Mastering Experimental Design for Source of Variation Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design robust experiments that effectively identify, quantify, and control sources of variation.

Mastering Experimental Design for Source of Variation Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design robust experiments that effectively identify, quantify, and control sources of variation. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, it explores methodological approaches like Design of Experiments (DoE) and variance component analysis, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and validation techniques for comparative studies. The guide synthesizes principles from omics research, pharmaceutical development, and clinical trials to empower scientists in building quality into their research, minimizing bias, and drawing reliable, reproducible conclusions from complex data.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles for Identifying Sources of Variation

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the major sources of variability in biological experiments? The hierarchy of variability spans from molecular differences between individual cells to significant differences between patients. The greatest source of variability often comes from biological factors such as tissue heterogeneity (different regions of the same biopsy) and inter-patient variation, rather than technical experimental error [1]. Even in relatively homogeneous tissues like muscle, different biopsy regions show substantial variation in cell type content [1].

Why do my cultured cell results not translate to primary tissues? Cultured cells exhibit fundamentally different biology from primary tissues. Lipidomic studies reveal that primary membranes (e.g., erythrocytes, synaptosomes) sharply diverge from all cultured cell lines, with primary tissues containing more than double the abundance of highly unsaturated phospholipids [2]. This "unnatural" lipid composition in cultured cells is likely driven by standard culture media formulations lacking polyunsaturated fatty acids [2].

How can I minimize variability in expression profiling studies? Pre-profile mixing of patient samples can effectively normalize both intra- and inter-patient sources of variation while retaining profiling specificity [1]. One study found that experimental error (RNA, cDNA, cRNA, or GeneChip) was minor compared to biological variability, with mixed samples maintaining 85-86% of statistically significant differences detected by individual profiles [1].

How do I troubleshoot failed PCR experiments? Follow a systematic approach: First, identify the specific problem (e.g., no PCR product). List all possible causes including each master mix ingredient, equipment, and procedure. Collect data by checking controls, storage conditions, and your documented procedure. Eliminate unlikely explanations, then design experiments to test remaining possibilities [3].

What should I do when no clones grow on my transformation plates? Check your control plates first. If colonies grow on controls, the problem likely lies with your plasmid, antibiotic, or transformation procedure. Systematically test your competent cell efficiency, antibiotic selection, heat shock temperature, and finally analyze your plasmid DNA for integrity and concentration [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Systematic Troubleshooting for Failed Experiments

Problem Identification

- Define the specific failure: Precisely note what went wrong without assuming causes [3]

- Check controls first: Determine if positive/negative controls worked as expected [3]

- Document everything: Record all observations in your laboratory notebook [4]

Root Cause Analysis

Implementation and Verification

- Design targeted experiments to test remaining hypotheses [3]

- Change one variable at a time while keeping others constant [4]

- Verify the solution by reproducing results multiple times [4]

- Document the resolution for future reference [3]

Guide 2: Addressing Cell Line vs. Primary Tissue Discrepancies

Recognizing the Limitations of Cultured Cells

Table 1: Key Lipidomic Differences Between Cultured Cells and Primary Tissues

| Lipid Characteristic | Cultured Cells | Primary Tissues | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyunsaturated Lipids | Low abundance (<10%) | High abundance (>20%) | Membrane fluidity, signaling |

| Mono/Di-unsaturated Lipids | High abundance | Lower abundance | Membrane physical properties |

| Plasmenyl Phosphatidylcholine | Relatively abundant | Scarce in primary samples | Oxidative protection |

| Sphingomyelin Content | Variable | Tissue-specific enrichment | Membrane microdomains |

Experimental Strategies to Bridge the Gap

- Supplement culture media with polyunsaturated fatty acids to better recapitulate in vivo conditions [2]

- Validate key findings in multiple model systems including primary cells [2]

- Consider tissue-specific lipidomics when designing drug delivery systems [2]

- Account for donor variability by using multiple primary sources [1]

Guide 3: Managing Variability in Expression Profiling

Understanding Variability Sources

Table 2: Relative Contribution of Different Variability Sources in Expression Profiling

| Variability Source | Relative Impact | Management Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Heterogeneity (different biopsy regions) | Highest | Sample mixing, multiple biopsies |

| Inter-patient Variation (SNP noise) | High | Larger sample sizes, careful matching |

| Experimental Procedure (RNA/cRNA production) | Moderate | Standardized protocols, quality control |

| Microarray Hybridization | Low | Technical replicates, normalization |

Protocol: Sample Mixing for Variability Normalization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Variability Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Lipidomics (ESI-MS/MS) | Comprehensive lipid profiling | Measures 400-800 individual lipid species per sample; reveals membrane composition differences [2] |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Dimensionality reduction for complex datasets | Identifies major sources of variation; compresses lipidomic variation into interpretable components [2] |

| Affymetrix GeneChips | Expression profiling platform | Provides standardized, redundant oligonucleotide arrays for transportable data [1] |

| Premade Master Mixes | PCR reaction consistency | Reduces experimental error compared to homemade mixes [3] |

| Quality Controlled Competent Cells | Reliable transformation | Maintain transformation efficiency for at least one year with proper storage [3] |

Advanced Technical Notes

Protocol: Shotgun Lipidomics for Membrane Variability Analysis

Sample Preparation

- Isolate membranes using standardized protocols (plasma membrane vs. whole cell membranes)

- Extract lipids maintaining consistency across samples

- Include quality controls from reference materials

ESI-MS/MS Analysis

- Utilize electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry

- Quantify 400-800 individual lipid species per sample

- Measure abundance from 0.001 mol% to 40 mol% (cholesterol)

Data Interpretation

- Perform PCA to identify major sources of variation

- Analyze both phospholipid headgroups and total lipid unsaturation

- Compare loadings to understand segregating features [2]

Protocol: Managing Inter-patient Variability in Human Studies

Experimental Design

- Collect multiple biopsies from each patient when possible

- Process RNAs individually initially

- Use mixing strategies to normalize SNP noise

- Maintain strict quality control criteria

Quality Control Parameters

- Sufficient cRNA amplification

- Post-hybridization scaling factors (ideal range: 0.5-3.0)

- Percentage present calls consistency

- Correlation coefficients between replicates [1]

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between a biological and a technical replicate?

A biological replicate is a distinct, independent biological sample (e.g., different mice, independently grown cell cultures, or different human patients) that captures the random biological variation found in the population or system under study. In contrast, a technical replicate is a repeated measurement of the same biological sample. It helps quantify the variability introduced by your measurement technique itself, such as pipetting error or instrument noise [5] [6].

2. What is pseudoreplication and why is it a problem?

Pseudoreplication occurs when technical replicates are mistakenly treated as if they were independent biological replicates [6]. This is a serious error because it artificially inflates your sample size in statistical analyses. Treating non-independent measurements as independent increases the likelihood of false positive results (Type I errors), leading you to believe an experimental effect is real when it may not be [6].

3. How many technical replicates are optimal for evaluating my measurement system?

For experiments designed to evaluate the reproducibility or reliability of your measurements (often called "Type B" experiments), the optimal allocation is to use two technical replicates for each biological replicate when the total number of measurements is fixed. This configuration minimizes the variance in estimating your measurement error [7].

4. Can I use technical replicates to increase my statistical power for biological questions?

Not directly. Technical replicates primarily help you understand and reduce the impact of measurement noise. For statistical analyses that ask biological questions (e.g., "Does this treatment change gene expression?"), the sample size (n) is the number of biological replicates, not the total number of measurements. To increase power for these "Type A" experiments, you should increase the number of biological replicates [7] [6].

5. My samples are very expensive, but assays are cheap. Can I just run many technical replicates?

While you can, it will not help you generalize your findings. If you use only one biological replicate (e.g., cells from a single donor) with many technical replicates, your conclusions are only valid for that one donor. You cannot know if the results apply to the broader population. A better strategy is to find a balance, perhaps using a moderate number of biological replicates with a smaller number of technical replicates to control measurement error [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios

| Scenario | Potential Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability between technical replicates. | Your measurement protocol or instrumentation may be unstable or imprecise [5]. | Review and optimize your assay protocol. Check instrument calibration. Use technical replicates to identify and reduce sources of measurement error. |

| No statistical significance despite large observed effect. | Likely due to too few biological replicates, resulting in low statistical power [6]. | Increase the number of independent biological replicates. Statistical power is driven by the number of biological, not technical, replicates. |

| Statistical analysis shows a significant effect, but the result does not hold up in a follow-up experiment. | Potential pseudoreplication. Treating technical replicates or non-independent samples as biological replicates inflates false positive rates [6]. | Re-analyze your data, ensuring the statistical n matches the number of true biological replicates. Use mixed-effects models if non-independence is inherent to the design. |

| Uncertainty in whether a sample is a true biological replicate. | The definition might be unclear for complex experimental designs (e.g., cells from the same tissue culture flask, pups from the same litter) [6]. | Apply the three criteria for true biological replication: 1) Random assignment to conditions, 2) Independent application of the treatment, and 3) Inability of individuals to affect each other's outcome. |

Experimental Protocols for Proper Replication

Protocol 1: Establishing a Valid Replication Strategy

- Define Your Experimental Unit: Identify the smallest independent entity to which a treatment can be applied. This is your potential biological replicate (e.g., a single mouse, a culture of cells seeded from an independent vial, a separately transfected well).

- Apply Treatments Independently: Ensure that the treatment for one biological replicate does not depend on and is not applied simultaneously with another. For example, treat cells in separate culture vessels with individually prepared drug dilutions rather than adding one concentration to a shared bath.

- Prevent Cross-Influence: House animals or process samples in a way that prevents one from influencing the other. This may require separate caging or independent processing [6].

- Determine Replicate Numbers:

- Biological Replicates: Plan for a sufficient number based on a power analysis. This is the most critical factor for the validity of your biological conclusions.

- Technical Replicates: For assessing measurement reliability, use two per biological sample [7]. For routine experiments, duplicate or triplicate technical measurements can help control for assay-level variability.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Western Blot Analysis with Replicate Samples

This protocol exemplifies how to integrate both replicate types for robust quantification [5].

- Prepare Biological Replicates: Culture and treat cells in at least three independent batches (biological replicates

n=3). - Prepare Technical Replicates: For each biological sample, prepare two or more separate protein lysates (technical replicate 1). Load each lysate onto the same gel or parallel gels (technical replicate 2).

- Image and Quantify: Detect bands and quantify signal intensity.

- Analyze Data: Normalize target protein signal to a validated loading control. First, average the technical replicate measurements for each biological sample. Then, perform statistical comparisons across the means of the independent biological replicates (

n=3).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Independently Cultured Cell Batches | The foundation of in vitro biological replication. Cells cultured and passaged separately mimic population-level variation. |

| Genetically Distinct Animal Models | Crucial for in vivo biological replication. Using different animals accounts for genetic and physiological variability. |

| Revert 700 Total Protein Stain | A superior normalization method for Western blotting. Stains all proteins, providing a more reliable loading control than a single housekeeping protein [5]. |

| Validated Housekeeping Antibodies | Used for traditional Western blot normalization. Must be validated to confirm their expression is constant across all experimental conditions [5]. |

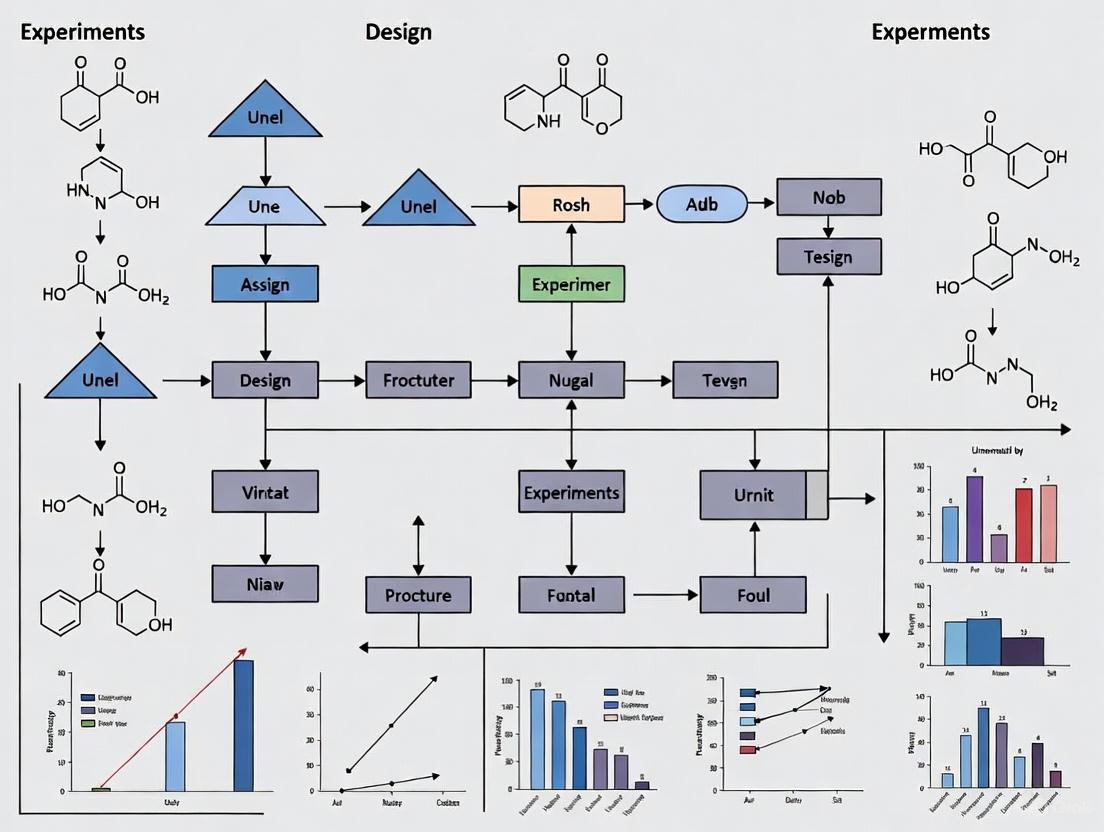

Relationships and Workflow Diagrams

The following diagrams, created using DOT language, illustrate the core concepts and logical relationships in replicate-based experimental design.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Pseudoreplication

What is the problem? Pseudoreplication occurs when data points are not statistically independent but are treated as independent observations in an analysis. This artificially inflates your sample size and invalidates statistical tests [8] [9].

How to diagnose it: Ask these questions about your experimental design:

- Q1: What is the smallest unit to which my treatment is independently applied? This is your true experimental unit [9].

- Q2: Are my "replicates" actually multiple measurements from the same experimental unit? If yes, these are repeated measures or pseudoreplicates, not true replicates [8] [10].

- Q3: Could measurements within a group be more similar to each other due to a shared source? This hierarchical structure (e.g., cells within an animal, plants within a plot) indicates potential pseudoreplication [10].

Table: Identifying Experimental Units and Pseudoreplicates

| Experimental Scenario | True Experimental Unit | Common Pseudoreplicate | Why It's a Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testing a drug on 5 rats, measuring each 3 times [8] | The rat | The 3 measurements per rat | Measurements from one rat are not independent; analysis must account for the "rat" effect. |

| Growing plants in 2 chambers with different CO₂, 5 plants per chamber [9] | The growth chamber | The individual plants in a chamber | All plants in one chamber share the same environment; treatment effect is confounded with chamber effect. |

| Comparing two curricula in two schools, testing all students [9] | The school | The individual students | Student results are influenced by teacher and school factors; you only have one replicate per treatment. |

| Single-cell RNA-seq from 3 individuals, 100s of cells per individual [10] | The individual person | The individual cells | Cells from the same person share a genetic and environmental background and are not independent. |

How to fix it:

- Design Phase: Ensure your treatment is applied to multiple, independent experimental units [9].

- Analysis Phase: Use statistical models that account for the non-independent structure of your data:

- Mixed-effects models include a random effect for the grouping variable (e.g.,

Rat_ID,Patient_ID,Growth_Chamber) to account for the correlation within groups [10]. - Aggregation methods (e.g., pseudo-bulk) involve averaging the values within each experimental unit first, then performing the analysis on those unit-level means [10].

- Mixed-effects models include a random effect for the grouping variable (e.g.,

The diagram below illustrates the correct way to model data with a hierarchical structure to avoid pseudoreplication.

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Confounding

What is the problem? Confounding occurs when the apparent effect of your treatment of interest is mixed up with the effect of a third, "confounding" variable. This makes it impossible to establish a true cause-and-effect relationship [11] [9].

How to diagnose it: A confounding variable must meet all three of these criteria:

- It is a cause (or a good proxy for a cause) of the outcome.

- It is associated with the treatment or exposure of interest.

- It is not an intermediate step in the causal pathway between the treatment and the outcome [11].

Table: Confounding in Experimental Design

| Scenario | Treatment of Interest | Outcome | Potential Confounder | Why It Confounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational study | Coffee drinking | Lung cancer | Smoking | Smoking causes lung cancer and is associated with coffee drinking. |

| Growth chamber experiment [9] | CO₂ level | Plant growth | Growth chamber | Chamber-specific conditions (light, humidity) affect growth and are perfectly tied to the CO₂ treatment. |

| Drug efficacy study | New Drug vs. Old Drug | Patient recovery | Disease severity | If sicker patients are given the new drug, its effect is confounded by the initial severity. |

How to fix it:

- Randomization: Randomly assign your experimental units to treatment groups. This helps ensure that potential confounders are distributed evenly across groups [11].

- Restriction: Only include subjects within a specific category of the confounder (e.g., only studying 50-60 year-olds to control for age).

- Statistical Control: In your analysis, include the confounding variable as a covariate in a regression model. Caution: Avoid the "Table 2 Fallacy" of interpreting the coefficients of the confounders as causal [11].

Troubleshooting Guide 3: Underpowered Studies

What is the problem? An underpowered study has a sample size that is too small to reliably detect a true effect of the magnitude you are interested in. This leads to imprecise estimates and a high probability of falsely concluding an effect does not exist (Type II error) [11].

How to diagnose it: Your study is likely underpowered if:

- You used a "rule of thumb" for sample size instead of a formal power calculation [11].

- Your confidence intervals for the primary effect are very wide.

- You find a non-significant result (p > 0.05) but the point estimate of the effect is large enough to be scientifically interesting.

Table: Impact of Sample Size and Pseudoreplication on Power and Error

| Condition | Statistical Power | Type I Error (False Positive) Rate | Precision of Effect Size Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate sample size, independent data | Adequate | Properly controlled (e.g., 5%) | Accurate |

| Too few experimental units (Underpowered) | Low | Properly controlled | Low, confidence intervals are wide |

| Pseudoreplication (e.g., analyzing cells, not people) | Inflated (falsely high) | Dramatically inflated [8] [10] [12] | Overly precise, confidence intervals are falsely narrow [8] |

How to fix it:

- A Priori Power Analysis: Before collecting data, conduct a sample size calculation. This requires you to specify:

- The expected effect size (based on pilot data or literature).

- The desired statistical power (typically 80% or 90%).

- The alpha level (typically 0.05).

- Focus on the Experimental Unit: Ensure your power calculation is based on the number of independent experimental units (e.g., the number of animals or human participants), not the number of technical measurements or pseudoreplicates [12].

- Precision Analysis: Alternatively, you can calculate the sample size needed to achieve a desired confidence interval width for your effect estimate.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My field commonly uses "n" to represent the number of cells/technical replicates. Is this pseudoreplication? Yes, this is a very common form of pseudoreplication. The sample size (n) should reflect the number of independent experimental units (e.g., individual animals, human participants, independently treated culture plates) [8] [10]. Measurements nested within these units (cells, technical repeats) are subsamples or pseudoreplicates. Reporting the degrees of freedom (df) for statistical tests can help reveal this error, as the df should be based on the number of independent units [8].

Q2: I have a balanced design with the same number of cells per patient. Can't I just average the values and do a t-test? Yes, this aggregation approach (creating a "pseudo-bulk" value for each patient) is a valid and conservative method to avoid pseudoreplication [10]. However, it can be underpowered, especially if the number of cells per individual is imbalanced. A more powerful and statistically rigorous approach is to use a mixed model with a random effect for the patient, which explicitly models the within-patient correlation [10].

Q3: I corrected for "batch" in my analysis. Does this solve pseudoreplication? No, not necessarily. A standard batch effect correction (like ComBat) is not designed to handle the specific correlation structure of pseudoreplicated data. In fact, simulations have shown that applying batch correction prior to differential expression analysis can further inflate type I error rates [10]. The recommended solution is to use a model with a random effect for the experimental unit (e.g., individual).

Q4: How widespread is the problem of pseudoreplication? Alarmingly common. A 2025 study found that pseudoreplication was present in the majority of rodent-model neuroscience publications examined, and its prevalence has increased over time despite improvements in statistical reporting [12]. An earlier analysis of a single neuroscience journal issue found that 12% of papers had clear pseudoreplication, and a further 36% were suspected of it [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents for Robust Experimental Design

| Tool or Method | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| A Priori Power Analysis | Calculates the required number of independent experimental units to detect a specified effect size, preventing underpowered studies [11]. | Requires an estimate of the expected effect size from pilot data or literature. |

| Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) | Statistical models that properly account for non-independent data (pseudoreplication) by including fixed effects for treatments and random effects for grouping factors (e.g., Individual, Litter) [10]. | Computationally intensive and requires careful model specification. Ideal for single-cell or repeated measures data. |

| Randomization Protocol | A procedure for randomly assigning experimental units to treatment groups to minimize confounding and ensure that other variables are evenly distributed across groups. | The cornerstone of a causal inference study. Does not eliminate confounding but makes it less likely. |

| Blocking | A design technique where experimental units are grouped into blocks (e.g., by age, sex, batch) to control for known sources of variation before random assignment. | Increases precision and power by accounting for a known nuisance variable. |

Defining Your Experimental Unit and Unit of Randomization

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an experimental unit? An experimental unit is the smallest division of experimental material such that any two units can receive different treatments. It is the primary physical entity (a person, an animal, a plot of land, a dish of cells) that is the subject of the experiment and to which a treatment is independently applied [13] [14]. In a study designed to determine the effect of exercise programs on patient cholesterol levels, each patient is an experimental unit [14].

What is a unit of randomization? The unit of randomization is the entity that is randomly assigned to a treatment group. Randomization is the process of allocating these units to the investigational and control arms by chance to prevent systematic differences between groups and to produce comparable groups with respect to both known and unknown factors [15].

Are the experimental unit and the unit of randomization always the same? Not always. The experimental unit is defined by what receives the treatment, while the unit of randomization is defined by how treatments are assigned. While they are often the same entity, in more complex experimental designs, they can differ [16]. The key is that randomization must be applied at the level of the experimental unit, or a level above it, to ensure valid statistical comparisons [17].

What happens if I misidentify the experimental unit? Misidentifying the experimental unit is a critical error that can lead to pseudoreplication—where multiple non-independent measurements are mistakenly treated as independent replicates [17]. This inflates the apparent sample size, invalidates the assumptions of standard statistical tests, and can lead to unreliable conclusions and wasted resources [13] [17].

What are common sources of randomization errors in clinical trials? Several common issues can occur [18] [15]:

- Randomizing an ineligible participant.

- Selecting the wrong stratification group for a participant.

- Randomizing a participant before all eligibility criteria are confirmed.

- A single participant being randomized multiple times.

- Dispensing the incorrect drug kit to a randomized participant.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: I'm unsure how to identify the experimental unit in my study.

Guide: A Step-by-Step Method for Identification Follow this logical process to correctly identify your experimental unit.

Verification Protocol: Once you have a candidate for your experimental unit, ask these questions to verify your choice [19] [17]:

- Question of Independence: Is the treatment applied to this unit independent of the treatment applied to all other units? If the treatment application to one unit potentially affects another, your experimental unit is likely a larger grouping (e.g., the cage of animals, not the individual animal).

- Question of Replication: Does counting this entity give you the true number of independent data points (replicates) for your treatment? If you are taking multiple measurements from the same entity (e.g., three leaf samples from one plant), those are subsamples, not experimental units. The plant itself is the experimental unit.

Real-World Contextual Examples:

- Clinical Trial: Testing a new drug. The experimental unit is the individual patient [14].

- Agriculture: Testing fertilizers. The experimental unit is the plot of land that receives one type of fertilizer, even if you measure multiple plants within that plot.

- Manufacturing: Testing a new menu item in a restaurant chain. The experimental unit is the restaurant, not the individual sandwich or customer, as the intervention is applied at the restaurant level [17].

- Preclinical Animal Study: Testing diet and vitamin supplements. The experimental unit for the diet might be the entire cage of mice (if all mice in a cage eat the same diet), while the experimental unit for the vitamin supplement could be the individual mouse (if each mouse is independently supplemented) [17].

Problem: A randomization error has occurred in my trial.

Guide: Responding to Common Randomization Errors Adhering to the Intention-to-Treat (ITT) principle is crucial when handling errors. The ITT principle states that all randomized participants should be analyzed in their initially randomized group to maintain the balance achieved by randomization and avoid bias [18]. The general recommendation is to document errors thoroughly, not to attempt to "correct" or "undo" them after the fact, as corrections can introduce further issues and bias [18].

The table below summarizes guidance for specific error types based on established clinical trial practice [18].

| Error Type | Recommended Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ineligible Participant Randomized | Keep the participant in the trial; collect all data. Seek clinical input for management. Only exclude if a pre-specified, unbiased process exists. | Maintaining the initial randomization preserves the integrity of the group comparison and prevents selection bias [18]. |

| Participant Randomized with Incorrect Baseline Info | Accept the randomization. Record the correct baseline information in the dataset. | The allocation is preserved for analysis, while accurate baseline data allows for proper characterization of the study population [18]. |

| Multiple Randomizations for One Participant | Scenario A: Only one set of data will be obtained → Retain the first randomization. Scenario B: Multiple data sets will be obtained → Retain both randomizations. | This provides a consistent, unbiased rule that maintains the randomized cohort for analysis [18]. |

| Incorrect Treatment Dispensed | Document the treatment the participant actually received. Seek clinical input regarding their ongoing care. For analysis, the participant remains in their originally randomized group (ITT) but can be excluded from the per-protocol sensitivity analysis [18] [15]. | This documents reality without altering the original randomized group structure, which is essential for the primary analysis [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust Design

| Tool or Reagent | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|

| Interactive Response Technology (IRT) | An automated system (phone or web-based) for managing random assignment of treatments and drug inventory in clinical trials, which helps minimize bias and errors [15]. |

| Stratified Randomization | A technique to ensure treatment groups are balanced with respect to specific, known baseline variables (e.g., disease severity, age group) that strongly influence the outcome [18] [15]. |

| Blocking (Randomized Block Design) | A design principle where experimental units are grouped into "blocks" based on a shared characteristic (e.g., a litter of mice, a batch of reagent). Treatments are then randomized within each block, accounting for a known source of variability [20]. |

| Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Principle | The gold-standard analytical approach where all participants are analyzed in the group to which they were originally randomized, regardless of protocol deviations, errors, or non-compliance. It preserves the benefits of randomization [18]. |

| Experimental Design Assistant (EDA) | A tool to help researchers visually map out the relationships in their experiment, including interventions and experimental units, to ensure clarity and correct structure before the experiment begins [17]. |

Protocol: Implementing a Randomized Block Design

This protocol is essential when a known source of variation (e.g., clinical site, technician, manufacturing batch) could confound your results.

Objective: To control for a nuisance variable by grouping experimental units into homogeneous blocks and randomizing treatments within each block.

Methodology:

- Identify the Blocking Factor: Determine the variable that creates significant, unwanted variation (e.g., "clinical site," "day of the week," "baseline severity score").

- Form Blocks: Group your experimental units into blocks based on this factor. Each block should contain units that are as similar as possible to each other. The number of units per block must be a multiple of the number of treatments.

- Randomize Within Blocks: Independently randomize the assignment of treatments to the experimental units within each block. For example, if you have two treatments (A and B) and a block of 4 units, you would randomly assign 2 units to A and 2 to B within that block.

- Execute Experiment: Apply the treatments and collect data according to the randomized assignment.

- Analyze Data: Use a statistical model (e.g., ANOVA for blocked designs) that includes both the treatment effect and the block effect. This model separates the variation due to the blocking factor from the variation due to the treatment, giving a more precise estimate of the treatment effect.

Troubleshooting Guides

Fundamental Guide: My Experiment Shows No Signal or Effect

Problem: You run your experiment, but the results show no change or signal, even in the experimental group where an effect is expected.

Diagnosis Approach: This problem suggests that your experimental system is not functioning or detecting the phenomenon. Your primary goal is to verify that your test is working correctly.

Solution:

- Implement a Positive Control: Introduce a treatment or sample known to produce a positive result [21] [22]. For example, if testing a new drug, use a known effective drug as a positive control.

- Interpretation:

- If the positive control works: Your experimental system is functional. The lack of effect in your experimental group is likely a true negative result, or your treatment is ineffective at the tested concentration/dose.

- If the positive control fails: Your experimental method, reagents, or equipment are faulty. The problem is with your assay, not necessarily your experimental variable.

Recommended Actions Table:

| Action | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Run a positive control | Verifies the experimental system can detect a positive signal [21]. | In a PCR, use a template known to amplify. |

| Check reagent integrity | Confirms reagents are active and not degraded. | Check expiration dates; prepare fresh solutions. |

| Verify equipment function | Ensures instruments are calibrated and working [21]. | Run a calibration standard on a spectrophotometer. |

| Re-test with a wider concentration range | Rules out that the effect occurs at a different concentration. | Test additional doses of a compound. |

Intermediate Guide: My Negative Control is Showing a Positive Result

Problem: Your negative control, which should not produce an effect, is showing a signal or change. This indicates a potential false positive in your experiment.

Diagnosis Approach: A signal in the negative control suggests that your results are not solely due to your experimental variable. Your goal is to identify and eliminate the source of this contamination or non-specific signal [21] [23].

Solution:

- Systematic Elimination: Investigate common sources of contamination or interference.

- Interpretation: The specific result of your checks will point you toward the root cause.

Troubleshooting Flowchart:

Advanced Guide: My Results Have High, Unexplained Variability

Problem: Your experimental data shows high error bars or significant variability between replicates, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions about the source of variation.

Diagnosis Approach: High variability obscures the true effect of your experimental variable. You must identify and control for the unintended sources of variation (nuisance variables).

Solution:

- Analyze Your Experimental Design: Move away from a One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach, which can miss interactions between factors and is inefficient for finding optimal conditions [24].

- Implement a Designed Experiment (DOE): Use a systematic approach like Design of Experiments (DOE) to efficiently study the effects of multiple factors and their interactions on your response variable [24].

- Review Technical Execution: High variability often stems from inconsistencies in technique, as demonstrated in a cell viability assay where careful pipetting during wash steps was critical to reducing variance [23].

DOE vs. OFAT Comparison Table:

| Aspect | One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Design of Experiments (DOE) |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Low; requires many runs to test multiple factors [24]. | High; tests multiple factors and interactions simultaneously with fewer runs [24]. |

| Interaction Detection | Cannot detect interactions between factors [24]. | Specifically designed to detect and quantify factor interactions [24]. |

| Optimal Setting | Likely misses the true optimum if factor interactions exist [24]. | Uses a model to predict the true optimal settings within the tested region [24]. |

| Best Use Case | Preliminary, exploratory experiments with a single suspected dominant factor. | Systematically understanding complex systems with multiple potential sources of variation [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the difference between a control group and an experimental group? The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable (the treatment or condition you are testing). The control group is identical in every way except it is not exposed to the independent variable. This provides a baseline to compare against, ensuring any observed effect is due to the treatment itself and not other factors [22].

Q2: Why are positive and negative controls necessary if I already have a control group? A control group (or experimental control) provides a baseline for a specific experiment. Positive and negative controls are used to validate the experimental method itself [21] [25].

- A positive control ensures your test can produce a positive result, verifying that all reagents and equipment are working [21] [22].

- A negative control ensures your test does not produce a false positive signal due to contamination or non-specific effects [21] [22]. Together, they confirm the validity and reliability of your results.

Q3: Can a control group also be a positive or negative control? Yes. A single group can serve multiple roles. For example, in a drug trial, the group receiving a standard, commercially available medication is both a control group (for comparison to the new drug) and a positive control (to prove the trial can detect a therapeutic effect) [22].

Implementation and Troubleshooting

Q4: How do I choose the right positive control for my experiment? A valid positive control must be a material or condition known to produce the expected outcome through a well-established mechanism. Examples include [21]:

- A known enzyme activator in an enzyme activity assay.

- A proven antimicrobial agent in a disinfectant test.

- A sample confirmed to contain the target analyte in a diagnostic test.

Q5: My positive control failed. What should I do next? A failed positive control indicates a fundamental problem with your experimental setup. Immediately stop testing and investigate the following:

- Reagent Integrity: Check expiration dates, preparation methods, and storage conditions.

- Equipment Function: Verify that instruments are calibrated, powered on, and functioning correctly [21].

- Protocol Execution: Carefully review the procedure for any errors or deviations.

Q6: How can I formally improve my troubleshooting skills? Troubleshooting is a core scientific skill. Structured approaches, such as the "Pipettes and Problem Solving" method used in graduate training, can be highly effective. This involves [23]:

- Scenario Presentation: A leader presents a detailed experiment with unexpected results.

- Collaborative Dialogue: The group asks specific questions about the experimental setup.

- Consensus Experimentation: The group must agree on a limited number of new experiments to diagnose the problem.

- Result Interpretation: The leader provides mock results, guiding the group to the root cause.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Controlled Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Controls |

|---|---|

| Placebo | An inert substance (e.g., a sugar pill) used as a negative control in clinical or behavioral studies to account for the placebo effect [22]. |

| Known Actives/Agonists | A compound known to activate the target or pathway. Serves as a critical positive control to demonstrate assay capability [22]. |

| Vehicle Control | The solvent (e.g., DMSO, saline) used to deliver the experimental compound. A negative control to ensure the vehicle itself does not cause an effect. |

| Wild-Type Cell Line/Strain | An unmodified biological system used as a control to compare against genetically modified or treated groups, establishing a baseline phenotype. |

| Housekeeping Gene Antibodies | Antibodies against proteins (e.g., GAPDH, Actin) that are constitutively expressed. Used as a loading control in Western blots to ensure equal protein loading across all samples, including controls. |

Experimental Protocol: Vitamin C Detection Assay

Aim: To determine whether a fruit juice contains Vitamin C. Principle: The blue dye DCPIP is decolorized in the presence of Vitamin C.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of the fruit juice in distilled water. In a test tube, add a fixed volume of DCPIP solution.

- Titration: Titrate the fruit juice solution into the DCPIP dropwise, with gentle shaking, until the blue color disappears completely. Record the volume of juice used.

- Control Setup:

- Positive Control: Repeat the titration using a known Vitamin C solution (e.g., ascorbic acid of known concentration). This should successfully decolorize DCPIP, confirming the test is working [21].

- Negative Control: Repeat the titration using distilled water. The blue color of DCPIP should not disappear. Any color change indicates contamination or a faulty reagent [21].

- Interpretation: Compare the volume of juice required to decolorize DCPIP to the volume of the standard Vitamin C solution required to do the same. The negative control validates that the color change is specific to the presence of Vitamin C-like substances.

Systematic Troubleshooting Pathway

The following diagram outlines a generalizable thought process for diagnosing experimental failures, integrating the use of controls and systematic checks.

Strategic Frameworks: DoE and Variance Component Analysis in Practice

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common questions and issues researchers encounter when transitioning from One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) approaches to Design of Experiments (DoE).

Q1: Why should we use DoE instead of the more intuitive OFAT method?

OFAT might seem straightforward, but it has major limitations. It involves changing a single factor while holding all others constant, which fails to capture interactions between factors and can lead to missing the true optimal conditions for your process [26] [24]. In contrast, DoE is a systematic, efficient framework that varies multiple factors simultaneously. This allows you to not only determine individual factor effects but also discover how factors interact, leading to more reliable and complete conclusions with fewer experimental runs [27].

Q2: What are the essential concepts we need to understand to start with DoE?

The key terminology in DoE includes [27]:

- Factor: An input parameter or variable that can be controlled (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration).

- Level: The specific value or setting of a factor during the experiment (e.g., temperature at 100°C and 200°C).

- Response: The output or measured result you are interested in (e.g., yield, purity, strength).

- Effect: The change in the response caused by varying a factor's level.

- Interaction: When the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor.

Q3: Our experiments are often unstable, and the results drift over time. How can DoE help with this?

DoE incorporates fundamental principles to combat such variability and ensure robust results [26]:

- Randomization: Performing experimental runs in a random order helps eliminate the influence of uncontrolled variables and "noise," such as instrument drift or environmental changes.

- Replication: Repeating entire experimental runs allows you to estimate the inherent variability in your process, providing a more reliable measure of factor effects.

- Blocking: When full randomization is impossible (e.g., across different batches of raw material), blocking lets you group similar experimental units to account for this known source of variation.

Q4: We tried a simple 2-factor DoE, but the results were confusing. How do we quantify the effect of each factor?

The effect of a factor is calculated as the average change in the response when the factor moves from its low level to its high level. In a 2-factor design, you can compute this easily [26]. The table below shows data from a glue bond strength experiment.

| Experiment | Temperature | Pressure | Strength (lbs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 100°C | 50 psi | 21 |

| #2 | 100°C | 100 psi | 42 |

| #3 | 200°C | 50 psi | 51 |

| #4 | 200°C | 100 psi | 57 |

- Effect of Temperature: (Strength at High Temp - Strength at Low Temp) =

(51 + 57)/2 - (21 + 42)/2 = 22.5 lbs - Effect of Pressure: (Strength at High Pressure - Strength at Low Pressure) =

(42 + 57)/2 - (21 + 51)/2 = 13.5 lbs[26]

This quantitative analysis clearly shows that temperature has a stronger influence on bond strength under these experimental conditions.

OFAT vs. DoE: A Quantitative Comparison

The following table summarizes the core differences between the OFAT and DoE approaches, highlighting why DoE is superior for understanding complex systems [27].

| Aspect | One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) | Design of Experiments (DoE) |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Inefficient; can require many runs to explore a multi-factor space. | Highly efficient; studies multiple factors simultaneously with fewer runs. |

| Interactions | Cannot detect interactions between factors. | Systematically identifies and quantifies interactions. |

| Optimal Conditions | High risk of finding only sub-optimal conditions. | Reliably identifies true optimal conditions and regions. |

| Statistical Robustness | Does not easily provide measures of uncertainty or significance. | Provides a model with statistical significance for effects. |

| Region of Operation | Cannot establish a region of acceptable results, making it hard to set robust operating tolerances. | Can map a response surface to define a robust operating window. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Basic Two-Level Factorial Design

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for setting up and analyzing a simple yet powerful 2-factor DoE, a foundational design for source of variation analysis.

Pre-Experimental Planning

- Define Objective: Clearly state the goal (e.g., "Maximize the yield of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis").

- Identify Inputs & Outputs: Create a process map. Consult with subject matter experts to select the factors (inputs) to investigate and decide on the response (output) to measure [26]. Use a variable measure (e.g., yield percentage) rather than an attribute (pass/fail) [26].

- Select Factor Levels: For each factor, choose realistic "high" and "low" levels you wish to investigate (e.g., Reaction Temperature: 150°C and 200°C; Catalyst Concentration: 1.0 mol% and 2.0 mol%) [26].

Design Matrix Construction

A full factorial design for k factors requires 2^k runs. For a 2-factor experiment, this means 4 runs. The design matrix can be created using coded values (-1 for low level, +1 for high level) to standardize factors and simplify analysis [26] [27].

| Standard Order | Run Order (Randomized) | Factor A (Temp.) | Factor B (Catalyst) | Response (API Yield %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | -1 (150°C) | -1 (1.0 mol%) | To be measured |

| 2 | 1 | -1 (150°C) | +1 (2.0 mol%) | To be measured |

| 3 | 4 | +1 (200°C) | -1 (1.0 mol%) | To be measured |

| 4 | 2 | +1 (200°C) | +1 (2.0 mol%) | To be measured |

Note: Run order should be randomized to avoid confounding with lurking variables [26].

Execution & Data Collection

- Execute the experiments according to the randomized run order.

- Carefully measure and record the response for each run.

Data Analysis and Model Interpretation

- Calculate Main Effects: Use the method shown in FAQ #4 to quantify the effect of each factor.

- Calculate Interaction Effects: Expand the design matrix to include an interaction column (the mathematical product of the coded levels of Factor A and B). Calculate the interaction effect similarly to the main effects [26].

- Build a Predictive Model: The data can be used to fit a linear model:

Predicted Yield = β₀ + β₁*(Temp) + β₂*(Catalyst) + β₁₂*(Temp*Catalyst). The coefficients (β) are estimated from the data, creating a statistical model that can predict the response across the experimental region [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for a DoE Workflow

While the specific materials depend on the experiment, the following table outlines key conceptual "reagents" and tools essential for a successful DoE.

| Item | Function in DoE Context |

|---|---|

| Coded Factor Levels | Standardizes factors with different units (e.g., °C, mol%, psi) to a common scale (-1, +1), simplifying analysis and comparison of effect magnitudes [27]. |

| Random Number Generator | A tool (software or simple method) to randomize the run order, a critical step for validating the statistical conclusions of the experiment [26]. |

| Design Matrix | The master plan of the experiment. It specifies the exact settings for each factor for every experimental run, ensuring a systematic and efficient data collection process [26] [27]. |

| Statistical Software | Essential for analyzing data from more complex designs, performing significance testing, building predictive models, and creating visualizations like response surface plots [24] [27]. |

DoE Workflow and Interaction Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing a DoE strategy, from planning to optimization, and how it effectively uncovers interactions between factors that OFAT misses.

This technical support guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical troubleshooting guidance for implementing screening designs in experimental research. Screening designs are specialized experimental plans used to identify the few significant factors affecting a process or outcome from a long list of many potential variables [28] [29]. This resource addresses common implementation challenges and provides methodological support for effectively applying these techniques in source of variation analysis.

Understanding Screening Designs

What are Screening Designs and When Should They Be Used?

Screening designs, often called fractional factorial designs, are experimental strategies that systematically identify the most influential factors from many potential variables using a relatively small number of experimental runs [30] [29]. They operate on the "sparsity of effects" principle, which states that typically only a small fraction of potential factors will have significant effects on the response variable [29].

You should consider using screening designs when:

- You have many potential factors to study (typically 5 or more)

- The important factors are unknown among many candidates

- You need to conserve resources by reducing experimental runs

- You are in the early stages of process understanding [30] [28] [29]

These designs are particularly valuable in drug development and manufacturing processes where initial factor spaces can be large, and resource constraints make full factorial experimentation impractical.

How Screening Designs Compare to Other Experimental Approaches

Screening designs differ significantly from full factorial designs in both purpose and execution. The table below summarizes these key differences:

Table: Comparison of Screening Designs and Full Factorial Designs

| Characteristic | Screening Designs | Full Factorial Designs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Identify significant main effects | Characterize all effects and interactions |

| Number of Runs | Efficient, reduced runs | Comprehensive, all combinations |

| Information Obtained | Main effects (some interactions) | All main effects and interactions |

| Resource Requirements | Lower cost and time | Higher cost and time |

| Experimental Stage | Early investigation | Detailed characterization |

| Resolution | Typically III or IV [28] | V or higher |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Screening Design Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for conducting a screening design experiment:

Types of Screening Designs

Several specialized screening designs are available, each with distinct characteristics and applications. The table below compares the most common approaches:

Table: Comparison of Screening Design Types

| Design Type | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Level Fractional Factorial | Estimates main effects while confounding interactions; Resolution III-IV [28] | Initial screening with many factors; Limited runs available | Interactions confounded with main effects |

| Plackett-Burman | Very efficient for many factors; Resolution III [28] | Large factor screens (>10 factors); Minimal runs possible | Assumes interactions negligible |

| Definitive Screening | Estimates main effects, quadratic effects, and two-way interactions | When curvature or interactions suspected; Follow-up studies | Requires more runs than traditional methods [30] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for implementing screening designs in pharmaceutical and biotechnology research:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Experimental Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Process Factors | Variables manipulated during experimentation | Blend time, pressure, pH, temperature, catalyst concentration [29] |

| Response Measurement Tools | Quantify experimental outcomes | Yield determination, impurity analysis, potency assays [29] |

| Center Points | Replicate runs at middle factor levels | Detect curvature, estimate pure error [29] |

| Blocking Factors | Account for systematic variability | Batch differences, operator changes, day effects |

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table: Screening Design Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem/Error | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to Detect Significant Effects | Insufficient power; Too much noise; Factor ranges too narrow | Increase replication; Control noise factors; Widen factor ranges |

| Confounded Effects | Low resolution design; Aliased main effects and interactions | Use higher resolution design; Apply foldover technique to de-alias [30] |

| Curvature Detected in Response | Linear model inadequate; Quadratic effects present | Add axial points for RSM; Use definitive screening design [30] [29] |

| High Experimental Variation | Uncontrolled noise factors; Measurement system variability | Identify and control noise factors; Improve measurement precision |

Resolving Confounding in Screening Designs

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between design resolution and effect confounding, along with potential resolution strategies:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Design Selection and Implementation

What is the minimum number of runs required for a screening design? The minimum run requirement depends on the number of factors and the design type. For a fractional factorial design with k factors, the minimum is typically 2^(k-p) runs, where p determines the fraction. Plackett-Burman designs can screen n-1 factors in n runs, where n is a multiple of 4 [30] [28].

When should I use a Plackett-Burman design versus a fractional factorial design? Use Plackett-Burman designs when you have a very large number of factors (12+) and can assume interactions are negligible. Fractional factorial designs are preferable when you suspect some interactions might be important and you need the ability to estimate them after accounting for main effects [30].

How do I handle categorical factors in screening designs? Most screening designs can accommodate categorical factors by assigning level settings appropriately. For example, a 2-level categorical factor (such as Vendor A/B or Catalyst Type X/Y) can be directly incorporated into the design matrix. For categorical factors with more than 2 levels, specialized design constructions may be necessary [29].

Analysis and Interpretation

How do I interpret the resolution of a screening design? Resolution indicates the degree of confounding in the design. Resolution III designs confound main effects with two-factor interactions. Resolution IV designs confound main effects with three-factor interactions but not with two-factor interactions. Resolution V designs confound two-factor interactions with other two-factor interactions but not with main effects [30] [28].

What should I do if I detect significant curvature in my screening experiment? If center points indicate significant curvature, consider adding axial points to create a response surface design, transitioning to a definitive screening design that can estimate quadratic effects, or narrowing the experimental region to a more linear space [29].

How many center points should I include in my screening design? Typically, 3-5 center points are sufficient for most screening designs. This provides enough degrees of freedom to estimate pure error and test for curvature without excessively increasing the total number of runs [29].

Advanced Applications

Can screening designs be used for mixture components in formulation development? Yes, specialized screening designs exist for mixture components where the factors are proportions of ingredients that must sum to 1. These designs often use simplex designs or special fractional arrangements to efficiently screen many components.

How do I handle multiple responses in screening designs? Analyze each response separately initially, then create overlay plots or desirability functions to identify factor settings that simultaneously satisfy multiple response targets. This is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development where multiple quality attributes must be optimized [29].

What sequential strategies are available if my initial screening design provides unclear results? If results are ambiguous, consider foldover designs to de-alias effects, adding axial points to check for curvature, or conducting a follow-up fractional factorial focusing only on the potentially significant factors identified in the initial screen [30].

Factorial Designs for Analyzing Factor Interactions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of factorial design over testing one factor at a time (OFAT)?

Factorial designs allow you to study the interaction effects between multiple factors simultaneously, which OFAT approaches completely miss [31]. When factors interact, the effect of one factor depends on the level of another. For instance, a specific drug dosage (Factor A) might only be effective when combined with a particular administration frequency (Factor B). A OFAT experiment could lead you to conclude the dosage is ineffective, while a factorial design would reveal this critical interaction [31] [32]. Furthermore, factorial designs are more efficient, providing more information—on multiple factors and their interactions—with fewer resources and experimental runs than conducting multiple separate OFAT experiments [31] [33].

Q2: How do I interpret a significant interaction effect?

A significant interaction effect indicates that the effect of one independent variable on the response is different at different levels of another independent variable [33]. You should not interpret the main effects (the individual effect of each factor) in isolation, as they can be misleading [31].

The best way to interpret an interaction is graphically, using an interaction plot:

- Non-parallel lines suggest an interaction is present [34] [35].

- Crossing lines indicate a strong interaction, where the effect of one factor completely reverses depending on the level of the other factor [35].

For example, in a plant growth study, the effect of a fertilizer (Factor A) might be positive at high sunlight (Factor B) but negative at low sunlight. The interaction plot would show non-parallel lines, and the analysis would reveal a significant interaction term [35].

Q3: My experiment has many potential factors. How can I manage the number of experimental runs?

With a full factorial design, the number of runs grows exponentially with each additional factor (2^k for a 2-level design with k factors) [36]. To manage this, researchers use screening designs:

- Fractional Factorial Designs: These use a carefully chosen subset (a fraction) of the full factorial runs. This allows you to efficiently screen many factors to identify the few that are most important, though some higher-order interactions may be confounded with main effects [37] [38].

- Definitive Screening Designs (DSDs): These are advanced, highly efficient designs that allow for screening a large number of factors with a minimal number of runs and can detect curvature in the response [38].

The key is to use these screening designs early in your experimentation process to narrow down the field of factors before conducting a more detailed full or larger fractional factorial study on the critical few [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: The experimental error is too high, obscuring factor effects.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive variability in raw materials or process equipment. | Review records of raw material batches and equipment calibration. Check control charts for the process if available. | Implement stricter material qualification. Use blocking in your experimental design to account for known sources of variation like different batches or machine operators [37] [36]. |

| Uncontrolled environmental conditions. | Monitor environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity) during experiments to see if they correlate with high-variability runs. | Control environmental factors if possible. Otherwise, use blocking to group experiments done under similar conditions [36]. |

| Measurement system variability. | Conduct a Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility (Gage R&R) study. | Improve measurement procedures. Calibrate equipment more frequently. Increase the number of replications for each experimental run to get a better estimate of pure error [36]. |

Problem 2: The analysis shows no significant main effects or interactions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Factor levels were set too close together. | Compare the range of your factor levels to the typical operating range or known process variability. The effect of the change might be smaller than the background noise. | Increase the distance between the high and low levels of your factors to evoke a stronger, more detectable response, provided it remains within a safe and realistic range [38]. |

| Insufficient power to detect effects. | Check the number of experimental runs and replications. A very small experiment has a high risk of Type II error (missing a real effect). | Increase the sample size or number of replications. Use power analysis before running the experiment to determine the necessary sample size [32]. |

| Important factors are missing from the design. | Perform a cause-and-effect analysis (e.g., Fishbone diagram, FMEA) to identify other potential influencing variables. | Conduct further screening experiments with a broader set of potential factors based on process knowledge and brainstorming [38]. |

Problem 3: The regression model has poor predictive ability.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| The relationship between a factor and the response is curved (non-linear). | Check residual plots from your analysis for a clear pattern (e.g., a U-shape). A 2-level design can only model linear effects. | Move from a 2-level factorial to a 3-level design or a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like a Central Composite Design, which can model curvature (quadratic effects) [36]. |

| The model is missing important interaction terms. | Ensure your statistical model includes all potential interaction terms and that the ANOVA or regression analysis tests for their significance. | Re-analyze the data, explicitly including interaction terms in the model. A factorial design is orthogonally capable of estimating these interactions [31] [37]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Basic 2x2 Factorial Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps for designing a simple two-factor, two-level factorial experiment [31] [35].

- Define the Objective: Clearly state the research question and the response variable you are measuring.

- Select Factors and Levels: Choose two factors (e.g., Temperature, Concentration). For each, define a "low" and "high" level (e.g., 50°C and 70°C; 1% and 2%). These levels should be sufficiently different to expect a measurable change in the response.

- Create the Experimental Matrix: This lists all possible combinations of the factor levels. For a 2x2 design, this results in 4 unique experimental conditions.

- Randomize the Run Order: Randomly assign the order in which you will perform the four experimental runs. This is critical to avoid confounding the factor effects with unknown lurking variables or time-based trends [31] [36].

- Execute Experiments and Collect Data: Carry out the experiments in the randomized order, carefully measuring the response variable for each run.

- Analyze the Data: Calculate the main effects and the interaction effect. This can be done using statistical software that performs ANOVA or regression analysis.

Table: Experimental Matrix for a 2x2 Factorial Design

| Standard Run Order | Randomized Run Order | Temperature | Concentration | Response (e.g., Yield) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Low (50°C) | Low (1%) | |

| 2 | 1 | High (70°C) | Low (1%) | |

| 3 | 4 | Low (50°C) | High (2%) | |

| 4 | 2 | High (70°C) | High (2%) |

Protocol 2: Calculating Main and Interaction Effects

This protocol provides the mathematical methodology for calculating effects from a 2x2 factorial experiment, which forms the basis for the statistical model [35].

The regression model for a 2-factor design with interaction is: y = β₀ + β₁x₁ + β₂x₂ + β₁₂x₁x₂ + ε [37] Where y is the response, β₀ is the intercept, β₁ and β₂ are the main effect coefficients, β₁₂ is the interaction coefficient, and ε is the random error.

The calculations for a 2x2 design can be done using the average responses at different factor levels:

- Main Effect of Factor A: (Average response at Ahigh) - (Average response at Alow)

- Main Effect of Factor B: (Average response at Bhigh) - (Average response at Blow)

- Interaction Effect AB: (Average response when A and B are at the same level) - (Average response when A and B are at different levels). More precisely, it is half the difference between the effect of A at high B and the effect of A at low B [35].

Table: Calculation of Effects from Experimental Data

| Factor A | Factor B | Response | Calculation Step | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 2 | Main Effect A = (9+5)/2 - (2+0)/2 | 6 |

| High | Low | 5 | Main Effect B = (2+9)/2 - (5+0)/2 | 3 |

| Low | High | 9 | Interaction AB = ( (9-2) - (5-0) ) / 2 | 1 |

| High | High | 9 |

Experimental Workflows and Relationships

Factorial Experiment Workflow

Visualizing Interaction Effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Factorial Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Minitab, etc.) | Used to randomize run order, create the experimental design matrix, and perform the statistical analysis (ANOVA, regression). | The FrF2 package in R can generate and analyze fractional factorial designs [37]. |

| Coding System (-1, +1) | A method for labeling the low and high levels of factors. Simplifies the design setup, calculation of effects, and fitting of regression models [35]. | A temperature factor with levels 50°C and 70°C would be coded as -1 and +1, respectively. |

| Random Number Generator | A tool (often part of software) to ensure the run order of experimental trials is randomized. This is a critical principle of DOE to avoid bias [31] [36]. | Used to create the "Randomized Run Order" column in the experimental matrix. |

| Blocking Factor | A variable included in the design to account for a known, nuisance source of variation (e.g., different days, raw material batches). It is not of primary interest but helps reduce experimental error [37] [36]. | If experiments must be run on two different days, "Day" would be included as a blocking factor to prevent day-to-day variation from obscuring the effects of the primary factors. |

| ANOVA Table | The primary statistical output used to determine the significance of the main and interaction effects by partitioning the total variability in the data [36] [33]. | The p-values in the ANOVA table indicate whether the observed effects are statistically significant (typically p < 0.05). |

Step-by-Step Guide to Variance Component Analysis

Variance Component Analysis (VCA) is a statistical technique used in experimental design to quantify and partition the total variability in a dataset into components attributable to different random sources of variation [39]. This method is particularly valuable for researchers and scientists in drug development who need to understand which factors in their experiments contribute most to overall variability, enabling more precise measurements and better study designs.

Within the broader thesis on experimental design for source of variation research, VCA provides a mathematical framework for making inferences about population characteristics beyond the specific levels studied in an experiment. This approach helps distinguish between fixed effects (specific, selected conditions) and random effects (factors representing a larger population of possible conditions) [40].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Variance components are estimates of the part of total variability accounted for by each specified random source of variability [39]. In a nested experimental design, these components represent the hierarchical structure of data collection.

The mathematical foundation of VCA relies on linear mixed models where the total variance (σ²total) is partitioned into independent components. For a simple one-way random effects model, this can be represented as: σ²total = σ²between + σ²within, where σ²between represents variability between groups and σ²within represents variability within groups [41].

Distinction between fixed and random effects is crucial: fixed effects refer to specific, selected factors where levels are of direct interest, while random effects represent factors where levels are randomly sampled from a larger population, with the goal of making inferences about that population [40].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Basic Protocol for One-Way Random Effects Model

For researchers conducting initial VCA, the following step-by-step protocol provides a robust methodology:

Experimental Design Phase: Identify all potential sources of variation in your study. Determine which factors are fixed versus random effects. Ensure appropriate sample sizes for each level of nesting.

Data Collection: Collect data according to the hierarchical structure of your design. For example, in an assay validation study, this might include multiple replicates within runs, multiple runs within days, and multiple days within operators.

Model Specification: Formulate the appropriate linear mixed model. For a one-way random effects model: Yij = μ + αi + εij, where αi ~ N(0, σ²α) represents the random effect and εij ~ N(0, σ²_ε) represents residual error.

Parameter Estimation: Use appropriate statistical methods to estimate variance components. The ANOVA method equates mean squares to their expected values: σ²α = (MSbetween - MSwithin)/n and σ²ε = MS_within.

Interpretation: Express components as percentages of total variance to understand their relative importance.

Advanced Protocol for Complex Designs

For more complex experimental designs common in pharmaceutical research:

Handling Unbalanced Designs: Most real-world designs are unbalanced. Use restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation rather than traditional ANOVA methods for more accurate estimates [40].

Addressing Non-Normal Data: For non-normal data (counts, proportions), consider generalized linear mixed models or specialized estimation methods for discrete data [40].

Accounting for Spatial/Temporal Correlation: Incorporate appropriate correlation structures when data exhibit spatial or temporal dependencies to avoid misleading variance component estimates [40].

Incorporating Sampling Weights: For complex survey designs with nonproportional sampling, use sampling weights to ensure representative variance component estimates [40].

VCA Methodology Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Negative Variance Estimates

Problem: Statistical software returns negative estimates for variance components, which is theoretically impossible since variances cannot be negative.

Causes:

- Insufficient sample size: Too few levels of the random factor or too few replicates [42]

- Outliers: Extreme values that distort variance patterns [42]

- True variance is zero: The random effect may not actually contribute to variability [42]

- Unbalanced designs: Highly unequal group sizes can lead to estimation problems [42]

- Incorrect model specification: The assumed covariance structure may not match the data [42]

Solutions:

- Increase sample size: Ensure sufficient levels of random factors and adequate replication

- Check for outliers: Examine data for influential points and consider robust estimation methods

- Use bounded estimation: Apply methods that constrain estimates to non-negative values [43]

- Try different estimation methods: Use REML instead of ANOVA methods, or Bayesian approaches with proper priors

- Simplify the model: Remove unnecessary random effects if evidence suggests they contribute little variability

Small Sample Size Issues

Problem: Unreliable variance component estimates due to limited data.

Solutions:

- Use Satterthwaite approximation: For confidence intervals with small samples [39]

- Apply Modified Large Sample (MLS) method: Provides better coverage with small samples [39]

- Consider Bayesian methods: Incorporate prior information to stabilize estimates

Handling Unbalanced Designs

Problem: Unequal group sizes or missing data leading to biased estimates.

Solutions:

- Use likelihood-based methods: REML provides better estimates for unbalanced data than traditional ANOVA [40]

- Implement appropriate weighting: Use sampling weights for surveys with nonproportional sampling [40]