Navigating Chemical Space: A 2025 Guide to Small Molecule Libraries for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of small molecule libraries and their pivotal role in navigating the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) for modern drug discovery.

Navigating Chemical Space: A 2025 Guide to Small Molecule Libraries for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving landscape of small molecule libraries and their pivotal role in navigating the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) for modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, explores cutting-edge methodological advances like barcode-free screening and DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs), and addresses key challenges in library design and optimization. It further offers a comparative analysis of screening platforms and validation strategies, synthesizing how these integrated approaches are accelerating the identification of novel therapeutics against increasingly complex disease targets.

Mapping the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS): Concepts and Landscapes

The concept of "chemical space" (CS), also referred to as the "chemical universe," represents the multidimensional totality of all possible chemical compounds. In drug discovery and related fields, this abstract concept is made practical through the definition of chemical subspaces (ChemSpas)—specific regions distinguished by shared structural or functional characteristics [1]. A critically important subspace is the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS), which encompasses the vast set of molecules exhibiting biological activity, including those with both beneficial (therapeutic) and detrimental (toxic) effects [1].

Understanding and navigating the BioReCS is fundamental to modern drug discovery. It provides a conceptual framework for organizing chemical information, prioritizing compounds for synthesis and testing, and ultimately designing novel therapeutic agents with desired biological properties. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of chemical space and BioReCS, detailing the computational and experimental methodologies employed for its exploration, with a specific focus on its application to small molecule library research.

Mapping the Theoretical Universe: Dimensions and Descriptors of Chemical Space

The Multidimensional Nature of Chemical Space

Chemical space is intrinsically multidimensional. Each molecular property or structural feature can be considered a separate dimension, with each compound occupying a specific coordinate based on its unique combination of these attributes [1]. The "size" of chemical space is astronomically large, with estimates for drug-like molecules exceeding 10^60, vastly exceeding the capacity of any physical or virtual screening effort [2].

Table 1: Key Dimensions for Characterizing Chemical Space

| Dimension Category | Specific Descriptors & Metrics | Role in Defining Chemical Space |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Descriptors | Molecular Quantum Numbers [1], MAP4 Fingerprint [1], Molecular Fragments/Scaffolds | Define core molecular architecture and topology, enabling scaffold-based clustering and diversity analysis. |

| Physicochemical Properties | Molecular Weight, lipophilicity (cLogP), Polar Surface Area, Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors [3] | Determine "drug-likeness" (e.g., via Lipinski's Rule of 5) and influence pharmacokinetics (ADMET) [3]. |

| Topological & Shape-Based | Morgan Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) [2], Feature Trees [4], 3D Pharmacophore Features | Capture molecular shape and functional group arrangement, crucial for recognizing scaffold hops and predicting target binding. |

| Biological Activity | Target-binding Affinity, On/Off-target Activity Profiles, Toxicity Signatures | Annotates the BioReCS, linking chemical structures to biological function and enabling polypharmacology prediction. |

Navigating the Subspaces: Heavily Explored and Underexplored Regions

The BioReCS is not uniformly mapped. Certain regions have been extensively characterized, while others remain frontiers.

- Heavily Explored ChemSpas: The space of small organic, drug-like molecules is well-studied, largely due to extensive data in public databases like ChEMBL and PubChem [1]. These resources are rich sources of information on poly-active and promiscuous compounds. Closely related spaces, such as those of small peptides and other "beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5)" molecules, are also increasingly well-characterized [1].

- Underexplored ChemSpas: Significant regions of BioReCS remain under-investigated due to modeling challenges. These include:

- Metal-containing molecules and metallodrugs, often filtered out by tools designed for organic compounds [1].

- Complex natural products, macrocycles, and Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) modulators, which often fall into the bRo5 category [1].

- Dark Chemical Matter, comprising compounds consistently inactive in high-throughput screens, and regions of undesirable bioactivity (e.g., toxicity) [1].

Exploring the BioReCS: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The systematic exploration of BioReCS relies on an integrated workflow of computational screening and experimental validation.

Computational Navigation of Ultralarge Libraries

The scale of make-on-demand chemical libraries, which now contain over 70 billion compounds, necessitates highly efficient virtual screening protocols [2]. A state-of-the-art methodology combines machine learning (ML) with molecular docking to rapidly traverse these vast spaces.

Experimental Protocol: Machine Learning-Guided Docking Screen

This protocol is designed for the virtual screening of multi-billion-compound libraries [2].

- Library Preparation: A subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) is randomly selected from an ultralarge library (e.g., Enamine REAL Space). Compounds are often pre-filtered by rules like the "rule-of-four" (molecular weight <400 Da and cLogP < 4) and prepared for docking with tools like RDKit [2].

- Benchmark Docking: The prepared subset is docked against the target protein using a high-performance docking program. The docking scores for all compounds are recorded.

- Classifier Training: A machine learning classifier (e.g., CatBoost is recommended for its optimal speed/accuracy balance) is trained on the benchmark set. The input features are molecular descriptors (e.g., Morgan2 fingerprints), and the learning task is to classify compounds as "virtual active" (top 1% of scores) or "virtual inactive" based on their docking score [2].

- Conformal Prediction for Selection: The trained ML model is applied to the entire multi-billion-member library within a conformal prediction (CP) framework. The CP framework uses a selected significance level (ε) to identify a "virtual active" set from the large library, guaranteeing that the error rate of the predictions will not exceed ε [2].

- Focused Docking: Only the compounds in the much smaller ML-predicted "virtual active" set (often 10-20 million compounds) are subjected to explicit molecular docking. This step reduces the computational cost by more than 1,000-fold while retaining ~90% of the true top-scoring compounds [2].

- Hit Identification & Experimental Validation: The top-ranking compounds from the focused docking are selected for experimental synthesis and testing (e.g., binding or functional assays) to confirm biological activity [2].

Comparative Analysis of Large Chemical Spaces

Assessing the overlap and complementarity of vast chemical spaces is a non-trivial task, as full enumeration is impossible. A novel methodology uses a panel of query compounds to probe different spaces [4].

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Space Comparison via Query Probes

- Query Selection: A panel of 100 reference molecules (e.g., randomly selected, filtered marketed drugs) is assembled to represent a pharmaceutically relevant region of chemical space [4].

- Nearest-Neighbor Search: For each query molecule, the 10,000 most similar compounds are retrieved from each chemical space under investigation (e.g., corporate BICLAIM space, public KnowledgeSpace, commercial REAL Space). This is performed using a fuzzy, scaffold-hopping-capable similarity search method like Feature Trees (FTrees) [4].

- Overlap Analysis: The structural overlap of the resulting hit sets (e.g., ~1 million unique compounds per space) is analyzed. Studies reveal remarkably low overlap, with very few compounds found in all three spaces, indicating high complementarity [4].

- Characterization: The hit sets are further characterized for chemical feasibility using scores like the Synthetic Accessibility score (SAscore) and

rsynth, and their coverage of chemical space is assessed [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BioReCS Exploration

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [1] | Public Database | Repository of bioactive, drug-like small molecules with curated bioactivity data. | Essential for defining regions of BioReCS related to known target pharmacology. |

| PubChem [1] | Public Database | Comprehensive database of chemical substances and their biological activities. | Provides a broad view of assayed chemical space, including negative data. |

| Enamine REAL [2] [4] | Make-on-Demand Library | Ultra-large virtual library of synthetically accessible compounds for virtual screening. | Contains billions of molecules with high predicted synthetic success rates (>80%). |

| FTrees-FS [4] | Software (Search) | Similarity search in fragment spaces without full enumeration, enabling scaffold hops. | Uses Feature Tree descriptor to find structurally diverse, functionally similar compounds. |

| SIRIUS/CSI:FingerID [5] | Software (Annotation) | Predicts molecular fingerprints and compound classes from untargeted MS/MS data. | Maps the "chemical dark matter" in complex biological and environmental samples. |

| CatBoost [2] | Software (ML) | Gradient boosting machine learning algorithm used for classification in virtual screening. | Offers optimal balance of speed and accuracy for screening billion-scale libraries. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [6] | Biophysical Instrument | Label-free measurement of biomolecular binding interactions, kinetics, and affinity. | Used for hit confirmation, characterizing binding events, and protein quality control. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [6] | Biophysical Instrument | Measures the heat change during binding to determine affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamics (ΔH). | Provides a full thermodynamic profile of a protein-ligand interaction. |

The framework of chemical space and the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) provides an indispensable paradigm for modern drug discovery. Moving from a theoretical universe to a practical research framework requires the integration of advanced computational methods—including machine learning-guided virtual screening and sophisticated chemical space comparison techniques—with rigorous experimental validation through biophysical and biochemical assays. The ongoing development of universal molecular descriptors, better coverage of underexplored regions like metallodrugs and macrocycles, and the generation of ever-more expansive yet synthetically accessible chemical libraries will continue to push the boundaries of the mappable BioReCS. This integrated approach, firmly grounded in the context of small molecule library research, powerfully accelerates the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents.

The systematic exploration of chemical space is a foundational pillar of modern chemical biology and drug discovery. The vastness of this space, estimated to contain over (10^{60}) drug-like molecules, makes experimental interrogation of even a minute fraction impractical. This challenge has been addressed over the last two decades by an explosion in the amount and type of biological and chemical data made publicly available in a variety of online databases [7]. These repositories have become indispensable for navigating the complex relationships between chemical structures, their biological activities, and their pharmacological properties. For researchers investigating small molecule libraries, these databases provide the essential data to understand Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR), perform virtual screening, and train machine learning models [8].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the core public compound databases, with a specific focus on their role in mapping the chemical space of small molecules. We will detail the defining features, curation philosophies, and use cases of two major public repositories—ChEMBL and PubChem—and then situate them within the broader ecosystem of specialized chemical databases. The content is framed within the context of chemical biology research, aiming to equip scientists and drug development professionals with the knowledge to strategically select and utilize these resources to accelerate their research.

Core Public Compound Databases

ChEMBL: A Manually Curated Resource for Bioactive Molecules

ChEMBL is a large-scale, open-access, manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [9] [10]. Hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), its primary mission is to aid the translation of genomic information into effective new drugs by bringing together chemical, bioactivity, and genomic data [9]. Since its first public launch in 2009, ChEMBL has grown into Europe's most impactful, open-access drug discovery database [11].

A key differentiator for ChEMBL is its emphasis on manual curation. Data are extracted from scientific literature, directly deposited by researchers, and integrated from other public resources, with human curators ensuring a high degree of reliability and standardization [7] [10]. The database is structured to be FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), and it employs a sophisticated schema to capture a wide array of data types, including targets, assays, documents, and compound information [11].

ChEMBL distinguishes between different types of molecules in its dictionary:

- Approved Drugs: Must come from a source of approved drug information (e.g., FDA, WHO ATC) and usually have indication and mechanism of action information. About 70% have associated bioactivity data [10].

- Clinical Candidate Drugs: Sourced from clinical candidate information (e.g., USAN, INN, ClinicalTrials.gov). About 40% have associated bioactivity data [10].

- Research Compounds: Must have bioactivity data, typically from scientific literature or direct depositions, but do not require a preferred name [10].

A significant feature introduced in ChEMBL 16 is the pChEMBL value, a negative logarithmic scale used to standardize roughly comparable measures of half-maximal response concentration, potency, or affinity (e.g., IC50, Ki), enabling easier comparison across different assays and compounds [11].

PubChem: A Comprehensive Repository of Chemical Information

PubChem is a widely used, open chemistry database maintained by the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [10] [12]. It is one of the largest public repositories, aggregating chemical structures and their associated biological activities from hundreds of data sources, including scientific literature, patent offices, and large-scale government screening programs [7] [12].

Unlike ChEMBL, PubChem operates primarily as a central aggregator where data are contributed by many different depositors and is not manually curated [10]. This model allows PubChem to achieve immense scale, containing more than 28 million entries as noted in a 2012 overview, though it continues to grow [7]. Its primary strength lies in its vastness and the diversity of its contributors, which includes data from ChEMBL itself [10]. PubChem makes extensive links between chemical structures and other data types, including biological activities, spectra, protein targets, and ADMET properties [7].

Comparative Analysis of ChEMBL and PubChem

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of ChEMBL and PubChem to facilitate a direct comparison.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of ChEMBL and PubChem

| Feature | ChEMBL | PubChem |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties & SAR data [9] | Comprehensive collection of chemical structures and properties [7] |

| Curation Model | Manual curation & integration [10] | Automated aggregation from multiple depositors [10] |

| Key Data Types | Bioactivity data (IC50, Ki, etc.), targets, mechanisms, drug indications, ADMET [11] | Chemical structures, bioactivity data, spectra, vendor information, patents [7] |

| Data Quality | High, due to manual curation and standardization [10] | Variable, depends on the original depositor [10] |

| Scope & Size | ~2.4 million research compounds, ~17.5k drugs/clinical candidates (ChEMBL 35) [10] | Vast; >28 million compounds (as of a 2012 overview, now larger) [7] |

| SAR Data | A core offering, explicitly curated [7] | Available, but not uniformly curated [7] |

| Unique Identifiers | CHEMBL[ID] (e.g., CHEMBL1715) [11] | CID (Compound ID) & SID (Substance ID) |

A Guide to Specialized Chemical Databases

Beyond the general-purpose giants, numerous specialized databases cater to specific research needs within chemical space. These resources often provide deeper, more focused data curation.

Table 2: Specialized Chemical Biology Databases

| Database | Availability | Primary Focus | Key Features | Relevance to Chemical Space |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DrugBank | Free for non-commercial use [10] | Drugs & drug targets [7] | Integrates drug data with target info, dosage, metabolism; not fully open-access [7] [10] | Defines the "druggable" subspace; links chemicals to clinical data. |

| GVK GOSTAR | Commercial [7] | SAR from medicinal chemistry literature [7] | Manually curated SAR, extensive annotations, links to toxicity/PK data [7] | High-quality SAR data for lead optimization. |

| ChemSpider | Free [7] | Chemical structures [7] | Community-curated structure database, links to vendors and spectra [7] | Extensive structure database with supplier information. |

| ZINC | Free [7] | Purchasable compounds for virtual screening [7] | Curated library of commercially available compounds, ready for docking [7] [8] | Represents the "purchasable" chemical space for virtual screening. |

| STITCH | Free [7] | Chemical-protein interactions [7] | Known and predicted interactions between small molecules and proteins [7] | Maps the interaction space between chemicals and the proteome. |

| ChEBI | Free [7] | Dictionary of small molecular entities [7] | Focused on chemical nomenclature and ontology [7] | Provides a structured vocabulary for describing chemical entities. |

Experimental Protocols for Database Mining

Leveraging these databases requires robust computational protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical virtual screening workflow that mines data from public databases.

Protocol: Integrated Virtual Screening Using Public Databases

Objective: To identify novel hit compounds for a target of interest by combining ligand-based and target-based screening strategies using public data.

Step 1: Target and Ligand Data Collection

- Query ChEMBL: Use the target's UniProt ID or name to retrieve all reported bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) [7]. Filter for high-confidence data (e.g.,

pChEMBL > 6). Export active compounds and their associated activity values. - Query PubChem: Perform a similar search to identify additional bioactivity data and associated chemical structures. Cross-reference results with ChEMBL to assess data consistency.

Step 2: Reference Set Curation and SAR Analysis

- Standardize Compounds: Process the collected active compounds (e.g., remove salts, neutralize charges, generate canonical SMILES) using a cheminformatics toolkit like RDKit.

- SAR Analysis: Cluster compounds based on molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4). Analyze activity cliffs and identify key functional groups contributing to potency. This defines the privileged chemotypes in the target's chemical space.

Step 3: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

- Similarity Search: Use one or more potent, structurally diverse actives identified in Step 2 as query molecules. Perform a Tanimoto-based similarity search against a large screening library (e.g., ZINC, PubChem) using molecular fingerprints [8].

- Physicochemical Filtering: Apply drug-likeness filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules) to the top-ranking compounds to focus on lead-like chemical space [8].

Step 4: Target-Based Virtual Screening (if a 3D structure is available)

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the target's 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prepare the structure (e.g., add hydrogens, assign protonation states, optimize side chains) using software like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard or UCSF Chimera.

- Molecular Docking: Dock the focused library from Step 3 against the prepared target structure using programs like AutoDock Vina or Glide. Rank compounds based on docking scores and inspect the predicted binding modes for key interactions.

Step 5: Triaging and Hit Selection

- Consensus Scoring: Prioritize compounds that rank highly in both ligand-based (high similarity) and structure-based (favorable docking score and pose) approaches.

- Patent Landscape Review: Use resources like SureChEMBL or commercial patent databases to check the novelty and intellectual property status of the prioritized hits [7].

- Purchasing/Testing: Finally, procure the top-ranked, novel compounds for experimental validation in biochemical or cell-based assays.

The Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software and database tools essential for executing the protocols above.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Database Mining

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, used for chemical structure standardization, fingerprint generation, and molecular descriptor calculation [8]. |

| ChemDoodle | Chemical Drawing & Informatics | A software tool for chemical structure drawing, visualization, and informatics, supporting structure searches and graphic production [13]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking Software | An open-source program for molecular docking, used for predicting how small molecules bind to a protein target [8]. |

| UniProt | Protein Database | A comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information, used for accurate target identification [7]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D Structure Database | A repository for 3D structural data of biological macromolecules, essential for structure-based drug design [7]. |

Visualizing the Data Ecosystem and Workflows

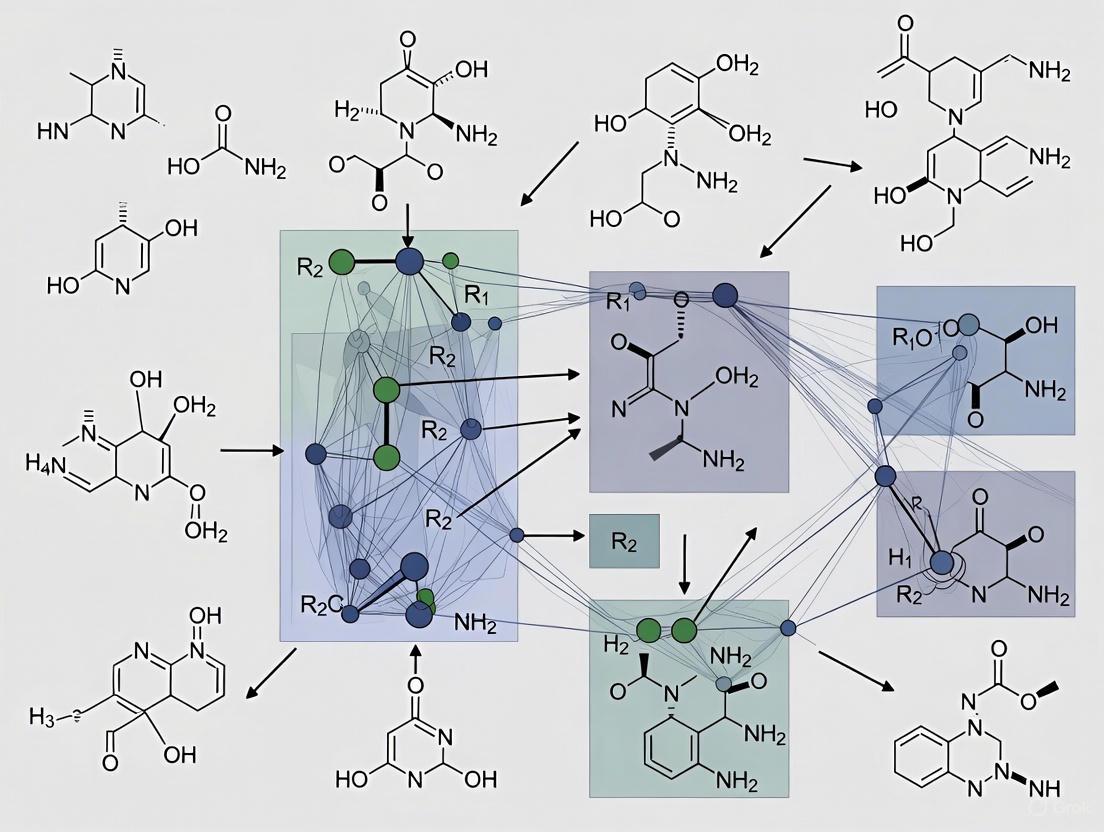

To effectively navigate the chemical database ecosystem, it is crucial to understand how these resources interconnect and support a typical research workflow. The diagram below maps the relationships and data flow between core and specialized databases.

Database Ecosystem for Chemical Space Research. This diagram illustrates the relationships between major public compound databases and the type of data they primarily contribute to the research ecosystem. Arrows indicate the flow of data and a typical research workflow.

The virtual screening process that leverages these databases can be conceptualized as a multi-stage funnel, depicted in the workflow below.

Virtual Screening Workflow Funnel. This diagram outlines the key stages of a virtual screening campaign, from initial data collection to final hit selection for experimental testing.

The landscape of public compound databases provides an unparalleled resource for probing the frontiers of chemical space. ChEMBL stands out for its high-quality, manually curated bioactivity and drug data, making it the resource of choice for SAR analysis and model training. In contrast, PubChem offers unparalleled scale and serves as a comprehensive aggregator of chemical information. The strategic researcher does not choose one over the other but uses them in a complementary fashion, leveraging ChEMBL's reliability for core analysis and PubChem's breadth for expanded context. This integrated approach, further enhanced by specialized resources like DrugBank for clinical insights or ZINC for purchasable compounds, empowers scientists to navigate chemical space with greater precision and efficiency. As these databases continue to grow and embrace FAIR principles, they will remain the bedrock upon which the next generation of data-driven drug discovery and chemical biology is built.

The concept of the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) serves as a foundational framework for modern drug discovery, representing the vast multidimensional universe of compounds with biological activity [1]. Within this space, molecular properties define coordinates and relationships, creating distinct regions or "subspaces" characterized by shared structural or functional features [1]. The systematic exploration of BioReCS enables researchers to identify promising therapeutic candidates while understanding the landscape of chemical diversity. This whitepaper examines the heavily explored regions dominated by traditional drug-like molecules alongside the emerging frontiers of PROTACs and metallodrugs, providing a comprehensive analysis of their characteristics, research methodologies, and potential for addressing unmet medical needs.

The contrasting exploration of these regions reflects both historical trends and technological capabilities. Heavily explored subspaces primarily consist of small organic molecules with favorable physicochemical properties that align with established rules for drug-likeness [3]. These regions are well-characterized and extensively annotated in major public databases such as ChEMBL and PubChem [1]. In contrast, underexplored regions encompass more complex chemical entities including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), metallodrugs, macrocycles, and beyond Rule of 5 (bRo5) compounds that present unique challenges for synthesis, analysis, and optimization [1]. Understanding the distinctions between these regions is crucial for directing future research efforts and expanding the therapeutic arsenal.

Heavily Explored Regions: The Drug-Like Chemical Space

Characteristics and Historical Development

The heavily explored regions of chemical space are predominantly occupied by small organic molecules with properties that align with established drug-likeness criteria. These regions have been extensively mapped through decades of pharmaceutical research and high-throughput screening efforts [3]. The evolution of this chemical subspace has been marked by significant technological advances since the 1980s, beginning with the revolution of combinatorial chemistry that progressed to the first small-molecule combinatorial library in 1992 [3]. This advancement, integrated with high-throughput screening (HTS) and computational methods, became fundamental to pharmaceutical lead discovery by the late 1990s [3].

Key characteristics of this heavily explored space include adherence to Lipinski's Rule of Five (RO5) parameters, which set fundamental criteria for oral bioavailability including molecular weight under 500 Daltons, CLogP less than 5, and specific limits on hydrogen bond donors and acceptors [3]. Additional guidelines have emerged for specialized applications, such as the "rule of 3" for fragment-based design and "rule of 2" for reagents, providing more targeted parameters for different molecular categories [3]. Assessment of ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties forms a crucial component of molecular evaluation in this space, with optimal passive membrane absorption correlating with logP values between 0.5 and 3, and careful attention paid to cytochrome P450 interactions and hERG channel binding risks [3].

Key Databases and Research Tools

The drug-like chemical space is richly supported by extensive, well-annotated databases and sophisticated research tools. Major public databases including ChEMBL (containing over 20 million bioactivity measurements for more than 2.4 million compounds) and PubChem serve as major sources of biologically active small molecules [1] [14]. These databases are characterized by their extensive biological activity annotations, making them valuable sources for identifying poly-active compounds and promiscuous structures [1].

Table 1: Major Public Databases for Heavily Explored Chemical Space

| Database | Size | Specialization | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | >2.4 million compounds | Bioactive drug-like molecules | Manually curated bioactivity data from literature; ~20 million bioactivity measurements |

| PubChem | Extensive collection | Broad chemical information | Aggregated data from multiple sources; biological activity annotations |

| DrugBank | Comprehensive | Drugs & drug targets | Combines chemical, pharmacological & pharmaceutical data |

| World Drug Index | ~5,822 compounds | Marketed drugs & developmental compounds | Historical data on ionizable drugs; 62.9% ionizable compounds |

Research methodologies in this space have evolved from traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) toward more sophisticated approaches including virtual screening, fragment-based drug design (FBDD), and lead optimization using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [3]. The success of this evolution is exemplified by landmark drugs such as Imatinib (Gleevec), which revolutionized chronic myeloid leukemia treatment, and Vemurafenib, which demonstrated the feasibility of targeting protein-protein interactions [3]. Despite these successes, challenges persist with only 1% of compounds progressing from discovery to approved New Drug Application (NDA), and a 50% failure rate in clinical trials due to ADME issues [3].

Underexplored Regions: Emerging Frontiers in Chemical Space

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras)

Mechanism and Design Principles

PROTACs represent a paradigm shift in therapeutic approach, moving beyond traditional occupancy-based inhibition toward active removal of disease-driving proteins [15]. These bifunctional molecules leverage the endogenous ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) to achieve selective elimination of target proteins [16] [17]. A canonical PROTAC comprises three covalently linked components: a ligand that binds the protein of interest (POI), a ligand that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and a linker that bridges the two [15]. The resulting chimeric molecule facilitates the formation of a POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex, leading to ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein via the 26S proteasome [15].

The degradation mechanism represents a fundamental advance in pharmacological strategy. Unlike traditional inhibitors that require sustained high concentrations to saturate and inhibit their targets, PROTACs function catalytically: they induce target degradation, dissociate from the complex, and can then catalyze multiple subsequent degradation cycles [17]. This sub-stoichiometric mode of action enables robust activity against proteins harboring resistance mutations and reduces systemic exposure requirements [15]. PROTAC technology has unlocked therapeutic possibilities for previously "undruggable" targets, including transcription factors like MYC and STAT3, mutant oncoproteins such as KRAS G12C, and scaffolding molecules lacking conventional binding pockets [15].

Clinical Progress and Applications

PROTAC technology has rapidly advanced from conceptual framework to clinical evaluation. The first PROTAC molecule entered clinical trials in 2019, and remarkably, just 5 years later, the field has achieved completion of Phase III clinical trials with formal submission of a New Drug Application to the FDA [15]. Clinical validation has been most compelling in oncology, where conventional approaches have repeatedly failed. For example, androgen receptor (AR) variants that drive resistance to standard antagonists remain susceptible to degradation-based strategies, and transcription factors such as STAT3—long considered among the most challenging cancer targets—are now tractable through systematic degradation [15].

Representative PROTAC candidates showing significant clinical promise include:

- ARV-110: Targeting androgen receptor for prostate cancer treatment

- ARV-471: Targeting estrogen receptor for breast cancer therapy

- BTK degraders: For hematologic malignancies targeting Bruton's tyrosine kinase

Building on these oncology successes, research has begun to explore applications beyond cancer, including neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, inflammatory conditions, and more recently, cellular senescence [15]. Each therapeutic area presents unique challenges in target selection, molecular design, and delivery, yet the technology demonstrates remarkable versatility across disease contexts.

Metallodrugs

Unique Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential

Metallodrugs represent a structurally and functionally important class of therapeutic agents that leverage the unique chemical properties of metal ions to exert cytotoxic effects on cancer cells [18]. These compounds offer a promising alternative to conventional organic chemotherapeutics, with cisplatin serving as the pioneering example that revolutionized cancer treatment by demonstrating significant efficacy against testicular and ovarian cancers [18] [19]. The mechanism of action of metallodrugs is intricately linked to their ability to interact with cellular biomolecules, particularly DNA [18].

Upon entering the cell, metallodrugs undergo aquation, where water molecules replace the leaving groups of the metal complex, activating the drug for interaction with DNA [18]. The activated metallodrugs then form covalent bonds with nucleophilic sites of the DNA, leading to the formation of intra-strand and inter-strand crosslinks that disrupt the helical structure of DNA, hindering replication and transcription processes, ultimately triggering apoptosis in cancer cells [18]. Beyond DNA targeting, many metallodrugs exhibit multifaceted mechanisms, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inhibition of key enzymes involved in cellular metabolism, and disruption of cellular redox homeostasis, further amplifying their anticancer effects [18].

Table 2: Representative Metallodrug Classes and Their Mechanisms

| Metal Center | Representative Drugs | Primary Mechanism | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum | Cisplatin, Carboplatin, Oxaliplatin | DNA crosslinking; disruption of replication | FDA-approved (1978, 1986, 1996) |

| Copper | Copper(II)-based complexes | Oxidative DNA cleavage; ROS generation | Preclinical investigation |

| Ruthenium | Numerous experimental compounds | Multiple mechanisms including DNA binding & enzyme inhibition | Clinical trials progression |

| Gold | Experimental complexes | Enzyme inhibition; mitochondrial targeting | Preclinical development |

Challenges and Innovative Solutions

Despite their therapeutic potential, metallodrugs face significant challenges in clinical translation. The development of drug resistance, primarily through enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, efflux pump activation, and alterations in drug uptake, poses a significant hurdle [18]. Furthermore, the inherent toxicity of metal ions requires careful dosing and monitoring to mitigate side effects such as nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and haematological toxicities [18] [19].

Innovative strategies are being explored to overcome these limitations. Targeted therapy represents a significant advancement, aiming to enhance selectivity and reduce systemic toxicity through conjugating metallodrugs with specific ligands or carriers that recognize and bind to cancer-specific biomarkers or receptors [18]. For instance, the conjugation of metallodrugs with peptides, antibodies, or nanoparticles enables targeted delivery to cancer cells, sparing normal tissues from collateral damage [18] [19]. These targeted metallodrug conjugates exhibit improved cellular uptake, prolonged circulation time, and enhanced accumulation at the tumour site through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [18]. Additionally, the development of prodrugs, which are inactive precursors that undergo enzymatic activation within the tumour microenvironment, has further refined the specificity and efficacy of metallodrug-based chemotherapy [18].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Advanced Screening Technologies

The exploration of underexplored chemical regions demands innovative screening methodologies that transcend traditional approaches. Barcode-free self-encoded library (SEL) technology represents a significant advancement, enabling direct screening of over half a million small molecules in a single experiment without the limitations imposed by DNA barcoding [20]. This platform combines tandem mass spectrometry with custom software for automated structure annotation, eliminating the need for external tags for the identification of screening hits [20]. The approach features the combinatorial synthesis of drug-like compounds on solid phase beads, allowing for a wide range of chemical transformations and circumventing the complexity and limitation of DNA-encoded library (DEL) preparation [20].

The SEL platform has demonstrated particular utility for challenging targets that are inaccessible to DEL technology. Application to flap endonuclease-1 (FEN1)—a DNA-processing enzyme not suited for DEL selections due to its nucleic acid-binding properties—resulted in the discovery of potent inhibitors, validating the platform's ability to access novel target classes [20]. The integration of advanced computational tools including SIRIUS 6 and CSI:FingerID for reference spectra-free structure annotation enables the deconvolution of complex screening results from libraries with high degrees of mass degeneracy [20].

Characterization and Analysis Methods

Characterizing complex chemical entities in underexplored regions requires specialized analytical approaches. For PROTACs, critical characterization includes assessment of ternary complex formation using techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and analytical ultracentrifugation, alongside evaluation of degradation efficiency through western blotting and cellular viability assays [15]. The "hook effect"—whereby higher concentrations paradoxically reduce degradation activity—presents a particular challenge that must be carefully evaluated during dose optimization [15].

For metallodrugs, comprehensive characterization necessarily involves advanced techniques including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry to elucidate coordination geometry and stability [18] [19]. The assessment of DNA binding properties through techniques like gel electrophoresis and atomic absorption spectroscopy for metal quantification provides crucial insights into mechanism of action [18]. Additionally, evaluation of cellular uptake, localization, and ROS generation potential helps establish structure-activity relationships for optimizing therapeutic efficacy [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Chemical Space Exploration

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Ligands (VHL, CRBN, IAP) | PROTAC Development | Recruit endogenous ubiquitin machinery | Selectivity, cell permeability, binding affinity |

| Target Protein Ligands | PROTAC Development | Bind protein of interest | High affinity, specificity, suitable binding site |

| Linker Libraries | PROTAC Optimization | Connect E3 ligand to target ligand | Length, flexibility, polarity, spatial orientation |

| Metal Salts & Complexes | Metallodrug Synthesis | Provide therapeutic metal centers | Stability, coordination geometry, redox activity |

| Organic Ligands | Metallodrug Development | Coordinate metal centers; influence properties | Denticity, hydrophobicity, biomolecular recognition |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Compound Annotation | Enable structural identification | Compatibility with ionization methods; coverage |

| Cell-Penetrating Agents | Cellular Assays | Enhance intracellular delivery | Cytotoxicity, efficiency, mechanism of uptake |

The exploration of BioReCS continues to evolve, with underexplored regions offering significant potential for addressing persistent challenges in drug discovery. PROTAC technology represents a fundamental paradigm shift from occupancy-based inhibition to event-driven pharmacology, demonstrating particular promise for targeting previously "undruggable" proteins [15]. With the first PROTAC molecules advancing through clinical trials and achieving Phase III completion, this approach is transitioning from innovative concept to therapeutic reality [15]. Similarly, metallodrugs continue to expand beyond traditional platinum-based compounds, with investigations into non-conventional metals and metalloid elements holding potential for addressing unmet clinical needs [18] [19].

Future advancements in both fields will require addressing persistent challenges. For PROTACs, these include optimizing molecular weight and polarity constraints that limit oral bioavailability, managing the "hook effect" in dose optimization, and developing robust predictive frameworks for identifying proteins amenable to degradation [15]. For metallodrugs, key challenges encompass overcoming drug resistance mechanisms, mitigating inherent toxicity of metal ions, and enhancing tumor selectivity through advanced targeting approaches [18]. The integration of innovative technologies including high-throughput screening, computational modeling, nanotechnology, and advanced delivery systems is expected to accelerate the development of next-generation therapeutics in these underexplored regions of chemical space [18] [21].

As chemical space continues to expand both in terms of cardinality and diversity, systematic approaches for navigation and prioritization become increasingly crucial. Quantitative assessment of chemical diversity using innovative cheminformatics methods like iSIM and the BitBIRCH clustering algorithm enables researchers to track the evolution of chemical libraries and identify regions warranting further exploration [14]. By strategically directing efforts toward underexplored yet biologically relevant regions of chemical space, researchers can unlock novel therapeutic opportunities and propel drug discovery into its next golden age.

In the age of artificial intelligence and large-scale data generation, the exploration of small molecule libraries has become a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. The concept of "chemical space" is a multidimensional universe where each molecule is positioned based on its structural and physicochemical properties, defined by numerical values known as molecular descriptors [1]. The ability to navigate this space effectively is crucial for identifying promising drug candidates, yet the high dimensionality of descriptor data presents a significant interpretation challenge.

Dimensionality reduction techniques address this challenge by transforming high-dimensional data into human-interpretable 2D or 3D maps, enabling researchers to visualize complex chemical relationships intuitively [22]. This process, often termed "chemography" by analogy to geography, has evolved from simple linear projections to sophisticated nonlinear mappings that better preserve the intricate relationships within chemical data [22]. Within the context of small molecule library research, these visualization approaches facilitate critical tasks such as library diversity assessment, hit identification, and property optimization.

This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications of dimensionality reduction for visualizing and interpreting the chemical space of small molecule libraries, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these techniques in drug discovery pipelines.

Molecular Descriptors: Defining the Dimensions of Chemical Space

Molecular descriptors are quantitative representations of molecular structures and properties that serve as the coordinates defining chemical space. The choice of descriptors significantly influences the topology and interpretation of the resulting chemical maps.

Descriptor Types and Categories

- Structural Fingerprints: Binary vectors indicating the presence or absence of specific substructures or patterns. MACCS keys are a prime example, encoding 166 predefined structural fragments [22].

- Circular Fingerprints: Encodings that capture atomic environments within a molecule. Morgan fingerprints (also known as Extended Connectivity Fingerprints) represent molecular topology by iteratively capturing circular neighborhoods around each atom up to a specified radius [22].

- Physicochemical Descriptors: Numerical representations of properties like molecular weight, logP, polar surface area, and hydrogen bond donors/acceptors. These often relate directly to drug-likeness criteria such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [3].

- Embeddings from Deep Learning: Continuous vector representations generated by neural networks. ChemDist embeddings, for instance, are obtained from graph neural networks trained using deep metric learning, where molecules are viewed as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [22].

Selection Criteria for Library Analysis

When working with small molecule libraries, descriptor selection should align with project goals. For large and ultra-large chemical libraries commonly used in contemporary drug discovery, descriptors must balance computational efficiency with chemical relevance [1]. Traditional descriptors tailored to specific chemical subspaces (e.g., small molecules, peptides, or metallodrugs) often lack universality, prompting development of more general-purpose descriptors like molecular quantum numbers and the MAP4 fingerprint [1].

Table 1: Common Molecular Descriptors for Chemical Space Analysis

| Descriptor Type | Dimensionality | Key Characteristics | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCS Keys | 166 bits | Predefined structural fragments; binary representation | Rapid similarity screening, substructure filtering |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Variable (typically 1024-2048) | Circular topology; capture atomic environments | Similarity search, scaffold hopping, diversity analysis |

| Physicochemical Properties | Typically 10-200 continuous variables | Directly interpretable; relates to drug-likeness | Library profiling, ADMET prediction, lead optimization |

| ChemDist Embeddings | 16 continuous dimensions | Neural network-generated; metric learning-based | Similarity-based virtual screening, novel analog generation |

Dimensionality Reduction Techniques: Core Methodologies

Dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques project high-dimensional descriptor data into 2D or 3D visualizations, each employing distinct mathematical frameworks with unique advantages for chemical space visualization.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a linear dimensionality reduction technique that identifies orthogonal axes of maximum variance in the data. It performs an eigendecomposition of the covariance matrix to find principal components that optimally preserve the global data structure [22] [23]. The method's linear nature makes it computationally efficient and easily interpretable, as principal components can often be traced back to original molecular features [23]. However, its linear assumption limits effectiveness for capturing complex nonlinear relationships prevalent in chemical space.

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE)

t-SNE is a nonlinear technique that focuses on preserving local neighborhood structures. It converts high-dimensional Euclidean distances between points into conditional probabilities representing similarities, then constructs a probability distribution over pairs of objects in the high-dimensional space [22]. In the low-dimensional map, it uses a Student-t distribution to measure similarity between points, which helps mitigate the "crowding problem" where nearby points cluster too tightly [22]. t-SNE excels at revealing local clusters and patterns but can distort global data structure.

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)

UMAP employs topological data analysis to model the underlying manifold of the data. It constructs a fuzzy topological structure in high dimensions then optimizes a low-dimensional representation to preserve this structure as closely as possible [22]. Based on Riemannian geometry and algebraic topology, UMAP typically preserves more of the global data structure than t-SNE while maintaining comparable local preservation capabilities [22] [23]. Its computational efficiency makes it suitable for large chemical datasets.

Generative Topographic Mapping (GTM)

GTM is a probabilistic alternative to PCA that models the data as a mixture of distributions centered on a latent grid. Unlike other methods that provide single-point projections, GTM generates a "responsibility vector" representing the association degree of each molecule to nodes on a rectangular map grid [24]. This fuzzy projection enables quantitative analysis of chemical space coverage and library comparison through responsibility pattern accumulation [24]. GTM is particularly valuable for establishing chemical space overlap considerations in library design.

Experimental Protocols for Chemical Space Visualization

Implementing robust dimensionality reduction for small molecule library analysis requires systematic protocols encompassing data preparation, algorithm configuration, and result validation.

Data Collection and Preprocessing Protocol

- Library Curation: Collect small molecule libraries from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL [22] [1], PubChem [1]) or proprietary sources. For combinatorial libraries, consider non-enumerative approaches using building blocks and reaction information [24].

- Standardization: Apply standardized chemical structure processing using tools like ChemAxon Standardizer. This typically includes dearomatization and final aromatization (with exceptions for heterocycles like pyridone), dealkalization, conversion to canonical SMILES, removal of salts and mixtures, neutralization of all species (except nitrogen(IV)), and generation of the major tautomer [24].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors using chemoinformatics toolkits like RDKit. For Morgan fingerprints, common parameters include radius 2 and fingerprint size 1024 [22]. Remove all zero-variance features to improve computational efficiency.

- Data Standardization: Apply feature-wise standardization (z-score normalization) to all descriptors before dimensionality reduction to ensure equal weighting of variables with different scales [22].

Dimensionality Reduction Implementation

- Algorithm Selection: Choose DR methods based on library characteristics and analysis goals. For initial exploration, PCA provides a computationally efficient overview. For cluster identification, t-SNE or UMAP may be preferable. For quantitative space coverage analysis, GTM offers unique advantages [24] [22].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Conduct grid-based search to optimize method-specific parameters using neighborhood preservation metrics. For UMAP, key parameters include number of neighbors, minimum distance, and metric. For t-SNE, perplexity and learning rate significantly impact results [22].

- Model Training: Apply the DR algorithm to the standardized descriptor matrix. For large combinatorial libraries where enumeration is infeasible, employ specialized tools like CoLiNN (Combinatorial Library Neural Network) that predict compound projections using only building blocks and reaction information [24].

- Projection Generation: Transform the high-dimensional data into 2D or 3D coordinates. For GTM, this generates responsibility vectors rather than single points [24].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for chemical space visualization of small molecule libraries, covering data preprocessing, dimensionality reduction, and applications in drug discovery.

Validation and Evaluation Metrics

- Neighborhood Preservation Analysis: Quantify how well the low-dimensional projection preserves neighborhoods from the original high-dimensional space using metrics such as:

- PNNk: Average percentage of preserved k-nearest neighbors between original and latent spaces [22].

- Co-k-nearest neighbor size (QNN): Measures neighborhood preservation within a given tolerance up to rank k [22].

- Trustworthiness and Continuity: Evaluate whether the projection maintains original data relationships without introducing false structures [22].

- Visual Diagnostic Assessment: Apply scatterplot diagnostics (scagnostics) to quantitatively assess visualization characteristics relevant to human perception, including clustering patterns, outliers, and shape attributes [22].

Comparative Analysis of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

Evaluating DR method performance requires systematic assessment across multiple criteria relevant to small molecule library analysis.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for Chemical Space Visualization

| Method | Neighborhood Preservation | Global Structure | Local Structure | Computational Efficiency | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Moderate | Excellent | Moderate | High | High |

| t-SNE | High | Poor | Excellent | Moderate | Moderate |

| UMAP | High | Good | Excellent | Moderate | Moderate |

| GTM | High | Good | Good | Moderate | High |

Method Selection Guidelines

- For Large Combinatorial Libraries: GTM demonstrates particular utility for visualizing DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) and other large combinatorial spaces, especially when using non-enumerative approaches like CoLiNN [24].

- For Cluster Identification: UMAP and t-SNE outperform linear methods in revealing chemically meaningful clusters in target-specific compound sets from databases like ChEMBL [22].

- For Explainable Projections: PCA maintains advantages when interpretability of projection axes is prioritized, as its linear nature allows tracing back to original molecular features [23].

Advanced Applications in Small Molecule Library Research

Non-Enumerative Visualization of Combinatorial Libraries

Traditional visualization requires full library enumeration, which becomes computationally prohibitive for large combinatorial spaces. The Combinatorial Library Neural Network (CoLiNN) addresses this by predicting compound projections using only building block descriptors and reaction information, eliminating enumeration requirements [24]. In benchmark studies, CoLiNN demonstrated high predictive performance for DNA-Encoded Libraries containing up to 7 billion compounds, accurately reproducing projections obtained from fully enumerated libraries [24].

Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) Mapping

Dimensionality reduction enables visualization of the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) - regions containing molecules with biological activity [1]. By projecting libraries alongside bioactive reference sets (e.g., ChEMBL, DrugCentral), researchers can assess potential biological relevance of unexplored regions. This approach facilitates targeted library design for specific target classes or mechanisms of action.

Integration with Deep Learning Approaches

Modern dimensionality reduction increasingly integrates with deep learning frameworks. Chemical language models generate molecular embeddings that serve as input to DR techniques, creating visualizations that capture complex structural and property relationships [1] [3]. These approaches support chemography-informed generative models that explore targeted regions of chemical space for specific therapeutic applications [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Chemical Space Visualization

Implementing chemical space visualization requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key solutions relevant to dimensionality reduction in small molecule library research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Space Visualization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source toolkit | Cheminformatics functionality, descriptor calculation | Structure standardization, fingerprint generation, property calculation |

| scikit-learn | Python library | Machine learning algorithms | PCA implementation, data preprocessing, model validation |

| OpenTSNE | Python library | Optimized t-SNE implementation | Efficient t-SNE projections with various parameterizations |

| umap-learn | Python library | UMAP implementation | Manifold learning-based dimensionality reduction |

| CoLiNN | Specialized neural network | Non-enumerative library visualization | Combinatorial library projection without compound enumeration |

| ChEMBL | Public database | Bioactive molecule data | Reference sets for biologically relevant chemical space |

| GTM | In-house algorithm | Probabilistic topographic mapping | Fuzzy chemical space projection with responsibility vectors |

Dimensionality reduction techniques represent indispensable tools for navigating the complex multidimensional landscapes defined by small molecule libraries. As chemical spaces continue to expand through advances in combinatorial chemistry and virtual compound generation, effective visualization methodologies will play an increasingly critical role in drug discovery. The ongoing development of non-enumerative approaches like CoLiNN and integration with deep learning frameworks heralds a new era of chemical space exploration, where researchers can efficiently map billion-compound libraries to identifiable regions of biological relevance. By selecting appropriate molecular descriptors, implementing robust experimental protocols, and applying method-specific validation metrics, research teams can leverage these powerful visualization approaches to accelerate the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents.

In the pursuit of novel bioactive molecules, the research community has historically prioritized "active" compounds, relegating negative data to the background. This whitepaper articulates a paradigm shift, underscoring the indispensable value of negative data—encompassing both inactive compounds and Dark Chemical Matter (DCM)—within small molecule libraries for chemical space research. Inactive compounds are those rigorously tested and found to lack activity in specific assays, while DCM refers to the subset of drug-like molecules that have never shown activity across hundreds of high-throughput screens despite extensive testing [26]. The systematic incorporation of these data types is not merely an exercise in data curation; it is a foundational strategy for refining predictive models, de-risking drug discovery campaigns, and illuminating the complex boundaries of the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) [27] [1]. This document provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the conceptual framework, practical applications, and experimental protocols for leveraging negative data to accelerate the discovery of high-quality lead molecules.

The concept of chemical space, a multidimensional representation where molecules are positioned based on their structural and physicochemical properties, provides a powerful framework for modern drug discovery. Within this vast universe, the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) constitutes all molecules with a documented biological effect [1]. Traditional exploration has focused on the bright, active regions of this space. However, a complete map requires an understanding of both the active and inactive regions.

- Inactive Compounds: These are compounds that have been experimentally tested in a specific assay and have demonstrated no significant activity above a pre-established, often subjective, cut-off value. Their designation is context-dependent, based on the assay's biological endpoint and the research project's goals [27].

- Dark Chemical Matter (DCM): DCM is a particularly rigorous sub-class of inactive compounds. It consists of small molecules that possess excellent drug-like properties and selectivity profiles but have never shown bioactivity in any of the hundreds of HTS assays they have been subjected to within corporate or academic collections [28] [26]. Their persistent inactivity makes them exceptionally valuable.

- Structure-Inactivity Relationships (SIRs): Analogous to Structure-Activity Relationships (SARs), SIRs are the systematic studies that rationalize the lack of activity of a compound or a chemical series. Generating solid hypotheses for why a compound is inactive is a critical scientific endeavor [27].

The under-reporting of negative data creates significant public domain challenges. It leads to highly imbalanced datasets, which in turn limit the development and refinement of robust predictive models in computer-aided drug design (CADD) [27]. Embracing negative data is essential for a true understanding of the structure-property relationships that govern BioReCS.

The Strategic Value of Negative Data in Drug Discovery

Enhancing Predictive Modeling and Machine Learning

The availability of high-quality, balanced datasets containing both active and inactive compounds is a principal limitation in developing descriptive and predictive models [27]. Inactive data are indispensable for:

- Model Validation: They are crucial for evaluating the performance of machine learning algorithms and virtual screening tools. Benchmark sets like MoleculeNet rely on confirmed inactive compounds to provide realistic assessments of model accuracy [27].

- Defining Chemical Boundaries: Inactive data help delineate the structural and physicochemical boundaries that separate bioactive from non-bioactive regions in chemical space. This allows for the identification of "inactive scaffolds" and undesirable properties that should be avoided in design [27].

- Advanced Generative Models: Emerging techniques like Molecular Task Arithmetic leverage abundant negative data to learn "property directions" in a model's weight space. By moving away from these negative directions, models can generate novel, active molecules in a zero-shot or few-shot learning context, overcoming the scarcity of positive data [29].

De-risking Discovery and Identifying Quality Starting Points

The use of negative data directly impacts the efficiency and success of discovery campaigns.

- Mitigating Interference: Libraries pre-filtered for pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) and other problematic functionalities reduce false positives in HTS, saving time and resources [30].

- Uncovering Unique Chemotypes: Surprisingly, compounds from DCM collections can occasionally yield potent, unique hits with clean safety profiles when tested in novel assays. This is because their pristine inactivity record suggests high selectivity, minimizing the risk of off-target effects. A notable example is the discovery of a new antifungal chemotype from a DCM library that was active against Cryptococcus neoformans but showed little activity against human safety targets [26].

- Informing Lead Optimization: Understanding SIRs helps guide medchem efforts away from structural features associated with inactivity or undesired properties, making the hit-to-lead process more efficient [27].

Table 1: Publicly Available Databases Containing Negative Data for BioReCS Exploration

| Database Name | Content Focus | Relevance to Negative Data |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [1] | Bioactive drug-like small molecules | Contains some negative data and is a major source for poly-active and promiscuous compounds. |

| PubChem [1] | Small molecules and their biological activities | A key resource that includes bioactivity data, which can be curated to identify inactive compounds. |

| InertDB [1] | Curated inactive compounds | A specialized database containing 3,205 curated inactive compounds from PubChem and 64,368 AI-generated putative inactives. |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) Libraries [28] [26] | Compounds inactive across many HTS assays | Collections of highly selective, drug-like compounds that have never shown activity in historical screening data. |

Exploring the "Dark" Regions of Excipients and Metabolites

The principle of analyzing "inactive" components extends beyond primary screening libraries.

- Drug Excipients: Traditionally considered inert, many excipients have been found to have activities on physiologically relevant targets. Systematic in vitro screening has revealed that excipients like propyl gallate (antioxidant) and various dyes can modulate targets such as COMT and transporters like OATP2B1 at low micromolar concentrations [31]. This has profound implications for drug formulation and safety.

- Drug Metabolites: Understanding whether a drug's metabolites are active or inactive is a cornerstone of pharmacology. Inactive metabolites (e.g., those of acetaminophen) are broken down forms with no significant biological effect, while active metabolites (e.g., morphine from codeine) can produce or enhance therapeutic and toxic effects [32].

Experimental Protocols for Leveraging Negative Data

Protocol 1: Virtual Screening of Dark Chemical Matter Libraries

This protocol, adapted from a study that discovered a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor, outlines the steps for a robust virtual screening campaign using a DCM library [28].

Objective: To identify novel inhibitors of a biological target from a DCM database. Key Reagent: A curated DCM library (e.g., the Dark Chemical Matter database [28]).

- Target Preparation: Generate an ensemble of representative receptor conformations (e.g., from crystal structures or molecular dynamics simulations) to account for protein flexibility. The referenced study used seven representative structures of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro monomer [28].

- Ensemble Molecular Docking: Perform docking of the entire DCM library against each representative receptor structure.

- Use multiple docking scoring functions to mitigate scoring bias. The protocol employs two independent strategies:

- Dock1: Standard scoring function (e.g., QVina2).

- Dock2: Size-independent scoring, where the default score is divided by the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the ligand to the power of 0.3 [28].

- Use multiple docking scoring functions to mitigate scoring bias. The protocol employs two independent strategies:

- Pose Selection and Minimization: From each docking run, select ligand-receptor complexes that meet a defined scoring threshold. Subject these complexes to energy minimization in an explicit solvent model to relieve steric clashes and bad contacts.

- Binding Affinity Assessment: Calculate the binding free energy of the minimized complexes using end-point methods such as MMPBSA and MMGBSA.

- Consensus Ranking and Selection: Generate ranked lists from the previous step. Prioritize compounds that consistently appear across different receptor conformations and scoring methods. Select the top-ranking compounds for experimental validation.

The workflow is designed to identify those rare compounds in the DCM that have a genuine potential for binding to the target of interest.

Protocol 2: Cheminformatic Analysis of Structure-Inactivity Relationships

This protocol describes a computational workflow for analyzing and visualizing the chemical space of inactive compounds relative to their active counterparts [27] [33] [1].

Objective: To identify structural features and chemical subspaces associated with a lack of biological activity. Key Reagent: A balanced dataset containing both active and inactive compounds for a target or target class.

- Data Curation and Preparation: Compile a dataset with confirmed active and inactive compounds. Standardize structures and calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological polar surface area) or fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MAP4).

- Chemical Space Visualization: Project the compounds into a low-dimensional space to visualize the distribution of actives and inactives.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): To view the overall distribution of compounds.

- Self-Organizing Maps (SOM): An unsupervised learning method to create a 2D representation that groups similar molecules together in nodes [33].

- MCS Dendrogram: A tree-based visualization that clusters compounds based on their Maximum Common Substructure (MCS), helping to identify inactive scaffolds [33].

- Identify Inactive Substructures: Analyze the clusters and nodes dominated by inactive compounds to pinpoint common substructures or functional groups associated with inactivity. This can be done by visual inspection or using algorithmic substructure mining.

- Model Building: Use the labeled data to train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) to predict activity versus inactivity. The model's features can provide insight into the molecular properties critical for activity.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Resources for Negative Data Research

| Tool/Resource Category | Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [27] [1], PubChem [1] | Sources for obtaining experimentally determined inactive compound data. |

| Specialized Negative Data Libraries | InertDB [1], Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) Libraries [28] [26] | Curated collections of confirmed inactive or never-active compounds for model training and screening. |

| Cheminformatics Software Suites | MOE, Schrodinger, OpenEye [30] | Platforms for calculating molecular descriptors, applying filters, and performing diversity analysis. |

| Chemical Space Visualization Tools | ICM-Chemist [33], RDKit | Software capable of generating MCS Dendrograms, Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), and PCA plots. |

| Machine Learning Benchmarks | MoleculeNet [27] | A benchmark dataset that includes inactive compounds to evaluate the performance of machine learning algorithms. |

The integration of negative data into the drug discovery lifecycle is transitioning from a best practice to a critical necessity. Inactive compounds and Dark Chemical Matter are not merely null results; they are rich sources of information that define the non-bioactive chemical space, thereby sharpening our search for quality leads. The ongoing development of public repositories like InertDB, combined with advanced AI methodologies like molecular task arithmetic that creatively leverage negative data, points to a future where the "dark" regions of chemical space are fully illuminated and strategically exploited [1] [29].

To fully realize this potential, a cultural shift is required. Scientists, reviewers, and editors must collectively champion the disclosure and dissemination of high-confidence negative data. By systematically incorporating structure-inactivity relationships into our research frameworks, we can more efficiently navigate the biologically relevant chemical space, reduce attrition in late-stage development, and ultimately increase the throughput of discovering safer and more effective therapeutics.

Next-Generation Library Technologies: From DELs to Barcode-Free Screening and AI

DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) technology represents a transformative approach in modern drug discovery, providing an efficient and universal platform for identifying novel lead compounds that significantly advance pharmaceutical development [34]. The fundamental concept of DELs was first proposed in a seminal 1992 paper by Professor Richard A. Lerner and Professor Sydney Brenner, who established a 'chemical central dogma' within the DEL system where oligonucleotides function as amplifiable barcodes (genotype) for their corresponding small molecules or peptides (phenotypes) [35]. This innovative framework creates a direct linkage between chemical structures and their DNA identifiers, enabling the efficient screening of vast molecular collections against biological targets. The technology has progressively evolved from an academic concept to an indispensable tool in the pharmaceutical industry, with the first International Symposium on DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries initiated in 2006 by Professor Dario Neri and Professor Jörg Scheuermann, reflecting the growing importance of this field [34].

The core principle of DEL technology revolves around combining combinatorial chemistry with DNA encoding to create extraordinarily diverse molecular libraries that can be screened en masse through affinity selection. Each compound in the library is covalently attached to a unique DNA barcode that records its synthetic history, enabling deconvolution of hit structures after selection [36]. This approach allows researchers to screen libraries containing billions to trillions of compounds in a single tube, dramatically reducing the resource requirements compared to traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) methods [20]. The DNA barcode serves as an amplifiable identification tag that can be decoded via high-throughput sequencing after selection against a target of interest, providing a powerful method for navigating expansive chemical space with unprecedented efficiency.

DEL technology has garnered substantial interest from both academic institutions and pharmaceutical companies due to its revolutionary potential in reshaping the drug discovery paradigm [34]. Major global pharmaceutical entities including AbbVie, GSK, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca, along with specialized DEL research and development enterprises such as X-Chem, WuXi AppTec, and HitGen, have actively integrated DEL platforms into their discovery workflows [34]. The ongoing refinement of DEL methodologies has progressively shifted the technology from initial empirical screening approaches toward more rational and precision-oriented strategies that enhance hit quality and screening efficiency [36].

DEL Technology Workflow: From Library Design to Hit Identification

The process of employing DNA-Encoded Libraries for lead discovery follows a systematic workflow encompassing library design, combinatorial synthesis, affinity selection, hit decoding, and validation. This integrated approach enables researchers to efficiently navigate massive chemical spaces and identify promising starting points for drug development programs.

Library Design and DNA-Compatible Synthesis

The construction of a DNA-Encoded Library begins with careful design and execution of combinatorial synthesis using DNA-compatible chemistry. Library synthesis typically employs a split-and-pool approach where each chemical building block incorporation is followed by the attachment of corresponding DNA barcodes that record the synthetic transformation [35]. This strategy enables the efficient generation of library diversity while maintaining the genetic record of each compound's structure. For instance, a library with three synthetic cycles using 100 building blocks at each stage would generate 1,000,000 (100³) distinct compounds, each tagged with a unique DNA sequence encoding its synthetic history.

A critical consideration in DEL synthesis is the requirement for DNA-compatible reaction conditions that preserve the integrity of the oligonucleotide barcodes. Traditional organic synthesis often employs conditions that degrade DNA, necessitating the development and optimization of specialized reactions that proceed efficiently in aqueous environments at moderate temperatures and pH [20]. Significant advances have been made in expanding the toolbox of DNA-compatible transformations, including:

- Copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) for regioselective generation of 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles [35]

- Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Sonogashira) for carbon-carbon bond formation [35]

- Amide bond formation and nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions [20]

- Photocatalysis and C-H activation methodologies for accessing novel chemical space [35]

Recent innovations have further enhanced DEL capabilities through approaches such as Selenium-based Nitrogen Elimination (SeNEx) chemistry, core skeleton editing, machine learning-guided building block selection, and flow chemistry applications [35]. These developments have significantly expanded the structural diversity and drug-like properties of DEL compounds while maintaining compatibility with the DNA encoding system.

Affinity Selection and Hit Identification

Following library synthesis, the DEL undergoes affinity selection against a target protein of interest. In this process, the target is typically immobilized on a solid support and incubated with the DEL, allowing potential binders to interact with the protein [20]. Unbound compounds are removed through rigorous washing steps, while specifically bound ligands are eluted and their DNA barcodes amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The amplified barcodes are then sequenced using high-throughput sequencing technologies, and bioinformatic analysis decodes the chemical structures of the enriched compounds based on their corresponding DNA sequences.