Chemical Probe Validation for Target Engagement: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of chemical probe validation for target engagement.

Chemical Probe Validation for Target Engagement: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of chemical probe validation for target engagement. High-quality chemical probes are indispensable tools for understanding protein function and validating therapeutic targets, yet their misuse generates erroneous data that undermines research validity. We cover foundational principles defining probe quality, from potency and selectivity criteria to the importance of structural characterization. The article details methodological approaches for confirming cellular target engagement, highlighting techniques like NanoBRET and CETSA that bridge the gap between biochemical and cellular contexts. We address common pitfalls in probe use and present optimization strategies, including the systematic 'Rule of Two' framework. Finally, we explore validation through orthogonal probes and comparative analysis with genetic methods, providing a complete roadmap for employing chemical probes with confidence in basic research and drug discovery.

Defining High-Quality Chemical Probes: The Bedrock of Reliable Research

What is a Chemical Probe? Distinguishing Tools from Drugs and Inhibitors

In the field of chemical biology, a chemical probe is a small molecule used to study and manipulate a biological system by reversibly binding to and altering the function of a specific biological target, most commonly a protein [1]. These well-characterized reagents serve as powerful tools for understanding protein function at a mechanistic level, allowing researchers to ask mechanistic and phenotypic questions about their molecular targets in biochemical, cell-based, or animal studies [2] [3]. Unlike drugs or simple inhibitors, chemical probes are engineered specifically for research applications with an emphasis on selectivity and well-understood behavior, making them indispensable for target validation and functional genomics [4] [3].

The importance of chemical probes has grown significantly with increasing recognition that many published research findings cannot be replicated, partly due to poorly characterized chemical tools [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of chemical probes against related chemical entities, outlines established validation criteria, and presents experimental protocols to ensure proper implementation in target engagement research.

Defining Key Terms: A Comparative Analysis

What Distinguishes a Chemical Probe from Related Concepts?

The term "chemical probe" carries specific connotations that distinguish it from other small molecules used in research. The table below compares key characteristics of chemical probes against related concepts:

| Characteristic | Chemical Probe | Inhibitor/Ligand | Drug |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Research tool for target validation and biological discovery [3] | Modulate target activity, but may lack comprehensive characterization [4] | Therapeutic intervention in patients |

| Selectivity Requirements | High selectivity (>30-fold against related targets) [5] [6] | May have unknown or limited selectivity profile | Polypharmacology may be therapeutically beneficial [3] |

| Characterization Level | Extensively profiled against target families and pharmacologically relevant off-targets [3] | Potency established but may lack comprehensive selectivity data | Optimized for human pharmacokinetics and safety |

| Available Controls | Typically accompanied by matched target-inactive compound [5] [6] | Often used without controlled structural analogs | Clinical formulations may include placebos |

| Optimal Use Concentration | Cellular activity at ≤1 μM [5] [6] | May be used at higher, less specific concentrations | Dosed to achieve therapeutic plasma levels |

Quantitative Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

Major research consortia have established specific criteria to define high-quality chemical probes. The following table summarizes the consensus requirements:

| Parameter | Minimum Standard | Ideal Standard |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Potency | <100 nM (biochemical assay) [5] [6] | <10 nM |

| Selectivity | ≥30-fold over related proteins [5] [6] | ≥100-fold with proteome-wide selectivity assessment |

| Cellular Activity | ≤1 μM for druggable targets [5] [6] | ≤100 nM with demonstrated target engagement |

| Negative Controls | Structurally similar inactive compound (where feasible) [5] [6] | Multiple control compounds with varying inactivity |

| Orthogonal Probes | One additional probe with different chemotype [4] | Multiple orthogonal probes for robust validation |

Experimental Design: Best Practices for Chemical Probe Validation

The "Rule of Two" for Rigorous Research

A systematic review of 662 publications employing chemical probes revealed that only 4% used them within recommended concentration ranges while including both inactive controls and orthogonal probes [4]. This concerning finding led to the proposal of "the rule of two" [4]:

- Employ at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes with different chemotypes, and/or a pair of a chemical probe and matched target-inactive compound)

- Use both probes at their recommended concentrations in every study

This approach helps confirm that observed phenotypes result from on-target effects rather than off-target activities.

Experimental Workflow for Probe Validation

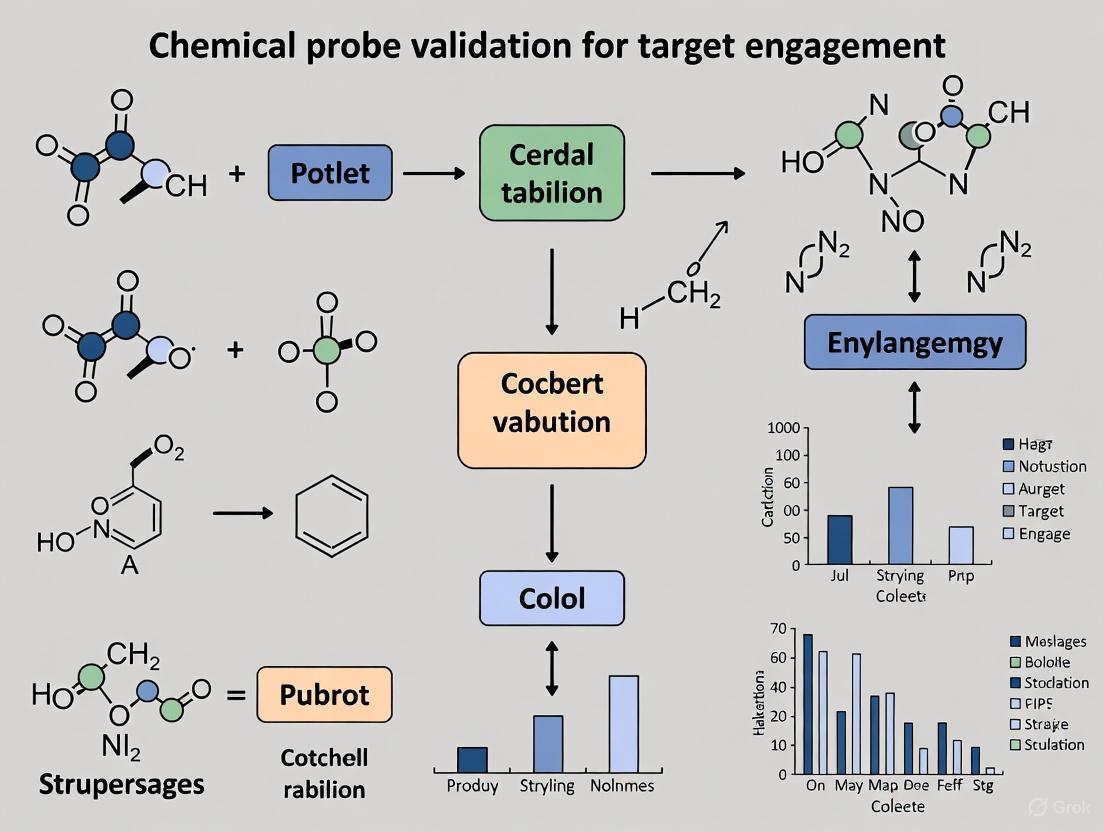

The following diagram illustrates a rigorous experimental workflow for chemical probe validation:

Common Pitfalls in Chemical Probe Implementation

The same systematic review identified several critical shortcomings in current practices [4]:

- Concentration errors: Only 20% of studies used probes within recommended concentration ranges

- Missing controls: Just 24% employed available target-inactive control compounds

- Lack of orthogonal validation: Mere 14% used orthogonal probes with different chemotypes

- Combined deficiencies: Only 4% of publications satisfied all three quality parameters

These implementation failures significantly compromise research validity and contribute to the reproducibility crisis.

Essential Research Reagents for Probe Validation

The table below details key reagents required for rigorous chemical probe experiments:

| Reagent Type | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Chemical Probe | Selective modulation of target protein | UNC1999 (EZH2 inhibitor) [4], (+)-JQ1 (BET bromodomain inhibitor) [3] |

| Matched Inactive Control | Control for off-target effects; structurally similar but target-inactive | Available for probes from SGC-UNC [5], EUbOPEN [6] |

| Orthogonal Chemical Probe | Distinct chemotype targeting same protein; confirms on-target effects | GSK-J4 (KDM6 inhibitor) [4], I-BET (BET inhibitor) [3] |

| Target Engagement Assays | Confirm cellular target binding | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [7], biophysical methods [3] |

| Selectivity Profiling Panels | Assess off-target activity | Industry-standard selectivity panels [3], broad proteomic profiling |

Case Studies: Impact of High-Quality Chemical Probes

Successful Probe Applications in Research

BET Bromodomain Probes: Chemical probes including (+)-JQ1, I-BET, and PFI-1 enabled investigation of BET family functions across oncology, inflammation, virology, and male contraception, leading to multiple clinical development programs [3].

EZH2 Methyltransferase Probes: UNC1999 represents a high-quality chemical probe for EZH2, with comprehensive characterization including selectivity profiling against related histone methyltransferases [4].

Kinase Probes: The SGC-UNC has generated high-quality chemical probes for several "dark kinases" (poorly characterized kinases), including SGC-AAK1-1 for adaptor protein 2-associated kinase and SGC-GAK-1 for cyclin G-associated kinase [5].

Problematic Compounds and Better Alternatives

The following diagram illustrates a decision framework for selecting appropriate chemical tools:

Examples of problematic compounds to avoid include [3]:

- Flavones: Often promiscuous pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS)

- Epigallocatechin-3-gallate: Promiscuous PAINS compound

- Lithium Chloride: Typically used at high (mM) concentrations with multiple off-target effects

- Resveratrol: Associated with assay artifacts

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Innovative Approaches to Probe Discovery

Recent advances combine experimental and computational methods to accelerate probe development:

Integrated Machine Learning and HTS: A 2025 study demonstrated an approach combining quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) with machine learning and pharmacophore modeling to rapidly identify selective inhibitors across multiple aldehyde dehydrogenase isoforms [7].

Open Science Initiatives: Consortia like EUbOPEN and the Structural Genomics Consortium provide peer-reviewed chemical probes with associated negative controls, fulfilling strict criteria for potency, selectivity, and cellular activity [6] [8].

Chemical Handles for Targeted Protein Degradation: Beyond conventional inhibitors, chemical handles for E3 ligases enable PROTAC development, expanding the probe toolbox to include degradation-based approaches [8].

Chemical probes represent indispensable tools for target validation and biological discovery when used appropriately. Their distinction from drugs and simple inhibitors lies in their comprehensive characterization, emphasis on selectivity, and availability of controlled structural analogs. The concerning findings that only 4% of publications use chemical probes correctly highlights the critical need for improved education and implementation of best practices [4].

By adhering to the "rule of two," consulting curated resources like the Chemical Probes Portal, and implementing rigorous validation workflows, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their findings. As chemical biology continues to evolve, next-generation probes and emerging technologies promise to further empower biomedical research and drug discovery efforts.

Chemical probes are highly characterized small molecules that selectively bind to and modulate the function of specific protein targets in biological systems [9] [10]. These reagents are indispensable tools for understanding protein function, deciphering biological mechanisms, and validating targets for drug discovery. The value of chemical probes hinges entirely on their quality, as poorly characterized compounds have generated an abundance of erroneous conclusions in the scientific literature [9] [4]. To address this problem, the scientific community has established minimal criteria or "fitness factors" that define high-quality chemical probes, with potency, selectivity, and cellular activity representing the fundamental triad for probe evaluation [9] [10].

Quantitative Standards for Chemical Probe Assessment

To be considered high-quality, chemical probes must satisfy stringent quantitative benchmarks across multiple dimensions. These criteria ensure that observed phenotypic changes can be confidently attributed to modulation of the intended target rather than off-target effects.

Table 1: Minimum Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

| Fitness Factor | Biochemical Standard | Cellular Standard | Validation Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | IC50 or Kd < 100 nM [9] [10] | EC50 < 1 μM [9] [4] [10] | Dose-response relationship demonstrated |

| Selectivity | >30-fold selectivity within protein target family [9] [4] [10] | Similar selectivity profile in cellular context | Profiling against related targets and common off-targets |

| Cellular Activity | Cellular target engagement demonstrated [10] | Functional modulation at <1 μM [9] | Direct target engagement measurements in live cells |

The selectivity requirement is particularly crucial, as even highly selective compounds will engage off-targets if used at excessive concentrations [4]. This principle explains why best practices mandate using chemical probes at the lowest effective concentrations that demonstrate on-target activity.

Experimental Methodologies for Probe Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is essential to confirm that a chemical probe meets the established criteria. The following methodologies represent best practices for comprehensive probe characterization.

Biochemical Potency and Selectivity Assays

Biochemical assays measure the direct interaction between the compound and its purified protein target. Isothermal titration calorimetry and surface plasmon resonance provide direct binding measurements (Kd), while enzyme activity assays determine functional potency (IC50) [9]. For selectivity assessment, broad profiling panels—such as kinome screens for kinase inhibitors—evaluate activity against related proteins to establish selectivity windows [11]. These assays should include both closely related family members and proteins known to be frequent off-targets for the chemical series.

Cellular Target Engagement and Activity

Demonstrating target engagement in live cells provides critical validation that a compound reaches and binds its intended target in physiologically relevant environments [10]. Cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) and resonance energy transfer techniques (BRET/FRET) enable direct measurement of target engagement in cellular contexts [10]. Functional cellular activity should be demonstrated through pathway modulation assays, such as measuring phosphorylation states for kinases or histone modification levels for epigenetic targets, with dose-response relationships establishing cellular EC50 values [4].

Counterassay Controls

Best practices recommend employing two complementary control strategies: structurally matched inactive analogs and orthogonal probes with distinct chemotypes [9] [4]. Inactive control compounds, which are structurally similar but lack activity against the primary target, help identify off-target effects and assay artifacts [9]. Orthogonal probes with different chemical scaffolds but similar target profiles provide confirmation that observed phenotypes result from on-target engagement rather than scaffold-specific artifacts [4].

Diagram 1: Chemical probes must pass through multiple validation gates to achieve quality status.

The Reality of Chemical Probe Usage in Research

Despite established guidelines, systematic analysis reveals significant gaps between recommended practices and actual implementation in biomedical research. A comprehensive review of 662 publications employing chemical probes in cell-based research found that only 4% used chemical probes within recommended concentration ranges while also including appropriate inactive controls and orthogonal probes [4]. This suboptimal implementation persists despite the availability of expert-curated resources, highlighting the need for improved education and adherence to established standards.

The consequences of using poor-quality chemical tools are profound. Weak and non-selective compounds have generated countless erroneous conclusions in the scientific literature [9] [11]. Many frequently used compounds lack sufficient selectivity, with some inhibiting multiple unintended targets—sometimes more potently than their purported primary targets [9]. These problematic tools continue to be used due to historical precedent and citation momentum rather than objective assessment of their qualities [9] [11].

Successful chemical probe development and implementation requires specialized reagents and resources. The following tools represent essential components for probe validation and application.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Probe Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expert-Curated Portals | Chemical Probes Portal [12] [4], SGC Chemical Probes Collection [9] | Provides expert-reviewed assessments of probe quality with usage guidelines and limitations |

| Data-Driven Platforms | Probe Miner [9] [11] | Offers objective, quantitative assessment of >1.8 million compounds against 2,220 human targets |

| Target Engagement Tools | BRET-based binding assays [10], Cellular thermal shift assays | Enable direct measurement of probe-target interaction in live cells |

| Control Reagents | Matched inactive compounds [9] [4], Orthogonal chemical probes [4] | Distinguish on-target from off-target effects through appropriate control experiments |

Implementation Framework for Optimal Probe Usage

To address the documented gaps in probe implementation, researchers should adopt a systematic approach to probe selection and use. The "rule of two" framework proposes employing at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes and/or a pair of an active probe and matched target-inactive compound) at recommended concentrations in every study [4]. This approach significantly increases confidence that observed phenotypes result from on-target engagement.

For animal studies, additional pharmacokinetic parameters must be considered, including dose, administration route, peak plasma concentration, elimination half-life, and unbound compound concentration in plasma and tissues [9]. These parameters ensure adequate target engagement in vivo and help interpret pharmacodynamic responses.

Diagram 2: A sequential validation workflow ensures confident interpretation of results.

The established fitness factors of potency, selectivity, and cellular activity provide a critical framework for evaluating chemical probe quality. By adhering to these minimum criteria and implementing best practices—including using probes at recommended concentrations, incorporating appropriate controls, and consulting expert-curated resources—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and interpretability of their findings. As the chemical biology community continues to expand the repertoire of high-quality probes and improve implementation standards, these essential tools will increasingly fulfill their potential to accelerate both basic biological discovery and therapeutic development.

In both basic research and drug discovery, the selectivity of a chemical probe or therapeutic compound is a fundamental determinant of its utility and reliability. Selectivity refers to a compound's ability to modulate its primary intended target with minimal interaction with unrelated off-target proteins. A lack of selectivity often manifests as promiscuous activity—where a compound shows activity across a wide range of disparate targets—leading to confounding biological data, misleading therapeutic hypotheses, and ultimately, clinical attrition. This guide objectively compares the experimental methodologies central to profiling compound selectivity, providing a framework for rigorous chemical probe validation within target engagement research.

Defining the Challenge: Promiscuity and Its Mechanisms

Promiscuous bioactive compounds are frequent hitters in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns; they appear active against diverse targets but are often false positives intractable for development into useful probes or drugs [13].

The mechanisms of promiscuity can be broadly categorized:

- Assay Technology Interference: Compounds interfere with the assay readout itself, for example, through light-based interference (auto-fluorescence, quenching) in assays utilizing absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence [13].

- Generalized Nonspecific Interference: Compounds modulate the target through undesirable, nonspecific mechanisms. These include:

Compounds exhibiting these behaviors, often flagged by Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters, can contaminate the literature and waste valuable resources. However, PAINS filters, derived from a specific screening methodology (AlphaScreen), have limitations in generalizability and cannot always discriminate between promiscuous and non-promiscuous compounds that share the same substructure [13]. This underscores the need for experimental validation beyond simple structural alerts.

Comparing Selectivity Profiling Technologies

Moving from in silico predictions to experimental validation is crucial. The following table compares the primary technologies used for selectivity profiling, highlighting their key characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Selectivity Profiling Technologies

| Technology | Key Principle | Typical Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best-Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Profiling Panels [14] | Measures compound affinity against a pre-defined panel of purified recombinant proteins (e.g., kinases). | High | Quantitative affinity measurements (IC50, Kd); Direct comparison across related targets. | Cell-free environment may not reflect cellular physiology; Limited to pre-selected targets. | Early-stage affinity screening against an established target family. |

| Chemical Proteomics [15] [14] | Uses compound-derived probes to enrich and identify direct binding proteins from a native proteome via mass spectrometry. | Medium | Proteome-wide scope; Can identify novel, unanticipated off-targets. | Requires synthesis of a functional probe (can be complex); May miss low-abundance targets. | Unbiased identification of a compound's full interactome. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) & CETSA-MS [16] [17] [14] | Measures ligand-induced changes in protein thermal stability in cells or lysates, detected via immunoassay or mass spectrometry. | Medium (MS), High (Immuno) | Probe-free; Works in a cellular context; CETSA-MS is proteome-wide (>5,000 proteins). | Not all proteins show a thermal shift upon binding; Data interpretation can be complex. | Confirming target engagement and profiling selectivity in a physiologically relevant cellular environment. |

| NanoBRET Target Engagement [14] | Measures probe displacement from a NanoLuc-tagged target protein in live cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). | High | Direct, quantitative measurement of affinity (Kd) and occupancy in live cells; Addition-only workflow. | Requires recombinant expression of tagged proteins; Target coverage depends on available cell lines. | High-throughput, quantitative selectivity profiling against a defined panel of proteins in live cells. |

Performance Insights from Comparative Data

The choice of technology significantly impacts the resulting selectivity profile. A compelling example is the kinase inhibitor Sorafenib. When profiled against a panel of 192 kinases, its selectivity profile differed markedly between biochemical (cell-free) and cellular (NanoBRET) assays. The cellular profiling revealed an improved overall selectivity but also identified two novel off-targets (NTRK2 and RIPK2) that were missed in the biochemical screen [14]. This demonstrates that cellular context, influenced by factors like compound permeability and intracellular ATP concentrations, is critical for an accurate assessment and can uncover biologically relevant off-targets.

Similarly, applying proteome-wide methods like CETSA-MS or chemical proteomics to the FDA-approved HDAC inhibitor Panobinostat identified unexpected off-targets, including phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), which potentially explains some of the drug's clinical side effects [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Below are detailed methodologies for two pivotal, complementary assays used for validating selectivity in a cellular context.

Detailed Protocol: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

CETSA measures target engagement by quantifying ligand-induced protein stabilization against thermal denaturation [16] [14].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Compound Treatment: Treat intact cells or cell lysates with the compound of interest and a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO). Incubate under physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂ for cells) to allow for compound uptake and target engagement [16].

- Heat Challenge: Aliquot the cell suspensions into separate PCR tubes. Subject them to a temperature gradient (e.g., a range from 45°C to 65°C) for a defined period (typically 3-10 minutes) using a thermal cycler.

- Cell Lysis and Protein Solubilization: Lyse the heated cells and solubilize proteins using a detergent-containing buffer.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the lysates at high speed (e.g., 13,000-20,000 x g) to separate the soluble (non-denatured) protein from the insoluble (aggregated) protein.

- Analysis: Analyze the soluble protein fraction from each temperature point.

- CETSA (Immunoassay): Use Western blotting or other immunoassays to quantify the remaining soluble target protein. A rightward shift in the melting curve (Tm) indicates thermal stabilization and confirms target engagement [16].

- CETSA-MS (Proteome-Wide): Use quantitative mass spectrometry (e.g., TMT or label-free) to measure thermal stability shifts for thousands of proteins simultaneously, providing an unbiased selectivity profile [17] [14].

Detailed Protocol: NanoBRET Target Engagement Assay

This live-cell assay quantitatively measures the affinity and occupancy of a compound at its target by competing with a fluorescent tracer ligand [14].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells (e.g., HEK293) transiently or stably expressing the protein of interest fused to NanoLuc luciferase.

- Compound and Tracer Addition: Seed cells in a multi-well plate. Co-incubate cells with a fixed concentration of a cell-permeable, target-specific fluorescent tracer ligand and a titration series of the unlabeled test compound.

- Substrate Addition: Add the cell-permeable NanoLuc substrate to the culture medium.

- BRET Measurement: Measure energy transfer (BRET signal). The NanoLuc enzyme oxidizes its substrate, emitting light at ~450nm. If the tracer is bound to the NanoLuc-tagged protein, BRET occurs, and the tracer emits at its specific wavelength (~600nm). If the test compound displaces the tracer, the BRET signal decreases.

- Data Analysis: Plot the dose-dependent decrease in BRET ratio against the compound concentration. Fit the data to a binding model to calculate the apparent affinity (Kd) and the percentage of target occupancy at a given compound concentration [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Successful selectivity profiling relies on a suite of specialized reagents and platforms.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Platforms for Selectivity Profiling

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PAINS Filters [13] | A set of substructure filters used to flag compounds with a high probability of being pan-assay interference compounds. | Early-stage computational triage of HTS hit lists or compound libraries to flag potentially promiscuous chemotypes. |

| Reactivity Models (Deep Learning) [13] | Computational models predicting small-molecule reactivity with biological nucleophiles (e.g., glutathione), providing mechanistic hypotheses for promiscuity. | Identifying compounds with potential nonspecific covalent reactivity; can be combined with PAINS for improved prediction [13]. |

| CETSA Kits/Platforms [17] | Standardized, scalable kits or services for performing CETSA and CETSA-MS. | Unbiased, proteome-wide selectivity profiling in physiologically relevant cellular systems. |

| NanoBRET TE Assay Kits [14] | Optimized kits containing vectors for NanoLuc-fusion proteins, tracer ligands, and substrate for live-cell target engagement studies. | Quantitative, high-throughput selectivity profiling against a predefined panel of targets in live cells. |

| Kinobeads / KiNativ Platform [15] | Bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum kinase inhibitors (kinobeads) or activity-based probes (KiNativ) for chemoproteomic enrichment of kinases. | Profiling the cellular selectivity of kinase inhibitors against hundreds of endogenous kinases in parallel. |

| Bioorthogonal Probes (e.g., Alkyne-tagged) [15] | Compound analogs containing a small, inert chemical handle (e.g., an alkyne) that can be coupled to a reporter tag (e.g., biotin/fluorophore) after live-cell treatment via "click chemistry." | Enriching and identifying direct cellular protein targets of covalent and non-covalent (when paired with a photoreactive group) compounds. |

Achieving and validating compound selectivity is a multi-faceted challenge that requires an integrated experimental strategy. Relying solely on biochemical assays or structural alerts is insufficient, as the cellular environment profoundly influences compound behavior. Technologies like CETSA and NanoBRET, which provide direct, quantitative measurements of target engagement in a live-cell context, are indispensable for generating physiologically relevant selectivity profiles. By leveraging the methodologies and tools detailed in this guide, researchers can de-risk chemical probes and drug candidates, ensure the integrity of biological data, and make more informed decisions throughout the discovery pipeline.

In the rigorous field of target engagement research, chemical probes have become indispensable tools for understanding protein function and validating therapeutic targets. Defined as well-characterized small molecules with confirmed potency and selectivity for a protein of interest, high-quality chemical probes must satisfy minimal fundamental criteria, or "fitness factors," including potency (IC50 < 100 nM in biochemical assays), selectivity (>30-fold within the target family), and cellular activity (EC50 < 1 μM) [18] [4]. However, even the most selective chemical probe can produce confounding results without proper experimental controls. This is where inactive analogs and structural controls become essential companion tools, providing the critical evidence needed to distinguish true on-target effects from spurious off-target activities [18].

The use of target-inactive control compounds represents a cornerstone of best practices in chemical biology. These structurally matched but target-inactive analogs serve as negative controls to confirm that observed phenotypic effects stem from specific on-target engagement rather than nonspecific compound effects [4]. Despite their established importance, a systematic review of 662 biomedical research publications revealed alarmingly low compliance with this fundamental principle, with only 4% of studies employing chemical probes within recommended concentrations while also incorporating both inactive controls and orthogonal probes [4]. This comparison guide examines the critical role of inactive analogs and structural controls in chemical probe validation, providing experimental frameworks and objective data to enhance research rigor in drug discovery and target validation.

Defining Inactive Analogs and Structural Controls

Inactive analogs, often termed "matched target-inactive control compounds," are carefully designed molecules that share close structural similarity with an active chemical probe but lack meaningful activity against the primary intended target [18] [4]. The term "structural controls" encompasses a broader category that includes both these inactive analogs and orthogonal chemical probes—structurally distinct compounds that target the same protein [4].

The molecular design of inactive analogs typically involves minimal structural modifications that specifically disrupt target binding while maintaining similar physicochemical properties. Common design strategies include:

- Introduction of steric hindrance through strategically placed bulky substituents

- Disruption of key binding interactions through functional group manipulation

- Stereochemical inversion at critical chiral centers essential for target engagement

- Core scaffold modifications that alter molecular geometry without significantly changing overall properties

These structural changes are purposefully conservative to ensure the control compound maintains similar cell permeability, solubility, and general off-target profiles as the active probe, while specifically ablating activity against the primary target [18]. This careful balance allows researchers to attribute phenotypic differences specifically to on-target modulation rather than ancillary compound properties.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Ideal Inactive Analogs

| Property | Active Chemical Probe | Inactive Analog Control | Importance for Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Potency | IC50 < 100 nM | >10-30x reduced potency | Confirms on-target engagement drives phenotype |

| Structural Similarity | Reference structure | Minimal changes (1-2 atoms) | Maintains similar physicochemical properties |

| Selectivity Profile | >30-fold selective against family members | Similar off-target profile | Controls for shared off-target effects |

| Cellular Activity | EC50 < 1 μM | Significantly reduced activity | Validates cellular on-target mechanism |

| Physicochemical Properties | Defined logP, MW, PSA | Similar values (±15%) | Ensures comparable cellular uptake and distribution |

The Validation Crisis: Empirical Evidence for Necessary Controls

The biomedical research community faces a significant validation crisis, with numerous studies demonstrating that improper use of chemical probes has generated erroneous conclusions in the scientific literature [18]. A comprehensive systematic review published in Nature Communications in 2023 quantified this problem by analyzing how 662 primary research articles employed eight different well-characterized chemical probes targeting epigenetic proteins and kinases [4]. The findings revealed a startling gap between recommended best practices and actual implementation across the research community.

Table 2: Compliance Analysis of Chemical Probe Usage in 662 Publications

| Chemical Probe | Primary Target | Publications Analyzed | Used Within Recommended Concentration | Used With Inactive Control | Used With Orthogonal Probe | Full Compliance (All Criteria) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNC1999 | EZH2 | 93 | 20% | 19% | 26% | 1% |

| UNC0638 | G9a/GLP | 78 | 37% | 22% | 9% | 4% |

| GSK-J4 | KDM6 | 92 | 9% | 63% | N/A | 0% |

| A-485 | CREBBP/p300 | 86 | 47% | 16% | 15% | 3% |

| AMG900 | Aurora kinases | 84 | 29% | N/A | 61% | 12% |

| AZD1152 | Aurora kinases | 95 | 29% | N/A | 27% | 5% |

| AZD2014 | mTOR | 84 | 44% | N/A | 27% | 8% |

| THZ1 | CDK7/12/13 | 50 | 48% | 28% | 18% | 2% |

| COMBINED | Multiple | 662 | 31% | 27% | 26% | 4% |

The data reveal several critical patterns. First, compliance with recommended concentration ranges was alarmingly low (31% overall), meaning most studies used chemical probes at concentrations where selectivity is compromised [4]. Second, even when inactive controls were available, they were employed in only 27% of studies. Most strikingly, only 4% of publications fulfilled all three best-practice criteria: using probes within recommended concentrations, including inactive controls, and employing orthogonal probes [4].

These findings substantiate concerns about research reproducibility and highlight the urgent need for wider adoption of proper control strategies. The systematic review authors proposed "the rule of two" as a minimal standard: every study should employ at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes or a pair of an active chemical probe and its matched target-inactive compound) at recommended concentrations [4].

Experimental Framework: Implementing Proper Controls

Protocol for Validating Inactive Analogs in Cellular Assays

Implementing proper controls requires systematic experimental approaches. The following protocol outlines key steps for validating and utilizing inactive analogs in cellular assays:

Step 1: Confirmatory Binding Assays

- Perform biochemical binding assays (e.g., ITC, SPR, or biochemical activity assays) to verify loss of target engagement

- Establish dose-response curves to quantify the potency difference (should be >10-30 fold reduced)

- Confirm absence of binding to primary target across multiple assay formats

Step 2: Cellular Target Engagement Assessment

- Employ cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays

- Measure downstream pharmacodynamic biomarkers specific to target modulation

- Confirm reduced cellular potency compared to active probe

Step 3: Counter-Screening for Maintained Off-Target Activity

- Test both active probe and inactive analog in broad selectivity panels (e.g., kinase profiling, GPCR screening)

- Use resources like Probe Miner for objective assessment of selectivity profiles [11]

- Confirm similar off-target profiles where possible, establishing the control's validity

Step 4: Parallel Cellular Phenotyping

- Treat relevant cell models with active probe and inactive analog across a concentration range (include recommended concentrations)

- Assess phenotypic endpoints (viability, differentiation, migration, etc.)

- Include structurally distinct orthogonal probes targeting the same protein where available

- Attribute effects specifically to on-target modulation only when observed with active probe and orthogonal probes but not with inactive analog

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for validating inactive analogs. This workflow ensures systematic characterization before phenotypic studies.

Case Study: EZH2 Inhibitor Validation with UNC1999 and UNC2400

A representative example of proper control implementation comes from epigenetic probe development. UNC1999, a potent inhibitor of the histone methyltransferases EZH2 and EZH1, was developed alongside UNC2400 as its target-inactive control [4]. The validation approach included:

Molecular Design Strategy:

- UNC2400 maintains core structural similarity to UNC1999

- Specific modification introduced to disrupt key binding interactions with the EZH2/1 SAM cofactor pocket

- Maintained similar physicochemical properties to preserve cellular distribution

Experimental Validation Data:

- Biochemical assays demonstrated >100-fold reduction in EZH2 inhibition for UNC2400

- Cellular target engagement confirmed using H3K27me3 reduction as a pharmacodynamic biomarker

- Broad profiling against other epigenetic targets showed maintained off-target profile

- Parallel phenotyping with orthogonal EZH2 inhibitors (GSK343, EPZ-6438) strengthened conclusions

This comprehensive approach established UNC2400 as a validated negative control, enabling researchers to confidently attribute UNC1999-induced phenotypes to specific EZH2/1 inhibition rather than off-target effects.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Chemical Probe Validation

Implementing robust control strategies requires access to well-characterized research reagents. The following table details key resources available to researchers pursuing target validation studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical Probe Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Features | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Chemical Probes | UNC1999 (EZH2), GSK-J4 (KDM6), A-485 (CREBBP/p300) | Potency <100 nM, >30-fold selectivity, defined cellular activity | Primary target modulation, phenotypic screening, pathway analysis |

| Matched Inactive Controls | UNC2400 (for UNC1999), GSK-J5 (for GSK-J4), A-486 (for A-485) | Structural similarity with abolished target binding, similar physicochemical properties | Negative controls for specificity, off-target effect assessment |

| Orthogonal Chemical Probes | Multiple structural classes for same target (e.g., GSK343 for EZH2) | Distinct chemotypes targeting same protein, different off-target profiles | Confirm on-target effects, rule out probe-specific artifacts |

| Online Assessment Tools | Chemical Probes Portal, Probe Miner, SGC Chemical Probes | Expert-curated recommendations, data-driven scoring, accessibility information | Probe selection, quality assessment, usage guidelines |

| Selectivity Profiling Services | Broad kinase profiling, GPCR screening, epigenetic panels | Multi-target assessment, quantitative comparison, structure-activity relationship analysis | Comprehensive selectivity validation, off-target identification |

These research reagents establish a foundation for rigorous chemical probe applications. Online resources like the Chemical Probes Portal provide expert-curated recommendations for over 400 protein targets, while Probe Miner offers data-driven assessment of >1.8 million compounds, enabling objective evaluation of potential chemical tools [18] [11]. The Structural Genomics Consortium and pharmaceutical company initiatives like the Donated Chemical Probes platform further increase access to high-quality chemical probes and their associated controls [4].

Best Practices and Implementation Guidelines

Effective use of inactive analogs and structural controls requires adherence to established best practices. Based on empirical evidence and community consensus, the following guidelines ensure proper implementation:

Concentration Optimization

- Use chemical probes at or near their established cellular EC50 values

- Avoid concentrations >10x cellular EC50 where off-target effects likely dominate

- Include full dose-response curves rather than single concentrations

- Reference recommended concentrations from Chemical Probes Portal [4]

Control Experiment Design

- Include inactive analogs in parallel with active probes across all experiments

- Utilize orthogonal probes with different chemical structures when available

- Employ multiple control types (inactive analogs, orthogonal probes, genetic controls) for robust conclusions

- Apply "the rule of two" - minimum two chemical probes or probe/inactive control pairs [4]

Data Interpretation Framework

- Attribute effects to on-target activity only when observed with active probe and orthogonal probes

- Interpret phenotypes absent with inactive analogs as likely target-specific

- Investigate discrepancies between inactive analogs and orthogonal probes

- Consider residual effects with inactive analogs as potential off-target activities

Diagram 2: Decision framework for interpreting results with controls. This logic flow distinguishes on-target from off-target effects.

The empirical evidence clearly demonstrates that inactive analogs and structural controls remain underutilized yet essential components of rigorous chemical biology research. With only 4% of published studies fully complying with established best practices, significant opportunity exists to improve research quality and reproducibility [4]. The implementation of "the rule of two"—employing at least two chemical probes or probe/inactive control pairs—represents a achievable minimum standard that would substantially enhance target validation confidence [4].

As chemical probes continue to evolve, with emerging modalities like PROTACs and molecular glues expanding the druggable proteome, the role of proper controls becomes increasingly critical [18]. By adopting systematic approaches to control implementation, leveraging available research reagents, and adhering to community-established best practices, researchers can significantly strengthen experimental conclusions and advance the development of more reliable target validation data. The integration of inactive analogs and structural controls represents not merely a technical refinement but a fundamental requirement for rigorous chemical biology and reproducible drug discovery.

In the field of chemical biology and drug discovery, high-quality chemical probes are indispensable reagents for elucidating protein function and validating therapeutic targets. These small-molecule tools enable researchers to modulate protein activity with temporal precision that often surpasses genetic methods, providing critical insights into biological mechanisms and disease pathology [15] [19]. The growing recognition of their importance has led to the establishment of public resources that curate and evaluate these chemical tools, with the Chemical Probes Portal and the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) Chemical Tools collection emerging as two leading platforms. Both resources address a critical need in biomedical research: the widespread use of poorly characterized compounds that can lead to erroneous conclusions and wasted resources [4] [20]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these resources within the context of chemical probe validation for target engagement research, empowering scientists to navigate these platforms effectively and select appropriate probes for their experimental needs.

The Chemical Probes Portal and SGC Chemical Tools collection represent complementary approaches to supporting chemical biology research. The Portal is an expert review-based public resource that empowers chemical probe assessment, selection, and use, featuring over 700 compounds covering 300 protein targets as of 2022 [12] [20]. Its primary mission is to provide the worldwide research community with free, expert assessments of chemical probes and valuable advice on probe selection and use [12]. The resource is hosted at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and is underpinned by approximately 200 active experts in medicinal chemistry, chemical biology, and drug discovery from around the world [20].

The SGC Chemical Tools collection, developed by the Structural Genomics Consortium and collaborators, focuses on developing chemical probes for previously under-studied proteins, with almost 200 probes developed to date [8]. The SGC distinguishes between chemical probes (cell-active, small-molecule ligands that selectively bind to specific biomolecular targets) and chemical handles (cell-active small-molecule ligands, most commonly for E3 ligases, that enable PROTAC development) [8]. All SGC chemical probes and handles undergo evaluation by internal and external expert committees against defined criteria [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Chemical Probe Resources

| Feature | Chemical Probes Portal | SGC Chemical Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Expert reviews and community-driven evaluations | Development and dissemination of probes for under-studied proteins |

| Number of Probes | >700 compounds [20] | ~200 probes developed [8] |

| Target Coverage | >300 protein targets [20] | Focus on previously under-studied proteins |

| Review Process | 3-member Scientific Expert Review Panel (SERP) [12] | Internal and external expert committee [8] |

| Rating System | 4-star system with minimum 3-star recommendation [12] | Meets defined criteria for probes/handles [8] |

| Special Features | Flags unsuitable compounds, links to canSAR and Probe Miner [20] | Includes covalent probes, chemical handles for PROTAC development [8] |

| User Interaction | Probe submission by any scientist, public reviews [12] | Direct access to SGC-developed probes |

Table 2: Probe Quality Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Application in Probe Validation | Resource Utilization |

|---|---|---|

| Target Engagement | Verifies probe interacts with intended target in living systems [15] | Critical for establishing cellular activity [20] |

| Selectivity Profiling | Evaluates preferential action against intended protein vs. off-targets [20] | Broad profiling within protein family and beyond [21] |

| Potency Assessment | Measures IC50/KD values; typically <100 nM in vitro [4] | Evidence of cellular activity at recommended concentrations [4] |

| Structural Data | PDB IDs for probe-target interactions [21] | Supports mechanism of action understanding |

| Negative Controls | Structurally similar but biologically inactive compounds [19] | Recommended for confirming on-target effects [19] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies for Probe Validation

Assessing Target Engagement in Living Systems

Target engagement—verifying that a chemical probe directly interacts with its intended protein target in a living system—represents a critical validation parameter that should become standard practice in chemical probe and drug discovery programs [15]. Establishing this parameter is essential because different cell types and model organisms may show varied probe uptake and metabolism, as well as distinct target expression levels and distribution [15]. The most straightforward target engagement assays for enzyme-targeting probes involve measurement of substrate and product changes, though this approach can become problematic when measured biomolecules are not uniquely modified by the target enzyme of interest [15].

Established methods for direct measurement of probe-protein interactions include radioligand-displacement assays, which can be adapted to create photoactivatable radioligands to covalently label proteins [15]. Competition with a non-radioactive chemical probe can then occur in living cells, with target engagement measured ex situ by techniques such as SDS-PAGE-radiography [15]. These assays depend on having a selective radioligand for the protein of interest, which may not be available for less well-characterized targets [15].

Emergent chemoproteomic methods have been introduced to measure target engagement more comprehensively in cells. Platforms such as kinobeads and KiNativ enable broad profiling of kinase activities in native proteomes, allowing researchers to verify kinase-inhibitor interactions in cells and detect unanticipated off-targets [15]. For covalent probes, activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) methods can be employed, where covalent ligands are appended to reporter tags such as fluorophores, biotin, and latent affinity handles like alkynes and azides [15]. These can be used in a competitive mode to identify proteins whose ABPP signals are blocked by pre-treatment of cells with an unlabeled chemical probe [15].

Diagram 1: Chemical Probe Validation Workflow showing key experimental stages and methodologies for comprehensive probe characterization.

The "Rule of Two" for Robust Experimental Design

A systematic review of 662 publications employing chemical probes in cell-based research revealed that only 4% of analyzed eligible publications used chemical probes within the recommended concentration range and included inactive compounds as well as orthogonal chemical probes [4]. These findings indicate that best practices with chemical probes are yet to be implemented in biomedical research. To address this, researchers have proposed 'the rule of two': employing at least two chemical probes (either orthogonal target-engaging probes, and/or a pair of a chemical probe and matched target-inactive compound) at recommended concentrations in every study [4].

The rule of two provides a framework for increasing the robustness of conclusions drawn from chemical probe experiments. Even the most selective chemical probe will become non-selective if used at high concentrations, making adherence to recommended concentration ranges essential [4]. Similarly, the inclusion of structurally matched target-inactive control compounds helps distinguish on-target effects from off-target or non-specific activities [19]. When available, employing orthogonal chemical probes with different chemical structures but targeting the same protein provides additional confidence that observed phenotypic effects result from on-target modulation [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Chemical Probe Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Chemical Probes | UNC1999 (EZH2 inhibitor), FM-381 (JAK3 covalent inhibitor) [4] [21] | Selective modulation of specific protein targets in cellular assays |

| Matched Inactive Controls | Structurally similar but biologically inactive analogs [19] | Distinguishing on-target from off-target effects |

| Orthogonal Probes | Chemically distinct compounds targeting same protein [4] | Verifying on-target mechanisms through different chemical scaffolds |

| Target Engagement Tools | Kinobeads, ABPP reagents, CETSA reagents [15] | Confirming direct target engagement in physiological systems |

| Selectivity Panels | Broad kinase profiling, diverse enzyme family panels [19] | Assessing selectivity across related and unrelated protein targets |

Best Practice Guidelines for Probe Selection and Use

Selection Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

The minimal fundamental criteria for chemical probes, known as fitness factors, include potency, selectivity, and cellular activity [4]. In principle, chemical probes should adhere to an in vitro potency of less than 100 nM, selectivity for the targeted protein of at least 30-fold against sequence-related proteins of the same family, and on-target cellular activity at concentrations ideally below 1 μM [4]. For a high-quality probe, researchers should look for compounds that are highly selective for the desired protein target, with broad selectivity profiling within the protein family and beyond, along with evidence of target engagement and activity within cells [20].

The Chemical Probes Portal employs a transparent 4-star rating system, with compounds receiving a minimum of 3 stars specifically recommended for use [12] [20]. The expert reviews provide critical advice on concentrations and assay conditions in cells in vitro, suitability for use in animal models, and any caveats or considerations that may help end users [12]. This expert assessment is complemented by objective, data-driven resources such as Probe Miner, which provides relative ranking of chemical probes based on statistical assessment of large-scale data [4] [20].

Current Challenges and Implementation Gaps

Despite the availability of high-quality chemical probes and clear guidelines for their use, significant challenges remain in their implementation. The systematic review of chemical probe usage revealed concerning patterns: across eight different chemical probes targeting proteins including EZH2, G9a/GLP, KDM6, CREBBP/p300, Aurora, mTOR, and CDK7, only 25% of publications used the probe within the recommended concentration range, only 13% used an available inactive control, and only 4% used both the probe at the recommended concentration and included an inactive control as well as an orthogonal probe [4].

These findings highlight the critical need for improved education and communication about best practices in chemical probe use, particularly among biological researchers who may lack expertise in medicinal chemistry and pharmacology [20]. Journal editors, grant reviewers, and funders can play an important role in promoting better practices by requiring appropriate experimental design and reagent quality in published studies and funded research [20].

Diagram 2: Best Practices Framework illustrating the "Rule of Two" approach for robust experimental design using chemical probes.

The Chemical Probes Portal and SGC Chemical Tools collection represent vital community resources that support rigorous and reproducible chemical biology research. While they employ different models—the Portal providing expert reviews of multiple compounds from various sources, and the SGC focusing on developing and disseminating its own probes for under-studied proteins—both share a common goal: increasing the quality and robustness of biomedical research through better chemical tools [8] [12] [20]. As the field moves toward the Target 2035 goal of providing a high-quality probe for every human protein, these resources will play an increasingly important role in empowering researchers with trusted tools and guidance [22]. By understanding the complementary strengths of each platform and adhering to best practices in chemical probe selection and use—including the "rule of two" and robust target engagement assessment—researchers can significantly enhance the validity and impact of their findings in basic biology and drug discovery.

Bridging the Gap: Methodologies for Confirming Cellular Target Engagement

In the rigorous pathway of drug discovery, target engagement (TE) stands as a critical, non-negotiable pillar in the validation of chemical probes and therapeutic candidates. It serves as the definitive proof that a small molecule interacts with its intended protein target within a biologically relevant context, bridging the gap between in vitro potency and cellular efficacy. Without robust evidence of target engagement, hypotheses about a compound's mechanism of action remain unverified, potentially leading to costly misinterpretations of phenotypic data and failed clinical trials. As drug discovery faces increasing pressure to improve efficiency and success rates, the implementation of reliable, predictive target engagement assays has become more crucial than ever. This guide objectively compares the experimental strategies and technologies that empower researchers to confidently validate this essential parameter.

Comparative Technologies for Measuring Target Engagement

A range of technologies exists to measure drug-target interactions, each with distinct strengths and applications. The following section provides a structured comparison of key methodologies.

Comparison of Key Target Engagement Assays

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of several prominent target engagement assay technologies.

| Assay Technology | Methodology Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Sample Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Protein Stability Assay (CPSA) [23] | Measures target stability shift in cellular lysates using chemical denaturants. | Simple, cost-effective, HTS-compatible, uses cellular lysates [23]. | Requires optimization of denaturant type/concentration [23]. | pXC50, Potency shift relative to control [23]. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [7] | Measures target stability in intact cells or lysates using thermal denaturation. | Applicable in live cells, label-free, can map interactions proteome-wide. | Requires specialized equipment (qPCR), may not detect all binding modes. | Melting temperature (Tm) shift (ΔTm). |

| Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs) [24] | Use non-covalent or photoaffinity-based probes for target capture and detection. | Less impact on protein's natural biological functions, versatile detection [24]. | Requires complex probe design/synthesis, potential for false positives [24]. | Target identification via MS or fluorescence. |

| Activity-Based Probes (AcBPs) [24] | Contain reactive groups that covalently bind active site residues of target proteins. | High selectivity for active enzymes, confirms functional state [24]. | Can obstruct protein's natural function, limited by reactive group choice [24]. | Target identification and activity status. |

| Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) [24] | Proximity-based assay detecting energy transfer between luciferase-tagged protein and fluorescent ligand. | Highly sensitive, suitable for real-time kinetics in live cells. | Requires genetic protein tagging, which may alter native biology. | BRET ratio, equilibrium binding constants (Kd). |

Experimental Protocol: Chemical Protein Stability Assay (CPSA)

The CPSA protocol, as a representative and accessible method, involves the following key steps [23]:

- Lysate Preparation: Generate lysates from cells, preferably those overexpressing the target protein of interest (e.g., with a HiBiT tag for detection).

- Compound Incubation: Expose the lysates to the compounds of interest across a range of concentrations.

- Denaturant Challenge: Treat the lysate-compound mixture with a predetermined concentration and type of chemical denaturant (e.g., Guanidine HCl). The concentration is optimized to achieve a partial denaturation state.

- Detection and Analysis: Quantify the proportion of folded protein using a compatible detection method (e.g., AlphaLISA, Nano-Glo HiBiT Lytic Detection System, or Western Blot). A compound that binds to the target will stabilize it, leading to a higher amount of folded protein post-denaturation compared to a control (e.g., DMSO). This data is used to generate a denaturant response curve and calculate potency values (pXC50).

Diagram 1: CPSA assay workflow for measuring target engagement.

Supporting Experimental Data: CPSA Performance

Data from the literature demonstrates the utility of CPSA. A study performing target engagement for p38 showed a significant correlation between pXC50 values obtained via CPSA and those from a commercial thermal denaturation assay, validating the method's reliability [23].

Furthermore, CPSA has been successfully applied to diverse targets like BTK and KRAS, demonstrating its broad applicability. In a key experiment, the assay differentiated the engagement profile of two KRAS inhibitors: Adagrasib (which is specific for the G12C mutation) and BI-2856 (a pan-RAS inhibitor). CPSA correctly showed engagement of Adagrasib only with the KRAS G12C mutant lysate and not the wild-type, highlighting its specificity in characterizing compound binding [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful target engagement studies rely on a suite of critical reagents and tools.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Target Engagement | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| HiBiT-Tagged Proteins [23] | A small peptide tag (11 amino acids) that provides a highly sensitive, luminescent method for detecting and quantifying proteins in lysates or live cells. | Detection of target protein stability in CPSA using the Nano-Glo HiBiT Lytic Detection System [23]. |

| Chemical Denaturants [23] | Agents like Guanidine HCl that unfold proteins. The concentration required to denature a target is shifted by ligand binding. | The unfolding agent in CPSA to challenge protein stability after compound incubation [23]. |

| Affinity-Based Probes (AfBPs) [24] | Bifunctional molecules with a target-binding moiety, a linker, and a tag (e.g., biotin, fluorophore) for pull-down or detection. | Target identification and validation in chemical proteomics studies; often incorporate photoaffinity groups for covalent capture [24]. |

| Tool Compounds [25] | Selective, well-characterized small-molecule modulators of a protein's activity. | Used as positive controls in assay development and for preclinical target validation to benchmark new chemical probes [25]. |

| AlphaLISA Detection Beads [23] | Bead-based proximity assay that generates a signal when donor and acceptor beads are brought in close proximity by a biomolecular interaction. | An alternative method to detect the folded/denatured protein ratio in CPSA experiments [23]. |

In conclusion, demonstrating direct target engagement is not merely a box-ticking exercise but a non-negotiable step in the rational validation of chemical probes and drug candidates. Technologies like CPSA, CETSA, and affinity-based probes provide robust, often complementary, paths to obtaining this critical evidence. By integrating these assays early in the screening cascade—using well-defined tool compounds and reagents—researchers can prioritize high-quality hits, de-risk the development pipeline, and build a solid foundational understanding of compound mechanism of action. As the field evolves, the continued refinement and application of these target engagement strategies will be paramount in translating chemical probes into successful therapeutics.

NanoBRET (Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer) is a live-cell binding assay technology that uses bioluminescence resonance energy transfer to quantitatively measure drug-target interactions in a physiologically relevant cellular context [26]. This technology represents a significant advancement in the field of chemical probe validation, enabling researchers to measure target occupancy, compound affinity, residence time, and permeability directly in living cells [26]. Unlike traditional biochemical assays that occur in isolated systems, NanoBRET provides a bridge between in vitro binding data and cellular activity by reporting on specific compound binding within the complex environment of a live cell [27].

The core innovation of NanoBRET technology lies in its pairing of an optimized luciferase donor with appropriate acceptor fluorophores. The technology utilizes NanoLuc luciferase (Nluc), a small (19 kDa) enzyme engineered from the deep-sea shrimp Oplophorus gracilirostris, which generates approximately 150 times stronger luminescence intensity than traditional Firefly (Fluc) or Renilla luciferases (Rluc) used in earlier BRET systems [28] [29]. This enhanced brightness, combined with Nluc's physical stability and appropriate folding in various cellular environments, enables new BRET applications that were not feasible with previous BRET1 or BRET2 methodologies [28].

Technological Foundations and Advantages

Core Mechanism of NanoBRET

The fundamental principle of NanoBRET relies on non-radiative energy transfer between a luciferase donor and a fluorophore acceptor when they are in close proximity (typically 1-10 nm) [28] [29]. For NanoBRET target engagement assays, the target protein is expressed as a fusion with NanoLuc luciferase, while a cell-permeable fluorescent tracer is designed to bind reversibly to the target protein [26]. When the tracer binds to the target-NanoLuc fusion protein in live cells, the proximity allows resonance energy transfer from NanoLuc to the tracer, resulting in a detectable BRET signal [26]. Test compounds that compete for the binding site displace the tracer, leading to a reduction in BRET signal that can be quantified to determine binding affinity and occupancy [26].

The energy transfer efficiency depends on two critical factors: sufficient spectral overlap between the donor emission and acceptor excitation spectra, and close physical proximity between the donor and acceptor molecules [28]. The introduction of NanoLuc was transformative for BRET applications because its emission peak at approximately 460 nm is slightly blue-shifted compared to Rluc and about 20% narrower, facilitating better spectral separation when paired with red-shifted acceptors [28]. The standard NanoBRET configuration uses the NanoBRET 618 fluorophore (with emission around 618 nm), creating a spectral separation of approximately 170 nm from the NanoLuc donor, which significantly reduces background noise and improves assay sensitivity [28].

Advantages Over Traditional BRET Systems

NanoBRET offers several distinct advantages that make it particularly valuable for modern drug discovery and chemical probe validation:

Enhanced Sensitivity and Dynamic Range: The dramatically brighter signal from NanoLuc (approximately 150-fold greater than traditional luciferases) increases NanoBRET assay sensitivity typically by more than one order of magnitude [28]. This enhanced signal strength enables applications with weak promoters or in cells that are difficult to transfect [28].

Improved Spectral Separation: The combination of NanoLuc's blue-shifted, narrower emission spectrum with red-shifted acceptor fluorophores provides superior spectral separation compared to earlier BRET systems [28] [29]. This significantly reduces background signal and improves the signal-to-noise ratio, which is critical for accurate binding measurements [28].

Reduced Steric Hindrance: The small size of NanoLuc (19 kDa) is less likely to interfere with the normal function, configuration, or cellular localization of target proteins compared to the larger Rluc (36 kDa) used in traditional BRET systems [28]. This is particularly important for studying structurally sensitive targets like GPCRs and kinases.

Flexibility in Acceptor Options: NanoBRET is compatible with various acceptor fluorophores including HaloTag fusion proteins, fluorescent chemical tracers, and dyes like TAMRA, BODIPY, and Alexa Fluor derivatives [28] [30]. This flexibility allows researchers to tailor the system to their specific experimental needs.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism and key advantages of the NanoBRET technology:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Comparison with Alternative Technologies

NanoBRET technology occupies a unique position in the landscape of binding assay methodologies, offering distinct advantages and limitations compared to alternative approaches. The following table provides a systematic comparison of NanoBRET with other established technologies:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Binding Assay Technologies

| Technology | Cellular Context | Measurement Type | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NanoBRET [26] [27] | Live cells | Direct binding (Affinity, occupancy, residence time) | Quantitative live-cell kinetics; measures intracellular availability; suitable for high-throughput screening | Requires protein tagging; potential tag-induced artifacts |

| TR-FRET [30] | Biochemical (cell-free) | Direct binding | Excellent signal-to-noise; time-resolved detection; well-established | Lacks cellular context; membrane impermeability concerns |

| NanoBiT [31] | Live cells | Protein-protein interaction (requires complementation) | Standard luminescence detection; no specialized filters needed; measures direct interaction | Signal sensitive to cell number; requires physical subunit interaction |

| Radioligand Binding [32] | Membrane preparations or fixed cells | Direct binding | High sensitivity; well-validated; no protein engineering required | Radioactive hazards; non-physiological conditions; no real-time kinetics |

| SPR | Cell-free | Direct binding | Label-free; kinetic parameters; high information content | Technical complexity; artificial membrane systems; equipment cost |

The comparative performance of these technologies reveals that NanoBRET provides an optimal balance between physiological relevance and experimental tractability for target engagement studies. Unlike TR-FRET, which is typically conducted in biochemical formats, NanoBRET enables researchers to study binding events in live cells, accounting for critical cellular factors such as membrane permeability, intracellular compound processing, and the presence of endogenous binding partners [30] [27]. Compared to radioligand binding assays, NanoBRET offers similar sensitivity without the safety concerns and regulatory challenges associated with radioactive materials, while additionally enabling real-time kinetic measurements in physiologically intact systems [32].

Advantages Over Traditional BRET Systems

When specifically compared to earlier BRET generations, NanoBRET demonstrates marked improvements in key performance parameters:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of BRET Systems

| Parameter | BRET1 | BRET2 | NanoBRET |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor Luciferase | Renilla (36 kDa) | Renilla (36 kDa) | NanoLuc (19 kDa) |

| Donor Emission Peak | 475 nm | 395 nm | 460 nm |

| Typical Acceptor | YFP | GFP2/GFP10 | NanoBRET 618 |

| Acceptor Emission | 515-560 nm | 500-540 nm | 550-675 nm |

| Signal Strength | Moderate | Low (poor quantum yield) | High (~150x BRET1) |

| Spectral Separation | Limited (high background) | Improved (large Stokes shift) | Excellent (~170 nm separation) |

| Dynamic Range | Moderate | Limited | Linear over several orders of magnitude |

| Steric Interference | Significant (large donor) | Significant (large donor) | Minimal (small donor) |

The progression from BRET1 through BRET2 to NanoBRET represents a consistent trajectory of improvement in signal strength, spectral separation, and overall experimental flexibility [28]. BRET1, which utilizes Rluc as the energy donor and YFP as the acceptor, suffers from high background noise due to spectral proximity between donor and acceptor emissions [28]. BRET2 was developed to address this limitation by using the DeepBlueC substrate to shift the Rluc emission to approximately 395 nm and GFP2 or GFP10 as acceptors, creating greater spectral separation but at the cost of substantially lower emission intensities and poor luminescence stability [28]. NanoBRET represents the culmination of these technological developments, combining the strong, stable signal of NanoLuc with optimal acceptor fluorophores to achieve both high signal strength and excellent spectral resolution [28] [29].

Experimental Implementation

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NanoBRET assays requires several key reagents and materials that form the foundation of the experimental system:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NanoBRET Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| NanoLuc-Tagged Target | Energy donor fused to protein of interest | Custom cloning; pre-validated constructs |

| Cell-Permeable Tracer | Fluorescent acceptor that binds target | NanoBRET 618; BODIPY conjugates; TAMRA-labeled ligands |

| Furimazine Substrate | NanoLuc enzyme substrate | Nano-Glo Substrate |

| Microplate Reader | Detection instrument with temperature control | BMG LABTECH CLARIOstar Plus; PHERAstar FSX |

| Appropriate Filters | Spectral separation of donor/acceptor signals | 460 nm BP filter (donor); 610 nm LP filter (acceptor) |

| Cell Culture Components | Maintenance of live cells during assay | Appropriate media; multi-well plates; incubation systems |

The selection of an appropriate fluorescent tracer is particularly critical for assay performance. Recent research has demonstrated that some tracers originally developed for TR-FRET applications, such as T2-BODIPY-FL, can also function effectively in NanoBRET systems, providing greater experimental flexibility [30]. In cross-platform evaluation studies, T2-BODIPY-589 demonstrated superior performance in NanoBRET (Z' factor up to 0.80) while maintaining acceptable functionality in TR-FRET (Z' = 0.53), suggesting that thoughtfully designed tracers can bridge biochemical and cellular assay formats [30].

Standard Experimental Protocol

A typical NanoBRET target engagement assay follows a standardized workflow that can be adapted for specific experimental needs:

Step 1: Construct Preparation

- Generate a fusion construct of your target protein with NanoLuc luciferase using Flexi Vector System-compatible vectors or vectors with multiple cloning sites [26]. The NanoLuc tag can be positioned at either the N- or C-terminus, but placement should be optimized to minimize disruption of protein function and cellular localization.

Step 2: Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Culture appropriate cells (typically HEK293 or other readily transfectable cell lines) under standard conditions.

- Transfect cells with the NanoLuc-tagged target construct using preferred transfection method. Optimization of transfection conditions may be necessary to achieve appropriate expression levels without cellular toxicity.

Step 3: Tracer Titration and Validation

- Perform saturation binding experiments with the fluorescent tracer to determine its dissociation constant (Kd) in the cellular context [26]. This critical step ensures that subsequent competition assays are conducted under quantitative conditions.

- Establish the optimal tracer concentration for competition assays, which should be less than or equal to the tracer Kd value [26].

Step 4: Assay Execution

- Plate transfected cells in appropriate multi-well plates and allow to adhere and recover.

- Add test compounds at desired concentrations along with the predetermined optimal concentration of fluorescent tracer.

- Add furimazine substrate to initiate the bioluminescence reaction. For the Intracellular TE format, use the Nano-Glo Substrate/Inhibitor solution to ensure that the BRET signal measured results from intracellular interactions [26].

Step 5: Signal Detection and Data Analysis

- Measure donor and acceptor signals using a compatible microplate reader with appropriate filter sets [28]. The donor signal (NanoLuc emission) is typically collected using a 460 nm bandpass filter, while the acceptor signal (tracer emission) is collected using a 610 nm longpass filter [31].

- Calculate the BRET ratio as the emission intensity at the acceptor wavelength divided by the emission intensity at the donor wavelength [28].

- For competition assays, plot the BRET ratio against compound concentration to generate displacement curves and calculate apparent Kd values [26].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the NanoBRET target engagement assay workflow:

Applications in Chemical Probe Validation and Drug Discovery

Comprehensive Target Engagement Characterization

NanoBRET technology enables multi-parametric characterization of compound-target interactions that is essential for rigorous chemical probe validation:

Affinity and Occupancy Measurements: NanoBRET TE assays provide quantitative measurements of intracellular compound affinity (apparent Ki) and fractional target occupancy under physiological conditions [26]. The quantitative nature of these measurements enables direct comparison of compound affinity across related targets, supporting selectivity profiling and structure-activity relationship (SAR) optimization [26].