Grand Challenges and Future Directions in Chemical Biology: A 2025 Perspective on Interdisciplinary Innovation

This article examines the pivotal grand challenges and emerging frontiers in chemical biology as of 2025, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Grand Challenges and Future Directions in Chemical Biology: A 2025 Perspective on Interdisciplinary Innovation

Abstract

This article examines the pivotal grand challenges and emerging frontiers in chemical biology as of 2025, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It synthesizes foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodological applications, critical optimization strategies, and robust validation frameworks that define the field. By exploring themes from bio-orthogonal chemistry and AI-driven discovery to translational physiology and sustainability, the content provides a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging chemical principles to solve complex biological problems and accelerate therapeutic innovation.

Defining the Frontier: Core Concepts and Exploratory Visions in Modern Chemical Biology

Chemical biology is a scientific discipline that resides at the interface between chemistry and biology, characterized by its application of chemical techniques, analysis, and often small molecules produced through synthetic chemistry to the study and manipulation of biological systems [1]. Unlike biochemistry, which primarily concerns itself with the chemistry of biomolecules and regulation of biochemical pathways within and between cells, chemical biology distinguishes itself through its focused application of chemical tools to address fundamental biological questions [1]. This philosophical approach transforms biological complexity into manageable chemical problems, creating a multidisciplinary nexus that has become essential for modern scientific advancement.

The field has undergone significant conceptual evolution, expanding from early chemical investigations of biological compounds to an integrated organizational platform that optimizes drug target identification and validation while improving the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [2]. This evolution represents more than merely technical progress—it embodies a fundamental shift in how scientists conceptualize the relationship between chemical structure and biological function. The chemical biology platform achieves its goals through emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes and leveraging knowledge gained from the action of similar molecules on these biological processes, connecting a series of strategic steps to determine whether a newly developed compound could translate into clinical benefit using translational physiology [2].

Historical Evolution: From Foundational Discoveries to a Distinct Discipline

The conceptual roots of chemical biology extend deep into the history of science, though it is often considered a relatively new scientific field [1]. The term itself can be traced to early appearances in scientific literature, including Alonzo E. Taylor's 1907 book "On Fermentation" and John B. Leathes' 1930 article "The Harveian Oration on The Birth of Chemical Biology" [1]. Despite these early references, the philosophical underpinnings of chemical biology predate even this terminology, evident in transformative 19th century discoveries that bridged chemical and biological realms.

Friedrich Wöhler's 1828 synthesis of urea represents a pivotal moment in the prehistory of chemical biology, demonstrating that biological compounds could be synthesized with inorganic starting materials and effectively weakening the previously dominant notion of vitalism—the theory that a 'living' source was required to produce organic compounds [1]. This fundamental discovery showed that the principles of chemistry could recreate molecules previously thought to be exclusively products of biological systems, thereby erasing the absolute boundary between organic and inorganic compounds and establishing a philosophical foundation for interrogating biological systems through chemical methods.

The late 19th century work of Friedrich Miescher further advanced this integrative approach. His investigation of the cellular contents of human leukocytes led to the discovery of 'nuclein' (later renamed DNA) [1]. By isolating nuclein from leukocyte nuclei through protease digestion and applying chemical techniques such as elemental analysis and solubility tests to determine its composition, Miescher established a methodology that would lay the groundwork for Watson and Crick's seminal discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA [1]. This approach exemplified the core chemical biology philosophy: using chemical tools to elucidate biological structures and functions.

Table: Historical Foundations of Chemical Biology

| Time Period | Key Figure | Contribution | Impact on Chemical Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1828 | Friedrich Wöhler | Synthesis of urea from inorganic compounds | Weakened vitalism; established that biological compounds could be studied synthetically |

| Late 19th century | Friedrich Miescher | Discovery and chemical characterization of 'nuclein' (DNA) | Demonstrated application of chemical analysis to biological macromolecules |

| 1907 | Alonzo E. Taylor | Used term "chemical biology" in "On Fermentation" | Early formalization of the disciplinary concept |

| 1930 | John B. Leathes | "The Harveian Oration on The Birth of Chemical Biology" | Further conceptual development of the field |

| 2000s | Various | Establishment of dedicated journals | Institutional recognition as distinct discipline |

The rising prominence of chemical biology as a distinct discipline is reflected in the establishment of dedicated scientific journals in the 21st century, including Nature Chemical Biology (created in 2005) and ACS Chemical Biology (created in 2006) [1]. These publications provided dedicated venues for research that explicitly bridged chemical and biological domains, further solidifying the field's identity and methodological approaches.

Methodological Framework: The Chemical Biology Toolkit

The practice of modern chemical biology relies on a sophisticated methodological framework that integrates techniques from both chemistry and biology. This toolkit continues to evolve through technical innovations that expand our ability to probe and manipulate biological systems.

Synthetic and Analytical Approaches

Chemical biology employs diverse synthetic and analytical strategies to investigate biological systems. Peptide synthesis represents a cornerstone methodology, enabling the chemical synthesis of proteins that incorporate non-natural amino acids and residue-specific incorporation of "posttranslational modifications" such as phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation, and even ubiquitination [1]. These capabilities are invaluable for probing and altering protein functionality, as post-translational modifications are widely known to regulate protein structure and activity [1]. To assemble protein-sized polypeptide chains from small synthetic peptide fragments, chemical biologists employ native chemical ligation, a process involving the coupling of a C-terminal thioester and an N-terminal cysteine residue, ultimately resulting in formation of a "native" amide bond [1]. Related strategies include expressed protein ligation, sulfurization/desulfurization techniques, and use of removable thiol auxiliaries [1].

Combinatorial chemistry provides another essential methodology, involving the simultaneous synthesis of large numbers of related compounds for high-throughput analysis [1]. Chemical biologists apply principles from combinatorial chemistry to synthesize active drug compounds and maximize screening efficiency, with applications extending to agriculture and food research, specifically in the syntheses of unnatural products and generating novel enzyme inhibitors [1].

Bioorthogonal reactions represent a particularly powerful chemical biology approach that enables selective chemical reactions within complex biological environments. These reactions must proceed with high chemospecificity despite the milieu of distracting reactive materials in vivo, and within reasonably short timeframes [1]. Click chemistry is well suited to this niche, with its rapid, spontaneous, selective, and high-yielding characteristics [1]. The development of copper-free variants, such as cyclooctyne reactions with azido-molecules, bypassed toxicity issues associated with copper catalysts, enabling applications in living systems [1].

Table: Core Methodologies in Chemical Biology

| Methodology | Key Principle | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide Synthesis & Native Chemical Ligation | Chemical production of proteins with non-natural amino acids or post-translational modifications | Protein engineering, functional probing, structure-activity studies |

| Combinatorial Chemistry | Simultaneous synthesis of large compound libraries | High-throughput screening, drug discovery, enzyme inhibitor development |

| Bioorthogonal Chemistry | Selective chemical reactions compatible with living systems | Biomolecule labeling, imaging, tracking in cellular environments |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling | Using chemical probes that target enzymatically active forms | Functional proteomics, enzyme activity monitoring, inhibitor development |

| Directed Evolution | Laboratory-based evolution of biomolecules with desired traits | Enzyme engineering, protein optimization, catalyst development |

Omics and Systems Approaches

Chemical biology has increasingly embraced systems-level approaches, particularly through various "omics" methodologies that provide comprehensive analysis of biological systems. These include advanced high-throughput analytical approaches designed to handle complex mixtures of cell-derived biomolecules, providing both quantitative and qualitative information about biological systems [3]. Chemical biologists work to improve proteomics through the development of enrichment strategies, chemical affinity tags, and new probes [1]. Given that samples for proteomics often contain many peptide sequences with varying abundance, chemical biology methods reduce sample complexity by selective enrichment using affinity chromatography—targeting peptides with distinguishing features like biotin labels or post-translational modifications [1].

For investigating enzymatic activity specifically (as opposed to total protein abundance), activity-based reagents have been developed to label the enzymatically active form of proteins [1]. This strategy includes converting serine hydrolase- and cysteine protease-inhibitors to suicide inhibitors, enhancing the ability to selectively analyze low abundance constituents through direct targeting [1]. Enzyme activity can also be monitored through converted substrate, with methods using "analog-sensitive" kinases to label substrates using an unnatural ATP analog, facilitating visualization and identification through a unique handle [1].

Directed Evolution and Protein Engineering

A primary goal of protein engineering is the design of novel peptides or proteins with a desired structure and chemical activity [1]. Since knowledge of the relationship between primary sequence, structure, and function of proteins remains limited, rational design of new proteins with engineered activities is extremely challenging [1]. Directed evolution addresses this challenge through repeated cycles of genetic diversification followed by a screening or selection process, effectively mimicking natural selection in the laboratory to design new proteins with desired activity [1].

Methods for creating large libraries of sequence variants include subjecting DNA to UV radiation or chemical mutagens, error-prone PCR, degenerate codons, or recombination [1]. Once variant libraries are created, selection or screening techniques such as FACS, mRNA display, phage display, and in vitro compartmentalization are used to identify mutants with desired attributes [1]. The development of directed evolution methods was recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Frances Arnold for evolution of enzymes, and George Smith and Gregory Winter for phage display [1].

Translational Applications: From Bench to Bedside

The chemical biology platform has proven particularly valuable in translational applications, especially pharmaceutical research and development. The last 25 years of the 20th century marked a pivotal period where pharmaceutical companies began producing highly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms but faced significant challenges in demonstrating clinical benefit [2]. This challenge prompted transformative changes in drug development, leading to the emergence of translational physiology and precision medicine, aided fundamentally by the development of the chemical biology platform [2].

The Chemical Biology Platform in Drug Development

Chemical biology refers to the study and modulation of biological systems, and the creation of biological response profiles using small molecules that are often selected or designed based on current knowledge of the structure, function, or physiology of biological targets [2]. Unlike traditional trial-and-error approaches, even when using high throughput technologies, chemical biology focuses on selecting target families and incorporates systems biology approaches to understand how protein networks integrate [2]. The main advantage of incorporating a chemical biology platform into therapeutic development strategies is its use of multidisciplinary teams to accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to accelerate timelines and reduce costs for bringing new drugs to patients [2].

The implementation of this platform approach involved several historical steps. The first was bridging disciplines between chemists and pharmacologists, who previously worked in relative isolation [2]. The second step introduced clinical biology to bridge relationships and foster teamwork, encouraging collaboration among preclinical physiologists and pharmacologists and clinical pharmacologists [2]. Clinical biology referred to the use of laboratory assessments (later termed biomarkers) to diagnose disease, evaluate patient health, and monitor treatment efficacy [2]. The third step was the formal development of chemical biology platforms around 2000 to take advantage of genomics information, combinatorial chemistry, improvements in structural biology, high throughput screening, and various cellular assays [2].

Assessment of Chemical Probes

A critical application of chemical biology in drug discovery is the objective, quantitative, data-driven assessment of chemical probes [4] [5]. These chemical probes are essential tools for understanding biological systems and for target validation, yet selecting probes for biomedical research has rarely been based on objective assessment of all potential compounds [5]. Resources such as Probe Miner capitalize on public medicinal chemistry data to empower quantitative, objective, data-driven evaluation of chemical probes, assessing >1.8 million compounds for their suitability as chemical tools against 2,220 human targets [5]. This approach represents a valuable resource to aid the identification of potential chemical probes, particularly when used alongside expert curation [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents in Chemical Biology

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Probes | Modulate and monitor biological systems | Protein function inhibition, cellular process tracking [1] |

| Bioorthogonal Reporters (e.g., azides, cyclooctynes) | Selective chemical labeling in living systems | Biomolecule imaging, tracking, and characterization [1] |

| Unnatural Amino Acids | Expand genetic code and protein functionality | Protein engineering, structure-function studies [3] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Target enzymatically active forms of proteins | Functional proteomics, enzyme mechanism studies [1] |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Induce targeted protein degradation | Therapeutic development, protein function analysis [1] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Components | Precision gene editing | Functional genomics, gene therapy development [1] |

Current Trends and Future Directions

Chemical biology continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. The field is poised to have a profound impact across various domains, including precision medicine, synthetic biology, and agricultural biotechnology [6]. Current trends include advances in chemical synthesis, single-cell analysis techniques, and computational methods, all of which are driving new discoveries and applications [6].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The unprecedented boom in artificial intelligence and machine learning applications represents a significant frontier in chemical biology [7]. These computational approaches are being applied to multiple aspects of the field, from compound screening and design to pattern recognition in complex biological data sets. The 2025 Gordon Research Conference on Chemical and Biological Defense highlights the growing importance of these methodologies, with dedicated sessions on "AI/ML for Chemical and Biological Defense: Emerging Technologies" and "AI/ML for Chemical and Biological Defense: Global Applications" [7]. However, important questions regarding reliable, reproducible, and safe use of such methods remain and form the chassis for ongoing discussions in the field [7].

Agnostic Detection and Characterization Methods

A prominent trend in applied chemical biology involves the development of broad-spectrum methods for agnostic chemical and biological detection [7]. This approach focuses on creating capabilities to identify, characterize, and diagnose novel threats or biological phenomena without prior knowledge of their specific characteristics. The 2025 GRC conference emphasizes "agnostic solutions for characterizing and mitigating chemical and biological threats," highlighting technologies for diagnostics of novel chemical and biological agents [7]. These methodologies represent a shift from targeted approaches to more flexible, adaptable systems that can respond to emerging challenges.

Advanced Biomanufacturing and Therapeutic Modalities

Biomanufacturing readiness represents another significant frontier, encompassing the journey from design to deployment of biologically-based solutions [7]. This includes developing capabilities for rapid production of therapeutics, vaccines, and diagnostic tools, as highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic response [3]. The campaign to develop and distribute SARS-CoV-2 vaccines demonstrated the power of concentrated scientific effort, requiring complex steps from conception of viable methodological approaches to overcoming social and legal hurdles and establishing large-scale production and distribution methods [3]. This achievement stands as a testament to applied chemical biology principles, requiring collaboration across scientific disciplines and geographic boundaries.

Additional emerging therapeutic approaches include wearable-based advancements for chemical-biological threats and novel solutions to counter emerging chem-bio threats through vaccines, therapeutics, and other modalities [7]. The ARPA-H model represents one approach to advancing these technologies, focusing on high-risk transformative research on disease-agnostic technologies to pursue better health outcomes [7].

Chemical biology has evolved from a conceptual interface between established disciplines to a mature scientific field with its own distinctive philosophical approach, methodological toolkit, and research agenda. Its practitioners are life scientists who embrace interdisciplinary research and techniques, not limited by the constraints of target biological systems but constantly seeking to expand and overcome those limitations by exploring new territories within science [3]. The field's trajectory demonstrates how artificial disciplinary boundaries can be transcended to create integrated approaches that address complex biological problems through chemical principles.

The future of chemical biology will likely be characterized by continued methodological innovation, particularly in areas of synthetic chemistry, single-cell analysis, computational integration, and therapeutic development. As the field addresses its grand challenges—including ethical considerations, interdisciplinary collaboration, and funding—its continued impact across multiple domains seems assured [6]. Realizing the full potential of chemical biology will require ongoing investment in research, education, and infrastructure, ensuring that the next generation of researchers is equipped with both the technical skills and interdisciplinary mindset needed to advance this dynamic field [2] [6]. Through these developments, chemical biology will continue to refine its multidisciplinary philosophy, remaining a critical component of modern scientific inquiry and therapeutic advancement.

Chemical biology represents a powerful interdisciplinary frontier where the tools and principles of chemistry are deployed to interrogate, manipulate, and understand biological systems. This field leverages synthetic chemistry to create molecular probes, modulate biological pathways, and mimic natural processes, thereby bridging the gap between the test tube and the living cell. The grand challenge lies in mastering bio-inspired synthesis—developing chemical methods that emulate the efficiency and selectivity of biological systems—and applying these capabilities to the fundamental task of understanding living systems [8]. This whitepaper outlines the central challenges and future directions defining this rapidly evolving discipline, framed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The core premise of modern chemical biology is that living systems perform chemical transformations with a precision and under conditions that conventional synthetic chemistry often cannot replicate [8]. This recognition has driven the field increasingly toward bioinspired and bio-integrated strategies, including biocatalysis, chemoenzymatic cascades, and bio-orthogonal chemistry. Each of these approaches relies heavily on organic chemical synthesis, which provides the foundational capability to construct and modify molecules that can probe, modulate, or mimic biological functions [8]. The following sections dissect the key research areas, present quantitative data, provide detailed methodologies, and visualize the conceptual frameworks that underpin the field's trajectory.

Grand Challenge 1: Mastering Bio-inspired Synthetic Strategies

Biomimetic Synthesis and Catalysis

Biomimetic reactions are chemical processes designed to mimic the strategies and efficiencies found in nature, particularly those catalyzed by enzymes. The objective is to study how nature achieves specific reactions and then apply those principles to create more efficient and selective synthetic pathways [8]. This approach aligns strongly with Green Chemistry goals, emphasizing solvent safety, atom economy, and waste minimization [8]. However, significant obstacles persist in designing biomimetic reactions, including technical difficulties in controlling stereoselectivity, achieving high yields, and addressing scalability issues for industrial production [8]. Furthermore, the frequent use of expensive or environmentally hazardous reagents complicates the translation of natural systems into practical laboratory protocols.

A prominent application of biomimetic synthesis is the production of natural products, which serve as a rich source of complex bioactive structures [8]. A major challenge in translating natural products into viable medicines is the difficulty in acquiring adequate amounts of the original compounds and their structural variants to support research and large-scale manufacturing. To address supply chain vulnerabilities and sustainability concerns, researchers pursue synthetic strategies that ensure a reliable supply of these valuable compounds, with organic synthesis remaining essential for functional diversification and analog generation beyond the scope of biosynthesis [8].

Biocatalysis and Enzyme Engineering

Biocatalysis utilizes biological catalysts—primarily enzymes or whole cells—to promote chemical reactions. Natural enzymes offer tremendous advantages by catalyzing reactions with high selectivity under mild, environmentally benign conditions [8]. The field was notably advanced by Frances Arnold's Nobel Prize-winning work on directed evolution of enzymes, a technique that applies evolutionary principles (random gene mutation and natural selection) to engineer improved enzymatic performance [8]. This methodology has yielded new biocatalysts, products, and processes for pharmaceuticals and renewable fuels.

Despite these advances, extending enzyme utility to non-natural substrates and reactions such as C-H activation or oxidative coupling remains challenging [8]. Mimicking these transformations with synthetic catalysts, including organocatalysts or artificial metalloenzymes, also presents obstacles in selectivity, scalability, and green chemistry compatibility. Recent innovations include biocatalytic amide bond formation, use of hydrolases and ATP-dependent enzymes in nonaqueous systems, and integration of enzymes into multi-step synthetic cascades [8]. Enzyme engineering through side-chain derivatization or introduction of non-canonical amino acids continues to expand the repertoire of accessible reactions [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Catalytic Strategies in Chemical Biology

| Catalytic Strategy | Key Advantage | Primary Challenge | Emerging Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Organic Synthesis | Broad reaction scope, well-established | Harsh conditions, poor selectivity | Development of milder, selective catalysts |

| Biocatalysis (Wild-type Enzymes) | High selectivity, green conditions | Limited substrate scope | Directed evolution [8] |

| Biomimetic Catalysis | Principles from efficient natural systems | Reproducing active site complexity | Sophisticated ligand design |

| Photobiocatalysis | Access to excited state reactivity | Integration of biological and photochemical steps | Co-factor engineering [8] |

Chemoenzymatic and Photobiocatalytic Approaches

The field has recently witnessed a rapid rise in chemoenzymatic strategies that combine enzymatic and chemical steps in a complementary fashion [8]. This hybrid approach installs complexity via enzymes and then elaborates structures via synthetic chemistry, or vice versa, allowing for the generation of analogues with modified scaffolds that are inaccessible through biosynthesis alone. A particularly innovative development is the emergence of photobiocatalytic strategies for organic synthesis, which involve enzymatic processes that utilize electronically excited states accessed through photoexcitation [8].

These hybrid strategies, while powerful, demand careful coordination of solvents, protective groups, and reaction conditions. Significant challenges include pathway optimization, enzyme engineering, and coupling biosynthetic routes with chemical transformations to produce novel compounds [8]. The successful implementation of these integrated approaches requires deep expertise in both chemical and biological domains, presenting a training challenge for the next generation of chemical biologists.

Grand Challenge 2: Developing Bio-orthogonal Chemistry for Living Systems

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Bioorthogonal chemistry refers to chemical reactions that can occur within a living organism without interfering with its native biochemical processes [8]. Within this domain, click reactions represent a special class defined by stringent criteria including modularity, broad scope, high yield, stereospecificity, and generation of harmless by-products [8]. The profound significance of bioorthogonal chemistry was recognized with the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to C. R. Bertozzi, M. Meldal, and K. B. Sharpless for their foundational contributions. These reactions are critical for applications in in vivo imaging, drug delivery, and prodrug activation [8].

Organic synthesis is central to designing bioorthogonal reagents with fast kinetics, minimal toxicity, and excellent functional group tolerance under physiological conditions. Recent developments have focused on advancing tetrazine ligations, employing strained alkynes, and creating light-activated or redox-triggered reactions [8]. The continuous refinement of these chemical tools expands the toolbox available for interrogating biological systems with minimal perturbation.

The Translational Hurdle: From In Vitro to In Vivo

The most significant challenge in bioorthogonal chemistry is the translation from model systems to living organisms, particularly humans for clinical applications [8]. Performing a reaction in a controlled laboratory environment differs dramatically from delivering that same reaction in a complex living patient. Success in vivo demands high reactivity to achieve sufficient yields at medically relevant concentrations within the available reaction time. Furthermore, reagents with limited stability or circulation time must react rapidly enough to elicit the desired biological effect before being cleared or metabolized [8].

Multiple pharmacological factors determine the success of bioorthogonal reactions in vivo. Pharmacokinetic properties of both reagents dictate their in vivo behavior through processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [8]. The stability of the reactants is another crucial consideration, as is their bioavailability—the degree to which components can access the circulation and reach the target area in the body unencumbered [8]. All these factors are intimately dependent on a compound's chemical structure, presenting complex optimization challenges for synthetic chemists.

Table 2: Key Considerations for In Vivo Application of Bio-orthogonal Chemistry

| Factor | Challenge | Impact on Reaction Success |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Kinetics | Must be extremely fast at low concentrations | Determines yield within biological timeframe |

| Reagent Stability | Degradation in physiological environment | Limits effective concentration at target site |

| Pharmacokinetics | Differing distribution/clearance of two reagents | Affects spatiotemporal overlap of reactants |

| Bioavailability | Barriers to reaching target tissue | Reduces effective concentration at site of interest |

| Metabolism | Enzymatic modification of reactants | May deactivate reagents or create off-target effects |

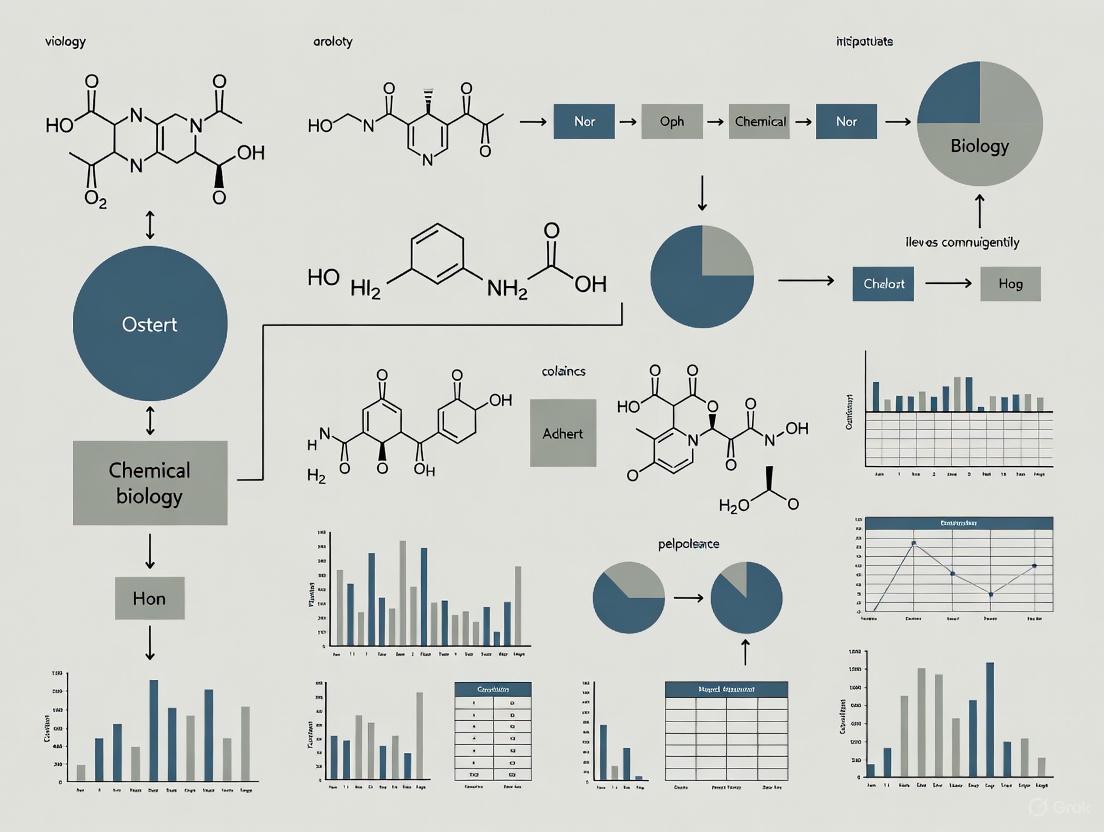

The diagram below illustrates the workflow and major challenges in developing bio-orthogonal reactions for application in living systems.

Quantitative & Analytical Framework for Biological Understanding

Advanced Measurement Techniques

Revolutionary technical advances in measurement science have dramatically enhanced our ability to quantify biological processes. Modern chemical biology leverages sophisticated instrumentation including X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), live imaging, single molecule studies, next-generation sequencing, and mass spectrometry [9]. These technologies generate a wealth of quantitative data for addressing long-standing biological questions, enabling researchers to move from qualitative observations to precise, quantitative measurements of biological phenomena.

The integration of diverse experimental datasets with computational modeling has stimulated productive collaborations across biology, chemistry, physics, and engineering [9]. This interdisciplinary approach requires researchers to possess broad training in both experimental and quantitative skills to perform in-depth mechanistic studies of diverse biological processes. The emerging field of quantitative chemical biology emphasizes the application of mathematical and computational approaches to analyze complex biological systems, creating a more analytical and quantitative framework for understanding life at the molecular level [9].

Standardization and Reproducibility in Experimental Reporting

Robust, reproducible research requires meticulous reporting of experimental details. According to the Royal Society of Chemistry's guidelines, authors must provide sufficient descriptive detail to enable other skilled researchers to accurately reproduce the work [10]. This includes comprehensive characterization of new compounds and known compounds prepared by novel or modified methods. The suggested order for presenting experimental data for new compounds is: yield, melting point, optical rotation, refractive index, elemental analysis, UV absorptions, IR absorptions, NMR spectrum, and mass spectrum [10].

Specific formatting standards ensure clarity and consistency:

- Yield: Should be presented as "the lactone (7.1 g, 56%)" [10]

- Melting point: Should be reported as "mp 75°C (from EtOH)" with crystallization solvent in parentheses [10]

- NMR data: Should use δ values with nucleus indicated by subscript if necessary (e.g., δH, δC). Instrument frequency, solvent, and standard must be specified [10]

- Mass spectrometry: Should be presented as "m/z 183 (M+, 41%), 168 (38)" with relative intensities in parentheses and spectrum type indicated [10]

Adherence to these standards is critical for advancing the field, as inadequate experimental reporting remains a significant barrier to reproducibility and translational progress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in chemical biology requires specialized reagents and materials designed for compatibility with biological systems. The following table details essential components of the chemical biologist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Biology

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-orthogonal Reaction Pairs (e.g., strained alkyne/tetrazine) | Selective labeling in living systems | Fast kinetics, metabolic stability, cell permeability [8] |

| Non-canonical Amino Acids | Incorporation of novel functionality into proteins | Orthogonality to native translation machinery, metabolic handling [8] |

| Chemical Probes (small molecules) | Modulation and study of specific protein functions | Target specificity, potency, minimal off-target effects [8] |

| Caged Compounds | Light-activated control of biological activity | Wavelength compatibility, dark stability, activation efficiency |

| Metabolic Precursors | Feeding biosynthetic pathways for engineered natural products | Membrane permeability, metabolic fate, toxicity [8] |

| Stable Isotope Labels (e.g., ^13C, ^15N) | Tracing metabolic fluxes and structural analysis | Incorporation efficiency, cost, spectral interpretation |

| Directed Evolution Systems | Engineering novel enzyme function | Library diversity, selection throughput, screening method [8] |

Visualization and Data Presentation in Chemical Biology

Color Theory for Scientific Figures

Effective visual communication is essential for conveying complex scientific concepts. The RGB (red, green, blue) additive color model is recommended for figures in digital publications because it mimics how modern displays function [11]. In this model, colors are specified using either numeric triplet notation (e.g., 255, 0, 0 for red) or hexadecimal notation (e.g., #FF0000 for red) [11]. Understanding these specifications ensures accurate color reproduction across different platforms.

Color selection should be guided by established principles to enhance readability and interpretation. A simple strategy employs a single color (e.g., blue) paired with different shades of that color (e.g., navy blue and sky blue) [11]. More complex palettes can be developed using color wheel relationships:

- Complementary colors: Opposite each other on the color wheel [11]

- Analogous colors: Adjacent to each other on the color wheel [11]

- Triad colors: Three evenly spaced colors on the wheel [11]

Online tools such as Color Supply, Sessions College Color Calculator, and Rapid Tables Color Wheel can assist in developing visually appealing and scientifically accurate color palettes [11].

Accessibility Considerations for Color Vision Deficiency

Approximately 8% of men and 0.5% of women experience some form of color vision deficiency, making accessibility considerations critical in scientific figure design [11]. To ensure figures are interpretable by all readers:

- Avoid color-only coding: Use differing fill patterns, shapes, or direct labels to complement color distinctions [11]

- Ensure sufficient lightness contrast: Colors with widely different lightness levels remain distinguishable when converted to grayscale [11]

- Utilize accessibility tools: Online resources like WebAIM's Contrast Checker and ColorBrewer's "Colorblind Safe" option help identify accessible color combinations [11]

The diagram below outlines a strategic workflow for developing effective research programs in chemical biology, integrating computational and experimental approaches.

The future of chemical biology lies in increasingly sophisticated integration of synthetic chemistry with biological systems. Key frontiers include the development of next-generation bioorthogonal reactions with enhanced kinetics and biocompatibility for clinical translation, the refinement of chemoenzymatic strategies for sustainable synthesis of complex molecules, and the application of advanced quantitative techniques to achieve predictive understanding of living systems. As the field evolves, overcoming the grand challenges of bio-inspired synthesis will progressively illuminate the fundamental principles governing biological function, ultimately enabling unprecedented capabilities in therapeutic development, diagnostic imaging, and sustainable bioproduction.

The trajectory of chemical biology points toward a future where the boundaries between synthetic and biological systems become increasingly blurred. By embracing interdisciplinary training that spans chemical synthesis, biological analysis, and computational modeling, the next generation of researchers will be equipped to address these integrative challenges. Through continued innovation at this dynamic interface, chemical biology will play an increasingly pivotal role in advancing both fundamental scientific knowledge and transformative technological applications for human health and sustainable industry.

Organic synthesis provides the fundamental foundation for advancing chemical biology, serving as the primary engine for constructing molecules that probe, modulate, and mimic biological systems. This discipline enables the precise construction of small molecules, natural product analogues, molecular probes, and modified biomacromolecules that are inaccessible through biosynthetic methods alone [8]. The structural precision afforded by synthetic chemistry is indispensable for mechanistic biological studies and therapeutic development, particularly in addressing the grand challenges of understanding complex living systems [8]. In the context of increasing movement toward bioinspired and bio-integrated strategies—including biocatalysis, chemoenzymatic cascades, metabolic engineering, and bio-orthogonal chemistry—organic synthesis remains the critical backbone that enables these interdisciplinary approaches to move forward [8].

The unique value of organic synthesis in chemical biology lies in its ability to deliver molecules with exact structural specifications, enabling researchers to establish clear structure-activity relationships and develop precise tools for interrogating biological systems. Unlike purely biological approaches, synthetic chemistry allows for the incorporation of non-natural elements, stable isotopes, and specific functional groups that facilitate the study of biological mechanisms. Furthermore, synthetic approaches provide routes to molecules that may be difficult or impossible to obtain from natural sources, ensuring a reliable and sustainable supply of valuable compounds for research and development [8]. As chemical biology continues to evolve into a more translational discipline [2], the role of organic synthesis becomes increasingly critical in bridging the gap between basic biological understanding and therapeutic applications.

Molecular Probe Design and Construction

Fundamental Design Principles

The construction of effective molecular probes requires careful balancing of multiple design parameters to ensure biological relevance and experimental utility. Target specificity remains paramount, as off-target interactions can compromise data interpretation and lead to erroneous conclusions. Contemporary probe design increasingly incorporates bioorthogonal handles—chemical functionalities that can undergo selective reactions with detection tags in biological environments without interfering with native biochemical processes [8]. These handles enable subsequent labeling, purification, or visualization after the probe has engaged its target in a native biological context.

Additional critical considerations include physicochemical properties that govern cellular permeability and distribution, such as logP, polar surface area, and hydrogen bonding capacity. Metabolic stability must also be optimized to ensure sufficient half-life for experimental observation, while maintaining compatibility with the biological system under study. The emergence of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) has revolutionized this optimization process by enabling rapid parallel assessment of multiple structural variants against biological targets [12]. This approach allows researchers to explore a broader chemical space while consuming less time and material resources than traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization.

Representative Probe Classes and Their Applications

Table 1: Major Classes of Molecular Probes and Their Key Characteristics

| Probe Class | Key Structural Features | Primary Applications | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule Fluorescence Probes | Fluorophore conjugated to target-binding moiety | Live-cell imaging, localization studies, real-time tracking | G-quadruplex probes [13] |

| G4-Binding Metal Complexes | Coordinated metal center with planar aromatic ligands | Nucleic acid structure probing, therapeutic development | Metal-based G4 stabilizers [13] |

| Bioconjugation Probes | Cross-linking agents, bioorthogonal handles | Protein-protein interaction mapping, post-translational modification tracking | Click chemistry reagents [8] |

| Photoactivatable Probes | Photolabile protecting groups, caged compounds | Spatiotemporal control of bioactivity, precision targeting | Light-activated bioorthogonal reagents [8] |

Small-molecule fluorescence probes represent one of the most widely used tool classes in chemical biology. These typically consist of a target-binding moiety conjugated to a fluorophore, enabling visualization of the probe's localization and abundance within biological systems. Recent advances have produced increasingly sophisticated designs with improved brightness, photostability, and environmental sensitivity (e.g., turn-on probes that fluoresce only upon target binding) [13].

G-quadruplex (G4) binding probes illustrate the power of synthetic chemistry in creating tools for studying challenging biological targets. G4 structures are non-canonical nucleic acid conformations that play important roles in gene regulation, telomere maintenance, and other fundamental processes [13]. Synthetic approaches have yielded diverse G4-binding scaffolds, including porphyrins (e.g., TMPyP4), acridines (e.g., BRACO-19), and more complex structures like Pyridostatin (PDS) [13]. These tools have been instrumental in elucidating the biological functions of G4 structures and exploring their therapeutic potential.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Workflows

The implementation of high-throughput experimentation has transformed the process of probe optimization and reaction discovery in organic synthesis. HTE involves the miniaturization and parallelization of reactions, allowing for the rapid exploration of chemical space with minimal consumption of precious starting materials [12]. A standard HTE workflow encompasses several distinct phases:

- Experiment Design: Strategic selection of reaction variables (catalysts, ligands, solvents, additives) based on literature precedent and mechanistic hypotheses.

- Plate Preparation: Assembly of reaction components in microtiter plates (MTPs) using automated liquid handling systems.

- Reaction Execution: Performing transformations under controlled atmosphere and temperature conditions.

- Analysis and Data Processing: High-throughput analysis (often via LC-MS or NMR) with automated data interpretation.

- Data Management: Storage and curation of results following FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) [12].

The power of HTE is greatly enhanced through integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms. These tools can identify patterns in complex multidimensional data sets, predict promising reaction conditions, and guide iterative optimization cycles [12].

Reproducible Synthesis Protocols

Ensuring reproducibility in synthetic procedures is essential for the advancement of chemical biology. Organizations like Organic Syntheses address this challenge through rigorous verification protocols, requiring that procedures be successfully repeated in the laboratory of a member of the Board of Editors before publication [14]. Key elements of reproducible synthesis include:

- Detailed Reaction Setup: Comprehensive description of apparatus, including flask size and type, number of necks, and how each neck is equipped. Photographs of the setup are often required [14].

- Standardized Purification Methods: Detailed protocols for purification techniques such as flash column chromatography, preparative thin layer chromatography, or sublimation [15].

- Comprehensive Characterization: Full spectroscopic and analytical data for all compounds, including NMR spectra with calculations printed directly on them when quantitative NMR is employed [14].

For reactions conducted on scales between 2-50 g, authors must provide precise quantities of all reactants, with careful attention to significant figures. Any reagent used in significant excess (e.g., more than 1.5 equivalents) requires explanation in a Note, and the consequences of using lesser amounts should be discussed [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Probe Construction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Probe Development | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioorthogonal Reaction Components | Tetrazines, strained alkynes, azides | Selective labeling in biological environments | Stability in aqueous buffer, kinetics optimization [8] |

| Catalytic Systems | Organocatalysts, artificial metalloenzymes | Enabling challenging transformations | Compatibility with biological macromolecules [8] |

| Specialized Solvents | t-Butyl methyl ether (MTBE) substitutes | Green chemistry applications | Reduced hazard profile [14] |

| Building Blocks | Non-canonical amino acids, modified nucleotides | Incorporation of novel functionality | Orthogonality to native biological components [8] |

| Analytical Standards | qNMR reference standards | Quantitative analysis of probe purity | High purity, stability [14] |

The effectiveness of molecular probe development relies heavily on the quality and appropriate selection of research reagents. Bioorthogonal reaction components represent particularly valuable tools, with tetrazine ligations and strained alkynes showing special utility for selective labeling in living systems [8]. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2022 awarded for click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry underscored the transformative impact of these reagents [8].

Catalytic systems have evolved significantly to meet the challenges of constructing complex molecular probes. Beyond traditional metal catalysts, the field has seen advancement in organocatalysts and artificial metalloenzymes that can perform difficult or previously impossible transformations [8]. Directed evolution of enzymes, recognized by the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Frances Arnold, has provided powerful biocatalysts for asymmetric synthesis and green chemistry applications [8].

Software tools represent another critical component of the modern chemist's toolkit. Applications like ChemDraw facilitate the design, visualization, and communication of chemical structures, with advanced versions offering predictive capabilities for properties like pKa, NMR chemical shifts, and lipophilicity [16] [17]. The integration of these computational tools with experimental workflows has dramatically accelerated the design-make-test cycle in probe development.

Case Study: G-Quadruplex Targeting Tools

G-quadruplex (G4) structures represent an excellent case study in the development of precision molecular tools through organic synthesis. These non-canonical nucleic acid conformations form in guanine-rich regions of the genome and play important regulatory roles in replication, transcription, and telomere maintenance [13]. The structural diversity of G4 motifs—including parallel, antiparallel, and hybrid topologies—presents a significant challenge for tool development, requiring sophisticated synthetic approaches to achieve selective recognition [13].

The evolution of G4-targeting tools illustrates a progressive refinement from simple binding molecules to sophisticated multifunctional probes. Early tools like TMPyP4, a porphyrin derivative, demonstrated the ability to stabilize G4 structures and inhibit telomerase activity, but suffered from poor selectivity over duplex DNA [13]. Subsequent generations of tools addressed this limitation through structural modifications; for example, TQMP incorporated a phenolic ring to enhance selectivity [13]. Further advances produced compounds like BRACO-19 (a trisubstituted acridine) and RHPS4 (a pentacyclic system), which showed improved telomerase inhibitory activity and potential anticancer effects [13].

Pyridostatin (PDS) represents a significant milestone in G4 tool development, with a carefully designed aromatic arrangement that minimizes non-specific intercalation with duplex DNA while maintaining high affinity for G4 structures [13]. This design principle—optimizing selectivity through reduction of planar surface area—illustrates how synthetic chemistry can address fundamental biological challenges.

The translational potential of G4-targeting tools is exemplified by compounds that have advanced to clinical evaluation. CX-3543 (Quarfloxin) reached Phase II clinical trials for neuroendocrine carcinomas before being withdrawn due to efficacy and bioavailability limitations [13]. Its optimized analog, CX-5461 (Pidnarulex), advanced to Phase I trials but faced challenges related to phototoxicity and mutagenicity [13]. These clinical experiences highlight the ongoing challenges in transforming synthetic tools into viable therapeutics, particularly in balancing potency with appropriate pharmacological properties.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The integration of molecular probes into biological research requires careful planning of experimental workflows and understanding of the signaling pathways being investigated. The following diagram illustrates a generalized pathway for probe-mediated biological target engagement and detection, highlighting key steps where synthetic chemistry contributes crucial tools and methods.

The chemical biology platform integrates this probe engagement pathway into a broader framework for drug discovery and development. This approach uses multidisciplinary teams to accumulate knowledge and solve problems, often relying on parallel processes to speed development time and reduce costs [2]. The platform connects a series of strategic steps to determine whether a newly developed compound could translate into clinical benefit using translational physiology, which examines biological functions across multiple levels from molecular interactions to population-wide effects [2].

Future Directions and Grand Challenges

The future development of molecular probes and precision tools faces several significant challenges that will require innovations in synthetic methodology. Translation from model systems to living organisms, particularly humans for clinical applications, represents perhaps the most substantial hurdle [8]. The high reactivity required for sufficient yields at medically relevant concentrations must be balanced against stability, bioavailability, and toxicity considerations [8]. For bioorthogonal chemistry specifically, success in vivo depends on rapid reaction kinetics, appropriate pharmacokinetic properties of both reagents, and the ability to access target tissues in sufficient concentration [8].

The integration of synthetic and biological systems presents another major frontier. While living systems perform chemical transformations with precision that synthetic chemistry cannot yet match, hybrid approaches that combine the best features of both are showing increasing promise [8]. Chemoenzymatic strategies that combine enzymatic and chemical steps in a complementary fashion represent a powerful approach for installing complexity via enzymes, then elaborating via synthesis, or vice versa [8]. Recent interest in photobiocatalytic strategies—enzymatic processes that utilize electronically excited states accessed through photoexcitation—exemplifies the innovative directions this integration may take [8].

Sustainability and efficiency considerations are also driving methodology development. The principles of Green Chemistry, including solvent safety, atom economy, and waste minimization, are increasingly influential in probe design and synthesis [8]. Biomimetic catalysts that aim to reproduce active site features while maintaining robustness and recyclability represent one approach to addressing these concerns [8]. Similarly, the development of more sustainable solvents, such as using t-butyl methyl ether (MTBE) as a substitute for diethyl ether in large-scale work, reflects the growing importance of environmental considerations in synthetic planning [14].

The expanding role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in synthesis design represents perhaps the most transformative future direction. As HTE generates increasingly large and complex datasets, AI methods will become essential for identifying patterns, predicting reactivity, and optimizing reaction conditions [12]. The convergence of automated synthesis, AI-driven design, and robust biological screening platforms promises to accelerate the development of next-generation molecular tools with enhanced precision and utility for addressing fundamental questions in chemical biology.

The field of chemical biology faces a central grand challenge: living systems perform chemical transformations with an efficiency and precision that synthetic chemistry often cannot match in the laboratory [8]. This recognition has driven the field increasingly toward bioinspired and bio-integrated strategies that seek to emulate nature's synthetic prowess. Biomimetic synthesis represents a cornerstone of this approach, operating at the intersection of chemistry, biology, and materials science to develop new synthetic methodologies inspired by biological principles.

At its core, biomimetic synthesis studies how nature achieves specific reactions or synthesizes complex molecules and then applies those principles in organic synthesis [8]. This approach has evolved from a conceptual framework to an essential component of modern chemical biology, enabling access to complex molecular architectures with improved efficiency and selectivity. The field has gained significant momentum through its convergence with other disciplines, including biocatalysis, metabolic engineering, and bio-orthogonal chemistry, creating a powerful toolkit for addressing challenges in therapeutic development, molecular imaging, and sustainable production of complex molecules [8] [2].

This technical guide examines the current state of biomimetic synthesis within the broader context of chemical biology's grand challenges, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for implementing nature-inspired synthetic strategies.

Conceptual Foundations and Strategic Advantages

Biomimetic synthesis aims to replicate the processes and strategies found in nature, particularly those catalyzed by enzymes, to create more efficient and selective synthetic pathways for chemical transformations [8]. The conceptual framework rests on several key principles that distinguish it from traditional synthetic approaches:

- Metabolic Pathway Mimicry: Designing synthetic routes that mirror biosynthetic pathways, often employing cascade reactions that build molecular complexity rapidly

- Active Site Emulation: Developing synthetic catalysts that reproduce key features of enzyme active sites while maintaining robustness and recyclability

- Physiological Compatibility: Conducting transformations under mild, environmentally benign conditions similar to biological systems

The strategic advantages of biomimetic approaches are substantial and align with the growing emphasis on Green Chemistry goals, particularly solvent safety, atom economy, and waste minimization [8]. Bioinspired strategies frequently enable rapid assembly of complex natural product skeletons from simpler precursors through cascade reactions, cycloadditions, and C-H functionalizations [18]. This inherent efficiency often translates to reduced step counts, higher overall yields, and decreased environmental impact compared to linear synthetic sequences.

Table 1: Strategic Advantages of Biomimetic Synthesis Approaches

| Advantage | Mechanism | Impact on Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Step Economy | Cascade reactions mimicking biosynthetic pathways | Reduced synthetic steps, higher overall yields |

| Stereocontrol | Transition state mimicry of enzymatic processes | Superior stereoselectivity, reduced protection/deprotection |

| Sustainability | Mild conditions, aqueous compatibility | Reduced environmental impact, alignment with Green Chemistry |

| Structural Diversity | Biomimetic diversification of core scaffolds | Access to analog libraries for structure-activity studies |

Current Research and Representative Case Studies

Bioinspired Total Synthesis of Complex Natural Products

Recent advances in bioinspired synthesis showcase the power of this approach for constructing complex molecular architectures. A representative example is the total synthesis of chabranol, a terpenoid natural product with a novel bridged skeleton identified from soft corals [18]. The bioinspired strategy employed a Prins-triggered double cyclization to construct the core oxa-[2.2.1] bicycle in a single step, mimicking a proposed biosynthetic polycyclization (Figure 1).

The synthetic design was guided by a plausible biosynthetic pathway wherein a linear sesquiterpenoid precursor undergoes dihydroxylation and C–C bond cleavage to form an aldehyde intermediate. Under acidic conditions, this aldehyde undergoes a Prins cyclization with a trisubstituted olefin, generating a tertiary carbocation that is trapped stereoselectively by a chiral alcohol to form the bicyclic core [18]. This approach demonstrated excellent diastereoselectivity and provided supporting evidence for the proposed biosynthetic pathway.

Figure 1: Bioinspired synthetic strategy for chabranol featuring a key Prins-triggered double cyclization [18]

Biomimetic Oxidative Cyclization in the Monocerin Family

The application of biomimetic strategies to the synthesis of monocerin-family natural products demonstrates another powerful paradigm – the use of para-quinone methide (pQM) intermediates to construct complex heterocyclic systems [18]. Biosynthetically, the cis-substituted tetrahydrofuran (THF) ring in these molecules was proposed to form through benzylic oxidation generating a pQM intermediate, followed by an oxa-Michael addition (Figure 2).

This biomimetic oxidative cyclization strategy has been successfully implemented in laboratory synthesis, enabling efficient construction of the fused isocoumarin-THF ring system characteristic of this natural product family [18]. The approach highlights how proposed biosynthetic mechanisms can inspire efficient synthetic routes to complex molecular targets, particularly those with challenging stereochemical and functional group arrangements.

Figure 2: Biomimetic oxidative cyclization via para-quinone methide intermediates for THF ring formation [18]

Biomimetic Materials and Systems

Beyond natural product synthesis, biomimetic principles are being applied to materials science and systems chemistry. Recent advances include the development of cytomimetic calcification in chemically self-regulated prototissues, integrating enzyme-containing inorganic protocells into alginate hydrogels to produce matrix-integrated prototissues that mimic bone tissue calcification and decalcification processes [19]. These systems represent a convergence of biomimetic synthesis with materials science, enabling the creation of functional materials with life-like properties.

Another emerging area is the design of minimal biomimetic metal-binding peptides using bioinformatics approaches. Researchers have successfully designed an eight-amino-acid peptide that self-assembles with copper ions, forming a complex that mimics the laccase enzyme's active site [19]. This approach demonstrates how computational methods can enhance biomimetic design, creating simplified yet functional analogs of complex biological systems.

Table 2: Representative Biomimetic Synthesis Applications and Outcomes

| Target System | Biomimetic Strategy | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chabranol | Prins-triggered double cyclization | Concise synthesis (9 steps), structural confirmation | [18] |

| Monocerin-family | pQM-mediated oxidative cyclization | Efficient THF ring formation, supports biosynthetic proposal | [18] |

| Laccase mimic | Bioinformatics-designed peptide | Copper-binding complex with enzymatic activity | [19] |

| Bone tissue model | Cytomimetic prototissue assembly | Controlled calcification/decalcification cycles | [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Considerations for Biomimetic Reaction Design

Implementing biomimetic synthesis requires careful consideration of several experimental parameters to successfully replicate biological transformation principles:

- Reaction Medium: Many biomimetic reactions benefit from aqueous or biphasic systems that more closely mimic biological environments [8]

- Catalyst Design: Biomimetic catalysts should balance structural simplicity with functional complexity, often incorporating key elements of enzymatic active sites while maintaining synthetic practicality

- Condition Optimization: Biomimetic transformations often require extensive optimization of pH, temperature, and cofactor requirements to achieve efficient conversion

Protocol: Bioinspired Prins-Triggered Double Cyclization

The following detailed protocol adapts the key transformation from the chabranol synthesis [18]:

Reagents and Materials:

- Hydroxy aldehyde precursor (e.g., compound 3 in Scheme 1b of [18])

- Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM)

- Trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf)

- Anhydrous diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA)

- Molecular sieves (4Å), activated

- Inert atmosphere equipment (argon or nitrogen)

Procedure:

- Activate molecular sieves by flame-drying under vacuum and maintain under inert atmosphere

- Charge a dried round-bottom flask with the hydroxy aldehyde precursor (1.0 equiv) in anhydrous DCM (0.1 M concentration) under inert atmosphere

- Add activated 4Å molecular sieves (100 mg/mL) to the reaction mixture

- Cool the reaction mixture to -78°C using a dry ice/acetone bath

- Slowly add TMSOTf (1.2 equiv) dropwise via syringe, maintaining temperature at -78°C

- Stir the reaction at -78°C for 30 minutes, then warm gradually to 0°C over 2 hours

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS until complete consumption of starting material

- Quench the reaction by careful addition of saturated aqueous NaHCO₃ solution at 0°C

- Warm to room temperature, filter to remove molecular sieves, and extract with DCM (3 × 20 mL)

- Combine organic extracts, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure

- Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel

Key Considerations:

- Strict anhydrous conditions are essential for high yield

- The reaction typically proceeds with excellent diastereoselectivity (>20:1 dr)

- Scale-up may require adjusted addition rates to manage exothermicity

Protocol: Biomimetic Oxidative Cyclization via Quinone Methide

This protocol outlines the general approach for biomimetic oxidative cyclizations as applied to the monocerin-family synthesis [18]:

Reagents and Materials:

- Phenolic precursor with appropriate side-chain nucleophile

- Oxidizing agent (e.g., DDQ, CAN, or MnO₂)

- Anhydrous solvent (acetonitrile, DCM, or toluene)

- Buffer solutions for pH control (if required)

Procedure:

- Dissolve the phenolic precursor (1.0 equiv) in appropriate anhydrous solvent (0.05 M concentration)

- For reactions requiring specific pH, utilize buffer solution as cosolvent or additive

- Add oxidizing agent (1.1-2.0 equiv) portionwise at room temperature

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS until complete consumption of starting material

- If incomplete after 2-12 hours, consider heating or additional oxidant

- Quench reaction by dilution with water or mild reducing agent (Na₂S₂O₃)

- Extract with ethyl acetate or DCM (3 × 15 mL)

- Combine organic extracts, wash with brine, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄

- Concentrate under reduced pressure and purify by flash chromatography

Key Considerations:

- Oxidant selection critically influences yield and selectivity

- The reaction often proceeds through a transient quinone methide intermediate

- Stereochemical outcome may be influenced by solvent polarity and additives

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of biomimetic synthesis requires specialized reagents and catalysts designed to emulate biological transformations. The following table details key research reagent solutions for biomimetic applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomimetic Synthesis

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Biomimetic Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial metalloenzymes | Hybrid bio-inorganic catalysts | Combining transition metal catalysis with protein scaffolds | C-H activation, oxidative coupling [8] |

| Biomimetic organocatalysts | Small molecule enzyme mimics | Asymmetric catalysis without metals | Aldol reactions, conjugate additions [19] |

| Directed evolution enzymes | Engineered biocatalysts | Non-natural transformations | "New-to-nature" chemistry [8] [20] |

| Bio-orthogonal catalysts | Selective reactivity in biological systems | In vivo labeling and modifications | Tetrazine ligations, strained alkynes [8] |

| Biomimetic porphyrin complexes | Heme enzyme mimics | Oxidation catalysis under mild conditions | Aerobic oxidations, halogenations [19] |

Future Directions and Grand Challenges

The evolution of biomimetic synthesis continues to address fundamental challenges in chemical biology while expanding into new research domains. Several key frontiers are shaping the future of this field:

Integration with Systems Biology and Omics Technologies

Modern biomimetic synthesis increasingly leverages insights from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to guide synthetic strategy design [2]. The availability of extensive biosynthetic gene cluster data enables more informed biomimetic approaches that closely mirror actual biological pathways rather than speculative biosynthetic proposals. This integration represents a significant advancement in the precision and relevance of bioinspired strategies.

Sustainability and Green Chemistry Applications

Biomimetic synthesis aligns naturally with the principles of Green Chemistry, offering pathways to reduce waste, improve atom economy, and utilize renewable feedstocks [8]. Future developments will likely focus on biomimetic approaches to converting CO₂ into valuable products using engineered organisms, creating biodegradable polymers inspired by natural systems, and developing energy-efficient catalytic processes that operate under mild conditions [21].

Translational Challenges and In Vivo Applications

A critical frontier in biomimetic chemistry involves translation from model systems to living organisms and clinical applications [8]. Key challenges include:

- Reaction efficiency at medically relevant concentrations within biological timeframes

- Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of synthetic precursors and catalysts

- Stability and circulation time of reactive species in physiological environments

- Target specificity and minimization of off-target effects in complex biological systems

Addressing these challenges requires close collaboration between synthetic chemists, chemical biologists, and translational researchers to develop biomimetic systems capable of functioning within the constraints of living organisms.

Biomimetic synthesis represents a powerful paradigm for addressing grand challenges in chemical biology, offering efficient strategies for constructing complex molecules while aligning with sustainability goals. By learning from and emulating nature's synthetic principles, researchers can develop transformative approaches to natural product synthesis, materials science, and therapeutic development. As the field continues to evolve through integration with systems biology, computational design, and translational science, biomimetic strategies will play an increasingly central role in advancing chemical biology's frontier.

The convergence of chemistry, biology, and physics represents a fundamental shift in modern scientific inquiry, enabling researchers to address complex biological systems with unprecedented precision. This interdisciplinary approach is not merely the application of one discipline to another but represents the emergence of entirely new fields of study with their own methodologies and conceptual frameworks. Research in rapidly developing areas between the classical disciplines presents unique opportunities for groundbreaking discoveries that cannot be achieved within traditional disciplinary boundaries [22]. The integration of these fields has become central to understanding biological processes, as each discipline contributes essential tools and perspectives that, when combined, provide a more complete picture of biological complexity [23].

At the heart of this integration lies chemical biology, which uses molecular tools and principles from organic synthesis to study and manipulate biological systems [24]. This rapidly evolving discipline provides the fundamental capabilities for constructing and modifying molecules that can probe, modulate, or mimic biological functions with structural precision necessary for mechanistic studies and therapeutic development [24]. Meanwhile, physics contributes quantitative analytical tools and theoretical frameworks for understanding the forces, energies, and dynamic interactions that govern biological systems at multiple scales, from single molecules to entire organisms.

The grand challenge in this interdisciplinary space involves overcoming the distinctive difficulties of designing synthetic and analytical approaches compatible with the complexity of living systems, including mild reaction conditions, aqueous environments, functional group tolerance, and demands for stereoselectivity, all while maintaining scalability and environmental sustainability [24]. This whitepaper examines the core principles, methodologies, and future directions bridging these three foundational scientific disciplines, with particular emphasis on their application to chemical biology's most pressing challenges.

Grand Challenges in Chemical Biology

Bioorthogonal Chemistry for Living Systems

Bioorthogonal chemistry represents one of the most significant advances at the chemistry-biology interface, referring to chemical reactions that can occur within living organisms without interfering with natural biochemical processes [24]. These reactions, particularly "click" chemistry reactions, are defined by stringent criteria including modularity, wide scope, high yield, stereospecificity, and generation of inoffensive byproducts [24]. The field earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2022 for Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Morten Meldal, and K. Barry Sharpless, recognizing its transformative potential for in vivo imaging, drug delivery, and prodrug activation [24].

The central challenge in bioorthogonal chemistry involves translation from model systems to living organisms, particularly humans for clinical applications [24]. Performing reactions in a chemical laboratory differs significantly from delivering reactions in living patients. Key obstacles include:

- Reaction Kinetics: High reactivity is crucial to obtain sufficient yields at medically relevant concentrations within available reaction times [24]

- Reagent Stability: Reagents with limited stability or circulation time must react rapidly enough to elicit desired effects before clearance or degradation [24]

- Bioavailability: The degree to which components can access circulation and reach target areas unencumbered determines reaction success in vivo [24]

- Pharmacokinetics: Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties dictate in vivo behavior of both reagents [24]

Organic synthesis addresses these challenges by designing reagents with fast kinetics, minimal toxicity, and functional group tolerance under physiological conditions. Recent developments include tetrazine ligations, strained alkynes, and light-activated or redox-triggered reactions [24]. All factors influencing in vivo applicability depend on a drug's chemical structure, translating directly into challenges for synthetic organic chemistry to design molecules that meet both chemical and biological requirements simultaneously [24].

Biocatalysis and Biomimetic Synthesis

Biocatalysis utilizes biological catalysts, primarily enzymes or whole cells, to promote chemical reactions with high selectivity under mild, environmentally benign conditions [24]. This approach mimics how living systems perform chemical transformations under conditions and with precision that synthetic chemistry cannot reach [24]. The field has advanced significantly through directed evolution of enzymes, earning Frances Arnold the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for engineering improved enzyme performances by applying principles of evolution through random gene mutation and natural selection [24].

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain:

- Limited Reaction Scope: Extending enzyme utility to non-natural substrates and reactions such as C-H activation or oxidative coupling remains difficult [24]

- Artificial Catalyst Design: Mimicking enzymatic transformations with synthetic catalysts, including organocatalysts or artificial metalloenzymes, faces obstacles in selectivity, scalability, and green chemistry compatibility [24]

- Enzyme Engineering: Researchers manipulate enzymes through side-chain derivatization or introduction of non-canonical residues to perform difficult or previously impossible reactions [24]

Biomimetic reactions represent another strategic approach, where chemical reactions mimic processes and strategies found in nature, particularly those catalyzed by enzymes [24]. These processes are designed to imitate biological systems to create more efficient and selective synthetic pathways. Biomimetic catalysts aim to reproduce active site features while maintaining robustness and recyclability, aligning with Green Chemistry goals regarding solvent safety, atom economy, and waste minimization [24].

Challenges in biomimetic synthesis include technical difficulties controlling stereoselectivity, achieving high yields, addressing scalability issues for industrial production, and avoiding expensive or environmentally hazardous reagents [24]. The complexity of translating natural systems into laboratory protocols presents additional hurdles that require continued innovation in catalyst design and process integration [24].

Natural Product Synthesis and Engineering

Natural products represent a rich source of complex bioactive structures that have inspired chemical biology for decades [24]. However, transforming natural products into viable medicines faces significant challenges in acquiring adequate amounts of original compounds and their structural variants to support research and large-scale manufacturing [24]. Natural products are finite resources whose consistent availability is threatened by resource depletion and environmental variability [24].