BlaR1 Sensor Inhibition: A Novel Strategy to Resensitize MRSA to β-Lactam Antibiotics

The global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance demands innovative therapeutic strategies, particularly against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

BlaR1 Sensor Inhibition: A Novel Strategy to Resensitize MRSA to β-Lactam Antibiotics

Abstract

The global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance demands innovative therapeutic strategies, particularly against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). This article comprehensively reviews the groundbreaking approach of inhibiting the BlaR1 sensor protein to disarm bacterial resistance and restore the efficacy of conventional β-lactam antibiotics. We explore the foundational molecular biology of BlaR1-mediated signal transduction, analyze recent breakthroughs in inhibitor design and screening, address key challenges in drug optimization and delivery, and validate this strategy against other emerging therapies. Synthesizing current research and pre-clinical data, we provide a critical assessment for researchers and drug development professionals, highlighting BlaR1 inhibition as a promising pathway for developing effective antibiotic adjuvants to combat multidrug-resistant infections.

The BlaR1 Signaling Pathway: Decoding MRSA's β-Lactam Defense System

The Role of BlaR1 in Staphylococcal Resistance and the bla Operon

The bla operon is a key genetic determinant conferring inducible resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains. This operon encodes three primary proteins: BlaR1, the sensor-signal transducer; BlaI, the gene repressor; and BlaZ, the PC1 β-lactamase [1]. In the absence of β-lactam antibiotics, BlaI represses the transcription of these genes by binding to operator regions within the operon. Upon exposure to β-lactams, BlaR1 senses the antibiotic and initiates a signal transduction cascade that culminates in the proteolytic degradation of BlaI, derepressing the operon and enabling the expression of resistance determinants [1] [2]. This sophisticated regulatory system allows MRSA to activate defense mechanisms only when challenged, conserving cellular resources. The following application note details the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and key reagents essential for investigating this system, with a particular focus on BlaR1 as a therapeutic target for resensitizing MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics.

Molecular Mechanism of BlaR1 Signaling

Signal Initiation: β-Lactam Sensing and Acylation

The resistance cascade begins when β-lactam antibiotics bind to the extracellular sensor domain of BlaR1. This domain shares structural homology with class D β-lactamases. The antibiotic acylates an active-site serine residue within this sensor domain, forming a stable acyl-enzyme complex [3] [4]. This acylation event is irreversible and enjoys a longevity that often exceeds the bacterial doubling time, meaning a single modification event can sustain the signal for an entire generation [1].

Signal Transduction: Conformational Activation

Acylation of the sensor domain triggers a series of conformational changes that propagate across the bacterial membrane. Recent cryo-EM structures of full-length BlaR1 reveal it forms a domain-swapped dimer [3]. The acylation event is proposed to competitively displace an extracellular loop from the sensor domain's active site, initiating a structural shift. This shift is transmitted through the transmembrane regions, ultimately affecting the conformation of the cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain [3] [4]. This N-terminal metalloprotease domain contains the characteristic gluzincin motif (HExxH) and is embedded within the membrane, forming a hydrophilic chamber [3] [4].

Proteolytic Activation and Gene Derepression

The conformational change in the cytoplasmic domain activates its proteolytic function. Prior to activation, this domain undergoes autocleavage in cis between residues Ser283 and Phe284, an event that may contribute to its regulation [3]. The activated BlaR1 protease then directly cleaves the BlaI repressor [3]. BlaI is a DNA-binding protein that exists as a mixture of monomers and dimers at physiological concentrations and binds operator DNA primarily as a monomer [2]. Its cleavage releases the repression of the bla operon, allowing rapid transcription of blaZ (β-lactamase), blaR1, and blaI itself. The BlaZ β-lactamase then hydrolyzes the β-lactam antibiotic, conferring resistance [1].

Table 1: Key Molecular Events in BlaR1-Mediated Induction of Resistance

| Molecular Event | Key Participants | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| β-Lactam Sensing | BlaR1 sensor domain, β-lactam antibiotic | Irreversible acylation of BlaR1 sensor |

| Signal Transduction | Transmembrane helices, BlaR1 dimer interface | Conformational change in cytoplasmic protease domain |

| Protease Activation | Zinc metalloprotease domain, autocleavage loop | Activation of proteolytic activity (autocleavage & BlaI cleavage) |

| Repressor Inactivation | BlaI repressor protein | Proteolytic degradation of BlaI |

| Gene Derepression | bla operator sequence (R1 & Z dyads) | Transcription of blaZ, blaR1, and blaI |

Phosphorylation as a Regulatory Layer

Beyond proteolytic activation, phosphorylation plays a critical role in BlaR1 signaling. Upon exposure to β-lactams, the cytoplasmic domain of BlaR1 is phosphorylated on at least one serine and one tyrosine residue [5]. Inhibition of this phosphorylation by synthetic kinase inhibitors abrogates the induction of resistance and can resensitize MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics, demonstrating that phosphorylation is essential for manifesting resistance [5].

System Reset and Recovery

Once the antibiotic challenge is removed, the system must reset. BlaR1 undergoes regulated fragmentation at specific sites in both the cytoplasmic and sensor domains [1]. This fragmentation, including the shedding of the acylated sensor domain into the medium, is proposed to be a turnover mechanism that allows the bacterium to recover from the induced state and return to a baseline level of vigilance [1] [6].

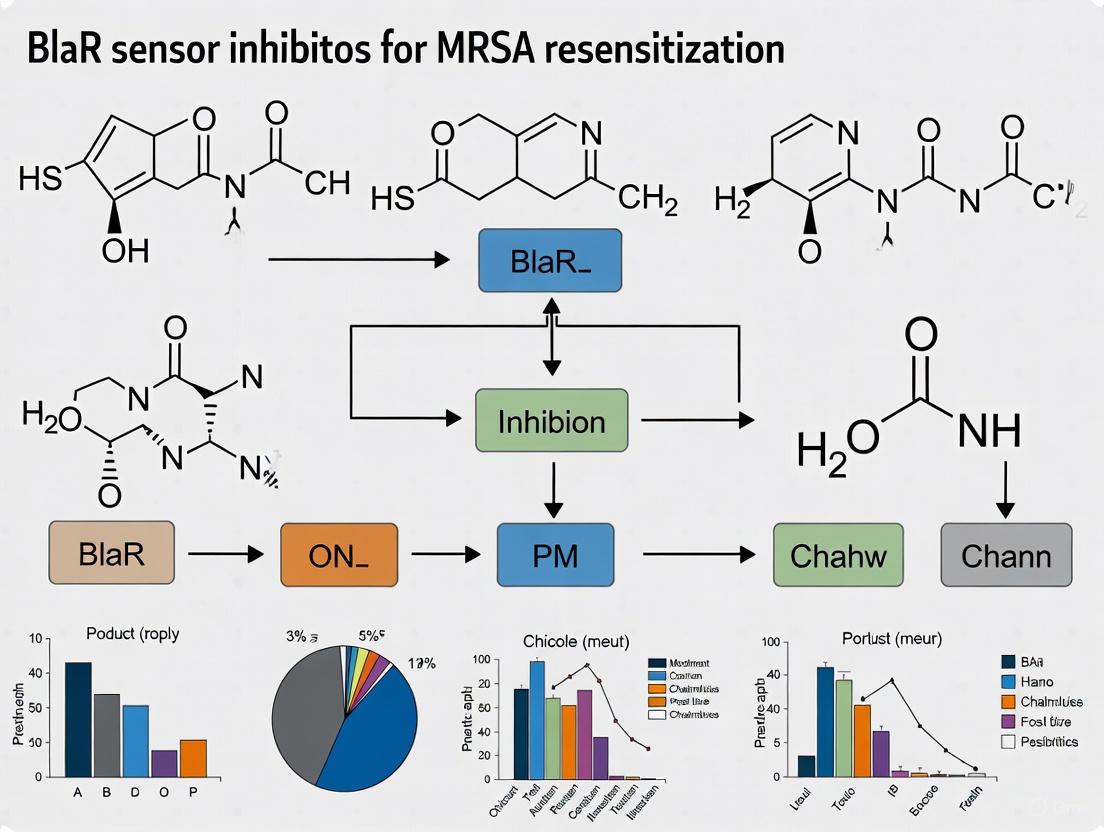

The diagram below summarizes the core signaling pathway of the BlaR1/BlaI system.

Quantitative Data on Key System Components

Understanding the biochemistry of the BlaR1/BlaI system requires knowledge of the molecular concentrations and binding affinities that govern its function.

Table 2: Quantitative Physicochemical Parameters of the BlaR1/BlaI System

| Component / Interaction | Measured Parameter | Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BlaI Repressor | In vivo concentration | 1.3 - 6.4 µM | S. aureus cells, exponential phase [2] |

| BlaI Monomer-Dimer Equilibrium | Dissociation Constant (Kd) | 1.61 ± 0.02 µM | Sedimentation equilibrium [2] |

| BlaI Binding to Full bla Operator | Monomer Kd (Kd1) | 0.45 ± 0.07 µM | Fluorescence anisotropy [2] |

| BlaI Binding to Z Dyad | Monomer Kd (Kd1) | 0.05 ± 0.04 µM | Fluorescence anisotropy [2] |

| BlaR1 Fragmentation | Timeframe for observation | Within 3 hours | Upon antibiotic exposure [1] |

| Kinase Inhibitor Efficacy | MIC reduction for oxacillin | 4 to 512-fold | In MRSA252, NRS123, NRS70 strains [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides standardized protocols for key experiments investigating the BlaR1/BlaI system.

Protocol: Monitoring BlaR1 and BlaI Dynamics During Antibiotic Induction

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to track the fate of BlaR1, BlaI, and β-lactamase in S. aureus upon antibiotic exposure [1].

Application: Used to study the time-dependent proteolytic events (BlaI degradation, BlaR1 fragmentation) and β-lactamase production that constitute the induction response.

Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: MRSA strains (e.g., NRS128, NRS123, NRS70, MRSA252).

- Antibiotics: β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin G, Ampicillin, Oxacillin, CBAP) prepared at sub-MIC concentrations.

- Growth Medium: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth.

- Lysis Buffer: 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaHCO₃, 1x EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM MgCl₂, DNase I (15 µg/ml), RNase A (15 µg/ml), lysostaphin (200 µg/ml).

- Antibodies: Rabbit polyclonal anti-BlaRS (recognizes BlaR1) and anti-BlaI.

Procedure:

- Culture and Induction: Grow 250 mL of S. aureus culture in LB at 37°C with shaking until the optical density at 625 nm (OD₆₂₅) reaches ~0.8 (exponential phase). Divide the culture into 30 mL aliquots. To each aliquot, add a sub-MIC concentration of a β-lactam antibiotic (e.g., 3.2x below MIC for penicillin, 6.4x below for CBAP). Maintain one aliquot as an uninduced control.

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect 5 mL samples from each culture at critical time points post-induction (e.g., 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h). Centrifuge samples at 3,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C to separate cell pellets from culture supernatants.

- Sample Preparation:

- Cell Pellet (Whole-Cell Extract): Resuspend pellets in Lysis Buffer and incubate at 37°C for 30 min. Quantify total protein concentration using an assay such as the BCA assay. Load 60-80 µg of total protein per lane for SDS-PAGE and subsequent Western blotting.

- Culture Supernatant: Assay immediately for extracellular β-lactamase activity using a nitrocefin hydrolysis assay or similar method. Supernatants can also be analyzed for the presence of the shed BlaR1 sensor domain.

- Analysis:

- Perform Western blot analysis on whole-cell extracts using anti-BlaI and anti-BlaR1 antibodies to monitor BlaI degradation and BlaR1 fragmentation over time.

- Measure β-lactamase activity in the supernatants spectrophotometrically to correlate repressor cleavage with resistance protein production.

Protocol: Assessing BlaR1 Phosphorylation and Inhibitor Effects

This protocol outlines the procedure for detecting BlaR1 phosphorylation and testing the efficacy of kinase inhibitors [5].

Application: Essential for validating the role of phosphorylation in signal transduction and for screening potential adjuvant compounds that resensitize MRSA to β-lactams.

Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: S. aureus strains (e.g., NRS128, MRSA252).

- Inducer: CBAP (10 µg/mL).

- Kinase Inhibitors: Lead compounds (e.g., Inhibitors 10, 11, 12 from [5]).

- Lysis Buffer: (As in Protocol 4.1, supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors).

- Antibodies: Anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-phosphoserine, and anti-BlaR1.

Procedure:

- Culture and Treatment: Grow S. aureus cultures to the exponential phase. Treat cultures with:

- No additions (negative control).

- CBAP alone (positive control for induction).

- CBAP + varying concentrations of kinase inhibitor (e.g., 0.7 µg/mL, 7 µg/mL).

- Whole-Cell Extract Preparation: Harvest cells after a defined induction period (e.g., 1 h). Lyse cells using a suitable lysis buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors.

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane.

- Probe the membrane with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-phosphoserine antibodies to detect phosphorylation of BlaR1.

- Strip and re-probe the membrane with anti-BlaR1 antibody to confirm equal loading.

- Functional Validation (MIC Assay):

- Determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of oxacillin against the MRSA strain using the broth microdilution method in the presence and absence of the kinase inhibitor.

- A significant reduction (e.g., 4-fold or more) in the MIC of oxacillin in the presence of a non-bactericidal inhibitor confirms the functional blockade of the resistance induction pathway.

The molecular architecture of BlaR1 and its activation mechanism are illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Targeting the BlaR1/BlaI system for mechanistic study or drug discovery requires a specific set of reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating BlaR1/BlaI Function

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized β-Lactam Inducers | Potent induction of the bla system for experimental studies. | CBAP: A potent penicillin-based inducer often used at 6.4x below MIC to robustly activate the system without immediate bacterial killing [1] [5]. |

| BlaR1 Phosphorylation Inhibitors | Tool compounds to probe the role of phosphorylation in resistance. | Imidazole-based inhibitors: e.g., Inhibitors 10, 11, 12 from [5]. These synthetic compounds inhibit BlaR1 tyrosine phosphorylation and resensitize MRSA to oxacillin. |

| Polyclonal Antibodies | Detection of BlaR1 and BlaI proteins and their post-translational modifications. | Anti-BlaRS: Detects BlaR1 protein and its fragments. Anti-BlaI: Monitors repressor degradation. Anti-phosphotyrosine/ Anti-phosphoserine: Confirm BlaR1 phosphorylation status [1] [5]. |

| Defined Operator DNA Sequences | Study of BlaI-DNA binding thermodynamics and kinetics. | Double-stranded DNA oligos: Corresponding to the R1 dyad, Z dyad, and full-length bla operator. Often 5'-labeled with fluorescein for fluorescence anisotropy binding assays [2]. |

| Recombinant BlaI Protein | In vitro studies of dimerization and DNA binding. | Purified to homogeneity from E. coli. Used in sedimentation equilibrium experiments to determine monomer-dimer Kd and in fluorescence anisotropy to determine DNA-binding affinities [2] [7]. |

Concluding Remarks and Research Outlook

The BlaR1/BlaI system represents a master regulatory switch for β-lactam resistance in MRSA. Its dual-layer activation mechanism, involving proteolytic cleavage and essential phosphorylation, offers multiple potential points for therapeutic intervention. The experimental protocols and reagents detailed herein provide a foundation for probing this system. The most promising research direction involves developing adjuvant therapies that combine existing β-lactams with BlaR1 kinase inhibitors or allosteric blockers of signal transduction. Such strategies aim to block the induction of resistance at its source, effectively resensitizing MRSA to conventional antibiotics and resurrecting the utility of this critical drug class. Continued structural elucidation of full-length BlaR1 in different states, coupled with high-throughput screening for potent and specific inhibitors, will be vital for translating this knowledge into novel treatment options.

The escalating global health threat of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is intrinsically linked to the activity of BlaR1, an integral membrane protein that acts as the primary sensor and inducer of β-lactam antibiotic resistance [8] [9]. This application note details the molecular architecture and functional mechanisms of BlaR1, providing researchers with a structured framework of its domains, signaling pathways, and key experimental methodologies. A comprehensive understanding of BlaR1's structure, from its extracellular sensor to its cytoplasmic protease domain, is paramount for the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at resensitizing MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. The protocols and data summarized herein are designed to support ongoing drug discovery efforts targeting the inhibition of this critical resistance pathway.

Molecular Architecture and Functional Domains of BlaR1

BlaR1 is a multidomain transmembrane protein that orchestrates the inducible β-lactam resistance response in S. aureus. Its functional domains work in concert to detect the antibiotic threat and initiate a cytoplasmic signaling cascade that culminates in the expression of resistance determinants [8] [10] [11].

Table 1: Functional Domains of BlaR1

| Domain | Location | Key Structural Features | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Sensor Domain (BlaRS) | Extracellular, C-terminal | Structurally related to class D β-lactamases; contains a conserved active-site serine (Ser389) [8] | Covalently binds and acylates β-lactam antibiotics via Ser389 [8] |

| Transmembrane Domain | Plasma Membrane | Comprises four transmembrane α-helices (TM1-TM4); connects the sensor to the cytoplasmic domain [8] [10] | Anchors the protein and transduces the acylation signal across the membrane [8] |

| Cytoplasmic Zinc Metalloprotease Domain | Cytoplasmic, N-terminal | Contains gluzincin signature motifs (H201EXXH and E242XXXD); forms a domain-swapped dimer [10] | Upon activation, cleaves the BlaI repressor and undergoes autocleavage [10] [11] |

Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures have revealed that full-length BlaR1 functions as an extensive domain-swapped dimer, a configuration critical for stabilizing its signaling loops [10]. The protein exhibits an unusual Nout, Cout topology, with both termini residing on the extracellular side of the membrane [10]. The dimer interface creates a central cavity that is likely filled with lipids, including phosphatidylglycerol, which may play a role in structural stability or signaling [10].

Signal Transduction Mechanism: From Antibiotic Binding to Gene Derepression

The activation of BlaR1 and the subsequent induction of resistance involve a sophisticated, multi-step signal transduction pathway. The process, from initial antibiotic sensing to the final expression of resistance genes, is outlined below and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The BlaR1-mediated signal transduction pathway leading to β-lactam antibiotic resistance in S. aureus. The pathway initiates with antibiotic binding and culminates in the expression of resistance proteins.

Key Steps in Pathway Activation:

- Antibiotic Sensing and Acylation: The process initiates when a β-lactam antibiotic enters the bacterial periplasm and covalently acylates the conserved serine residue (Ser389) within the active site of the BlaRS sensor domain [8]. This acylation event is the critical initial signal.

- Transmembrane Signal Transduction: Acylation triggers dynamic structural perturbations within BlaRS. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) relaxation studies indicate that these changes propagate from the antibiotic-binding pocket to the β5/β6 hairpin, a region known to interact with the extracellular L2 loop [8]. This interaction is proposed to alter the orientation or embedding of the connected transmembrane helices (specifically TM3), thereby transducing the signal across the membrane [8] [10].

- Protease Domain Activation and Autocleavage: The signal allosterically activates the cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain. This domain undergoes spontaneous autocleavage in cis between residues Ser283 and Phe284, a process that is enhanced upon antibiotic binding [10] [11]. This autocleavage is thought to shift the domain's equilibrium to a state permissive for BlaI cleavage [10].

- Repressor Cleavage and Gene Derepression: The activated BlaR1 protease directly cleaves the DNA-binding repressor protein, BlaI [10]. Degradation of BlaI derepresses the transcription of the bla operon (and in some strains, the mecA gene), leading to the expression of the β-lactamase BlaZ and the alternative penicillin-binding protein PBP2a, which collectively confer resistance [8] [10] [11].

Quantitative Data on BlaR1 Function and Inhibition

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings related to BlaR1's activity and the pharmacological inhibition of its signaling pathway.

Table 2: Documented BlaR1 Proteolytic Events

| Proteolytic Event | Cleavage Site | Functional Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autocleavage | Ser283-Phe284 [10] | Proposed to activate the protease domain towards BlaI; a step in the turnover/recovery process [10] [11] | Edman N-terminal sequencing; Cryo-EM structure of F284A mutant [10] |

| Sensor Domain Shedding | Not fully characterized [11] | Proposed to facilitate recovery from induction after antibiotic removal [11] | Western blot detection of soluble BlaRS fragments in culture media [11] |

Table 3: Efficacy of Representative Kinase Inhibitors in Reversing MRSA Resistance

| Inhibitor Compound | Original Indication | MIC of Oxacillin (μg/mL) with Inhibitor | Effect on BlaR1 Phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Compound 1 | Mammalian serine/threonine kinase inhibitor [5] | Not specified (4-fold decrease vs. control) [5] | Inhibited both phosphotyrosine and phosphoserine (70-90% reduction) [5] |

| Optimized Inhibitor 10 | Synthetic derivative [5] | 2 (vs. 256 in MRSA252 control) [5] | Abolished tyrosine phosphorylation; no effect on serine phosphorylation [5] |

| Optimized Inhibitor 11 | Synthetic derivative [5] | 16 (vs. 256 in MRSA252 control) [5] | Abolished tyrosine phosphorylation; no effect on serine phosphorylation [5] |

| Optimized Inhibitor 12 | Synthetic derivative [5] | 4 (vs. 256 in MRSA252 control) [5] | Abolished tyrosine phosphorylation; no effect on serine phosphorylation [5] |

MIC: Minimal Inhibitory Concentration.

Experimental Protocols for BlaR1 Research

This section outlines core methodologies for investigating the structure and function of BlaR1, supporting research into its mechanism and inhibition.

Objective: To produce isotopically labeled, purified BlaRS domain for structural and dynamic studies using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Materials:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) cells with pET28b plasmid encoding S. aureus BlaR1 residues 329-585.

- M9 minimal medium adjusted for U-15N and U-13C/15N labeling.

- Lysis Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.0.

- Purification columns: HI-TRAP SP cation-exchange column, S200 gel-filtration column.

- NMR Buffer: 20 mM NaH2PO4, 30 mM NaCl, 90/10% H2O/D2O, 0.02% NaN3.

Method:

- Cell Growth and Induction: Grow E. coli cells to OD600 ~0.7 in LB media. Pellet cells and resuspend in 250 mL of isotopic labeling M9 medium. Incubate at 24°C for 30 minutes, then induce protein expression with 1 mM IPTG for 20 hours.

- Cell Lysis: Pellet cells and resuspend in lysis buffer. Lyse by sonication on ice (6 minutes total, 10s on/50s off cycles) in the presence of lysozyme (5 mg) and a protease inhibitor tablet.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the lysate at 35,000g for 20 minutes to separate the soluble supernatant.

- Protein Purification: Load the supernatant onto a HI-TRAP SP cation-exchange column. Elute the protein using a linear salt gradient (200-800 mM NaCl). Pool fractions containing BlaRS and further purify via size-exclusion chromatography on an S200 column pre-equilibrated with 20mM NaH2PO4 and 150 mM NaCl.

- Sample Preparation for NMR: Concentrate the purified protein to ~300 μM and exchange into the final NMR buffer.

Objective: To detect and quantify the phosphorylation of BlaR1 in S. aureus upon exposure to β-lactam antibiotics and kinase inhibitors.

Materials:

- S. aureus strains (e.g., NRS128, MRSA252).

- Inducing antibiotic: e.g., CBAP (10 μg/mL).

- Kinase inhibitors for testing.

- Lysis buffer for bacterial pellets.

- Primary antibodies: anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-phosphoserine.

- Secondary antibody: stabilized goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated antibody.

- Western blotting apparatus and chemiluminescence detection system.

Method:

- Bacterial Culture and Treatment: Grow S. aureus cultures to exponential phase (A625 ~0.8). Divide the culture into aliquots and treat with: a) no antibiotic (control), b) CBAP inducer, c) CBAP + various concentrations of kinase inhibitor.

- Sample Collection: Incubate cultures and collect 5 mL aliquots at specific time points (e.g., 15, 30, 60, 180 min). Centrifuge to separate cell pellets and culture supernatants.

- Whole-Cell Extract Preparation: Resuspend cell pellets in an appropriate lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and lysostaphin (200 μg/mL). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to digest the cell wall.

- Western Blot Analysis: Quantify total protein. Load 60-80 μg of total protein per lane on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, transfer proteins to a nitrocellulose membrane.

- Immunodetection: Block the membrane and probe with primary antibodies against phosphotyrosine or phosphoserine, followed by the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Develop the blot using a chemiluminescent substrate and visualize. The phosphorylation level can be quantified by the band intensity relative to the control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for BlaR1 Mechanistic Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant BlaRS Domain | Soluble, purified extracellular sensor domain for biophysical and structural studies [8] | NMR analysis of acylation-induced dynamics [8]; X-ray crystallography [12] |

| BOCILLIN FL | Fluorescent penicillin derivative used to label and track active-site acylation [10] | Monitoring BlaR1 expression and ligand binding during purification [10] |

| Synthetic Kinase Inhibitors (e.g., 10, 11, 12) | Small molecules that inhibit BlaR1 phosphorylation, reversing resistance [5] | Restoring β-lactam susceptibility in MRSA strains; probing phosphorylation role [5] |

| Anti-Phosphoamino Acid Antibodies | Specific antibodies to detect tyrosine or serine phosphorylation [5] | Western blot analysis of BlaR1 activation status in bacterial extracts [5] |

| Cryo-EM Structure (PDB) | High-resolution structural model of full-length BlaR1 dimer [10] | Molecular docking for inhibitor design; understanding signal transduction mechanism [10] |

| L2 Loop Peptide | Peptide corresponding to the C-terminal half of the extracellular L2 loop [8] | NMR PRE experiments to probe BlaRS-L2 interaction and its role in signaling [8] |

Concluding Remarks and Research Outlook

The delineation of BlaR1's molecular architecture, particularly through recent cryo-EM structures, provides an unprecedented atomic-level view of its function as a central hub for inducible β-lactam resistance [10]. The intricate signaling pathway involving antibiotic acylation, transmembrane helix perturbation, protease domain activation, and repressor cleavage presents multiple vulnerable nodes for therapeutic intervention. The demonstrated success of kinase inhibitors in abrogating BlaR1 phosphorylation and resensitizing MRSA to penicillins validates this protein as a high-value target [5]. Future research should leverage the structural and mechanistic insights summarized in this note to design and optimize next-generation BlaR1 inhibitors. Combining such agents with traditional β-lactams represents a promising strategy for resurrecting the efficacy of this critical antibiotic class and overcoming MRSA resistance.

Acylation-induced conformational activation represents a fundamental biological control mechanism where the covalent attachment of lipid chains to proteins induces specific three-dimensional structural changes, thereby regulating protein function, localization, and signaling activity. This mechanism is particularly relevant in the context of antimicrobial resistance, where bacterial signaling pathways control the expression of resistance factors. Within the broader thesis on BlaR sensor inhibitors for MRSA resensitization, understanding acylation-mediated activation provides a foundation for targeting the conformational switching mechanisms that underlie β-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Protein S-acylation, particularly S-palmitoylation, serves as a reversible molecular switch that profoundly influences protein-membrane interactions, protein stability, and signal transduction complexes [13]. The dynamic nature of this modification, controlled by opposing enzymatic activities of acyltransferases and deacylases, allows cells to rapidly adapt their signaling networks in response to environmental cues [13] [14].

In MRSA, the BlaR1 sensor transmembrane protein represents a critical signaling component that detects β-lactam antibiotics and transduces this information to initiate resistance mechanisms. While the specific acylation status of BlaR1 requires further characterization, the broader principles of acylation-induced conformational changes offer valuable insights for therapeutic intervention. The development of BlaR sensor inhibitors that block signal transduction and resensitize MRSA to conventional antibiotics represents a promising approach to combat antimicrobial resistance [15]. This application note details experimental frameworks for investigating acylation-mediated conformational activation in bacterial signaling systems, with specific relevance to BlaR1 function and inhibition.

Background: Acylation as a Regulatory Mechanism

Types and Biochemical Properties of Protein Acylation

Protein acylation encompasses several distinct chemical modifications involving the attachment of fatty acid chains to specific amino acid residues. The chemical properties of the attached lipid moiety significantly influence the functional consequences on the target protein:

- S-palmitoylation: The reversible attachment of a 16-carbon palmitic acid to cysteine residues via a thioester bond, catalyzed by DHHC-type acyltransferases [13]. This modification enhances protein hydrophobicity, facilitating membrane association and partitioning into lipid rafts.

- N-myristoylation: The co-translational attachment of a 14-carbon myristic acid to glycine N-terminal residues via a stable amide bond [14]. This modification often works in concert with palmitoylation to strengthen membrane anchoring.

- Lysine Acylations: Various short-chain acyl modifications (acetylation, succinylation, malonylation) that alter charge properties and structural conformations of target proteins [14] [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Acylation Types

| Acylation Type | Amino Acid Modified | Lipid Chain Length | Enzymatic Regulation | Key Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-palmitoylation | Cysteine (thioester) | C16 (primarily) | ZDHHC enzymes (writers); acyl-thioesterases (erasers) | Membrane targeting, lipid raft partitioning, protein stability |

| N-myristoylation | N-terminal Glycine (amide) | C14 | N-myristoyltransferases | Weak membrane association, often combinatorial with palmitoylation |

| S-acylation (general) | Cysteine | C14-C18 | DHHC-containing enzymes | Reversible membrane association, conformational switching |

| Lysine acetylation | Lysine | C2 | KATs/HDACs | Charge neutralization, altered protein-protein interactions |

Molecular Mechanisms of Conformational Activation

Acylation induces protein activation through several interconnected biophysical mechanisms:

Membrane Anchoring: The addition of hydrophobic lipid chains dramatically increases protein affinity for cellular membranes, facilitating translocation from cytosol to membrane compartments and enabling interactions with membrane-resident signaling partners [13].

Allosteric Rearrangements: Covalent lipid attachment can induce long-range conformational changes that alter protein activity by affecting active site accessibility, protein-protein interaction interfaces, or catalytic efficiency [14].

Stabilization of Active States: Acylation can preferentially stabilize specific protein conformations, shifting the equilibrium between inactive and active states toward functionally competent forms [13].

In the context of bacterial signaling, these mechanisms are exploited by pathogens to regulate virulence and resistance pathways. For MRSA, interference with acylation-dependent conformational switching in the BlaR1 signaling system offers a potential route to disrupt antibiotic resistance.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Acylation-Dependent Conformational Changes in BlaR1

Purpose: To monitor structural rearrangements in BlaR1 following β-lactam binding and potential acylation modifications using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET).

Principle: Site-specific labeling of BlaR1 cytoplasmic domains with FRET donor-acceptor pairs enables real-time detection of distance changes associated with conformational switching during signal transduction.

Reagents:

- Purified BlaR1 sensor domain (BlaRs) and signaling domain

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit for cysteine substitutions

- Fluorophore pairs: Cy3-Cy5 or Alexa Fluor 488-Alexa Fluor 555

- β-lactam antibiotics (oxacillin, meropenem)

- Boronate-based BlaR inhibitor (compound 4) [15]

- Acyl-CoA donors (palmitoyl-CoA, myristoyl-CoA)

- ZDHHC acyltransferase inhibitors (2-bromopalmitate)

Procedure:

Cysteine-Scanning Mutagenesis:

- Introduce single cysteine residues at strategic positions in BlaR1 cytoplasmic domains (≥20Å apart).

- Confirm protein folding and function via circular dichroism and β-lactam binding assays.

Fluorophore Labeling:

- Incubate cysteine mutants with 10-fold molar excess of thiol-reactive fluorophores.

- Remove unbound dye using desalting columns.

- Verify labeling efficiency via absorbance spectroscopy.

FRET Measurements:

- Set up reaction mixtures containing 100 nM labeled BlaR1 in signaling buffer.

- Acquire baseline FRET efficiency for 5 minutes.

- Add experimental treatments:

- Group A: β-lactam antibiotic (oxacillin, 10μg/mL)

- Group B: β-lactam + BlaR inhibitor (compound 4, 5μM) [15]

- Group C: Acyl-CoA donor (palmitoyl-CoA, 50μM)

- Group D: Acyltransferase inhibitor (2-bromopalmitate, 100μM)

- Monitor FRET efficiency changes for 30 minutes post-stimulation.

- Calculate distance changes using Förster equation.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize FRET efficiency to baseline values.

- Compare maximum response amplitudes and kinetics across treatment groups.

- Statistical analysis via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing.

Troubleshooting:

- Low FRET efficiency: Optimize cysteine placement using structural modeling.

- Non-specific labeling: Include reducing agents (1mM TCEP) to maintain cysteine specificity.

- High background: Include no-dye controls to subtract autofluorescence.

Protocol 2: Assessing Acylation-Dependent Membrane Association of BlaR1

Purpose: To quantify acylation-mediated translocation of BlaR1 signaling domains to membrane fractions in response to β-lactam exposure.

Principle: Cellular fractionation followed by immunoblotting allows tracking of protein redistribution between cytosolic and membrane compartments under different acylation conditions.

Reagents:

- MRSA cultures (ATCC 43300 reference strain)

- Lysis buffer (25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl) with protease inhibitors

- Ultracentrifugation equipment

- Acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) chemistry reagents

- Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate

- BlaR1-specific antibodies

- Subcellular fractionation kit

Procedure:

Bacterial Treatment and Fractionation:

- Culture MRSA to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.6).

- Divide into treatment groups:

- Control: No treatment

- β-lactam: Oxacillin (2μg/mL)

- Combination: Oxacillin + BlaR inhibitor (compound 4, 5μM)

- Acylation inhibition: 2-bromopalmitate (100μM) + oxacillin

- Incubate for 60 minutes at 37°C.

- Harvest cells and disrupt using French press or sonication.

- Separate membrane and cytosolic fractions via ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 60 minutes).

Acyl-Biotin Exchange Chemistry:

- Block free thiols with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM).

- Specifically cleave thioester-linked acyl groups with hydroxylamine (NH2OH).

- Label newly exposed thiols with biotin-HPDP.

- Capture biotinylated proteins with streptavidin beads.

- Detect BlaR1 in captured fractions via immunoblotting.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Normalize BlaR1 band intensity to membrane marker proteins.

- Calculate membrane-to-cytosol ratio for each treatment condition.

- Perform statistical comparisons across groups (n≥3 independent experiments).

Table 2: Expected Membrane Localization of BlaR1 Under Different Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Expected Effect on S-acylation | Predicted Membrane Localization | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no treatment) | Basal acylation | Low to moderate | Baseline reference |

| β-lactam antibiotic only | Induced acylation | Significant increase | Resistance activation |

| β-lactam + BlaR inhibitor | Inhibited acylation | Decreased vs. antibiotic alone | Resensitization mechanism |

| Acyltransferase inhibition | Blocked acylation | Markedly decreased | Confirmatory evidence |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

BlaR1 Signal Transduction and Inhibitor Mechanism

This diagram illustrates the BlaR1-mediated signal transduction pathway that activates β-lactam resistance in MRSA, highlighting the potential role of acylation in inducing conformational changes and the point of inhibition by benzimidazole-boronate compounds.

Experimental Workflow for Acylation Studies

This workflow outlines the integrated experimental approach for investigating acylation-induced conformational changes, combining biophysical measurements of protein structure with biochemical analysis of membrane association and acylation status.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Acylation and BlaR Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BlaR Inhibitors | Benzimidazole-boronate compound (4) [15] | Potentiates β-lactam activity by blocking BlaR sensor function | Restores antibiotic susceptibility (16- to 4,096-fold enhancement) |

| Acylation Modulators | 2-Bromopalmitate (2-BP); Palmitoyl-CoA | Inhibits ZDHHC acyltransferases; provides acyl donors for in vitro assays | May affect multiple acylation pathways; use appropriate controls |

| Natural Bioactive Compounds | Curcumin; Eugenol [17] | Downregulates mecA and agrA expression in MRSA | Reduces both resistance and virulence pathways; potential adjunct therapy |

| FRET Reagents | Cy3-Cy5; Alexa Fluor 488-555 pairs | Site-specific protein labeling for conformational studies | Optimize labeling efficiency while maintaining protein function |

| Acylation Detection | Acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) chemistry | Enrichment and detection of S-acylated proteins from complex mixtures | Hydroxylamine sensitivity confirms thioester linkage specificity |

| Structural Biology Tools | BlaR1 sensor domain constructs | X-ray crystallography of inhibitor-bound complexes [15] | Reveals covalent engagement with active site serine residues |

| Antibiotic Potentiation Assays | Oxacillin; Meropenem [15] | Checkerboard synergy testing with BlaR inhibitors | Measure fold-reduction in MIC values for resistance reversal |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Assessment of BlaR Inhibitor Efficacy

Table 4: BlaR Inhibitor-Mediated Resensitization of MRSA to β-Lactams

| MRSA Strain | Antibiotic Alone (MIC, μg/mL) | Antibiotic + Inhibitor (MIC, μg/mL) | Fold Reduction in MIC | Proposed Mechanism Linked to Acylation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 43300 | Oxacillin: 256 | Oxacillin + Compound 4: 0.062 | 4,096-fold [15] | Blocked signal transduction preventing resistance activation |

| Clinical isolate VITKV39 | Oxacillin: 512 | Oxacillin + Curcumin: 64 | 8-fold [17] | mecA downregulation affecting resistance machinery |

| Clinical isolate VITKV32 | Oxacillin: 256 | Oxacillin + Eugenol: 32 | 8-fold [17] | Dual agrA and mecA suppression targeting virulence and resistance |

| NRS119 (BlaR1+) | Meropenem: 128 | Meropenem + Compound 4: 8 | 16-fold [15] | Direct BlaR sensor domain inhibition preventing conformational activation |

Interpretation Guidelines

The quantitative data presented in Table 4 demonstrates the therapeutic potential of targeting BlaR1 signaling to restore β-lactam efficacy against MRSA. Key interpretation principles include:

Fold-Reduction Significance: ≥8-fold MIC reduction is considered biologically significant for resistance reversal, with greater reductions indicating more potent intervention [15].

Mechanistic Correlation: Compounds showing the greatest potentiation (e.g., compound 4 with 4,096-fold enhancement) likely target critical early steps in signal transduction, potentially involving acylation-dependent conformational switching [15].

Multi-Target Approaches: Natural compounds like curcumin and eugenol show more modest but mechanistically diverse effects, simultaneously targeting resistance (mecA) and virulence (agrA) pathways [17].

Therapeutic Implications: The magnitude of MIC reduction correlates with potential clinical efficacy, with combination approaches offering promise for resensitizing highly resistant MRSA strains to conventional antibiotics.

The investigation of acylation-induced conformational activation provides critical insights for developing innovative therapeutic strategies against antimicrobial resistance. The BlaR1 signaling system in MRSA represents a compelling model for understanding how bacterial sensors transduce extracellular signals (β-lactam detection) into intracellular responses (resistance gene expression). While direct evidence for BlaR1 acylation requires further experimental validation, the established principles of lipid modification-induced conformational changes offer a valuable framework for interrogating this system.

The development of benzimidazole-boronate BlaR inhibitors [15] demonstrates the therapeutic potential of disrupting signal transduction pathways that control antibiotic resistance. These compounds, particularly when used in combination with conventional β-lactams, represent a promising approach to extend the utility of existing antibiotics against resistant pathogens. Future research directions should include:

- Direct experimental demonstration of BlaR1 acylation status and its functional consequences

- High-resolution structural studies of full-length BlaR1 in different signaling states

- Exploration of potential crosstalk between acylation and other post-translational modifications in bacterial signaling

- Development of next-generation inhibitors targeting multiple nodes in the resistance signaling cascade

The integration of biophysical, biochemical, and microbiological approaches outlined in this application note provides a comprehensive framework for advancing our understanding of acylation-mediated signaling mechanisms and their therapeutic exploitation in the ongoing battle against antimicrobial resistance.

BlaR1 Fragmentation and the Role in Recovery from Induction

The BlaR1 protein in Staphylococcus aureus is an integral membrane protein that acts as the primary sensor for β-lactam antibiotics in the environment [1]. As a key component of the inducible bla operon, its activation initiates a signaling cascade that culminates in antibiotic resistance, a major challenge in treating Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections [1] [5]. While the mechanisms of resistance induction have been studied, the processes that enable bacteria to revert to a non-induced state upon antibiotic removal are equally critical for the regulatory cycle. This application note examines the phenomenon of BlaR1 fragmentation as a central mechanism in the recovery from induction, a process with significant implications for developing strategies to resensitize MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. We provide detailed protocols and data for researchers investigating BlaR1-targeting sensor inhibitors.

Molecular Mechanisms of BlaR1 Signaling and Fragmentation

BlaR1 Signal Transduction Pathway

BlaR1 functions as a sophisticated sensor-transducer. Its C-terminal extracellular domain binds β-lactam antibiotics, forming a stable acyl-enzyme complex [1] [3]. This acylation event triggers transmembrane signaling that activates the N-terminal cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain [3]. The activated protease then degrades the transcriptional repressor BlaI, derepressing the bla operon and leading to the expression of resistance determinants such as β-lactamase (BlaZ) and PBP2a [1] [3] [18].

Recent structural biology insights from cryo-EM studies reveal that BlaR1 exists as a domain-swapped dimer with an N-out, C-out topology, a rare architectural feature in bacterial membrane proteins [3]. Dimerization creates a central cavity lined with phosphatidylglycerol headgroups, suggesting lipid involvement in structure or function [3]. The cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain features a re-entrant loop and gluzincin signature motifs (H201EXXH and E242XXXD) crucial for its catalytic activity [3].

BlaR1 Fragmentation as a Regulatory Turnover Mechanism

The recovery from antibiotic-induced resistance requires termination of the BlaR1-mediated signal. Research demonstrates that BlaR1 undergoes specific proteolytic fragmentation within time frames relevant to resistance manifestation [1]. This fragmentation occurs at two primary locations: one within the cytoplasmic domain and another within the sensor domain [1].

The cytoplasmic cleavage event happens between residues Arg-293 and Arg-294 (numbered according to the specific strain used in the study), an autoproteolytic process that was initially thought to activate the protease domain but is now understood to be part of the protein's turnover mechanism [1]. The second fragmentation site in the sensor domain leads to shedding of this domain into the extracellular medium [1]. Notably, this fragmentation occurs even in non-acylated BlaR1, suggesting the proteolysis sites may have evolved to predispose the protein to degradation within a set timeframe, thus facilitating recovery from induction once the antibiotic challenge subsides [1].

The following diagram illustrates the BlaR1 signaling pathway and the critical role of fragmentation in the recovery process:

Figure 1: BlaR1 Signaling Pathway and Fragmentation-Mediated Recovery. β-lactam antibiotic acylation activates BlaR1, triggering signal transduction that cleaves the BlaI repressor and induces antibiotic resistance. Concurrent BlaR1 fragmentation facilitates recovery from induction once antibiotic pressure diminishes.

Quantitative Analysis of BlaR1 Fragmentation

Fragmentation Kinetics and Strain Variability

The fragmentation of BlaR1 exhibits distinct temporal patterns and strain-dependent characteristics. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from key studies investigating BlaR1 behavior across different S. aureus strains:

Table 1: BlaR1 Fragmentation Kinetics Across S. aureus Strains

| S. aureus Strain | Antibiotic Inducers Tested | Fragmentation Time Frame | Fragmentation Sites Identified | Detection Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS128 (NCTC8325) | PEN, AMP, OXA, CBAP | Within 15 min - 3 h post-induction | Cytoplasmic domain (Arg-293/Arg-294), Sensor domain | Clearly detected [1] |

| NRS123 (MW2, USA400) | PEN, AMP, OXA, CBAP | Relevant to resistance manifestation | Cytoplasmic and sensor domains | Detected [1] [5] |

| NRS70 (N315) | PEN, AMP, OXA, CBAP | Relevant to resistance manifestation | Cytoplasmic and sensor domains | Detected [1] [5] |

| MRSA252 | Not specified | Not fully characterized | Not fully characterized | Below detection threshold [1] |

Phosphorylation Status and Inhibitor Effects

Beyond proteolytic fragmentation, BlaR1 activity is regulated by phosphorylation events that influence the resistance phenotype:

Table 2: Phosphorylation Events in BlaR1 Signaling and Inhibitor Effects

| Parameter | Findings | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation Sites | Phosphorylation on at least one serine and one tyrosine residue in the cytoplasmic domain [5] | Western blot with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-phosphoserine antibodies [5] |

| Kinase Inhibitor Effects | Compound 1 (lead inhibitor) reduced phosphorylation by 70-90% and lowered oxacillin MIC 4-fold [5] | Growth assays with MRSA252; Western blot analysis [5] |

| Optimized Inhibitors | Compounds 10, 11, 12 abolished tyrosine phosphorylation at 7 μg/mL and significantly reduced oxacillin MIC [5] | Dose-response in NRS70; MIC determination across strains [5] |

| Functional Consequence | Tyrosine phosphorylation critical for resistance manifestation; serine phosphorylation role less clear [5] | Selective inhibition with optimized compounds [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring BlaR1 Fragmentation in S. aureus Cultures

This protocol enables researchers to track BlaR1 fragmentation dynamics in response to β-lactam induction, adapted from methodology in [1].

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strains: S. aureus strains (e.g., NRS128, NRS123, NRS70) from relevant repositories

- Antibiotics: Penicillin G (PEN), ampicillin (AMP), oxacillin (OXA), CBAP prepared as stock solutions

- Growth Medium: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth

- Lysis Buffer: 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaHCO₃, 1× Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM MgCl₂, 15 μg/mL DNase I, 15 μg/mL RNase A, 200 μg/mL lysostaphin

- Detection Reagents: SDS-PAGE equipment, Western blotting apparatus, anti-BlaR1 antibodies (polyclonal, generated against recombinant BlaRS)

Procedure

- Culture Preparation: Grow S. aureus strains overnight in LB medium at 37°C with shaking (220 rpm).

- Subculture: Dilute overnight culture 1:1000 in fresh LB and grow to exponential phase (A₆₂₅ ≈ 0.8, approximately 4 hours).

- Antibiotic Induction: Divide culture into aliquots and add sub-MIC concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics:

- 3.2-fold below MIC for PEN, AMP, OXA

- 6.4-fold below MIC for CBAP

- Maintain one aliquot as non-induced control

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect 5 mL aliquots at 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, and 3 h post-induction.

- Sample Processing:

- Centrifuge samples at 3,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C

- Reserve supernatant for β-lactamase activity assays

- Resuspend cell pellets in Lysis Buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 min

- Quantify total protein using BCA assay

- Analysis:

- Load 60-80 μg total protein per lane on Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels

- Perform Western blotting with anti-BlaR1 antibodies

- Detect fragmentation patterns using enhanced chemiluminescence

Key Observations

- BlaR1 fragmentation should be detectable within 15 minutes to 3 hours post-induction

- Multiple fragments may be observed: full-length (~75 kDa), cytoplasmic domain fragments (~40 kDa), and sensor domain fragments

- Fragmentation patterns may vary between strains

Protocol 2: Assessing BlaR1 Phosphorylation Status

This protocol details the detection of phosphorylation events in BlaR1 that regulate its function, based on methodology from [5].

Materials and Reagents

- Kinase Inhibitors: Compound 1 or optimized variants (10, 11, 12) dissolved in DMSO

- Inducer: CBAP (2-(2'-carboxyphenyl)-benzoyl-6-aminopenicillanic acid) at 10 μg/mL

- Antibodies: Anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-phosphoserine, anti-phosphothreonine antibodies

- Lysis Buffer: As in Protocol 1, supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (sodium orthovanadate, sodium fluoride, β-glycerophosphate)

Procedure

- Culture and Induction:

- Grow S. aureus NRS128 or MRSA252 to exponential phase as in Protocol 1

- Divide culture into aliquots for treatments:

- Non-induced control

- CBAP-induced (10 μg/mL)

- CBAP + kinase inhibitor (0.7 μg/mL and 7 μg/mL)

- Incubate for 1-3 hours at 37°C with shaking

- Whole-Cell Extract Preparation:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation

- Lyse cells using Lysis Buffer with phosphatase inhibitors

- Quantify protein concentration

- Phosphorylation Detection:

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE (60-80 μg per lane)

- Transfer to PVDF membrane

- Block with 5% BSA in TBST

- Probe with anti-phosphotyrosine (1:1000) or anti-phosphoserine (1:1000) antibodies

- Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

- Develop with ECL reagent

- Validation:

- Strip and reprobe membranes with anti-BlaR1 antibodies to confirm equal loading

- Compare phosphorylation signals across treatment conditions

Data Interpretation

- CBAP induction should increase tyrosine and serine phosphorylation

- Effective kinase inhibitors will reduce phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner

- Phosphotyrosine reduction should correlate with restored antibiotic susceptibility

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BlaR1 Fragmentation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CBAP (2-(2'-carboxyphenyl)-benzoyl-6-aminopenicillanic acid) | Gratuitous inducer of bla system; poor antimicrobial activity but excellent inducer [19] | Used at 10 μg/mL for induction; exposes hidden active site dynamics in BlaR1 [5] [19] |

| Anti-BlaR1 Antibodies | Detection of BlaR1 and its fragments in Western blotting | Polyclonal antibodies generated against recombinant BlaRS; allow detection of full-length and fragmented BlaR1 [1] |

| Kinase Inhibitors (Compounds 10, 11, 12) | Inhibition of BlaR1 phosphorylation; resensitization of MRSA to β-lactams [5] | Used at 0.7-7 μg/mL; specifically inhibit tyrosine phosphorylation of BlaR1 [5] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Detection of phosphorylation events in BlaR1 | Anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-phosphoserine antibodies; confirm absence of threonine phosphorylation [5] |

| Lysostaphin | Cell wall digestion for protein extraction from S. aureus | Used at 200 μg/mL in lysis buffer for efficient cell disruption [1] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Preservation of protein integrity during extraction | EDTA-free formulations recommended to preserve metalloprotease activity [1] |

Research Applications and Implications for MRSA Resensitization

The study of BlaR1 fragmentation provides critical insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies against MRSA. Research demonstrates that targeted disruption of BlaR1 signaling through kinase inhibition can restore β-lactam susceptibility in resistant strains [5]. For instance, optimized kinase inhibitors reduced the oxacillin MIC in MRSA252 from 256 μg/mL to as low as 2-16 μg/mL, effectively resensitizing this strain to the antibiotic [5].

Furthermore, simultaneous blockade of both BlaR1 and the homologous MecR1 signaling pathways through deoxyribozyme approaches has shown promise in restoring susceptibility across diverse MRSA clinical isolates [20]. This strategy is particularly valuable given the cross-regulation between the bla and mec operons in many clinical strains [20] [18].

Understanding BlaR1 fragmentation mechanisms also opens avenues for developing allosteric inhibitors that might potentiate the natural turnover process, preventing sustained induction of resistance even after antibiotic exposure. The identification of specific fragmentation sites provides potential targets for small molecules that could accelerate BlaR1 inactivation and promote recovery from the induced resistance state [1].

These approaches, framed within the broader context of BlaR sensor inhibition, represent promising avenues for overcoming MRSA resistance and extending the utility of existing β-lactam antibiotics through combination therapies with sensor pathway inhibitors.

The escalating global burden of antimicrobial resistance places Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as a paramount public health threat. The efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics, the gold standard for treating staphylococcal infections, is neutralized by sophisticated resistance mechanisms in MRSA. Central to these mechanisms are the sensor-transducer proteins BlaR1 and MecR1, which regulate the expression of resistance determinants. This application note provides a comparative analysis of MecR1 and BlaR1 functional homology, framing it within the strategic development of BlaR1 sensor inhibitors for MRSA resensitization. A thorough understanding of their synergistic and distinct roles is critical for exploiting BlaR1 as a therapeutic target to restore β-lactam efficacy [21] [22] [3].

Comparative Analysis of BlaR1 and MecR1 Signaling Systems

The inducible β-lactam resistance in S. aureus is governed by two homologous regulatory divergons: the bla system (blaR1-blaI-blaZ) and the mec system (mecR1-mecI-mecA). These systems sense extracellular β-lactams and initiate a signal transduction cascade that culminates in the expression of antibiotic-inactivating proteins [3].

BlaR1 and MecR1 are integral membrane proteins that function as the primary sensors for β-lactam antibiotics. Although they share only 35% sequence identity, they exhibit remarkable functional homology and nearly identical domain architecture [3]. Both proteins possess an extracellular penicillin-binding sensor domain, a transmembrane region, and a cytosolic zinc metalloprotease domain. Upon binding β-lactams, a conformational change triggers the proteolytic activity of the cytoplasmic domain, leading to the cleavage of their respective repressors, BlaI or MecI [23] [3].

Table 1: Core Functional Homology and Distinctions Between BlaR1 and MecR1

| Feature | BlaR1 | MecR1 | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | β-lactam sensor/signal transducer [3] | β-lactam sensor/signal transducer [24] | Functional homologs; initiate resistance cascade |

| Induced Gene | blaZ (β-lactamase PC1) [3] |

mecA (PBP2a) [24] |

BlaZ inactivates penicillin; PBP2a provides broad-spectrum resistance |

| Repressor Protein | BlaI [3] | MecI [24] | Homologous DNA-binding repressors (61% identity) |

| Sensor Domain Architecture | Near-identical to class D β-lactamases [3] | Near-identical to class D β-lactamases [3] | Both bind β-lactams via acylation of active site serine |

| Proteolytic Action | Direct cleavage of BlaI repressor [3] | Presumed direct cleavage of MecI repressor [24] | Inactivates repressor, derepressing resistance gene transcription |

| Cross-Regulation | Can induce mecA expression in some strains [3] |

- | BlaR1 can be the primary inducer of PBP2a in clinical MRSA |

A critical finding for drug development is the phenomenon of cross-regulation. In many clinically prevalent MRSA strains, particularly those carrying SCCmec type IV (like the epidemic USA300 clone), the native mecI and mecR1 genes are truncated or deleted. In these strains, the BlaR1-BlaI system assumes control over the expression of mecA-encoded PBP2a. This makes BlaR1 the dominant and sometimes sole sensor responsible for initiating broad-spectrum β-lactam resistance in many dangerous MRSA clones, thereby elevating its strategic importance as a therapeutic target [3].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating BlaR1/MecR1 Function and Inhibition

Protocol: Recombinant Expression and Purification of BlaR1 for Structural and Biochemical Studies

Objective: To obtain functional, full-length BlaR1 protein for in vitro assays, structural studies, and inhibitor screening.

Background: The historical challenge in BlaR1 biochemistry has been obtaining adequate quantities of stable, active protein. This protocol, adapted from a seminal 2023 Nature study, utilizes a prokaryotic expression system to overcome this hurdle [3].

Materials:

- Expression Vector: Nisin-controlled gene expression (NICE) system.

- Host Strain: Lactococcus lactis [3].

- Detergent: Appropriate detergent for membrane protein solubilization (e.g., DDM).

- Chromatography: HisTrap FF crude column and Superdex size-exclusion column.

- Fluorescent β-lactam: BOCILLIN FL for activity monitoring [3].

Methodology:

- Cloning and Transformation: Clone the full-length

blaR1gene from a relevant MRSA strain (e.g., USA300) into the NICE system expression vector. Transform the construct into L. lactis. - Membrane Preparation:

- Induce expression with nisin when the culture reaches mid-log phase.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and disrupt using a high-pressure homogenizer.

- Isolate the membrane fraction by ultracentrifugation.

- Solubilization and Purification:

- Solubilize membranes with a suitable detergent.

- Purify the protein using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) via an engineered His-tag.

- Further purify the protein using rate-zonal ultracentrifugation to enrich for intact oligomeric species.

- Perform a final polishing step using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) in a buffer compatible with downstream applications.

- Quality Control:

- Assess purity by SDS-PAGE.

- Monitor autocleavage status via Western blot or Edman sequencing.

- Confirm β-lactam binding capability using BOCILLIN FL.

Protocol: Assessing BlaR1 Inhibition and Antibiotic Resensitization

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of BlaR1 kinase inhibitors in resensitizing MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics.

Background: BlaR1's signal transduction involves phosphorylation; abrogation of this phosphorylation by small-molecule inhibitors can restore bacterial susceptibility to penicillins [23].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: MRSA strain with functional BlaR1 regulating

mecA(e.g., USA300). - Inhibitors: Synthetic protein kinase inhibitors.

- Antibiotics: Penicillin G or methicillin.

- Growth Media: Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth.

- Standard MIC Determination Equipment.

Methodology:

- Checkerboard Assay Setup:

- Prepare a dilution series of the BlaR1 kinase inhibitor in a 96-well plate.

- Cross-dilute with a series of a β-lactam antibiotic (e.g., penicillin).

- Inoculate each well with a standardized suspension of the MRSA test strain.

- Incubation and Analysis:

- Incubate the plate at 37°C for 18-24 hours.

- Determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the β-lactam antibiotic in the presence and absence of the inhibitor.

- Calculate the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index to determine synergy between the inhibitor and the antibiotic.

- Mechanistic Confirmation:

- To confirm target engagement, use Western blot analysis to monitor the levels of phosphorylated BlaR1 and the cleavage of BlaI in inhibitor-treated cells exposed to β-lactams [23].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for BlaR1/MecR1 Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Nisin-Controlled Expression (NICE) System | High-yield recombinant BlaR1 production [3] | Uses L. lactis; overcomes historical challenges of BlaR1 expression and isolation. |

| BOCILLIN FL | Fluorescent β-lactam for sensor domain activity [3] | Covalently labels the active site serine; used for monitoring protein folding and ligand binding. |

| Synthetic Protein Kinase Inhibitors | Abrogate BlaR1-mediated resistance [23] | Reverse BlaR1 phosphorylation, preventing signal transduction and restoring penicillin susceptibility. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard buffer for biochemical assays | Must be fresh; some boronic-acid based warheads can degrade in phosphate buffer over time [25]. |

| Ampicillin / Oxacillin | Prototypical β-lactam inducers | Used in experiments to induce the BlaR1/BlaI and MecR1/MecI signaling pathways. |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

BlaR1/MecR1 β-Lactam Resistance Signaling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for BlaR1 Inhibitor Screening

The comparative analysis of MecR1 and BlaR1 underscores a compelling functional homology, with BlaR1 emerging as a master regulator of β-lactam resistance in many dominant MRSA clones. The detailed protocols for protein characterization and inhibitor screening provided herein establish a foundational toolkit for research aimed at BlaR1 disruption. Targeting the BlaR1 sensor with small-molecule inhibitors represents a promising adjuvant strategy, capable of resensitizing MRSA to conventional β-lactam antibiotics and resurrecting their therapeutic utility. Future work should focus on optimizing lead inhibitors for potency and pharmacokinetic properties, paving the way for novel combination therapies against intractable MRSA infections.

From Discovery to Design: Screening and Developing Potent BlaR1 Inhibitors

High-Throughput In Silico Screening for BlaR1 Sensor Domain Binders

The BlaR1 receptor in Staphylococcus aureus is a transmembrane antibiotic sensor and signal transducer that plays a critical role in mediating β-lactam resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [3] [26]. This protein detects the presence of β-lactam antibiotics in the extracellular environment and initiates a signaling cascade that culminates in the expression of antibiotic resistance genes, including blaZ (encoding β-lactamase PC1) and mecA (encoding the β-lactam-resistant cell-wall transpeptidase PBP2a) [3]. The sensor domain of BlaR1 (BlaRS), located extracellularly, specifically recognizes and covalently binds β-lactam antibiotics through acylation of a conserved serine residue [26] [27]. This binding event triggers a conformational change that is transduced across the bacterial membrane, ultimately activating the cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain of BlaR1, which then cleaves the BlaI repressor protein [3]. Degradation of BlaI derepresses the transcription of resistance genes, allowing the bacterium to survive antibiotic challenge [3] [26].

In the context of MRSA resensitization strategies, the BlaR1 sensor domain presents an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Inhibiting BlaR1 signal transduction can prevent the expression of β-lactamase and PBP2a, potentially restoring the efficacy of existing β-lactam antibiotics [28] [20]. This application note details a comprehensive protocol for the high-throughput in silico screening of compound libraries to identify novel, potent binders of the BlaR1 sensor domain, with the ultimate aim of developing adjuvant therapies that resensitize MRSA to conventional antibiotics.

Background and Significance

BlaR1 Structure and Signal Transduction Mechanism

Full-length BlaR1 is a multi-domain protein featuring an extracellular C-terminal sensor domain (BlaRS), transmembrane helices, and an N-terminal cytoplasmic zinc metalloprotease domain [3]. Recent cryo-electron microscopy structures have revealed that BlaR1 forms a domain-swapped dimer, a configuration that stabilizes the signaling loops within the protein [3]. The sensor domain shares architectural similarities with class D β-lactamases and undergoes a unique acylation-dependent activation mechanism [3] [27].

The signal transduction mechanism involves several key steps, illustrated in the pathway diagram below:

Diagram Title: BlaR1-Mediated Antibiotic Resistance Pathway

Upon β-lactam binding, a conserved serine residue in the BlaRS active site becomes acylated [26]. This acylation event initiates a conformational rearrangement that propagates from the antibiotic-binding pocket to the adjacent β5/β6 hairpin, a region known to interact with the extracellular L2 loop proximal to the transmembrane helix 3 [26]. These changes ultimately trigger the activation of the intracellular metalloprotease domain, which cleaves and inactivates the BlaI repressor, leading to the expression of resistance genes [3] [26]. The allosteric network within BlaRS, revealed by NMR studies, shows that acylation-induced perturbations communicate through specific residues to the protein regions interfacing with the membrane, thereby enabling transmembrane signaling [26].

BlaR1 as a Therapeutic Target for MRSA Resensitization

The central role of BlaR1 in regulating β-lactam resistance makes it a compelling target for disarming MRSA defense mechanisms. Strategies aimed at inhibiting BlaR1 function seek to block the induction of resistance rather than directly kill the bacterium, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance development. Research has demonstrated that simultaneous blockade of both BlaR1 and its homolog MecR1 via deoxyribozymes can significantly restore β-lactam susceptibility in clinical MRSA isolates, underscoring the viability of this approach [20].

The BlaR1 sensor domain is particularly amenable to targeting by small molecules due to its well-defined structure and characterized binding pocket. As highlighted in structural studies, the domain possesses an allosteric site distal to the active site [28]. Compounds binding to this allosteric site could potentially lock BlaR1 in an inactive conformation, preventing signal transduction upon antibiotic exposure. High-throughput in silico screening offers a powerful and efficient method to identify such inhibitory compounds from vast chemical libraries, accelerating the discovery of novel BlaR1-targeted adjuvants.

Computational Methods and Protocols

Target Preparation for BlaR1 Sensor Domain

The initial and critical step for successful virtual screening is the meticulous preparation of the BlaR1 sensor domain (BlaRS) structure.

Protocol 3.1.1: Structure Retrieval and Selection

- Obtain the atomic coordinates of the BlaRS domain from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prioritize structures with high resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Å) and relevant ligation states.

- Key structures for consideration include:

- Apo BlaRS (PDB: 4DLK): Represents the unliganded, pre-acylation state [26].

- Acylated BlaRS (e.g., with penicillin G or CBAP): Captures the post-acylation, activated conformation. The structure with CBAP (2-(2'-carboxyphenyl)-benzoyl-6-aminopenicillanic acid) is particularly valuable as this gratuitous inducer exposes hidden active site dynamics and can help identify multiple binding poses [29].

- Remove crystallographic water molecules and other non-essential heteroatoms, though consider retaining structurally conserved water molecules that may mediate ligand interactions.

Protocol 3.1.2: Structure Optimization and Refinement

- Use molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro, MOE, or UCSF Chimera) to add missing hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states to ionizable residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) at physiological pH (7.4).

- Perform limited energy minimization on the protein structure, typically constraining the heavy atoms to their crystallographic positions, to relieve steric clashes and optimize hydrogen bonding networks. This step ensures a chemically reasonable and stable starting structure for docking.

Compound Library Preparation

Screening libraries must be carefully curated and prepared to ensure chemical diversity and drug-like properties.

Protocol 3.2.1: Library Curation and Filtering

- Source compound libraries from commercial vendors (e.g., ZINC, eMolecules) or in-house collections. Libraries should contain 1,000,000 to 10,000,000 compounds for primary screening.

- Apply pre-defined filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties. Standard filters include:

- Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS): Remove compounds with substructures known to cause false-positive assay results.

- Rule of Five (Lipinski's Rules): Prioritize compounds with molecular weight ≤ 500, calculated LogP ≤ 5, hydrogen bond donors ≤ 5, and hydrogen bond acceptors ≤ 10 to enhance the likelihood of oral bioavailability.

- Reactive Functional Groups: Remove compounds containing chemically reactive moieties (e.g., aldehydes, epoxides, Michael acceptors) that may covalently and non-specifically modify the protein.

Protocol 3.2.2: Ligand Energy Minimization and Tautomer Enumeration

- Generate plausible tautomeric and ionization states for each compound at pH 7.4 ± 0.5.

- Perform energy minimization on each ligand structure using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MMFF94 or OPLS4) to obtain a low-energy, stable 3D conformation. The output should be a library of 3D structures in a format suitable for docking (e.g., SDF or MOL2).

Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening Workflow

The core screening process involves docking each compound from the prepared library into the binding site of the prepared BlaRS structure. The workflow below outlines the key stages:

Diagram Title: Virtual Screening Workflow for BlaRS Binders

Protocol 3.3.1: Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

- Define the docking search space (grid) based on the known active site of BlaRS. The grid should encompass the serine nucleophile (e.g., Ser389 in S. aureus), the surrounding acylation pocket, and the adjacent β5/β6 hairpin region implicated in allosteric signaling [26].

- For a more comprehensive search, generate an additional grid box encompassing the reported allosteric site distal to the active site to identify non-substrate-like inhibitors that may function via allosteric mechanisms [28].

Protocol 3.3.2: High-Throughput Docking and Scoring

- Employ a docking program (e.g., Glide, AutoDock Vina, or FRED) to computationally predict the binding pose and affinity of each compound within the defined grid.

- Use a standardized docking protocol with a balanced search exhaustiveness to ensure a thorough exploration of conformational space without prohibitive computational cost.

- Score each generated pose using the software's native scoring function. Rank the entire library based on this docking score, which provides an estimate of the binding free energy.

Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Selection

Protocol 3.4.1: Pose Filtering and Clustering

- From the top-ranked 1,000-5,000 compounds, manually or automatically filter out poses with poor chemical geometry, insufficient contact with key binding site residues, or lack of specific interactions.

- Cluster the remaining hits based on chemical scaffold similarity to ensure structural diversity among selected candidates.

Protocol 3.4.2: Interaction Analysis and Final Selection

- Visually inspect the predicted binding modes of the top-ranked compounds from each cluster. Prioritize compounds that form specific interactions critical for high-affinity binding, such as:

- Hydrogen bonds with the protein backbone or side chains in the active site.

- Hydrophobic interactions with non-polar residues lining the pocket.

- Salt bridges or cation-π interactions with residues like Lys or Arg.

- Pay special attention to compounds that may act as covalent inhibitors by forming a reversible or irreversible bond with the active site serine. While non-covalent inhibitors are generally preferred for their safety profile, a well-designed covalent inhibitor could provide prolonged suppression of BlaR1 signaling.

- Select a final set of 50-100 diverse compounds with favorable predicted binding modes and scores for subsequent experimental validation.

- Visually inspect the predicted binding modes of the top-ranked compounds from each cluster. Prioritize compounds that form specific interactions critical for high-affinity binding, such as:

Key Experimental Validation Assays

Biochemical and Biophysical Assays

Protocol 4.1.1: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Binding Kinetics

- Immobilize: Purify the BlaRS domain and immobilize it onto a CM5 sensor chip via amine coupling.

- Analyte Dilution: Serially dilute the hit compounds (typically from 0.1 nM to 100 µM) in HBS-EP running buffer.

- Run Kinetics: Inject the analyte solutions over the immobilized BlaRS surface at a flow rate of 30 µL/min. Monitor the association and dissociation phases in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting sensorgrams to a 1:1 binding model to determine the association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD). High-throughput SPR systems, such as the Carterra LSA, can dramatically accelerate this process, enabling the screening of hundreds of candidates [30].

Protocol 4.1.2: NMR Chemical Shift Perturbation

- Prepare isotopically labeled (15N) BlaRS protein as described in previous studies [26].

- Acquire a 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum of the apo protein.

- Titrate in the hit compound and record spectra at increasing compound:protein ratios.

- Monitor changes in chemical shifts of backbone amide resonances. Residues experiencing significant chemical shift perturbations upon compound binding are mapped onto the BlaRS structure to identify the binding site, confirming the in silico predictions.

Functional and Cellular Assays

Protocol 4.2.1: β-Lactamase Induction Assay

- Grow a susceptible MRSA strain (e.g., USA300) to mid-log phase in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of a β-lactam antibiotic (e.g., cefoxitin) to induce resistance.

- Co-incubate the culture with varying concentrations of the hit compound.

- Measure β-lactamase activity periodically using a nitrocefin hydrolysis assay. Nitrocefin is a chromogenic cephalosporin that changes color from yellow to red upon hydrolysis by β-lactamase. A reduction in the rate of color change compared to the untreated control indicates successful inhibition of BlaR1-mediated induction.

Protocol 4.2.2: Checkerboard Synergy Assay

- In a 96-well microtiter plate, prepare a two-dimensional dilution series of a β-lactam antibiotic (e.g., oxacillin) and the hit compound.

- Inoculate each well with a standardized suspension of MRSA.

- Incubate the plate and measure the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for both agents alone and in combination.

- Calculate the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index to determine synergy (FIC index ≤ 0.5). A synergistic interaction indicates that the hit compound resensitizes MRSA to the β-lactam antibiotic.

Research Reagent Solutions