Chemical Probes for Target Identification: Strategies, Applications, and Best Practices in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical probes as indispensable tools for identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds in biological systems.

Chemical Probes for Target Identification: Strategies, Applications, and Best Practices in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chemical probes as indispensable tools for identifying the molecular targets of bioactive compounds in biological systems. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, core methodologies like Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) and Compound-Centered Chemical Proteomics (CCCP), and practical guidance for probe design, troubleshooting, and validation. The scope extends from basic concepts to advanced applications in drug discovery, phenotypic screening, and personalized medicine, synthesizing the latest trends to serve as a strategic guide for employing these powerful tools in biomedical research.

What Are Chemical Probes? Defining the Precision Tools of Modern Biology

Chemical probes are highly selective, cell-permeable small molecules designed to modulate the function of specific proteins or protein families in biological systems. They serve as indispensable tools for interrogating complex biological processes, validating therapeutic targets, and elucidating the mechanistic basis of human diseases [1]. Unlike small-molecule drugs, which may exert therapeutic effects through polypharmacology, chemical probes are engineered for precision and selectivity, enabling researchers to dissect the specific contributions of individual proteins to cellular phenotypes [1]. The availability of high-quality chemical probes has transformed biomedical research, providing insights that would be difficult or impossible to obtain using genetic approaches alone [1].

The fundamental value of chemical probes lies in their ability to rapidly and reversibly inhibit protein function in virtually any cell type or animal model, revealing temporal features of target inhibition that complement static genetic approaches [1]. When coupled with techniques like RNA interference, they can distinguish between effects due to protein scaffolding and catalytic activity, providing unprecedented mechanistic resolution [1]. Furthermore, results obtained with chemical probes have direct translational relevance as they mimic the pharmacology realized when therapeutic small molecules are used [1].

Defining High-Quality Chemical Probes

Essential Quality Criteria

The scientific community has established rigorous criteria for high-quality chemical probes to ensure biological data generated with these tools is meaningful and reproducible. According to expert consensus, a high-quality chemical probe should demonstrate potent in vitro activity (typically <100 nM IC₅₀ or Kᵢ), substantial selectivity (>30-fold relative to related proteins within the same family), and confirmed cellular activity (EC₅₀ < 1 μM in a relevant cellular assay) [1] [2]. These parameters ensure the probe engages its intended target under physiological conditions without significant off-target effects that could confound experimental interpretation.

The Structural Genomics Consortium, a leading collaboration of academic and industry scientists, has established additional standards requiring probes to be profiled against industry-standard panels of pharmacologically relevant off-targets and to have demonstrated on-target effects in cells [1]. Perhaps most importantly, high-quality probes should be accompanied by structurally similar but inactive control compounds that enable researchers to distinguish specific target-mediated effects from non-specific consequences of chemical treatment [1].

Table 1: Quality Criteria for Chemical Probes

| Parameter | Minimum Standard | Ideal Profile | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Potency | <100 nM IC₅₀/Kᵢ | <10 nM IC₅₀/Kᵢ | Biochemical assays, SPR, ITC |

| Selectivity | >30-fold within protein family | >100-fold with minimal off-targets | Selectivity panels, chemoproteomics |

| Cellular Activity | <1 μM EC₅₀ | <100 nM EC₅₀ | Cellular target engagement assays |

| Selectivity Verification | Profiled against relevant off-targets | Comprehensive profiling across diverse target classes | Broad screening panels, functional assays |

| Control Compounds | Available for major probe classes | Matched inactive analog for every probe | Synthetic chemistry, analytical characterization |

Chemical Probes vs. Small-Molecule Drugs

It is crucial to distinguish chemical probes from small-molecule drugs, as they serve different purposes and have distinct optimization parameters. While drugs must demonstrate favorable pharmacokinetic properties, safety profiles, and often benefit from polypharmacology, chemical probes prioritize maximal selectivity and mechanistic clarity above all other characteristics [1]. A drug may successfully treat a condition through simultaneous modulation of multiple targets, whereas a chemical probe must isolate the function of a single target with precision to enable definitive biological inference [1].

Chemical probes also differ from simple screening hits or tool compounds in their comprehensive characterization and validation. Many commercially available compounds are marketed as "probes" despite insufficient characterization, leading to problematic research conclusions. The continued use of poorly characterized probes has been identified as a significant issue, generating research of questionable validity at great cost to funding organizations and scientific careers [1].

Design Strategies and Mechanisms of Action

Architectural Principles

Chemical probes typically comprise several key structural elements: a targeting moiety that confers specificity for the protein of interest, a linker region that provides spatial orientation, and often a reporter group that enables detection or capture [3] [2]. The targeting moiety may be derived from known substrates, inhibitors, or natural products that interact with the target protein, optimized through medicinal chemistry to enhance potency and selectivity [3].

For enzyme-targeted probes, three primary design strategies predominate: (1) Substrate-based probes that incorporate recognition sequences undergoing enzymatic transformation; (2) Inhibitor-based probes containing reactive groups that covalently and irreversibly bind the active site; and (3) Affinity-based probes that bind non-covalently or via photo-crosslinking, often derived from known inhibitors [3]. Each approach offers distinct advantages depending on the experimental context, with substrate-based probes often providing signal amplification through catalytic turnover, while inhibitor-based probes yield direct stoichiometric readouts of catalytic function [3].

Covalent vs. Non-Covalent Mechanisms

Covalent chemical probes represent a particularly powerful class of reagents that form irreversible bonds with their target proteins [4]. These probes typically incorporate electrophilic warheads that react with nucleophilic amino acid residues (e.g., cysteine, lysine) in the target protein's active site [4]. Historically, covalent targeting was avoided due to selectivity concerns, but modern approaches rationally design covalent probes with optimized reactivity to achieve exceptional selectivity [4]. Covalent probes offer unique advantages, including prolonged target engagement, simplified confirmation of engagement through mass shift detection, and compatibility with activity-based protein profiling applications [4].

Non-covalent probes operate through traditional reversible binding interactions and remain the most common probe modality. These probes must overcome the significant challenge of achieving sufficient selectivity through structural complementarity alone, without the reinforcing mechanism of covalent bond formation [3]. Recent advances in structural biology and computational chemistry have dramatically improved the design of non-covalent probes, enabling researchers to exploit subtle differences in binding sites to achieve remarkable selectivity, even within large protein families with conserved active sites [3].

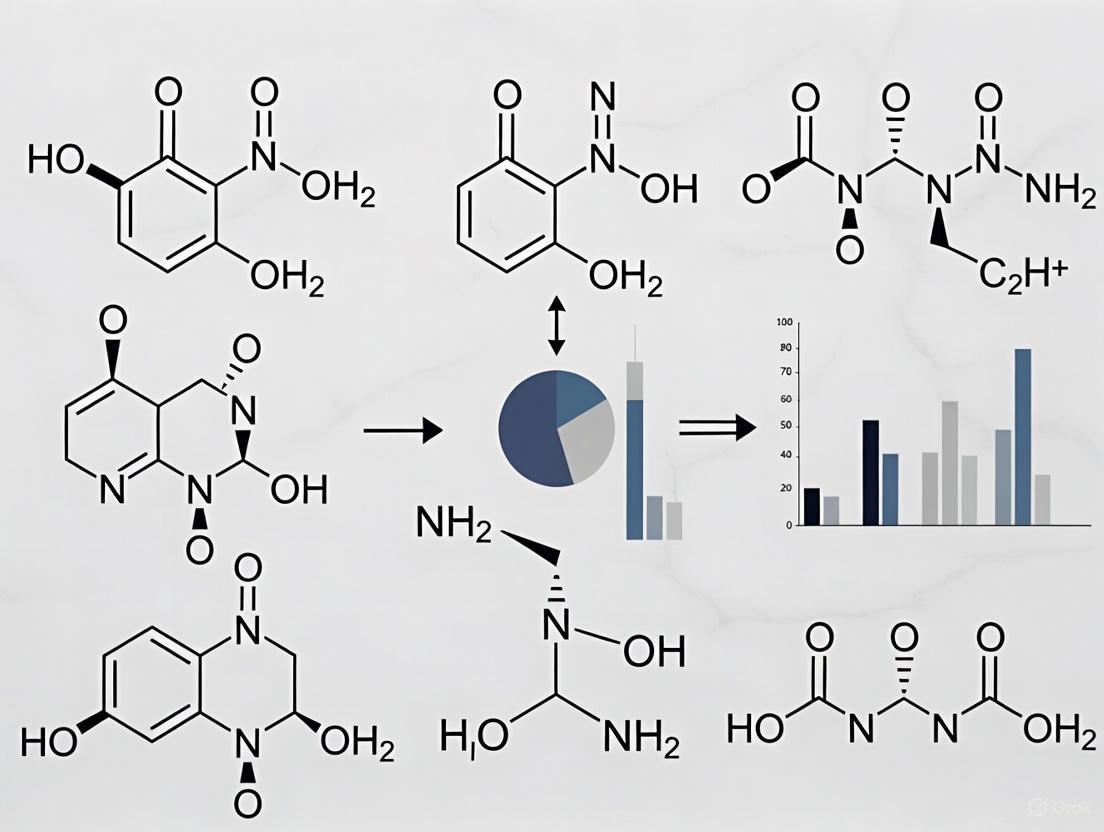

Diagram 1: Covalent Probe Mechanism

Major Applications in Biological Research

Target Identification and Validation

Chemical probes serve indispensable roles in target identification and validation, particularly through chemical proteomics approaches [4] [2]. In these applications, probes are designed with additional handles (e.g., biotin, fluorescent tags, or photoaffinity groups) that enable isolation or visualization of interacting proteins [5] [4]. For example, honokiol-based photoaffinity probes have been employed to identify cellular targets of this natural product, revealing that approximately 62% of captured proteins have established roles in cancer, providing mechanistic insights into its antitumor properties [5].

Modern chemical proteomics leverages covalent probe technology combined with advanced mass spectrometry to comprehensively map protein-small molecule interactions in native cellular environments [4]. These approaches can identify both anticipated on-target engagements and unexpected off-target interactions that might contribute to phenotypic effects or toxicity [4]. The resulting interaction maps provide critical validation for putative therapeutic targets and help prioritize candidates for drug development efforts [2].

Imaging and Diagnostic Applications

Enzyme-targeted chemical probes have revolutionized molecular imaging by enabling real-time visualization of enzymatic activity in living systems [3]. These probes typically incorporate three key elements: a targeting moiety (substrate or inhibitor), a linker, and a reporter group that generates a detectable signal upon enzymatic interaction [3]. Advanced probe designs feature "turn-on" mechanisms where fluorescence is quenched until enzymatic cleavage releases the active fluorophore, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratios in biological environments [3].

The applications span multiple imaging modalities, including fluorescence imaging with NIR and NIR-II fluorophores for improved tissue penetration, PET and SPECT tracers for highly sensitive quantitative imaging, MRI contrast agents that alter relaxivity upon enzymatic activation, and mass cytometry reagents that enable highly multiplexed analysis of enzyme activities in single cells or tissues [3]. These diverse imaging approaches collectively provide unprecedented insights into enzyme function in health and disease, facilitating early diagnosis, disease monitoring, and precision medicine applications [3].

Table 2: Chemical Probe Applications by Modality

| Application Domain | Probe Type | Key Characteristics | Readout Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Photoaffinity probes, Covalent probes | Covalent capture, Minimal target perturbation | Mass spectrometry, Affinity purification |

| Cellular Imaging | Activatable fluorescent probes | Turn-on fluorescence, Substrate-based design | Fluorescence microscopy, Flow cytometry |

| In Vivo Imaging | NIR/PET/MRI probes | Deep tissue penetration, High sensitivity | Optical imaging, PET, SPECT, MRI |

| Multiplexed Analysis | Metal-tagged probes | Minimal spectral overlap, High parameter counting | Mass cytometry (CyTOF), Imaging mass cytometry |

| Theranostics | Activatable drug conjugates | Combined imaging and therapy, Stimuli-responsive | Multiple modalities with drug release |

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Chemical Proteomics Workflow

Chemical proteomics represents a powerful experimental approach for target identification using chemical probes. The standard workflow begins with probe design and synthesis, incorporating photoaffinity groups for covalent capture and affinity handles (e.g., alkyne tags) for subsequent bioorthogonal conjugation [5] [4]. Live cells are treated with the probe, followed by UV irradiation to crosslink the probe to interacting proteins [5]. Cells are then lysed, and probe-bound proteins are conjugated to capture reagents (e.g., biotin-azide via click chemistry) and isolated using affinity purification (e.g., streptavidin beads) [5].

The captured proteins are digested, and resulting peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [5] [4]. Quantitative proteomics approaches (e.g., SILAC, TMT, or label-free quantification) enable discrimination of specific binding partners from non-specific interactions by comparing probe-treated samples to appropriate controls [5]. Finally, bioinformatic analysis identifies proteins significantly enriched in probe-treated samples, generating a comprehensive map of protein-probe interactions [5].

Diagram 2: Chemical Proteomics Workflow

Cellular Target Engagement Assays

Confirming that a chemical probe engages its intended target in a cellular context is essential for establishing its utility as a research tool. The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) has emerged as a powerful method for assessing cellular target engagement by measuring the stabilization of proteins against thermal denaturation upon ligand binding [5] [1]. In this approach, probe-treated and control cells are heated to different temperatures, followed by cell lysis and separation of soluble (native) protein from insoluble (denatured) protein [5]. The remaining soluble target protein is quantified by immunoblotting or other detection methods, with increased thermal stability indicating direct probe binding [5].

Alternative approaches for confirming cellular target engagement include drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS), which assesses protease resistance upon ligand binding, and cellular imaging techniques using fluorescently tagged probes [3]. For kinase targets, phospho-proteomic profiling can demonstrate on-target effects by revealing changes in downstream signaling pathways consistent with specific kinase inhibition [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The growing importance of chemical probes in biomedical research has stimulated development of curated resources to help researchers identify high-quality probes for their experiments. The Chemical Probes Portal (www.chemicalprobes.org) represents a vital community resource featuring expert reviews and evaluations of chemical probes [6]. This platform provides guidance on selecting the most suitable probes for specific applications and shares best practices for their use [6]. As of 2025, the Portal contains information on over 1,163 probes and more than 1,600 expert reviews, making it an essential starting point for researchers seeking chemical probes [6].

Additional important resources include canSAR, an integrated knowledgebase that combines chemical, biological, and structural data to inform target selection and probe discovery, and Probe Miner, which provides objective, quantitative assessment of chemical probes based on publicly available data [7]. These resources collectively support the "Target 2035" initiative, which aims to develop a high-quality chemical probe for every human protein by 2035 [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Probe Platforms | Photoaffinity probes, Activity-based probes | Target identification, Enzyme activity profiling | Warhead reactivity, Cross-linking efficiency |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Alexa Fluor dyes, Cy dyes, FITC | Cellular imaging, Localization studies | Photostability, Brightness, Spectral overlap |

| Affinity Handles | Biotin, Alkyne tags, HIS tags | Target isolation, Pull-down experiments | Size impact on binding, Elution conditions |

| Control Compounds | Inactive structural analogs, Enantiomers | Specificity controls, Background determination | Structural similarity, Synthetic accessibility |

| Detection Systems | HRP conjugates, Streptavidin beads | Signal amplification, Target capture | Non-specific binding, Detection sensitivity |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

AI and Computational Advances

Artificial intelligence is increasingly transforming chemical probe discovery and optimization [3]. AI approaches now support multiple aspects of probe development, from structure prediction and binding affinity modeling to the generation of novel chemical scaffolds with favorable pharmacological properties [3]. Machine learning models trained on large-scale chemical biology datasets can predict target engagement, selectivity profiles, and even cellular activity, significantly accelerating the probe design cycle [3]. These computational approaches are particularly valuable for exploring under-represented regions of chemical space and identifying starting points for probe development against challenging targets [8].

The integration of AI with structural biology and chemical proteomics has created powerful feedback loops wherein experimental data improves predictive models, which in turn design better probes [3]. For example, machine learning analysis of chemical proteomics data has enabled identification of patterns predicting phospholipidosis induction by small molecules, highlighting how AI can address complex pharmacological properties beyond simple target affinity [7]. As these approaches mature, they promise to democratize access to high-quality chemical probes for even the most challenging protein targets.

Theranostic Probes and Clinical Translation

A particularly promising frontier involves the development of enzyme-activated theranostic systems that couple imaging with targeted drug release [3]. These integrated probes can visualize disease-associated enzymatic activity while simultaneously delivering therapeutic payloads specifically at sites of interest [3]. This approach represents a significant expansion of the functional scope of chemical probes beyond basic detection toward integrated diagnostic and therapeutic applications [3].

The clinical translation of enzyme-targeted probes is already underway, with several probes now in clinical trials or approved for human use [3]. This transition exemplifies the success of translational chemical biology and demonstrates how fundamental chemical tools can directly impact patient care [3]. As probe technologies continue to evolve, we can anticipate growing clinical applications in areas such as intraoperative guidance, patient stratification, and treatment monitoring, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine through chemical innovation [3].

In the pipeline from basic biological research to clinical therapy, chemical probes and drugs represent distinct classes of small molecules with fundamentally different purposes and requirements. Within the context of target identification and validation research, this distinction is critical: chemical probes are primarily tools for understanding biological mechanisms and interrogating protein function, whereas drugs are optimized therapeutic agents designed for safe and effective patient treatment. The confusion between these categories can lead to inappropriate compound usage, misinterpreted experimental results, and costly research inefficiencies. Research indicates that the continued use of poorly characterized probes has generated "research of suspect conclusions, at great cost to the taxpayer and other funders, to scientific careers and to the reliability of the scientific literature" [1]. This guide provides researchers with a structured framework for distinguishing these molecular tools, selecting appropriate reagents, and applying rigorous validation methodologies to ensure research quality and reproducibility.

Fundamental Characteristics: A Comparative Analysis

Core Definitions and Purpose

Chemical Probes: A chemical probe is defined as "a selective small-molecule modulator of a protein's function that allows the user to ask mechanistic and phenotypic questions about its molecular target in biochemical, cell-based or animal studies" [1]. These reagents are engineered primarily for target validation and pathway elucidation, serving as precision tools to disrupt specific protein functions in experimental settings. Their unique value lies in their ability to complement genetic approaches like CRISPR and RNAi by enabling rapid, reversible, and dose-dependent inhibition in virtually any cell type [1].

Drug Compounds: In contrast, drugs are small molecules "optimized for in vivo use" with requirements for being "safe and effective" in human therapeutic applications [9]. While drugs may potentially engage multiple targets (polypharmacology) to achieve clinical effects, their development prioritizes human safety, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic efficacy over mechanistic specificity [1].

Key Differentiating Characteristics

The table below summarizes the principal distinctions between chemical probes and drug compounds across critical parameters:

Table 1: Essential Characteristics of Chemical Probes Versus Drug Compounds

| Characteristic | Chemical Probes | Drug Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Investigate biology, validate targets [1] | Treat human diseases safely and effectively [9] |

| Mechanism of Action | Must be clearly defined and selective [9] | May not be fully defined; polypharmacology may be beneficial [1] |

| Selectivity Requirements | High selectivity (>30-fold against related targets) essential [1] | Selectivity desirable but not always necessary for efficacy |

| Property Optimization | Optimized for potency and selectivity in experimental models [1] | Optimized for human pharmacokinetics, safety, and stability [9] |

| Availability | Freely available with open data sharing [9] | Often restricted due to intellectual property concerns [9] |

| Negative Controls | Should have structurally related inactive analogs [9] [1] | Typically lack dedicated negative control compounds |

For chemical probes, quality is paramount and defined by specific metrics. Experts recommend that high-quality probes should demonstrate "in vitro potency at the target protein of <100 nM, possess >30-fold selectivity relative to other sequence-related proteins of the same target family," be profiled against standard pharmacologically relevant off-target panels, and demonstrate "on-target effects in cells at <1 μM" [1].

Experimental Design and Validation Strategies

Minimum Characterization Standards for Probes

Robust target validation research requires comprehensive probe characterization through orthogonal methodologies:

- Cellular Target Engagement: Demonstrate direct binding to the intended target in physiological environments using technologies such as Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) or chemical proteomics [1].

- Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate against extended panels of related targets and pharmacologically relevant off-targets (e.g., kinases, GPCRs, ion channels) [1].

- Dose-Response Relationships: Establish clear concentration-dependent effects with minimal off-target activity at effective concentrations.

- Rescue Experiments: Confirm phenotype reversal through genetic complementation or orthogonal approaches.

Practical Workflow for Probe Validation

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to probe validation and application in target identification research:

Probe Validation Workflow: This systematic approach ensures rigorous characterization before biological application.

The Critical Role of Negative Controls

A defining feature of high-quality chemical probes is the availability of "an inactive close analog of the compound to serve as a negative control" [1]. These matched compounds, often termed "inactive control analogs" or "matched molecular pairs," possess nearly identical chemical structures but lack activity against the intended target. Their proper use enables researchers to:

- Distinguish target-specific effects from non-specific compound activities

- Control for potential off-target effects shared by the structural class

- Verify that observed phenotypes result from intended target modulation

- Increase experimental robustness and conclusion validity

Several established platforms provide expert-guided probe selection to support rigorous research:

Table 2: Key Resources for Chemical Probe Selection and Validation

| Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Expert-reviewed probe evaluations [6] | Community ratings, selectivity assessments, usage guidelines | www.chemicalprobes.org [6] |

| Probe Miner | Data-driven probe assessment [10] [11] | Quantitative scoring across >1.8 million compounds for 2,220 human targets [10] | Public online resource |

| Structural Genomics Consortium | Open-source probe development | Potency <100 nM, >30-fold selectivity, cell activity <1 μM [1] | Collaborative initiative |

The Chemical Probes Portal specifically aims to "support the biological research community to select the best chemical tools such as inhibitors, activators and degraders" through expert reviews and evaluations [6]. This resource addresses the critical need for centralized, authoritative guidance on probe quality.

Common Artifacts and Pitfalls in Probe Usage

Researchers must remain vigilant about compound classes with documented reliability issues:

- Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS): These molecules contain structural motifs that "bind proteins non-selectively, generating spurious activity readings, or disrupting cellular membranes" [12]. Examples include certain flavones and epigallocatechin-3-gallate, which continue to be used despite their promiscuous behavior [1].

- Inappropriate Probe Concentrations: Using compounds at concentrations significantly above their demonstrated selective range (e.g., mM concentrations of LiCl for GSK3β inhibition) frequently produces off-target effects that compromise data interpretation [1].

- Species-Specific Activity Differences: Probes like WY14643 (PPARα) show "significant activity difference in human versus murine orthologs," potentially confounding translational studies [1].

The Developmental Pathway: From Probe to Drug

Transitioning Chemical Tools to Therapeutics

The relationship between probes and drugs represents a developmental continuum rather than a binary distinction. High-quality probes can serve as valuable starting points for drug discovery campaigns, as exemplified by BET bromodomain inhibitors including (+)-JQ1, which enabled both fundamental research and subsequent clinical development [1]. The diagram below illustrates this developmental trajectory:

Probe to Drug Pipeline: Chemical probes enable biological validation before lead optimization for clinical development.

Property Optimization Priorities

The transition from probe to drug requires significant molecular redesign to address different priority requirements:

- Chemical Probes: Prioritize target potency, selectivity, and mechanism of action clarity. Properties like aqueous solubility are important but may be secondary to pharmacological specificity [12].

- Drug Compounds: Must satisfy stringent requirements for "molecular weight, lipophilicity, stability," defined crystal structures, and economic synthesis [9]. Oral bioavailability, metabolic stability, and toxicological profiles become paramount considerations.

This distinction explains why many high-quality probes are unsuitable as drug candidates without substantial optimization, and conversely, why many effective drugs would function poorly as mechanistic probes due to their polypharmacology.

The distinction between chemical probes and drugs extends beyond semantic differences to fundamentally impact research quality and therapeutic development. Researchers must select molecular tools aligned with their experimental goals: chemical probes for target validation and mechanistic studies, drug compounds for therapeutic effect modeling. By leveraging community resources like the Chemical Probes Portal, implementing rigorous validation workflows, employing appropriate negative controls, and understanding the limitations of different compound classes, scientists can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their findings. As chemical biology continues to evolve, this disciplined approach to probe selection and application will remain essential for generating robust biological insights and enabling successful translation to clinical applications.

In the field of chemical biology and drug discovery, the precise identification of a small molecule's cellular target is a fundamental challenge. Target identification research aims to bridge the gap between observing a phenotypic effect of a small molecule and understanding its specific mechanism of action, which is crucial for validating therapeutic targets and optimizing lead compounds [13]. Within this research paradigm, chemical probes are indispensable tools. Defined as small molecules designed to selectively bind to and alter the function of a specific protein target, high-quality chemical probes must meet stringent criteria, including potency (typically with a Kd < 100 nM), cellular activity (EC50 < 1 µM), and exceptional selectivity (often >30-fold over related proteins) [14] [15].

The effectiveness of these probes, particularly in advanced chemoproteomic techniques like Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP), hinges on a modular, three-component design [16]. ABPP generates global maps of small molecule-protein interactions in native biological systems, thereby expanding the druggable proteome and enabling the study of historically "undruggable" target classes [17]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core components of a chemical probe—the reactive group (warhead), the linker, and the reporter tag—framed within the context of target identification research.

The Core Architectural Components of a Probe

The canonical structure of a probe, particularly an Activity-Based Probe (ABP), is tripartite. These components work in concert to ensure specific labeling, efficient detection, and isolation of the target protein(s) [16].

Reactive Group (Warhead)

The reactive group, or warhead, is the moiety responsible for covalently and irreversibly binding to the target protein. Its design is dictated by the specific class of target protein and the mechanism of labeling.

- Activity-Based Probes (ABPs): The warhead in an ABP is typically an electrophilic group designed to covalently modify nucleophilic residues (e.g., serine, cysteine) in the active site of mechanistically related classes of enzymes. This design allows ABPs to selectively label active enzymes, reporting on their functional state within a complex proteome [16]. For example, early ABPs targeted serine hydrolases using fluorophosphonate (FP) warheads [17].

- Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs): For AfBPs, the warhead consists of a highly selective target-binding motif (often derived from a known inhibitor or ligand) coupled with a photo-activatable group (e.g., a diazirine or benzophenone). Upon irradiation with UV light, this photo-affinity group generates a highly reactive intermediate (e.g., a carbene or diradical) that forms a covalent bond with nearby amino acid residues, "trapping" the interaction [16] [13]. This approach is useful for proteins that lack a nucleophilic catalytic residue.

The choice of warhead is critical for determining the probe's selectivity and applicability. The table below summarizes common warheads and their primary targets.

Table 1: Common Reactive Groups and Their Applications in Probe Design

| Reactive Group Type | Specific Examples | Target Residue/Protein Class | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophilic (for ABPs) | Fluorophosphonates (FP) | Serine (in Serine Hydrolases) | Mechanism-based; labels active enzymes [16]. |

| Carbamates, Ureas | Serine Hydrolases | Tailored reactivity for specific enzyme families [17]. | |

| Iodoacetamide | Cysteine | Broadly reacts with cysteines; informs on redox state and ligandable pockets [17]. | |

| Sulfonate esters, Epoxides | Various nucleophiles | Used in scout fragments to survey ligandability [17]. | |

| Photo-activatable (for AfBPs) | Aryldiazirines (e.g., Trifluoromethyl phenyl diazirine) | Any proximal residue | Forms a reactive carbene upon UV irradiation; preferred for its small size and stability [13]. |

| Benzophenones | Any proximal residue | Forms a diradical upon UV irradiation; can be less efficient but is well-characterized [13]. | |

| Phenylazides | Any proximal residue | Forms a nitrene upon UV irradiation; can be less stable than diazirines [13]. |

Linker

The linker region connects the reactive group to the reporter tag and serves multiple essential functions:

- Spatial Separation: It provides sufficient distance between the warhead and the bulky reporter tag to prevent steric hindrance that could impede the warhead's access to its binding pocket.

- Modulating Reactivity and Selectivity: The chemical composition and length of the linker can fine-tune the reactivity of the warhead and, in some cases, contribute to target selectivity by occupying adjacent regions of the binding site [16].

- Chemical Handle: The linker often incorporates functional groups to enable the subsequent conjugation of the reporter tag via bioorthogonal chemistry, such as click reactions.

A critical application of the linker is in photoaffinity tagging, where the linker connects the target-binding motif to the photoreactive group, allowing for covalent cross-linking upon UV light activation [13].

Reporter Tag

The reporter tag is the moiety that enables the detection, visualization, and/or purification of the probe-labeled proteins. The choice of tag is a balance between detectability and the practicalities of the experiment, particularly cell permeability.

- Direct Tags: These include fluorophores (e.g., fluorescein, TAMRA) for direct visualization via SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence scanning or microscopy, and biotin for affinity purification using streptavidin-coated beads followed by identification with mass spectrometry [16] [13].

- Bioorthogonal Handles (Indirect Tagging): For experiments in living cells or organisms, large tags like fluorophores or biotin can impede cell permeability. A highly effective strategy is to use small, inert functional groups like alkynes or azides as "latent" handles. After the probe has labeled its target within the native biological system, a reporter tag (e.g., a fluorophore or biotin) is conjugated to this handle via a bioorthogonal reaction, most commonly the copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), or "click chemistry" [16]. This two-step protocol greatly enhances flexibility and cellular application.

Table 2: Common Reporter Tags and Their Applications

| Reporter Tag | Detection/Purification Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biotin | Streptavidin pull-down + LC-MS/MS; Streptavidin blotting | High affinity interaction; enables strong enrichment for MS-based target identification [16] [13]. | Harsh denaturing conditions (e.g., boiling with SDS) often needed for elution, which can damage proteins [13]. |

| Fluorophore | In-gel fluorescence scanning; Fluorescence microscopy | Enables rapid, comparative profiling; allows spatial visualization in cells [16]. | Limited resolution (a single band may contain multiple proteins); less suited for definitive target identification. |

| Alkyne/Azide | Click chemistry conjugation to a desired tag (biotin/fluorophore) followed by standard methods. | Superior cell permeability; high flexibility—a single probe can be paired with multiple tags for different applications [16]. | Requires an additional chemical reaction step after biological labeling. |

The logical and structural relationship between these three core components is illustrated below.

Experimental Protocol: Competitive ABPP for Target Engagement

Competitive ABPP is a key experimental workflow for validating target engagement and screening for new inhibitors in a native proteomic context [17] [16]. The following protocol details the steps for a gel-based competitive ABPP experiment.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Competitive ABPP

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probe (ABP) | The central tool; contains a reactive warhead, linker, and a direct fluorophore tag (e.g., BODIPY-FP) for in-gel visualization. |

| Test Compound(s) | The small molecule(s) being evaluated for their ability to compete with the ABP for binding to the target protein(s). |

| Proteome Source | A complex biological sample containing the target proteins, such as cell lysates, tissue homogenates, or purified protein fractions. |

| Lysis Buffer | A buffer suitable for maintaining protein integrity and activity, often containing detergents, salts, and protease inhibitors. |

| SDS-PAGE Gel | For separating proteins by molecular weight after the labeling reaction. |

| Fluorescence Scanner | A specialized imager for detecting the fluorescently labeled proteins in the gel. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the proteome of interest (e.g., lysate from cultured cells). Determine the protein concentration and aliquot equal amounts into microcentrifuge tubes.

- Pre-incubation with Compound: Pre-treat the proteome aliquots with varying concentrations of the test compound or with a DMSO vehicle control. Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 30 minutes) at a physiologically relevant temperature (e.g., 37°C) to allow the compound to bind to its target.

- ABP Labeling: Add the fluorescent ABP to each sample. Incubate further to allow the ABP to label any remaining accessible binding sites on the target proteins.

- Reaction Termination and Denaturation: Stop the labeling reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating the samples (e.g., 95°C for 5 minutes) to denature the proteins.

- Protein Separation: Load the denatured samples onto an SDS-PAGE gel and run the gel to separate proteins by molecular weight.

- Fluorescence Visualization: Scan the gel using a fluorescence scanner to detect the fluorescent signal from the ABP-labeled proteins.

- Data Analysis: Compare the fluorescence intensity of labeled protein bands between the compound-treated and DMSO control samples. A dose-dependent decrease in fluorescence intensity at a specific band indicates that the test compound successfully competes with the ABP for binding to that particular protein, confirming target engagement.

The workflow for this competitive ABPP protocol is visualized in the following diagram.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The modular design of chemical probes has enabled their application far beyond simple enzyme inhibition. ABPP has been instrumental in discovering ligands that operate through atypical modes of action, including the disruption and stabilization of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and allosteric regulation [17]. Furthermore, the principles of probe design have been adapted for new therapeutic modalities.

A prime example is the development of PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs). These bifunctional molecules can be viewed as an advanced application of probe concepts. A PROTAC consists of a target protein-binding ligand (which functions similarly to the affinity motif of an AfBP) connected via a linker to an E3 ubiquitin ligase recruiter. This three-component system forms a ternary complex that induces ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein by the proteasome [14]. This modality expands the target space to proteins traditionally considered "undruggable" by conventional inhibitors and can impart striking selectivity.

The tripartite architecture of reactive group, linker, and reporter tag forms the foundation of effective chemical probe design for target identification. The strategic selection and integration of these components enable researchers to directly measure small molecule-protein interactions within the complex native environment of the cell. As exemplified by ABPP and emerging technologies like PROTACs, this modular framework provides a versatile and powerful platform for illuminating the functional proteome, validating therapeutic targets, and ultimately advancing drug discovery for the benefit of human health.

The Critical Role of Selectivity and Potency in Probe Design

In the realm of chemical biology and drug discovery, chemical probes represent indispensable tools for deciphering protein function and validating therapeutic targets. These highly characterized small molecules are designed to selectively bind to and modulate specific proteins within complex biological systems, thereby enabling researchers to establish causal relationships between a protein's activity and phenotypic outcomes [14] [15]. The utility of these probes extends across multiple domains—from basic research investigating protein function in cells and organisms to applied drug discovery efforts where they facilitate target validation and biomarker identification [15].

The evolution of chemical probe criteria represents a scientific response to decades of confounding research results generated by poorly characterized tool compounds. Historically, the use of weak and non-selective small molecules has produced an abundance of erroneous conclusions in the scientific literature, necessitating the development of stringent guidelines to ensure probe quality [14]. This whitepaper examines the critical importance of selectivity and potency as foundational pillars of high-quality chemical probe design, providing researchers with a technical framework for developing and evaluating these essential research tools within the context of modern target identification research.

Defining Quality: Essential Criteria for Chemical Probes

Established Community Standards

The scientific community has developed consensus criteria to define high-quality chemical probes suitable for investigating protein function. These "fitness factors" provide essential guidance for biologists who may be less familiar with the potential limitations of compounds marketed as chemical probes [14]. According to these established standards, chemical probes must demonstrate:

- High potency: Typically defined as IC50 or Kd < 100 nM in biochemical assays and EC50 < 1 μM in cellular assays [14] [15]

- Excellent selectivity: Generally accepted as >30-fold selectivity within the protein target family, alongside extensive profiling of off-targets outside the immediate protein family [14] [15]

- Strong evidence of on-target engagement: Demonstrable modulation of the intended target in cellular and organismal models [14]

- Favorable physicochemical properties: Exclusion of highly reactive promiscuous molecules, including nonspecific electrophiles, redox cyclers, chelators, and colloidal aggregators that modulate biological targets through undesirable mechanisms of action [14]

Additional Validation Tools

Beyond these core criteria, best practices in the field recommend two additional experimental controls to strengthen conclusions drawn from chemical probe studies. First, the use of inactive analogues—structurally similar compounds that lack activity against the primary target—helps establish correlations between on-target engagement and observed phenotypes [14]. Second, employing a structurally distinct chemical probe targeting the same protein provides orthogonal validation, increasing confidence that observed effects genuinely result from modulation of the intended target rather than off-target effects [14] [15].

Table 1: Minimum Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

| Parameter | Requirement | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Potency | IC50 or Kd < 100 nM | Dose-response curves in purified system |

| Cellular Potency | EC50 < 1 μM | Cellular activity assays |

| Selectivity | >30-fold within target family | Broad profiling (e.g., kinome, GPCR panels) |

| Cellular Target Engagement | Direct binding measurement in live cells | BRET, FRET, CETSA, or other direct binding assays |

| Specificity | Minimal off-targets outside primary family | Proteome-wide profiling (e.g., chemoproteomics) |

The Critical Importance of Selectivity

Historical Context and Modern Solutions

The systematic evaluation of small-molecule tool compounds began with pioneering work on kinase inhibitors in the year 2000, which revealed that compounds frequently assumed to be specific for a single target often inhibited additional kinases, sometimes even more potently than their presumed primary target [14]. This recognition sparked the development of the first guidelines for selecting high-quality small molecule inhibitors to study protein kinase function and eventually expanded to encompass chemical probes for diverse protein classes [14].

Modern approaches to ensuring selectivity involve extensive profiling against related proteins within the same family. For example, for kinase inhibitors, this typically means screening against large panels of kinases (often hundreds) to identify potential off-target interactions [15]. Similarly, probes for epigenetic targets like bromodomains should be profiled against other bromodomain-containing proteins to ensure family selectivity [14]. The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) has established rigorous standards in this domain, requiring >30-fold selectivity relative to closely related family member proteins for their chemical probes [15].

Advanced Selectivity Mechanisms

Recent innovations in chemical probe modalities have introduced novel mechanisms for achieving exceptional selectivity. PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) and other protein degraders represent a particularly powerful approach, as they can endow striking selectivity even when the protein-target-binding arm of the molecule exhibits some level of off-target activity [14]. This phenomenon occurs because protein degraders require the formation of a productive ternary complex between the target protein, the degrader molecule, and an E3 ubiquitin ligase to induce ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. The requirement for this specific three-way interaction creates an additional selectivity filter beyond simple binding affinity [14].

Covalent chemical probes offer another strategy for enhancing selectivity through targeted engagement with unique nucleophilic residues (such as cysteine) within a protein's binding pocket. The development of reversible covalent JAK3 inhibitors exemplifies this approach, where researchers targeted a specific noncatalytic cysteine residue present in JAK3 but absent in other JAK family members, resulting in exceptional selectivity across the kinome [15].

Assessing Potency Across Experimental Systems

Defining Potency Parameters

Potency represents a multidimensional parameter in chemical probe development, requiring characterization across different experimental contexts:

- Biochemical potency: Measured in purified systems using the isolated target protein, typically reported as IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) or Kd (equilibrium dissociation constant) with an expectation of <100 nM [14] [15]

- Cellular potency: Determined in live cells, reported as EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) with an expectation of <1 μM [14] [15]

- Cellular target engagement: Direct measurement of binding to the intended target in its native cellular environment, often employing techniques like bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) or cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) [15]

The critical relationship between biochemical and cellular potency cannot be assumed, as cellular permeability, efflux mechanisms, and protein binding can dramatically impact a compound's effective concentration at its intracellular site of action.

The Pharmacological Audit Trail

The concept of the Pharmacological Audit Trail provides a systematic framework for establishing confidence in chemical probe experiments [14]. This approach requires researchers to demonstrate a clear chain of evidence connecting:

- Exposure: Adequate cellular or tissue concentration of the probe

- Target engagement: Direct binding to the intended protein target

- Pharmacodynamic effect: Modulation of the target's biochemical activity

- Phenotypic outcome: Resulting changes in cellular or organismal phenotype

This framework ensures that observed biological effects can be confidently attributed to modulation of the intended target rather than off-target mechanisms [14] [15].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Characterizing Chemical Probes

| Characterization Type | Key Methodologies | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Potency | Fluorescence polarization, FRET, TR-FRET, ALPHAscreen, radioligand binding | Affinity for purified target protein |

| Cellular Potency | Cell-based functional assays (reporter gene, second messenger, pathway activation) | Functional activity in physiological context |

| Target Engagement | BRET, FRET, CETSA, cellular residence time assays | Direct binding to target in live cells |

| Selectivity Profiling | Panels (kinase, GPCR, etc.), chemoproteomics, affinity purification mass spectrometry | Identification of on- and off-target interactions |

| Structural Characterization | X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM | Molecular basis of binding and selectivity |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Validation

Target Engagement Assays

Demonstrating direct binding to the intended target in live cells represents one of the most critical validation steps for chemical probes. Simon and colleagues have advocated that "direct measurements of target engagement should become standard practice in the development of new chemical probes" [15]. The most valuable target engagement assays are those that report directly on the interaction between the chemical probe and target protein rather than distal measurements, and that can measure probe selectivity against related proteins in the cellular environment [15].

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) Target Engagement Assay:

This protocol describes a live-cell competitive binding assay used to validate the JAK3 reversible covalent probe FM-381 [15]:

- Construct design: Generate a fusion protein of the target (e.g., JAK3) with a luciferase donor (e.g., NanoLuc).

- Tracer design: Develop a fluorescently-labeled analog of the chemical probe or a known binder that competes with the probe for binding.

- Cell preparation: Transfect cells with the fusion construct and seed in assay-compatible plates.

- Equilibrium binding: Treat cells with the chemical probe at varying concentrations alongside a fixed concentration of the tracer compound.

- Signal detection: Measure BRET signal between the luciferase-tagged target and fluorescent tracer.

- Data analysis: Calculate apparent affinity (Kd) from competitive displacement curves and determine cellular residence time through real-time washout experiments.

This approach confirmed potent apparent intracellular affinity for JAK3 (approximately 100 nM) and demonstrated durable but reversible intracellular binding in real-time cellular residence time studies [15].

Chemoproteomic Selectivity Profiling

Comprehensive selectivity assessment extends beyond the target family to potential off-targets across the entire proteome. Chemoproteomics has emerged as a powerful technique for identifying specific protein targets and off-targets of covalent chemical probes [4].

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) Protocol:

- Probe design: Incorporate a latent electrophile (e.g., acrylamide) and a detection handle (e.g., alkyne) into the chemical probe structure.

- Cell treatment: Incubate live cells with the chemical probe across a range of concentrations and time points.

- Click chemistry: After cell lysis, conjugate the alkyne-handle to a reporter tag (e.g., biotin-azide) using copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition.

- Streptavidin enrichment: Capture biotinylated proteins using streptavidin beads and wash extensively to remove non-specific binders.

- On-bead digestion: Digest captured proteins with trypsin while still bound to beads.

- LC-MS/MS analysis: Identify captured peptides by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

- Data processing: Use quantitative proteomics to compare probe-treated samples to vehicle controls, identifying specifically enriched protein targets.

This approach has proven enormously powerful in target and off-target identification for covalent probes, as exemplified by reagents that profile palmitoylation, ligand identification for monoacylglycerol lipids, and photoaffinity profiling of pharmacophores for kinase inhibitors [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Chemical Probe Selection and Validation

| Resource | Description | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Expert-curated resource for quality chemical probes | 4-star rating system by Scientific Expert Review Panel; comments on appropriate use and limitations | https://www.chemicalprobes.org [14] [15] |

| SGC Chemical Probes | Open-access chemical probes developed by Structural Genomics Consortium | Meets stringent criteria: <100 nM potency, >30-fold selectivity, cell-active | https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes [14] [15] |

| Probe Miner | Computational platform for statistically-based ranking of chemical tools | Mines bioactivity data from >1.8 million small molecules and >2200 human targets | https://probeminer.icr.ac.uk [14] |

| OpnMe Portal | Boehringer Ingelheim's platform for high-quality small molecules | Provides in-house-developed compounds freely or via scientific research submissions | https://opnme.com [14] |

Visualization of Chemical Probe Development Workflow

Diagram 1: Chemical Probe Development Workflow

Visualization of Pharmacological Audit Trail

Diagram 2: Four-Pillar Pharmacological Audit Trail

The rigorous application of selectivity and potency standards in chemical probe development represents a critical foundation for advancing biological knowledge and drug discovery. The establishment of community guidelines, sophisticated validation methodologies, and curated resources has transformed the landscape of chemical tool development, enabling researchers to draw more reliable conclusions about protein function. As new modalities continue to emerge—including PROTACs, molecular glues, and covalent probes—the fundamental principles of potency and selectivity remain paramount. By adhering to these standards and utilizing the experimental frameworks outlined in this technical guide, researchers can ensure that their work with chemical probes generates robust, reproducible, and biologically meaningful results that accelerate scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

Chemical genetics is a powerful research paradigm that uses small molecules to perturb and elucidate biological systems. Mirroring the principles of classical genetics, it investigates gene function and protein activity by observing the phenotypic consequences of these perturbations. Small molecules, whether synthetic or derived from natural sources, function as precise tools to modulate protein function, offering a reversible and tunable means to dissect complex biological pathways. This approach is particularly valuable in target identification research, where establishing a causal link between a molecular target and a cellular phenotype is paramount for validating potential therapeutic targets. The field is broadly divided into two complementary strategies: forward chemical genetics, which begins with a phenotypic observation, and reverse chemical genetics, which starts with a specific protein of interest [18] [19].

The core value of chemical genetics in probe discovery lies in its ability to "prevalidate" a biological target. A phenotypic screen identifies small molecules that effectively modulate a disease-relevant process, implying that the protein target of that molecule is both druggable and critical to the pathway. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and analytical tools that underpin forward and reverse chemical genetics, framing them within the context of developing chemical probes for target identification.

Core Principles: Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics

The fundamental distinction between forward and reverse chemical genetics lies in the starting point of the investigation. The relationship and workflow of these two approaches are illustrated in the diagram below.

Forward Chemical Genetics

The forward approach is analogous to classical forward genetics. It is an unbiased, discovery-driven process that starts with screening a library of small molecules against a cellular or organismal model to identify compounds that induce a specific phenotype of interest. Once a bioactive "hit" compound is found, the subsequent and often most challenging step is to identify its protein target(s). This approach is powerful because it directly links a small molecule to a biological function without preconceived notions about the proteins involved, often revealing novel biology and unexpected therapeutic targets [18] [20]. For example, the immunosuppressants cyclosporine A and FK506 were first identified by their phenotypic effects on T-cell signaling, leading to the subsequent discovery of their targets, calcineurin and FKBP12 [18].

Reverse Chemical Genetics

In contrast, reverse chemical genetics parallels reverse genetics. This is a hypothesis-driven approach that begins with a specific, purified protein target believed to be biologically important. Researchers then screen for small molecules that bind to or modulate the activity of this target. The identified compounds are then introduced into cells or whole organisms to analyze the resulting phenotypic effects. This strategy is target-centric and is frequently used in modern drug discovery programs where a pathogenic protein is already known [18] [19].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Forward and Reverse Chemical Genetics Approaches

| Feature | Forward Chemical Genetics | Reverse Chemical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotypic screen in a complex biological system (cells, organisms) [18] | A specific, purified protein target [19] |

| Philosophy | Unbiased, discovery-based [18] | Hypothesis-driven, target-focused |

| Key Challenge | Target deconvolution - identifying the protein target of the active compound [18] [20] | Phenotypic validation - confirming the compound elicits the desired phenotype in a relevant biological context [19] |

| Primary Screening | Cell-based or organism-based phenotypic assays [20] | In vitro binding or functional assays with the purified target [19] |

| Information Required | No prior knowledge of the target or pathway is needed [18] | Requires prior validation of the protein's role in a biological process [18] |

| Strength | Can reveal novel biology and targets; pre-validates the target in a disease-relevant context [18] | More straightforward; high success rate in finding target-specific binders/inhibitors |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

The successful implementation of chemical genetics relies on robust and reproducible experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key stages in both forward and reverse approaches.

Phenotypic Screening in Forward Chemical Genetics

Phenotypic screens form the foundation of forward chemical genetics. A common and powerful model system for these screens is the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, due to its ease of culturing, genetic tractability, and conservation of core eukaryotic biology. The following protocol describes a quantitative, liquid-based chemical sensitivity assay that provides a more sensitive and rapid alternative to traditional agar-plate methods [21].

Protocol: Quantitative Chemical Sensitivity Assay in Yeast Using 96-Well Plates

- Objective: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC~50~) of a compound against yeast strains of different genotypes.

Principle: This method monitors growth inhibition in response to a chemical by measuring optical density (OD) in a 96-well plate. It generates a quantitative dose-response curve, allowing for precise calculation of IC~50~ values and detection of subtle chemical-genetic interactions [21].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Yeast Strains: Wild-type and mutant strains of interest.

- Compound Library: The small molecules to be screened, dissolved in an appropriate solvent like DMSO.

- 96-Well Plate: Clear, flat-bottom plates.

- Plate Reader: Capable of measuring OD~600~ (with or without continuous shaking capability).

- Liquid Growth Media: Typically YPD or synthetic defined (SD) media.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow yeast strains overnight in liquid media to stationary phase. Dilute the cultures to an OD~600~ of 0.01 in fresh, pre-warmed media. A higher starting OD is used to ensure a uniform lawn of cells and prevent clumping, which can cause variable readings [21].

- Compound Dilution and Dispensing: Prepare a serial dilution of the test compound in the chosen media across a concentration range. Dispense 200 µL of each compound concentration into designated wells of the 96-well plate. Include solvent-only (e.g., DMSO) control wells for normalized growth comparison.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Inoculate each well with 200 µL of the diluted yeast culture (final volume 400 µL, final starting OD~600~ ~0.005). Seal the plate with a breathable membrane to prevent contamination and evaporation. Incubate the plate at 30°C in the plate reader.

- Growth Measurement: Measure the OD~600~ of the culture in each well every 30 minutes for 24-48 hours. If the plate reader lacks an incubation shaker, brief manual shaking before each reading cycle is acceptable [21].

- Data Analysis:

- For each well, plot the OD~600~ over time.

- Calculate the growth rate (slope of the exponential phase) for each compound concentration.

- Normalize the growth rate at each concentration to the growth rate of the solvent-only control.

- Plot the normalized growth rate against the logarithm of the compound concentration.

- Fit a sigmoidal dose-response curve (e.g., using GraphPad Prism) to calculate the IC~50~ value [21].

This liquid-based method is more sensitive, quantitative, and faster than traditional plating assays, and it significantly reduces the amount of chemical required [21].

Target Identification (Target Deconvolution)

Once a compound with an interesting phenotype is identified, the critical next step in forward chemical genetics is target identification. Several direct and indirect methods are employed.

Protocol: Affinity Purification for Target Identification

- Objective: To isolate and identify the direct protein target(s) of a bioactive small molecule.

Principle: The small molecule of interest is immobilized on a solid support (e.g., agarose beads) and used as "bait" to capture binding proteins from a cell lysate. After extensive washing, specifically bound proteins are eluted and identified using mass spectrometry [18].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Immobilized Compound: The bioactive compound derivatized with a chemical handle (e.g., amino or carboxyl group) and covalently linked to chromatography beads.

- Control Beads: Beads coupled with an inactive analog of the compound or with the coupling chemistry alone.

- Cell Lysate: Prepared from a relevant cell line or tissue.

- Chromatography Column: For packing the beads and running the affinity purification.

- Mass Spectrometry System: For protein identification.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation of Immobilized Matrix: Covalently link the compound to activated beads (e.g., NHS-activated Sepharose). A critical control is to prepare beads with an inactive but structurally similar compound [18].

- Incubation with Lysate: Pre-clear the cell lysate by passing it over control beads to remove non-specific binders. Incubate the pre-cleared lysate with the compound-conjugated beads for several hours at 4°C to allow binding.

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively with a buffer containing salt and detergent to remove weakly associated and non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the specifically bound proteins. This can be achieved by:

- Specific Elution: Adding an excess of the free, non-immobilized compound to compete for binding.

- Non-specific Elution: Using a low-pH buffer or SDS-PAGE loading buffer [18].

- Analysis: Separate the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE, followed by staining and in-gel digestion. Alternatively, digest the proteins directly from the bead slurry. Analyze the resulting peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify the bound proteins.

Challenges and Considerations:

- The immobilization process must not destroy the compound's bioactivity.

- Distinguishing specific binders from abundant, non-specific "sticky" proteins requires careful control experiments [18].

- This method may not work for low-abundance or low-affinity targets.

Advanced Profiling: QMAP-Seq for Chemical-Genetic Interaction

Modern chemical genetics leverages high-throughput sequencing for multiplexed analysis. The QMAP-Seq (Quantitative and Multiplexed Analysis of Phenotype by Sequencing) protocol exemplifies this, enabling systematic profiling of chemical-genetic interactions in mammalian cells [22].

Protocol: Overview of QMAP-Seq for Mammalian Cells

- Objective: To quantitatively measure how a panel of genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR knockouts) affects the sensitivity of cells to a library of compounds.

Principle: A pool of isogenic cells, each with a different genetic perturbation marked by a unique DNA barcode, is treated with a compound. The relative abundance of each barcode before and after treatment, quantified by next-generation sequencing (NGS), reveals which genetic perturbations confer sensitivity or resistance to the compound [22].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Barcoded Cell Pool: A pool of cells (e.g., a cancer cell line) engineered with a library of sgRNAs for gene knockout, each bearing a unique barcode sequence.

- Compound Library: The small molecules to be tested.

- Spike-in Standards: A predefined number of cells with unique barcodes added to each sample for absolute quantification [22].

- NGS Library Prep Kit and Sequencing Platform.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pooled Cell Treatment: Induce gene knockout (e.g., with doxycycline for inducible Cas9). Treat the pooled cells with either DMSO (control) or a compound at various doses for a set duration (e.g., 72 hours).

- Cell Lysis and Barcode Amplification: Harvest cells and prepare crude lysates. Spike in a known quantity of standard cells. Perform a PCR amplification using indexed primers to uniquely tag each sample (compound-dose-replicate combination) and amplify the barcode regions.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Pool the PCR products and sequence them on an NGS platform. Use a bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., BEAN-counter) to:

- Demultiplex the samples based on indexes.

- Count the reads for each sgRNA barcode.

- Use the spike-in standards to generate a standard curve and convert read counts into estimated cell numbers.

- Calculate the relative abundance of each barcoded cell line in the treated sample compared to the control [22].

- Interaction Scoring: A significant depletion or enrichment of a specific barcode upon treatment indicates a chemical-genetic interaction (sensitivity or resistance, respectively).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful chemical genetics research requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components of this toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Chemical Genetics

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules for screening; sources include synthetic combinatorial chemistry, natural product extracts, and commercial vendors [20]. | Diversity-oriented synthesis (DOS) aims to create complex, natural product-like libraries. The NIH has initiatives to expand library access for researchers [19]. |

| Immobilization Matrices | Solid supports (e.g., agarose beads) for covalent attachment of small molecules in affinity purification protocols [18]. | The choice of tether and coupling chemistry is critical to preserve the compound's bioactivity and minimize non-specific binding [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Libraries | Pooled collections of guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for targeted gene disruption, each tagged with a unique DNA barcode [22]. | Enables genome-wide or focused (e.g., on a pathway like proteostasis) chemical-genetic interaction screens in mammalian cells [22]. |

| Barcoded Cell Pools | Isogenic cells engineered with a library of genetic perturbations, each identifiable by a unique DNA barcode [22]. | Allows multiplexed screening of hundreds of genetic conditions against thousands of compounds in a single experiment (e.g., via QMAP-Seq) [22]. |

| Spike-in Standards | A predefined mix of cells with known barcodes added in controlled numbers to experimental samples [22]. | Enables absolute quantification of cell numbers from NGS read counts, correcting for PCR and sequencing biases [22]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines (e.g., BEAN-counter) | Software for processing NGS data from barcoded screens into chemical-genetic interaction scores [23]. | Performs quality control, normalization, and calculates interaction Z-scores; essential for handling large-scale screening data [23]. |

Analytical Workflows and Data Interpretation

The raw data from chemical genetics experiments must be processed through robust analytical workflows to yield biological insights. The diagram below outlines the key steps in analyzing a sequencing-based chemical-genetic screen.

The process begins with raw sequencing data from a pooled screen. The data is first demultiplexed, separating the reads based on their unique index tags which correspond to different experimental conditions (e.g., different compounds or doses) [22] [23]. The next step is barcode counting, where the abundance of each sgRNA or strain barcode is quantified. Quality control and normalization are critical; this involves using spike-in standards to convert read counts into estimated cell numbers and correcting for technical artifacts and systematic biases present in large-scale screens [22]. Following normalization, a chemical-genetic interaction score (typically a Z-score) is calculated for each gene-compound pair. This score quantifies whether a genetic perturbation makes cells significantly more sensitive (negative score) or resistant (positive score) to the compound compared to a control [23]. The compilation of these scores for a given compound across all genetic perturbations forms its chemical-genetic interaction profile. This profile serves as a unique fingerprint that can be compared to profiles of compounds with known mechanisms of action to infer the unknown compound's likely target or pathway (MoA) [22]. Similarly, the profile for a gene can be compared to those of genes with known functions to infer its biological role.

Chemical Proteomics in Action: ABPP, CCCP, and Covalent Strategies for Target Deconvolution

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) is a powerful chemoproteomic technology that utilizes small molecule chemical probes to directly interrogate the functional state of enzymes within complex proteomes [16] [24]. Unlike traditional genomic or proteomic methods that measure protein abundance, ABPP directly monitors enzyme activity by employing designed activity-based probes (ABPs) that covalently bind to the active sites of enzymes [25]. This capability makes ABPP particularly valuable for target identification research, as it can reveal changes in enzyme activity that occur without alterations in protein expression levels, providing a functional dimension to proteome analysis [16].

The foundational principle of ABPP lies in its use of covalent binding probes that target mechanistically related classes of enzymes based on their catalytic mechanisms rather than overall sequence or structural similarity [25]. Since its initial development in the late 1990s, with roots tracing back to covalent affinity chromatography experiments from the 1970s, ABPP has evolved into a versatile platform that addresses numerous challenges in drug discovery [16] [24]. These challenges include the development of highly selective small-molecule inhibitors, the discovery of new therapeutic targets, and the illumination of target proteins in native biological systems ranging from cell lysates to intact animals [16].

Fundamental Principles and Probe Design

Core Components of Activity-Based Probes

The effectiveness of ABPP relies on the sophisticated design of activity-based probes, which typically consist of three fundamental components that work in concert to target, react with, and report on enzyme activity.

Reactive Group (Warhead): This is an electrophilic moiety designed to covalently bind to nucleophilic residues in the active sites of target enzymes [16] [26]. The warhead determines the classes of enzymes the probe can target, with common examples including epoxides, Michael acceptors, and sulfonate esters that target serine, cysteine, or threonine proteases [24]. The warhead specifically reacts with the catalytically active form of enzymes, distinguishing active enzymes from their inactive zymogens or inhibitor-bound forms [25].

Linker Region: This component serves as a spacer module that connects the reactive group to the reporter tag [16]. The linker modulates the reactivity and selectivity of the warhead and can be a simple alkyl chain, polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer, or more sophisticated cleavable units that enable additional analytical manipulations [24]. Well-designed linkers enhance target specificity by reducing steric hindrance and non-specific interactions [16].

Reporter Tag: This element provides a detection handle for visualizing, enriching, or quantifying probe-labeled proteins [16]. Common tags include fluorophores (e.g., fluorescein, rhodamine) for gel-based detection and microscopy, or biotin for affinity enrichment and mass spectrometry analysis [26]. To improve cell permeability for in vivo applications, smaller bioorthogonal groups like alkynes or azides are often used in a two-step labeling process involving click chemistry [16].

Distinguishing ABP Types

ABPP methodologies primarily utilize two classes of probes that differ in their targeting mechanisms and applications:

Activity-Based Probes (ABPs): These probes contain reactive warheads that target classes of enzymes sharing common catalytic mechanisms [16]. For example, fluorophosphonate-based probes broadly target serine hydrolases by covalently modifying their active site serine residue [25]. ABPs require mechanistic knowledge of enzyme classes but can profile entire enzyme families without prior knowledge of specific members [16].

Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs): These probes utilize a highly selective recognition motif coupled with a photo-affinity group that labels target proteins upon UV irradiation [16]. AfBPs offer greater specificity for individual proteins but require prior knowledge of target-ligand interactions [16]. They are particularly valuable for studying non-enzymatic protein targets or when no suitable warhead exists for a target of interest.

Table: Key Characteristics of ABPP Probe Types

| Feature | Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Basis | Enzyme catalytic mechanism | Protein-ligand binding interactions |

| Selectivity | Class-wide (enzyme families) | Protein-specific |

| Prior Knowledge Required | Mechanistic understanding of enzyme class | Known ligand-protein interaction |

| Labeling Trigger | Spontaneous covalent reaction | UV irradiation |

| Applications | Profiling enzyme families, activity monitoring | Target validation, ligand engagement studies |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

General ABPP Workflow

The implementation of ABPP follows a systematic workflow that can be adapted for various experimental goals, from target discovery to inhibitor validation. The following diagram illustrates the core ABPP workflow, highlighting key decision points and methodological options.

Sample Preparation and Probe Labeling

The initial steps in any ABPP experiment involve careful sample preparation and optimization of labeling conditions:

Sample Selection: ABPP can be applied to diverse biological systems including cell lysates, live cells, intact tissues, or whole animals [16] [24]. While cell lysates offer experimental control, live cell and in vivo labeling preserve native protein functions, subcellular localization, and protein-protein interactions that may be disrupted in lysates [24].