Particle Swarm Optimization for Molecular Clusters: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Materials Design

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for predicting the structure and properties of molecular clusters, a critical task in drug discovery and materials science.

Particle Swarm Optimization for Molecular Clusters: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Materials Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for predicting the structure and properties of molecular clusters, a critical task in drug discovery and materials science. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational theory of PSO and its fit within the global optimization landscape for complex molecular potential energy surfaces. The guide details advanced methodological adaptations and hybrid frameworks, such as HSAPSO, that enhance PSO for pharmaceutical applications. It further addresses prevalent challenges like premature convergence and parameter sensitivity, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents validation protocols and comparative analyses with other global optimization methods, equipping scientists with the knowledge to effectively implement PSO for accelerating molecular design and development.

Understanding PSO and Molecular Cluster Optimization

In computational chemistry and drug development, a central problem is finding the most stable, low-energy structure of a molecule or molecular cluster. This process, known as molecular global optimization, requires identifying the global minimum on the system's Potential Energy Surface (PES) [1] [2]. The PES represents the energy of a molecular system as a function of the positions of its atoms. While deep local minima correspond to stable molecular conformations, the global minimum dictates the most stable configuration and its resulting physical and chemical properties [1].

This task is exceptionally challenging because the PES for any system with more than a few atoms is typically highly multidimensional and characterized by a vast number of local minima that increase exponentially with the number of atoms [1] [3]. These local minima trap traditional local descent optimization algorithms, preventing them from finding the true global minimum. In molecular cluster research, this problem is paramount, as the structure with the lowest potential energy corresponds to the most stable configuration, which is essential for understanding the cluster's properties [3]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting and guidance for researchers employing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to overcome these challenges.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PSO Issues in Molecular Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our PSO simulation for a carbon cluster is converging to a structure that is known to be a local minimum, not the global minimum. What parameters should we adjust?

A: Premature convergence is a common issue. First, verify your swarm size; for small clusters (n<20), a swarm size of 20-40 particles is often sufficient [3] [4]. If it's too small, the search space is inadequately explored. Second, adjust the cognitive (c1) and social (c2) parameters to better balance exploration and exploitation. Try reducing c2 to limit the pull toward the current global best and increasing c1 to strengthen individual particle exploration [4]. Finally, consider implementing a modified PSO algorithm that incorporates a "velocity clamping" mechanism or combines PSO with a local search method like basin-hopping to escape local minima [3] [4].

Q2: The computational cost of our PSO calculation, which uses DFT for single-point energy calculations, is becoming prohibitive for clusters larger than 10 atoms. Are there any alternatives?

A: Yes, a two-stage strategy is highly recommended. First, use a PSO algorithm coupled with a computationally inexpensive harmonic or Hookean potential to perform the initial global minimum search [3]. This model treats atoms as spheres connected by springs, allowing for rapid evaluation of many candidate structures. Once the PSO identifies a low-energy candidate structure using this fast potential, you can then perform a final geometry optimization and single-point energy calculation using a higher-level method like DFT on only the most promising candidates [3] [4]. This hybrid approach significantly reduces the overall computational cost.

Q3: How can we enforce physical constraints, such as minimum van der Waals separation distances between atoms, within our PSO simulation?

A: Incorporating constraints requires modifying the algorithm. One effective atom-based approach reduces dimensionality and allows for tractable enforcement of constraints while maintaining good global convergence properties [5]. This can be implemented by adding a high-energy penalty to the objective function (the potential energy) whenever a candidate structure violates a constraint. The penalty should be large enough to make invalid solutions unfavorable to the swarm [5]. Ensure that the initial swarm is also generated to satisfy all known physical constraints to provide a better starting point for the search.

Common Error Messages and Solutions

The table below summarizes specific runtime issues, their likely causes, and corrective actions.

Table: Common PSO Implementation Errors and Solutions

| Error / Symptom | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence to a high-energy, non-physical structure. | Inaccurate or divergent potential energy calculations from the electronic structure software (e.g., Gaussian). | Check the Gaussian output logs for convergence warnings. Tighten the convergence criteria for the SCF calculation. Consider using a different initial geometry guess [4]. |

| PSO particles "exploding" to coordinates with unrealistically large values. | Uncontrolled particle velocities. | Implement velocity clamping to restrict the maximum velocity in each dimension [4]. Review and reduce the inertia weight (ω) parameter. |

| The algorithm fails to find structures close to a known global minimum. | Swarm diversity loss or insufficient exploration. | Increase the swarm size. Restart the simulation with different random seeds. Consider using a niching PSO variant to maintain sub-populations in different regions of the PES [4]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and theoretical constructs essential for conducting PSO-based molecular optimization research.

Table: Essential "Reagents" for Molecular Global Optimization

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) | A hyper-dimensional surface mapping the system's energy as a function of all atomic coordinates. It is the fundamental landscape on which optimization occurs [2]. |

| Harmonic (Hookean) Potential | A computationally efficient model that approximates atomic interactions as springs obeying Hooke's law. Used for rapid pre-screening of candidate structures [3]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A high-accuracy quantum mechanical method used for final energy evaluation and geometry refinement of promising candidate structures identified by PSO [3] [4]. |

| Basin-Hopping (BH) Algorithm | A stochastic global optimization method that combines Monte Carlo moves with local minimization. Often used as a benchmark or in hybrid approaches with PSO [3]. |

| Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) | A pair of molecules differing by a single, small chemical transformation. Used to build knowledge-based rules for molecular optimization [6]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Global Optimization Methods

The performance of optimization algorithms can vary significantly based on the system. The table below provides a generalized comparison of methods commonly used for molecular cluster optimization.

Table: Comparison of Global Optimization Methods for Molecular Clusters

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Computational Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Population-based stochastic search inspired by social behavior [4]. | Moderate to High (when coupled with DFT) | Rapidly exploring vast search spaces and locating promising regions [3] [4]. |

| Basin-Hopping (BH) | Stochastic search that transforms the PES into a set of "basins" [3]. | Moderate to High | Effectively escaping deep local minima and refining low-energy structures [3]. |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | Probabilistic technique inspired by the annealing process in metallurgy [4]. | Moderate | Systems where a gradual, controlled search is effective. |

| Deterministic Methods (e.g., Branch-and-Bound) | Uses domain partitioning and Lipschitz constants to guarantee global convergence [1]. | Very High (exponential scaling) | Small systems (n ≤ 5) where a guaranteed global minimum is required [1]. |

| Extended Cutting Angle Method (ECAM) | A deterministic method building saw-tooth underestimates of the PES [1]. | Very High | Low-dimensional problems where deterministic guarantees are needed [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol: PSO with DFT for Cluster Structure Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for finding the global minimum structure of a molecular cluster using a hybrid PSO-DFT approach [3] [4].

- System Definition: Define the cluster composition (e.g., C₁₀, WO₆⁶⁻).

- PSO Parameter Initialization:

- Set the swarm size (e.g., 20-40 particles).

- Define the cognitive (c1) and social (c2) parameters. Common starting values are c1 = c2 = 2.0.

- Set the inertia weight (ω), often between 0.4 and 0.9.

- Define the maximum number of iterations.

- Initial Swarm Generation: Randomly generate an initial population of cluster structures within a reasonable geometric boundary.

- Energy Evaluation (Hookean Potential): For each particle (cluster structure) in the swarm, calculate the potential energy using a fast harmonic potential function [3].

- PSO Core Loop: Iterate until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., no improvement in global best after a set number of iterations).

a. Update Personal and Global Bests: For each particle, compare its current energy to its personal best (

pbest) and the swarm's global best (gbest). Update them if a lower energy is found. b. Update Velocity and Position: For each particle, calculate its new velocity based on its previous velocity, its distance topbest, and its distance togbest. Use the new velocity to update the particle's position in 3N-dimensional space [3]. - Candidate Selection: Select the top K lowest-energy structures found by the PSO algorithm.

- High-Level Refinement: Perform a final geometry optimization and single-point energy calculation on the selected candidate structures using DFT software (e.g., Gaussian 09) [3] [4].

- Validation: Compare the predicted global minimum structure and its properties with experimental data (e.g., from X-ray diffraction) if available [3].

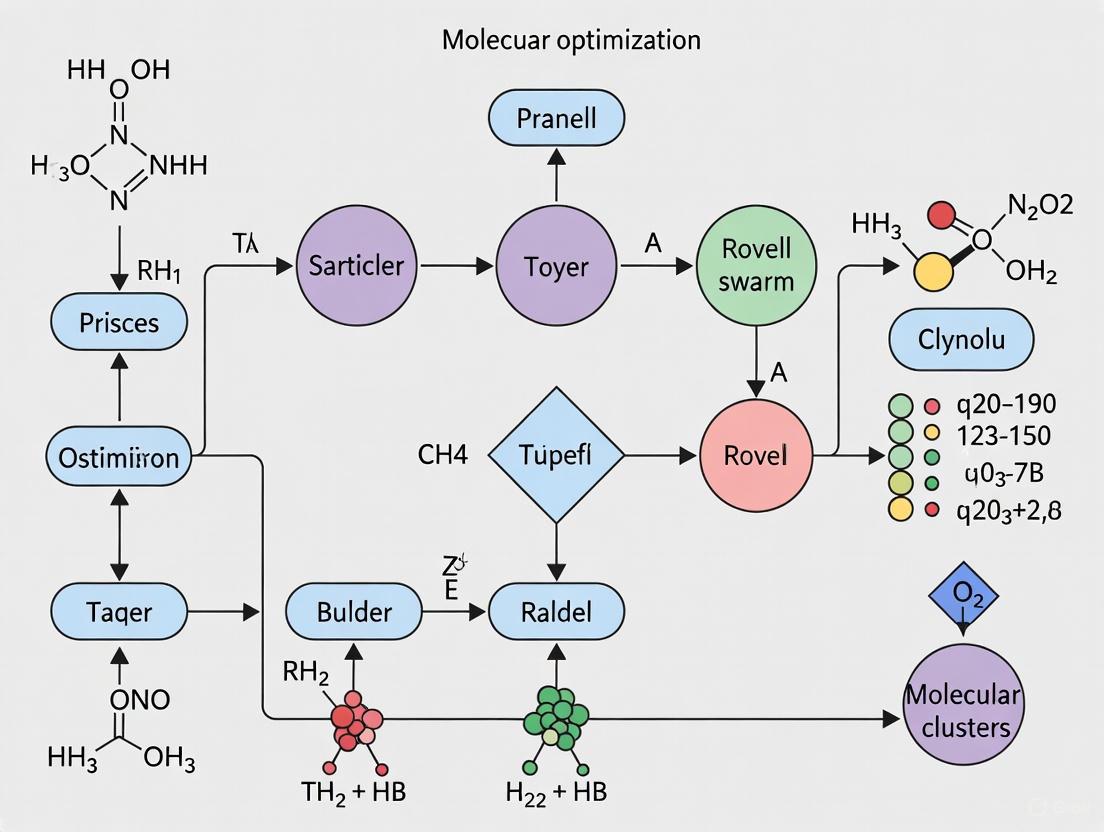

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow and iterative nature of the PSO algorithm for molecular cluster optimization.

PSO Workflow for Molecular Clusters

PES Navigation Strategy

Understanding the energy landscape is crucial for effective troubleshooting. The following diagram conceptualizes the challenge of navigating a complex PES and the role of PSO.

Navigating the PES with PSO

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a powerful meta-heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the collective intelligence of social swarms observed in nature, such as bird flocking and fish schooling [7] [8]. It was originally developed in the mid-1990s by Kennedy and Eberhart [8] [9]. The algorithm operates by maintaining a population of candidate solutions, called particles, which navigate the problem's search space [8]. Each particle adjusts its movement based on its own personal best-found position (pBest) and the best-known position found by the entire swarm (gBest), effectively balancing individual experience with social learning [7] [10].

The following table summarizes the key components that govern the behavior and performance of the PSO algorithm.

| Component | Symbol | Role & Influence on Algorithm Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Inertia Weight | w | Balances exploration & exploitation. High weight promotes global exploration; low weight favors local exploitation [7]. |

| Cognitive Coefficient | c1 | Determines a particle's attraction to its own best position (pBest). Higher values encourage individual learning [7]. |

| Social Coefficient | c2 | Determines a particle's attraction to the swarm's best position (gBest). Higher values promote social collaboration [7]. |

| Swarm Size | S | Affects diversity & convergence speed. Larger swarms cover more space but increase computational cost [7] [8]. |

| Position | xi | Represents a potential solution to the optimization problem in the search-space [8]. |

| Velocity | vi | Determines the direction and speed of a particle's movement in the search-space [8]. |

Biological Inspiration and Swarm Intelligence

PSO is grounded in the concept of Swarm Intelligence (SI), a sub-field of Artificial Intelligence that models the collective, decentralized behavior of social organisms [9]. The algorithm is a direct simulation of a simplified social system, originally intended to graphically simulate the graceful and unpredictable choreography of a bird flock [10].

In nature, the observable vicinity of a single bird is limited. However, by functioning as a swarm, the birds collectively gain awareness of a much larger area, increasing their chances of locating food sources [10]. PSO mathematically models this phenomenon. Each particle in the swarm is like an individual bird. While a particle has limited knowledge on its own, it can share information with its neighbors. Through a combination of its own discoveries and the shared knowledge of the swarm's success, the collective group efficiently navigates the complex search-space (or "fitness landscape") to find optimal regions [7] [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: Why is my PSO simulation converging to a local optimum instead of the global optimum in my complex molecular energy landscape?

This is a common challenge known as premature convergence [7] [9]. The complex, high-dimensional Potential Energy Surfaces (PES) of molecular systems are characterized by a vast number of local minima, making this a significant risk [11].

- Potential Cause 1: Poor parameter tuning. An inertia weight (w) that is too low or social coefficients (c2) that are too high can cause the swarm to converge too quickly.

- Solution: Increase global exploration by raising the inertia weight or adjusting the cognitive and social coefficients. A typical starting point is to set c1 and c2 both to 2, with an inertia weight starting near 0.9 and linearly decreasing over iterations [7] [8].

- Potential Cause 2: The swarm topology is causing rapid information spread. The standard global best (gbest) topology can lead to all particles rushing toward the first good solution found.

- Solution: Switch to a local best (lbest) topology, such as a ring topology, where particles only share information with their immediate neighbors. This slows convergence and improves exploration [8].

- Advanced Solution: Consider using an adaptive PSO (APSO) variant, which can automatically control parameters like the inertia weight during the run to help the swarm jump out of local optima [8] [9].

Q2: The convergence of my PSO is unacceptably slow for high-dimensional molecular structure predictions. How can I improve its efficiency?

Slow convergence is a recognized limitation of PSO, particularly in high-dimensional search-spaces [9] [10].

- Strategy 1: Hybridization. Combine PSO with a powerful local search algorithm. The PSO performs a global exploration to identify promising regions, and a local search method (e.g., a gradient-based quasi-Newton method) is then used to perform a refined, efficient search within that region [9] [11]. This is a common two-step process in molecular global optimization [11].

- Strategy 2: Parameter Tuning. Ensure your swarm size and maximum iterations are sufficient for the problem complexity. As a guideline, a balanced approach with 20–40 particles and 1000–2000 iterations is a good starting point [7].

- Strategy 3: Algorithm Selection. Explore more recent PSO variants designed for efficiency, such as Adaptive PSO (APSO), which features better search efficiency and higher convergence speed than the standard algorithm [8].

Q3: How does PSO compare to other global optimization methods like Genetic Algorithms (GA) for molecular cluster problems?

Both PSO and GA are population-based meta-heuristics, but they have different strengths.

- Simplicity: PSO is often favored for its simplicity and ease of implementation, with fewer parameters to tune compared to GA [7] [9].

- Information Sharing Mechanism: In GA, individuals share information across the entire population through crossover. In PSO, information is shared through the global best (gBest) or local best (lBest) particles, leading to a more directional and often faster convergence [7].

- Performance: Some studies have shown PSO to outperform GA in terms of convergence rate and accuracy for certain optimization problems [7]. For molecular structure prediction, both are established stochastic methods, and the choice may depend on the specific system and implementation [11]. Hybrid approaches that incorporate evolutionary operators from GA into PSO have also been developed to avoid local optima [9].

Standard Experimental Protocol for Molecular Cluster Optimization

The following workflow diagrams a standard protocol for applying PSO to a molecular cluster global optimization problem, reflecting the common two-step process in the field [11].

Detailed Methodology:

Problem Definition:

- Fitness Function: The potential energy of the molecular cluster, calculated using a chosen method (e.g., Density Functional Theory (DFT), force fields, or other quantum chemical methods). The goal is to find the geometry that minimizes this energy [11].

- Search-Space: Define the boundaries for atomic coordinates. Each particle's position vector (xᵢ) represents the full set of atomic coordinates for a candidate cluster structure.

Initialization:

- Swarm Generation: Randomly initialize a population (swarm) of S particles. Each particle's position is a randomly generated molecular geometry within the defined search-space [8] [11].

- Velocity: Initialize each particle's velocity randomly.

- Parameters: Set the inertia weight (w), cognitive (c1), and social (c2) coefficients.

Iterative Optimization:

- Fitness Evaluation: For each particle, calculate the potential energy of its molecular geometry using the chosen computational method. This is the most computationally expensive step [11].

- Update Bests: Compare the current energy to the particle's personal best (pBest) and the swarm's global best (gBest). Update these values if a better (lower energy) structure is found.

- Update Velocity and Position: Use the standard PSO update equations to move each particle through the search-space of molecular geometries [7] [8]. The velocity update considers the particle's previous momentum, its memory of its best structure, and the influence of the swarm's best-known structure.

Termination and Refinement:

- Convergence Check: The loop continues until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations, no improvement in gBest for a set number of steps, or finding a satisfactory solution) [8].

- Local Refinement: The putative global minimum structure identified by PSO is typically used as a starting point for a local optimization algorithm. This "refinement" step ensures the structure is a true local minimum on the PES and provides highly accurate energy and properties [11].

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for implementing PSO in molecular cluster research.

| Item / Resource | Category | Function in PSO for Molecular Clusters |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) | Conceptual Framework | A multidimensional hypersurface mapping the potential energy of a system as a function of its nuclear coordinates. The PES is the "fitness landscape" that PSO navigates to find the global minimum [11]. |

| Fitness Function (e.g., DFT Code) | Computational Tool | The core function PSO seeks to minimize. In molecular modeling, this is typically a quantum mechanics code (e.g., for DFT) that calculates the energy for a given atomic configuration [11]. |

| Initial Population Generator | Algorithmic Component | Software that creates random, physically reasonable initial cluster geometries to form the starting swarm, ensuring broad exploration of the search-space [11]. |

| Local Optimizer | Algorithmic Component | A local search algorithm (e.g., quasi-Newton methods) used for the final refinement of the PSO-identified solution to a precise local minimum [11]. |

| Inertia Weight (w) | PSO Parameter | Controls the particle's momentum, critically balancing the trade-off between exploring new regions of the PES and exploiting known promising areas [7] [8]. |

Why PSO for Molecular Clusters? Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for molecular cluster prediction?

PSO is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by the collective behavior of bird flocks or fish schools [12] [13]. In the context of molecular clusters, a group of particles (each representing a potential cluster structure) moves through the multi-dimensional potential energy surface (PES) [11]. Each particle is guided by its own best-known position (personal best, pbest) and the best-known position discovered by the entire swarm (global best, gbest) [3] [12]. This social learning strategy allows the swarm to collectively search for the global minimum energy configuration, which corresponds to the most stable structure of the molecular cluster [3] [14].

Q2: Why is PSO often more effective than traditional local optimization methods for this problem?

Traditional local optimization methods, such as gradient descent, are designed to find local minima and are highly dependent on the initial starting geometry [11]. They often become trapped in the nearest local minimum on the complex PES and cannot explore the landscape globally. In contrast, PSO's population-based approach allows it to explore a much larger area of the PES simultaneously [14] [13]. Its inherent stochasticity helps it to escape local minima and progressively narrow the search towards the global minimum, making it uniquely suited for navigating the exponentially growing number of local minima found in the energy landscapes of atomic and molecular clusters [11] [3].

Q3: How does PSO compare to other global optimization methods like Genetic Algorithms (GA) or Simulated Annealing (SA)?

While GA, SA, and PSO are all powerful global optimization methods, they differ in their fundamental strategies. GA relies on evolutionary principles of selection, crossover, and mutation, which can be computationally expensive due to the genetic operations on structures [11] [13]. SA uses a probabilistic acceptance criterion for new states based on a cooling schedule. PSO, however, operates on a simpler principle of social interaction, where particles share information and adjust their trajectories directly towards promising regions [13]. This often leads to faster convergence and a better balance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas) [14]. Studies have shown that PSO can be superior to other evolutionary methods like SA and Basin-Hopping (BH) for finding the global minimum energy structures of small carbon clusters [14].

Q4: What are the key parameters in a PSO algorithm that need tuning for molecular cluster optimization?

The performance of a PSO algorithm is highly influenced by several key parameters, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Particle Swarm Optimization

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Particles | The size of the swarm (population). | A larger swarm explores more thoroughly but increases computational cost [13]. |

| Inertia Weight (ω) | Controls the influence of the particle's previous velocity. | A high value promotes exploration; a low value favors exploitation [15] [13]. |

| Cognitive Coefficient (c1) | Controls the attraction to the particle's own best position (pbest). |

A high value encourages independent exploration of each particle [13]. |

| Social Coefficient (c2) | Controls the attraction to the swarm's global best position (gbest). |

A high value causes particles to converge more quickly on gbest [13]. |

| Swarm Topology | The communication network between particles (e.g., fully connected, ring). | Affects how information is spread, influencing the speed of convergence and diversity [13]. |

Q5: A common issue is premature convergence, where the swarm gets stuck in a local minimum. What strategies can mitigate this?

Premature convergence is a well-known challenge in PSO, where the swarm loses diversity and stagnates in a suboptimal region [15] [16]. Several advanced strategies have been developed to address this:

- Dynamic Sub-swarms (subswarm-PSO): The swarm is dynamically divided into sub-swarms based on particle fitness. The worst-performing half of the particles can be reinitialized randomly in each iteration, which continuously injects new diversity into the search and improves global exploration [15].

- Dimension-Wise Diversity Control (ELPSO-C): This advanced variant uses clustering to monitor diversity in each dimension of the search space independently. When a dimension shows signs of stagnation, adaptive mutation strategies (e.g., Gaussian perturbation) are applied specifically to that dimension to reintroduce diversity without disrupting progress in other dimensions [16].

- Adaptive Lévy Flight Mutation: The algorithm can use an adaptive strategy based on the Lévy flight distribution, which combines long-distance jumps (to escape local optima) with local fine-tuning steps. The strategy can switch between global and local mutation based on feedback from the population's convergence state [17].

- Hybridization with Local Searches: Many successful implementations combine the global search of PSO with local refinement steps. After the PSO update, particles can be locally optimized using methods like gradient descent to find the nearest local minimum on the PES, effectively transforming the landscape into a collection of basins [11] [3] [14].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard PSO Workflow for Molecular Cluster Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for optimizing molecular cluster structures using a standard PSO algorithm.

Standard PSO Workflow for Molecular Clusters

Detailed Methodology:

- Problem Definition: The objective is to find the atomic coordinates that minimize the total potential energy of the molecular cluster. The search space is R³ᴺ, where N is the number of atoms [3].

- Swarm Initialization: A swarm of particles is created. Each particle is assigned:

- Fitness Evaluation: The "fitness" of a particle is its potential energy. For molecular systems, this can be calculated using:

- Force Fields/Classical Potentials: A low-cost option like a harmonic (Hookean) potential to model atomic interactions, useful for initial testing and validation [3].

- Quantum Mechanical Methods: More accurate but computationally expensive methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT). These are often used for final validation or in a hybrid workflow where PSO provides candidate structures for subsequent DFT refinement [3] [14].

- Update

pbestandgbest: Each particle's current position is compared to itspbest. If the current energy is lower,pbestis updated. The best position among allpbestvalues is designated asgbest[12]. - Update Velocity and Position: The core PSO equations are applied for each particle i and dimension d:

- Convergence Check: The algorithm repeats from step 3 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations, or no improvement in

gbestfor a set number of steps). - Output: The

gbestposition is returned as the putative global minimum structure [3].

Protocol 2: Hybrid PSO-DFT Validation Protocol

For high-accuracy predictions, a common practice is to use a multi-stage approach.

Hybrid PSO-DFT Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Global Search with PSO: Run the PSO algorithm using a fast, approximate potential energy function (e.g., a harmonic potential or a semi-empirical method) to efficiently generate a set of low-energy candidate structures from across the PES [3].

- Local Optimization: Take the best candidate structures from the PSO search (e.g., the

gbestand other unique low-energypbeststructures) and perform a local geometry optimization using a high-level quantum mechanical method like DFT. This refines the structures to their nearest "true" local minimum on the accurate PES [11] [14]. - Frequency Analysis: Perform a vibrational frequency calculation (a second derivative test) on the locally optimized structures from step 2. This confirms that the structure is a genuine minimum (all frequencies real) and not a saddle point [11].

- Final Ranking and Validation: The structure with the lowest energy after this rigorous local refinement is designated as the global minimum. Its geometric parameters (bond lengths, angles) can be compared against experimental data, such as X-ray diffraction structures, for validation [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for PSO-based Molecular Cluster Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Role in the Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| PSO Algorithm Implementation | Custom code (Fortran 90 [3], Python [14] [12]), Modified variants (ELPSO-C [16], subswarm-PSO [15]). | The core engine that performs the global search for low-energy cluster structures. |

| Potential Energy Function | Harmonic/Hookean potential [3], Density Functional Theory (DFT) software (Gaussian [3] [14], ADFT [11]). | Defines the molecular mechanics and calculates the energy (fitness) for a given cluster geometry. |

| Local Optimization & Analysis | Local optimizers (e.g., in Gaussian), Frequency analysis tools. | Refines PSO candidates to the nearest local minimum and verifies their stability. |

| Structure Comparison & Redundancy Check | Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculators, Point group symmetry detectors. | Identifies and removes duplicate cluster structures from the swarm to maintain diversity. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES)? A Potential Energy Surface (PES) describes the energy of a system, typically a collection of atoms, in terms of certain parameters, which are normally the positions of the atoms [18]. It is a fundamental concept in theoretical chemistry and physics for exploring molecular properties and reaction dynamics [18].

What is the difference between a global minimum and a local minimum on a PES? A global minimum is the point on the PES with the absolute lowest energy, representing the most stable configuration of the system. A local minimum is a point that is lower in energy than all immediately surrounding points but is not the lowest point on the entire surface. A system in a local minimum is metastable [18] [2].

Why is it crucial to locate the global minimum for molecular clusters? Finding the global minimum configuration of a molecular cluster is essential because it corresponds to the structure with the greatest stability [18]. In drug discovery, a molecule's biological activity is often tied to its lowest-energy conformation. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithms are highly effective for navigating the complex PES of molecular clusters to locate this global minimum amidst numerous local minima.

What is a saddle point or transition state? A saddle point, or transition state, is a critical point on the PES that represents the highest energy point along the lowest energy pathway (the reaction coordinate) connecting a reactant to a product [18] [19]. It is a maximum in one direction and a minimum in all other perpendicular directions [19].

My optimization algorithm gets trapped in local minima. How can I improve it? This is a common challenge. You can enhance your Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) protocol by:

- Adjusting Swarm Parameters: Fine-tuning the inertia weight and social/cognitive parameters can balance exploration and exploitation.

- Implementing Hybrid Algorithms: Combining PSO with local search methods can help the algorithm escape local minima.

- Increasing Swarm Diversity: Using a larger swarm size or introducing random re-initialization can help explore a broader area of the PES.

Troubleshooting Common Computational Experiments

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes & Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | Convergence to high-energy structures. | PSO parameters favor exploitation; insufficient swarm diversity. | Increase swarm size; adjust PSO parameters to promote exploration; implement a hybrid algorithm [20]. |

| Reaction Pathway Analysis | Unable to locate a transition state. | Starting geometry is too far from the saddle point; algorithm is not designed for saddle point search. | Use the growing string method; start from a geometry interpolated between reactant and product; employ algorithms specifically designed for saddle point location [18] [2]. |

| Energy Calculations | Inconsistent energies for the same geometry. | The level of theory (e.g., basis set, electronic correlation method) is not consistent across calculations. | Standardize computational method; ensure consistent convergence criteria in all calculations. |

| Handling Large Systems | Calculation is computationally intractable. | The PES dimensionality (3N-6 for N atoms) is too high [19]. | Focus on key degrees of freedom; use coarse-grained models; apply machine learning potentials for faster evaluation [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Locating Minima on a PES using Particle Swarm Optimization This protocol is designed to find the global minimum energy structure of a molecular cluster.

- System Initialization: Define the number of atoms (N) in your molecular cluster. Generate an initial swarm of candidate structures (particles) with random atomic coordinates. The dimensionality of the search space is 3N-6 [19].

- Energy Evaluation: For each particle in the swarm, calculate its potential energy using a pre-defined method (e.g., an empirical force field or a machine learning potential [2]).

- Update Personal & Global Best: For each particle, track its lowest-energy configuration found so far (personal best, pbest). Identify the lowest-energy configuration found by the entire swarm (global best, gbest).

- Particle Position and Velocity Update: Update the velocity and position of each particle based on standard equations that incorporate its previous velocity, its pbest, and the swarm's gbest.

- Iteration and Convergence: Repeat steps 2-4 for a set number of iterations or until the gbest energy converges (shows negligible improvement over multiple cycles).

- Validation: Perform a local geometry optimization on the final gbest structure to ensure it is a true minimum (all vibrational frequencies are real and positive).

Protocol 2: Constructing a One-Dimensional Potential Energy Curve This protocol is used to visualize the energy change along a specific reaction coordinate, such as a bond length.

- Define the Reaction Coordinate: Select a single geometric parameter to vary (e.g., the distance between two atoms, R₁).

- Constrain the Coordinate: Fix the chosen coordinate at a series of values (R₁⁽¹⁾, R₁⁽²⁾, ..., R₁⁽ⁿ⁾) while optimizing all other geometric degrees of freedom.

- Calculate Single-Point Energies: For each value of the constrained coordinate, perform a single-point energy calculation on the partially optimized structure.

- Plot the PES: Plot the calculated energy (E) against the reaction coordinate (R₁) to create a one-dimensional potential energy curve [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface | The foundational theoretical construct that maps the energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates; essential for understanding structure, stability, and reactivity [18]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | A computational algorithm used to search high-dimensional PESs for the global minimum energy structure by simulating the social behavior of a swarm of particles [20]. |

| Born-Oppenheimer Approximation | A key approximation that allows for the separation of electronic and nuclear motion, making the calculation of a PES feasible [19]. |

| Transition State Theory | A framework for calculating the rates of chemical reactions that relies on the properties of the saddle point on the PES [18]. |

| Anharmonic Force Field | A mathematical representation (Taylor series) of the PES near a minimum, which includes terms beyond the quadratic to accurately model large-amplitude vibrations [2]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials | A class of methods that use machine learning (e.g., kernel methods, neural networks) to create accurate and computationally efficient representations of PESs from quantum mechanical data [2]. |

Quantitative Data for a Model System: H + H₂

The H + H₂ reaction (Hₐ + Hᵦ–H꜀ → Hₐ–Hᵦ + H꜀) is a classic model system for studying PES concepts [18] [19].

Table 1: Key Features on the H+H₂ Potential Energy Surface

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Energy Relative to Reactants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant Minimum | R | H + H₂ (separated) | ~ 0 kcal/mol |

| Product Minimum | P | H₂ + H (separated) | ~ 0 kcal/mol |

| Saddle Point | TS | H -- H -- H transition state [19] | ~ 9.7 kcal/mol [19] |

Table 2: Key Geometric Parameters at the Stationary Points for H+H₂

| Structure | Hₐ–Hᵦ Distance (Å) | Hᵦ–H꜀ Distance (Å) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant (H + H₂) | ∞ | ~0.74 | Isolated H atom and H₂ molecule at equilibrium bond length. |

| Transition State | ~0.93 | ~0.93 | Symmetric, stretched H-H bonds [19]. |

| Product (H₂ + H) | ~0.74 | ∞ | H₂ molecule at equilibrium bond length and isolated H atom. |

Conceptual Diagrams

The Role of Stochastic vs. Deterministic Global Optimization Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between stochastic and deterministic global optimization methods?

A1: Deterministic methods provide a theoretical guarantee of finding the global optimum by exploiting specific problem structures, and they will yield the same result every time when run with the same initial conditions [21]. In contrast, stochastic methods incorporate random processes, which means they do not guarantee the global optimum but often find a good, acceptable solution in a feasible time frame; the probability of finding the global optimum increases with longer runtimes [21] [11].

Q2: Why would I choose a stochastic method like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for my molecular cluster research?

A2: For molecular cluster research, the Potential Energy Surface (PES) is typically high-dimensional and exhibits a rapidly growing number of local minima as system size increases [11]. Stochastic methods like PSO are particularly well-suited for exploring such complex, multimodal landscapes because they can sample the search space broadly and avoid premature convergence to local minima [11]. Their population-based nature allows for a more effective global search compared to many deterministic sequential methods.

Q3: My stochastic optimization is converging too quickly to a sub-optimal solution. How can I improve its exploration?

A3: Premature convergence is a common challenge. You can address it by:

- Hybrid Strategies: Integrate a local search method (like the Hook-Jeeves strategy) to refine solutions and improve local search accuracy [22].

- Mutation Mechanisms: Introduce a Cauchy or Lévy flight mutation mechanism to diversify the swarm and help it escape local optima [17] [22].

- Parameter Tuning: Adjust the inertia weight (

w) to a higher value to promote global exploration over local exploitation, and fine-tune the cognitive (c1) and social (c2) coefficients [7].

Q4: In what scenarios would a deterministic method be more appropriate?

A4: Deterministic methods are more appropriate when the problem scale is manageable and the global optimum must be found with certainty. They are often applied to problems with clear, exploitable features, such as those that can be formulated as Linear Programming (LP) or Nonlinear Programming (NLP) models [21]. They are also highly valuable for lower-dimensional problems or those with specific structures where exhaustive or rigorous algorithms can be practically applied [23].

Q5: How do I balance exploration and exploitation in the PSO algorithm?

A5: Balancing exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas) is achieved through key parameters [7]:

- Inertia Weight (

w): A higherwencourages exploration, while a lowerwfavors exploitation. Using an adaptive weight that decreases over the run can transition the swarm from global exploration to local refinement. - Cognitive (

c1) and Social (c2) Coefficients: A higherc1directs particles toward their personal best, maintaining diversity. A higherc2pulls particles toward the global best, accelerating convergence. Adaptive strategies that adjust these coefficients based on the swarm's state can further enhance performance [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: The algorithm fails to find the known global minimum for a molecular cluster.

- Possible Cause 1: Poor parameter settings.

- Solution: Perform a parameter sensitivity analysis. Systematically vary parameters like swarm size, inertia weight, and coefficients across multiple runs to find a robust configuration for your specific problem.

- Possible Cause 2: Insufficient computational budget.

- Solution: Increase the maximum number of iterations or function evaluations. Stochastic methods require adequate time to explore the complex energy landscape of molecular clusters [11].

- Possible Cause 3: The problem is highly multimodal, and the swarm is getting trapped.

Problem 2: The optimization process is computationally too slow.

- Possible Cause 1: The fitness evaluation (e.g., energy calculation) is expensive.

- Solution: Use surrogate models or machine learning to approximate the fitness function for less promising candidates, reserving full, expensive evaluations only for elite particles [11].

- Possible Cause 2: The swarm size is too large.

- Solution: Reduce the swarm size. A common guideline is to start with 20-40 particles [7], but the optimal size is problem-dependent.

- Possible Cause 3: The algorithm is not exploiting convergence.

Problem 3: The results are inconsistent between runs.

- Possible Cause: Inherent randomness in stochastic algorithms.

- Solution: This is an inherent property of stochastic methods. To obtain a reliable result, perform multiple independent runs and report the best solution found or the average performance. Statistical analysis of the results is essential [23].

Performance Comparison Table

The table below summarizes a benchmark study comparing deterministic and stochastic derivative-free optimization algorithms across problems of varying dimensions [23].

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Global Optimizers

| Problem Dimension | Algorithm Category | Relative Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Dimensional | Deterministic | Excellent | Excels on simpler and low-dimensional problems. |

| Low-Dimensional | Stochastic | Good | Performs well but may be outperformed by deterministic methods. |

| Higher-Dimensional | Deterministic | Struggles | Computational cost may become prohibitive. |

| Higher-Dimensional | Stochastic | More Efficient | Better suited for navigating complex, high-dimensional search spaces. |

Workflow & Method Selection Diagram

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for selecting and applying global optimization methods in molecular cluster research, incorporating hybrid strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key "reagents" – in this context, algorithmic components and software strategies – essential for successfully optimizing molecular cluster structures.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Cluster Optimization

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Search Operator | Explores the search space broadly to locate promising regions and avoid local minima. | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [24] [11]. |

| Local Refinement Operator | Exploits and refines a promising solution to achieve high accuracy once a good region is found. | Hook-Jeeves pattern search [22] or gradient-based methods. |

| Mutation Strategy | Introduces diversity into the population/swarm to prevent premature convergence. | Cauchy mutation [22] or adaptive Lévy flight [17]. |

| Hybrid Framework | Integrates global and local search for a balanced and efficient optimization process. | PSO combined with a local pattern search method [25] [22]. |

| Fitness Evaluator | Computes the quality of a candidate solution (e.g., its energy on the PES). | First-principles Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [11]. |

Implementing PSO for Molecular Structure Prediction and Drug Design

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based stochastic optimization metaheuristic inspired by the social behavior observed in bird flocking and fish schooling [26]. In computer science, PSO is recognized as a high-quality algorithm that utilizes social behavior and intelligence to find solutions in complex search spaces, where candidate solutions, referred to as particles, evaluate their performance and influence each other based on their successes [26]. For molecular systems research, particularly in predicting stable molecular cluster configurations, PSO has emerged as a valuable tool for global optimization of molecular structures, overcoming limitations of traditional methods that often become trapped in local minima [3] [14].

The fundamental PSO algorithm operates by having a swarm of particles, each representing a potential solution, that move through a multidimensional search space. Each particle adjusts its position based on its own experience (personal best - pbest) and the best experience of the entire swarm (global best - gbest) [26]. The velocity and position update equations are:

where w is the inertia weight, c_1 and c_2 are acceleration coefficients, and r_1 and r_2 are random numbers between 0 and 1 [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Particle Representation

Q: How should particles be represented when optimizing molecular cluster structures?

Particles should be represented as the atomic coordinates of the entire molecular cluster in a 3N-dimensional space, where N is the number of atoms in the system [3]. For a cluster of N atoms, each particle's position is represented as a vector in R^3N space, containing the (x, y, z) coordinates for all atoms [3]. This representation allows the PSO algorithm to explore different spatial configurations of the molecular cluster by updating these coordinates iteratively.

Q: What are the key considerations for particle initialization in molecular PSO?

Initial particle positions should be generated randomly within reasonable spatial boundaries to ensure diverse starting configurations [14]. Research on carbon clusters (C_n, n = 3-6, 10) has demonstrated that PSO can successfully transform arbitrary and randomly generated initial structures into global minimum energy configurations [14]. The population size should be sufficient to adequately explore the complex potential energy surface, with studies successfully using relatively small population sizes for carbon clusters [14].

Fitness Functions

Q: What fitness functions are most appropriate for molecular cluster optimization?

The most fundamental fitness function is the potential energy of the molecular system [3] [14]. For efficient preliminary optimization, a simple harmonic potential based on Hooke's Law can be used as it has lower computational cost [3]. For higher accuracy, density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide more reliable energy evaluations but at greater computational expense [3] [14]. The harmonic potential function treats atoms as rigid spheres connected by springs, with the restoring force proportional to displacement from equilibrium length [3].

Q: How do I choose between different fitness function implementations?

The choice depends on your research goals and computational resources. For rapid screening of configuration space or large systems, harmonic potentials offer practical efficiency [3]. For final accurate energy determinations, especially for publication-quality results, DFT calculations are necessary [14]. Many researchers employ a hybrid approach: using PSO with harmonic potentials for initial global search, followed by DFT refinement of promising candidates [3].

Algorithm Implementation

Q: What PSO topology works best for molecular cluster optimization?

The gbest neighborhood topology has been successfully implemented for molecular clustering problems [27] [3]. In this approach, each particle remembers its best previous position and the best previous position visited by any particle in the entire swarm [27]. Each particle moves toward both its personal best position and the best particle in the swarm, facilitating efficient exploration of the complex potential energy surface [27].

Q: How should PSO parameters be tuned for molecular applications?

Parameter tuning is crucial for PSO performance [26]. The inertia weight (w) controls the influence of previous velocity, while acceleration coefficients (c_1, c_2) balance the cognitive and social components [26]. For molecular cluster optimization, adaptive parameter strategies often work well, where these values may be set to constant values or varied over time to improve convergence and avoid premature convergence [26]. Velocity clamping is typically used to prevent particles from leaving the reasonable search space [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Convergence Problems

Problem: Premature convergence to local minima

Solution: Implement diversity preservation mechanisms such as:

- Turbulent PSO operators that introduce minimum velocity and random turbulence to prevent stagnation [26]

- Adaptive inertia weight that changes with population evolution [26]

- Multi-swarm approaches that maintain subpopulations exploring different regions [26]

Problem: Slow convergence rate

Solution:

- Implement hybrid approaches that combine PSO with local search methods [27] [14]

- Use fitness approximation techniques for computationally expensive DFT calculations [3]

- Apply parallel computing implementations to evaluate multiple particles simultaneously [28]

Representation and Boundary Issues

Problem: Unphysical molecular geometries

Solution:

- Implement constraint handling mechanisms to maintain reasonable bond lengths and angles [14]

- Use boundary conditions that reflect particles back into valid search regions [26]

- Incorporate chemical knowledge through penalty functions in the fitness evaluation [14]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Workflow for Molecular Cluster Optimization

Workflow for Molecular Cluster Optimization

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of PSO Fitness Functions for Molecular Cluster Optimization

| Fitness Function | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Potential [3] | Low | Moderate | Initial structure screening, Large clusters | Limited chemical accuracy |

| Density Functional Theory [3] [14] | High | High | Final structure determination, Publication results | Computationally expensive |

| Hybrid Approaches [3] | Medium | High-Medium | Most practical applications | Implementation complexity |

Table 2: PSO Parameters for Molecular Cluster Optimization

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Effect | Adjustment Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inertia Weight (w) [26] | 0.4-0.9 | Controls exploration vs exploitation | Decrease linearly during optimization |

| Cognitive Coefficient (c₁) [26] | 1.5-2.0 | Attraction to personal best | Keep constant or slightly decrease |

| Social Coefficient (c₂) [26] | 1.5-2.0 | Attraction to global best | Keep constant or slightly increase |

| Population Size [14] | 20-50 particles | Exploration diversity | Increase with system complexity |

| Velocity Clamping [26] | System-dependent | Prevents explosion | Set to 10-20% of search space |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular PSO Research

| Tool Category | Specific Implementations | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO Algorithms | Fortran 90 implementation [3] | Global optimization of cluster structures | Custom PSO development |

| Python PSO modules [29] | Flexible algorithm implementation | Rapid prototyping | |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian 09 [3] [14] | Accurate energy calculations via DFT | High-accuracy fitness evaluation |

| Structure Analysis | Basin-Hopping (BH) method [3] | Comparative optimization method | Algorithm validation |

| Parallel Computing | Apache Spark [28] | Distributed fitness evaluation | Large-scale cluster optimization |

Advanced Implementation Strategies

Multiobjective Optimization for Molecular Systems

For complex molecular systems, single-objective optimization may be insufficient. Multiobjective PSO (MOPSO) approaches can simultaneously optimize multiple criteria, such as:

- Overall clustering deviation metric: Calculates the total distance between data object instances to their corresponding clustering centers [28]

- Clustering connectivity metric: Measures how often neighboring objects are assigned to the same cluster [28]

The multiobjective clustering problem can be formalized as:

where f_i:Ω→R is the ith different optimization criterion [28].

Parallel Computing Implementations

Parallel PSO Implementation Architecture

Distributed computing frameworks like Apache Spark can significantly accelerate PSO for molecular systems by:

- Partitioning data across multiple compute nodes [28]

- Performing parallel fitness function evaluations [28]

- Reducing algorithm runtime through in-memory operations [28]

- Implementing weighted average calculations to handle unbalanced data distribution [28]

This approach is particularly valuable when using computationally expensive fitness functions like DFT calculations, where parallelization can reduce wall-clock time significantly.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using HSAPSO over standard PSO for training Stacked Autoencoders (SAE) in drug discovery?

The primary advantage is the superior adaptability and convergence behavior. The hierarchically self-adaptive mechanism in HSAPSO dynamically fine-tunes hyperparameters during training, optimally balancing global exploration and local exploitation of the solution space. This leads to higher classification accuracy (reported up to 95.52% for drug-target identification), significantly reduced computational complexity (0.010 seconds per sample), and exceptional stability (± 0.003) compared to traditional optimization methods, which often result in suboptimal performance and overfitting on complex pharmaceutical datasets [30].

2. My model is converging prematurely to a local optimum. How can HSAPSO help mitigate this?

Premature convergence is often a sign of poor exploration. HSAPSO addresses this through its hierarchical structure. It employs strategies like dynamic leader selection and adaptive control parameters. If particles start clustering around a suboptimal solution, the self-adaptive component adjusts the inertia and acceleration coefficients, encouraging the swarm to escape local minima and continue exploring the search space more effectively [30]. Integrating mechanisms like Levy flight perturbations can further help by introducing long-distance jumps to explore new regions [31].

3. During data preprocessing, my high-dimensional molecular features lead to a dimensional mismatch with the SAE input. What is the standard procedure to handle this?

Dimensional mismatch is a common challenge. The standard procedure involves a feature dimensionality standardization step [32]. This typically involves:

- Applying dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or an initial autoencoder layer to project features into a lower-dimensional, dense representation.

- Ensuring standardized and compatible feature representations across all input data types. The goal is to transform raw, heterogeneous features (e.g., molecular descriptors, protein sequences) into a uniform dimensional space before they are fed into the main SAE for further hierarchical feature extraction [32].

4. The performance of my HSAPSO-SAE model is highly sensitive to the initial parameter settings. Is there a recommended method for parameter meta-optimization?

Yes, parameter meta-optimization is crucial. A proven method is the "superswarm" approach, also known as Optimized PSO (OPSO) [33]. This method uses a superordinate swarm to optimize the parameters (e.g., inertia weights, acceleration coefficients) of subordinate swarms. Each subswarm runs a complete HSAPSO-SAE optimization, and its average performance is fed back to the superswarm. This process identifies a robust set of parameters that provide consistently good performance across multiple runs, reducing sensitivity to initial conditions [33].

5. How can I validate that the features extracted by the SAE are meaningful for molecular cluster research and not just artifacts of the training data?

Validation requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Quantitative Performance: The most direct validation is the model's performance on downstream tasks like drug-target interaction prediction or molecular potency classification, using metrics like AUC-ROC [30].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the extracted features against known molecular descriptors or features used in established methods (e.g., SVM, XGBoost). Superior performance suggests the SAE is capturing more informative, latent representations [30].

- Robustness Checks: Evaluate the model's stability and performance on unseen data or different molecular datasets to ensure the features generalize well and are not overfitted [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Convergence and High Training Error

Problem: The HSAPSO-SAE model fails to converge, or the training error remains high and erratic across epochs.

Solutions:

- Check Data Preprocessing:

- Ensure all input data (e.g., molecular structures, protein sequences) have been properly normalized and standardized. Categorical variables should be one-hot encoded [34].

- Verify there are no missing values in your datasets. Impute any missing values using appropriate methods, such as the mean for numerical features [34].

- Adjust HSAPSO Parameters:

- Implement Adaptive Inertia Weights: Use a time-varying inertia weight that decreases linearly from around

0.9to0.4over iterations. This shifts the focus from exploration to exploitation gradually [31]. - Tune Acceleration Coefficients: The cognitive (

c1) and social (c2) parameters guide particle movement. Start with standard values (e.g.,c1 = c2 = 2.0) and use the meta-optimization ("superswarm") technique to find the optimal values for your specific problem [33].

- Implement Adaptive Inertia Weights: Use a time-varying inertia weight that decreases linearly from around

- Inspect SAE Architecture:

- The SAE might be too deep or too shallow for the problem's complexity. Experiment with the number of layers and neurons per layer.

- Ensure that the SAE is correctly pre-trained in an unsupervised, layer-wise manner before fine-tuning with HSAPSO.

Issue 2: Model Overfitting on Training Data

Problem: The model performs exceptionally well on the training data but poorly on the validation or test set.

Solutions:

- Introduce Regularization:

- Apply L1 or L2 regularization to the weights of the SAE to penalize overly complex models.

- Use Dropout during training to randomly disable a fraction of neurons, forcing the network to learn more robust features.

- Enhance HSAPSO's Exploration:

- Incorporate opposition-based learning during the initialization of the particle swarm. This generates a more diverse initial population, improving the coverage of the search space and helping to avoid overfitting to spurious patterns [31].

- Utilize Levy flight perturbations within the HSAPSO update process. This introduces occasional large jumps, helping the algorithm escape local optima that correspond to overfitted solutions [31].

- Employ Early Stopping:

- Monitor the error on a validation set during training. Halt the HSAPSO optimization process when the validation error begins to increase consistently, even if the training error continues to decrease.

Issue 3: High Computational Cost and Slow Training Time

Problem: The training process for the HSAPSO-SAE framework is prohibitively slow, especially with large-scale biological datasets.

Solutions:

- Optimize Feature Dimensionality:

- Leverage Parallel Computing:

- The evaluation of particles in the HSAPSO swarm is inherently parallelizable. Distribute the fitness evaluation (which involves running the SAE) across multiple CPU/GPU cores to significantly reduce wall-clock time [30].

- Use a Modular Design:

- Adopt a framework like PSO-FeatureFusion, which models different feature pairs with lightweight neural networks. This modular design allows for parallel training and is computationally more efficient than end-to-end training of a massive monolithic network [32].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Methodology: optSAE + HSAPSO for Drug Classification

The following workflow is adapted from state-of-the-art research on automated drug design [30].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Datasets: Utilize curated pharmaceutical datasets from sources like DrugBank and Swiss-Prot.

- Preprocessing Steps:

Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) for Feature Extraction:

- Architecture: Construct a deep network of multiple autoencoder layers.

- Pre-training: Train each autoencoder layer independently in an unsupervised manner to learn a compressed representation of its input.

- Stacking: Stack the trained encoder layers to form the SAE, which serves as a robust feature extractor.

Hierarchically Self-Adaptive PSO (HSAPSO) for Optimization:

- Initialization: Initialize a swarm of particles where each particle's position represents a potential set of hyperparameters for the SAE (e.g., learning rates, regularization parameters).

- Hierarchical Adaptation: Implement a strategy where parameters like inertia weight (

w) and acceleration coefficients (c1,c2) adapt dynamically based on the swarm's performance and each particle's state [30] [31]. - Fitness Evaluation: For each particle's hyperparameter set, fine-tune the pre-trained SAE and evaluate its classification accuracy on a validation set. This accuracy is the particle's fitness.

- Swarm Update: Update particle velocities and positions based on individual best (

pbest) and global best (gbest) positions, using the adaptively tuned parameters.

Final Model Evaluation:

- Once HSAPSO converges, take the best-performing hyperparameter set (

gbest). - Train the final SAE model with these optimized parameters on the full training set.

- Evaluate the model's performance on a held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC-ROC.

- Once HSAPSO converges, take the best-performing hyperparameter set (

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Drug Classification Models [30]

| Model / Framework | Accuracy (%) | Computational Complexity (s/sample) | Stability (±) |

|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE + HSAPSO (Proposed) | 95.52 | 0.010 | 0.003 |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | < 89.98 | Higher | Lower |

| XGBoost-based Models | ~94.86 | Higher | Lower |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| DrugBank / Swiss-Prot Datasets | Provides curated, high-quality data on drugs, targets, and protein sequences for model training and validation. | Public Databases [30] |

| NSL-KDD / CICIDS Datasets | Benchmark datasets used for evaluating model robustness and generalizability, even in non-bioinformatics domains like network security [34]. | Public Repositories [34] |

| Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) | A deep learning architecture used for unsupervised hierarchical feature extraction from high-dimensional input data. | Custom Implementation (e.g., in Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch) [30] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A population-based stochastic optimization algorithm that simulates social behavior to find optimal solutions. | Standard Library or Custom Code [30] [14] |

| Cosine Similarity & N-Grams | Feature extraction techniques used to assess semantic proximity and relevance in drug description text data [35]. | NLP Libraries (e.g., NLTK, scikit-learn) |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Diagram 1: HSAPSO-SAE High-Level Workflow

Diagram 2: Hierarchically Self-Adaptive PSO (HSAPSO) Structure

Technical Specifications and Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of the optSAE+HSAPSO framework as established in experimental evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the optSAE+HSAPSO Framework

| Metric | Reported Value | Context & Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Classification Accuracy | 95.52% [36] | Outperforms traditional methods like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and XGBoost, which often struggle with large, complex pharmaceutical datasets [36]. |

| Computational Speed | 0.010 seconds per sample [36] | Significantly reduced computational overhead, enabling faster analysis of large-scale datasets [36]. |

| Stability | ± 0.003 [36] | Exceptional stability across validation and unseen datasets, indicating consistent and reliable performance [36]. |

| Key Innovation | Hierarchically Self-Adaptive PSO (HSAPSO) for SAE tuning [36] | First application of HSAPSO to optimize Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) hyperparameters in drug discovery, dynamically balancing exploration and exploitation during training [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My model is converging too quickly and seems to be stuck in a suboptimal solution. How can I improve the exploration of the search space?

Answer: This is a classic sign of the optimization process getting trapped in a local minimum. The HSAPSO component is specifically designed to address this.

- Check HSAPSO Parameters: The "hierarchically self-adaptive" nature of the PSO algorithm means that parameters like inertia weight and acceleration coefficients can adjust during the optimization process. Ensure that the initial settings for these parameters allow for sufficient global exploration in the early stages [36].

- Verify Particle Swarm Size: A swarm that is too small may not adequately cover the complex hyperparameter search space. Consider increasing the number of particles to improve the diversity of searched solutions, which is a common strategy in PSO to enhance global search capability [37].

- Review Solution Diversity: Implement mechanisms to monitor the diversity of the particle swarm throughout the optimization run. A loss of diversity often precedes premature convergence. Some PSO variants incorporate mutation strategies to reintroduce diversity and help the swarm escape local optima [37].

FAQ 2: The training process is computationally expensive and slow with my high-dimensional dataset. What optimizations can I make?

Answer: While the optSAE+HSAPSO framework is designed for efficiency, high-dimensional data can still pose challenges.

- Leverage Feature Extraction: The Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) is a core part of the framework designed for robust feature extraction. Ensure that the SAE is properly configured to learn efficient, lower-dimensional representations of your input data before the classification step. This compresses the information and reduces the computational burden downstream [36].

- Data Quality Preprocessing: The framework's performance is dependent on the quality of the training data. Invest time in rigorous data preprocessing, including normalization and handling of missing values, to improve the efficiency of the learning process [36].

- Hardware Acceleration: Utilize hardware accelerators like GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) which are highly effective for the matrix and vector operations fundamental to both deep learning (SAE) and swarm intelligence (HSAPSO) computations.

FAQ 3: How can I validate that the identified drug targets are reliable and not false positives?

Answer: Model interpretation and validation are critical in biomedical applications.

- Robustness Metrics: Rely on the framework's demonstrated stability (± 0.003) and high AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) values. A high AUC-ROC, confirmed to be 0.93 or higher in similar biomedical classification tasks, indicates a strong ability to distinguish between true and false positives [36] [38].

- Independent Experimental Validation: Computational predictions must be confirmed with wet-lab experiments. Techniques like Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) can be used to validate interactions biochemically. DARTS monitors changes in protein stability upon drug binding, helping to confirm potential target proteins identified by your model [39].

- Cross-Dataset Validation: Test your trained model on a completely unseen dataset from a different source (e.g., a different database or experimental batch) to confirm that its performance generalizes and is not overfitted to your initial training data [36].

Experimental Protocol: Core Workflow for Drug Target Identification

This section outlines the standard methodology for employing the optSAE+HSAPSO framework.

Step 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Action: Gather drug-related data from curated sources such as DrugBank and Swiss-Prot, as used in the foundational study [36].

- Details: This involves collecting features related to proteins and compounds. Perform rigorous preprocessing including handling missing values, data normalization, and feature scaling to ensure optimal input quality for the model [36].

Step 2: Feature Extraction with Stacked Autoencoder (SAE)

- Action: Train a Stacked Autoencoder to learn hierarchical and compressed representations of the input data.

- Details: The SAE consists of multiple layers of encoder and decoder networks. The encoder layers progressively reduce the dimensionality of the input, learning the most salient features. The decoder attempts to reconstruct the input from this compressed representation. The output of the innermost encoding layer is used as the extracted feature set for classification [36].

Step 3: Hyperparameter Optimization with HSAPSO

- Action: Use the Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm to find the optimal hyperparameters for the SAE.

- Details:

- Initialize a population (swarm) of particles, where each particle's position represents a candidate set of SAE hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, nodes per layer).

- Evaluate each particle's position by training the SAE with its hyperparameters and assessing the performance (e.g., reconstruction error).

- Update each particle's velocity and position based on:

- Repeat the evaluation and update steps until a stopping criterion (e.g., maximum iterations or performance threshold) is met.

Step 4: Model Training and Classification

- Action: Train the final optSAE model (with HSAPSO-optimized parameters) for the classification task (e.g., druggable vs. non-druggable target).

- Details: Use the optimized SAE for feature extraction and add a final classification layer (e.g., a softmax layer). Train the entire network end-to-end on your labeled dataset for drug target identification [36].

Framework Architecture and Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated architecture of the optSAE+HSAPSO framework and the flow of data and optimization signals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and data resources essential for implementing the optSAE+HSAPSO framework.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specific Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Biomedical Databases | Provides structured, high-quality data for training and validating the model on known drug-target interactions and protein features. | DrugBank, Swiss-Prot [36]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Library | Provides the core algorithms for the hierarchically self-adaptive optimization of the SAE's hyperparameters. | Custom implementation (e.g., in Fortran, Python) [3]. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Provides the environment for building, training, and evaluating the Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) and classification layers. | TensorFlow, PyTorch. |

| Validation Assay | Used for experimental confirmation of computationally predicted drug targets in a biochemical context. | Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our STELLA simulation consistently converges to sub-optimal molecular structures. How can we improve the global search capability?

You are likely experiencing premature convergence, where the algorithm gets trapped in a local minimum. This is a common challenge in multi-parameter optimization. To address it:

- Adjust the PSO Hyper-parameters: The performance of Particle Swarm Optimization is highly dependent on its parameters [40]. Experiment with increasing the swarm size (number of particles) to explore a broader region of the chemical space. Additionally, adjusting the acceleration coefficients can help balance the influence of a particle's own experience (cognitive component) and the swarm's collective knowledge (social component) [40].

- Implement a Hybrid Approach: Combine PSO with a local search method like linear gradient descent. This allows the algorithm to perform a wide-ranging global search with PSO first, and then refine the best solutions with a efficient local search, ensuring you identify a solution that is both globally robust and locally optimal [40].

- Verify Your Fitness Function: Ensure your objective function, which may combine docking scores, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), and other pharmacological properties, correctly represents the multi-faceted goals of your drug design project [41].

Q2: What is the recommended workflow for integrating PSO-based generative design with experimental validation?

A robust, cyclical workflow ensures computational predictions are grounded in experimental reality. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Q3: How does STELLA's performance compare to other generative models like REINVENT 4?

STELLA demonstrates specific advantages in scaffold diversity and hit generation. A comparative case study focusing on identifying phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) inhibitors showed the following results [41]:

| Metric | STELLA | REINVENT 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Hit Compounds | 368 | 116 |

| Hit Rate | 5.75% per iteration | 1.81% per epoch |

| Unique Scaffolds | 161% more | Baseline |

| Mean Docking Score (GOLD PLP Fitness) | 76.80 | 73.37 |

| Mean QED | 0.75 | 0.75 |

Q4: We are observing a lack of chemical diversity in our generated molecules. How can we enhance exploration?

This issue arises when the algorithm over-exploits a narrow region of chemical space. STELLA incorporates specific mechanisms to combat this [41]: