Comparative Analysis of Spectral Assignment Methods: From Foundational Principles to AI-Enhanced Applications in Biomedical Research

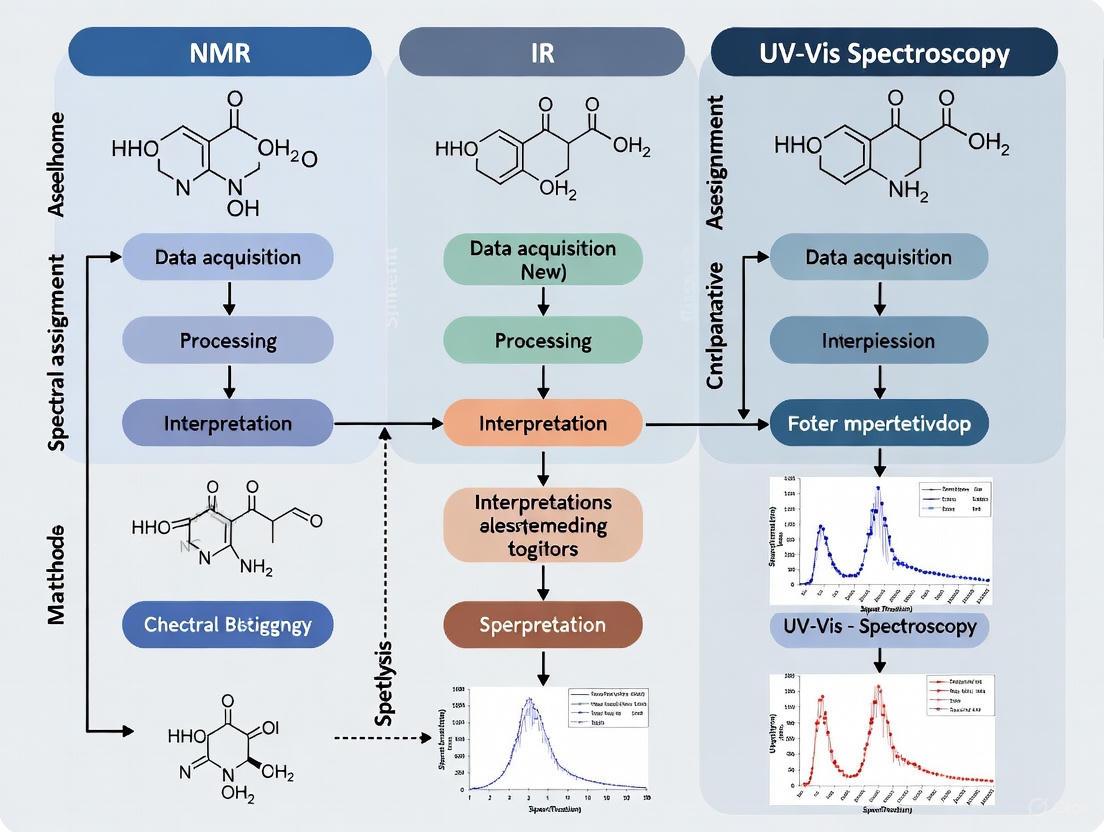

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of spectral assignment methodologies, tracing their evolution from foundational principles to cutting-edge AI-integrated applications.

Comparative Analysis of Spectral Assignment Methods: From Foundational Principles to AI-Enhanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of spectral assignment methodologies, tracing their evolution from foundational principles to cutting-edge AI-integrated applications. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core mechanisms of techniques like Raman spectroscopy and mass spectrometry, evaluates traditional versus machine learning-driven spectral interpretation, and addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world data. The analysis further establishes rigorous validation frameworks and performance benchmarks across biomedical applications, including drug discovery, proteomics, and clinical diagnostics, synthesizing key insights to guide method selection and future technological development.

Core Principles and the Evolution of Spectral Analysis Technologies

Spectral assignment is the computational process of linking an experimentally measured molecular spectrum to a specific chemical structure. Within this field, molecular fingerprinting has emerged as a powerful methodology for converting complex spectral data into a structured, machine-readable format that encodes key structural or physicochemical properties of a molecule [1]. These fingerprints are typically represented as bit vectors where each bit indicates the presence or absence of a particular molecular feature [1]. The core premise of spectral assignment via fingerprinting is that similar molecular structures will produce similar spectral signatures, and by extension, similar fingerprint representations. This approach has become indispensable in various scientific domains, from drug discovery and metabolite identification to sensory science, where it helps researchers bridge the gap between analytical measurements and molecular identity [2] [3].

The chemical space is astronomically large, with estimates suggesting over 10^60 different drug-like molecules exist [4]. This vastness makes experimental testing of all interesting compounds impossible, creating a critical need for computational methods like fingerprinting to prioritize molecules for further investigation [4]. As spectroscopic techniques continue to generate increasingly complex datasets, the role of molecular fingerprints in enabling efficient spectral interpretation and chemical space exploration has become more crucial than ever [5] [1].

Categories of Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints can be categorized based on the type of molecular information they capture and their generation methodology. Understanding these categories is essential for selecting the appropriate fingerprint for a specific spectral assignment task.

Table 1: Major Categories of Molecular Fingerprints

| Category | Description | Representative Examples | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path-Based | Generates features by analyzing paths through the molecular graph | Depth First Search (DFS), Atom Pair (AP) [1] | General similarity searching, structural analog identification |

| Circular | Constructs fragment identifiers dynamically from molecular graph using neighborhood radii | Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP), Functional Class Fingerprints (FCFP) [1] | Structure-activity relationship modeling, bioactivity prediction |

| Substructure-Based | Uses predefined structural motifs or patterns | MACCS, PUBCHEM [1] | Rapid screening for specific functional groups or pharmacophores |

| Pharmacophore | Encodes potential interaction capabilities rather than pure structure | Pharmacophore Pairs (PH2), Pharmacophore Triplets (PH3) [1] | Virtual screening, interaction potential assessment |

| String-Based | Operates on SMILES string representations rather than molecular graphs | LINGO, MinHashed (MHFP), MinHashed Atom Pair (MAP4) [1] | Large-scale chemical database searching, similarity assessment |

Different fingerprint categories provide fundamentally different views of the chemical space, which can lead to substantial differences in pairwise similarity assessments and overall performance in spectral assignment tasks [1]. For instance, while circular fingerprints like ECFP are often considered the de-facto standard for encoding drug-like compounds, research has shown that other fingerprint types can match or even outperform them for specific applications such as natural product characterization [1].

Performance Comparison of Fingerprinting Methods

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking studies have evaluated various fingerprinting approaches across multiple applications. Performance is typically assessed using metrics such as Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), accuracy, precision, and recall [3] [4]. The choice of evaluation metric is crucial, as each emphasizes different aspects of predictive performance—AUROC measures overall discrimination ability, while AUPRC is more informative for imbalanced datasets where active compounds are rare [3].

Comparative Performance in Odor Prediction

In a comprehensive 2025 study examining the relationship between molecular structure and odor perception, researchers benchmarked multiple fingerprint types across various machine learning algorithms [3]. The study utilized a curated dataset of 8,681 compounds from ten expert sources and evaluated functional group fingerprints, classical molecular descriptors, and Morgan structural fingerprints with Random Forest, XGBoost, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine algorithms [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Fingerprint and Algorithm Combinations for Odor Prediction

| Feature Set | Algorithm | AUROC | AUPRC | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | XGBoost | 0.828 | 0.237 | 97.8 | 41.9 | 16.3 |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | LightGBM | 0.810 | 0.228 | - | - | - |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | Random Forest | 0.784 | 0.216 | - | - | - |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | XGBoost | 0.802 | 0.200 | - | - | - |

| Functional Group (FG) | XGBoost | 0.753 | 0.088 | - | - | - |

The results clearly demonstrate the superior performance of Morgan fingerprints combined with the XGBoost algorithm, achieving the highest discrimination with an AUROC of 0.828 and AUPRC of 0.237 [3]. This configuration consistently outperformed descriptor-based models, highlighting the superior representational capacity of topological fingerprints for capturing complex olfactory cues [3].

Performance in Bioactivity Prediction

The FP-MAP study provided additional insights into fingerprint performance across multiple biological targets [4]. This extensive library of fingerprint-based prediction tools evaluated approximately 4,000 classification and regression models using 12 different molecular fingerprints across diverse bioactivity datasets [4]. The best-performing models achieved test set AUC values ranging from 0.62 to 0.99, demonstrating the context-dependent nature of fingerprint performance [4]. Similarly, a 2024 benchmarking study on natural products revealed that while circular fingerprints generally perform well, the optimal fingerprint choice depends on the specific characteristics of the chemical space being investigated [1].

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Fingerprinting

Standard Workflow for MS/MS-Based Molecular Fingerprint Prediction

The experimental protocol for deep learning-based molecular fingerprint prediction from MS/MS spectra involves multiple carefully orchestrated steps [2]:

Data Acquisition and Curation: MS/MS spectra are collected from reference databases such as NIST, MassBank of North America (MoNA), or Human Metabolome Database (HMDB). Each spectrum is annotated with reference compound information including metabolite ID, molecular formula, InChIKey, SMILES, precursor m/z, adduct, ionization mode, and collision energy [2].

Spectral Preprocessing:

- Peak intensity scaling to relative intensities between 0 and 100

- Separation of spectra by ionization mode (positive/negative)

- Filtering of spectra with no or multiple precursor masses

- Removal of spectra with fewer than five peaks

- Elimination of peaks outside the mass range of 100-1010 Dalton

- Selection of top 20 peaks by relative intensity [2]

Spectral Binning and Feature Selection:

- Mapping selected peaks into bins of 0.01 Dalton size

- Summing intensity values within each bin to produce binned intensity vectors

- Filtering bins present in less than 0.1% of training spectra

- This process typically reduces ~91,000 potential bins to approximately 2,000 relevant spectral features [2]

Molecular Fingerprint Calculation:

- Generation of molecular fingerprints from SMILES strings using tools like PyFingerprint or OpenBabel

- Transformation of fingerprints from predefined structure libraries (FP3, FP4, PubChem, MACCS, Klekota-Roth) into binary vectors

- Filtering of non-informative fingerprints (those appearing as all 1s or 0s across all compounds)

- Condensation of redundant fingerprint vectors [2]

Model Training and Validation:

- Training of deep learning models (Deep Neural Networks, Convolutional Neural Networks, Recurrent Neural Networks) to predict molecular fingerprints from binned spectral data

- Implementation of structure-disjoint evaluation to ensure no overlap between training and testing compounds

- Use of benchmark datasets like CASMI for performance evaluation [2]

Experimental Protocol for Odor Prediction Benchmarking

The 2025 study on odor prediction employed a different methodological approach focused on structural fingerprints rather than spectral data [3]:

Dataset Curation:

- Unification of ten expert-curated olfactory datasets keyed by PubChem CID

- Retrieval of canonical SMILES via PubChem's PUG-REST API

- Standardization of odor descriptors to a controlled vocabulary of 201 labels

- Expert-guided resolution of inconsistencies in descriptor terminology [3]

Feature Extraction:

- Functional Group Features: Generated by detecting predefined substructures using SMARTS patterns

- Molecular Descriptors: Calculated using RDKit, including molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, topological polar surface area, logP, rotatable bonds, heavy atom count, and ring count

- Morgan Fingerprints: Derived from MolBlock representations generated from SMILES strings and optimized using universal force field algorithm [3]

Model Development:

- Implementation of multi-label classification to capture overlapping odor characteristics

- Training of separate one-vs-all classifiers for each odor label

- Stratified five-fold cross-validation with 80:20 train:test split

- Benchmarking of Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM algorithms [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Fingerprinting

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIST MS/MS Library | Spectral Database | Reference spectra for compound identification | Metabolite annotation, method validation [2] |

| PubChem | Chemical Database | Provides canonical SMILES and bioactivity data | Fingerprint calculation, model training [3] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Feature extraction, QSAR modeling [3] |

| PyFingerprint | Software Library | Generates molecular fingerprints from SMILES | Fingerprint calculation for ML [2] |

| OpenBabel | Chemical Toolbox | Handles chemical data format conversion | Structure manipulation, fingerprint generation [2] |

| XGBoost | ML Algorithm | Gradient boosting framework for structured data | High-performance fingerprint-based modeling [3] |

| COCONUT Database | Natural Product Database | Curated collection of unique natural products | Specialized chemical space exploration [1] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of molecular fingerprinting is undergoing rapid evolution, driven by advances in both experimental techniques and computational methods. Several key trends are shaping the future of spectral assignment:

Hybrid fingerprint representations that combine multiple data modalities represent a promising frontier. A 2025 study demonstrated a novel hybrid molecular fingerprint integrating chemical structure and mid-infrared (MIR) spectral data into a compact 101-bit binary descriptor [6]. Each bit reflects both the presence of a molecular substructure and a corresponding absorption band within defined MIR regions. While this approach showed modest predictive accuracy for logP prediction (RMSE 1.443) compared to traditional structure-based fingerprints (Morgan: RMSE 1.056, MACCS: RMSE 0.995), it offers unique interpretability by bridging experimental spectral evidence with cheminformatics modeling [6].

The integration of deep learning approaches for direct fingerprint prediction from spectral data continues to advance. Recent studies have demonstrated that deep learning models can effectively predict molecular fingerprints from MS/MS spectra, providing a powerful alternative to traditional spectral matching for metabolite identification [2]. These approaches are particularly valuable for identifying compounds not present in reference spectral libraries, addressing a significant bottleneck in metabolomics studies [2].

In spectroscopic instrumentation, recent developments include Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) based microscopy systems like the LUMOS II and Protein Mentor, which provide enhanced imaging capabilities for protein characterization in the biopharmaceutical industry [7]. Additionally, intelligent spectral enhancement techniques are achieving unprecedented detection sensitivity at sub-ppm levels while maintaining >99% classification accuracy, with transformative applications in pharmaceutical quality control, environmental monitoring, and remote sensing diagnostics [5].

As these technologies mature, we anticipate a shift toward more automated, accurate, and interpretable spectral assignment methods that will accelerate research across chemical, pharmaceutical, and materials science domains.

The discovery of the Raman Effect in 1928 by Sir C.V. Raman marked a pivotal moment in spectroscopic science, providing experimental validation for quantum theory and laying the groundwork for modern analytical techniques [8]. Raman and his student, K. S. Krishnan, observed that a small fraction of light scattered by a molecule undergoes a shift in wavelength, dependent on the molecule's specific chemical structure [8]. This "new kind of radiation" was exceptionally weak—only 1 part in 1 million to 1 part in 100 million of the source light intensity—requiring powerful illumination and long exposure times, sometimes up to 200 hours, to capture spectra on photographic plates [8]. Despite these challenges, Raman's clear demonstration and explanation of this scattering phenomenon earned him the sole recognition for the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics [8]. Today, Raman spectroscopy has evolved into a powerful, non-destructive technique that requires minimal sample preparation, delivers rich chemical and structural data, and operates effectively in aqueous environments and through transparent packaging [9]. Its applications span from carbon material analysis and pharmaceutical development to forensic science and art conservation [9].

Technological Evolution: From Early Challenges to Modern Instrumentation

The journey of Raman spectroscopy from a laboratory curiosity to a mainstream analytical tool is a story of technological innovation. Early instruments relied on sunlight or quartz mercury arc lamps filtered to specific wavelengths, primarily in the green region (435.6 nanometers), and used glass photographic plates for detection [8]. The advent of laser technology in the 1960s revolutionized the field, providing the intense, monochromatic light source that Raman spectroscopy desperately needed [10]. Modern Raman spectrometers utilize laser excitation, which provides a concentrated photon flux, combined with advanced filters, sensitive detectors, and quiet electronics, allowing for real-time spectral acquisition and imaging [8].

Table 1: Evolution of Key Raman Spectroscopy Components

| Era | Light Source | Detection System | Key Limitations | Major Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1928-1960s | Sunlight, Mercury Arc Lamps [8] | Glass Photographic Plates [8] | Extremely long exposure times (hours to days); very weak signal [8] | Discovery of the effect; compilation of first spectral libraries [8] |

| 1960s-1980s | Argon Ion, Nd:YAG, Ti:Sapphire Lasers [10] | Improved Electronic Detectors | Large, impractical laser systems; fluorescence interference [10] | Introduction of lasers; move to Near-IR (NIR) wavelengths to reduce fluorescence [10] |

| 1990s-Present | Diode Lasers, External Cavity Diode Lasers (ECDLs) [10] | Sensitive CCD Arrays, Portable Detectors | Portability and cost for clinical/field use [10] [11] | Miniaturization; robust, portable systems; fiber-optic probes; high-sensitivity detection [10] [11] |

A significant breakthrough was the shift to Near-Infrared (NIR) excitation (e.g., 785 nm). Since few biological fluorophores have peak emissions in the NIR, this move dramatically reduced the fluorescence background that often overwhelmed the modest Raman signals in biological samples [10]. The development of small, stable diode lasers and external cavity diode lasers (ECDLs) with linewidths of <0.001 nm lightened the footprint of Raman systems, making them suitable for clinical and portable applications [10]. Recent product introductions in 2024 highlight trends toward smaller, lighter, and more user-friendly instruments, including handheld devices for narcotics identification and purpose-built process analytical technology (PAT) instruments [11].

Comparative Analysis of Spectral Assignment Methods

Spectral assignment is the critical process of correlating spectral features, such as peak positions and intensities, with specific molecular vibrations and structures. Raman spectroscopy excels in providing sharp, chemically specific peaks that serve as molecular fingerprints, but it is one of several techniques used for this purpose.

Fundamental Principles of Raman Spectral Assignment

In Raman spectroscopy, the energy shift (Raman shift) in scattered light is measured relative to the excitation laser line and is directly related to the vibrational energy levels of the molecule [9]. Each band in a Raman spectrum can be correlated to specific stretching and bending modes of vibration. For example, in a phospholipid molecule like phosphatidyl-choline, distinct Raman bands can be assigned to its specific chemical bonds, providing a quantitative assessment of the sample's chemical composition [10]. The technique is particularly powerful for analyzing carbon materials, where it can identify bonding types, detect structural defects, and measure characteristics like graphene layers and nanotube diameters with unmatched precision [9].

Comparison with Alternative Spectral Assignment Techniques

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Spectral Assignment Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Spectral Information | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic light scattering [8] | Vibrational fingerprint; sharp, specific peaks [9] | Minimal sample prep; works through glass; ideal for aqueous solutions [9] | Very weak signal; susceptible to fluorescence [10] | In-situ analysis, biological samples, pharmaceuticals [9] |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Overtone/combination vibrations of X-H bonds [12] | Broad, overlapping bands requiring chemometrics [12] | Fast, intact to sample, high penetration depth [12] | Low structural specificity; complex data interpretation [12] | Quantitative analysis in agriculture, food, and process control [12] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Nuclear spins in a magnetic field [13] | Atomic environment, molecular structure & dynamics [13] | Rich structural and dynamic information; quantitative [13] | Low sensitivity; requires high-field instruments & expertise [13] | Protein structure determination, organic molecule elucidation [13] |

A systematic study of NIR spectral assignment revealed that the NIR absorption frequency of a skeleton structure with sp² hybridization (like benzene) is higher than one with sp³ hybridization (like cyclohexane) [12]. Furthermore, the absorption intensity of methyl-substituted benzene at 2330 nm was found to have a linear relationship with the number of substituted methyl C-H bonds, providing a theoretical basis for NIR quantification [12]. Such discoveries enhance the interpretability and robustness of spectral models.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for In Vivo Clinical Raman Spectroscopy

The application of Raman spectroscopy in clinical settings for real-time tissue diagnosis requires carefully controlled methodologies [10].

- Sample Illumination: A laser beam (typically a stable diode laser at 785 nm) is focused onto the tissue surface via a fiber-optic probe. Laser power at the sample is kept below the maximum permissible exposure (as per ANSI standards) to ensure patient safety and comfort, typically in the range of 100-300 mW for skin measurements [10].

- Signal Collection: The back-scattered light, containing both Raman signal and a strong Rayleigh component, is collected by the same probe. The probe incorporates specialized filters to reject the elastically scattered Rayleigh light while transmitting the weaker Raman signal [10].

- Spectral Dispersion and Detection: The filtered light is dispersed by a high-throughput spectrograph and detected by a sensitive charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, cooled to reduce thermal noise. Integration times for in vivo measurements are typically short (0.5–5 seconds) to enable real-time feedback [10].

- Data Pre-processing: The raw spectrum undergoes critical preprocessing steps to remove cosmic rays, correct for the instrument response function, subtract a fluorescent background, and normalize the data [10]. Advanced preprocessing methods, including context-aware adaptive processing and physics-constrained data fusion, are transforming the field by enabling unprecedented detection sensitivity [5].

Protocol for NIR Spectral Assignment of Hybridization Type

A described experiment to assign NIR spectra based on atomic hybridization proceeded as follows [12]:

- Sample Preparation: Pure samples of benzene (sp² hybridization) and cyclohexane (sp³ hybridization) were obtained. To ensure a fair comparison of absorption intensity, solutions with the same molar concentration were prepared in a suitable solvent like carbon tetrachloride [12].

- Data Acquisition: NIR spectra of both samples were collected using a standard NIR spectrometer, recording the raw absorbance across the spectrum [12].

- Data Processing: Second derivative (2nd) spectra were calculated from the raw spectra to enhance spectral resolution and eliminate baseline drift, making subtle peaks more discernible [12].

- Spectral Analysis and Assignment: The overtone and combination regions of the spectra for both compounds were compared. The study discovered that the C-H absorption frequencies for benzene were consistently higher than those for cyclohexane (e.g., the first overtone at 1660 nm vs. 1760 nm), conclusively demonstrating that the carbon atom with sp² hybridization has a larger absorption frequency [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent and Material Solutions

Successful experimentation in spectroscopic analysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectral Analysis

| Item | Function & Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Labels (e.g., D₂O) | Used to explore the effects of key chemical structural properties; deuterated bonds shift vibrational frequencies, aiding assignment [12]. | Probing hydrogen bonding and the influence of substituents on a core molecular structure [12]. |

| SERS Substrates (Gold/Silver Nanoparticles) | Enhance the intrinsically weak Raman signal by several orders of magnitude, enabling single-molecule detection [11]. | Detection of trace analytes in forensic science or environmental monitoring [9] [11]. |

| Fiber Optic Probes (e.g., FlexiSpec Raman Probe) | Enable remote, in-situ measurements; can be sterilized and are rugged for clinical or industrial process control [11]. | In vivo medical diagnostics inside the human body or monitoring chemical reactions in sealed vessels [9] [10]. |

| Spectral Libraries (e.g., 20,000-compound library) | Software databases used as reference for automated compound identification and quantification from spectral fingerprints [11]. | Rapid identification of unknown materials in pharmaceutical quality control or forensic evidence analysis [9] [11]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Well-characterized materials with known composition used for instrument calibration and validation of analytical methods. | Ensuring accuracy and regulatory compliance in quantitative pharmaceutical or clinical analyses [10]. |

The trajectory from C.V. Raman's seminal discovery to today's sophisticated spectroscopic tools underscores a century of remarkable innovation. The field is currently undergoing a transformative shift driven by several key trends. There is a strong movement towards miniaturization and portability, with handheld Raman devices becoming commonplace for on-site inspections and forensics [9] [11]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is revolutionizing data analysis. Intelligent preprocessing techniques are now achieving sub-ppm detection levels with over 99% classification accuracy, while AI-driven assignment algorithms are making spectral interpretation faster and more accessible [5]. Finally, the push for automation and user-friendliness is making these powerful techniques available to a broader range of users, though this also underscores the need for maintaining expertise to validate experimental data [11]. As these trends converge, Raman and other spectroscopic methods will continue to expand their impact, driving innovation in drug development, materials science, and clinical diagnostics.

The identification and quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the monitoring of critical quality attributes (CQAs) in bioprocessing, and the detection of counterfeit drugs represent significant challenges in pharmaceutical analysis. Vibrational spectroscopic techniques like Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, coupled with mass spectrometric methods like tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), provide complementary tools for addressing these challenges. This guide offers a comparative analysis of these fundamental technologies, focusing on their operational principles, applications, and performance metrics within the context of spectral assignment methods research.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Comparison

Raman spectroscopy measures the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser source. The resulting energy shifts provide a molecular fingerprint based on changes in polarizability during molecular vibrations [14]. Modern Raman instruments typically include a laser source, sample handling unit, monochromator, and a charge-coupled device (CCD) detector [15]. Its compatibility with aqueous solutions and minimal sample preparation make it particularly valuable for biological and pharmaceutical applications [14].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy operates on a different principle, measuring the absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds. Specific wavelengths are absorbed, causing characteristic vibrations that correspond to functional groups and molecular structures within the sample. FTIR is particularly valuable for identifying organic compounds, polymers, and pharmaceuticals [16].

Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) employs multiple stages of mass analysis separated by collision-activated dissociation. This technique provides structural information by fragmenting precursor ions and analyzing the resulting product ions, offering exceptional sensitivity and specificity for compound identification and quantification.

The following table summarizes the core principles and relative advantages of each technique:

Table 1: Fundamental Principles and Strengths of Analytical Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Primary Interaction | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic light scattering | Change in molecular polarizability | Excellent for aqueous samples; minimal sample preparation; suitable for in-situ analysis |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Infrared light absorption | Change in dipole moment | Excellent for organic and polar molecules; high sensitivity for polar bonds (O-H, C=O, N-H) |

| MS/MS | Mass-to-charge ratio separation | Ionization and fragmentation | Ultra-high sensitivity; structural elucidation; excellent specificity and quantitative capabilities |

Pharmaceutical Application Suitability

Each technique offers distinct advantages for specific pharmaceutical applications:

- API Identity Testing: Raman spectroscopy excels in identifying APIs, particularly using the "fingerprint in the fingerprint" region (1550–1900 cm⁻¹), where common excipients show no Raman signals, ensuring selective API detection [17].

- Process Monitoring: Raman serves as an ideal Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tool for real-time monitoring of biopharmaceutical downstream processes, such as Protein A chromatography [18].

- Counterfeit Detection: Both Raman and IR spectroscopy provide rapid, non-destructive analysis for detecting counterfeit drugs, with handheld models enabling field testing [19] [20].

- Structural Elucidation: MS/MS provides unparalleled capability for determining molecular structures and quantifying trace-level impurities and metabolites.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics in Pharmaceutical Applications

Recent studies provide quantitative performance data for these technologies in various pharmaceutical contexts:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Application | Technique | Experimental Results | Conditions/Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| CQA Prediction in Protein A Chromaturgy [18] | Raman Spectroscopy | Q² = 0.965 for fragments; Q² ≥ 0.922 for target protein concentration, aggregates, & charge variants | Butterworth high-pass filters & KNN regression; 28s resolution |

| API Identity Testing [17] | Raman Spectroscopy (1550-1900 cm⁻¹ region) | Unique Raman vibrations for all 15 APIs evaluated; no signals from 15 common excipients | FT-Raman spectrometer; 1064 nm laser; 4 cm⁻¹ resolution |

| Street Drug Characterization [20] | Handheld FT-Raman | Identification of TFMPP, cocaine, ketamine, MDMA in 254 products through packaging | 1064 nm laser; 490 mW power; 10 cm⁻¹ resolution; correlation with GC-MS |

| Counterfeit Syrup Detection [19] | Raman & UV-Vis with Multivariate Analysis | Detection limits as low as 0.02 mg/mL for acetaminophen, guaifenesin | Combined spectroscopy with multivariate analysis; minimal sample prep |

Side-by-Side Technique Comparison

Direct comparison of the techniques reveals complementary strengths and limitations:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Technique Characteristics

| Aspect | Raman Spectroscopy | FTIR Spectroscopy | MS/MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; non-destructive | Minimal for ATR; may require preparation for other modes | Extensive; often requires extraction and separation |

| Water Compatibility | Excellent (weak Raman scatterer) | Limited (strong IR absorber) | Compatible with aqueous solutions when coupled with LC |

| Detection Sensitivity | Lower for some samples but enhanced with SERS | Generally high for polar compounds | Extremely high (pg-ng levels) |

| Quantitative Capability | Good with multivariate calibration | Good with multivariate calibration | Excellent (wide linear dynamic range) |

| Portability | Handheld and portable systems available | Primarily lab-based with some portable systems | Laboratory-based |

| Key Limitations | Fluorescence interference; potential sample heating | Strong water absorption; limited container compatibility | High cost; complex operation; destructive |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodologies for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Raman Spectroscopy for CQA Monitoring in Bioprocessing

Objective: Implement Raman-based PAT for monitoring Critical Quality Attributes during Protein A chromatography [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Raman spectrometer system

- Tecan liquid handling station

- Protein A chromatography column

- Buffer solutions at appropriate pH and conductivity

- Monoclonal antibody sample

Procedure:

- System Setup: Connect Raman spectrometer to liquid handling station enabling high-throughput model calibration.

- Calibration: Collect Raman spectra of 183 samples with 8 CQAs within 25 hours.

- Spectral Processing: Apply Butterworth high-pass filters to remove background interference.

- Model Training: Utilize k-nearest neighbor (KNN) regression to build predictive models.

- Validation: Confirm model robustness using 19 external validation runs with varying elution pH, load density, and residence time.

- Implementation: Deploy model for real-time CQA prediction with 28-second temporal resolution.

Key Parameters: Laser wavelength: 785 nm or 1064 nm; Spectral range: 200-2000 cm⁻¹; Resolution: 4-10 cm⁻¹; Acquisition time: 28 seconds per spectrum [18].

API Identity Testing Using Raman Spectral Fingerprinting

Objective: Identify APIs in solid dosage forms using the specific Raman region of 1550-1900 cm⁻¹ [17].

Materials and Reagents:

- Thermo Nicolet NXR 6700 FT-Raman spectrometer or equivalent

- 180° reflectance attachment or microstage

- Solid dosage formulations (tablets, capsules)

- USP-compendium reference standards for APIs and excipients

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform spectral calibration using validation system (e.g., Thermo ValPro).

- Parameter Setting: Configure laser power (0.5-1.0 W for 1064 nm laser), spectral resolution (4 cm⁻¹), and range (150-3700 cm⁻¹).

- Spectral Collection: Acquire Raman spectra of reference excipients and APIs.

- Region Analysis: Focus spectral interpretation on 1550-1900 cm⁻¹ region.

- Pattern Recognition: Identify characteristic API vibrations (C=N, C=O, N=N functional groups).

- Validation: Compare unknown samples against reference spectral libraries.

Key Parameters: Laser wavelength: 1064 nm; Laser power: 0.5-1.0 W; Spectral resolution: 4 cm⁻¹; Number of scans: 64-128 [17].

Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the appropriate analytical technique based on pharmaceutical analysis requirements:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these analytical technologies requires specific reagents and materials:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | NIST-traceable calibration standards | Instrument calibration and validation | Ensure measurement accuracy and reproducibility [19] |

| SERS substrates (Au/Ag nanoparticles) | Signal enhancement for trace analysis | Provide 10⁶-10⁸ signal enhancement [21] | |

| USP-compendium reference standards | API and excipient identification | Certified identity and purity per pharmacopeial methods [17] | |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | ATR crystals (diamond, ZnSe) | Surface measurement without sample preparation | Enable direct analysis of solids and liquids [16] |

| Polarization accessories | Molecular orientation studies | Characterize polymer films and crystalline structures | |

| MS/MS Analysis | Stable isotope-labeled standards | Quantitative accuracy and recovery correction | Account for matrix effects and ionization variability |

| HPLC-grade solvents and mobile phases | Sample preparation and chromatographic separation | Minimize background interference and maintain system performance | |

| General Materials | Protein A chromatography resins | Bioprocess purification and CQA monitoring | Capture monoclonal antibodies for downstream analysis [18] |

| Buffer components (various pH) | Mobile phase preparation and sample reconstitution | Maintain biological activity and chemical stability |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of pharmaceutical analysis continues to evolve with several emerging trends:

- AI Integration: Machine learning libraries (PyTorch, Keras) are being integrated with Raman spectroscopy to handle complex datasets and minimize manual processing [22].

- Portable Systems: Growing adoption of handheld Raman spectrometers for on-site chemical analysis in pharmaceutical manufacturing and quality control [23] [20].

- CMOS-Based Sensors: Development of complementary metal-oxide semiconductor cameras and sensors for Raman spectroscopy, offering high quantum efficiency, lower noise, and reduced costs [22].

- Enhanced Techniques: Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS) are expanding application boundaries with enhanced sensitivity and subsurface analysis capabilities [15] [21].

The global Raman spectroscopy market, valued at $1.47 billion in 2025 and projected to reach $2.88 billion by 2034, reflects the growing adoption of these technologies in pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors [22].

Raman spectroscopy, MS/MS, and IR spectroscopy represent complementary fundamental technologies for comprehensive pharmaceutical analysis. Raman excels in PAT applications, API identity testing, and aqueous sample analysis; FTIR provides superior sensitivity for polar functional groups; while MS/MS offers unparalleled sensitivity and structural elucidation capabilities. The optimal technique selection depends on specific analytical requirements, sample characteristics, and operational constraints. As these technologies continue to evolve with AI integration, miniaturization, and enhancement approaches, their value in pharmaceutical development and quality control will further increase, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools for ensuring drug safety and efficacy.

Spectral libraries are indispensable tools in mass spectrometry (MS), serving as curated repositories of known fragmentation patterns that enable the identification of peptides and small molecules in complex samples. Their role is pivotal across diverse fields, from proteomics and drug development to food safety and clinical toxicology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of spectral library searching against alternative identification methods, detailing experimental protocols and presenting performance data to inform method selection in research and development.

The fundamental challenge in mass spectrometry is accurately matching an experimental MS/MS spectrum to the correct peptide or compound. Spectral library searching addresses this by comparing query spectra against a collection of reference spectra from previously identified analytes [24]. This method contrasts with database searching, which matches spectra against in-silico predicted fragment patterns generated from protein or compound sequences [25]. A third approach, emerging from advances in machine learning, uses deep learning models to learn complex matching patterns directly from spectral data, potentially bypassing the need for large physical libraries [25] [26].

The core value of a spectral library lies in its quality and comprehensiveness. As highlighted in the development of the WFSR Food Safety Mass Spectral Library, manually curated libraries acquired under standardized conditions provide a level of reliability and reproducibility that is crucial for confident identifications [27]. The utility of these libraries extends beyond simple searching; they are foundational for advanced techniques in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry, where complex spectra require high-quality reference libraries for deconvolution [24] [28].

Experimental Protocols for Library Construction and Searching

Spectral Library Generation Workflow

Creating a robust spectral library is a meticulous process that requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow, as implemented in platforms like PEAKS software and for the WFSR Food Safety Library, outlines the key steps [24] [27]:

- Sample Preparation: Proteins are digested into peptides using specific enzymes (e.g., trypsin), or compound standards are prepared in pure solutions. For comprehensive coverage, fractionation is often recommended.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis with DDA: Samples are analyzed using Liquid Chromatography (LC) coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer operating in Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) mode. In DDA, the top N most intense precursors eluting at a given time are selected for fragmentation.

- Database Search & Curated Identification: The resulting DDA spectra are searched against a sequence database using search engines (e.g., PEAKS DB, Comet, MS-GF+) to identify peptides with confidence, typically controlled by a False Discovery Rate (FDR) threshold [24].

- Library Assembly & Curation: Confidently identified spectra, along with metadata like precursor charge, retention time (often converted to an indexed Retention Time (iRT)), and fragment ion intensities, are compiled into a spectral library. Manual curation ensures quality [27].

The diagram below illustrates this multi-stage process for building a spectral library.

Spectral Library Searching Protocol

Once a library is established, it can be used to identify compounds in new experimental data. A typical spectral library search, as implemented in software like MZmine and PEAKS, involves the following parameters and steps [24] [29]:

- Data Input: Query spectra are obtained from DDA or converted from DIA data via deconvolution.

- Spectral Matching: The similarity between a query spectrum and every library spectrum is calculated using algorithms like weighted cosine similarity (for MS2 data) or composite cosine identity (for GC-EI-MS data) [29].

- Result Filtering: Matches are filtered based on a similarity score threshold and often an FDR estimated using a decoy library approach, where shuffled versions of library spectra are searched simultaneously [24].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Library Searching vs. Database Searching and Novel Deep Learning Methods

The choice of identification method significantly impacts the number and confidence of identifications. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison based on benchmarking studies of peptides and small molecules [25] [26] [30].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Spectral Assignment Methods

| Method Category | Specific Tool | Key Principle | Reported Performance | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Library Search | SpectraST | Matches experimental spectra to a library of reference spectra. | 45% more cross-linked peptide IDs vs. sequence database search (ReACT) [30]. | Fast, leverages empirical data for high accuracy. | Limited to compounds already in the library. |

| Sequence Database Search | MS-GF+ | Compares spectra to in-silico predicted spectra from a sequence database. | Baseline identification rate [25]. | Can identify novel peptides not in any library. | Lower specificity and sensitivity vs. library search [30]. |

| Machine Learning Rescoring | Percolator | Uses semi-supervised ML to re-score and filter database search results. | Improved IDs over raw search engine scores [25]. | Boosts performance of any database search. | Does not directly use spectral peak information. |

| Deep Learning Filter | WinnowNet | Uses CNN/Transformers to learn patterns from PSM data via curriculum learning. | Achieved more true IDs at 1% FDR than Percolator, MS2Rescore, and DeepFilter [25]. | State-of-the-art performance; can generalize across samples. | Requires significant computational resources for training. |

| LLM-Based Embedding | LLM4MS | Leverages Large Language Models to create spectral embeddings for matching. | Recall@1 of 66.3%, a 13.7% improvement over Spec2Vec [26]. | Incorporates chemical knowledge for better matching. | Complex model; requires fine-tuning on spectral data. |

Quantitative Benchmarking in Metaproteomics and Metabolomics

Independent evaluations across different application domains demonstrate the performance gains of advanced methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking Results Across Applications

| Application Domain | Benchmark Dataset | WinnowNet (PSMs) | Percolator (PSMs) | DeepFilter (PSMs) | Library Search (Relationships) | ReACT (Relationships) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metaproteomics [25] | Marine Community | 12,500 | 9,200 | 10,800 | - | - |

| Metaproteomics [25] | Human Gut | 9,800 | 7,100 | 8,500 | - | - |

| XL-MS (Cross-linking) [30] | A. baumannii (Library-Query) | - | - | - | 419 | 290 |

In metaproteomics, WinnowNet consistently identified more peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) at a controlled 1% FDR compared to other state-of-the-art filters like Percolator and DeepFilter across various sample types, from marine microbial communities to human gut microbiomes [25]. In the specialized field of cross-linking MS (XL-MS), a spectral library search with SpectraST identified 419 cross-linked peptide pairs from a sample, a 45% increase compared to the 290 pairs identified by the conventional ReACT database search method [30].

For small molecule identification, the novel LLM4MS method was evaluated on a set of 9,921 query spectra from the NIST23 library. It achieved a Recall@1 (the correct compound ranked first) of 66.3%, significantly outperforming Spec2Vec (52.6%) and traditional weighted cosine similarity (58.7%) [26]. This demonstrates how leveraging deep learning can push the boundaries of identification accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of spectral library methods requires a combination of standardized materials, specialized software, and curated data repositories.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Spectral Library Research

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Pure Compound Standards | Essential for generating high-quality, curated spectral libraries of target compounds. | WFSR Food Safety Library (1001 compounds) [27]. |

| Software & Algorithms | Spectral Search Software | Performs the core matching between query and library spectra. | PEAKS (Library Search), SpectraST, MZmine [24] [29] [30]. |

| Database Search Engines | Identifies spectra for initial library building and provides a comparison method. | Comet, MS-GF+, Myrimatch [25]. | |

| Advanced Rescoring Tools | Employs ML/DL to improve identification rates from database searches. | WinnowNet, Percolator, MS2Rescore [25]. | |

| Data Resources | Public Spectral Libraries | Provide extensive reference data for compound annotation, especially for small molecules. | MassBank of North America (MoNA), GNPS, NIST, HMDB [29] [27]. |

| Instrumentation | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Generates high-quality MS/MS spectra with high mass accuracy and resolution. | Thermo Scientific Orbitrap IQ-X Tribrid [27]. |

Spectral libraries provide a powerful and efficient pathway for compound identification by leveraging empirical data, often outperforming traditional database searches in sensitivity. The emergence of deep learning methods like WinnowNet and LLM4MS represents a significant leap forward, offering even greater identification accuracy by learning complex patterns directly from spectral data. The optimal choice of method depends on the research goal: spectral library searching is ideal for high-throughput identification of known compounds, database searching is essential for discovering novel entities, and deep learning rescoring can maximize information extraction from complex datasets. As these technologies mature and integrate, they will continue to drive advances in proteomics, metabolomics, and drug development by making compound identification faster, more accurate, and more comprehensive.

The field of spectral analysis has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from manual interpretation by highly trained specialists to sophisticated, computationally driven workflows. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in spectral assignment methods research, where the comparative analysis of different techniques reveals a clear trajectory toward automation, intelligence, and integration. The drivers for this shift are multifaceted, stemming from the increasing complexity of analytical challenges in fields like biopharmaceuticals and the simultaneous advancement of computational power and algorithmic innovation [31]. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern computational spectral analysis tools and methods against traditional approaches, framing them within the broader thesis of a comparative analysis of spectral assignment methods research. The evaluation is grounded in experimental data and current market offerings, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear-eyed view of the evolving technological landscape.

Drivers of the Computational Shift

The transition to computational analysis is not arbitrary; it is a necessary response to specific pressures and opportunities within modern scientific research.

- Data Complexity and Volume: Modern spectroscopic techniques, such as those used for assessing the higher-order structure (HOS) of biopharmaceuticals, generate complex, high-dimensional data. Manual, subjective comparison of these spectra is no longer sufficient to meet rigorous regulatory guidelines like ICH-Q5E and ICH-Q6B, which demand objective, quantitative evaluation of spectral similarity for assessing structural comparability [32].

- The Demand for Speed and Reproducibility: In drug discovery, the pressure to reduce attrition and compress timelines is immense [31]. Manual analysis is a bottleneck, susceptible to human error and inconsistency. Computational methods enable rapid, reproducible analysis, accelerating critical phases like hit-to-lead optimization and supporting the high-throughput screening strategies that are becoming standard [33].

- Algorithmic and Hardware Advancement: The maturation of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning, has provided the tools to extract deeper insights from spectral data. Furthermore, innovations in instrumentation itself, such as quantum cascade laser (QCL) based microscopes that can image at a rate of 4.5 mm² per second, create data streams that can only be handled with computational assistance [7].

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between these primary drivers and their collective impact on research practices.

Milestones in Instrumentation and Software

The market introduction of new spectroscopic instruments and software platforms in 2024-2025 provides concrete evidence of the computational shift. These products are increasingly defined by their integration of automation, specialized data processing, and targeted application workflows.

Table 1: Comparison of Recently Introduced Spectral Analysis Instruments (2024-2025)

| Instrument | Vendor | Technology | Key Computational Feature | Targeted Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertex NEO Platform [7] | Bruker | FT-IR Spectrometer | Vacuum ATR accessory removing atmospheric interferences; multiple detector positions. | Protein studies, far-IR analysis. |

| FS5 v2 [7] | Edinburgh Instruments | Spectrofluorometer | Increased performance and capabilities for data acquisition. | Photochemistry, photophysics. |

| Veloci A-TEEM Biopharma Analyzer [7] | HORIBA Instruments | A-TEEM (Absorbance, Transmittance, EEM) | Simultaneous data collection providing an alternative to traditional separation methods. | Biopharmaceuticals (monoclonal antibodies, vaccines). |

| LUMOS II ILIM [7] | Bruker | QCL-based IR Microscope | Patented spatial coherence reduction to reduce speckle; fast imaging. | General-purpose microspectroscopy. |

| ProteinMentor [7] | Protein Dynamic Solutions | QCL-based Microscopy | Designed from the ground up for protein samples in biopharma. | Protein impurity ID, stability, deamidation. |

| SignatureSPM [7] | HORIBA Instruments | Raman/Photoluminescence with SPM | Integration of scanning probe microscopy with Raman spectroscopy. | Materials science, semiconductors. |

Concurrently, the software landscape for drug discovery has evolved to prioritize AI and automation. Platforms are now evaluated on their AI capabilities, specialized modeling techniques, and user accessibility [34]. For instance, Schrödinger's platform uses quantum mechanics and machine learning for molecular modeling, while deepmirror's generative AI engine is designed to accelerate hit-to-lead optimization [34].

Comparative Analysis of Spectral Distance Methods

A critical area of computational spectral analysis is the objective comparison of spectral similarity, crucial for applications like confirming the structural integrity of biologic drugs. Research has systematically evaluated various spectral distance calculation methods to move beyond subjective, visual assessment.

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A robust methodology for comparing spectral distance methods involves creating controlled sample sets and testing algorithms under realistic noise conditions [32].

- Sample Preparation: Use well-characterized proteins, such as the antibody drug Herceptin and human IgG, dissolved at specific concentrations (e.g., 0.80 mg/mL for far-UV Circular Dichroism (CD) measurements) [32].

- Data Acquisition: Measure CD spectra using a high-performance spectrometer (e.g., JASCO J-1500) under controlled parameters for near- and far-UV regions [32].

- Dataset Construction: Create comparison sets by combining actual spectra with simulated noise and fluctuations to mimic real-world pipetting errors. This tests algorithm robustness [32].

- Algorithm Testing: Calculate spectral distances using multiple methods on the same dataset. Key methods include:

- Euclidean Distance (ED) & Manhattan Distance (MD)

- Normalized Euclidean Distance (NED) & Normalized Manhattan Distance (NMD)

- Correlation Coefficient (R)

- Derivative Correlation Algorithm (DCA) & Area of Overlap (AOO) [32]

- Weighting Functions: Test the performance of these algorithms when combined with weighting functions, such as:

- Spectral Intensity Weighting (

ω_spec): Emphasizes regions with strong signal. - Noise Weighting (

ω_noise): Down-weights noisy spectral regions. - External Stimulus Weighting (

ω_ext): Focuses on regions known to change under specific conditions (e.g., temperature, impurities) [32].

- Spectral Intensity Weighting (

- Performance Evaluation: Assess the sensitivity and robustness of each method/weighting combination in detecting known, subtle spectral changes while ignoring irrelevant noise.

The following workflow diagram visualizes this experimental protocol.

Performance Data and Comparison

Experimental results provide a quantitative basis for selecting the optimal spectral comparison method. The data below summarizes findings from a comprehensive evaluation of distance methods and preprocessing techniques for CD spectroscopy [32].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Spectral Distance Calculation Methods for CD Spectra

| Method Category | Specific Method | Key Finding / Performance | Recommended Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Distance Metrics | Euclidean Distance (ED) | Effective for spectral distance assessment. | Savitzky-Golay noise reduction [32]. |

| Manhattan Distance (MD) | Effective for spectral distance assessment. | Savitzky-Golay noise reduction [32]. | |

| Normalized Metrics | Normalized Euclidean Distance | Cancels out whole-spectrum intensity changes. | L2 norm during normalization [32]. |

| Normalized Manhattan Distance | Cancels out whole-spectrum intensity changes. | L1 norm during normalization [32]. | |

| Correlation-Based Methods | Correlation Coefficient (R) | Does not consider whole-spectrum intensity changes. | N/A |

| Derivative Correlation Algorithm (DCA) | Uses first derivative spectra for comparison. | N/A | |

| Weighting Functions | Spectral Intensity (ω_spec) |

Preferable to combine with noise weighting [32]. | Normalize absolute reference spectrum by mean value [32]. |

Noise (ω_noise) |

Improves robustness by down-weighting noisy regions [32]. | Derived from standard deviation of HT noise spectrum [32]. | |

External Stimulus (ω_ext) |

Should be considered to improve sensitivity to known changes [32]. | Based on difference spectrum from external stimulus [32]. |

The overarching conclusion from this research is that using Euclidean distance or Manhattan distance with Savitzky-Golay noise reduction is highly effective. Furthermore, the combination of spectral intensity and noise weighting functions is generally preferable, with the optional addition of an external stimulus weighting function to heighten sensitivity to specific, known changes [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The execution of robust spectral analysis, whether for method comparison or routine characterization, relies on a foundation of high-quality materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectral Analysis

| Item | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibody (e.g., Herceptin) [32] | A well-characterized biologic standard used as a model system for developing and validating spectral comparison methods, especially for biosimilarity studies. |

| Human IgG [32] | Serves as a reference or, in mixture experiments, as a simulated "impurity" to test the sensitivity of spectral distance algorithms. |

| Variable Domain of Heavy Chain Antibody (VHH) [32] | A next-generation antibody format used as a novel model protein for evaluating analytical methods. |

| Milli-Q Water Purification System [7] | Provides ultrapure water essential for sample preparation, buffer formulation, and mobile phases to avoid spectral interference from contaminants. |

| PBS Solution (20 mM) [32] | A standard physiological buffer for dissolving and stabilizing protein samples during spectral analysis like Circular Dichroism (CD). |

The evidence from recent product releases and rigorous methodological research confirms that the shift from manual to computational analysis is both entrenched and accelerating. The drivers—data complexity, the need for speed, and algorithmic advancement—continue to gain force. The milestones in instrumentation show a clear trend toward automation, targeted application, and integrated data processing, while software evolution is dominated by AI and cloud-based platforms. The comparative analysis of spectral distance methods provides a definitive example of this shift: objective, computationally-driven algorithms like weighted Euclidean distance have been empirically shown to outperform subjective visual assessment, delivering the robustness, sensitivity, and quantitative output required by modern regulatory science and high-throughput drug discovery. For researchers, the imperative is clear: adopting and mastering these computational tools is no longer optional but fundamental to success in spectral assignment and characterization.

Methodological Approaches and Transformative Applications in Drug Discovery and Diagnostics

In shotgun proteomics, the identification of peptides from tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data is a critical step. This process primarily relies on two computational paradigms: sequence database searching (exemplified by SEQUEST) and spectral library searching (exemplified by SpectraST). Both methods aim to match experimental MS/MS spectra to peptide sequences, but they differ fundamentally in their approach and underlying philosophy. SEQUEST, one of the earliest database search engines, compares experimental spectra against theoretical spectra generated in silico from protein sequence databases [35]. In contrast, SpectraST utilizes carefully curated libraries of previously observed and identified experimental spectra as references [36] [37]. This comparative analysis examines the performance, experimental applications, and complementary strengths of these two approaches within the framework of modern proteomics workflows.

SEQUEST: Database Search Engine

SEQUEST operates by comparing an experimental MS/MS spectrum against a vast number of theoretical spectra derived from a protein sequence database. Its workflow involves:

- Theoretical Spectrum Generation: For each putative peptide sequence in the database (considering factors like enzymatic digestion and potential modifications), SEQUEST predicts a theoretical fragmentation pattern, typically including primarily b- and y-type ions at fixed intensities [36].

- Preliminary Scoring (Sp): The algorithm first computes a preliminary score (Sp) based on the number of peaks common to the experimental and theoretical spectra [38].

- Cross-Correlation Analysis (XCorr): The top candidate peptides (e.g., 500 by default) ranked by Sp undergo a more computationally intensive cross-correlation analysis. This calculates the correlation between the experimental spectrum and the theoretical spectrum for each candidate, resulting in the XCorr score [35] [38].

- Normalized Score (ΔCn): The ΔCn score represents the difference between the XCorr of the top-ranked peptide and the next best candidate, normalized by the top XCorr. This helps assess the uniqueness of the match [38].

A key challenge in SEQUEST analysis is optimizing filtering criteria (Xcorr, ΔCn) to maximize true identifications while controlling the false discovery rate (FDR), often assessed using decoy database searches [38].

SpectraST: Spectral Library Search Engine

SpectraST leverages a "library building" paradigm, creating searchable spectral libraries from high-confidence identifications derived from previous experiments [36] [37]. Its mechanism involves:

- Library Creation: A spectral library is meticulously compiled from a large collection of previously observed and confidently identified peptide MS/MS spectra. SpectraST can build libraries from various inputs, including search results from SEQUEST, Mascot, and other engines in pepXML format [36] [37]. A key feature is its consensus creation algorithm, which coalesces multiple replicate spectra identified as the same peptide ion into a single, high-quality representative consensus spectrum [37].

- Spectral Searching: The unknown query spectrum is compared directly to all library entry spectra. The similarity scoring is based on the direct comparison of experimental spectra, leveraging actual peak intensities and the presence of uncommon or unknown fragment ions that are often absent from theoretical models [36] [39].

- Quality Filtering: During library building, various quality filters are implemented to remove questionable and low-quality spectra, which is crucial for the library's search performance [37].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for both SEQUEST and SpectraST.

Performance Comparison: Speed, Accuracy, and Coverage

Direct comparisons between SpectraST and SEQUEST reveal distinct performance characteristics, driven by their fundamental differences in searching a limited library of observed peptides versus a vast database of theoretical sequences.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of SpectraST and SEQUEST

| Performance Metric | SpectraST | SEQUEST | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Speed | ~0.001–0.01 seconds/spectrum [36] | ~5–20 seconds/spectrum [36] | Search against a library of ~50,000 entries vs. human IPI database on a modern PC. |

| Discrimination Power | Superior discrimination between good and bad matches [36] [39] | Lower discrimination power compared to SpectraST [39] | Leads to improved sensitivity and false discovery rates for spectral searching. |

| Proteome Coverage | Limited to peptides in the library; can miss novel peptides. | Can identify any peptide theoretically present in the database. | In one study, SpectraST identified 3,295 peptides vs. SEQUEST's 1,326 from the same data [40]. |

| Basis of Comparison | Compares experimental spectra to experimental spectra [36] | Compares experimental spectra to theoretical spectra [36] | Theoretical spectra are often simplistic, lacking real-world peak intensities and fragments. |

Analysis of Performance Differences

The performance disparities stem from core methodological differences. SpectraST's speed advantage arises from a drastically reduced search space, as it only considers peptide ions previously observed in experiments, unlike SEQUEST, which must consider all putative peptide sequences from a protein database, most of which are never observed [36]. Furthermore, SpectraST's precision is enhanced because it uses actual experimental spectra as references. This allows it to utilize all spectral features, including precise peak intensities, neutral losses, and uncommon fragments, leading to better scoring discrimination [36] [37]. SEQUEST's theoretical spectra are simpler models, typically including only major ion types (e.g., b- and y-ions) at fixed intensities, which do not fully capture the complexity of real experimental data [36].

However, SEQUEST maintains a critical advantage in its potential for novel discovery, as it can identify any peptide whose sequence exists in the provided database. SpectraST is inherently limited to peptides that have been previously identified and incorporated into its library, making it less suited for discovery-based applications where new peptides or unexpected modifications are sought [40].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Building a Consensus Spectral Library with SpectraST

A typical protocol for constructing a high-quality spectral library with SpectraST, as validated using datasets from the Human Plasma PeptideAtlas, involves the following steps [37]:

- Input Data Preparation: Collect MS/MS data files (e.g., in .mzXML format) and their corresponding peptide identification results from sequence search engines (SEQUEST, Mascot, X!Tandem, etc.) converted to the open pepXML format via the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (TPP) [37].

- Library Creation Command: Use SpectraST in create mode (

-c). The basic command structure isspectrast -cF<parameter_file> <list_of_pepXML_files>. - Consensus Spectrum Generation: The software groups all replicate spectra identified as the same peptide ion and applies a consensus algorithm to coalesce them into a single, high-quality representative spectrum for the library [37].

- Application of Quality Filters: Implement various quality filters during the build process to remove questionable and low-quality spectra. This is a crucial step to ensure the resulting library's reliability [37].

- Library Validation: The quality of the built library can be validated by using it to re-search the original datasets and assessing the identification performance (sensitivity, FDR) as a benchmark [37].

Optimizing SEQUEST Database Searching

To improve the performance and confidence of SEQUEST identifications, an optimized filtering protocol using a decoy database and machine learning has been developed [38]:

- Composite Database Search: Search all MS/MS spectra against a composite database containing the original protein sequences (forward) and their reversed sequences (decoy) [38].

- FDR Calculation: For a given set of filtering criteria (e.g., Xcorr and ΔCn cutoffs), calculate the False Discovery Rate (FDR) using the formula: FDR = 2 × n(rev) / (n(rev) + n(forw)), where n(rev) and n(forw) are the numbers of peptides identified from the reversed and forward databases, respectively [38].

- Filter Optimization with Genetic Algorithm (GA): Use a GA-based approach (e.g., SFOER software) to optimize the multiple SEQUEST score filtering criteria (Xcorr, ΔCn, etc.) simultaneously. The fitness function is designed to maximize the number of peptide identifications (n(forw)) while constraining the FDR to a user-defined level (e.g., <1%) [38].

- Application of Optimized Criteria: Apply the GA-optimized, sample-tailored filtering criteria to isolate confident peptide identifications. This approach has been shown to increase peptide identifications by approximately 20% compared to conventional fixed criteria at the same FDR [38].

Table 2: Key Resources for Spectral Assignment Experiments

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (TPP) | A suite of open-source software for MS/MS data analysis; integrates SpectraST and tools for converting search results to pepXML. | Workflow support from raw data conversion to validation, quantification, and visualization [36] [37]. |

| Spectral Library (e.g., from NIST) | A curated collection of reference MS/MS spectra from previously identified peptides. | Used as a direct reference for SpectraST searches; available for common model organisms [37]. |

| Decoy Database | A sequence database where all protein sequences are reversed (or randomized). | Essential for empirical FDR estimation for both SEQUEST and SpectraST results [38]. |

| PepXML Format | An open, standardized XML format for storing peptide identification results. | Serves as a key input format for SpectraST when building libraries from search engine results [37]. |

| Genetic Algorithm Optimizer (SFOER) | Software for optimizing SEQUEST filtering criteria to maximize identifications at a fixed FDR. | Tailoring search criteria for specific sample types to improve proteome coverage [38]. |

SpectraST and SEQUEST represent two powerful but philosophically distinct approaches to peptide identification. SpectraST excels in speed and discrimination for targeted analyses where high-quality spectral libraries exist, making it ideal for validating and quantifying known peptides efficiently [36] [39]. SEQUEST remains indispensable for discovery-oriented projects aimed at identifying novel peptides, sequence variants, or unexpected modifications, thanks to its comprehensive search of theoretical sequence space [35] [40].

The choice between them is not mutually exclusive. In practice, they can be powerfully combined. A robust strategy involves using SEQUEST for initial discovery and broad identification, followed by the construction of project-specific spectral libraries from these high-confidence results. Subsequent analyses, especially repetitive quality control or targeted quantification experiments on similar samples, can then leverage SpectraST for its superior speed and accuracy. Furthermore, optimization techniques, such as GA-based filtering for SEQUEST and rigorous quality control during SpectraST library building, are critical for maximizing the performance of either tool [37] [38]. Understanding their complementary strengths allows proteomics researchers to design more efficient, accurate, and comprehensive data analysis workflows.

The field of spectral analysis has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of sophisticated deep learning architectures. Traditional methods for processing spectral data often struggled with limitations in resolution, noise sensitivity, and the ability to capture complex, non-linear patterns in high-dimensional data. The emergence of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and Transformer models has fundamentally reshaped this landscape, enabling unprecedented capabilities in spectral enhancement tasks across diverse scientific domains. This comparative analysis examines the performance, methodological approaches, and practical implementations of these architectures within the broader context of spectral assignment methods research, providing critical insights for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on precise spectral data interpretation.

The significance of spectral enhancement extends across multiple disciplines, from pharmaceutical development where Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy assesses higher-order protein structures for antibody drug characterization [32], to environmental monitoring where hyperspectral imagery enables precise land cover classification [41], and water color remote sensing where spectral reconstruction techniques enhance monitoring capabilities [42]. In each domain, the core challenge remains consistent: extracting meaningful, high-fidelity information from often noisy, incomplete, or resolution-limited spectral data. Deep learning models have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in addressing these challenges through their capacity to learn complex hierarchical representations and capture both local and global dependencies within spectral datasets.

Architectural Comparison: Capabilities and Mechanisms

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Local Feature Extraction

CNNs excel at capturing local spatial-spectral patterns through their hierarchical structure of convolutional layers. In spectral enhancement tasks, CNNs leverage their inductive bias for processing structured grid data, making them particularly effective for extracting fine-grained details from spectral signatures. The architectural strength of CNNs lies in their localized receptive fields, which systematically scan spectral inputs to detect salient features regardless of their positional location within the data. However, traditional CNN architectures face inherent limitations in modeling long-range dependencies due to their localized operations, which can restrict their ability to capture global contextual information in complex spectral datasets [41].

Recent advancements have addressed these limitations through innovative architectural modifications. The DSR-Net framework employs a residual neural network architecture specifically designed for spectral reconstruction in water color remote sensing, demonstrating that deep CNN-based models can achieve significant error reduction when properly configured [42]. Similarly, multiscale large kernel asymmetric convolutional networks have been developed to efficiently capture both local and global spatial-spectral features in hyperspectral imaging applications [41]. These enhancements substantially improve the modeling capacity of CNNs for spectral enhancement while maintaining their computational efficiency advantages for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Transformer Architectures for Global Context Modeling

Transformers have revolutionized spectral processing through their self-attention mechanisms, which enable direct modeling of relationships between all elements in a spectral sequence regardless of their positional distance. This global receptive field provides Transformers with a distinctive advantage for capturing long-range dependencies in spectral data, allowing them to model complex interactions across different spectral regions simultaneously. The attention mechanism dynamically weights the importance of different spectral components, enabling the model to focus on the most informative features for a given enhancement task [41].

The PGTSEFormer (Prompt-Gated Transformer with Spatial-Spectral Enhancement) exemplifies architectural innovations in this space, incorporating a Channel Hybrid Positional Attention Module (CHPA) that adopts a dual-branch architecture to concurrently capture spectral and spatial positional attention [41]. This approach enhances the model's discriminative capacity for complex feature categories through adaptive weight fusion. Furthermore, the integration of a Prompt-Gated mechanism enables more effective modeling of cross-regional contextual information while maintaining local consistency, significantly enhancing the ability for long-distance dependent modeling in hyperspectral image classification tasks [41]. These architectural advances have demonstrated considerable success, with reported overall accuracies exceeding 97% across multiple HSI datasets [41].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Structured Data Representation