Chemical Biology: Foundational Principles, Methodologies, and Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to chemical biology, an interdisciplinary field that applies chemical techniques and principles to study and manipulate biological systems.

Chemical Biology: Foundational Principles, Methodologies, and Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to chemical biology, an interdisciplinary field that applies chemical techniques and principles to study and manipulate biological systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts of the discipline, details key methodological approaches and their real-world applications in biomedicine, discusses strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and reviews methods for validating and comparing tools. By synthesizing current research and trends, this overview aims to serve as a resource for leveraging chemical biology to advance therapeutic discovery and fundamental biological understanding.

Defining Chemical Biology: Core Concepts and Historical Evolution

What is Chemical Biology? Distinguishing it from Biochemistry and Biological Chemistry

Chemical biology is an interdisciplinary field that uses chemical techniques, tools, and principles to study and manipulate biological systems. The core of chemical biology lies in the synergistic application of chemistry to address biological questions, often through the design and use of small molecules, novel chemical methods, and synthetic approaches. As the field has evolved, a precise definition has remained challenging, but a unifying theme is the use of chemical matter to interface with biological systems in precise and predictable ways to unravel biological complexity [1] [2]. Chemical biologists often invent new tools and methods to pursue biological research from a chemist's perspective, a approach not hampered by rigid definitions, allowing the field to freely embrace new ideas [1]. In essence, chemical biology involves "viewing the world around us, the living organisms and their environment, through the lens of a chemist, and taking advantage of the unique ability of chemists to not only study but also create new forms of matter at the molecular level for societal benefit" [1].

Core Principles and the Chemical Biology Platform

The practice of chemical biology is anchored in several core principles and is often operationalized through what is known as the chemical biology platform. This platform is an organizational approach designed to optimize drug target identification and validation, and to improve the safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [3]. It connects a series of strategic steps to determine whether a newly developed compound could translate into clinical benefit, heavily leveraging systems biology techniques like proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics [3].

The historical development of this platform involved key steps [3]:

- Bridging Chemistry and Pharmacology: The initial step involved fostering collaboration between chemists, who synthesize and modify potential therapeutic agents, and pharmacologists/biologists, who use animal models and cellular systems to demonstrate therapeutic benefit and pharmacokinetic properties.

- Introducing Clinical Biology: This phase focused on using biomarkers and human disease models to demonstrate a drug's effect and early signs of clinical efficacy before committing to large, costly late-stage trials.

- Integrating Modern Tools: The platform matured by incorporating genomics, combinatorial chemistry, structural biology, high-throughput screening, and various cellular assays (e.g., high-content analysis, reporter gene assays) to find and validate targets [3].

Table 1: Core Principles of Chemical Biology

| Principle | Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Tool-Driven Discovery | Focused on developing new molecules or approaches (e.g., small molecules, chemical probes) purposefully designed to address specific gaps in biological knowledge [1]. | 'Tool making' occurs hand-in-hand with 'tool using' [1]. |

| Mechanistic Inquiry | Aims to understand the fundamental mechanisms of biological processes at the molecular level using chemical tools [1]. | Goes beyond descriptive observation to uncover chemical mechanisms in intact systems [1]. |

| Perturbation and Control | Uses small molecules to perturb biological systems (proteins, nucleic acids, cellular components) to explore function and change biological outcomes [4]. | Seeks to control and modulate biological processes, especially disease-relevant pathways [1]. |

| Synthetic and Bio-Orthogonal Chemistry | Applies synthetic chemistry to create probes and utilizes bio-orthogonal reactions (that don't interfere with native biology) for studying processes in living systems [4] [5]. | Allows for selective reactions within living organisms for imaging, drug delivery, and more [5]. |

Distinguishing Between Related Disciplines

While chemical biology, biochemistry, and biological chemistry all operate at the chemistry-biology interface, their focus, goals, and primary tools differ.

Chemical Biology vs. Biochemistry: Biochemistry is traditionally defined as the study of chemical processes and substances within living organisms, often focusing on the structures and functions of biological macromolecules and metabolic pathways. A key distinction is that "biochemistry is usually defined as a disassembled and reconstituted system of biomolecules whereas chemical biology might be targeting or attempting to understand chemistry in intact cells, tissues or whole animal systems" [1]. Biochemistry has a more vertical focus on the discipline-specific questions of biological chemistry, while chemical biology has a more horizontal focus, borrowing tools from many fields to study biological questions [1].

Chemical Biology vs. Biological Chemistry: Biological Chemistry is often used as a synonym for Biochemistry, focusing on the chemistry of biological molecules and processes. Chemical biology is frequently described as being more interventional and tool-oriented. As one scientist defines it, "Chemical biology is using biology to do new chemistry and using chemistry to probe biology" [1]. It is a mindset of addressing biological problems with a chemical approach, often by creating molecules that nature does not [1] [2].

Table 2: Distinguishing Chemical Biology, Biochemistry, and Biological Chemistry

| Feature | Chemical Biology | Biochemistry | Biological Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Applying chemistry to probe and manipulate biological systems [1] [6]. | Studying chemical processes and substances within living organisms [4]. | The chemistry of biological molecules and processes. |

| Core Goal | To learn new biology by developing and applying chemical tools [1] [2]. | To understand the chemical principles of life. | To understand the chemical structures and reactions in biological systems. |

| Typical Approach | Tool-oriented, interventional, and perturbative [1] [4]. | Analytical and descriptive of natural systems. | Analytical and mechanistic. |

| Characteristic Tools | Small molecule probes, bio-orthogonal chemistry, combinatorial chemistry, high-throughput screening [4] [5]. | Protein purification, enzyme kinetics, metabolic pathway analysis. | Spectroscopic methods, molecular structure analysis, kinetics. |

| System Context | Often targets intact cells, tissues, or whole organisms [1]. | Often uses disassembled and reconstituted systems [1]. | Can span from isolated molecules to cellular systems. |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Chemical biology relies on a suite of powerful methodologies for probing biological systems.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Assay Design

HTS is a process used to rapidly screen thousands of compounds for therapeutic potential. It utilizes automated, robotic processes to run multiple assays in parallel. The two key characteristics are the use of fast assays and massively parallel experimentation, enabled by a large number of wells (e.g., 96, 384, or 1536-well plates) and automation [4].

- Protocol Outline:

- Target Selection: A biologically relevant target (e.g., an enzyme, receptor, or pathway) is identified.

- Assay Development: A biochemical or cell-based assay is designed to report on the target's activity. This often uses fluorescent, luminescent, or colorimetric readouts.

- Library Exposure: A diverse library of small molecules is added to the assay plates via automated liquid handling.

- Incubation and Reading: Plates are incubated under controlled conditions and then read by a plate reader to quantify the signal.

- Hit Identification: Compounds that produce a significant change in signal ("hits") are identified using statistical analysis for further validation.

Combinatorial Chemistry for Library Synthesis

This methodology enables the rapid synthesis of a large library of compounds (a "chemical library") by combining a set of building blocks in different permutations. This is essential for providing the large numbers of compounds needed for HTS [4].

- Protocol Outline (Solid-Phase Synthesis):

- Attachment: A core scaffold or first building block is covalently attached to solid support beads.

- Division-Coupling-Recombination (Split & Pool):

- Divide: The beads are divided into several equal portions.

- Couple: Each portion is reacted with a different second building block.

- Recombine: All portions of beads are mixed together.

- Repetition: The divide-couple-recombine cycle is repeated with additional sets of building blocks.

- Cleavage: The final compounds are cleaved from the solid support, yielding a library where each molecule in the library is a unique combination of the building blocks.

Bio-Orthogonal Chemistry

Bio-orthogonal chemistry involves chemical reactions that can occur inside living systems without interfering with native biochemical processes. Developed by Carolyn Bertozzi, who won the Nobel Prize for this work, it is crucial for labeling and tracking molecules in cells [4] [5]. A prime example is the strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloaddition, which is favorable, quick, and uses functional groups not found in cells [4].

- Protocol Outline (For Live-Cell Labeling):

- Metabolic Incorporation: A metabolite tagged with a bio-orthogonal functional group (e.g., an azide) is fed to cells. The cells use this tagged building block in their natural biosynthetic pathways, incorporating the azide into the target biomolecule (e.g., a glycoprotein).

- Washing: Excess tagged metabolite is washed away.

- Click Reaction: A detection reagent containing a complementary bio-orthogonal group (e.g., a strained alkyne linked to a fluorophore) is added to the cells.

- Visualization: The rapid and selective "click" reaction between the azide and alkyne labels the target biomolecule with the fluorophore, allowing its visualization by microscopy.

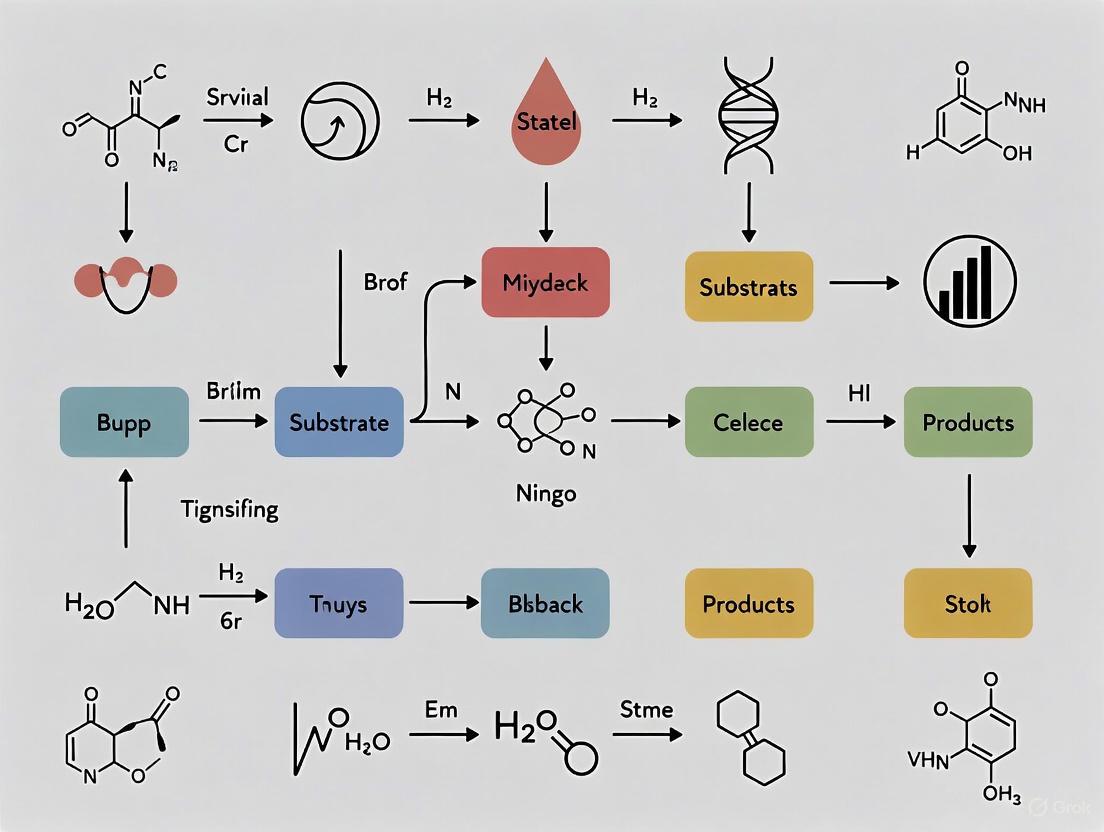

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow of a chemical biology investigation, from tool creation to biological insight.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Chemical biology research depends on a specific toolkit of reagents and materials to design, execute, and analyze experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Chemical Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function in Chemical Biology |

|---|---|

| Small Molecule Probe | A synthetically designed molecule used to perturb a specific biological target (e.g., a protein) to investigate its function [1]. |

| Chemical Library | A collection of hundreds to millions of small molecules, often synthesized via combinatorial chemistry, used for high-throughput screening to discover initial "hit" compounds [4]. |

| Bio-Orthogonal Reagents | Pairs of chemically reactive groups (e.g., azides and strained alkynes) that react specifically and rapidly with each other in living systems, enabling labeling and tracking of biomolecules [4] [5]. |

| Lead Compound | An existing compound (from nature or prior screening) with a known effect, used as a starting point for chemical modification to derive novel therapeutic candidates [4]. |

| Reporter Assays | Reagents (e.g., luciferase, fluorescent proteins) used in cell-based assays to report on the activity of a biological pathway or target in response to a chemical tool [3]. |

| CETSA Reagents | Components for the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay, used to validate direct drug-target engagement in intact cells and tissues by measuring thermal stabilization of the target protein [7]. |

Case Study: Chemical Biology in Action – The Brainwashing of Bees

A case study on bee social hierarchy illustrates classic chemical biology principles. The Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP), secreted by the queen bee, maintains colony structure. A key component of QMP is homovanillyl alcohol (HVA), which impairs the formation of aversive memories in young worker bees [4].

- The Biological Question: How does QMP alter the learning behavior of young worker bees?

- Chemical Insight: The structure of HVA is strikingly similar to the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is essential for learning in insects [4].

- The Hypothesis: HVA, due to its structural similarity, interferes with dopamine signaling by competing for the dopamine receptor binding site.

- Experimental Validation: Researchers confirmed that HVA exposure reduces brain dopamine levels and receptor gene expression, and behaviorally impairs aversive learning. This is a classic example of a small molecule (HVA) from nature being used as a probe to understand a complex biological phenomenon (social behavior) [4].

- Therapeutic Potential: This discovery presents HVA as a lead compound for developing therapeutics aimed at modulating dopamine levels in human diseases like Parkinson's or schizophrenia [4].

The diagram below illustrates the molecular mechanism by which HVA is proposed to exert its effect.

Current Trends and Future Outlook

Chemical biology continues to evolve, powerfully intersecting with modern drug discovery and technology. Key trends defining its current and future impact include:

- AI and Machine Learning: AI has become a foundational capability, accelerating target prediction, compound prioritization, and virtual screening. For example, generative AI and deep graph networks are now used to design thousands of virtual analogs and optimize potency in compressed timelines [7] [8].

- Targeted Protein Degradation: Technologies like PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) are a direct application of chemical biology. These small molecules hijack the cell's natural degradation machinery to remove specific disease-causing proteins, opening up new therapeutic avenues [8].

- Advanced Target Engagement: Methods like CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) provide direct, physiologically relevant confirmation that a drug molecule is engaging its intended target inside intact cells, de-risking drug development [7].

- Precision Gene Editing: The application of CRISPR technology, especially rapid-response, personalized CRISPR therapies, represents the cutting edge of biological manipulation, a core aspiration of chemical biology [8].

- Integration with Multi-Omics: The chemical biology platform increasingly leverages systems biology, integrating data from proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics to understand the full network effects of chemical perturbations [3].

In conclusion, chemical biology is a dynamic and transformative discipline distinguished by its tool-oriented, interventional approach to understanding biology. By leveraging the precision of chemistry to create probes and perturb biological systems, it provides unique insights that are central to modern therapeutic discovery and fundamental biological research.

Chemical biology represents a powerful, interdisciplinary field that uses synthetic chemistry to develop tools for interrogating and manipulating biological systems. The central dogma of this discipline is to use the principles of chemistry to answer fundamental questions in biology and advance human medicine [9]. This approach primarily relies on the design and application of small molecules and chemical probes that can bind specifically to biomolecules, alter their chemical properties, visualize their location within cells, and modulate their function [10]. These tools are characterized by their rapid and often reversible effects, enabling the study of biological processes without the lengthy preparations required for genetic manipulations [10].

The field has evolved significantly in recent decades, driven by advancements in biochemical techniques, analytical instrumentation, and the ability to access and analyze large "big omics data" (including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) [11]. These developments have catalyzed the creation of sophisticated chemical tools that allow researchers to visualize biomolecules in live cells, regulate cell-signaling networks, identify therapeutic targets, and develop small-molecule drugs for a wide range of diseases [11]. The following sections provide a technical guide to the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these transformative tools.

Core Tool Classes and Their Mechanisms

Chemical tools for biological discovery can be broadly categorized based on their application and mechanism of action. The table below summarizes the primary classes of chemical tools, their key characteristics, and biological applications.

Table 1: Core Classes of Chemical Tools in Biological Discovery

| Tool Class | Key Characteristics | Primary Biological Applications | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Probes [11] | Enable visualization of biomolecules in live cells; often possess properties like high sensitivity and multiplexing capability. | Visualization of RNA dynamics, protein localization, and tracking of biological processes in real-time. | Bioluminescence tools, lanthanide-based probes, photosensitizers based on rhodamine scaffolds [11]. |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) [11] | Covalently bind to active enzymes, often targeting specific enzyme families; report on enzyme activity rather than mere abundance. | Profiling enzyme activity in complex proteomes, identifying active enzymes in disease states. | Probes for serine hydrolase family of enzymes [11]. |

| Pharmacological Perturbation Probes [11] | Includes inhibitors, activators, and other small molecules that modulate protein function. | Chemical interrogation of signaling pathways, target validation, and functional genomics. | Small-molecule kinase inhibitors, receptor agonists/antagonists [11]. |

| Targeted Protein Degraders [11] | Bifunctional molecules that recruit target proteins to cellular degradation machinery. | Inducing knockdown of protein levels rather than just inhibiting function; targeting previously "undruggable" proteins. | PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) [11]. |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids [10] | Synthetic amino acids with novel chemical functions; incorporated site-specifically into proteins. | Protein engineering, adding new functions to proteins (e.g., fluorescent labels, cross-linkers), studying protein structure/function. | Amino acids equipped with fluorescent labels or chemically reactive side chains [10]. |

Visualizing Biology: Imaging Tools

Chemical probes are indispensable for biological imaging, allowing researchers to observe molecular processes in live cells with high spatial and temporal resolution [11]. Key advancements in this area include:

- RNA Imaging Tools: Palmer and colleagues provide an overview of technologies for elucidating RNA dynamics, localization, and function in live mammalian cells, moving beyond static snapshots to real-time monitoring [11].

- Bioluminescence-Optogenetics Fusion: Love and Prescher summarize advances that merge bioluminescence with optogenetics, creating tools that not only sense but also enable control over biological processes [11].

- Lanthanide-Based Probes: Cho and Chen discuss probes that utilize lanthanide luminophores, which offer unusual sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities due to beneficial properties like long-lived photoluminescence and large Stokes shifts [11].

- Advanced Photosensitizers: Lavis et al. have developed photosensitizers based on a rhodamine scaffold for applications ranging from high-resolution imaging to the targeted destruction of proteins, demonstrating the dual utility of chemical tools for both observation and intervention [11].

Interrogating Function: Activity-Based and Perturbation Probes

Beyond visualization, chemical tools provide deep insight into protein function and serve as pharmacological modulators.

- Profiling Enzyme Families: Bogyo et al. focus on the application of activity-based probes (ABPs) for investigating the serine hydrolase family, allowing for functional profiling of enzyme activities in native systems [11].

- Studying Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Wang and Cole summarize small-molecule probes and protein chemistries that facilitate the characterization of writers, erasers, and readers of lysine post-translational modifications, which are crucial for regulating cellular signaling [11].

- Analyzing Endogenous Proteins: A critical criterion for probe development is the ability to analyze endogenous proteins under native conditions. Hamachi et al. review various chemical approaches for this, including ligand-directed chemistry for protein-selective labeling and proximity-dependent proteome labeling [11].

- Targeting Dynamic Proteins: Proteins that are highly dynamic have traditionally been difficult targets. Garlick and Mapp discuss screening approaches for identifying small molecules with affinity for these challenging proteins [11].

Controlling Biology: Targeted Protein Degradation

A paradigm shift in chemical biology has been the development of small molecules that induce the degradation of target proteins, rather than merely inhibiting their activity. Crews et al. present key advancements in the rapidly growing field of targeted protein degradation, particularly PROTAC (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera) technology [11]. PROTACs are bifunctional molecules that recruit a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to the target's ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. This approach can target proteins that lack defined active sites, making them "undruggable" by conventional small-molecule inhibitors.

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

The effective application of chemical tools requires robust and reproducible experimental protocols. The following section outlines general methodologies and points to key resources for detailed procedures.

General Workflow for Using Chemical Probes

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for applying chemical tools to probe a biological system, from target identification to data analysis.

A good protocol is essential for saving time and ensuring reproducible results in the laboratory [12]. The following resources are invaluable for finding detailed, peer-reviewed methodologies:

Table 2: Key Resources for Experimental Protocols in Chemical Biology

| Resource Name | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Nature Protocols [12] [13] | An online journal of laboratory protocols for bench researchers. | Protocols are presented in a detailed 'recipe' style, organized into logical categories. |

| Springer Nature Experiments [12] | Contains more than 75,000 molecular biology and biomedical peer-reviewed protocols. | Covers molecular techniques, microscopy, cell culture, spectroscopy, and antibodies. |

| Cold Spring Harbor Protocols [12] | Interdisciplinary journal providing research methods in cell, developmental and molecular biology. | A definitive source for established and cutting-edge methods. |

| Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE) [12] | A peer-reviewed journal publishing research in a video format. | Visual learning of complex techniques through video demonstrations. |

| Bio-Protocol [12] | A collection of peer-reviewed life science protocols. | Includes interactive Q&A sections for communication with authors. |

| Current Protocols (Wiley) [12] | A major laboratory methods series. | Includes basic, alternate, and support protocols with reagent preparation info. |

| Methods in Enzymology [12] | A classic laboratory methods book series. | Extensive, in-depth protocols and descriptions of biochemical techniques. |

| protocols.io [14] | A platform for sharing and collaborating on protocols. | Facilitates version control and private collaboration, improving reproducibility. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials commonly used in chemical biology experiments, particularly those involving chemical probes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Chemical Biology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) [11] | Covalently label the active site of enzymes (e.g., serine hydrolases) to report on activity states within a complex proteome. | Require a reactive group (warhead), a reporter tag (e.g., fluorophore, biotin), and a recognition element for specificity. |

| Photoaffinity Probes [11] | Enable the identification of protein interactors (e.g., ATP-interacting proteins) by forming covalent bonds upon UV irradiation. | Useful for capturing transient or weak interactions that are difficult to study with traditional methods. |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids [10] | Site-specifically incorporated into proteins to introduce novel chemical properties (e.g., photo-crosslinkers, fluorophores). | Require genetic code expansion with orthogonal tRNA/synthetase pairs. |

| PROTAC Molecules [11] [13] | Bifunctional degraders that recruit a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to target ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. | Consist of a target-binding ligand, an E3 ligase-binding ligand, and a linker. The linker length and composition are critical for efficiency. |

| Lanthanide Luminophores [11] | Used in sensitive imaging probes due to long-lived photoluminescence, allowing for time-gated detection to eliminate background autofluorescence. | Often require chelators for stability in aqueous solutions. |

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Discovery

Chemical tools have facilitated fundamental discoveries across diverse biological domains. The pathway diagram below illustrates how a chemical tool, such as a targeted protein degrader (PROTAC), exerts its effect and leads to a biological outcome.

Specific biological applications highlighted in recent literature include:

- Pancreatic Islet Function: Schultz and colleagues have applied small-molecule and genetically encoded tools to gain significant knowledge in pancreatic islet biology, which is critical for understanding diabetes [11].

- Thiopeptide Engineering: Suga et al. discuss thiopeptides, a class of natural products, focusing on their biological activities and the engineering approaches used to reprogram their structure and function for potential therapeutic applications [11].

- Bacterial Cell-Wall Biogenesis: Grimes et al. detail how chemical and biochemical tools have been employed to study bacterial cell-wall biogenesis, leading to the discovery of key components like cell-wall interacting proteins and flippases [11]. This research has important implications for developing new antibiotics.

The field of chemical biology is rapidly evolving, driven by improvements in the sensitivity of analytical instrumentation, accessibility to large omics datasets, and enhanced computational capabilities [11]. As new tools emerge, their application is expected to expand among a diverse group of researchers, from molecular biologists to clinicians [11]. The future will likely see increased integration of chemical tools with other technologies, such as single-cell analysis and spatial omics, providing an even more refined resolution of biological complexity.

In conclusion, the application of chemical tools to probe biological systems represents a cornerstone of modern life sciences. The core principles outlined in this guide—ranging from imaging and perturbation to targeted degradation—provide researchers with a powerful toolkit for deconvoluting complex biological processes. The continued development and thoughtful application of these tools, supported by robust and shareable protocols, will undoubtedly accelerate both basic biological discovery and the development of new therapeutics. As the field progresses, a commitment to interdisciplinary collaboration and diversity of thought will be essential for driving scientific innovation forward [11].

The evolution from traditional biochemistry to modern chemical biology represents a significant paradigm shift in the life sciences. Biochemistry is defined as the study of the chemical processes inherent in biological systems, focusing on understanding life processes at the molecular level, particularly the structure and function of cellular components such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids, and other biomolecules [6] [15]. In contrast, chemical biology involves the application of chemical techniques, tools, and principles—often using compounds produced through synthetic chemistry—to study and manipulate biological systems [3] [6] [15]. This transition reflects a movement from primarily observational science toward targeted engineering of biological systems.

The distinction between these fields, while sometimes subtle, is profound in its implications. As explained in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, biological chemistry (or biochemistry) seeks to understand life processes at the molecular level, while chemical biology applies chemical techniques and tools to the "study and manipulation of biological systems" [15]. This evolution has been driven by the recognition that explaining biological systems requires understanding both historical evolutionary causes and physical-chemical causes, integrating perspectives that were once largely separate [16].

Historical Schism: The Molecular Wars and Their Legacy

The separation between biochemical and evolutionary thinking has deep historical roots. In the 1950s and 1960s, a group of chemists recognized that molecular biology allowed studies of "the most basic aspects of the evolutionary process" [16]. They produced groundbreaking work on molecular phylogenetics, the molecular clock, ancestral protein reconstruction, and the importance of functionally neutral changes in evolution [16]. Unfortunately, this early integration attempt became collateral damage in the acrimonious battle between molecular and classical biologists [16].

Prominent evolutionary biologists like G. G. Simpson dismissed molecular biology as a "gaudy bandwagon ... manned by reductionists, traveling on biochemical and biophysical roads" [16]. This tension hardened into a cultural and institutional split as the fields competed for resources and legitimacy, with each group defining itself as asking incommensurable questions with different scientific aesthetics [16]. Biochemists and molecular biologists focused on dissecting underlying mechanisms in model systems, while evolutionary biologists analyzed how diversity of living forms in nature came to be [16]. At most institutions, biology departments split into separate entities, creating structural barriers to interaction between biochemists and evolutionists [16].

Ernst Mayr articulated this divide in 1961 by distinguishing between functional biology (considering proximate causes and asking "how" questions) and evolutionary biology (considering ultimate causes and asking "why" questions) [17]. This framework was used to argue for the continued relevance of organismal biology as it was losing ground to molecular approaches [17].

Table: Key Historical Divisions Between Disciplines

| Era | Primary Divide | Key Figures | Central Debate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s-1960s | Molecular vs. Organismal Biology | G.G. Simpson, Linus Pauling | Reductionism vs. Holism |

| 1960s-1970s | Functional vs. Evolutionary Biology | Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky | "How" vs. "Why" Questions |

| 1980s-1990s | Biochemistry vs. Molecular Biology | -- | Mechanism vs. Information |

| 2000s-Present | Biochemistry vs. Chemical Biology | -- | Observation vs. Manipulation |

The Paradigm Shift: Evolutionary Biochemistry as a Bridge

A crucial development in bridging these historical divides has been the emergence of evolutionary biochemistry, which aims to "dissect the physical mechanisms and evolutionary processes by which biological molecules diversified and to reveal how their physical architecture facilitates and constrains their evolution" [16]. This integration moves science toward a more complete understanding of why biological molecules have the properties they do [16].

The paradigm of evolutionary biochemistry combines evolutionary analysis with rigorous biophysical and biochemical studies, simultaneously asking "how things work" and "how they got to be that way" [16]. This approach provides unique insight into how evolution shapes the physical properties of biological molecules and how those properties shape evolutionary trajectories [16].

Key Methodological Advances in Evolutionary Biochemistry

Several experimental strategies have enabled rigorous work at the interface of evolution and the chemistry of biological molecules [16]:

Analysis of Evolutionary Trajectories: This involves reconstructing the historical trajectory that a protein or group of proteins took during evolution, using either population genetic analyses for recent evolution or ancestral protein reconstruction (APR) for ancient divergences [16]. APR uses phylogenetic techniques to reconstruct statistical approximations of ancestral proteins computationally, which are then physically synthesized and experimentally studied [16]. This allows researchers to characterize sequence substitutions that occurred during key evolutionary intervals and determine their effects on protein structure, function, and physical properties [16].

Directed Evolution: This approach drives a functional transition of interest in the laboratory and then studies the mechanisms of evolution [16]. A library of random variants of a protein of interest is generated and screened for a desired property, with selected variants iteratively re-mutagenized and subjected to selection to optimize the property [16]. This allows identification of causal mutations and their mechanisms by characterizing sequences and functions of intermediate states realized during protein evolution [16].

Charting Protein Sequence Space: This approach characterizes a portion of sequence space in detail using methods for characterizing large libraries of protein variants through deep sequencing [16]. It reveals the distribution of properties of interest in sequence space and illuminates the potential of various evolutionary forces to drive trajectories across this space [16].

Diagram: Directed Evolution Workflow for Protein Engineering

The Rise of Chemical Biology in Pharmaceutical Research

The pharmaceutical industry has played a crucial role in driving the adoption of chemical biology approaches. The last 25 years of the 20th century marked a pivotal period where companies developed highly potent compounds targeting specific biological mechanisms but faced significant challenges demonstrating clinical benefit [3]. This obstacle stimulated transformative changes leading to the emergence of translational physiology and precision medicine, aided by the development of the chemical biology platform [3].

The Chemical Biology Platform in Drug Development

The chemical biology platform represents an organizational approach to optimize drug target identification and validation while improving safety and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals [3]. It achieves this through emphasis on understanding underlying biological processes and leveraging knowledge gained from the action of similar molecules on these biological processes [3]. Unlike traditional trial-and-error methods, chemical biology focuses on selecting target families and incorporates systems biology approaches to understand how protein networks integrate [3].

The development of this platform occurred through three key steps [3]:

Bridging Chemistry and Pharmacology: Initially, pharmaceutical scientists primarily included chemists (who extracted, synthesized, and modified therapeutic agents) and pharmacologists (who used animal models and cellular systems to show potential therapeutic benefit and develop ADME profiles).

Introduction of Clinical Biology: This encouraged collaboration among preclinical physiologists, pharmacologists, and clinical pharmacologists, focusing on identifying human disease models and biomarkers that could more easily demonstrate drug effects before costly late-stage trials.

Formal Development of Chemical Biology Platforms: Introduced around 2000, this took advantage of genomics information, combinatorial chemistry, improvements in structural biology, high throughput screening, and various cellular assays that could be genetically manipulated.

Table: Evolution of Pharmaceutical Research Approaches

| Era | Dominant Approach | Key Technologies | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Physiology-Based Screening | Animal models, tissue assays | Low throughput, mechanistic uncertainty |

| 1980s-1990s | Mechanism-Based Target Approach | High-throughput screening, combinatorial chemistry | Limited structural biology, biomarker gaps |

| 2000s-Present | Chemical Biology Platform | Genomics, structural biology, multiparametric cellular assays | Integration complexity, data management |

Conceptual Frameworks: From Sequence Space to Predictive Modeling

A fundamental concept that has emerged in modern chemical biology is protein sequence space—a spatial representation of all possible amino acid sequences and the mutational connections between them [16]. In this conceptual framework, each sequence is a node connected by edges to all neighboring proteins that differ by just one amino acid [16]. This space becomes a genotype-phenotype space when each node is assigned information about functional or physical properties, creating a map of the total set of relations between sequence and those properties [16]. As proteins evolve, they follow trajectories along edges through this genotype-phenotype space [16].

This conceptual framework enables researchers to ask fundamentally new questions about evolutionary potential and constraints. Rather than仅仅 reconstructing what evolution did in the past, this strategy aims to reveal what it could do, given detailed knowledge of sequence space and fundamental understanding of evolutionary processes [16].

Modern Applications: Forecasting Viral Evolution

The power of integrating chemical biology with evolutionary principles is exemplified by recent work on forecasting viral evolution. Researchers have combined biophysics with artificial intelligence to identify high-risk viral variants rapidly by analyzing how mutations in proteins like SARS-CoV-2's spike protein change viral fitness and immune evasion [18].

This approach introduced a model that quantitatively linked biophysical features—such as binding affinity to human receptors and antibody evasion capability—to a variant's likelihood of surging in global populations [18]. By incorporating epistasis (where the effect of one mutation depends on another), the model overcame a key limitation of previous approaches [18]. The VIRAL (Viral Identification via Rapid Active Learning) framework combines this biophysical model with artificial intelligence to accelerate detection of high-risk variants, identifying those likely to enhance transmissibility and immune escape [18].

Diagram: Biophysical-AI Framework for Viral Forecasting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Methodologies in Chemical Biology

Modern chemical biology employs a sophisticated toolkit of methodologies that distinguish it from traditional biochemistry. These approaches emphasize the application of chemical techniques to manipulate and probe biological systems, rather than merely observe them [15].

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Chemical Biology

| Tool Category | Example Reagents/Techniques | Primary Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes | Serine hydrolase probes with biotin tags | Covalent modification and enrichment of enzyme family members | Target identification, enzyme family characterization, inhibitor screening [15] |

| Chemical Inducers of Protein Degradation | PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Target proteins for destruction by the proteasome | Probing protein function, alternative to RNAi, therapeutic development [15] |

| Unnatural Amino Acids | Orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs | Site-specific incorporation of novel amino acids | Protein engineering, introduction of fluorophores, post-translational modifications [15] |

| Chemical Inducers of Autophagy | Small molecule autophagy enhancers | Up-regulate autophagy or specific clearance of aggregated proteins | Neurodegenerative disease research, therapeutic development [15] |

| Synthetic Biological Tools | Small molecule transcriptional regulators | Control transcription in eukaryotic cells | Gene regulation studies, potential cancer therapeutics [15] |

Experimental Protocols in Chemical Biology

Protocol 1: Activity-Based Protein Profiling

This protocol relies on chemical probes consisting of three elements: a ligand for the enzyme or protein family under study, a reactive group for covalent modification of the protein, and a reporter tag (such as biotin for enrichment or a dye for visualization) [15]. The methodology allows investigators to identify targets of existing small molecules, characterize members of enzyme families en masse, or screen for inhibitors [15]. This approach is particularly valuable for characterizing the substantial fraction of predicted proteins in the human genome that remain of unknown function [15].

Protocol 2: Native Chemical Ligation for Modified Histones

This approach uses techniques of native chemical ligation and related synthetic methods to generate histones with unique post-translational modifications, such as lysine methylation and acetylation [15]. These synthetic methods enable researchers to produce uniquely and homogeneously modified histones, allowing investigation of chromatin structure and function in ways not possible with mixed populations of histones from biological sources [15]. These studies have identified specific lysine residues in histones that mediate internucleosome interactions and chromatin condensation [15].

Future Directions and Implications

The integration of chemical biology with evolutionary principles continues to advance, with implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. The field is increasingly characterized by interdisciplinary approaches that combine physical modeling with artificial intelligence, as exemplified by viral forecasting methods that can identify high-risk SARS-CoV-2 variants up to five times faster than conventional approaches while requiring less than 1% of experimental screening effort [18].

This paradigm shift from reactive tracking to proactive biological forecasting represents the culmination of the transition from traditional biochemistry to modern chemical biology [18]. Looking forward, researchers anticipate adapting and scaling these frameworks for broader use against challenges including other emerging viruses and rapidly evolving tumor cells [18].

The historical context from the "molecular wars" to the current integration of disciplines illustrates how the field has matured to recognize that both evolutionary and biochemical perspectives are essential for a complete understanding of biological systems [16] [17]. This hard-won integration now provides a robust foundation for addressing some of the most complex challenges in modern biology and medicine.

Bio-orthogonal chemistry and small molecule probes represent two pillars of modern chemical biology, providing powerful tools for investigating and manipulating biological systems with unprecedented precision. Bio-orthogonal chemistry refers to chemical reactions that can occur inside living systems without interfering with native biochemical processes, effectively creating a parallel reaction space within the complex cellular environment. These reactions are characterized by their selectivity, bio-compatibility, and ability to proceed rapidly under physiological conditions. The development of this concept, recognized by the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Morten Meldal, and K. Barry Sharpless, has fundamentally expanded our ability to study biomolecules in their native contexts [19].

Complementing these reactions, small molecule probes are chemically synthesized molecules designed to selectively detect, track, or modulate specific biological targets. These probes serve as molecular spies and manipulators, enabling researchers to visualize cellular components, monitor dynamic processes, and unravel complex signaling pathways. Small molecule probes possess several advantageous properties, including high spatial and temporal resolution, the ability to penetrate cellular membranes, and minimal perturbation to native systems. Their development has transformed pharmacological research by enabling precise interrogation of biological systems, selective modulation of protein function, tracking of cellular pathways, and uncovering of new therapeutic targets [20]. Together, these conceptual frameworks have created a versatile toolbox for bridging the chemical and biological worlds, advancing both basic research and therapeutic development.

Fundamental Principles of Bio-orthogonal Chemistry

Defining Characteristics and Reaction Requirements

Bio-orthogonal reactions must fulfill several stringent criteria to function effectively in biological environments. First and foremost, they must be highly selective, reacting only with their intended partner functional groups while remaining inert toward the vast array of biological functionalities present in cells, including water, nucleophiles, electrophiles, and redox-active species. This specificity ensures that labeling occurs only at the desired sites without generating background noise or toxic byproducts. Second, these reactions must proceed under physiological conditions—typically in aqueous solutions at neutral pH and temperatures between 4°C and 37°C. The reactions should not require extreme temperatures, organic solvents, or toxic catalysts that would compromise cellular viability.

Third, bio-orthogonal reactions should exhibit fast kinetics, as many biological applications require efficient labeling within experimentally practical timeframes, especially for tracking dynamic processes. Fourth, the reactions should generate stable, non-toxic products that do not disrupt normal cellular functions or accumulate to harmful levels. Finally, the functional groups involved must be non-perturbing when incorporated into biomolecules, meaning they should not alter the natural structure, function, or localization of the labeled molecule within the biological system. The successful integration of these characteristics has enabled researchers to perform selective chemistry in living cells, tissues, and even whole organisms, opening new frontiers for biological investigation [19].

Major Bio-orthogonal Reaction Classes

Several classes of bio-orthogonal reactions have been developed, each with unique characteristics, advantages, and optimal application contexts. The table below summarizes the key bio-orthogonal reactions used in chemical biology research:

Table 1: Major Bio-orthogonal Reaction Classes and Their Characteristics

| Reaction Name | Reaction Partners | Key Features | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC) | Azide, Alkyne | Regioselective, high yields, stable triazole products | Requires copper catalyst which can be cytotoxic | Protein labeling, nucleic acid tagging, material science |

| Strain-Promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC) | Azide, Cyclooctyne | No copper requirement, faster kinetics | Larger functional group size, potential background | Live-cell imaging, in vivo applications |

| Inverse Electron-Demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) | Tetrazine, Trans-cyclooctene (TCO) | Extremely fast kinetics, fluorogenic potential | Sensitivity of TCO to isomerization | Super-resolution imaging, rapid labeling |

| Staudinger Ligation | Azide, Phosphine | First developed bio-orthogonal reaction, biocompatible | Slower kinetics compared to newer methods | Historical significance, specific labeling applications |

The Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC) was a breakthrough as the premier click chemistry reaction, offering high regioselectivity, excellent yields, and minimal side products. However, the required copper catalyst exhibits cytotoxicity, limiting its use in living systems. This limitation spurred the development of Strain-Promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC), which utilizes ring strain in cyclooctyne derivatives to drive the reaction with azides without metal catalysts. More recently, the Inverse Electron-Demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) reaction between tetrazines and trans-cyclooctenes has gained prominence due to its exceptionally fast kinetics, often several orders of magnitude faster than other bio-orthogonal pairs, enabling rapid labeling in time-sensitive applications [19].

Small Molecule Probes: Design and Mechanisms

Structural Components and Functional Requirements

Small molecule probes are sophisticated chemical tools composed of several integrated structural components that collectively determine their function and effectiveness. The core scaffold, typically derived from natural products or synthetic libraries, provides the fundamental molecular framework that dictates the probe's physicochemical properties, including solubility, membrane permeability, and metabolic stability. Natural product-based probes are particularly valuable as they often possess inherent bioactivity, biocompatibility, and evolutionary optimization for interacting with biological systems [21]. The pharmacophore represents the critical three-dimensional arrangement of functional groups responsible for molecular recognition and binding to the intended biological target. This region determines the probe's specificity and affinity, enabling selective interaction with specific proteins, nucleic acids, or other biomolecules.

Many probes incorporate a reporting group or fluorophore that generates a detectable signal upon successful target engagement or in response to specific environmental changes. Common fluorophores include BODIPY, coumarins, rhodamines, and cyanine derivatives, each offering distinct spectral properties, quantum yields, and environmental sensitivities [19]. For probes designed to capture or isolate their targets, a handling tag such as biotin (for affinity purification) or an alkyne/azide (for subsequent bio-orthogonal labeling) may be incorporated. Finally, linker regions connect these various components, providing spatial separation and flexibility to minimize steric interference between functional elements while maintaining overall probe integrity.

Classification and Operational Mechanisms

Small molecule probes can be categorized based on their operational mechanisms and intended applications. Activity-based probes feature reactive functional groups that form covalent bonds with catalytically active enzymes, enabling detection and profiling of specific enzyme classes within complex proteomes. Affinity-based probes utilize high-affinity, non-covalent interactions to bind and report on target occupancy, often employing displacement strategies or conformational changes to generate signals. Metabolic probes are bioisosteres of natural metabolites that incorporate bio-orthogonal handles, allowing them to be processed by cellular machinery and incorporated into newly synthesized macromolecules for tracking metabolic pathways [22].

The signaling mechanisms of fluorescent small molecule probes are particularly diverse. Turn-on probes remain weakly fluorescent until undergoing a specific reaction or binding event that restores full fluorescence intensity, providing high signal-to-background ratios for sensitive detection. FRET-based probes rely on Förster Resonance Energy Transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores that undergo distance-dependent changes in fluorescence upon target engagement. Environmentally sensitive probes exhibit fluorescence changes in response to local properties such as pH, viscosity, or membrane potential, reporting on microenvironments within cellular compartments. Ratiometric probes emit at multiple wavelengths that shift in opposite directions upon target interaction, enabling quantitative measurements independent of probe concentration [19].

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Probe Design and Synthesis Workflow

The development of effective small molecule probes follows a systematic workflow that integrates computational design, chemical synthesis, and rigorous validation. The process begins with target identification and thorough analysis of the biological target's structure, function, and physiological context. For probe design based on natural products, this involves identifying the core bioactive scaffold and determining optimal sites for functionalization that will not compromise biological activity [21]. Modern approaches frequently employ structure-based design using X-ray crystallography, NMR, or homology models to understand ligand-target interactions at atomic resolution, guiding rational modifications to enhance specificity and potency.

The next phase involves computational screening of potential probe candidates through virtual libraries, assessing properties such as binding affinity, synthetic accessibility, and "drug-likeness" based on parameters like Lipinski's Rule of Five. For instance, structure-based virtual screening was successfully employed to identify novel and highly potent small molecule inhibitors targeting FLT3-ITD for acute myeloid leukemia treatment [20]. Following in silico design, chemical synthesis is performed, often employing modular strategies that facilitate late-stage diversification to create analog libraries. Critical to this process is the incorporation of bio-orthogonal handles (azides, alkynes) or reporting tags (fluorophores, biotin) at positions determined to be tolerant to modification. The synthetic route must balance efficiency with flexibility, allowing for iterative optimization based on biological testing results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Probe Development and Application

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-orthogonal Reaction Pairs | Azides, Cyclooctynes, Tetrazines, TCO | Selective molecular conjugation in biological environments |

| Fluorophores | BODIPY, Coumarins, Rhodamines, Cyanine dyes | Signal generation for imaging and detection |

| Natural Product Scaffolds | Plant-derived metabolites, Microbial natural products | Providing bioactive foundations for probe design |

| Affinity Tags | Biotin, His-tags | Target capture and purification |

| Enzyme Targets | Kinases, Proteases, Phosphatases | Validation of probe specificity and functionality |

| Cell Line Models | Cancer lines, Primary cells, Stem cells | Biological testing in relevant cellular contexts |

Target Identification and Validation Protocols

Identifying the cellular targets of small molecule probes represents a critical challenge in chemical biology, particularly for probes derived from natural products with known biological activities but unknown mechanisms of action. Affinity-based protein profiling (ABPP) provides a powerful methodology for target identification, wherein the bioactive probe is modified with a handling tag (typically biotin or a fluorescent dye) and incubated with cell lysates or living cells. The probe binds to its protein targets, which are then captured using streptavidin beads (for biotinylated probes) or visualized directly (for fluorescent probes). Following washing to remove non-specific interactions, bound proteins are eluted and identified through mass spectrometric analysis [21].

For validation of target engagement, several complementary approaches are employed. Cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) monitor the thermal stabilization of target proteins upon probe binding, providing evidence of direct interactions in cellular environments. Genetic validation using RNA interference or CRISPR-Cas9 to knock down or knock out putative target genes can establish whether these genes are necessary for probe activity. Biochemical validation through recombinant protein production and in vitro binding assays (e.g., surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry) provides quantitative measurements of binding affinity and kinetics. Finally, phenocopy experiments in which the biological effects of the probe are recapitulated by genetic manipulation of the putative target provide compelling evidence for specific target engagement [20] [21].

Bio-orthogonal Labeling and Imaging Workflows

The application of bio-orthogonal chemistry with small molecule probes follows well-established workflows that can be adapted for various experimental goals. For metabolic labeling and tracking, cells or organisms are first incubated with a metabolite analog bearing a bio-orthogonal functional group (e.g., an azido-modified sugar, amino acid, or lipid). This precursor is incorporated by endogenous biosynthetic machinery into newly synthesized macromolecules. After a suitable incorporation period, the cells are exposed to a complementary detection reagent (e.g., a cyclooctyne-fluorophore conjugate) that undergoes bio-orthogonal reaction with the metabolically incorporated tag, enabling visualization of the labeled biomolecules [22].

The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for metabolic labeling using bio-orthogonal chemistry:

For protein-specific labeling, two main strategies are employed: direct tagging and ligand-directed targeting. In direct tagging, genetic engineering introduces a protein tag (e.g., SNAP-tag, HaloTag, or a simple tetracysteine motif) that reacts specifically with complementary small molecule probes. Alternatively, ligand-directed targeting utilizes high-affinity ligands for endogenous proteins that are conjugated to bio-orthogonal handles, enabling selective labeling without genetic manipulation. The labeling efficiency is optimized by controlling factors such as reagent concentration, incubation time, temperature, and catalyst concentration (if applicable). Following the bio-orthogonal reaction, extensive washing removes unreacted detection reagents before imaging or analysis to minimize background signal [19].

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Discovery

Proteome Exploration and Target Identification

Small molecule probes have revolutionized proteome exploration by enabling systematic analysis of protein function, localization, and interaction networks on a global scale. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) utilizes probes with reactive electrophiles that target mechanistically related enzyme families based on shared active site features, allowing simultaneous assessment of multiple enzymes' functional states within complex proteomes. This approach has been particularly valuable for mapping enzymatic activities dysregulated in disease states, identifying potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. For example, probes targeting serine hydrolases, cysteine proteases, and protein kinases have revealed enzyme activities associated with cancer progression, infectious diseases, and metabolic disorders [20].

Recent innovations have expanded these capabilities through integration with advanced screening technologies. One notable contribution introduces "an elegant strategy to systematically study protein-small molecule interactions by integrating pooled protein tagging with ligandable domains," offering a scalable way to profile the ligandability of the proteome and significantly accelerate probe development pipelines [20]. This and similar approaches facilitate functional annotation of understudied proteins, a critical challenge in the post-genomic era. The resulting datasets provide insights into pharmacologically accessible targets and guide the development of selective inhibitors for therapeutic applications.

Imaging and Diagnostic Applications

The fusion of bio-orthogonal chemistry with advanced imaging modalities has created powerful platforms for visualizing biomolecules in living systems with high spatiotemporal resolution. Fluorescent probes based on bio-orthogonal reactions enable specific labeling of cellular components without the limitations of genetic encoding, particularly valuable for tracking non-genetically encoded biomolecules such as glycans, lipids, and secondary metabolites. In plant biology, for instance, these tools "provide an alternative to genetic approaches and allow the study of dynamic processes in species or organs that are not easily accessible" [22]. Through metabolic incorporation of small-molecule probes into specific molecular scaffolds such as sugars, monolignols, amino acids, and lipids, researchers can follow events like glycosylation, lignification, lipid turnover, or protein synthesis in living plant tissues with precision.

In biomedical applications, bio-orthogonal probes have enabled significant advances in molecular imaging and diagnostics. The development of radiolabeled probes extends these capabilities to clinical imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET). For example, the "radiosynthesis and in-vitro identification of a molecular probe 131I-FAPI targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts" demonstrates how small molecule probes can bridge therapeutic and diagnostic objectives [20]. Such approaches allow non-invasive detection of disease-associated biomarkers, monitoring of treatment responses, and visualization of drug distribution in vivo. The high specificity of bio-orthogonal reactions minimizes off-target labeling, enhancing signal-to-noise ratios essential for sensitive detection of low-abundance targets in complex biological environments.

Therapeutic Development and Chemical Genetics

Small molecule probes serve as critical tools throughout the therapeutic development pipeline, from target validation to lead optimization. In chemical genetics, probes with well-defined mechanisms of action are used to mimic genetic perturbations, enabling functional dissection of signaling pathways and biological processes that may be difficult to study using traditional genetic approaches. This strategy was effectively employed in discovering "novel PARP1/NRP1 dual-targeting inhibitors with strong antitumor potency," introducing a multitargeted approach to cancer therapy that could improve efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms associated with monotherapy [20].

The emergence of targeted protein degradation technologies exemplifies the expanding therapeutic applications of small molecule probes. Molecular glue degraders, such as "a small-molecule VHL molecular glue degrader for cysteine dioxygenase 1," represent a powerful strategy to target previously intractable proteins by inducing proximity between the target and E3 ubiquitin ligase machinery, leading to proteasomal degradation [23]. Similarly, the development of "methylarginine targeting chimeras (MrTAC) for lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins" demonstrates how small molecules can be designed to direct specific proteins to alternative degradation pathways [23]. These approaches expand the druggable proteome beyond traditional enzyme and receptor targets to include scaffolding proteins, regulatory factors, and other non-enzymatic components previously considered undruggable.

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Technical Limitations and Optimization Strategies

Despite significant advances, several technical challenges persist in the development and application of bio-orthogonal chemistry and small molecule probes. Probe specificity remains a concern, particularly for probes targeting protein families with conserved structural features, where off-target interactions can complicate data interpretation. Strategies to enhance specificity include structure-based design to exploit subtle differences in target binding sites, as demonstrated in the development of cholesterol-targeting Wnt-β-catenin signaling inhibitors that selectively restrict colorectal tumor growth while sparing normal intestinal epithelium [23]. Cellular permeability represents another hurdle, especially for probes with extensive conjugation systems or polar functional groups. Structural modifications to improve membrane crossing while maintaining target engagement include strategic incorporation of hydrophobic moieties, reduction of hydrogen bond donors, and formulation with delivery enhancers.

The kinetics of bio-orthogonal reactions in complex biological environments sometimes limit application efficiency, particularly for reactions with slower rate constants. Continuing development of novel bio-orthogonal pairs with enhanced kinetics, such as the increasingly popular IEDDA reaction between tetrazines and trans-cyclooctenes, addresses this limitation. Additionally, signal amplification strategies may be necessary for detecting low-abundance targets, including enzyme-based amplification systems or multi-step labeling protocols that deposit multiple fluorophores at each tagging site. For in vivo applications, probe pharmacokinetics including bioavailability, tissue distribution, and metabolic stability require careful optimization through iterative design and testing, often employing prodrug strategies or formulation approaches to enhance desired properties [20] [19].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of bio-orthogonal chemistry and small molecule probes continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Multimodal probes that combine complementary detection modalities (e.g., fluorescence and radioactivity) enable correlative imaging across scales, bridging microscopic cellular visualization with whole-organism distribution studies. Conditionally activated probes that remain silent until encountering specific biochemical cues (e.g., enzyme activities, pH changes, or reactive oxygen species) provide enhanced spatial precision for imaging in complex tissues. The development of "a fluorescent probe for the efficient discrimination of Cys, Hcy and GSH based on different cascade reactions" exemplifies this approach, enabling selective detection of biologically similar thiol-containing metabolites [19].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches is accelerating probe design and optimization, with computational models increasingly predicting synthetic accessibility, target binding, and ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) properties prior to synthesis. As noted in recent screening efforts, "the docking of a 1.7 billion- versus a 99 million-molecule virtual library against β-lactamase revealed that the larger-sized library produced improved hit rates and potency along with an increased number of scaffolds" [23], highlighting the value of expansive in silico screening resources. Finally, the application of these technologies in interdisciplinary contexts is expanding their impact beyond traditional biological research, with chemical reporters entering "collaborations between science and the arts" and "converting molecular-level information into visual and sensory formats" that open new perspectives for research, education, and communication across scientific and creative disciplines [22].

The continued convergence of chemical biology with structural pharmacology, systems biology, and computational chemistry promises to address current limitations and unlock new applications. As these fields advance, bio-orthogonal chemistry and small molecule probes will remain essential tools for elucidating biological mechanisms, diagnosing diseases, and developing targeted therapeutics with increasing precision and efficacy.

Chemical biology represents a powerful interdisciplinary field where strategies, tools, and techniques developed through chemical research are applied to investigate biological phenomena and problems [24]. This discipline has moved beyond mere rebranding of established fields like bioorganic chemistry and molecular biology, emerging as a distinct area where chemists strive to move into biology and biologists aim to employ chemistry in their research [24]. The fundamental premise of chemical biology lies in using well-defined chemical interventions to precisely perturb, monitor, and manipulate cellular and molecular processes, thereby elucidating function and mechanism in a manner that often complements genetic approaches [25]. The tools in the chemical biologist's toolbox—ranging from small molecule modulators and activity-based probes to synthetic molecules and genetic circuits—provide unprecedented temporal control, reversibility, and tunability that enable dissection of dynamic biological processes with high precision.

The youth of chemical biology as a formal scientific discipline is reflected in its recent establishment in university education programs, with many courses and international programs developed only in the past decade [24]. This rapid institutional recognition parallels the field's methodological expansion, driven by two complementary trends: the development of increasingly sophisticated tools for complex biological questions and the implementation of streamlined, accessible methods for widespread application [25]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the core components of the chemical biologist's toolbox, framed within the broader context of basic principles and introductory research in chemical biology, with particular emphasis on their applications for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Small Molecule Probes and Modulators

Defining High-Quality Chemical Probes

Small-molecule chemical probes represent among the most important tools for studying protein function in cells and organisms [26]. These are highly characterized small molecules that modulate the biological function of specific proteins through binding to orthosteric or allosteric pockets, and they can be used across biochemical assays, cellular systems, and in vivo settings [26]. The historical use of weak and non-selective small molecules has generated an abundance of erroneous conclusions in scientific literature, prompting the chemical biology community to establish minimal criteria or 'fitness factors' for high-quality chemical probes [26].

According to consensus criteria, chemical probes must demonstrate potency (IC50 or Kd < 100 nM in biochemical assays, EC50 < 1 μM in cellular assays) and selectivity (selectivity >30-fold within the protein target family, with extensive profiling of off-targets outside the primary target family) [26]. Additionally, chemical probes must not be highly reactive promiscuous molecules, and researchers should avoid nonspecific electrophiles, redox cyclers, chelators, and colloidal aggregators that modulate biological targets promiscuously through undesirable mechanisms of action [26]. Best practices also recommend using structurally distinct high-quality chemical probes targeting the same protein whenever possible, alongside inactive analogs (presumed to bind only the off-targets of the corresponding active small molecule) to support the association between on-target engagement and observed phenotypes [26].

Table 1: Quality Criteria for High-Quality Chemical Probes

| Parameter | Minimum Standard | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | IC50 or Kd < 100 nM (biochemical); EC50 < 1 μM (cellular) | Cellular potency should demonstrate target engagement in physiologically relevant environments |

| Selectivity | >30-fold within protein target family | Extensive profiling against off-targets both within and outside primary target family |

| Solubility/Stability | Suitable for intended experimental context | Compound should remain stable under experimental conditions |

| On-target Engagement | Demonstrated in cellular contexts | Evidence of target modulation in live cells |

| Inactive Control | Structurally similar but inactive analog | Should be screened for potential off-target profiles |

Advanced Modalities: Protein Degraders and PPI Inhibitors

Beyond conventional inhibitors, agonists, and antagonists, recent years have witnessed the emergence of innovative probe modalities, particularly small molecules inducing target protein degradation [26]. PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues represent two classes of protein degraders that have attracted significant interest [26]. These bifunctional molecules recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases in proximity to specific target proteins, leading to ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation [26]. Unlike gene knockout approaches, PROTACs and molecular glues produce concentration-dependent target degradation within hours, providing greater temporal control when investigating protein function, including scaffold-dependent activities [26].

Protein degraders provide a route to target proteins with less well-defined small-molecule-binding clefts, many previously considered 'undruggable' by conventional means [26]. This expansion of the targetable proteome is particularly significant for drug development, with at least 15 bifunctional degraders in clinical trials by the end of 2021 [26]. Similarly, protein-protein interaction (PPI) inhibitors have emerged as valuable tools for targeting proteins that function primarily through macromolecular interactions rather than enzymatic activity [25]. Although PPIs mediated by large surface areas were historically considered difficult to target, research has revealed that molecular interactions across these surfaces often occur at specific regions termed 'hot spots,' enabling design of chemical probes that interfere with PPIs spanning relatively large surface areas [26].

Diagram 1: PROTAC Mechanism of Action - PROTAC molecules simultaneously bind E3 ubiquitin ligase and target protein, leading to ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the target.

Research Reagent Solutions: Small Molecule Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Inhibitors | Actinomycin D, Cycloheximide, MG132, Brefeldin A | Block specific cellular processes (transcription, translation, proteasome function, Golgi transport) |

| Protein Degraders | PROTACs, Molecular Glues | Induce targeted protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system |

| PPI Inhibitors | Nutlin (MDM2-p53 inhibitor) | Disrupt specific protein-protein interactions |

| Activity-Based Probes | Fluorophosphonate- and vinyl sulfone-based probes | Covalently label active enzymes for detection and quantification |

| Bio-orthogonal Reagents | Azide- and alkyne-containing compounds, Tetrazines | Enable specific labeling of biomolecules in living systems via click chemistry |

Activity-Based Probes and Detection Technologies

Principles and Design of Activity-Based Probes

Activity-based probes (ABPs) represent a specialized class of chemical tools designed to monitor enzymatic activity within its native cellular context [25]. Unlike conventional probes that simply bind their targets, ABPs are engineered to bind covalently and specifically to the active site of an enzyme or enzyme class [25]. Their design typically incorporates three key elements: (1) a reactive moiety (warhead) that covalently modifies the active site, (2) a recognition element that provides specificity for the target enzyme(s), and (3) a reporter tag (e.g., fluorophore, biotin) for detection and purification [25].

This sophisticated design enables ABPs to report specifically on the functional state of enzymes, distinguishing active enzymes from their inactive zymogen or inhibitor-bound forms. This capability is particularly valuable for studying enzymatic processes in complex biological systems where protein abundance may not correlate with activity. ABPs have been developed for numerous enzyme classes, including serine and cysteine hydrolases, proteasomes, glycosidases, and kinases [24] [25]. The development and application of ABPs for serine and cysteine hydrolases, proteasomes, and glycosidases represents a core topic in modern chemical biology education [24].

Experimental Workflow for Activity-Based Protein Profiling

The standard workflow for activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) begins with preparation of the biological sample (cell lysate, intact cells, or tissue), which is incubated with the activity-based probe to allow specific labeling of active enzymes [25]. After appropriate labeling time, reactions are stopped, and samples are processed based on the detection method employed. For fluorescent probes, proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by in-gel fluorescence scanning [25]. For biotinylated probes, labeled proteins are captured using streptavidin beads, separated by SDS-PAGE, and detected by Western blotting with streptavidin-HRP, or alternatively identified by mass spectrometry after tryptic digestion [25].