Chemical Probe Target Validation: Best Practices for Reliable Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the rigorous validation of chemical probes, essential tools for target identification and phenotypic screening in biomedical research.

Chemical Probe Target Validation: Best Practices for Reliable Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the rigorous validation of chemical probes, essential tools for target identification and phenotypic screening in biomedical research. It covers foundational principles, from defining the core characteristics of high-quality probes to detailing advanced methodological applications in complex disease models. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies to avoid common pitfalls and outlines a gold-standard, multi-faceted validation framework that integrates chemical, genetic, and proteomic approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource is designed to enhance experimental reproducibility and accelerate the translation of basic research into viable therapeutic candidates.

What is a Chemical Probe? Defining the Gold Standard for Target Validation

In the landscape of drug discovery and biomedical research, the distinction between chemical probes and drugs is fundamental. Chemical probes are highly characterized, cell-active small molecules designed to selectively modulate a specific protein's function, serving as essential tools for understanding underlying biology and validating therapeutic targets [1] [2]. In contrast, drugs are optimized compounds that meet rigorous safety and efficacy standards for human use, with the primary goal of treating, curing, or preventing disease [1]. This technical resource center outlines best practices for employing chemical probes in target validation, providing troubleshooting guidance to ensure robust and reproducible experimental outcomes.

Core Concepts: Chemical Probes Versus Drugs

Definition and Purpose

Chemical Probes are small molecules engineered to potently and selectively bind to specific biomolecular targets, enabling researchers to interrogate biological mechanisms and establish the therapeutic potential of a target [1] [2]. Their primary purpose is to answer mechanistic questions about protein function in a cellular context.

Drugs are small molecules optimized for safe and effective use in humans, meeting stringent regulatory requirements for physicochemical properties, bioavailability, and therapeutic efficacy [1]. Their purpose is clinical application.

Comparative Criteria

Table: Key Distinguishing Criteria for Chemical Probes vs. Drugs

| Criterion | Chemical Probes | Drug Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Investigate biology, validate drug targets [1] | Treat, cure, or prevent disease in humans [1] |

| Mechanism of Action | Must be clearly defined [1] | May not be fully defined [1] |

| Selectivity | High selectivity for intended target is critical (e.g., ≥30-fold over related proteins) [3] | Some off-target effects may be tolerable if clinical safety is maintained [1] |

| Potency | Typically <100 nM in in vitro assays [3] | Optimized for therapeutic dosing |

| Cell Activity & Target Engagement | Required; evidence at <1 μM (or <10 μM for challenging targets) [3] | Required, but assessed in complex in vivo systems |

| Physicochemical & Pharmaceutical Properties | Not required to have full "drug-like" properties (e.g., oral bioavailability) [1] | Must meet high standards for properties like solubility, stability, and molecular weight [1] |

| Negative Control | Should have a structurally similar, inactive compound available [1] [3] | Not required |

| Availability | Freely available for research; data is open [1] [3] | Often restricted due to intellectual property and regulatory constraints [1] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Resources for Chemical Probe Identification and Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Chemical Probe | Selectively modulates a specific protein's function in cells to establish a phenotypic link to a disease [1] [3] | Potent (<100 nM), selective (≥30-fold), cell-active, and accompanied by a negative control [3]. |

| Inactive Negative Control | Distinguishes target-specific effects from non-specific or off-target effects in experiments [1] | Structurally very similar to the active probe but lacks activity on the primary target [3]. |

| Chemogenomic (CG) Library | A collection of well-annotated compounds with overlapping target profiles used for target deconvolution and pathway analysis [3] | Covers a broad target space (e.g., 1/3 of the druggable proteome); useful when highly selective probes are unavailable [3]. |

| Peer-Reviewed Portal (e.g., Chemical Probes Portal) | Online resource to find expert-reviewed recommendations and ratings for chemical probes [4] | Provides community-vetted information on probe quality, selectivity, and best-use practices to guide selection [4]. |

| Donated Chemical Probes (DCP) | A project providing access to peer-reviewed chemical probes donated by academics and industry [3] | Ensures free, unrestricted access to high-quality tools, accelerating target validation [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I select a high-quality chemical probe for my target of interest?

Answer: Follow a multi-step verification process:

- Consult Expert Resources: Begin with the Chemical Probes Portal, a free online resource featuring over 1,100 probes and more than 1,600 expert reviews. This should be your first stop to find peer-reviewed recommendations [4].

- Verify Key Criteria: Ensure the probe meets the minimum community standards:

- Potency: IC50 or EC50 typically < 100 nM in in vitro assays [3].

- Selectivity: At least 30-fold selectivity over related targets, validated in selectivity panels or broad proteomic profiling [3].

- Cell Activity: Demonstrated target engagement in cells at a concentration of ≤1 μM (or up to 10 μM for difficult targets like protein-protein interactions) [3].

- Check for a Negative Control: Always confirm that a structurally related but inactive control compound is available. Using this control is essential for interpreting your results correctly [1] [3].

FAQ 2: I am observing a phenotypic effect with a chemical probe, but also with its supposed "inactive control." What could be the cause?

Answer: This is a critical red flag suggesting your observed phenotype may not be due to on-target inhibition. The most common causes and solutions are:

- Cause 1: Poor Probe Quality. The "inactive control" may not be truly inactive, or the probe itself may have significant off-target activity.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the probe's validation data. Look for results from broad phenotypic or proteomic profiling studies that demonstrate its selectivity. Consider using an alternative probe with a different chemical structure [5].

- Cause 2: Compound Misuse. The compounds are being used at excessively high concentrations, leading to non-specific effects or cytotoxicity.

- Cause 3: Inappropriate Model System. The biological system may have compensating pathways or the target protein may have a function not accounted for.

- Solution: Corroborate your findings using an orthogonal tool, such as CRISPR-based gene knockdown, to see if it replicates the probe's phenotype [1].

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for validating that a chemical probe is engaging its intended target in my cellular model?

Answer: Employ a combination of pharmacological and experimental techniques:

- Dose-Response: Show that the phenotypic effect is concentration-dependent and aligns with the probe's known in vitro potency [3].

- Use of a Negative Control: As highlighted above, the inactive control should not produce the same phenotype as the active probe when used at the same concentration [1].

- Use of a Positive Control: If available, use a well-characterized positive control (e.g., a different probe for the same target or a genetic rescue experiment) to confirm the phenotype is specific.

- Orthogonal Validation: Use a completely independent method, such as CRISPRi or RNAi, to inhibit the same target. If both the genetic inhibition and the chemical probe produce a similar phenotype, confidence in the target-phenotype link increases substantially [1].

- Direct Target Engagement Assays: Implement cellular assays that directly measure the probe's interaction with its target, such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or biophysical methods that detect binding in a cellular lysate or intact cells [5].

FAQ 4: When should I consider using a chemogenomic (CG) library instead of a single chemical probe?

Answer: A CG compound library is an excellent tool for specific scenarios:

- For Target Deconvolution: When you have a phenotypic screen hit from a large library and need to identify which specific target(s) are responsible for the observed effect. By profiling the hit against a panel of compounds with known but overlapping target profiles, you can deduce the causative target [3].

- When a High-Quality Probe is Unavailable: For many understudied proteins, a selective chemical probe may not yet exist. In this case, using a set of CG compounds that hit your target (along with others) can provide initial, albeit more preliminary, insights into the target's biology [3].

- To Explore Signaling Pathways: Using multiple compounds that target different nodes within the same pathway can help you map out functional relationships and identify critical, "druggable" components.

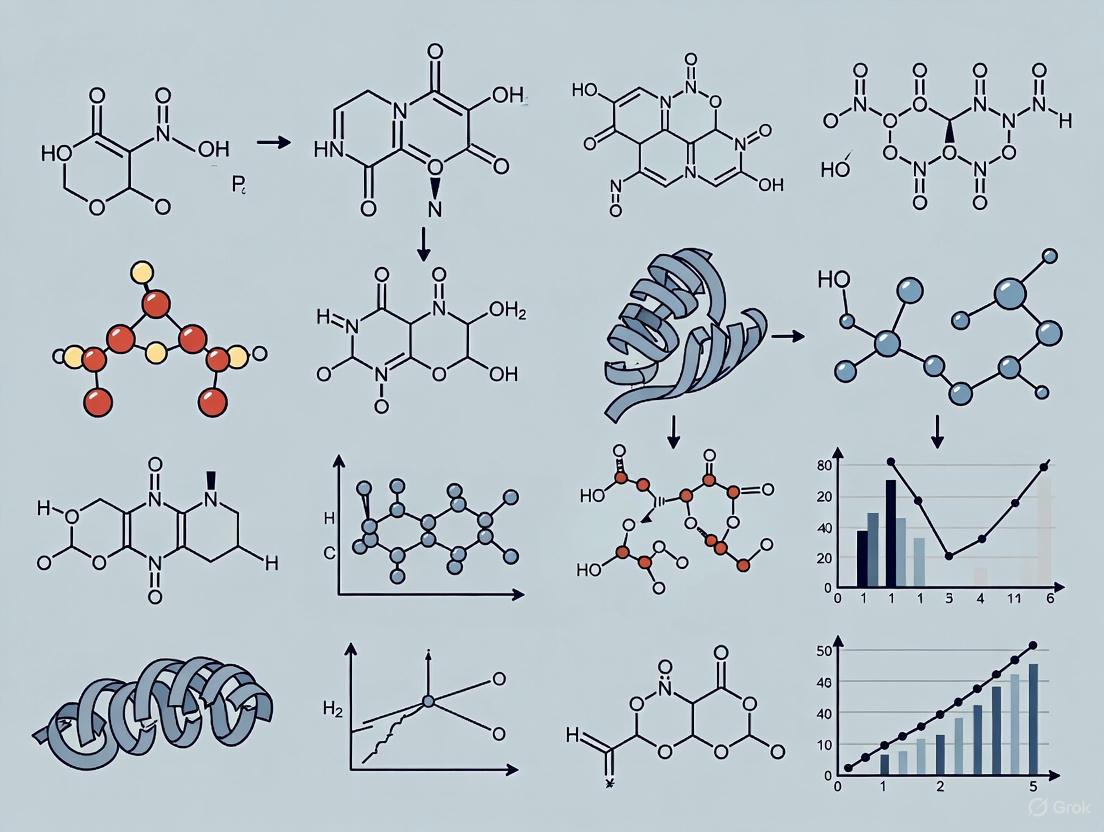

Diagram: A workflow for the rigorous use of chemical probes in target validation experiments, incorporating key troubleshooting checkpoints.

The disciplined application of high-quality chemical probes is a cornerstone of successful target validation and translational research. By adhering to the best practices and troubleshooting guides outlined—rigorous probe selection, mandatory use of controls, dose-response characterization, and orthogonal validation—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and impact of their work. These practices ensure that the foundational biology understood through probes can be confidently translated into the development of safe and effective therapeutics.

Troubleshooting Common Probe-Related Experimental Issues

FAQ: My chemical probe is not producing the expected cellular phenotype. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue often stemming from three main areas: probe concentration, cellular context, or probe quality.

- Problem: The most frequent error is using the probe outside its recommended concentration range. Even highly selective probes become non-selective at high concentrations [6].

- Solution: Adhere to the recommended concentration for cellular assays, which is typically below 1 µM for on-target activity [6] [7]. Always perform a dose-response curve to confirm the effective concentration in your specific cellular model.

- Problem: The probe's cellular activity is dependent on cell permeability and stability. If the probe cannot reach its intracellular target, no phenotype will be observed.

- Solution: Review literature on the probe's cellular pharmacokinetics. Use a positive control cell line with known sensitivity to the probe to validate your experimental system. Consider using a structurally distinct orthogonal probe to confirm the phenotype is target-specific [6].

- Problem: The probe might be outdated, superseded by a better tool, or not a high-quality chemical probe by current standards.

- Solution: Consult the Chemical Probes Portal (www.chemicalprobes.org) to check the expert rating of your probe. Avoid "Historical Compounds" flagged as unsuitable [6] [4].

FAQ: How can I be confident that the observed effect is due to on-target engagement and not an off-target artifact?

Robust target validation requires controlling for off-target effects through careful experimental design.

- Solution: Employ "The Rule of Two". Best practice dictates using at least two chemical probes in every study [6]. This can be achieved by:

- Using a pair of a chemical probe and a matched target-inactive control compound. This control compound should be structurally similar but pharmacologically inactive against the primary target. Any phenotype observed with the active probe but not the inactive control is more likely to be on-target [6] [7].

- Using two orthogonal chemical probes with different chemical structures that engage the same target. If both probes produce the same phenotypic outcome, confidence in the result increases significantly [6].

- Solution: Perform Target Engagement Assays. Use cellular assays that directly measure the probe's interaction with its intended target. For example, if the probe targets a kinase, use a cellular phosphorylation assay of a known substrate to confirm on-target activity.

FAQ: I am developing a new probe. What are the minimal criteria for potency and selectivity?

The chemical biology community has established consensus "fitness factors" for a high-quality chemical probe [7].

- Potency: The probe should have high affinity for its primary target, with an IC₅₀ or Kd < 100 nM in biochemical assays. In cellular assays, it should show on-target activity at an EC₅₀ < 1 µM [7].

- Selectivity: The probe should be selective for its target over other proteins, especially those within the same family. A generally accepted rule is a selectivity of >30-fold against related proteins [6] [7]. This requires broad profiling against panels of related targets (e.g., kinome-wide screens for a kinase inhibitor) to identify and quantify off-target interactions.

Essential Experimental Protocols for Probe Validation

Protocol: Validating Cellular Target Engagement and Permeability

Objective: To confirm that a chemical probe engages its intracellular target at the intended site of action.

Workflow:

- Dose-Response Analysis: Treat cells with a range of probe concentrations (e.g., 1 nM to 10 µM) for a predetermined time.

- Cell Lysis and Analysis: Lyse cells and analyze the direct downstream effects of target engagement.

- For an enzyme inhibitor: Measure substrate levels (e.g., phosphorylation status for a kinase inhibitor, histone methylation for an EZH2 inhibitor) via Western blot or ELISA.

- For a PROTAC: Measure target protein degradation via Western blot.

- Viability Assay: In parallel, run a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo) to distinguish cytotoxic from on-target effects.

- Data Interpretation: The concentration at which the pharmacological effect (step 2) occurs should be lower than the concentration causing non-specific cytotoxicity (step 3). The EC₅₀ for the on-target effect should ideally be below 1 µM [7].

Protocol: Implementing the "Rule of Two" for Robust Phenotypic Confirmation

Objective: To use multiple pharmacological tools to ensure that an observed cellular phenotype is due to on-target modulation.

Workflow:

- Select Probes: Choose a high-quality primary chemical probe, a matched inactive control (where available), and/or an orthogonal chemical probe with a different chemical structure [6].

- Treat Cells: Apply the primary probe, control compound, and orthogonal probe to cells in parallel experiments. Use a minimum of two concentrations within the recommended range for each.

- Measure Phenotype: Quantify the relevant phenotypic readout (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, reporter activity).

- Analyze Data: A high-confidence on-target phenotype is one that is:

- Produced by the primary probe and the orthogonal probe.

- Not produced by the matched inactive control compound.

- Dose-dependent for both active probes.

Compliance with Best Practices in Biomedical Research

An analysis of 662 primary research articles revealed significant room for improvement in the application of chemical probes. The table below summarizes the findings for selected probes [6].

Table 1: Analysis of Chemical Probe Usage in Published Literature

| Probe Target | Protein Family | % of Publications Using Probe within Recommended Concentration | % of Publications Using Matched Inactive Control | % of Publications Using Orthogonal Probes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 | Histone Methyltransferase | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| G9a/GLP | Histone Methyltransferase | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| mTOR | Kinase | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| CDK7 | Kinase | Data from source | Data from source | Data from source |

| Aggregate Analysis | Multiple | ~25% | ~4% | ~4% |

Note: The data is adapted from a systematic review of 662 publications. The aggregate analysis shows that only about 4% of studies complied with all best practices, including using the correct concentration, a negative control, and an orthogonal probe [6].

Minimal Criteria for a High-Quality Chemical Probe

The following table outlines the consensus fitness factors that define a high-quality chemical probe [7].

Table 2: Minimal Criteria for a High-Quality Chemical Probe

| Pillar | Biochemical Criteria | Cellular & In Vivo Application | Key Resources for Verification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | IC₅₀ or Kd < 100 nM | Cellular EC₅₀ < 1 µM | Published dose-response data; Probe Miner database |

| Selectivity | >30-fold selectivity against related targets; extensive off-target profiling | Phenotype replicated by orthogonal probe | Chemical Probes Portal rating; Published selectivity panels |

| Cell Permeability / Stability | Evidence of cellular target engagement | Favorable pharmacokinetics for in vivo use (e.g., plasma concentration, half-life) | Literature on cellular efficacy; in vivo PK/PD studies |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Identifying and Validating Chemical Probes

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal | Expert-Curated Portal | Provides star-rated reviews and recommendations for probes from a scientific expert panel. | www.chemicalprobes.org [4] |

| Probe Miner | Data-Mining Platform | Offers an objective, statistical ranking of chemical probes based on large-scale bioactivity data mining. | https://probeminer.icr.ac.uk/ [6] [7] |

| SGC Chemical Probes | Probe Collection | Provides access to high-quality, unencumbered chemical probes, often with detailed characterization data. | https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes [7] |

| Matched Inactive Control | Critical Reagent | A structurally similar compound with no activity against the primary target, used as a negative control to confirm on-target effects. | (Check vendor catalogs or primary publications for specific probes) [6] |

In the realm of biomedical research and drug development, chemical probes have emerged as indispensable tools for understanding protein function and validating therapeutic targets. These well-characterized small molecules, distinguished from simple inhibitors or early-stage drug candidates by their validated potency and selectivity, enable researchers to interrogate biological systems with precision [6]. However, the power of these tools is entirely dependent on their correct application in experimental settings.

Recent evidence reveals a concerning gap between recommended best practices and actual implementation. A systematic review of 662 publications employing chemical probes in cell-based research found that only 4% of studies adhered to the key recommendations of using probes within their recommended concentration range while also including both inactive control compounds and orthogonal chemical probes [6]. This widespread suboptimal use of chemical probes threatens the validity of countless research findings and highlights the critical need for improved experimental design.

At the heart of robust chemical probe experimentation lies the strategic implementation of negative controls, particularly target-inactive analogs. These controls serve the same fundamental purpose in biomedical research that they do in laboratory experiments: to rule out non-causal interpretations of results by detecting both suspected and unsuspected sources of spurious inference [8]. This technical guide explores the pivotal role of negative controls in confirming on-target effects and provides practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers seeking to enhance the validity of their chemical probe studies.

Understanding Negative Controls: Concepts and Terminology

Defining Negative Controls in Chemical Probe Context

In experimental biology, negative controls are samples treated similarly to experimental samples but not expected to produce a change, thereby demonstrating that observed effects are due to the experimental variable rather than other factors [9]. In the specific context of chemical probe experiments, this concept expands to include several critical components:

- Target-inactive control compounds: Structurally matched analogs that are inactive against the primary target but share similar physicochemical properties [6]

- Orthogonal chemical probes: Distinct chemical structures targeting the same protein that provide complementary evidence for on-target effects [6]

- Experimental negative controls: Samples that leave out essential ingredients or check for effects impossible by the hypothesized mechanism [8]

The power of negative controls lies in their ability to detect confounding and other sources of error that might otherwise lead to incorrect causal inferences about the relationship between target engagement and observed phenotypic effects [8].

The Conceptual Relationship Between Controls and Experimental Outcomes

Current Landscape: Quantitative Evidence of the Problem

The discrepancy between recommended best practices and actual implementation of chemical probes in research is striking. The following data, synthesized from a systematic review of 662 publications, highlights specific areas where improvement is needed across different chemical probes [6]:

Table 1: Compliance with Best Practices in Chemical Probe Usage Across 662 Publications

| Chemical Probe | Primary Target | Publications Analyzed | Used Within Recommended Concentration | Used Matched Inactive Control | Used Orthogonal Probes | Fully Compliant Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNC1999 | EZH2 | 146 | 25% | 7% | 15% | 4% |

| GSK-J4 | KDM6 | 63 | 24% | 2% | 3% | 0% |

| A-485 | CREBBP/p300 | 57 | 12% | 2% | 9% | 2% |

| AMG900 | Aurora kinases | 83 | 51% | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| AZD1152 | Aurora B | 123 | 61% | 0% | 2% | 0% |

| AZD2014 | mTOR | 190 | 69% | 0% | 3% | 0% |

This data reveals two critical patterns: first, the use of recommended concentrations is inconsistent across probes, and second, the implementation of negative controls (inactive analogs) and orthogonal validation is alarmingly low across all probe categories. These deficiencies directly impact the reliability of target validation studies and subsequent drug development efforts.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Critical Questions on Negative Control Implementation

Q: Why is using a chemical probe at high concentrations problematic even with appropriate negative controls?

A: Even the most selective chemical probe will become non-selective if used at high concentrations [6]. The fundamental fitness factors of a quality chemical probe include potency (typically <100 nM), selectivity (≥30-fold against related proteins), and cellular activity at concentrations ideally below 1 μM [6]. When used above recommended concentrations, you increase the risk of engaging off-target proteins, which may lead to misinterpretation of biological effects. Negative controls help identify some off-target effects, but they cannot compensate for concentration-dependent loss of selectivity.

Q: How do I determine the appropriate concentration range for my chemical probe?

A: Always consult expert-curated resources before designing experiments. The Chemical Probes Portal (www.chemicalprobes.org) provides recommended maximum concentrations for specific probes [6]. Additionally, consider conducting preliminary dose-response experiments to establish the minimum concentration that produces the desired on-target effect (e.g., reduction in phosphorylation or changes in gene expression). Use this information to select a concentration just above the threshold for on-target efficacy but well below levels where promiscuous binding may occur.

Q: What should I do if no target-inactive control is available for my chemical probe of interest?

A: When a matched target-inactive control compound is unavailable, strengthen your experimental design through multiple complementary approaches:

- Employ at least two orthogonal chemical probes with different chemical structures that target the same protein [6]

- Use genetic validation methods (CRISPR, RNAi) in parallel to target the same protein

- Include negative control outcomes that are impossible by the hypothesized mechanism [10]

- Conduct extensive off-target profiling if resources permit

Q: My experimental results show the same effect with both the active chemical probe and the target-inactive analog. What does this indicate?

A: This pattern suggests that the observed phenotypic effect is likely not due to engagement with the intended primary target. Possible explanations include:

- Off-target effects common to both compounds due to shared structural elements

- Solvent or formulation artifacts affecting both samples equally

- Assay conditions that are insensitive to the specific target modulation

- Non-specific cytotoxicity at the concentrations used

Troubleshoot by verifying compound purity, testing lower concentrations, and implementing additional control experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario: Inconsistent results between chemical probe and genetic knockdown approaches

Problem Identification: Observed phenotypic effects differ when using chemical probes versus genetic targeting (CRISPR/RNAi) for the same protein.

Possible Explanations and Solutions:

Timing discrepancies: Chemical probes produce rapid inhibition, while genetic approaches require time for protein turnover. Solution: Include multiple time points and consider using degron technologies for faster genetic depletion.

Compensatory mechanisms: Long-term genetic depletion may trigger adaptive responses not seen with acute chemical inhibition. Solution: Use multiple orthogonal chemical probes to confirm findings.

Incomplete target engagement: The chemical probe may not fully inhibit the target at tested concentrations. Solution: Include positive controls demonstrating maximal target engagement and verify cellular activity.

Off-target effects: Either approach might have unrecognized off-target activities. Solution: Employ both target-inactive chemical controls and rescue experiments for genetic approaches.

Scenario: Unexpected phenotypic effects at recommended concentrations

Problem Identification: Phenotypic effects occur that are inconsistent with known target biology when using probes at recommended concentrations.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Verify compound identity and purity: Source compounds from reputable suppliers and confirm identity and purity through analytical methods.

Confirm concentration response: Establish a full dose-response curve rather than relying on a single concentration.

Implement multiple control types:

Employ orthogonal validation: Use a chemically distinct probe targeting the same protein to confirm on-target effects [6].

Experimental Protocols: Best Practices for Robust Experimental Design

Implementing 'The Rule of Two' for Chemical Probe Experiments

The 'rule of two' provides a straightforward framework for enhancing experimental rigor [6]. This approach mandates that every chemical probe experiment should include:

Two Complementary Experimental Elements:

- At least two orthogonal target-engaging probes (different chemical structures), AND/OR

- A pair consisting of an active chemical probe and its matched target-inactive analog

Two Critical Concentration Considerations:

- Use probes at or near their established cellular on-target activity concentration

- Always include a concentration response (at least 3 concentrations) rather than single-point data

Protocol: Validating On-Target Engagement with Negative Controls

Objective: Confirm that observed phenotypic effects result from specific target engagement rather than off-target effects.

Materials:

- Active chemical probe (e.g., UNC1999 for EZH2)

- Matched target-inactive control compound (where available)

- Orthogonal chemical probe with different chemical structure

- Appropriate vehicle control

- Cell lines or model systems relevant to the biological question

Procedure:

- Determine recommended concentrations by consulting the Chemical Probes Portal or primary probe literature [6].

Establish dose-response curves for both active probe and inactive control across a range of concentrations (typically 3-5 concentrations spanning below and above the recommended range).

Include vehicle controls treated with the compound solvent (DMSO, etc.) at the highest concentration used in experimental conditions.

Treat parallel samples with active probe, inactive control, and orthogonal probe at established optimal concentrations.

Measure both target engagement (through direct binding assays, downstream phosphorylation, or substrate accumulation) and phenotypic endpoints.

Compare results across conditions: Specific on-target effects should show concentration-dependent responses with the active probe but not the inactive control, and should be replicated with orthogonal probes.

Expected Outcomes:

- Active probe shows concentration-dependent target modulation and phenotypic effects

- Inactive control shows minimal target engagement and reduced or absent phenotypic effects

- Orthogonal probe recapitulates key findings from the primary active probe

- Vehicle control shows no significant effects

Workflow for Chemical Probe Experiment with Integrated Negative Controls

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Chemical Probe Experiments and Negative Controls

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Design | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | UNC1999 (EZH2 inhibitor), GSK-J4 (KDM6 inhibitor) | Primary tool for modulating specific protein targets | Verify ≥3-star rating on Chemical Probes Portal; check recommended concentrations [6] |

| Target-Inactive Control Compounds | Inactive analogs matched to active chemical probes | Distinguish on-target from off-target effects; control for shared physicochemical properties | Must be structurally similar but biologically inactive against primary target [6] |

| Orthogonal Chemical Probes | Distinct chemical structures targeting same protein | Confirm on-target effects through complementary chemical validation | Should have different chemical scaffolds but similar potency and selectivity [6] |

| Loading Control Antibodies | β-actin, tubulin, GAPDH | Verify equal protein loading in Western blots and other assays | Select controls with different molecular weights than target protein [9] |

| Control Cell Lysates | Lysates from stimulated cells, tissue-derived lysates | Provide positive controls for assay functionality | Ensure lot-to-lot consistency and proper characterization [9] |

| Purified Proteins | Tagged and untagged purified proteins | Serve as positive controls for binding and functional assays | Verify protein integrity and functionality before use [9] |

The implementation of robust negative controls, particularly target-inactive analogs, represents a critical component of rigorous chemical probe experimentation. By adopting the 'rule of two' framework—utilizing either two orthogonal chemical probes or a probe-inactive control pair—researchers can significantly enhance the validity of their target validation studies [6]. The current evidence indicates substantial room for improvement, with only a minute fraction of published studies employing chemical probes with appropriate controls and concentrations.

As the field continues to advance, with initiatives such as Target 2035 aiming to generate high-quality chemical probes for every human protein [11], the foundational principles of careful experimental design remain paramount. Through the consistent application of negative controls and adherence to chemical probe best practices, the research community can strengthen experimental conclusions, enhance reproducibility, and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic agents.

In biomedical research and drug discovery, chemical probes are small molecules designed to selectively bind to and modulate the function of a specific protein target, allowing scientists to decipher that protein's role in health and disease [12]. The validity of these findings is entirely dependent on the quality and specificity of the probes used. A growing crisis of irreproducible research has been linked to the use of poorly validated chemical tools, leading to false leads, wasted resources, and a slowdown in therapeutic development [13] [12]. This technical support center outlines the best practices for probe validation and troubleshooting to ensure research integrity and reproducibility.

The High Stakes: How Poor Probes Undermine Research

Using chemical probes that lack sufficient validation can lead to several critical failures in experimental outcomes, making it difficult to distinguish true biological effects from artifacts.

- Misattribution of Phenotype: Without confirmation that a probe engages its intended target in a living system, any observed phenotypic effects cannot be confidently attributed to the perturbation of the protein of interest. Off-target interactions may be responsible for the results [14] [12].

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio: In imaging applications, particularly in vivo, poorly designed probes are often activated by off-target enzymes or degrade non-specifically. This results in high background signal, low contrast, and an inability to accurately delineate areas of true enzymatic activity, such as tumor margins [15].

- Literature Pollution: The continued use of historic but poorly characterized inhibitors leads to erroneous scientific conclusions that are perpetuated in the literature, making it difficult to discern valid biological mechanisms [13] [12]. One analysis noted that nearly two-thirds of target-validation projects in an industrial setting were halted because in-house findings failed to match published literature, a problem directly linked to data irreproducibility [13].

Establishing the Standard: What Constitutes a High-Quality Chemical Probe

To be considered high-quality and fit for purpose, a chemical probe should meet a set of well-defined criteria. The following table summarizes the key characteristics as defined by expert communities like the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and the Chemical Probes Portal [16] [12].

Table 1: Key Criteria for a High-Quality Chemical Probe

| Criterion | Description | Recommended Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | Strength of the probe's interaction with its intended target in a biochemical assay. | < 100 nM (IC₅₀ or Kᵢ) [12] |

| Cellular Potency | Effective concentration of the probe in a cellular assay. | < 1 µM (EC₅₀) [12] |

| Selectivity | Ability to discriminate between the primary target and closely related proteins (e.g., within the same enzyme family). | > 30-fold selectivity over related targets [12] |

| Target Engagement | Direct, evidenced binding to the intended target in a live cellular environment. | Demonstrated with a direct binding assay [14] [12] |

| Negative Control | Availability of a matched, structurally similar but inactive compound (e.g., an enantiomer). | Used to confirm on-target effects [16] |

A robust validation framework for chemical probes is built upon four key pillars that connect cellular exposure to a functional outcome. The workflow below illustrates this logical progression from ensuring the probe enters the cell to demonstrating a meaningful phenotypic change.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: General Probe Selection and Validation

Q1: What is the single most important experiment to confirm a probe is working in my cellular model? The most critical experiment is a direct target engagement assay in live cells [14] [12]. While measuring downstream changes in substrate or product is useful, these can be influenced by other pathways. Direct binding assays, such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) competitive binding assays, provide unambiguous evidence that your probe is interacting with the intended target in your specific experimental system [14] [16].

Q2: Why is a negative control compound so highly recommended? A negative control compound (e.g., a structurally similar but inactive enantiomer) is crucial for confirming that an observed phenotype is due to on-target inhibition and not an off-target effect [16]. If the active probe produces a phenotype but the inactive control does not, confidence in the result is greatly increased.

Q3: Where can I find expert-curated information on high-quality chemical probes? Two essential open-access resources are:

- The Chemical Probes Portal (chemicalprobes.org): A non-commercial resource where an international scientific advisory board provides reviews and recommendations on the quality and use of specific probes [12].

- The Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) Website: Provides detailed characterization data, including selectivity profiles and crystal structures, for all the chemical probes they develop [16] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Lack of observed phenotypic effect despite using a published probe.

- Potential Cause 1: The probe is not engaging the target in your specific cellular model due to differences in permeability, metabolism, or target expression levels.

- Solution: Perform a target engagement assay in your cell line to verify binding. Titrate the probe concentration to find an effective range [14].

- Potential Cause 2: The probe is not sufficiently potent in your system, or the target protein is not critical for the phenotype under your experimental conditions.

- Solution: Use a different, chemically distinct probe for the same target to corroborate the result. Confirm target expression and essentiality in your model [16].

Problem: High background signal in a fluorescent, enzyme-activated probe during live-cell imaging.

- Potential Cause: Non-specific activation of the probe by off-target enzymes or non-enzymatic degradation in the cellular environment [15].

- Solution: Ensure the probe incorporates design elements for selectivity, such as unnatural amino acids in its recognition sequence. Run control experiments in cells where the target enzyme has been genetically knocked down or inhibited with a highly specific inhibitor to confirm the signal is on-target [15].

Problem: An observed phenotype is not replicated by a second probe for the same target.

- Potential Cause: The first probe has a significant, unappreciated off-target liability that is responsible for the phenotype, not the inhibition of the purported target.

- Solution: This highlights the necessity of using multiple, chemically distinct probes for target validation [16]. Profile the first probe against a broad selectivity panel (e.g., using kinobeads or the KiNativ platform for kinases) to identify potential confounding off-targets [14].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Probe Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Target Engagement with a Cellular Competitive Binding Assay

This methodology, as employed in the development of a JAK3 kinase probe, uses BRET to directly measure competition between a probe and a reference binder in live cells [12].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Engineer cells to stably express the target protein of interest fused to a luciferase (donor).

- Tracer Incubation: Add a reference tracer molecule that is known to bind the target and is conjugated to a fluorescent acceptor dye.

- Probe Competition: Treat the cells with the chemical probe. If the probe binds to the target, it will compete with and displace the tracer.

- Signal Detection: Measure the BRET signal. A decrease in the BRET signal upon probe addition indicates displacement of the tracer and successful target engagement by the probe. This allows for calculation of the probe's apparent intracellular affinity and binding residence time [12].

Protocol 2: Assessing Selectivity Using Chemoproteomic Platforms

For enzyme targets like kinases or hydrolases, broad-scale selectivity profiling is essential to identify off-target interactions [14].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cellular Treatment: Treat native cells or proteomes with either the vehicle (control) or the chemical probe.

- Profiling: Use a platform like Kinobeads (for kinases) or broad-spectrum Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) probes.

- Kinobeads: Lyse the cells and incubate the proteome with bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum kinase inhibitors. The beads pull down a large proportion of the kinome. Bound kinases are then identified and quantified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [14].

- ABPP: Use a cocktail of fluorescently-tagged or bio-orthogonal activity-based probes that react with the active sites of enzymes in a protein family. These are incubated with proteomes from probe- and vehicle-treated cells.

- Analysis: Compare the abundance of proteins pulled down by Kinobeads or labeled by ABPP probes between treated and untreated samples. Proteins whose binding or labeling is reduced in the treated sample are considered engaged by the chemical probe. This provides a quantitative map of on-target and off-target interactions directly in a relevant proteome [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Probe Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Target Engagement Assays | Directly measures probe-target binding in live cells. | BRET-based competition binding; Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [12]. |

| Broad-Spectrum Activity-Based Probes (ABPP) | Pan-reactive reagents that label many members of an enzyme family based on activity. | Competitive ABPP to assess target engagement and selectivity for proteases, kinases, and hydrolases in native proteomes [14]. |

| Photoreactive Probe Analogues | Contain a photoreactive group and a latent affinity handle (e.g., an alkyne) to covalently capture protein targets in cells upon UV irradiation. | Identification of on- and off-targets for reversible binders via click chemistry conjugation to reporter tags [14]. |

| Kinobeads | Bead-immobilized, broad-spectrum kinase inhibitors used to affinity-capture kinases from native proteomes. | LC-MS-based profiling to quantify the engagement of hundreds of kinases by a test inhibitor in a single experiment [14]. |

| Negative Control Compound | A structurally matched but inactive molecule (e.g., inactive enantiomer). | Serves as a critical control to confirm that observed phenotypes are due to on-target activity [16]. |

From Theory to Bench: Methodologies and Applications in Complex Models

FAQs: Understanding Target Engagement Assays

1. What is the core principle behind CETSA?

The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) is based on the biophysical principle that when a small molecule drug binds to its target protein, it often stabilizes the protein's structure. This stabilization reduces the protein's tendency to unfold and aggregate when heated. In a typical experiment, cells or cell lysates containing the target protein are incubated with the drug and then subjected to a range of temperatures. The ligand-bound, stabilized proteins remain soluble at higher temperatures, while unbound proteins denature and precipitate. The amount of remaining soluble protein is then quantified, and a shift in the protein's melting temperature (Tm) indicates successful target engagement [17] [18].

2. How does CETSA differ from traditional Thermal Shift Assays (TSAs)?

The key difference lies in the biological relevance of the sample matrix. Traditional TSAs are performed using purified, recombinant proteins in a simplified buffer system. In contrast, CETSA uses more complex and physiologically relevant samples, such as intact cells, cell lysates, or tissue extracts. This allows CETSA to account for critical factors like a drug's ability to cross the cell membrane, the presence of natural binding partners, and the influence of the native cellular environment on the drug-target interaction [19] [20].

3. When should I use CETSA over other label-free methods like DARTS or SPROX?

The choice of assay depends on your experimental goals and the nature of your target protein. The following table summarizes the key differences to guide your selection:

| Feature | CETSA | DARTS | SPROX |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Detects thermal stabilization upon ligand binding [21]. | Detects protection from protease digestion upon ligand binding [21]. | Detects domain-level stability shifts via methionine oxidation [18]. |

| Sample Type | Live cells, cell lysates, tissues [19] [21]. | Cell lysates, purified proteins [21]. | Cell lysates [18]. |

| Throughput | Medium (Western blot) to High (HT formats/MS) [18] [22]. | Low to Medium [21]. | Medium to High [18]. |

| Key Advantage | Operates in native cellular environments; can detect membrane proteins [18]. | Label-free; no compound modification; cost-effective [21]. | Provides binding site information [18]. |

| Main Limitation | May miss interactions that do not cause thermal stabilization [21]. | Sensitivity depends on protease choice; challenges with low-abundance targets [21]. | Limited to methionine-containing peptides; requires MS expertise [18]. |

4. What are the main CETSA formats and what are they used for?

CETSA has evolved into several key formats, each with specific applications in the drug discovery pipeline [18]:

- *Western Blot CETSA (WB-CETSA):* The original format, ideal for validating known target proteins. It is hypothesis-driven but has limited throughput due to its reliance on specific antibodies.

- *CETSA with High-Throughput Detection (CETSA HT):* Uses homogeneous assays like AlphaScreen or split luciferase (e.g., BiTSA) to enable screening of large compound libraries against a predefined target [23] [22].

- *CETSA with Mass Spectrometry (MS-CETSA or TPP):* Allows for proteome-wide profiling by quantifying thermal stability shifts for thousands of proteins simultaneously. This is powerful for unbiased target deconvolution and off-target identification [19] [18].

- *Isothermal Dose-Response Fingerprint CETSA (ITDRF-CETSA):* Instead of a temperature gradient, a single challenging temperature is used while varying the drug concentration. This format is excellent for generating dose-response curves and ranking compound affinities (EC50) [23] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common CETSA Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Irregular or Noisy Melt Curves in DSF/CETSA

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Compound Interference: The test compound may be intrinsically fluorescent, interact with the fluorescent dye (e.g., SyproOrange), or be insoluble at the tested concentration [20]. Visually inspect compounds for color and test for intrinsic fluorescence before the experiment.

- Incompatible Buffer Components: Detergents or additives that increase buffer viscosity can increase background fluorescence [20]. Review the compatibility of all buffer components with your detection method and consider switching to a more compatible buffer.

- Protein Instability: The target protein may be unstable or aggregated at ambient temperature in the chosen buffer [20]. Optimize the protein buffer to ensure the protein is stable and soluble before the experiment begins.

Problem 2: No Observed Thermal Shift in Live-Cell CETSA

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cell Membrane Impermeability: The compound may not efficiently cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target [20]. Use a lysate-based CETSA experiment to bypass the permeability issue. If a shift is observed in lysates but not in intact cells, poor permeability is likely the cause.

- Insufficient Drug-Target Engagement: The compound's affinity might be too low, or the incubation time might be too short to allow for adequate cellular uptake and binding [20]. Increase the compound concentration and/or incubation time. Confirm that the chosen temperature for an ITDRF experiment is appropriate based on a melt curve of the unliganded protein [23].

- Inactive Biological System: The protein's thermal stability can be influenced by its cellular state (e.g., post-translational modifications, binding to endogenous ligands) [23]. Ensure cells are healthy and cultured under appropriate conditions.

Problem 3: High Background or Non-Specific Signals

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient Removal of Precipitated Protein: Centrifugation speed or time may be insufficient to fully pellet denatured aggregates [20]. Ensure centrifugation is performed at high speed (e.g., 20,000g) for a sufficient duration at 4°C.

- Antibody Specificity: The antibody may not be specific enough for the native, folded protein in a complex lysate [23]. Validate the antibody for specificity in the CETSA context. For MS-based CETSA, optimize sample preparation to reduce complexity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic Western Blot CETSA Melt Curve Experiment

This protocol outlines the steps to generate a thermal melt curve for a target protein in intact cells [23] [18].

- Cell Preparation and Treatment: Plate the desired cell line expressing the target protein. When cells reach the appropriate confluency, add your compound of interest or a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO). Incubate under normal culture conditions to allow for compound uptake and binding.

- Heating: Harvest the cells and aliquot them into PCR tubes. Subject each aliquot to a different temperature in a gradient (e.g., from 37°C to 64°C in 3°C intervals) for a set time (e.g., 3 minutes) using a thermal cycler [24].

- Cell Lysis and Soluble Protein Extraction: Lyse the heated cells using multiple freeze-thaw cycles (e.g., flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by thawing at 37°C) [18]. Remove the denatured and aggregated proteins by centrifugation at high speed (e.g., 20,000g for 20 minutes at 4°C).

- Protein Detection and Quantification: Transfer the supernatant, which contains the heat-stable soluble protein, to a new tube. Separate the proteins by SDS-PAGE and perform a Western blot using an antibody specific for your target protein.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the band intensity from the Western blot using densitometry. Plot the relative amount of soluble protein against temperature to generate a melt curve. A rightward shift in the curve for the drug-treated sample indicates thermal stabilization and successful target engagement.

Protocol 2: ITDRF-CETSA for Dose-Response Assessment

This protocol is used to determine the potency (EC50) of a compound [23] [18].

- Dose Preparation: Prepare a serial dilution of your test compound across a wide concentration range.

- Cell Treatment and Heating: Treat intact cells or cell lysates with each concentration of the compound. Based on a prior melt curve experiment, choose a single challenging temperature near the Tm of the unbound protein. Heat all samples at this fixed temperature.

- Analysis: Process the samples as in the basic CETSA protocol (steps 3 and 4) to quantify the remaining soluble target protein at each compound concentration.

- Data Analysis: Plot the relative amount of soluble protein against the logarithm of the compound concentration. Fit a sigmoidal dose-response curve to the data to calculate the EC50 value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Target Engagement Assays |

|---|---|

| Polarity-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., SyproOrange) | Used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to bind exposed hydrophobic regions of unfolding proteins, providing a fluorescent signal for melt curve generation [20]. |

| High-Quality Specific Antibodies | Essential for detecting and quantifying the target protein in Western Blot (WB) CETSA and bead-based AlphaScreen CETSA [23] [18]. |

| Split Luciferase Systems (e.g., HiBiT/LgBiT) | Enables antibody-free, high-throughput CETSA (e.g., BiTSA). A small tag (HiBiT) is engineered onto the target protein; upon binding its partner (LgBiT), luciferase activity is restored, which is lost upon heat denaturation [19]. |

| Isobaric Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Multiplexing reagents used in MS-CETSA/TPP to label peptides from different temperature or concentration conditions, allowing for simultaneous quantification in a single MS run [19]. |

| Heat-Stable Loading Control Proteins (e.g., SOD1) | Proteins that remain stable across a wide temperature range, used in Western blot-based TSAs to normalize for sample loading and preparation variability [20]. |

Assay Workflow and Selection Diagrams

Leveraging Chemical Proteomics for Unbiased Target Identification

Chemical proteomics is a powerful approach in chemical biology that uses small-molecule probes to map interactions between small molecules and proteins on a proteome-wide scale. This methodology serves as a critical bridge between phenotypic drug discovery and target-based approaches, enabling the unbiased identification of molecular targets directly in complex biological systems [25] [26]. Unlike traditional reductionist methods that investigate individual proteins in isolation, chemical proteomics allows for the systematic exploration of protein functions, activities, and interactions across entire proteomes [25].

The fundamental value of chemical proteomics in target identification lies in its ability to profile functional protein activities rather than merely measuring protein abundance. Phenotypic traits emerge from the interplay between protein abundance and functional activity, making the accurate measurement of activity a critical but challenging task in understanding biological systems [25]. By using chemically engineered probes that engage with proteins based on their functional state, chemical proteomics provides initial insights into the activities of specific target proteins and their involvement in disease pathways [25] [26].

For researchers engaged in chemical probe target validation, chemical proteomics offers distinct advantages over conventional methods. It enables the comprehensive identification of both on-target and off-target interactions, provides crucial information about drug safety and efficacy, and facilitates the characterization of targets for natural products with complex mechanisms of action [27] [26]. This approach has become particularly valuable for understanding the molecular mechanisms of natural products in cancer treatment, where more than 60% of current anticancer agents are derived from natural origins or their structural prototypes [27].

Table: Comparison of Major Chemical Proteomics Approaches for Target Identification

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity-Based Pull-Down [26] [28] | Compound immobilized on solid support captures binding proteins from lysate | Workhorse application; most target classes | High spatial resistance may lose weak binders; requires immobilizable high-affinity probe |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) [25] [28] | Reactive group covalently binds enzyme active sites; reporter tag enables detection | Enzyme superfamilies; profiling functional states | Requires reactive residues in accessible regions; warhead design critical |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) [26] [28] | Photoreactive group forms covalent crosslinks with proximal amino acids upon UV exposure | Membrane proteins; transient interactions; weak binders | Potential for non-specific labeling; optimization of photoreactive group placement needed |

| Label-Free Methods (e.g., CETSA, DARTS) [27] [20] [28] | Measures changes in protein stability or protease sensitivity upon compound binding | Native conditions without probe modification | Challenging for low-abundance proteins, large proteins, and membrane proteins |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Probe Design and Synthesis Issues

Problem: Low Binding Affinity or Specificity After Probe Modification When a chemical probe derived from your active compound shows reduced binding affinity or lost specificity, the issue often stems from improper attachment of the reporter or enrichment tags. The modification may sterically hinder the compound's interaction with its target or alter its physicochemical properties [26] [28].

- Solution 1: Optimize linker length and composition. Incorporate flexible linkers (e.g., PEG-based spacers) or cleavable linkers (e.g., disulfide bonds) to reduce steric hindrance while maintaining sufficient distance between the active compound and the bulky tag [26].

- Solution 2: Employ bioorthogonal click chemistry. Use minimal terminal alkyne or azide tags for in situ labeling followed by copper-catalyzed or strain-promoted click chemistry with detection tags after the binding event. This preserves the native structure and activity of the compound during cellular uptake and target engagement [25] [26].

- Solution 3: Utilize photoaffinity labeling (PAL). Incorporate photoreactive groups (diazirines, benzophenones) that form covalent bonds with target proteins only upon UV irradiation. This captures transient interactions and allows for more flexible positioning of the reactive group [26] [28].

Problem: High Background Noise in Enrichment Experiments Excessive non-specific binding during affinity pull-down experiments results in high background and obscures identification of true targets.

- Solution 1: Implement competitive blocking. Pre-incubate with excess unmodified compound during the pull-down to compete for specific binding sites. Proteins still enriched in both experimental and control groups likely represent non-specific binders [26].

- Solution 2: Optimize wash stringency. Increase salt concentration (e.g., 300-500 mM NaCl), include mild detergents (e.g., 0.1% CHAPS), or add competitive reagents (e.g., 0.1-1% BSA) in wash buffers to reduce non-specific interactions while maintaining specific binding [26].

- Solution 3: Use different solid supports. Switch from agarose beads to magnetic beads or surface-functionalized plates to minimize hydrophobic interactions with the matrix itself [26].

Sample Preparation and Handling Problems

Problem: Low Protein Yield or Integrity After Cell Lysis Inconsistent protein recovery or degradation during sample preparation compromises downstream chemical proteomics applications.

- Solution 1: Avoid surfactant-based lysis methods. Replace Triton X-100, Tween, or Nonidet P-40 with mass-spectrometry compatible detergents (e.g., n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) or detergent-free lysis methods (e.g., mechanical disruption, freeze-thaw cycles) to prevent polymer contamination that interferes with MS detection [29].

- Solution 2: Include protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Use fresh inhibitor cocktails tailored to your cell type and protein classes of interest. Consider temperature control during lysis (maintain at 4°C) to preserve native protein states and modifications [29].

- Solution 3: Optimize protein concentration and storage. Determine optimal protein concentration for labeling (typically 1-5 mg/mL) and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting samples. Use "high-recovery" tubes pre-treated with BSA or other blocking proteins to prevent adsorption losses [29].

Problem: Keratin and Other Common Contaminants Keratin contamination from skin, hair, or dust accounts for more than 25% of peptide content in some proteomics samples, masking low-abundance targets [29].

- Solution 1: Implement strict contamination controls. Wear gloves at all times (though consider removing after protein digestion to avoid polymer contamination from gloves), use laminar flow hoods for sample preparation, and avoid natural fiber clothing (wool) in the laboratory [29].

- Solution 2: Maintain dedicated equipment and reagents. Use LC-MS dedicated water and mobile phase bottles that are never exposed to detergents. Filter buffers through MS-compatible filters and use high-purity solvents and water less than 48 hours after opening or production [29].

- Solution 3: Include contaminant databases in MS search parameters. Update your search algorithms to include common contaminant proteins for proper identification and filtering during data analysis [29].

Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis Challenges

Problem: Poor LC-MS Performance and Signal Suppression Liquid chromatography separation quality deteriorates or mass spectrometry signal is suppressed, reducing protein identification rates.

- Solution 1: Avoid TFA in mobile phases. While trifluoroacetic acid improves chromatographic peak shape, it dramatically suppresses peptide ionization. Use formic acid (0.1%) for mobile phases instead, and if needed, add TFA only to the sample to enhance hydrophilic peptide retention on pre-columns [29].

- Solution 2: Implement effective desalting. Use reversed-phase solid-phase extraction or stage tips to remove urea, salts, and other ion-suppressing contaminants before LC-MS analysis. Avoid complete drying of samples during concentration steps to prevent irreversible adsorption to vessel surfaces [29].

- Solution 3: Regularly maintain and calibrate MS instrumentation. Establish routine cleaning schedules for ion sources, replace worn capillaries and emitters, and use fresh peptide calibration standards applied via non-metal syringes (e.g., glass syringes with PEEK capillaries) to prevent peptide loss through adsorption to metal surfaces [29].

Problem: High False Discovery Rates in Target Identification Data analysis yields numerous potential targets that cannot be validated in follow-up experiments, indicating potential false positives.

- Solution 1: Implement rigorous statistical filtering. Apply strict cutoff criteria (e.g., fold-change > 2, p-value < 0.05) and require multiple unique peptides per protein identification. Use significance analysis algorithms like SAINT or Fisher's exact test for affinity enrichment data [30].

- Solution 2: Incorporate orthogonal validation early. Combine chemical proteomics with label-free methods like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) or Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) to confirm target engagement in physiological conditions without probe modification [27] [20] [28].

- Solution 3: Use biological replicates and controls. Include at least three biological replicates and appropriate controls (vehicle-treated, competition with unmodified compound, irrelevant probe) to distinguish specific binders from non-specific interactions [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) over affinity-based pull-down for target identification?

ABPP is particularly suitable when: (1) You're targeting entire enzyme families sharing common mechanistic features; (2) You want information about functional activity states beyond mere protein abundance; (3) Your target proteins contain reactive nucleophilic residues (serine, cysteine, etc.) accessible to covalent warheads. Affinity-based pull-down is more appropriate for: (1) Non-enzyme targets without defined catalytic mechanisms; (2) Compounds with sufficiently high binding affinity (typically < 1 µM); (3) Situations where you can create an immobilized probe without significant loss of activity [25] [28].

Q2: How can I validate targets identified through chemical proteomics in biologically relevant systems?

Implement a multi-step validation workflow: First, confirm direct binding using biophysical methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Thermal Shift Assays (TSA). Second, demonstrate functional relevance through genetic approaches (CRISPR knockout, RNAi knockdown) showing that target modulation reproduces the compound's phenotypic effects. Third, establish quantitative correlation between target engagement and functional response using techniques like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) for cellular target engagement or enzyme activity assays for functional consequences [20] [28] [31].

Q3: What are the best practices for handling membrane protein targets in chemical proteomics studies?

Membrane proteins present special challenges due to their hydrophobicity and tendency to aggregate. Recommended approaches include: (1) Using mild detergents (dodecyl maltoside, digitonin) for solubilization that maintain protein structure and activity; (2) Incorporating photoaffinity labeling with photoreactive groups to capture interactions before solubilization; (3) Implementing chemical tagging methods like cell-surface biotinylation to specifically enrich for plasma membrane proteins; (4) Adding organic solvents (methanol, chloroform) or organic acids (formic acid) during sample processing to improve solubility while being mindful of potential protein modifications [30].

Q4: How can I address the challenge of low-abundance targets in complex proteomes?

Several strategies can enhance detection of low-abundance targets: (1) Implement extensive fractionation at both protein and peptide levels (SDS-PAGE, strong cation exchange); (2) Use depletion methods to remove high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins from serum samples) while being cautious of concomitant removal of bound low-abundance proteins; (3) Apply data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry methods that provide more comprehensive coverage; (4) Increase sample loading and use advanced MS instrumentation with higher sensitivity and faster scan rates; (5) Employ chemical pre-enrichment strategies like phosphopeptide enrichment for signaling studies [30].

Q5: What controls are essential for interpreting chemical proteomics experiments confidently?

Robust experimental design should include: (1) Competition controls with excess unmodified compound to establish specific binding; (2) Structural analogs with known inactivity to assess structure-activity relationships; (3) Vehicle-only treated controls to establish baseline; (4) Bead-only or matrix-only controls to identify proteins that non-specifically bind to the solid support; (5) Time-course or concentration-dependence experiments to establish binding kinetics and affinity; (6) Comparison across different cell types or conditions where target expression or compound activity is expected to differ [26].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Standard Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) Workflow

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) uses chemical probes containing three key elements: a reactive warhead that covalently targets enzyme active sites, a linker region, and a reporter tag (e.g., biotin for enrichment or fluorophore for visualization) [25]. This methodology enables monitoring of enzyme activity states rather than mere abundance across entire enzyme families.

ABPP Experimental Workflow for Target Identification

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Proteome Preparation: Prepare proteome extracts from cells or tissues of interest using detergent-free lysis buffers (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitors. Maintain protein concentration at 1-2 mg/mL for optimal labeling [25] [29].

- ABPP Probe Labeling: Incubate proteome (50-100 µg) with ABPP probe (1-10 µM final concentration) in labeling buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 37°C. Include control samples with vehicle only and competition samples with excess unmodified compound [25].

- Analysis Branch 1 - In-gel Fluorescence: Resolve labeled proteins by SDS-PAGE, scan gel for fluorescence signal using appropriate wavelengths (e.g., 488 nm excitation for TAMRA-labeled probes). This provides rapid assessment of labeling patterns and specificity [25].

- Analysis Branch 2 - Affinity Enrichment and MS Identification: For biotinylated probes, incubate labeled proteome with streptavidin-agarose beads (20-50 µL bead slurry per 100 µg protein) for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle rotation. Wash beads extensively (3-5 times with 1 mL labeling buffer containing 0.2% SDS) to remove non-specifically bound proteins [25].

- On-bead Digestion: Denature beads in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate with 8 M urea, reduce with 5 mM DTT (30 minutes, 37°C), alkylate with 15 mM iodoacetamide (30 minutes, room temperature in dark), and digest with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C [25].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Desalt peptides and analyze by nano-liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry using data-dependent acquisition methods. Use 60-120 minute gradients for peptide separation [25].

- Data Processing: Search MS/MS spectra against appropriate protein database using search engines like MaxQuant or Proteome Discoverer. Identify specifically enriched proteins by comparing abundance in probe-labeled samples versus vehicle and competition controls [25].

Label-Free Target Engagement Validation Workflow

Label-free methods like Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) and Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) enable target engagement studies without chemical modification of the compound, preserving its native structure and function [20]. These approaches are particularly valuable for validating targets identified through probe-based methods.

CETSA Workflow for Label-Free Target Engagement

Detailed CETSA Protocol:

- Compound Treatment: Treat intact cells (1-2 million cells per condition) with compound of interest or vehicle control for predetermined time (typically 1-4 hours) at physiologically relevant concentrations. Include multiple concentrations for dose-response studies [20].

- Heat Exposure: Aliquot cell suspensions into PCR tubes and expose to a temperature gradient (e.g., 8-10 points between 40°C and 65°C) for 3 minutes in a thermal cycler, followed by cooling to room temperature [20].

- Cell Lysis and Soluble Protein Extraction: Lyse heated cells using freeze-thaw cycles (3 repetitions in liquid nitrogen) or detergent-containing lysis buffers. Remove aggregated proteins by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C [20].

- Protein Quantification:

- Western Blot Approach: Separate soluble proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membranes, and probe with antibodies against target protein of interest. Include loading controls (e.g., heat-stable proteins like SOD1 or GAPDH) for normalization [20].

- MS-Based Proteomics Approach: Digest soluble proteins with trypsin, label with TMT isobaric tags if multiplexing, and analyze by LC-MS/MS. Quantify protein abundance across temperature points [20].

- Data Analysis: Generate melt curves by plotting soluble protein fraction remaining versus temperature. Fit curves to sigmoidal Boltzmann equation to calculate melting temperature (Tm). Significant rightward shift in Tm (typically >2°C) in compound-treated samples indicates thermal stabilization and direct target engagement [20].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Proteomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes [25] | Fluorophosphonate (FP)-biotin, DCG-04-TAMRA | Covalent labeling of enzyme active sites (serine hydrolases, cysteine proteases) | Warhead specificity dictates target class coverage; optimize concentration and time |

| Bioorthogonal Handles [26] | Alkyne, azide, bicyclononyne (BCN) | Minimal chemical tags for subsequent click chemistry conjugation | Copper-catalyzed click may be cytotoxic; strain-promoted alternatives better for live cells |

| Photoaffinity Groups [26] | Diazirine, benzophenone, aryl azides | UV-activated covalent crosslinking for capturing transient interactions | Diazirines offer smaller size; benzophenones greater stability; optimize UV exposure time |

| Solid Supports [26] | Streptavidin-magnetic beads, NHS-activated agarose | Affinity enrichment of probe-bound proteins | Magnetic beads easier to handle; test binding capacity; include bead-only controls |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Reagents [29] | Sequence-grade trypsin/Lys-C, HPLC-grade solvents, MS-compatible detergents | Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS analysis | Avoid polymers, ion-pairing agents (TFA) that suppress ionization; use fresh reagents |

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

The integration of chemical proteomics with artificial intelligence and machine learning represents a transformative advancement in target identification and validation. AI-driven models can process complex proteomic datasets to predict small molecule-protein interactions, identify patterns not readily apparent through conventional analysis, and prioritize targets for experimental validation [27]. This integration is particularly valuable for understanding the polypharmacology of natural products, which often exert their therapeutic effects through interactions with multiple protein targets simultaneously [27].

Chemical proteomics has also proven instrumental in addressing the challenge of off-target effects that account for approximately 58% of late-stage clinical trial failures [31]. By comprehensively mapping the interactome of drug candidates early in development, researchers can identify potential off-target interactions that may lead to toxicity or unwanted side effects. This proactive approach to safety assessment enables medicinal chemists to redesign compounds for improved selectivity before committing significant resources to clinical development [26] [31].

The continued evolution of chemical proteomics methodologies, including more sophisticated probe designs, enhanced mass spectrometry instrumentation, and advanced computational integration, promises to further accelerate the identification and validation of therapeutic targets. These advancements are particularly crucial for tackling historically "undruggable" targets like transcription factors and RAS family proteins, where chemical proteomics approaches have already contributed to breakthrough therapies [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of using patient-derived primary cells over traditional cell lines for chemical probe validation?

Patient-derived primary cells, such as organoids and tumor spheroids, retain the genetic, phenotypic, and functional characteristics of the original patient tissue, including native tissue architecture, cellular heterogeneity, and patient-specific drug responses [32] [33]. This makes them superior to traditional 2D cell lines for preclinical target validation, as they more accurately recapitulate the human in vivo environment, leading to more reliable and translatable results when testing the efficacy and selectivity of chemical probes [34] [33].

FAQ 2: How can I ensure the quality of a chemical probe when using it in a complex primary cell system?

A high-quality chemical probe should meet stringent criteria, including potency (<100 nM in a biochemical assay), excellent selectivity (>30-fold over related proteins), and demonstrated cellular activity (<1 µM) [35] [12] [36]. It is critical to use appropriate negative controls, such as structurally similar but inactive analogs, and whenever possible, to employ a second, structurally distinct "orthogonal" probe to confirm that observed phenotypes are due to on-target effects [35] [12]. Furthermore, you should always verify target engagement within your specific primary cell system, as protein expression and accessibility can vary [35] [12].

FAQ 3: What are the most common challenges in establishing cultures of patient-derived primary cells, and how can they be mitigated?

Establishing primary cultures is fraught with challenges, including low culture initiation success rates, difficulty in maintaining original tumor heterogeneity, and microbial contamination [32] [33]. These can be mitigated by:

- Prompt and Proper Tissue Processing: Process samples immediately or use validated short-term storage methods to preserve cell viability [32].

- Using a Physiologically Relevant Matrix: Employ 3D culture systems like Matrigel to support the growth of complex structures like organoids and spheroids [32] [33].

- Rigorous Aseptic Technique and Quality Control: Implement routine testing for authentication (e.g., STR profiling) and contamination (e.g., mycoplasma) to ensure culture purity and identity [37].

FAQ 4: My chemical probe works in conventional cell lines but not in my patient-derived organoid model. What could be the reason?