Biomolecular Condensates Compared: From Fundamental Principles to Therapeutic Targeting

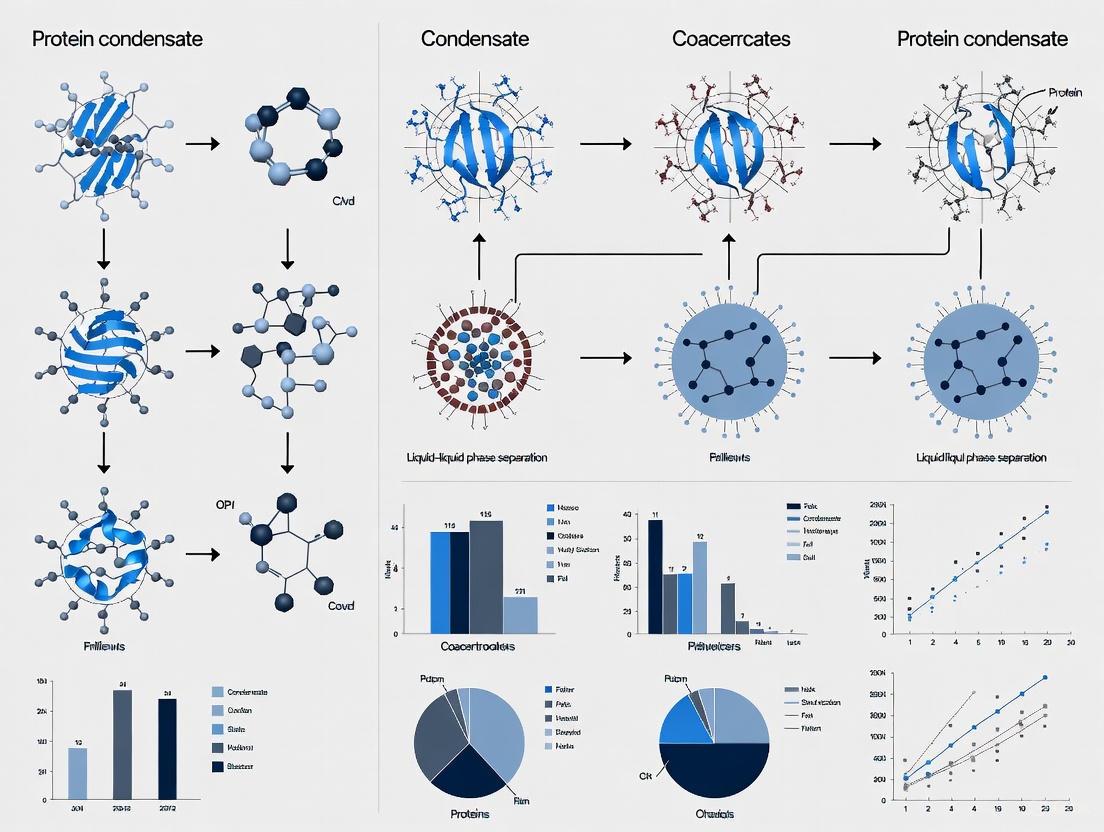

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of biomolecular condensate systems, membraneless organelles formed via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) that are pivotal for cellular organization and function.

Biomolecular Condensates Compared: From Fundamental Principles to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of biomolecular condensate systems, membraneless organelles formed via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) that are pivotal for cellular organization and function. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches, and current challenges in the field. We explore the diverse physical and chemical forces driving condensate assembly, compare state-of-the-art tools for studying their dynamic properties, and evaluate computational predictors for their accuracy and limitations. A significant focus is placed on the role of condensates in disease mechanisms, particularly cancer and neurodegeneration, and the emerging therapeutic strategy of developing condensate-modifying drugs (c-mods) to target these previously 'undruggable' systems. By integrating validation frameworks and comparative insights across different condensate types, this review aims to equip the scientific community with a structured understanding to advance both basic research and clinical applications.

The Physics and Biology of Biomolecular Condensates

Defining Biomolecular Condensates and Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS)

Biomolecular condensates are micron-scale compartments within eukaryotic cells that concentrate specific proteins and nucleic acids without the barrier of a surrounding membrane [1] [2]. They represent a fundamental mechanism of cellular organization, enabling the spatiotemporal control of complex biochemical reactions by concentrating reaction components to increase kinetics or segregating them to inhibit reactions [1]. These condensates are involved in diverse cellular processes, including RNA metabolism, ribosome biogenesis, the DNA damage response, and signal transduction [1] [3]. The term "biomolecular condensate" serves as an inclusive, detail-agnostic descriptor for a variety of structures previously known as membraneless organelles, nuclear bodies, granules, or puncta [1] [4] [2].

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) is the fundamental biophysical process responsible for forming many biomolecular condensates [5]. It describes the spontaneous demixing of a homogeneous solution into two distinct liquid phases: a dense phase (the condensate) enriched with biomolecules, and a surrounding dilute phase [1] [5]. This process is driven by multivalent, weak, transient interactions between proteins and nucleic acids [1] [4]. While the oil-and-water demixing analogy is a useful introduction, biological LLPS is more complex, often resulting in condensates with viscoelastic, gel-like, or liquid-crystalline properties, rather than being purely viscous liquids [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Biomolecular Condensates Formed via LLPS

| Feature | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Formation Mechanism | Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) driven by multivalent interactions [1] | Provides a rapid, reversible mechanism for cellular organization without energy expenditure [1] |

| Physical State | Typically liquid-like, but can exhibit viscoelastic, gel-like, or solid-like properties [4] | Determines molecular dynamics within the condensate and impacts biochemical reaction rates [4] |

| Dynamics | Rapid exchange of components with the surrounding nucleoplasm/cytoplasm [1] | Allows condensates to respond dynamically to cellular signals and changes in the environment [4] |

| Architecture | Can form multiphase structures with layers or subcompartments [4] | Enables complex biochemical processes by creating multiple distinct microenvironments [4] |

Comparative Analysis of Experimental Methodologies

Studying biomolecular condensates requires a multidisciplinary approach, integrating cell biology, biophysics, and computational modeling. Each methodology offers distinct advantages and limitations in characterizing the formation, composition, and material properties of condensates.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Methods for Studying Biomolecular Condensates and LLPS

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Measurable Parameters | Applications in Condensate Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live-Cell Imaging | Confocal microscopy, Super-resolution microscopy (STED, STORM, Airyscan) [4] | Condensate size, count, intracellular location, and morphology [4] | Visualizing condensate formation/dissolution in response to cellular cues (e.g., stress, cell cycle) [4] |

| Biophysical Probes in Cells | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) [4] [5], Single-particle tracking [4], Single-molecule FRET [4] | Internal mobility (diffusion coefficients), exchange rates with surroundings, material state (viscosity, elasticity) [4] | Distinguishing liquid-like from solid-like condensates; measuring dynamics and internal organization [4] |

| In Vitro Reconstitution | Turbidity assays, Microscopy of purified components [5] [6] | Phase diagrams, saturation concentration, morphology of droplets [5] | Establishing the sufficiency of specific components to drive LLPS and probing biophysical drivers [5] |

| Composition Mapping | Proximity-labeling MS [7] [4], Immunoprecipitation-MS, Immunohistochemical staining [8] | Comprehensive list of condensate components (scaffolds and clients) [7] [8] | Identifying the full repertoire of proteins and RNAs within specific condensate types [7] |

| Computational Prediction | PSPredictor, FuzDrop, PScore, catGranule, DeePhase [7] | Propensity scores for protein phase separation or condensate localization [7] | Prioritizing candidate proteins for experimental studies and predicting the impact of mutations [7] |

Performance and Limitations of Methodologies

The choice of experimental method significantly influences the interpretation of a condensate's nature and function. Live-cell imaging is crucial for establishing physiological relevance, but it requires careful execution; imaging should ideally be performed in live cells at endogenous expression levels to avoid artifacts from fixation or overexpression [4]. FRAP is the gold standard for assessing condensate dynamics, where a fast recovery of fluorescence indicates a liquid-like, dynamic state, while slow or absent recovery suggests a more solid-like material property [4] [5]. However, FRAP results must be interpreted cautiously, as recovery can be influenced by factors beyond simple diffusion, such as internal binding events [4].

Computational predictors have achieved high accuracy (high AUC scores) in identifying proteins that can act as condensate "drivers" or "scaffolds" [7]. However, their performance drops significantly when tasked with predicting the specific protein segments involved in phase separation or classifying the effects of point mutations [7]. This indicates that current predictors, which largely rely on phenomenological features, do not yet fully capture the complex "molecular grammar" governing LLPS in biological contexts [7].

A key comparative finding is that the biophysical features determining a protein's localization into heteromolecular condensates differ from the features that drive homotypic phase separation. Proteins partitioning into existing condensates (e.g., NPM1-condensates) are often less hydrophobic, have higher isoelectric points, and show weaker enrichment in disordered regions compared to proteins that can drive phase separation on their own [8]. This highlights that recruitment into condensates often relies on charge-mediated protein-RNA and protein-protein interactions, not just the intrinsic phase separation propensity [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and rigorous characterization, researchers should employ a combination of the following protocols.

Protocol 1: In Vitro LLPS Assay with Purified Proteins

This protocol tests the sufficiency of a protein or protein-RNA mixture to form condensates.

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the protein of interest using standard chromatography techniques (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins). Preserve the native state by avoiding harsh denaturants [5].

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a physiologically relevant buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl). Include a reducing agent (e.g., 1 mM DTT) if needed.

- Sample Assembly: Mix the purified protein at a concentration typically ranging from 1-50 µM in the buffer. Include molecular crowding agents (e.g., 5-10% PEG or Ficoll) to mimic the intracellular environment and lower the saturation concentration [5].

- Induction and Imaging: Pipette the mixture onto a glass slide, seal with a coverslip, and immediately image using confocal microscopy. If the protein is fluorescently tagged, use appropriate laser lines and filters. Unlabeled proteins can be imaged using brightfield or differential interference contrast (DIC) to visualize droplet formation [5].

- Phase Diagram Mapping: Repeat the assay across a range of protein concentrations and environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, salt concentration) to define the phase boundary [4] [5].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Condensate Dynamics via FRAP

This protocol assesses the fluidity and dynamics of condensates in vitro or within live cells.

- Sample Preparation: Generate condensates either in vitro (as in Protocol 1) or in live cells (e.g., by expressing a fluorescently tagged protein of interest).

- Microscope Setup: Use a confocal microscope equipped with a laser suitable for photobleaching (e.g., 488 nm for GFP).

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire a few pre-bleach images of the condensate.

- Use a high-intensity laser pulse to bleach a defined region of interest (ROI) within the condensate.

- Immediately switch back to low-intensity laser scanning to monitor the fluorescence recovery into the bleached area. Acquire images at regular intervals (e.g., every second) for several minutes [4] [5].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity within the bleached ROI over time. Normalize the values to the pre-bleach intensity and to a reference unbleached area to correct for overall photobleaching. Plot the recovery curve and fit it to an exponential model to calculate the half-time of recovery and the mobile fraction [4].

Protocol 3: Mapping Composition via Proximity-Labeling Mass Spectrometry

This protocol identifies the client and scaffold proteins within a condensate in its native cellular environment.

- Cell Line Engineering: Stably express a bait protein (a known core component of the condensate) fused to a proximity-labeling enzyme, such as TurboID or APEX2 [4] [8].

- Labeling Activation: Induce the formation of the condensate (e.g., by applying cellular stress). Then, initiate the labeling reaction by adding biotin (for TurboID) or biotin-phenol and H₂O₂ (for APEX2) to the live cells for a short, defined period (typically 1-30 minutes) [8].

- Cell Lysis and Capture: Lyse the cells under conditions that preserve weak interactions. Incubate the lysate with streptavidin-coated beads to capture the biotinylated proteins.

- Protein Identification: Wash the beads stringently, digest the captured proteins with trypsin, and analyze the resulting peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [8].

- Data Analysis: Compare the abundance of identified proteins in samples expressing the bait fusion versus control samples to define a high-confidence list of condensate components.

Signaling and Assembly Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core principles of LLPS and a specific experimental workflow, generated using Graphviz DOT language.

Diagram 1: Pathways driving biomolecular condensate formation. Top: The established pathway where multivalent proteins and nucleic acids form a interacting network leading to LLPS [1]. Bottom: An emerging initiation mechanism where nonspecific metal-ion coordination induces nanoscale clustering that seeds macroscale LLPS [6].

Diagram 2: A logical workflow for a comprehensive LLPS research program, integrating computational, in vitro, and in-cellulo methods to establish the mechanism and function of a biomolecular condensate [7] [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Biomolecular Condensate Research

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phase-Separation Inducers | Molecular Crowders (PEG, Ficoll) [5], Metal Ions (Cu²⁺) [6], dsDNA scaffolds [9] | Lower the saturation concentration in vitro to induce LLPS under controlled conditions; used to probe specific assembly mechanisms. |

| Computational Predictors | PSPredictor, FuzDrop, PScore, catGranule, DeePhase [7] | Provide initial, sequence-based propensity scores for protein phase separation or condensate localization to prioritize experimental targets. |

| Fluorescent Tags | GFP, mCherry, HaloTag, SNAP-tag | Enable visualization of condensate dynamics, formation, and dissolution in live cells via fluorescence microscopy and FRAP. |

| Proximity-Labeling Enzymes | TurboID, APEX2 [4] [8] | Fused to a bait protein, these enzymes biotinylate nearby proteins in live cells, allowing subsequent pull-down and MS-based identification of condensate components. |

| LLPS Modulators | 1,6-Hexanediol, Lipoamide [5] | Small molecules that can disrupt weak, hydrophobic interactions, used to probe the material state and functional relevance of condensates. |

| Genetic Perturbation Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, siRNA, PSETAC (PROTAC) [5] | Used to knockout, knock down, or degrade target proteins to test their necessity as scaffolds for condensate formation and function. |

Biomolecular condensates are membraneless organelles that compartmentalize cellular processes in space and time. Their formation is primarily driven by a collective of key molecules and interactions, chief among them Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs), RNA, and the multivalent interactions that occur between them [10]. These components engage in a complex interplay, acting as scaffolds and clients to determine the composition, physical properties, and biological functions of condensates [4] [8] [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core drivers, synthesizing current experimental data and computational insights to outline the principles governing condensate assembly, regulation, and material properties. Understanding this molecular grammar is not only fundamental to cell biology but also critical for probing the role of condensate dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer [10].

Molecular Drivers: A Comparative Analysis

The formation and properties of biomolecular condensates are governed by the integrated contributions of specific protein domains and RNA. The table below provides a comparative summary of these key drivers.

Table 1: Key Molecular Drivers of Biomolecular Condensate Formation and Properties

| Molecular Driver | Primary Role in Condensates | Key Types of Interactions | Impact on Condensate Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) | Scaffold; mediate multivalent, transient interactions [10] | Hydrophobic, π-π, cation-π, electrostatic [10] [11] | Promotes condensate formation; tunes dynamics and viscosity [12] [11] |

| RNA-Binding Domains (RBDs) | Scaffold; mediate specific and non-specific binding [12] [11] | Electrostatic, base-specific (e.g., RRM-polyA) [11] | Recruits proteins to condensates; can biphasically promote/inhibit formation [11] |

| RNA Molecules | Scaffold or client; can nucleate or modulate condensates [10] | Electrostatic (backbone), π-interactions (bases) [10] [11] | Low concentrations promote formation; high concentrations can dissolve; increases elasticity [11] |

| Folded Oligomerization Domains | Scaffold; enables multivalency through defined interfaces [10] | Helix-helix, β-sheet, coiled-coil interactions [10] | Lowers concentration threshold for phase separation; enhances stability [10] |

The Synergistic Roles of IDRs and RBDs

Many scaffold proteins contain both IDRs and structured RNA-binding domains (RBDs), and their combined action is often necessary for proper condensate function. Research on the Xenopus oocyte RBP hnRNPAB, which contains two RBDs and an IDR, demonstrated that while each domain alone was sufficient for some enrichment in L-bodies, neither replicated the full localization or dynamic behavior of the entire protein [12]. This indicates that the two domains function synergistically. Furthermore, adding the IDR of hnRNPAB to PTBP3, an RBP that lacks an IDR, slowed the protein's diffusion within the condensate, highlighting the IDR's role in modulating internal dynamics and material properties [12].

The Dual Role of RNA in Condensate Regulation

RNA is not a passive component but an active regulator of condensate physics and composition. Its influence is concentration-dependent: at low concentrations, RNA promotes phase separation, but at high concentrations, it can inhibit the process, leading to a reentrant phase behavior [11]. Moreover, RNA significantly alters the material properties of the resulting condensates. Molecular dynamics simulations of TDP-43 condensates revealed that the presence of polyA RNA increases the system's elasticity, making it comparable in magnitude to its viscosity [11]. The sequence and chemical modifications of RNA, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A), further fine-tune its interactions with RBPs and its role in condensation [10].

Computational Prediction of Condensate Drivers

The drive to map the "granulome" has spurred the development of numerous computational predictors. A recent benchmark study evaluated 11 publicly available methods on tasks including the identification of proteins that phase separate in vitro and the prediction of residue-level segments involved in phase separation [7]. The performance of these tools varies significantly depending on the specific task.

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Select Condensate Prediction Tools [7]

| Predictor Name | Identification of Phase Separating Proteins (AUC) | Prediction of Phase Separation Regions (Performance) | Key Methodology / Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| PScore | High | Poorer | Machine learning based on pi-interaction frequency (cation-pi, pi-pi) [7] |

| FuzDrop | High | Poorer | Predicts droplet-promoting regions based on conformational entropy [7] |

| PhaSePred | High | Poorer | Meta-predictor using XGBoost model on multiple database features [7] |

| DeePhase | High | Poorer | Combines knowledge-based features with unsupervised embeddings [7] |

| LLPhyScore | High | Poorer | Uses 16 weighted features, including pi-pi and charge interactions [7] |

| catGranule | High | Poorer | Linear model based on RNA-binding, disorder, and amino acid composition [7] |

The benchmark revealed that while these predictors achieve high accuracy in identifying proteins that can phase separate (high AUC), their performance is notably poorer when tasked with predicting the specific protein segments involved in phase separation or classifying the effect of point mutations [7]. This suggests that a purely phenomenological approach may be insufficient to capture the full complexity of residue-level grammar in biological contexts.

Emerging Approaches: Protein Language Models

Beyond traditional predictors, protein language models (pLMs) like ESM2 offer a powerful, alignment-free approach to identify evolutionary constraints in IDRs. These models are trained on vast protein sequence databases and can predict the mutational tolerance of each residue in a sequence. Applying ESM2 to human proteins associated with membraneless organelles revealed that IDRs involved in phase separation contain conserved amino acids, despite the general mutational flexibility of disordered regions [13]. These conserved residues include both "sticker" residues (e.g., Tyr, Trp, Phe) and "spacer" residues (e.g., Ala, Gly, Pro), and they often form continuous, conserved motifs that are likely functional units under evolutionary selection to maintain phase separation capacity [13].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Drivers

Determining Accurate Conformational Ensembles of IDPs

Understanding IDP function requires moving beyond static structures to characterizing the ensemble of conformations they sample. A robust protocol for this involves integrating all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental data:

- MD Simulations: Long-timescale (e.g., 30 μs) all-atom MD simulations are performed using state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm36m) to generate an initial atomic-resolution conformational ensemble [14].

- Experimental Restraints: The simulation is refined against extensive experimental data, primarily from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (e.g., chemical shifts, J-couplings, residual dipolar couplings) and Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS), which provides information on ensemble-averaged structural properties [14].

- Maximum Entropy Reweighting: A fully automated maximum entropy reweighting procedure is applied to minimally adjust the statistical weights of the simulated conformations so that the averaged properties of the reweighted ensemble match the experimental data [14]. A key parameter is the target effective ensemble size, often set to preserve ~10% of the original conformations (Kish ratio K=0.10), ensuring a robust ensemble that avoids overfitting [14].

This integrative approach can yield accurate, force-field independent conformational ensembles, providing a "ground truth" for understanding IDP-driven interactions [14].

Characterizing Condensate Assembly and Properties In Cellulo

Studying condensates within a cellular context is essential for understanding their biological function. Recommended practices include:

- Imaging and Mapping Composition: To visualize large condensates (>300 nm), confocal microscopy is sufficient. For smaller clusters (20-300 nm), super-resolution techniques (e.g., STED, PALM) are required [4]. Composition can be mapped using proximity labeling followed by mass spectrometry [4].

- Probing Biophysical Properties:

- Phase Diagram Mapping: Determine the concentration thresholds for condensate formation and dissolution under different conditions [4].

- Molecular Transport: Use Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) or single-particle tracking to measure the dynamics and mobility of components within the condensate [4].

- Material Properties: Employ techniques like optical tweezers to assess viscoelasticity, distinguishing liquid-like from gel-like states [10].

A critical control is to study proteins at endogenous expression levels, as overexpression can artificially drive condensation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Condensate Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| State-of-the-Art Force Fields | Provide physical models for MD simulations. | Simulating IDP conformational landscapes (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm36m) [14]. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting Software | Integrates MD simulations with experimental data. | Determining accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs [14]. |

| Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM2) | Predicts mutational tolerance and evolutionary constraints from sequence. | Identifying conserved "sticker" and "spacer" motifs in IDRs [13]. |

| Phase Separation Predictors | Computationally identifies proteins/regions prone to phase separation. | Initial screening for potential scaffold proteins (e.g., PScore, FuzDrop) [7]. |

| Machine Learning Condensate Atlas | Predicts composition of heteromolecular condensates. | Discovering new condensate components and systems from proteomic data [8]. |

| Super-Resolution Microscopy | Visualizes sub-diffraction limit condensates in cells. | Characterizing small (<300 nm) biomolecular condensates [4]. |

| FRAP & Single-Particle Tracking | Measures dynamics and material state of condensates. | Quantifying protein mobility and condensate fluidity in live cells [4]. |

The Sticker-Spacer Model and Principles of Molecular Grammar

The spatial and temporal organization of cellular processes is fundamental to life, occurring through both membrane-bound and membrane-less compartments [15]. Biomolecular condensates, defined as concentrated non-stoichiometric assemblies of biomolecules, represent a crucial class of membrane-less organelles that form via processes bearing the hallmarks of phase transitions [15] [4]. The realization that the cell is abundantly compartmentalized into these condensates has fundamentally changed the study of biology, opening new opportunities for understanding the physics and chemistry underlying many cellular processes [4].

Among the various quantitative and qualitative models applied to understand intracellular phase transitions, the stickers-and-spacers framework offers an intuitive yet rigorous means to map biomolecular sequences and structures to the driving forces needed for higher-order assembly [16]. This model has emerged as a powerful conceptual framework for deciphering the "molecular grammar" that governs how multivalent protein and RNA molecules drive phase transitions [15]. The framework adapts principles from the field of associative polymers to biological systems, providing researchers with a unified physical language to describe the formation, maintenance, and dissolution of functionally diverse biomolecular condensates [15] [16].

Table: Core Concepts in Biomolecular Condensate Research

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Condensate | Non-stoichiometric assemblies forming via phase transitions | Organize cellular chemistry without membranes; prevent unwanted cross-talk [4] [17] |

| Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) | Demixing process forming liquid-like condensates | Initial conceptual framework for condensate assembly [15] [4] |

| Stickers-and-Spacers Model | Framework describing multivalent polymers with attractive vs. linker regions | Quantitative understanding of sequence-to-condensate relationships [15] [16] |

| Molecular Grammar | Rules connecting biomolecular sequences with emergent condensate properties | Enables predictive engineering of condensates with defined properties [17] |

The Stickers-and-Spacers Framework: Core Principles and Components

Fundamental Definitions and Physical Basis

The stickers-and-spacers model conceptualizes multivalent biomolecules as associative polymers containing two fundamental types of regions [15]. Stickers are groups that participate in specific, attractive interactions, forming reversible physical crosslinks between chains. These interactions can include hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, π-π interactions, and cation-π interactions [15] [18]. Spacers are the regions interspersed between stickers that provide scaffolds and influence the solvation volume but do not significantly drive the attractive interactions themselves [15].

This framework represents a significant advancement over traditional homopolymer theories, such as Flory-Huggins theory, which treats all monomeric units as equivalent [15]. In contrast, the stickers-and-spacers approach captures the sequence and structural heterogeneities of biological polymers, accounting for the hierarchy of anisotropic interactions encoded by the multi-way interplay among heteropolymers and the solvent [15]. The model offers remarkable flexibility in its application - stickers can be defined at different resolutions depending on the biological context, from individual amino acids in intrinsically disordered regions to entire structural domains in multidomain proteins [15].

Molecular Identities of Stickers and Spacers in Biological Systems

In intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), stickers typically correspond to Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs) that are 1-10 residues in length, while spacers are the intervening residues [15]. For folded RNA molecules, stickers may be short sequence motifs or even individual nucleotides, with non-sticker loop regions acting as spacers [15]. In structured protein domains, stickers emerge as surface patches or motifs presented by the folded structure, with other surface regions serving as spacers [15].

The model accommodates various architectural arrangements found in biological systems. In linear multivalent proteins, folded binding domains act as stickers connected by flexible disordered linkers that serve as spacers [15]. In branched multivalent systems, disordered regions create "hairy colloidal" architectures where the disordered regions (excluding SLiMs) function as spacers [15]. This flexibility in defining molecular components makes the stickers-and-spacers framework widely applicable across diverse biological contexts.

Quantitative Comparison of Sticker Strengths and Spacer Effects

Experimental Determination of Sticker Hierarchy

Systematic investigations have quantified the relative strengths of different amino acids as stickers, providing a quantitative basis for molecular grammar. Research on prion-like low complexity domains (PLCDs) has revealed that tyrosine is a stronger sticker than phenylalanine [18]. In experiments with hnRNPA1-LCD variants, replacing all phenylalanine residues with tyrosine (-12F+12Y variant) widened the two-phase regime by shifting the left arm of the binodal to lower concentrations, indicating enhanced driving forces for phase separation [18]. Conversely, replacing all tyrosine residues with phenylalanine (+7F-7Y variant) narrowed the two-phase regime, demonstrating weaker driving forces [18].

Charged residues display context-dependent behaviors. Arginine can function as an auxiliary sticker in certain contexts, while lysine typically weakens sticker-sticker interactions [18]. The net charge per residue (NCPR) emerges as a critical parameter, with increasing net charge generally destabilizing phase separation while also weakening the coupling between single-chain contraction and multi-chain interactions [18].

Table: Experimental Determination of Amino Acid Sticker Strengths

| Amino Acid | Experimental Approach | Sticker Strength/Effect | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine (Tyr) | A1-LCD variants with Tyr/Phe substitutions | Strong sticker | Widens two-phase regime; enhances driving forces [18] |

| Phenylalanine (Phe) | Same as above | Moderate sticker | Narrower two-phase regime than Tyr variants [18] |

| Arginine (Arg) | Compositional analysis of PLCD homologs | Context-dependent auxiliary sticker | Can contribute to cohesion in specific contexts [18] |

| Lysine (Lys) | Same as above | Weakens interactions | Reduces driving forces for phase separation [18] |

| Glycine (Gly) | Gly/Ser substitution variants | Non-equivalent spacer | Distinct effects from Ser despite both being spacers [18] |

| Serine (Ser) | Same as above | Non-equivalent spacer | Different spacer properties compared to Gly [18] |

Spacer Contributions to Phase Behavior

Spacers are not merely passive linkers but actively modulate phase behavior through several mechanisms. Glycine and serine residues, while both functioning as spacers, are non-equivalent in their effects on phase separation [18]. The relative glycine versus serine content represents an important determinant of the driving forces for PLCD phase separation [18].

Spacer interactions can be categorized into specific and non-specific contributions. Extensions to the stickers-and-spacers model incorporate heterogeneous, nonspecific pairwise interactions between spacers alongside specific sticker-sticker interactions [17]. While spacer interactions contribute to phase separation and co-condensation, their nonspecific nature often leads to less organized condensates compared to those driven primarily by specific sticker-sticker interactions, which form well-defined networked structures with controlled molecular composition [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Sticker-Spacer Analysis

Core Techniques for Phase Behavior Characterization

Sedimentation assays serve as a fundamental method for measuring coexisting dilute and dense phase concentrations as a function of temperature [18]. These assays determine the threshold concentration for phase separation (saturation concentration, c_sat) at specific temperatures and map coexistence curves (binodals) that define the boundaries of the two-phase regime [18].

Cloud point measurements provide estimates of critical point locations, marking the conditions where distinct phases become indistinguishable [18]. Van't Hoff analysis of temperature-dependent saturation concentrations enables extraction of apparent enthalpies and entropies of phase separation, offering insights into the thermodynamic driving forces [18].

Methodologies for Cellular Condensate Study

In cellular environments, multiple advanced techniques characterize condensate properties. Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) measures molecular transport and dynamics within condensates [4]. Single-particle tracking enables study of protein localization and diffusion characteristics [4]. Super-resolution microscopy techniques (Airyscan, structured illumination microscopy, STED, PALM) visualize smaller condensates or clusters in the 20-300 nanometer range that are inaccessible to conventional microscopy [4].

Mapping phase diagrams in cells involves genetic manipulations where researchers knock down/out endogenous copies and exogenously express proteins at different levels to determine concentration-dependence of condensate formation [4]. Live-cell imaging approaches are recommended whenever possible to avoid potential artifacts from fixation procedures [4].

Experimental Workflow for Sticker-Spacer Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Condensate Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model System Proteins | hnRNPA1-LCD and variants [18] | Prototypical PLCD for establishing sticker-spacer rules |

| Phase Separation Assays | Sedimentation assays [18] | Quantify partitioning between dilute and dense phases |

| Thermal Characterization | Cloud point measurements [18] | Determine critical point and temperature dependence |

| Cellular Imaging | FRAP, single-particle tracking [4] | Measure dynamics and material properties in cells |

| Super-resolution Microscopy | Airyscan, STED, PALM/STORM [4] | Visualize sub-diffraction limit condensates (20-300 nm) |

| Computational Models | Coarse-grained simulations [19] | Study assembly dynamics and metastable states |

| Compositional Analysis | Sequence variants with controlled substitutions [18] | Determine contributions of specific residues |

Advanced Concepts: From Metastable States to Biological Function

Kinetic Trapping and Metastable Droplets

The stickers-and-spacers framework explains why many biomolecular condensates exist as metastable multi-droplet systems rather than single, large equilibrium droplets [19]. Computational studies reveal that the kinetically arrested metastable multi-droplet state results from the interplay between two competing processes: diffusion-limited encounters between proteins, and the exhaustion of available valencies within smaller clusters [19]. When clusters form with satisfied valencies, they cannot coalesce readily, resulting in long-living droplets that persist over biologically relevant timescales [19].

This metastability has functional implications. A system-spanning network encompassing all multivalent proteins occurs only at high concentrations and large interaction valencies [19]. Under conditions favoring large clusters, simulations show a significant slow-down in the dynamics of the condensed phase, potentially resulting in loss of function [19]. Therefore, metastability represents a potential hallmark of dynamic functional droplets formed by sticker-spacer proteins, rather than a pathological state [19].

Material Properties and Regulatory Mechanisms

Biomolecular condensates exhibit diverse material states ranging from viscous fluids to gels and liquid-crystalline organizations [4]. These material properties emerge from the network structure of the condensate, transport properties within it, and the timescales of molecular contact formation and dissolution [4]. The stickers-and-spacers framework helps explain how different interaction types and patterns generate this diversity of material states.

Cells employ multiple regulatory strategies for condensate control. Scaffold-client relationships organize condensates, with scaffold molecules driving formation and recruiting client molecules that can influence phase behavior [4]. Multi-phase architectures create layered subcompartments with multiple interfaces suitable for mediating complex biochemical processes [4]. Active cellular processes regulate condensate size and location, while evolutionary pressures appear to favor low-complexity domains that suppress spurious interactions and facilitate biologically meaningful condensates [17].

The stickers-and-spacers framework provides a powerful, quantitative foundation for understanding the molecular grammar of biomolecular condensates. By mapping specific sequence features to interaction potentials and phase behavior, this model enables researchers to move beyond descriptive accounts of phase separation toward predictive design of condensate properties. The experimental methodologies and conceptual tools summarized in this guide offer a comprehensive toolkit for investigating condensate assembly, composition, and function across in vitro and cellular contexts.

As the field progresses, integrating the stickers-and-spacers framework with emerging technologies in live-cell imaging, single-molecule analysis, and computational modeling will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex language of biomolecular condensation and its implications for cellular function and dysfunction. The quantitative comparisons and experimental approaches detailed here provide a foundation for systematic investigation of how sequence-encoded information governs the formation and regulation of biomolecular condensates in health and disease.

Within the eukaryotic cell, biomolecular condensates function as membrane-less organelles that spatially and temporally organize biochemical reactions, enabling rapid cellular adaptation to fluctuating environments and intrinsic cues [10]. These condensates form primarily through a process known as liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), driven by multivalent interactions between proteins and nucleic acids [20]. Unlike classical membrane-bound organelles, biomolecular condensates exhibit dynamic assembly and disassembly, creating selective microenvironments that concentrate specific enzymes, substrates, and cofactors to regulate complex reaction networks [10]. The dysregulation of these condensates has emerged as a central pathogenic mechanism in numerous diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, highlighting their critical importance in cellular homeostasis [10] [21].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of three major cytoplasmic condensates: nucleoli, stress granules, and P-bodies. While nucleoli are nuclear condensates, they serve as a foundational model for understanding phase separation principles relevant to their cytoplasmic counterparts. Through detailed analysis of their composition, assembly mechanisms, dynamics, and functions, we aim to equip researchers with the methodological framework and experimental insights necessary to advance both basic science and translational applications in condensate biology.

Comparative Properties of Major Cellular Condensates

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Composition of Major Cellular Condensates

| Property | Nucleoli | Stress Granules (SGs) | P-bodies (PBs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Ribosome biogenesis, rRNA processing, stress signaling [10] | Storage of stalled translation pre-initiation complexes, mRNA triage [22] | mRNA decay, storage, and silencing [22] |

| Key Scaffold Proteins | Nucleophosmin (NPM1), Fibrillarin, Nucleolin [10] [21] | Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1/2 (G3BP1/2), TIA1, TIAR [23] [22] | Dep1/2, Edc3, Lsm4, Pat1b, DDX6 [22] [24] |

| Key Nucleic Acids | Ribosomal RNA (rRNA), ribosomal DNA (rDNA) [10] | Poly(A)+ mRNA, non-translating mRNAs [22] [25] | Deadenylated mRNA, mRNA targeted for decay [22] |

| Key Structural Features | Tripartite organization (FC, DFC, GC); multilayered architecture [10] | Irregular, loose granular structures; dynamic liquid-like properties [22] [4] | Compact, dense substructure; may contain fibrillar components [22] |

| Primary Triggers for Assembly | Constitutive; disassembles during mitosis [10] | Cellular stress (e.g., oxidative, heat shock, ER stress) inhibiting translation initiation [23] [22] | Constitutive presence; size/number increase with stress and translation arrest [22] [25] |

Table 2: Dynamic Properties and Regulatory Mechanisms

| Property | Nucleoli | Stress Granules (SGs) | P-bodies (PBs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material State | Viscoelastic fluid with complex fluid properties [4] | Highly dynamic, liquid-like; can solidify pathologically [23] [4] | Compact, less dynamic than SGs; gel-like properties [22] [24] |

| Disassembly Trigger | Mitotic hyperphosphorylation (e.g., of NPM1) [10] | Stress removal; requires VCP/p97 ATPase activity [23] | Restoration of normal translation; mRNA engagement in translation [22] |

| Regulatory PTMs | Phosphorylation, acetylation, arginine methylation [10] | Phosphorylation (e.g., G3BP, eIF2α), O-GlcNAcylation [23] [22] | Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, dephosphorylation [22] |

| Disease Associations | Cancer, ribosomopathies [10] [20] | Neurodegeneration (ALS/FTD), cancer [23] [10] | Autoimmune disorders, cancer, viral infection [22] [25] |

| Pharmacological Modulators | Avrainvillamide (localizer c-mod) [21] | Integrated stress response inhibitor (ISRIB, dissolver c-mod) [21] | Under investigation; specific small-molecule modulators emerging [26] |

Experimental Analysis of Condensate Dynamics

Methodologies for Condensate Characterization

The study of biomolecular condensates requires a multidisciplinary approach combining cell biology, biophysics, and computational modeling. Key methodologies for characterizing condensate assembly and properties in live cells include:

Live-Cell Imaging and Mapping Phase Diagrams: To visualize large condensates (>300 nm), wide-field or confocal microscopy is recommended. For smaller condensates or clusters (20-300 nm), super-resolution techniques such as Airyscan, structured illumination microscopy (SIM), or stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy are essential [4]. Knocking down endogenous genes and exogenously expressing the protein at different levels allows researchers to map phase diagrams and dissect the concentration-dependence of condensate formation [4].

Analysis of Material Properties: Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) is a standard technique to measure the dynamics and mobility of molecules within condensates, providing insights into their liquid-like or solid-like state [4]. Single-particle tracking can further elucidate protein localization and diffusion characteristics within these assemblies [4].

Composition Mapping: Proximity labeling approaches combined with mass spectrometry enable comprehensive mapping of the proteomic composition of condensates. Crosslinking experiments and immunoprecipitation further aid in defining constituent interactions [4] [25] [24].

Key Regulatory Pathways

Stress Granule Assembly and Disassembly Pathway: Cellular stresses such as heat shock or oxidative stress trigger the phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α, leading to global translational arrest and polysome disassembly [22]. This results in the accumulation of stalled 48S pre-initiation complexes, which then aggregate through multivalent interactions involving scaffold proteins like G3BP1 [23] [22]. G3BP1 undergoes RNA-dependent phase separation, nucleating the formation of stress granules that recruit numerous RNA-binding proteins and non-translating mRNAs [23] [10]. The disassembly of stress granules upon stress removal is an active process requiring the AAA+ ATPase VCP (valosin-containing protein) [23]. A key regulatory mechanism involves the cofactor ASPL, which couples assembly and disassembly by both promoting G3BP condensation and facilitating VCP phosphorylation and activation by UNC-51-like kinases (ULK1/2), enabling efficient extraction of G3BP and other SG components [23].

P-body Formation and mRNA Processing Pathway: P-bodies constitutively assemble around core components of the mRNA decay machinery, including the decapping enzymes Dcp1/Dcp2 and factors such as Pat1b and Edc3, which act as aggregation-prone scaffolds [22] [24]. mRNAs targeted for degradation are first deadenylated and then shuttle to P-bodies, where they can undergo decapping and 5'-to-3' degradation, storage, or silencing [22]. The material state of P-bodies is more compact and less dynamic than that of stress granules, reflecting their role in enzymatic mRNA processing [22] [24]. Under stress conditions, P-bodies frequently dock with stress granules, suggesting coordinated mRNA triage between these two condensates [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Condensate Research

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing | Endogenous tagging of condensate proteins; creation of knock-in cell lines [23] | Tagging endogenous ASPL with 3x-FLAG to study its localization [23] |

| siRNA/shRNA Knockdown | Acute depletion of specific scaffold proteins or regulators [23] | Silencing endogenous ASPL to assess its role in SG assembly [23] |

| Live-Cell Fluorescent Markers | Dynamic visualization of condensates without fixation artifacts [4] | GFP-ASPL, tdTomato-G3BP for live imaging of SG dynamics [23] |

| Super-Resolution Microscopy | Visualization of condensates and clusters below the diffraction limit (<300 nm) [4] | Airyscan, STORM, or STED to resolve small P-bodies and pre-percolation clusters [4] |

| Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) | Quantification of molecular dynamics and material properties within condensates [4] | Measuring protein mobility and exchange rates in SGs and nucleoli [4] |

| Proximity Labeling (e.g., BioID) | Unbiased mapping of condensate proteomes in near-native conditions [25] | Defining the proteomic landscape of SGs and PBs in T lymphocytes [25] |

This comparative analysis underscores that nucleoli, stress granules, and P-bodies, while unified as biomolecular condensates formed through phase separation, exhibit distinct organizational principles, dynamic properties, and functional specializations. Nucleoli serve as constitutive, multifunctional nuclear hubs for ribosome biogenesis, while stress granules and P-bodies are dynamic, stress-responsive cytoplasmic compartments that collaboratively manage mRNA fate during translation inhibition. The distinct proteomic and transcriptomic profiles of these condensates, coupled with their unique material states, enable them to perform specialized roles in cellular organization and stress adaptation.

The emerging understanding of condensate biology, particularly the molecular mechanisms governing their assembly and disassembly, opens transformative opportunities for therapeutic intervention. The development of condensate-modifying drugs (c-mods) that can dissolve, induce, or morph pathological condensates represents a promising frontier for treating complex diseases, including neurodegeneration and cancer [21] [26] [27]. As research in this field accelerates, the integration of advanced technologies such as CRISPR-based imaging, AI-driven prediction tools, and high-content screening will be crucial for translating fundamental knowledge of condensate biology into novel therapeutic strategies for patients.

Biomolecular condensates, membrane-less organelles that form via phase separation, have emerged as a fundamental mechanism for cellular organization, regulating functions from gene expression to stress response [4] [28]. The assembly and material properties of these condensates are governed by a complex interplay of weak, multivalent interactions among proteins and nucleic acids. Among these, electrostatic, cation–π, and π–π interactions constitute a critical triad of forces that determine condensate formation, stability, and composition [29] [28]. Electrostatic interactions occur between charged amino acid side chains, cation–π interactions involve the pairing of cationic residues (e.g., Arg, Lys) with the electron-rich faces of aromatic rings (e.g., Tyr, Phe), and π–π interactions arise from stacking between aromatic residues [30] [29]. Understanding the relative contributions and trade-offs between these interactions is not merely an academic exercise; it provides the foundational knowledge required to predict condensate composition, interpret disease-causing mutations, and design novel biomaterials [29] [28]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key interactions, synthesizing current experimental and computational data to equip researchers with a framework for probing condensate assembly mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Interactions

The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of the three primary interaction types, summarizing their characteristics, quantitative strengths, and roles in condensate biology.

Characteristics and Biological Roles

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Interactions in Condensate Assembly

| Interaction Type | Molecular Determinants | Range & Strength | Key Biological Functions | Susceptibility to Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | Oppositely charged residues (Asp/Glu, Lys/Arg); charge patterning [30] [8] | Long-range (5-10 Å); modulated by salt screening [30] [29] | Drives complex coacervation; recruits RNA-binding proteins; senses pH [30] [8] | High sensitivity to ionic strength, pH, and post-translational modifications [30] [29] |

| Cation–π | Cationic residues (Arg, Lys) and aromatic residues (Tyr, Phe) [29] | Short-range (~1 nm); strength ~0.2 kcal/mol in models [29] | Stabilizes condensates at high salt; common in Arg/Tyr-rich systems (e.g., FUS) [29] | Can compensate for reduced electrostatic interactions; less directly sensitive to salt [29] |

| π–π | Aromatic residues (Tyr, Phe, Trp) [29] [28] | Short-range (~1 nm); strength similar to cation–π in models [29] | Contributes to hydrophobic clustering and sticker-spacer architecture in IDPs [29] [28] | Influenced by aromatic residue content and arrangement; less specific than cation–π [29] |

Quantitative Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative data, primarily from biophysical measurements and computational simulations, reveal how these interactions jointly determine condensate stability.

Table 2: Experimental and Computational Data on Interaction Contributions

| Study System/Method | Findings on Electrostatic Interactions | Findings on Cation–π & π–π Interactions | Key Cross-Talk and Trade-Offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse-grained MD simulations of designed IDPs [29] | Stability decreases with increasing ionic strength due to charge screening. Dominant in sequences with high charged residue content and clustering. | Contribution to stability increases with higher aromatic content. Cation–π provides up to 80% greater stabilization in specific sequences. | A trade-off exists: cation–π interactions compensate for reduced electrostatic interactions at high salt concentrations. |

| Proteomics of NPM1-condensates [8] | Key driver of composition; condensate-localized proteins have higher isoelectric points (pI), suggesting positive charge drives RNA-mediated recruitment. | Not the primary focus, but hydrophobicity (related to aromaticity) also plays a significant role in determining composition. | Condensate composition is determined by both charge-mediated (protein-RNA) and hydrophobicity-mediated (protein-protein) interactions. |

| Analysis of phase-separating proteins [7] | Computational predictors (e.g., PSPredictor, LLPhyScore) successfully identify drivers using features including charge interactions. | Predictors (e.g., PScore) also use pi-interaction frequency (cation–pi, pi–pi) as features to identify phase-separating proteins. | State-of-the-art predictors phenomenologically integrate multiple interaction types but struggle with residue-level precision. |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Interactions

A combination of computational and experimental techniques is required to dissect the contribution of specific interactions.

Computational Investigation via Molecular Dynamics

Protocol: Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations [29]

- Objective: To quantify the energetic contributions and cross-talk of electrostatic, cation–π, and π–π interactions to condensate stability.

- System Design:

- Sequence Design: Create a series of 40-residue intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) sequences with varying fractions of charged residues (FCR) and aromatic residues, maintaining a net charge of zero.

- Charge Patterning: Systematically vary the charged residue clustering coefficient (κ) to test the effect of charge distribution.

- Model Setup:

- Coarse-Graining: Represent each amino acid as a single bead.

- Force Field:

- Electrostatics: Model using the Debye-Hückel potential to account for salt screening. The Debye screening length ( ( \lambdaD = 1/\kappaD ) ) is determined by the ionic strength (I) of the solvent.

- Cation–π & π–π: Model using a short-range Lennard-Jones potential with an interaction strength (ε) of ~0.2 kcal/mol and an optimal contact distance (σ) of 7 Å.

- Simulation Box: Simulate multiple copies of the sequence in an aqueous solution with periodic boundary conditions.

- Data Analysis:

- Condensate Stability: Measure the formation and lifetime of condensed assemblies.

- Interaction Analysis: Calculate the frequency and persistence of cation–π and π–π contacts compared to electrostatic interactions across different sequence designs and salt concentrations.

Experimental Validation in Cells and In Vitro

Protocol: Characterizing Condensate Assembly in Cells [4]

- Objective: To link the biophysical properties of a condensate to its biological function and test the role of specific interactions.

- Genetic Manipulation:

- Mutagenesis: Introduce point mutations that specifically perturb one type of interaction (e.g., Arg-to-Lys mutations to disrupt cation–π, or charge-neutralizing mutations to disrupt electrostatics).

- Endogenous Tagging: Study the protein at endogenous expression levels to avoid artifacts from overexpression.

- Imaging and Biophysical Analysis:

- Live-Cell Imaging: Use confocal or super-resolution microscopy (e.g., Airyscan) to visualize condensates in living cells, avoiding fixation artifacts.

- Mapping Phase Diagrams: Modulate the expression level of the protein of interest to map the concentration dependence of condensate formation.

- Measuring Material Properties:

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP): Assess the internal dynamics and viscosity of condensates by measuring the recovery of fluorescence after bleaching.

- Single-Particle Tracking: Quantify the mobility and partitioning of molecules within condensates.

- Composition Mapping:

- Use proximity labeling (e.g., BioID, APEX) followed by mass spectrometry to identify the full complement of proteins recruited to the condensate and how this composition changes upon perturbing specific interactions.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental approach to dissect interactions in condensate assembly.

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Investigating Condensate Interactions. The pathway outlines the synergistic use of computational modeling and experimental validation to dissect the roles of electrostatic, cation-π, and π-π interactions. FCR: Fraction of Charged Residues; κ: Charge Clustering Coefficient; MD: Molecular Dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Condensate Research

| Reagent / Material | Function and Utility in Condensate Research |

|---|---|

| Designed IDP Peptides [29] [28] | Simplified model systems with tunable sequences (FCR, aromatic content, charge patterning) to systematically probe specific interaction modalities. |

| 6His-Tagged Phase-Separable Proteins & Ni²⁺ [31] | Allows controlled induction of phase separation via metal coordination, useful for assembling and tuning condensates in vitro. |

| Engineered Protein Cages (e.g., mi3, Ferritin) [31] | Act as Pickering agents to stabilize condensate surfaces and control coalescence, enabling the study of size-controlled condensates. |

| Debye-Hückel Potential in MD [29] | A computational model for efficiently simulating electrostatic interactions in a salt-containing solution, crucial for quantifying salt sensitivity. |

| Lennard-Jones Potential for Aromatics [29] | A computational model for capturing the short-range dispersion forces underlying π–π and cation–π interactions in coarse-grained simulations. |

| Biological Buffers & Salts [4] [29] | To modulate ionic strength and pH in vitro, directly testing the role of electrostatic interactions and their environmental sensitivity. |

The formation and regulation of biomolecular condensates are not governed by a single molecular language but by a sophisticated dialect composed of electrostatic, cation–π, and π–π interactions. As the data demonstrates, these forces are not independent; they engage in complex trade-offs and cross-talk, allowing condensates to maintain stability across a range of cellular conditions [29]. A quintessential example is how cation–π interactions can compensate for the loss of electrostatic driving force under high salt concentrations. For researchers and drug developers, this comparative guide underscores that manipulating condensates—whether to interrogate their function, correct their dysregulation in disease, or engineer them as novel biomaterials—requires a nuanced understanding of this multifaceted interaction network. The future of the field lies in developing more refined tools to quantify these interactions at the residue level within living cells and in leveraging this knowledge for the rational design of condensates with predefined properties.

Biomolecular condensates, the membraneless organelles formed through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), have revolutionized our understanding of cellular organization. Within these dynamic structures, a fundamental organizational hierarchy exists between two key classes of molecules: scaffolds and clients. Scaffold proteins are multivalent molecules capable of driving condensate formation through their ability to form a interconnected network, while client proteins are recruited into pre-existing condensates but lack the capacity to initiate their formation [32] [33]. This scaffold-client relationship forms the architectural basis for condensate assembly, composition, and function, with scaffolds creating the structural foundation and clients contributing to functional diversity. The proper distinction between these roles is not merely semantic but fundamental to understanding how condensates form, maintain their integrity, and perform specialized biological functions across different cellular contexts.

The context-dependent nature of this hierarchy adds considerable complexity, as a protein may function as a scaffold in one cellular compartment while acting as a client in another [33]. This review provides a comparative analysis of current research methodologies, computational predictions, and experimental approaches for distinguishing scaffold and client proteins within biomolecular condensates, offering researchers a framework for investigating these dynamic organizational relationships.

Defining Molecular Roles: Scaffolds, Clients, and Dual-Affinity Linkers

Core Definitions and Functional Relationships

The terminology describing biomolecular condensate organization has evolved to precisely capture the distinct roles and relationships between constituent molecules. According to community-established definitions, a scaffold (also termed driver) refers to a biomolecule that can initiate and sustain phase separation autonomously, forming the structural backbone of the condensate [32] [33]. These molecules possess an innate capacity to form multivalent interactions that create the interconnected network giving rise to the condensate. In contrast, a client (sometimes called member) describes a molecule that partitions into pre-existing condensates but cannot initiate phase separation independently [33]. Clients typically rely on specific interactions with scaffold components for their recruitment and retention.

Beyond these core definitions, more sophisticated organizational concepts have emerged. Regulator proteins influence condensate dynamics without being physically incorporated, while dual-affinity proteins serve as molecular bridges between distinct condensates, enabling higher-order organization [34] [33]. The DEAD-box RNA helicase Pitchoune exemplifies this latter category, functioning as a molecular linker that maintains the spatial relationship between nucleoli and pericentromeric heterochromatin through its affinity for both compartments [34].

Table 1: Key Molecular Roles in Biomolecular Condensate Organization

| Role | Definition | Key Features | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold/Driver | Initiates and sustains phase separation autonomously | Multivalent, forms structural backbone | Determines condensate formation and basic architecture |

| Client/Member | Partitions into pre-existing condensates | Requires scaffolds for recruitment | Adds functional diversity and modulates condensate properties |

| Regulator | Influences condensate dynamics externally | Not permanently incorporated | Fine-tunes assembly/disassembly in response to signals |

| Dual-Affinity Linker | Connects distinct condensates | Binds components of different compartments | Enables higher-order organization between condensates |

Hierarchical Organization and Multi-Phase Architectures

The scaffold-client relationship enables the formation of complex, multi-phase architectures observed in many cellular condensates. Rather than existing as homogeneous liquids, numerous condensates display layered organization with distinct subcompartments. The nucleolus represents the quintessential example, with its clearly defined fibrillar center, dense fibrillar component, and granular subcompartments [34]. This internal architecture emerges from a hierarchy of interaction strengths between components, where scaffolds with the highest valency form the core structural elements.

Research has demonstrated that layered organizations can arise from specific interaction patterns between scaffolds and clients. In systems containing HP1, histone H1, and DNA, a layered organization emerges spontaneously, enabling cooperative DNA packaging where histone H1 first softens DNA to facilitate subsequent compaction by HP1 droplets [35]. Similarly, computational models predict that variations in interfacial surface tension between components enable the formation of ordered condensates with complex architectures [32]. These structured environments allow for functional compartmentalization within a single condensate, essentially creating "organelles within organelles" that can host biochemically incompatible processes in close proximity.

Computational Prediction Methods: Performance and Limitations

Benchmarking Computational Predictors

The rapid expansion of knowledge about biomolecular condensates has spurred the development of numerous computational tools to predict protein phase separation behavior and classify scaffolds and clients. Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated these predictors across different tasks, including identification of phase-separating proteins, distinction between scaffolds and clients, and prediction of mutation effects. As shown in Table 2, these tools employ diverse algorithms and training datasets, leading to variations in their performance characteristics [7].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Computational Predictors for Scaffold and Client Identification

| Predictor | Algorithm | Training Basis | Scaffold Identification (AUC) | Client Identification (AUC) | Residue-Level Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PScore | Machine learning (pi-interactions) | PDB structures | 0.89 | 0.85 | Limited |

| FuzDrop | Conformational entropy | In vitro/vivo annotated proteins | 0.91 | 0.87 | Moderate |

| catGranule | Linear model | 120 yeast granule proteins | 0.84 | 0.82 | Limited |

| PSAP | Random forest | 90 human phase-separating proteins | 0.92 | 0.88 | Limited |

| PhaSePred | XGBoost tree | 658 validated proteins | 0.90 | 0.86 | Limited |

| DeePhase | Word2vec + knowledge features | Multiple databases | 0.88 | 0.84 | Moderate |

| LLPhyScore | Weighted feature model | Validated proteins | 0.87 | 0.83 | Limited |

Overall, predictors achieve high accuracy (AUC > 0.85) in distinguishing scaffold proteins from non-phase-separating proteins and show strong performance in identifying proteins capable of phase separating in vitro [7]. This robust performance stems from the ability of these algorithms to capture key molecular features associated with phase separation, such as intrinsic disorder, multivalency, and specific interaction motifs. However, their performance significantly decreases when applied to more nuanced tasks, such as predicting specific protein segments involved in phase separation or classifying the impact of amino acid substitutions [7]. This performance gap highlights a fundamental limitation in the current phenomenological approach adopted by most predictors, which often prioritize correlative features over mechanistic understanding.

Dataset Challenges and Standardization Efforts

The reliability of computational predictors depends heavily on the quality and composition of their training datasets. Significant challenges exist in curating balanced datasets for biomolecular condensate research, particularly regarding negative examples (proteins not involved in LLPS) and clear differentiation between scaffold and client proteins [33]. Current LLPS databases employ divergent curation criteria and evidence standards, leading to interoperability issues and potential annotation inconsistencies.

Recent efforts have addressed these challenges through integrated biocuration protocols that apply standardized filters across multiple databases (PhaSePro, PhaSepDB, LLPSDB, CD-CODE, and DrLLPS) [33]. These approaches generate high-confidence datasets by requiring experimental evidence for classification and implementing cross-database validation. For negative datasets, researchers have developed standardized collections that include both globular proteins (from PDB) and disordered proteins (from DisProt) not associated with LLPS, providing more realistic benchmarks for predictor training and evaluation [33]. These curated resources represent a significant advancement toward more reliable predictive models that can accurately distinguish between scaffolds and clients across different biological contexts.

Experimental Approaches for Distinguishing Scaffolds and Clients

Core Methodologies for Characterizing Condensate Components

Experimental distinction between scaffolds and clients requires integrated approaches that assess both the capacity for autonomous condensate formation and the dependency relationships between components. A comprehensive experimental framework typically begins with cellular observations and progresses through increasingly reductionist in vitro reconstitutions.

Cellular Localization and Dynamics: Initial characterization begins with visualizing protein localization in live cells using fluorescently tagged proteins expressed at endogenous levels. Super-resolution techniques (Airyscan, STED, STORM) enable visualization of small condensates or clusters below the diffraction limit [4]. Techniques like fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) provide insights into material properties and dynamics, with scaffolds typically displaying slower recovery than clients due to their network-forming capacity [4].

Perturbation Experiments: Genetic or chemical perturbations that disrupt potential scaffold proteins provide critical evidence for functional classification. Scaffold disruption typically causes complete condensate dissolution, while client perturbation may only alter composition without preventing formation [4] [34]. For example, elimination of nucleolar scaffolds by removing ribosomal RNA genes causes complete nucleolar disassembly, while simultaneously disrupting the organization of associated pericentromeric heterochromatin [34].

In Vitro Reconstitution: Reductionist approaches using purified components test the minimal requirements for phase separation. A protein's ability to form droplets in defined conditions without binding partners provides strong evidence for scaffold classification [7] [33]. These experiments allow systematic control over parameters such as concentration, pH, ionic strength, and crowding agents to define phase boundaries.

Client Recruitment Assays: Client proteins can be tested for their ability to partition into condensates formed by putative scaffolds. The Banani et al. system using polySUMO/polySIM scaffold proteins with monovalent GFP-labelled clients exemplifies this approach, demonstrating how client recruitment depends on scaffold stoichiometry and interaction availability [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: CAPRIN1-FUS RRM System

A recent investigation of the CAPRIN1-FUS RRM system provides an exemplary protocol for distinguishing scaffold-client relationships and their functional consequences [36]. This study illustrates how scaffold-client interactions can suppress protein aggregation, challenging the conventional view that condensates primarily promote aggregation.

Experimental System and Objectives: The research examined condensates scaffolded by the C-terminal disordered region of CAPRIN1 (scaffold) and their effect on the Fused in Sarcoma RNA Recognition Motif (FUS RRM) domain (client). The primary objective was to determine how scaffold-client interactions influence client stability and aggregation propensity [36].

Methodological Workflow:

- Condensate Formation: CAPRIN1's C-terminal disordered region was expressed and purified for in vitro condensate formation under physiological buffer conditions.

- Client Partitioning: FUS RRM was added to pre-formed CAPRIN1 condensates, and partitioning was quantified using fluorescence microscopy.

- Aggregation Monitoring: FUS RRM aggregation kinetics were monitored in the presence and absence of CAPRIN1 condensates using thioflavin T staining and turbidity measurements.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Comparative NMR studies characterized FUS RRM conformational changes outside and within CAPRIN1 condensates, identifying regions of transient intermolecular contacts.

- Intermolecular NOE: Nuclear Overhauser effect measurements mapped specific interaction surfaces between CAPRIN1 and unfolded FUS RRM protomers.

Key Findings: Despite concentrating FUS RRM twofold and significantly unfolding the domain, CAPRIN1 condensates attenuated FUS RRM aggregation. NMR identified specific hydrophobic regions in FUS RRM (I287-I308 and G335-A369) that drive aggregation, while intermolecular NOE revealed that CAPRIN1 interacts extensively with unfolded FUS RRM, particularly at sequences 287IFVQ290, 296VTIES300, 322INLY325, and 351IDWFDG356 [36]. These interactions collectively outcompeted homotypic contacts between unfolded FUS RRM clients that would otherwise drive aggregation.

Interpretation: In this system, CAPRIN1 functions as a protective scaffold that engages aggregation-prone regions of the client protein, effectively shielding them from self-association. This demonstrates how scaffold-client relationships can maintain protein homeostasis rather than promote pathological aggregation, expanding our understanding of the functional consequences of condensate organization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Scaffold-Client Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Tags | GFP, RFP, mCherry | Live-cell imaging | Protein localization and dynamics visualization |

| Phase Separation Markers | Polr1E (FC), Fibrillarin (DFC), HP1a (PCH) | Condensate identification | Specific compartment labeling |

| Predictive Algorithms | FuzDrop, PScore, catGranule | Computational screening | Initial scaffold/client prediction |

| Databases | PhaSePro, DrLLPS, LLPSDB | Data mining and benchmarking | Curated experimental evidence |

| Model Scaffolds | PolySUMO/polySIM, NPM1, CAPRIN1 | In vitro reconstitution | Defined system establishment |

| Analytical Tools | NMR spectroscopy, FRAP, Intermolecular NOE | Molecular interaction mapping | Residue-level interaction characterization |

The distinction between scaffold and client proteins represents more than just a classification exercise—it provides fundamental insights into the organizational principles of cellular organization. While computational predictors offer valuable screening tools, their current limitations in residue-level predictions and context-dependence necessitate experimental validation through integrated approaches. The field has progressed from simple binary classifications toward understanding sophisticated hierarchies of interactions that govern multi-phase organization.

Future research will likely focus on developing more mechanistic predictors that move beyond phenomenological correlations, expanding standardized datasets that capture contextual variability, and creating dynamic models that simulate how scaffold-client relationships evolve under different cellular conditions. As our understanding of these hierarchical relationships deepens, so too will our ability to manipulate condensates for therapeutic purposes, particularly in diseases where disrupted phase separation contributes to pathology. The continued integration of computational, biophysical, and cell biological approaches remains essential for unraveling the complex hierarchy of biomolecular condensates.

Tools and Techniques for Condensate Analysis and Manipulation

Biomolecular condensates, the membrane-less organelles that organize cellular biochemistry, represent a frontier in modern cell biology and drug development. Their study demands microscopy techniques capable of capturing dynamic processes at nanoscale resolutions without disturbing their delicate physical states. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate imaging method is crucial, as the material properties and nanoscale organization of condensates directly influence their biological function and relevance to diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [4]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of advanced microscopy techniques—holographic, super-resolution, and fluorescence microscopy—evaluating their performance, applications, and experimental requirements for protein condensate research.

Technical Comparison of Microscopy Modalities

The following table summarizes the core performance metrics of the primary advanced microscopy techniques used in condensate studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Advanced Microscopy Techniques

| Technique | Lateral Resolution | Axial Resolution | Live-Cell Suitability | Label Requirement | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wide-Field/Deconvolution (WFD) [37] | ~200-300 nm [38] | ~500-800 nm [38] | High | Fluorescent Labels | High photon collection efficiency; suitable for live-cell 3D imaging [37]. | Limited resolution; background from out-of-focus light [37]. |

| Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) [38] | 90-130 nm | 250-400 nm (3D-SIM) [38] | Intermediate to High [38] | Fluorescent Labels | High speed; multi-color imaging (3-4 colors) [38]. | Susceptible to reconstruction artifacts [38]. |

| STED Microscopy [38] | ~50 nm (2D STED) [38] | ~100 nm (3D STED) [38] | Variable (tuneable) [38] | Fluorescent Labels | Tunable resolution in exchange for increased illumination [38]. | High photobleaching and phototoxicity [38]. |

| SMLM (PALM/dSTORM) [38] | ≥ 2x localization precision [38] | Lower precision than lateral [38] | Very Low (fixed cells) [38] | Fluorescent Labels | Highest localization precision (10-20 nm); single-molecule data [38]. | High dye restrictions; very slow temporal resolution [38]. |