] [39] | Ensures both primers anneal to the template simultaneously and efficiently. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [37] [40] | Provides sufficient binding strength (GC bonds are stronger than AT) without promoting non-specific binding. |

| GC Clamp | Avoid >3 G/C in last 5 bases at 3' end [40] | Prevents non-specific binding caused by overly stable 3' ends, which is critical for initiation of synthesis [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: In Silico Primer Design and Validation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for designing and computationally validating primers before synthesis.

1. Define the Target and Gather Sequences

- Identify the exact genomic region, gene, or sequence you intend to amplify.

- Obtain the complete template sequence(s) in FASTA format from a reliable database (e.g., NCBI Nucleotide). If working with multiple related sequences (e.g., from different species), create a multiple sequence alignment.

2. Select Primer Binding Sites

- Amplicon Length: For standard PCR, aim for a product between 70–150 bp for easy amplification. For cloning or other applications, products up to 500 bp or more are possible but may require longer extension times [38].

- Avoid Secondary Structures: Ensure the selected binding sites are not located in regions of the template that are prone to forming stable secondary structures, which can block primer access [37].

- Span Exon-Exon Junctions (for qPCR): When working with cDNA, design primers to span an exon-exon junction. This ensures the amplification of spliced mRNA and prevents false positives from contaminating genomic DNA [38].

3. Apply Design Criteria and Use Design Tools

- Input your target sequence into a dedicated primer design software (e.g., Primer3, NCBI Primer-BLAST, or commercial tools from IDT or Eurofins Genomics) [38] [40] [41].

- Configure the software parameters using the values from Table 1 (e.g., Primer

T_m: 60–64°C, GC%: 40–60%, Product Size: 70–150 bp). - Generate several candidate primer pairs for evaluation.

4. Validate Candidate Primers In Silico

- Check for Secondary Structures: Analyze each candidate primer for hairpins and self-dimers using a tool like the IDT OligoAnalyzer. Avoid primers with stable secondary structures (ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol) [38].

- Check for Cross-Dimerization: Analyze the forward and reverse primer together for heterodimer formation [38].

- Verify Specificity with BLAST: Perform a nucleotide BLAST (NCBI) search for each primer sequence against the appropriate genome database to ensure it is unique to your intended target and lacks significant homology to off-target sequences [38] [39].

5. Final Selection and Ordering

- Select the primer pair that best fulfills all design criteria and shows no significant secondary structures or off-target homology.

- Order primers from a reputable supplier with HPLC or equivalent purification to minimize truncated sequences and impurities [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for PCR and Primer-Related Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Troubleshooting Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | DNA synthesis with superior accuracy, reducing sequence errors [36]. | Essential for cloning, sequencing, or any downstream application where sequence integrity is critical. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Polymerase is inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming during reaction setup [36] [15]. | First-line solution for reducing non-specific bands and primer-dimer formation. |

| GC Enhancer / Additives (e.g., Betaine, DMSO) | Disrupts secondary structures in GC-rich templates, improving polymerase processivity and yield [36]. | Use when amplifying difficult, GC-rich targets (>60% GC) to prevent dramatic drops in yield or complete failure. |

| dNTP Mix | The four nucleotide building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. | Use fresh, balanced mixes to prevent incorporation errors and failed reactions [36]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Cofactor essential for DNA polymerase activity. Concentration directly affects primer annealing and specificity [38] [36]. | A key optimization variable. Adjust in 0.2–1 mM increments to resolve issues with no product, non-specific bands, or primer-dimer. |

| PCR Clean-Up Kit | Purifies PCR products from primers, enzymes, salts, and dNTPs. | Essential for downstream applications like sequencing or cloning. Also used to remove potential inhibitors from a template before a new PCR [36]. |

Within the framework of advanced PCR troubleshooting research, achieving clean, specific amplification hinges on the precise optimization of core reaction components. The interplay between Mg2+ concentration, dNTP balance, and DNA polymerase selection forms a thermodynamic system that directly controls reaction stringency, fidelity, and efficiency. Suboptimal conditions in any of these three areas are primary contributors to non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, and erroneous products, which can critically compromise downstream applications in cloning, sequencing, and diagnostic assay development. This guide synthesizes empirical data and recent predictive modeling to provide a systematic approach to optimizing these key parameters.

Magnesium Ion (Mg2+) Optimization

Role and Mechanism

Magnesium ions (Mg2+) serve as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. They facilitate the formation of phosphodiester bonds by stabilizing the transition state during dNTP incorporation and help neutralize the negative charges on the DNA backbone, promoting primer-template binding [42]. The free Mg2+ concentration, which is not chelated by dNTPs or EDTA, is the critical variable.

Quantitative Optimization Guidelines

The optimal Mg2+ concentration is interdependent with dNTP concentration and must be optimized empirically. The table below summarizes the effects of Mg2+ concentration and provides a titration protocol.

Table 1: Mg2+ Concentration Optimization Guide

| Condition | Effect on PCR | Recommended Action | Typical Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Low | No PCR product; polymerase activity severely reduced [43] [5]. | Increase concentration in 0.2 - 0.5 mM increments [44] [43]. | 1.5 - 2.0 mM for Taq Polymerase [43]. |

| Too High | Non-specific amplification; smeared bands; reduced fidelity [44] [5] [45]. | Decrease concentration in 0.2 - 0.5 mM increments. | Up to 4 mM, titrated as needed [43]. |

| Optimal | High specificity and yield. | Use as a baseline for further fine-tuning. |

Advanced Modeling and Experimental Protocol

Recent research employs multivariate Taylor series expansion and thermodynamic integration to predict optimal MgCl2, achieving a predictive R² value of 0.9942 [46]. The model highlights the significant influence of dNTP-primer interactions (28.5% relative importance) and GC content (22.1%) on the required Mg2+ level [46].

Experimental Titration Protocol:

- Prepare a Master Mix containing all standard PCR components except Mg2+ and template.

- Aliquot the master mix into 5-8 PCR tubes.

- Spike each tube with MgCl₂ to create a concentration gradient (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0 mM).

- Add template to each tube and run the PCR.

- Analyze results by gel electrophoresis to identify the concentration yielding the strongest specific product with minimal background.

Mg2+ Optimization Workflow

Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs) Optimization

Role and Mechanism

dNTPs are the building blocks for new DNA strand synthesis. Unbalanced dNTP concentrations are a major source of base misincorporation, which reduces amplification fidelity and can lead to sequence errors in the final product [44] [5].

Quantitative Optimization Guidelines

The concentration of dNTPs is directly linked to Mg2+ optimization, as Mg2+ binds to dNTPs in the reaction.

Table 2: dNTP Concentration Optimization Guide

| Condition | Effect on PCR | Recommended Action | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Low | Reduced yield; premature reaction termination [42]. | Increase concentration of all four dNTPs equally. | 200 µM of each dNTP is standard [43] [42]. |

| Too High | Reduced fidelity; increased misincorporation; can chelate Mg2+, causing apparent Mg2+ deficiency [43] [42]. | Decrease dNTP concentration. | 50-100 µM can enhance fidelity [43]. |

| Unbalanced | Increased PCR error rate and low fidelity [44] [5]. | Use prepared dNTP mixes or ensure fresh, equimolar stocks. | Always use equimolar concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP. |

| High Fidelity Need | Higher accuracy, but may reduce yield. | Use lower dNTP (50-100 µM) and proportionally lower Mg2+ [42]. |

DNA Polymerase Selection

Types and Characteristics

The choice of DNA polymerase is arguably the most critical decision for PCR success, impacting specificity, yield, fidelity, and the ability to amplify complex templates.

Polymerase Selection Guide

Table 3: DNA Polymerase Selection Guide

| Polymerase Type | Key Features | Best For | Fidelity (Error Rate) | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Taq | Thermostable, low cost, generates dA-overhangs. | Routine, low-fidelity amplification of simple templates (<5 kb) [43]. | Low (~1 x 10⁻⁴ errors/bp) | NEB Taq [43] |

| Hot Start | Inactive at room temperature, activated by heat. Prevents non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation [44] [5] [15]. | High-specificity reactions; multiplex PCR. | Varies by base enzyme. | OneTaq Hot Start [44], PrimeSTAR HS [45] |

| High-Fidelity | Possesses 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity. | Cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis [5]. | High (~1 x 10⁻⁶ errors/bp) | Q5 (NEB) [44], Phusion [44], Pfu |

| Long-Range | Engineered for processivity and stability. | Amplifying long targets (>5 kb) [44] [5]. | Varies. | LongAmp Taq (NEB) [44], Takara LA Taq [45] |

| High-GC/Complex | Often includes specialized buffers with enhancers. | GC-rich templates, complex secondary structures [44] [5] [45]. | Varies. | Q5 High-Fidelity [44], OneTaq [44] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase Mix | For applications requiring high accuracy and low error rates. | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0491) [44] |

| Hot Start Polymerase | To suppress non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. | OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0481) [44] |

| PCR Clean-up Kit | To purify template DNA or PCR products from contaminants like salts or enzymes. | Monarch PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit (NEB #T1130) [44] |

| dNTP Mix | Provides pre-mixed, quality-controlled equimolar solutions of all four dNTPs. | Various suppliers (NEB, Thermo Fisher) |

| GC Enhancer / Additives | To aid in denaturing GC-rich templates and resolving secondary structures. | Included with some polymerases (e.g., for Q5, OneTaq) [44] [5] |

| Template Repair Mix | To repair damaged template DNA (e.g., nicked, deaminated bases). | PreCR Repair Mix (NEB #M0309) [44] |

Integrated Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My PCR gel shows multiple non-specific bands. What should I adjust first?

This is a classic symptom of low reaction stringency. A systematic approach is best:

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Start by increasing the temperature in 2°C increments [45] [47].

- Optimize Mg2+: High Mg2+ can cause non-specific binding. Titrate downwards from your current concentration in 0.2-0.5 mM steps [44] [2].

- Switch Polymerase: Use a Hot-Start enzyme to prevent activity during setup [44] [5] [15].

- Check Component Concentrations: Ensure you are not using excessive template, primers, or polymerase [43] [42].

FAQ 2: I am getting a good yield but my sequencing results show mutations. How can I improve fidelity?

Sequence errors are often related to polymerase fidelity and reaction conditions.

- Use a High-Fidelity Polymerase: Switch from Taq to a proofreading enzyme like Q5 or Pfu [44] [5].

- Lower dNTP Concentrations: Use 50-100 µM of each dNTP to enhance fidelity [43].

- Reduce Mg2+ Concentration: Excessive Mg2+ can reduce fidelity [5] [45].

- Minimize Cycle Number: Use the minimum number of cycles necessary to obtain sufficient product [44] [5].

FAQ 3: How do I optimize PCR for a GC-rich template?

GC-rich sequences (>65%) form stable secondary structures that impede polymerase progression.

- Use a Specialized Polymerase: Select an enzyme formulated for GC-rich templates, such as Q5 or OneTaq [44] [45].

- Add Enhancers: Use GC enhancers or co-solvents like DMSO, betaine, or formamide included in specialized buffers [5].

- Adjust Thermocycling: Increase the denaturation temperature and/or time to ensure complete melting of the template [5].

Troubleshooting Non-Specific Bands

Using Additives and Enhancers for Difficult Templates (GC-Rich, Long Amplicons)