Global Optimization Algorithms for Molecular Structure: Advancing Precision in Drug Discovery

This article explores the pivotal role of global optimization algorithms in enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of molecular structure determination for drug discovery.

Global Optimization Algorithms for Molecular Structure: Advancing Precision in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of global optimization algorithms in enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of molecular structure determination for drug discovery. It provides a comprehensive examination of foundational concepts, core algorithmic methodologies, and their direct applications in predicting molecular interactions and optimizing drug candidates. The content addresses critical challenges such as convergence on local minima and high computational cost, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. By presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of algorithm performance on benchmark functions and real-world case studies, this resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and implement the most effective optimization techniques, ultimately accelerating the development of targeted therapeutics.

The Foundation of Molecular Optimization: From Problem Formulation to Algorithmic Principles

The prediction of a molecule's stable three-dimensional structure represents one of the most fundamental challenges in computational chemistry and structural biology. This process is intrinsically a global optimization problem because it requires finding the molecular configuration that corresponds to the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) on a complex, high-dimensional potential energy surface. The computational difficulty arises from the fact that the number of possible configurations grows exponentially with the number of degrees of freedom in the molecule, creating a vast search space punctuated by numerous local minima that can easily trap conventional optimization algorithms. This "multiple minima" problem has been recognized for decades, with early researchers noting that even small protein sequences exhibit astronomically many possible conformations [1]. The core challenge lies in efficiently navigating this rugged energy landscape to identify the true global minimum without becoming trapped in suboptimal local minima, which represents a metastable state rather than the biologically relevant native structure.

Quantitative Landscape of the Optimization Challenge

Algorithm Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Sample Efficiency of Molecular Optimization Algorithms on PMO Benchmark Tasks [2]

| Algorithm Category | Representative Methods | Average Performance (10K Query Budget) | Success Rate on Challenging Tasks | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep RL-based | MolDQN, GCPN | Comparable to predecessors | Variable; fails on certain problems | Requires careful reward engineering |

| Generative Models | Grammar-VAE, MolGAN | Lower sample efficiency | Limited by training data bias | Struggles with latent space optimization |

| Traditional GO | CGU, Monte Carlo | Method-dependent | Can solve specific problem classes | Exponential time complexity worst-case |

| Hybrid Approaches | Not specified | Emerging | Potentially broader applicability | Balancing exploration vs. exploitation |

Complexity Metrics for Molecular Optimization Problems

Table 2: Characteristics of Molecular Structure Prediction Problems [3] [4]

| Problem Type | Search Space Dimension | Key Energy Landscape Features | State-of-the-Art Approaches | Approximation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Side-chain Prediction | n residues × R rotamers/residue | Sparse but rugged | Dead-end elimination, MILP, R³ | Rotamer libraries [4] |

| Molecular Conformation | 3N-6 degrees of freedom (N: atoms) | Correlated, high barrier | Stochastic methods, hybrid algorithms | Distance geometry, constraints |

| Crystal Structure Prediction | Unit cell + molecular coordinates | Periodically constrained | DFT-based sampling, random search | Empirical force fields |

| Reaction Pathway Mapping | Collective variables | Saddle points, transitions | Nudged elastic band, string methods | Reduced dimensionality [3] |

Methodological Framework: Global Optimization Approaches

Algorithmic Taxonomy and Implementation

Molecular global optimization methods are broadly categorized into stochastic and deterministic approaches, each with distinct exploration strategies and theoretical foundations [3]. Stochastic methods, including Monte Carlo algorithms and evolutionary approaches, incorporate random steps to escape local minima and have historically been important for addressing the multiple-minima problem in protein folding [1]. Deterministic methods, such as the convex global underestimator (CGU) approach, provide mathematical guarantees of convergence but may face scalability challenges with molecular complexity. Modern implementations increasingly leverage hybrid algorithms that combine the strengths of multiple paradigms, integrating accurate quantum methods with efficient search strategies to address increasingly complex chemical systems [3].

Detailed Protocol: Protein Side-Chain Prediction Using Mixed-Integer Linear Programming

The protein side-chain prediction (SCP) problem exemplifies the combinatorial nature of molecular optimization, requiring the identification of optimal side-chain conformations for a fixed protein backbone [4].

Protocol Steps:

Input Preparation and Rotamer Library Selection

- Obtain the three-dimensional coordinates of the protein backbone from experimental data or homology modeling.

- Select an appropriate rotamer library (e.g., Dunbrack rotamer library) containing statistically significant side-chain conformations observed in experimental structures.

- Define the set of residues N = {1, 2, ..., n} for conformation prediction and their corresponding rotamer sets R_i for each residue i.

Energy Function Parameterization

- Calculate the self-energy terms c_ir for each rotamer r of residue i, representing interactions with the backbone.

- Compute pairwise interaction energies p_irjs between rotamer r of residue i and rotamer s of residue j for all interacting residue pairs.

- Apply distance-dependent cutoff (typically 5-7Å) to identify interacting residue pairs and reduce computational complexity.

Mathematical Programming Formulation

- Implement the Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) formulation:

- Define binary variables yir = 1 if rotamer r is selected for residue i, 0 otherwise.

- Define binary variables xirjs = 1 if rotamer r is selected for residue i AND rotamer s is selected for residue j, 0 otherwise.

- Objective: Minimize Σ(i,r) cir yir + Σ(i,r,j,s) pirjs xirjs

- Constraints:

- Σ(r∈Ri) yir = 1 for each residue i (each residue selects exactly one rotamer)

- xirjs = yir × yjs for all interacting pairs (linearization constraints)

- Implement the Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) formulation:

Solution and Refinement

- Apply the Residue-Rotamer Reduction (R³) algorithm or similar graph-based decomposition to identify independent subproblems and reduce problem size [4].

- Utilize MILP solvers (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) to obtain the global minimum energy configuration.

- Perform local energy minimization using continuous optimization to relax discrete rotamer positions and account for continuous degrees of freedom.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Computational complexity increases exponentially with problem size; for large proteins (>500 residues), consider divide-and-conquer approaches.

- Solution quality depends critically on the accuracy of the energy function and completeness of the rotamer library.

- Dead-end elimination (DEE) preprocessing can significantly reduce the problem space before MILP solution [4].

Detailed Protocol: Molecular Optimization via Deep Reinforcement Learning (MolDQN)

The MolDQN framework formulates molecular optimization as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), combining domain knowledge of chemistry with deep reinforcement learning to ensure 100% chemical validity [5].

Protocol Steps:

Problem Formulation as Markov Decision Process

- State Space (S): Define each state s ∈ S as a tuple (m, t) where m is a valid molecule and t is the number of steps taken (0 ≤ t ≤ T).

- Action Space (A): Define chemically valid modifications:

- Atom Addition: Add an atom from permitted elements and form valence-allowed bonds to existing atoms.

- Bond Addition: Increase bond order between two atoms with free valence (single→double, double→triple, etc.).

- Bond Removal: Decrease bond order between atoms (triple→double, double→single, single→no bond).

- State Transition (P_sa): Deterministic transitions where applying action a to molecule m yields new molecule m'.

- Reward Function (R): Define based on target molecular properties, with time discounting (γ^(T-t)) to prioritize terminal states.

Reinforcement Learning Implementation

- Implement Double Q-learning with randomized value functions to stabilize training.

- Design Deep Q-Network (DQN) architecture to approximate action-value function Q(s, a).

- Apply experience replay to break temporal correlations in training data.

- For multi-objective optimization, implement weighted sum of rewards: Rtotal = w1R1 + w2R2 + ... + wnR_n.

Training Procedure

- Initialize replay buffer and Q-network with random weights.

- For each episode:

- Start from initial molecule (or random valid molecule).

- For each step (up to maximum T):

- Select action using ε-greedy policy (balance exploration vs. exploitation).

- Execute action, observe reward and next state.

- Store transition (s, a, r, s') in replay buffer.

- Sample random mini-batch from replay buffer.

- Compute temporal difference targets and update Q-network parameters.

- Validate performance on benchmark tasks (e.g., QED, penalized logP) [5].

Validation and Analysis:

- Monitor chemical validity rate (should maintain 100% with proper action constraints).

- Track property improvement across training episodes.

- Visualize optimization paths through chemical space to understand model behavior.

Visualization: Conceptual Framework

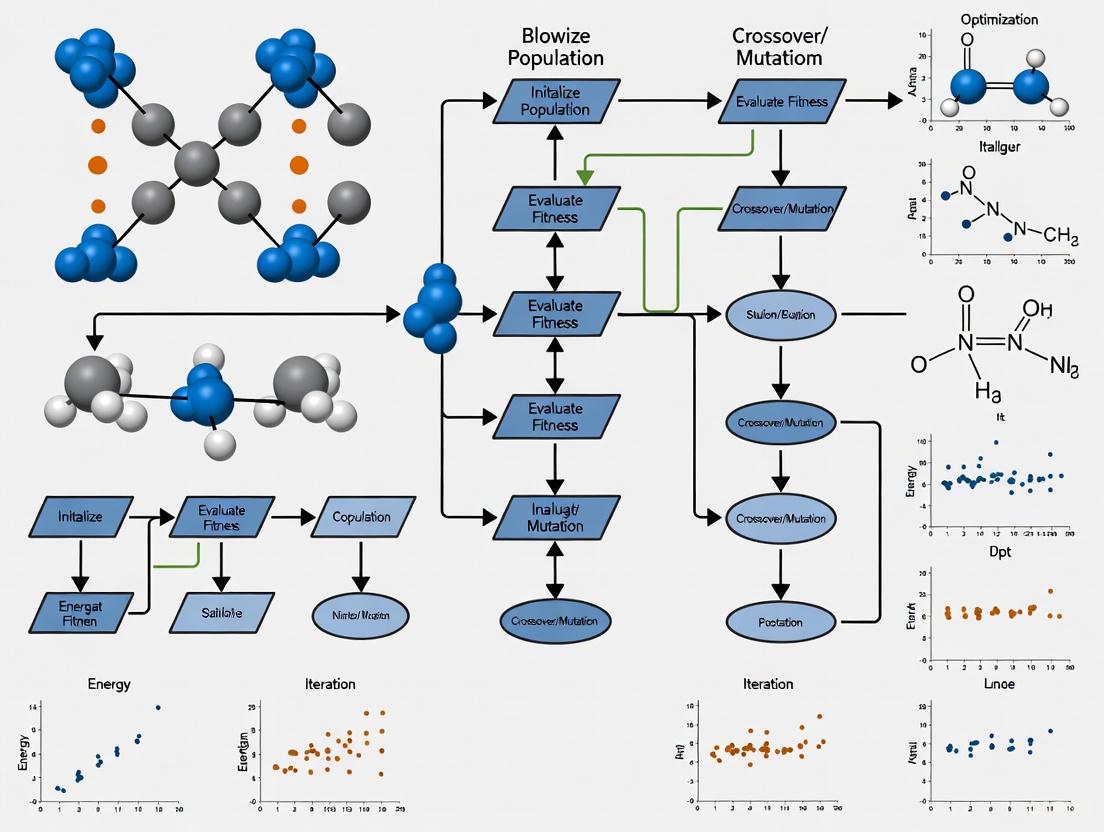

Figure 1: Molecular Structure Prediction as a Global Optimization Problem. This framework illustrates how the fundamental challenges in molecular structure prediction necessitate global optimization approaches, with different strategies applied across various scientific domains.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Optimization [5] [6] [4]

| Reagent/Software | Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotamer Libraries | Data Resource | Discrete side-chain conformation sets | Protein side-chain prediction [4] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Chemical validity maintenance, descriptor calculation | Molecule manipulation in MolDQN [5] |

| SCAGE Framework | Deep Learning | Molecular property prediction with conformer awareness | Pretraining for molecular optimization [6] |

| MMFF Force Field | Molecular Mechanics | Conformation generation and energy evaluation | Stable conformation sampling [6] |

| DEE Algorithms | Optimization | Search space reduction via domination arguments | Preprocessing for protein design [4] |

| MILP Solvers | Mathematical Programming | Global optimization of discrete formulations | Side-chain positioning, protein design [4] |

Molecular structure prediction remains fundamentally a global optimization challenge due to the exponentially large conformational space and the rugged nature of the molecular energy landscape. While significant advances have been made in both algorithmic approaches and computational frameworks, current methods still face limitations in sample efficiency and ability to solve certain molecular optimization problems within practical computational budgets [2]. Future directions include the integration of accurate quantum methods with efficient global search strategies, the development of more flexible hybrid algorithms, and the potential application of quantum computing to address increasingly complex chemical systems [3]. The continued development of standardized benchmarks like PMO will enable more transparent evaluation of algorithmic advances and facilitate progress in this critical domain at the intersection of chemistry, computational science, and molecular engineering. As these methods mature, they hold the promise of dramatically accelerating molecular discovery and design across pharmaceutical, materials, and biotechnology applications.

In molecular sciences, the potential energy surface (PES) is a fundamental concept that describes the energy of a system as a function of the positions of its constituent atoms. This high-dimensional surface is characterized by local minima (stable molecular configurations), transition states (saddle points representing energy barriers between minima), and pathways connecting these stationary points [7]. The "local minima problem" refers to the significant challenge of navigating this complex landscape to find the global minimum—the most stable configuration—without becoming trapped in local low-energy states. This problem is particularly acute in molecular structure research, where the PES is exceptionally rugged, and exhaustive sampling is computationally prohibitive [3] [8].

Understanding the global organization of the energy landscape is critical for predicting molecular kinetics, stability, and function. For instance, the organization of minima and transition states directly determines thermodynamic properties and reaction rates [7]. Computational methods for global optimization aim to overcome local minima by employing strategies that either tunnel through or circumvention energy barriers, enabling efficient exploration of the vast configurational space [8].

Quantitative Profiling of Molecular Energy Landscapes

Systematic analysis of kinetic transition networks (KTNs) provides quantitative insights into the complexity of molecular energy landscapes. The following table summarizes key topological metrics for common organic molecules, derived from the Landscape17 dataset, which provides complete KTNs computed using hybrid-level density functional theory [7].

Table 1: Complexity Metrics for Molecular Kinetic Transition Networks

| Molecule | Number of Minima | Number of Transition States | Approximate Computational Cost (CPU hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 2 | 2 | Not Specified |

| Malonaldehyde | 2 | 4 | Not Specified |

| Salicylic Acid | 7 | 11 | Not Specified |

| Azobenzene | 2 | 4 | Not Specified |

| Paracetamol | 4 | 9 | Not Specified |

| Aspirin | 11 | 37 | Not Specified |

| Total (Landscape17) | 28 | 67 | >100,000 |

The data reveals that even small molecules can possess surprisingly complex landscapes. Aspirin, for example, features at least 11 distinct minima interconnected by 37 transition states [7]. This complexity underscores the challenge of locating the global minimum and achieving adequate sampling for kinetic predictions.

The performance of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) in reproducing these reference landscapes can be quantitatively benchmarked. Current state-of-the-art models face significant challenges, as illustrated in the following performance summary.

Table 2: Performance Benchmark of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials on Landscape17

| Performance Metric | Typical Value for Current MLIPs | Implication for Landscape Reproduction |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Transition States | >50% | Incomplete kinetic networks, inaccurate reaction rates |

| Unphysical Stable Structures | Present throughout PES | Spurious minima trap simulations and corrupt sampling |

| Improvement with Pathway Data Augmentation | Significant | Enhanced reproduction of DFT PES and global kinetics |

Despite achieving low force and energy errors on standard benchmarks, MLIPs often fail to capture the global topology of the PES. Data augmentation with configurations sampled along reaction pathways has been shown to significantly improve model performance, though underlying architectural challenges remain [7].

Experimental Protocols for Landscape Exploration

Protocol 1: Constructing a Kinetic Transition Network

Objective: To map the key minima and transition states of a molecular system for global kinetics analysis [7].

Materials:

- Software: Global optimization package (e.g.,

TopSearch[7]), electronic structure code (e.g., for Density Functional Theory calculations). - Hardware: High-performance computing cluster.

Procedure:

- Global Minimum Search: Initiate a basin-hopping global optimization to identify the lowest-energy minimum and other low-lying minima [7] [9].

- Transition State Location: From each located minimum, perform single-ended and double-ended transition state searches to find first-order saddle points connecting them [7].

- Pathway Calculation: For each confirmed transition state, compute the approximate steepest-descent paths connecting it to the two associated minima. This involves displacing the geometry along the normal mode corresponding to the imaginary frequency and minimizing the energy [7].

- Network Validation: Check for permutational isomers and structures related by symmetry to avoid duplicates in the network [7].

- Data Compilation: Assemble the final KTN dataset, including for all stationary points: atomic coordinates, energies, forces, and Hessian eigenspectra; and for the pathways: positions, energies, and forces [7].

Protocol 2: Machine-Learning-Enabled Barrier Circumvention

Objective: To employ extended degrees of freedom for global structure optimization, circumventing energy barriers encountered in conventional landscapes [8].

Materials:

- Software: Bayesian global optimization framework (e.g., BEACON, GOFEE) capable of handling vectorial fingerprints with extra dimensions [8].

- Hardware: Computing resources for on-the-fly training of a Gaussian Process surrogate model.

Procedure:

- Define Extended Configuration Space:

- Hyperspace: Embed the 3D atomic coordinates into a higher-dimensional space (e.g., 4-6 dimensions) [8].

- Chemical Identity (ICE): For selected atoms, define continuous variables

q_i,e ∈ [0,1]representing the degree to which atomiis elemente[8]. - Atom Existence (Ghost): Introduce "ghost" atoms to allow interpolation between an atom and a vacancy, conserving the total elemental composition [8].

- Train Surrogate Model: Use a Gaussian Process to learn the relationship between the extended-configuration fingerprint and the system's energy/forces, trained on a sparse set of initial DFT calculations [8].

- Bayesian Search Loop:

- Probe Landscape: Use the surrogate model to propose promising candidate structures in the extended space that have low energy or high uncertainty [8].

- Evaluate Candidates: Select the most promising candidates and evaluate their true energy and forces using DFT [8].

- Update Model: Augment the training data with the new DFT results to iteratively improve the surrogate model [8].

- Project to Physical Space: Once the global minimum is identified in the extended space, project the solution back to a purely 3D structure with definite chemical identities [8].

Diagram 1: ML-enabled barrier circumvention workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Energy Landscape Exploration

| Tool Name/Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TopSearch | Python package for automated landscape exploration | Kinetic Transition Network construction; identifies minima and transition states [7]. |

| BEACON/GOFEE | Bayesian optimization frameworks | Uncertainty-guided global search for atomic structures; integrates with ML models [8]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electronic structure method | Provides high-accuracy energies and forces for training and validation [7] [8]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Surrogate energy models | Accelerates molecular simulations; requires careful benchmarking on KTNs [7]. |

| Landscape17 Dataset | Benchmark KTNs for small molecules | Standardized test suite for validating MLIP accuracy and kinetic reproducibility [7]. |

| Disconnectivity Graphs | Landscape visualization tool | Tree diagrams mapping minima and barrier heights; reveals functional landscape topology [10]. |

| Persistent Homology | Topological data analysis | Quantifies landscape features (basins, loops) from data; enables rigorous comparison [10]. |

Diagram 2: Conceptual relationship of core principles and methods.

The Role of High-Dimensionality and Computational Cost in Molecular Modeling

Molecular modeling operates within high-dimensional configuration spaces where the number of degrees of freedom grows exponentially with system size, presenting fundamental challenges known as the curse of dimensionality. In practical terms, simulating a relatively small protein-ligand complex can involve thousands of atomic coordinates, creating a potential energy surface (PES) with numerous local minima that must be navigated to identify globally optimal structures. This high-dimensional nature severely complicates the search for stable molecular configurations, as the computational cost of exhaustive sampling becomes prohibitive. The global molecular modeling market, valued at USD 4.22 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 12.42 billion by 2032 with a CAGR of 14.43%, reflects the substantial resources being allocated to address these computational challenges [11].

The curse of dimensionality manifests in molecular modeling through several interconnected phenomena: it obscures meaningful correlations among features, introduces significant redundancy, and complicates the discovery of robust patterns that accurately predict molecular behavior and properties. As dimensionality increases, classifier performance typically improves up to a point, beyond which it deteriorates rapidly due to the exponential growth of the search space and the sparsity of meaningful data within it. Furthermore, the computational cost of processing high-dimensional data increases substantially, resulting in scalability issues and inefficiencies in both model training and inference phases [12]. These challenges necessitate sophisticated computational strategies that can navigate high-dimensional spaces while maintaining tractable computational costs.

Computational Methods and Dimensionality Reduction

Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

Dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques represent a critical approach for addressing high-dimensional challenges in molecular modeling by transforming complex datasets into more compact, lower-dimensional representations while preserving essential structural information. These methods can be broadly categorized into linear approaches, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and nonlinear techniques, including Kernel PCA (KPCA), t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). PCA operates by identifying orthogonal directions (principal components) that maximize variance in the data through eigen-decomposition of the covariance matrix, providing an interpretable linear transformation that preserves global structure. However, PCA assumes linear relationships and struggles with complex nonlinear structures prevalent in molecular systems [13].

Nonlinear DR methods address these limitations: KPCA extends PCA by employing the kernel trick to capture nonlinear structures through implicit mapping to high-dimensional feature spaces, while t-SNE and UMAP excel at preserving local relationships and neighborhood structures, making them particularly valuable for visualization and exploratory analysis of molecular datasets. The computational trade-offs between these approaches are significant—PCA offers computational efficiency with O(n³) complexity for eigen-decomposition, while KPCA requires O(n³) operations on an n×n kernel matrix, becoming prohibitive for large datasets [13]. Sparse KPCA addresses this limitation by selecting a subset of representative training points (m ≪ n), significantly reducing computational complexity to O(m³) while approximating the full kernel solution [13].

Hybrid and Regularized Frameworks

Recent advances have focused on hybrid DR techniques that integrate multiple approaches to overcome limitations of individual methods. One innovative framework combines PCA with Restricted Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) through an adaptive graph regularization mechanism. This approach synergistically leverages PCA's global linear projection capabilities with RBMs' nonlinear feature learning strengths while preserving local topological relationships through dynamically updated similarity-based neighborhood graphs [12]. The regularization promotes consistency between neighboring data points in the original input space and their representations in the reduced feature space, achieving balanced preservation of both global and local data structures.

Another emerging trend involves the integration of deep learning architectures with traditional DR methods. Neural network-based models including autoencoders, Deep Belief Networks (DBNs), and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are increasingly combined with PCA, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and mutual information-based feature selection. This synergistic integration enables extraction of hierarchical and semantically meaningful features by leveraging complementary strengths to capture both linear and nonlinear structures within high-dimensional molecular datasets [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods in Molecular Modeling

| Method | Mathematical Foundation | Computational Complexity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Eigen-decomposition of covariance matrix | O(n³) for n samples | Fast, preserves global structure, interpretable | Assumes linearity, sensitive to outliers |

| Kernel PCA | Kernel trick with eigen-decomposition | O(n³) | Captures nonlinear patterns | High memory usage (O(n²)), no inverse mapping |

| Sparse KPCA | Reduced eigen-decomposition | O(m³) with m ≪ n | Enables large dataset application | Approximation accuracy depends on subset selection |

| t-SNE/UMAP | Neighborhood probability matching | O(n²) | Excellent local structure preservation | Computational cost limits large-scale application |

| PCA-RBM Hybrid | Graph-regularized neural network | Varies with architecture | Captures both global and local structures | Complex implementation, training instability risk |

Advanced Optimization Algorithms

Machine Learning-Enabled Global Optimization

Traditional global optimization methods for molecular structure prediction face significant challenges in navigating high-dimensional potential energy surfaces with numerous local minima. Recent machine learning approaches have fundamentally expanded available strategies by introducing novel variables implemented within atomic fingerprints. One innovative method incorporates extra dimensions describing: (1) chemical identities of atoms allowing interpolation between elements ("ICE"), (2) degree of atomic existence enabling interpolation between atoms and vacuum ("ghost" atoms), and (3) atomic positions in higher-dimensional spaces (4-6 dimensions). These additional degrees of freedom, incorporated through a machine-learning model trained using density functional theory energies and forces, enhance global optimization by enabling circumvention of energy barriers otherwise encountered in conventional energy landscapes [8].

This approach employs a Bayesian search strategy within a Gaussian process framework, where the atomic structure representation generalizes distance and angle-distribution fingerprints to arbitrarily many spatial dimensions. The representation includes variables qᵢ,ₑ representing the degree to which atom i exists with chemical element e, restricted to the interval [0,1], with constraints ensuring conservation of elemental composition. This method has demonstrated effectiveness for clusters and periodic systems with simultaneous optimization of atomic coordinates and unit cell vectors, successfully determining structures of complex systems such as dual atom catalysts consisting of Fe-Co pairs embedded in nitrogen-doped graphene [8].

Deep Active Optimization Frameworks

For complex, high-dimensional optimization problems with limited data availability, Deep Active Optimization with Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (DANTE) represents a significant advancement. This pipeline utilizes a deep neural surrogate model iteratively to identify optimal solutions while introducing mechanisms to avoid local optima, thereby minimizing required samples. DANTE excels across varied real-world systems, outperforming existing algorithms in problems with up to 2,000 dimensions—far beyond the ~100-dimension limitation of conventional approaches—while requiring considerably less data [14].

The key innovation in DANTE is its Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (NTE), which optimizes exploration-exploitation trade-offs through visitation counts rather than uncertainty estimates. NTE employs two critical mechanisms: (1) conditional selection, which prevents value deterioration by maintaining search focus on promising regions, and (2) local backpropagation, which updates only visitation data between root and selected leaf nodes, preventing irrelevant nodes from influencing decisions and enabling escape from local optima. When tested on resource-intensive, high-dimensional, noisy complex tasks such as alloy design and peptide binder design, DANTE identified superior candidates with 9-33% improvements while requiring fewer data points than state-of-the-art methods [14].

Quantum Chemistry and Machine Learning Integration

Quantum Chemical Methods

Quantum chemistry provides the theoretical foundation for molecular modeling, offering rigorous frameworks for understanding molecular structure, reactivity, and properties at the atomic level. Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as a widely used approach due to its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy, employing exchange-correlation functionals to incorporate electron correlation effects. Recent enhancements to DFT include range-separated and double-hybrid functionals and empirical dispersion corrections (DFT-D3, DFT-D4), which have extended applicability to non-covalent systems, transition states, and electronically excited configurations relevant to catalysis and photochemistry [15].

More accurate but computationally demanding post-Hartree-Fock methods, particularly Coupled Cluster with Single, Double, and perturbative Triple excitations (CCSD(T)), provide benchmark accuracy for molecular properties but remain limited to small or medium-sized molecules due to steep scaling with system size. Fragment-based and multi-scale quantum mechanical techniques such as the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) approach and ONIOM offer practical strategies for large systems by enabling localized quantum treatments of subsystems within broader classical environments. These have proven especially valuable for modeling enzymatic reactions, ligand binding, and solvation phenomena where both quantum detail and large-scale context are essential [15].

Machine Learning Potentials and Datasets

The integration of machine learning with quantum chemistry has enabled development of machine-learning interatomic potentials that approximate quantum mechanical potential energy surfaces with significantly reduced computational cost. These ML potentials leverage various architectures including Gaussian processes, kernel regression, and neural networks, with recent advances yielding "universal" interatomic potentials applicable to broad classes of materials with different chemical compositions [8]. A critical enabling development has been the creation of large-scale datasets such as the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset, comprising over 100 million DFT calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, representing billions of CPU core-hours of compute [16].

OMol25 uniquely blends elemental, chemical, and structural diversity across 83 elements, incorporating a wide range of intra- and intermolecular interactions, explicit solvation, variable charge/spin, conformers, and reactive structures. The dataset includes approximately 83 million unique molecular systems covering small molecules, biomolecules, metal complexes, and electrolytes, with systems of up to 350 atoms—significantly expanding the size range typically included in DFT datasets. Such comprehensive datasets facilitate training of next-generation ML models that deliver quantum chemical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling high-throughput, high-accuracy molecular screening campaigns [16].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Molecular Structure Optimization

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Accuracy Level | Computational Scaling | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry | CCSD(T), DFT, MP2 | High to benchmark | O(N⁴) to O(eⁿ) | Small molecules, benchmark accuracy |

| Molecular Mechanics | AMBER, CHARMM, YAMBER3 | Medium | O(N²) | Large systems, molecular dynamics |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Gaussian processes, neural networks | Medium to high | O(N) to O(N²) | Large-scale screening, dynamics |

| Global Optimization | DANTE, Bayesian optimization | Varies with surrogate | O(N²) to O(N³) | Complex landscapes, limited data |

| Multi-scale Methods | QM/MM, FMO, ONIOM | Medium to high | O(N) to O(N³) | Enzymatic reactions, solvation effects |

Application Notes: Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Hybrid Dimensionality Reduction for Molecular Datasets

Purpose: To reduce dimensionality of high-dimensional molecular data while preserving both global and local structural relationships for downstream machine learning applications.

Materials and Computational Environment:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with minimum 64 GB RAM and multi-core processors

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, PyTorch/TensorFlow, and specialized DR libraries

- Data: Pre-processed molecular feature matrix (samples × features)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize features to zero mean and unit variance

- Handle missing values through imputation or removal

- Apply noise reduction filters if working with noisy experimental data

Initial Linear Projection:

- Apply PCA to capture global variance structure

- Retain sufficient components to explain >95% variance

- Validate component selection via scree plot analysis

Nonlinear Feature Refinement:

- Initialize RBM with adaptive graph regularization

- Construct similarity-based neighborhood graphs using k-NN (k=15)

- Train RBM with graph regularization term penalizing dissimilar representations for similar inputs

- Dynamically update edge weights based on reconstruction errors during training

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Project data through trained RBM to obtain final reduced representations

- Validate preservation of both global (via variance metrics) and local (via neighborhood retention) structures

Downstream Application:

- Utilize reduced representations for classification, regression, or visualization tasks

- Compare performance against standalone DR methods for validation

Troubleshooting:

- Poor local structure preservation: Increase k in k-NN graph construction

- Training instability: Adjust learning rate schedule or regularization strength

- Overfitting: Implement early stopping based on reconstruction loss

Diagram 1: Hybrid DR workflow combining PCA and RBM

Protocol: Deep Active Optimization for Molecular Design

Purpose: To identify optimal molecular configurations in high-dimensional spaces with limited data availability using the DANTE framework.

Materials and Computational Environment:

- Hardware: GPU-accelerated computing node (minimum 16 GB VRAM)

- Software: Custom DANTE implementation, deep learning framework (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- Initial Data: Small labeled dataset (100-200 samples) of molecular structures with target properties

Procedure:

- Initial Surrogate Model Training:

- Train deep neural network on initial molecular dataset

- Use appropriate molecular representations (fingerprints, graph neural networks, etc.)

- Validate model performance via cross-validation

Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration:

- Initialize search tree with root node representing current best solution

- Perform conditional selection based on Data-driven Upper Confidence Bound (DUCB)

- Execute stochastic rollout through feature space variations

- Apply local backpropagation to update visitation counts between root and selected nodes

Candidate Evaluation and Iteration:

- Select top candidates based on DUCB values

- Evaluate candidates using validation source (DFT, experiments, etc.)

- Add newly labeled data to training set

- Retrain surrogate model with expanded dataset

Convergence Checking:

- Monitor improvement in optimal solution quality over iterations

- Terminate when improvement falls below threshold or computational budget exhausted

Optimization Parameters:

- Stopping criterion: <1% improvement over 10 consecutive iterations

- Batch size: 5-20 candidates per iteration

- Tree depth: Adapted to molecular complexity and dimensionality

Troubleshooting:

- Premature convergence: Increase stochastic variation in rollout phase

- Poor surrogate accuracy: Increase initial training data or adjust network architecture

- Memory limitations: Reduce tree depth or batch size

Diagram 2: DANTE active optimization workflow

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Data Resource | Provides DFT calculations for ~83M molecular systems | Training ML potentials, benchmark studies |

| DANTE Framework | Software Algorithm | Deep active optimization for high-dimensional problems | Molecular design with limited data |

| SCAGE Architecture | Deep Learning Model | Self-conformation-aware molecular property prediction | Drug discovery, activity cliff prediction |

| YASARA Molecular Dynamics | Simulation Software | Molecular dynamics with YAMBER3 force field | Protein-ligand simulations, membrane systems |

| Quantum Chemistry Codes | Computational Method | DFT, CCSD(T) calculations for electronic structure | Benchmark accuracy, small molecule studies |

| Hyperdimensional Computing | Emerging Paradigm | Brain-inspired computing with high-dimensional vectors | Resource-constrained edge devices |

The integration of advanced dimensionality reduction techniques with machine learning-enabled global optimization algorithms represents a transformative development in molecular modeling's capacity to navigate high-dimensional configuration spaces. By combining the complementary strengths of linear and nonlinear DR methods through hybrid frameworks, researchers can now preserve both global molecular structure and local neighborhood relationships while significantly reducing computational requirements. Similarly, deep active optimization approaches like DANTE demonstrate remarkable capability to identify optimal molecular configurations in spaces of up to 2,000 dimensions using limited data—overcoming fundamental limitations of traditional optimization methods.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas: deeper theoretical understanding of high-dimensional molecular spaces, improved hybrid models that seamlessly integrate physical principles with data-driven approaches, and more scalable computational frameworks that leverage specialized hardware architectures. The growing integration of artificial intelligence across all aspects of molecular modeling—from automated feature extraction to active optimization—promises to further accelerate the discovery of novel molecular structures with tailored properties for applications spanning drug development, materials science, and renewable energy technologies.

Algorithmic Toolkit: Key Global Optimization Methods and Their Drug Discovery Applications

Global optimization, the process of finding the input values to an objective function that results in the lowest or highest possible output, is a cornerstone of scientific computing. In molecular structure research, this translates to identifying atomic configurations with the lowest potential energy, which correspond to the most stable and biologically relevant structures. The potential energy surfaces of molecules, particularly large and flexible ones, are characterized by high dimensionality, non-convexity, and a multitude of local minima, making them exceptionally challenging for traditional gradient-based optimization methods [3].

Nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for navigating such complex landscapes. These population-based algorithms do not require gradient information and are less likely to become trapped in local optima, making them ideally suited for global optimization problems in chemistry and drug development. This article focuses on two prominent algorithms—the Snake Optimizer (SO) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)—and their enhanced variants, detailing their mechanisms, improvements, and specific application protocols for molecular research.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Enhancements

The Snake Optimizer (SO)

The Snake Optimizer is a novel metaheuristic algorithm proposed in 2022, inspired by the foraging and reproductive behaviors of snakes. Its population is divided into male and female groups. The algorithm's behavior is governed by two key environmental factors: food quantity (Q) and temperature (Temp). If food is scarce (Q < 0.25), the snakes enter an exploration phase, searching the environment randomly. When food is plentiful, the algorithm enters an exploitation phase, where the snakes' behavior depends on the temperature. A high temperature prompts them to move toward the best food source, while a low temperature triggers either combat (among males) or mating (between males and females) behaviors [17].

Despite its innovative mechanics, the standard SO algorithm suffers from limitations, including random population initialization, slow convergence speed, low solution accuracy, and a tendency to converge to local optima [18] [19]. These shortcomings have spurred the development of numerous improved variants.

The Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO)

Particle Swarm Optimization is a well-established metaheuristic inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling. Each "particle" in the swarm represents a potential solution and navigates the search space by adjusting its trajectory based on its own experience (pbest) and the experience of its neighbors (gbest). A key component of PSO is the velocity update rule, which determines how particles move.

Enhanced Variants and Hybrid Algorithms

To overcome the limitations of the base algorithms, researchers have developed enhanced versions, including a notable hybrid that combines the strengths of SO and PSO.

SO-PSO Hybrid: This hybrid integrates the velocity vector from PSO into the Snake Optimizer. The PSO component improves exploration, accelerates convergence, and helps avoid local optima, while the SO component provides a robust search framework. According to comprehensive benchmarking on the CEC-2017 test suite and seven engineering problems, the SO-PSO hybrid ranked first (1.62) in the Friedman test, outperforming standard SO (3.28), PSO (5.91), and other contemporary metaheuristics like WOA and GWO [20].

Table 1: Summary of Key Snake Optimizer Variants and Their Improvement Strategies.

| Variant Name | Core Improvement Strategies | Reported Advantages | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTHSO [18] | Tent chaotic mapping; Quasi-opposite learning; Adaptive t-distribution mixed mutation. | Improved convergence speed & accuracy; Better escape from local optima. | General function optimization; Energy storage system capacity optimization. |

| ISO [19] | Sobol sequence initialization; Fusion of RIME algorithm; Lens reverse learning; Lévy flight. | Superior convergence speed, stability, and global optimization capability. | UAV/Robot path planning; Wireless sensor networks; Pressure vessel design. |

| SO-PSO [20] | Integration of PSO's velocity vector into the SO framework. | Enhanced exploration; Faster convergence; Avoids local optima. | Continuous numerical optimization; Real-world engineering problems. |

| EMSO [21] | New food & temperature mechanisms; Differential evolution & sine-cosine search; Dynamic opposite learning. | Better balance of exploration/exploitation; Avoids premature convergence. | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling. |

| SNDSO [17] | Sobol sequence initialization; Nonlinear factors based on arctangent; Different learning strategies. | Improved performance on discretized, high-dimensional, and multi-constraint problems. | Feature selection; Engineering design problems. |

Application Notes for Molecular Structure Research

Global optimization methods are critical for predicting molecular structures, including conformations, crystal polymorphs, and reaction pathways. These approaches typically follow a two-step process: a global search to identify candidate structures, followed by local refinement to determine the most stable configurations [3]. Metaheuristics like SO and PSO excel in the global search phase.

Application Protocol: Molecular Conformer Search

This protocol outlines the use of an improved SO algorithm for finding the low-energy conformers of a flexible drug-like molecule.

1. Problem Definition and Parameterization

- Objective Function: The potential energy of the molecular system, calculated using a force field (e.g., MMFF94) or a semi-empirical quantum method (e.g., PM7).

- Decision Variables: The rotatable torsion angles within the molecule. Each torsion angle represents a dimension in the optimization problem.

- Search Space: Each torsion angle is bound between -180 and 180 degrees.

2. Algorithm Initialization

- Algorithm: Employ the EMSO [21] or SNDSO [17] variant.

- Population Size: Initialize a population of 50 candidate solutions (snakes). Each solution is a vector of randomly generated torsion angles within the defined bounds. Using a Sobol sequence [19] [17] for initialization is recommended for a more uniform distribution.

- Fitness Evaluation: For each candidate solution, generate the 3D molecular structure, minimize the energy with a quick local minimization (to relieve clashes), and then compute its final potential energy. This energy value is the fitness to be minimized.

3. Iterative Optimization

- Execute the EMSO/SNDSO iterative process, which includes phases of exploration and exploitation controlled by food quantity

Qand temperatureTemp. - In each iteration, new candidate solutions are generated. For each new solution, the energy is calculated as described in Step 2.

- The algorithm runs for a predetermined number of iterations (e.g., 1000) or until convergence (i.e., no significant improvement in the best-found solution is observed for 50 consecutive iterations).

4. Post-Processing and Analysis

- Cluster Results: Collect all unique low-energy conformers found during the search.

- Refinement: Perform high-level, local geometry optimization (e.g., using Density Functional Theory) on the most promising low-energy conformers to obtain final, accurate structures.

- Validation: Compare the predicted conformers with known experimental data (e.g., from crystal structures) or benchmark against results from other established conformer search tools.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol:

Application in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR models relate a compound's molecular structure to its biological activity. A critical step in building a robust QSAR model is the simultaneous optimization of discrete variables (feature selection) and continuous variables (model hyperparameters). The Enhanced Multi-strategy Snake Optimizer (EMSO) has been successfully applied to this joint optimization problem [21].

Key Steps in the EMSO-based QSAR Protocol:

- Problem Encoding: A single solution (snake) encodes both the selected molecular descriptors (binary string) and the hyperparameters of the machine learning model (continuous values).

- Fitness Function: The fitness is typically a function of the model's predictive accuracy (e.g., cross-validated R² or RMSE) combined with a penalty for a large number of descriptors to avoid overfitting.

- EMSO Optimization: The EMSO algorithm, with its improved mechanisms for global search and escaping local optima, is used to find the optimal combination of features and hyperparameters.

- Model Building: The final model is built using the optimized features and hyperparameters, leading to a simpler, more interpretable, and highly predictive QSAR model for environmental toxicity prediction or drug activity screening [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational "Reagents" for Metaheuristic-Driven Molecular Research.

| Item / Tool | Function / Description | Relevance to Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields (e.g., MMFF94, GAFF) | Empirical functions for calculating molecular potential energy. | Serves as the primary objective function for energy-based optimization tasks like conformer searching. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Performs ab initio and DFT calculations for highly accurate energy and property predictions. | Used for high-fidelity local refinement of candidate structures identified by the global metaheuristic search. |

| Sobol Sequence | A quasi-random number sequence for generating initial points in a hypercube. | Used in population initialization for algorithms like ISO and SNDSO to ensure uniform coverage of the search space [19] [17]. |

| Lévy Flight | A random walk process with step lengths that follow a heavy-tailed probability distribution. | Incorporated into algorithms like ISO to promote large, exploratory moves, helping to escape local minima [19]. |

| Dynamic Opposite Learning (DOL) | A strategy to generate the opposite of current solutions to explore the search space more thoroughly. | A key component in EMSO to enhance population diversity and the ability to escape local optima [21]. |

| CEC Benchmark Suites | Standardized sets of test functions (e.g., CEC-2017, CEC-2020) for evaluating optimization algorithms. | The gold standard for impartially comparing the performance of new algorithm variants against state-of-the-art methods [20] [17]. |

The relentless increase in the complexity and scale of molecular optimization problems in drug development necessitates equally advanced computational strategies. The Snake Optimizer, particularly in its enhanced and hybridized forms like EMSO, ISO, and SO-PSO, represents a significant advancement in the metaheuristic toolkit. These algorithms address critical limitations of their predecessors through sophisticated initialization, adaptive control of search behavior, and hybrid mechanisms, leading to faster convergence, higher accuracy, and superior performance on high-dimensional, multi-modal problems. When integrated into standardized protocols for molecular conformer searching or QSAR model development, these nature-inspired optimizers provide researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful, automated means to navigate vast chemical spaces and accelerate the discovery of novel molecular entities.

The accurate simulation of molecular interactions represents a cornerstone in drug discovery and materials science, as it directly informs the design of novel compounds with tailored properties. However, the global optimization of molecular structures requires navigating an exceptionally vast and complex chemical space, a task that poses immense challenges for classical computational methods. Quantum computing is emerging as a transformative paradigm to address these limitations, offering a fundamentally different approach rooted in quantum mechanics. By leveraging principles such as superposition and entanglement, quantum computers can naturally represent and simulate quantum mechanical systems, including molecular interactions at the electronic level. This capability is particularly crucial for modeling non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces—which are inherently quantum mechanical, weak, dynamic, and critically important in biological processes like protein folding and drug-receptor binding [22]. The integration of quantum computing into the computational chemist's toolbox opens new avenues for achieving unprecedented accuracy in molecular simulation, potentially revolutionizing the early stages of research and development.

Quantum Computing Fundamentals for Molecular Simulation

The Electronic Structure Problem

At its core, the simulation of a molecule involves solving the Schrödinger equation for a system of electrons and nuclei. The solution provides the molecule's wavefunction, from which all chemical properties can, in principle, be derived. This is known as the electronic structure problem. Classical computers struggle with the exact solution of this problem because the computational resources required scale exponentially with the number of electrons. While approximation methods have been developed, they often trade accuracy for computational feasibility, limiting their predictive power for complex or unknown systems [23].

Quantum computers, comprising quantum bits or qubits, are inherently suited to this challenge. A qubit can exist in a superposition of 0 and 1 states, allowing a quantum computer to represent a quantum system's wavefunction naturally. Algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) are designed to harness this capability to find the energy and properties of molecular systems [22]. The most accurate approaches achieving chemical accuracy (±1 kcal/mol) rely on quantum mechanical descriptions, but their high computational cost limits scalability on classical hardware [22].

Current Hardware Landscape and the NISQ Era

Current quantum hardware operates in the so-called Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era. NISQ devices, typically featuring tens to over a hundred qubits, are limited by qubit coherence times and significant error rates. These constraints preclude the direct execution of long, complex quantum algorithms without error correction. To overcome these limitations, the field has pivoted towards hybrid quantum-classical approaches. In these methods, a quantum computer handles the parts of the calculation that are intractable for classical machines—such as preparing and measuring complex quantum states—while a classical computer oversees the optimization process and performs complementary computations [23] [24]. This synergy defines the quantum-centric supercomputing (QCSC) paradigm, where quantum processors are integrated with classical high-performance computing (HPC) resources to solve problems currently beyond the reach of either type of computer alone [22].

Key Quantum Algorithms and Experimental Protocols

Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD)

The SQD algorithm is a powerful hybrid method that leverages quantum hardware to sample electronic configurations and classical HPC resources to diagonalize the molecular Hamiltonian in a reduced subspace [22].

Experimental Protocol: SQD for Potential Energy Surface (PES) Simulation

- Objective: To simulate the PES of a molecular dimer (e.g., water or methane dimer) to calculate the binding energy governed by non-covalent interactions.

Principle: A quantum processor samples important electronic configurations from a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that approximates the ground state of the molecule. These samples are used classically to define a subspace in which the Schrödinger equation is solved with high accuracy [22].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Active Space Selection: Use a classical method like AVAS (Automated Valence Active Space) to select a chemically relevant subset of molecular orbitals and electrons for the quantum computation [22].

- Ansatz Preparation: Prepare a quantum circuit using an ansatz, such as the Local Unitary Coupled Cluster (LUCJ), which approximates the full Unitary Coupled Cluster with Single and Double excitations (UCCSD) with reduced circuit depth [22].

- Quantum Sampling: Execute the quantum circuit on the processor (e.g., an IBM Eagle processor) and perform multiple measurements to sample the resulting electronic configurations [23] [22].

- Configuration Recovery (S-CORE): Use a classical post-processing procedure (S-CORE) to identify and correct configurations corrupted by quantum hardware noise [22].

- Classical Diagonalization: Construct the Hamiltonian matrix within the subspace spanned by the recovered configurations. Use distributed classical HPC resources to diagonalize this matrix and obtain the total energy [22].

- Energy Extrapolation: Employ extrapolation techniques based on Hamiltonian variance to estimate the exact ground-state energy from results obtained with varying numbers of sampled configurations [22].

Key Quantitative Results:

- A 2025 study simulated the PES of water and methane dimers using 27- and 36-qubit circuits, respectively [22].

- The SQD-computed binding energies registered deviations within 1.000 kcal/mol from the classical gold-standard CCSD(T) method, achieving chemical accuracy [22].

- For a methane dimer system with 16 electrons and 24 orbitals, the LUCJ ansatz execution took approximately 229 seconds on the

ibm_kyivprocessor [22].

Density Matrix Embedding Theory with SQD (DMET-SQD)

For larger molecules, a direct quantum simulation may still be prohibitive. DMET-SQD is a fragmentation-based hybrid approach that breaks the molecule into smaller, tractable subsystems.

Experimental Protocol: DMET-SQD for Complex Molecule Simulation

- Objective: To simulate the electronic structure and relative energies of conformers in biologically relevant molecules (e.g., cyclohexane) using current quantum devices [23].

Principle: The global molecule is partitioned into smaller fragments. Each fragment is embedded in a mean-field potential representing the rest of the molecule. The quantum computer then simulates the electronic structure of each individual fragment using the SQD method. The process is iterated until self-consistency is achieved between the fragment solutions and the global mean-field description [23].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Molecular Fragmentation: Partition the target molecule into smaller, chemically logical fragments.

- Initial Mean-Field Calculation: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock calculation for the entire molecule to generate an initial approximate electronic environment.

- Quantum Fragment Simulation: For each fragment:

- a. Construct the embedded fragment Hamiltonian.

- b. Use the SQD protocol (as described in Section 3.1) on a quantum processor (e.g., using 27-32 qubits) to compute the accurate ground state of the fragment [23].

- Self-Consistent Loop: Use the quantum solution for the fragments to update the mean-field potential of the environment. Iterate steps 3 and 4 until energy and electron number converge.

- Property Calculation: Assemble the total energy of the molecule from the converged fragment energies.

Key Quantitative Results:

- A study applied DMET-SQD to simulate the chair, boat, half-chair, and twist-boat conformers of cyclohexane [23].

- The method produced energy differences between conformers within 1 kcal/mol of classical benchmarks, preserving the correct energy ordering [23].

- This approach demonstrated the feasibility of simulating chemically relevant molecules without requiring thousands of qubits, a significant step toward practical application [23].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a typical hybrid quantum-classical simulation, such as the SQD method:

Performance Data and Benchmarking

The performance of quantum-centric simulation methods is benchmarked against established classical computational chemistry methods. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Benchmarking Quantum-Centric Molecular Simulations Against Classical Methods

| Molecular System | Quantum Method (Qubits Used) | Classical Benchmark Method | Reported Accuracy (Deviation from Benchmark) | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Dimer [22] | SQD (27 qubits) | CCSD(T) | Within 1.000 kcal/mol | Achieved chemical accuracy for hydrogen bonding interaction. |

| Methane Dimer [22] | SQD (36 qubits) | CCSD(T) | Within 1.000 kcal/mol | Achieved chemical accuracy for dispersion interaction. |

| Methane Dimer [22] | SQD (54 qubits) | HCI / CCSD(T) | Systematically improvable with sampling | Demonstrated scalability to larger qubit counts. |

| Cyclohexane Conformers [23] | DMET-SQD (27-32 qubits) | HCI / CCSD(T) | Within 1 kcal/mol | Correctly ordered conformer energies using a fragment-based approach. |

| Hydrogen Ring (18 atoms) [23] | DMET-SQD (27-32 qubits) | Heat-Bath CI (HCI) | Minimal deviation | Accurately handled strong electron correlation effects. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

In the context of quantum computational chemistry, "research reagents" refer to the essential software, hardware, and methodological components required to conduct experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Molecular Simulation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Quantum Processor (e.g., IBM Eagle, Google Willow [25]) | Hardware | The physical quantum device that executes the quantum circuits; performs the sampling of electronic configurations. |

| Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) Ansatz | Algorithm | A parameterized quantum circuit that generates an approximation of the molecular wavefunction, serving as the starting point for sampling. |

| Local UCC (LUCJ) [22] | Algorithm | An efficient approximation of UCCSD that reduces quantum circuit depth, making it more practical for NISQ devices. |

| Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) [22] | Software/Algorithm | The core hybrid algorithm that uses quantum samples and classical diagonalization to solve the electronic structure problem. |

| Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) [23] | Software/Algorithm | A fragmentation method that enables the simulation of large molecules by breaking them into smaller, quantum-tractable subsystems. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques (e.g., gate twirling, dynamical decoupling [23]) | Software/Methodology | A suite of techniques applied to mitigate the effect of noise on current quantum hardware without the overhead of full quantum error correction. |

| Quantum-Centric Supercomputing (QCSC) Architecture [22] | Workflow/Infrastructure | The computational paradigm that integrates quantum processors with classical HPC resources for distributed and amplified computation. |

Error Correction and the Path to Fault Tolerance

The accuracy of quantum simulations is intrinsically linked to the error rates of the physical hardware. Quantum Error Correction (QEC) is essential for bridging this gap, encoding logical qubits across multiple physical qubits to detect and correct errors in real-time. Recent breakthroughs have moved beyond the well-studied surface code to demonstrate more efficient codes like the color code [26] [25] [27].

Color Code Protocol and Performance

- Objective: To implement a QEC code that offers more efficient logical operations and reduced physical qubit overhead compared to the surface code.

- Protocol: Physical qubits are arranged in a hexagonal tiling within a triangular patch. Parity-check measurements (stabilizers) are performed cyclically to detect errors without collapsing the logical quantum state. A classical decoding algorithm then interprets the measurement results to identify and correct the most likely errors [25].

- Key Results:

- Error Suppression: Scaling the color code distance from 3 to 5 suppressed logical errors by a factor of 1.56 [26] [25].

- Fast Logical Operations: Transversal Clifford gates (a type of logical operation) were demonstrated with an added error of only 0.0027, significantly lower than an idling error correction cycle [25].

- Magic State Injection: A critical resource for universal quantum computation was demonstrated with fidelities exceeding 99% (with 75% data retention) [25].

- Logical Entanglement: Lattice surgery techniques were used to teleport logical states between two color code logical qubits with fidelities between 86.5% and 90.7% [25].

The structure and logical relationships within a color code quantum error correction patch can be visualized as follows:

Integration with Global Optimization Frameworks

Quantum molecular simulations do not operate in isolation but serve as a highly accurate energy evaluation engine within broader global optimization algorithms used for molecular structure research. For instance, in a genetic algorithm for drug molecule optimization, a population of candidate molecules is evolved over generations. The critical step of evaluating the fitness of each candidate—often a measure of binding affinity or stability—can be augmented or replaced by a quantum simulation like SQD or DMET-SQD to provide a more reliable and physically grounded score than classical force fields or machine learning models trained on limited data [28] [29]. This creates a powerful hybrid optimization pipeline: the quantum computer handles the complex, high-accuracy electronic structure calculations for key intermediates or promising candidates, while the classical global optimization algorithm efficiently navigates the vast chemical space. This approach mitigates the data dependency and potential overfitting of purely AI-driven models, enabling the exploration of novel chemical scaffolds with a higher degree of confidence in the predicted properties [30] [24].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming the landscape of drug discovery and development. These technologies are enabling a paradigm shift from traditional, labor-intensive methods to a new era of data-driven, computationally empowered research. This is particularly impactful in the realms of predictive modeling for biomolecular interactions and de novo drug design, where AI helps navigate the vast complexity of chemical and biological space with unprecedented speed and precision [31] [32].

This transformation is crucial within the context of global optimization algorithms for molecular structure research. The challenge of finding optimal molecular structures with desired properties and functions represents a high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problem across an astronomically large search space. AI and ML models, trained on vast biological datasets, are emerging as powerful tools to efficiently explore this space, effectively acting as sophisticated objective functions that map sequences to structures and functions, thereby guiding global optimization efforts toward promising regions [33].

Quantitative Benchmarks of AI Models in Drug Discovery

The performance of AI models is quantified using key metrics that benchmark their predictive accuracy and utility in drug discovery pipelines. The tables below summarize quantitative data for recent, state-of-the-art AI models.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Key AI Models in Structure and Affinity Prediction

| Model Name | Primary Function | Key Performance Metric | Reported Performance | Compute Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 [34] | Biomolecular complex structure prediction | Accuracy improvement on protein-ligand interactions | ≥50% improvement vs. prior methods | Not Specified |

| Boltz-2 [34] [35] | Protein-ligand structure & binding affinity prediction | Correlation with experimental binding data | ~0.6 correlation with experiment | ~20 seconds |

| Hermes [35] | Small molecule-protein binding prediction | Predictive performance on internal benchmarks | Improved performance vs. competitive AI models | 200-500x faster than Boltz-2 |

| Latent-X [35] | De novo protein design | Experimental binding affinity | Picomolar range affinities | Not Specified |

Table 2: Impact of AI on Preclinical Drug Discovery Timelines

| Metric | Traditional Workflow | AI-Accelerated Workflow | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical Project Timeline | ~42 months | ~18 months | [34] |

| Compounds Synthesized | Thousands | Few hundred | [34] |

| De Novo Drug Candidate Identification | 4-5 years | ~18 months | [32] [36] |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven de Novo Design

The following section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the field, outlining the workflows that translate AI predictions into validated biological results.

Protocol 1: AI-Driven de Novo Design of a Small Molecule Inhibitor

This protocol details the steps for designing a novel small molecule inhibitor targeting a specific protein, based on published approaches [32] [36] [37].

1. Target Selection and Featurization:

- Input: Select a target protein (e.g., an immune checkpoint like PD-L1).

- Feature Encoding: Represent the target's binding pocket using 3D atomic coordinates (from PDB or an AlphaFold-predicted structure). Encode the physicochemical properties of the pocket (e.g., hydrophobicity, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, electrostatic potential).

2. Generative Molecular Design:

- Model Application: Employ a generative AI model, such as a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) or Variational Autoencoder (VAE), trained on chemical libraries (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC).

- Generation: The model generates novel molecular structures (represented as SMILES strings or 3D structures) optimized for complementary shape and chemical complementarity to the target pocket.

- Output: A library of 1,000 - 100,000 generated candidate molecules.

3. In Silico Validation and Filtering:

- Property Prediction: Use ML models (e.g., QSPR models) to predict key ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties for all generated candidates. Filter out compounds with poor predicted pharmacokinetics or toxicity.

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Employ a structure-based binding affinity predictor, such as Boltz-2, to rank the filtered compounds by predicted binding strength (e.g., IC50, Kd).

- Selection: Select the top 10-50 candidate molecules for synthesis based on a composite score of binding affinity and drug-like properties.

4. Synthesis and Experimental Validation:

- Chemical Synthesis: Synthesize the selected candidates using medicinal chemistry routes.

- In Vitro Assay: Test synthesized compounds in a biochemical assay (e.g., fluorescence polarization, surface plasmon resonance) to measure experimental binding affinity against the purified target protein.

- Functional Assay: Progress compounds with confirmed binding into a cell-based assay (e.g., a T-cell activation assay for an immune checkpoint inhibitor) to confirm functional activity.

Protocol 2: De Novo Design of a Protein Binder

This protocol outlines the process for designing a novel mini-protein that binds to a specific therapeutic target with high affinity, as demonstrated by recent platforms [33] [34] [35].

1. Target Scaffolding and Motif Specification:

- Input: Provide the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from PDB or AlphaFold 3).

- Scaffold Definition: Specify the desired structural motif for the binder (e.g., alpha-helical bundle, beta-sheet, cyclic peptide) and any known contact residues.

2. Structure-Based Sequence Generation:

- Model Application: Use a de novo protein design model like RFdiffusion, AlphaProteo, or Latent-X. These models use diffusion or other generative processes to create a backbone structure that sterically and chemically complements the target surface.

- Sequence Design: Pass the generated backbone to a sequence-design network like ProteinMPNN, which predicts an amino acid sequence that will fold into the desired structure.

- Output: A library of 100 - 10,000 designed protein sequences and their predicted structures in complex with the target.

3. Computational Filtering and Ranking:

- Folding Validation: Refold the designed sequences using a structure predictor like AlphaFold 2/3 or ESMFold to check for structural consensus between the designed and refolded states. Discard designs with low confidence or poor structural agreement.

- Interface Analysis: Calculate the binding energy (e.g., using dDG calculations) of the predicted complex. Rank designs based on predicted binding strength and interface quality.

- Developability Assessment: Predict solubility, stability, and potential immunogenicity using specialized ML tools. Select the top 20-100 designs for experimental testing.

4. Experimental Characterization:

- Gene Synthesis and Expression: Code the selected DNA sequences for the designed proteins, and express them in a suitable system (e.g., E. coli).

- Affinity Measurement: Purify the expressed proteins and measure binding affinity to the target using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI). Designs like those from Latent-X have achieved picomolar affinities by testing only 30-100 candidates [35].

- Structural Validation: For high-affinity binders, determine the experimental structure of the complex using X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to validate the AI-predicted binding mode.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflows and signaling pathways central to AI-driven drug design.

AI-Driven de Novo Drug Design Workflow

Diagram Title: AI de Novo Drug Design Workflow

AI-Augmented Global Optimization in Molecular Research

Diagram Title: AI-Augmented Global Optimization Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential computational and experimental resources for implementing the protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications / Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server [34] | Predicts 3D structures of proteins and biomolecular complexes. | Free online server for non-commercial use; predicts proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, ions. |

| Boltz-2 Model [34] [35] | Open-source model for predicting protein-ligand structure and binding affinity. | Available under MIT license; runs on a single GPU in ~20 seconds. |

| RFdiffusion / ProteinMPNN [34] | Software for de novo protein backbone generation (RFdiffusion) and sequence design (ProteinMPNN). | Open-source tools from the Baker Lab; available on GitHub. |

| SAIR Database [35] | Open-access repository of computationally folded protein-ligand structures with affinity data. | Contains >1 million unique protein-ligand pairs; sourced from ChEMBL/BindingDB. |

| ChEMBL / BindingDB [37] [35] | Public databases of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and binding affinities. | Used for training generative models and validating predictions. |

| Expression System (E. coli) | For producing designed protein binders. | Requires gene synthesis, transformation, and protein purification reagents. |

| SPR/BLI Instrument | For label-free, quantitative measurement of binding kinetics (Kon, Koff, KD). | Instruments from vendors like Cytiva (Biacore) or Sartorius (Octet). |

The accurate prediction of ligand-protein binding affinity and the determination of optimal protein folds represent two of the most computationally intensive challenges in structural biology and drug discovery. Both problems are fundamentally global optimization challenges on high-dimensional, complex energy landscapes. Recent advances in machine learning, quantum computing, and novel algorithms have begun to transform our approach to these problems, moving from approximate solutions to increasingly precise predictions. This case study examines contemporary breakthroughs that address critical bottlenecks in molecular structure research through innovative optimization frameworks, highlighting practical applications, experimental protocols, and quantitative performance comparisons essential for research implementation.

Ligand-Protein Binding Affinity Prediction

The Data Leakage Problem and Its Resolution