Bioinorganic Chemistry in Biological Systems: From Fundamental Metals to Advanced Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of bioinorganic chemistry, detailing the critical roles of metal ions in biological processes and their burgeoning applications in medicine.

Bioinorganic Chemistry in Biological Systems: From Fundamental Metals to Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of bioinorganic chemistry, detailing the critical roles of metal ions in biological processes and their burgeoning applications in medicine. It covers foundational principles of metalloenzyme function and metal homeostasis, progresses to methodological advances in drug design such as ruthenium and gold-based anticancer agents, and addresses key challenges in optimization and analytical validation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes foundational knowledge with current research trends and future directions in diagnostic and therapeutic development.

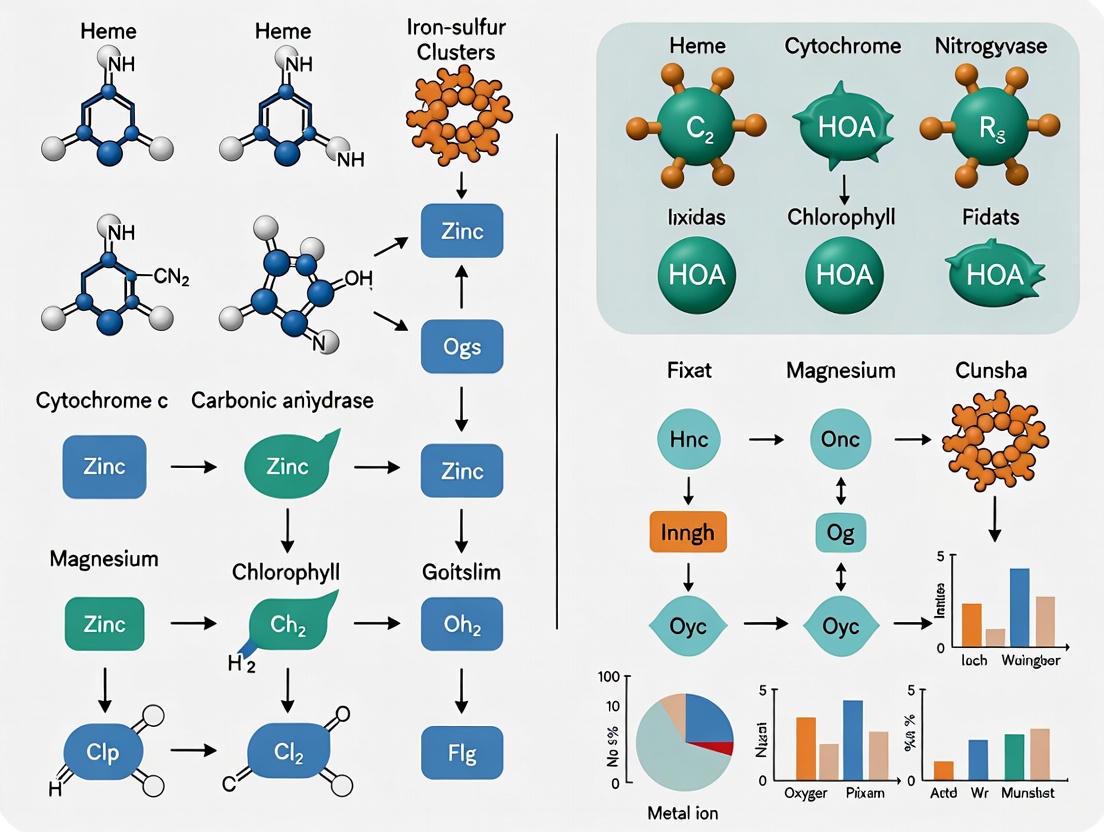

The Essential Roles of Metals in Biology: From Basic Elements to Life-Sustaining Functions

Bioinorganic chemistry is a field that encompasses the intersection between inorganic chemistry and biochemistry, focusing on the structures and biological functions of inorganic biological substances, such as metals [1] [2]. This discipline investigates the roles of naturally occurring inorganic elements in biology and explores the application of non-naturally occurring metals in biological systems as probes and drugs [2]. The traditional distinction between organic chemistry as the "chemistry of life" and inorganic chemistry as "non-living" chemistry is overly simplistic, as fundamental biological processes crucial for life are driven by inorganic elements and reactions [3]. A prime example is the reduction of oxygen to water, a reaction essential for aerobic metabolism that is catalyzed by metalloproteins in the electron transport chain [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Biological Functions of Inorganic Elements

| Biological Function | Description | Key Elements/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Transfer | Facilitating cellular respiration and photosynthesis through redox reactions | Iron-Sulfur clusters, Copper centers in Cytochrome C Oxidase [2] [3] |

| Oxygen Activation & Transfer | Binding, activating, and transporting molecular oxygen | Iron in Hemoglobin; Copper in Hemocyanin [2] |

| Structural Stabilization | Providing structural integrity to proteins and biomolecules | Zinc fingers in transcription factors [2] |

| Hydrolytic Catalysis | Catalyzing the breakdown of molecules via hydrolysis | Zinc in Carbonic Anhydrase; Nickel in Urease [2] [3] |

| Protection from Oxidative Stress | Defending against reactive oxygen species | Copper/Zinc in Superoxide Dismutase (SOD1) [2] [3] |

Metal Binding and Coordination in Biological Systems

The binding of metal ions to enzymes and proteins typically occurs through specific amino acid ligands, creating a coordination environment that dictates the metal's reactivity [2]. Common amino acid ligands include histidine (via nitrogen), cysteine (via sulfur), aspartate, and glutamate (both via oxygen) [2]. While this is the most prevalent binding mode, some biological systems employ alternative strategies, such as using hydrogen bonding schemes to position a solvated inorganic ion or incorporating exogenous (non-amino acid) ligands to help stabilize the metal [2]. These coordination complexes form the active sites of metalloenzymes, enabling them to perform specialized chemical tasks that organic functional groups alone cannot achieve efficiently.

Key Experimental Methodologies in Bioinorganic Chemistry

Advanced spectroscopic and analytical techniques are essential for probing the structure and function of inorganic elements in biological systems. These methods provide insights into metal coordination environments, oxidation states, and magnetic properties, which are crucial for understanding mechanism.

Spectroscopic and Magnetic Techniques

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy is a particularly powerful tool for studying paramagnetic metal centers, which are common in bioinorganic systems [2]. EPR detects unpaired electrons in a sample by their absorption of energy from microwave irradiation when placed in a strong magnetic field [2]. The technique is highly sensitive, capable of detecting high-spin ferric ions in the µM range, and can establish the stoichiometries of complex mixtures of paramagnets [2]. EPR spectra are characterized by four main parameters: intensity, linewidth, g-value (which defines position), and multiplet structure resulting from hyperfine interactions with nuclear spins [2]. For more detailed ligand identification, advanced EPR techniques such as Electron-Nuclear Double Resonance spectroscopy (ENDOR) and Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) are employed [2].

Other crucial techniques include magnetic moment measurements and their temperature dependence, which are sensitive probes for identifying polynuclear metal clusters [4]. Mössbauer spectroscopy is specifically valuable for studying iron-containing proteins and model compounds, providing information on oxidation state, spin state, and coordination environment [4]. Vibrational spectroscopy offers insights into metal-ligand bonding, while X-ray diffraction remains the definitive method for determining three-dimensional atomic structures of metalloproteins and their synthetic analogues [4].

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Metalloprotein Characterization

| Technique | Key Applications | Structural & Electronic Information |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Detection and characterization of paramagnetic centers (V, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Mo, W) [2] | Oxidation state, coordination geometry, hyperfine interactions with ligands [2] |

| Magnetic Susceptibility | Studying polynuclear metal clusters, interaction between metal centers [4] | Magnetic moment, exchange coupling between metal ions [4] |

| Mössbauer Spectroscopy | Specifically for iron-containing systems [4] | Oxidation state, spin state, coordination symmetry [4] |

| X-ray Crystallography | Determining atomic-level structure of metalloproteins and model complexes [4] | Precise bond lengths and angles, overall protein fold, active site geometry [4] |

| Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy | Probing d-d transitions and charge-transfer bands [4] | Coordination geometry, oxidation state, ligand field effects [4] |

Experimental Protocol: EPR Spectroscopy of Metalloproteins

Principle: EPR spectroscopy detects species with unpaired electrons by measuring their absorption of microwave radiation in an applied magnetic field. The resonance condition occurs when the energy of the microwave photons matches the energy splitting between electron spin states.

Materials:

- Purified metalloprotein sample in appropriate buffer (≥ 100 µL)

- EPR tube (high-purity quartz for X-band)

- Liquid helium or nitrogen cryostat

- X-band EPR spectrometer (∼ 9-10 GHz)

- Redox agents for controlled potential experiments (if needed)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate protein to >100 µM in metal center. Use buffer systems that do not interfere (avoid high salt or glycerol unless necessary). For frozen solutions, add 15-20% glycerol as cryoprotectant.

- Experimental Conditions:

- Temperature: Typically 10-50 K for metalloproteins to slow relaxation

- Microwave Power: 0.1-20 mW (avoid saturation)

- Modulation Amplitude: 0.1-1.0 mT (optimize for resolution vs. intensity)

- Field Scan: 0-1.0 T (center field depends on metal ion)

- Data Collection:

- Record first derivative spectrum

- Perform power saturation studies to determine relaxation properties

- Collect spectra at multiple temperatures (10K, 30K, 50K, 77K)

- Data Analysis:

- Determine g-values from field position relative to standard

- Analyze hyperfine splitting for nuclear spin interaction

- Simulate spectra to extract spin Hamiltonian parameters

Interpretation: The g-tensor values provide information about the metal center's electronic structure. Axial or rhombic symmetry can be identified from the g-tensor pattern. Hyperfine splitting (interaction with nuclear spin) identifies specific metal isotopes and their ligand environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioinorganic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts (e.g., FeCl₃, CuSO₄, ZnCl₂) | Synthesis of model complexes; metal reconstitution of apoproteins [2] |

| Metal Chelators (e.g., EDTA, TPEN) | Selective removal of metals from proteins; control of metal bioavailability [2] |

| Siderophores (e.g., Enterobactin, Ferrioxamine) | Study of bacterial iron acquisition; models for metal transport [3] |

| Redox Agents (e.g., Dithionite, Ascorbate, Ferricyanide) | Controlled manipulation of metal center oxidation states for spectroscopic studies [2] |

| Stable Isotopes (⁵⁷Fe, ⁶⁷Zn, ⁶⁵Cu) | Enhanced NMR, Mössbauer, and EPR studies; tracing metal assimilation pathways [2] |

| Crystallization Screens | Growing diffraction-quality crystals of metalloproteins for X-ray structure determination [4] |

| Phosphonate-Based Probes | Monitoring metal ions (e.g., copper) in biological systems like C. elegans [1] |

Current Research Frontiers and Applications

Medical Applications and Metallodrugs

The discovery of Cisplatin by Rosenberg in 1965 marked a revolutionary advancement in bioinorganic chemistry, establishing the field of metallo-drugs [2]. Cisplatin and its derivatives represent for cancer treatment what Penicillin represented for infectious diseases [2]. Current research focuses on developing tumor-selective platinum drugs that can be administered at lower doses with fewer side effects and higher therapeutic index [2]. Drug targeting and delivery strategies are categorized into active and passive approaches. Active targeting relies on specific molecular interactions between the drug and cell or tissue elements, while passive targeting exploits the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect occurring in tumor tissues [2]. These approaches aim to create "magic bullets" that deliver metal-based therapeutics specifically to diseased cells.

Emerging Biological Roles of Uncommon Elements

Research continues to reveal unexpected biological roles for elements previously considered irrelevant to biology. Lanthanides have been identified as biologically essential metals, crucial in the active sites of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzymes in methylotrophic bacteria [1]. Recent studies demonstrate that trivalent actinide ions, including actinium, americium, curium, berkelium, and californium, can substitute for lanthanides in ADHs and support bacterial growth [1]. This expansion of the periodic table's biologically relevant elements opens new avenues for understanding metal utilization in extreme environments and developing novel biocatalysts. Other elements like aluminum, silicon, and strontium are also receiving increased attention for their potential roles in biological systems, particularly in bone growth, crop development, and detoxification pathways [2].

Bioinorganic chemistry provides fundamental insights into how inorganic elements enable essential biological processes, from electron transfer and oxygen transport to catalytic transformations in metalloenzymes. The field has expanded significantly from studying natural systems to designing innovative therapeutic agents, with Cisplatin representing a landmark achievement in metallodrug development [2]. Current research continues to push boundaries, exploring uncommon biological elements [1], developing sophisticated drug targeting strategies [2], and employing advanced spectroscopic techniques to elucidate metal center structure and function [2] [4]. As analytical methods become more powerful and our understanding of metal homeostasis in biological systems deepens, bioinorganic chemistry will continue to bridge the periodic table with biological function, offering new solutions to challenges in medicine, energy, and environmental science.

Metal ions are fundamental components in bioinorganic chemistry, serving as critical cofactors for a vast array of proteins and enzymes essential to life. These elements confer structural stability and catalytic power to biological macromolecules, enabling them to perform chemical transformations that are often unattainable by organic functional groups alone [5] [6]. Approximately half of all enzymes require metal ions for their activity, highlighting their indispensable role in biological systems [5]. The field of bioinorganic chemistry seeks to understand these roles at a molecular level, investigating how metal-protein interactions influence biological function and how disruptions in metal homeostasis contribute to disease pathology [6].

This review examines the essential metal ions in biological systems, focusing on their structural and catalytic functions within metalloproteins and metalloenzymes. We explore the fundamental principles governing metal-protein interactions, survey advanced analytical techniques for studying these complexes, and discuss the biomedical implications of metal dysregulation. Furthermore, we examine emerging approaches in metalloprotein design and engineering that promise to advance both our fundamental understanding and therapeutic applications.

Essential Metal Ions in Biological Systems

Classification and Biological Significance

Twenty elements are currently considered essential for proper human physiological functioning, with metals constituting half of these essential elements [5]. These include four main group metals—sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca)—and six d-block transition metals—manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and molybdenum (Mo) [5]. These essential metals participate in diverse cellular processes, with particularly critical functions in the central nervous system [5].

Cells have evolved sophisticated metallo-regulatory mechanisms to maintain metal ion homeostasis, which is crucial for proper cellular function [5]. This homeostasis is especially critical for redox-active transition metals like iron and copper, which can participate in electron transfer reactions and, when improperly regulated, can catalyze the formation of damaging reactive oxygen species via Fenton chemistry [5]. Both deficiency and excess of essential metals can lead to various pathological states, including neurological disorders (Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases), mental health disorders, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes [5].

Table 1: Essential Metal Ions in Biological Systems

| Metal Ion | Primary Biological Roles | Key Metalloproteins/Enzymes | Consequences of Dyshomeostasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na⁺, K⁺ | Charge carriers, osmotic balance, nerve impulse transmission | Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase, ion channels | Neuromuscular dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmias |

| Mg²⁺ | Enzyme cofactor, structural stabilization | ATP-dependent enzymes, ribozymes, DNA polymerases | Metabolic disorders, muscle weakness |

| Ca²⁺ | Cellular signaling, structural role | Calmodulin, troponin C, bone mineral matrix | Neurological disorders, skeletal abnormalities |

| Mn²⁺ | Redox catalysis, antioxidant defense | Mn-SOD, arginase, photosystem II | Neurological disorders, mitochondrial dysfunction |

| Fe²⁺/³⁺ | Oxygen transport, electron transfer, catalysis | Hemoglobin, cytochromes, iron-sulfur proteins | Anemia, hemochromatosis, neurodegenerative diseases |

| Co²⁺ | Enzyme cofactor | Vitamin B₁₂-dependent enzymes | Pernicious anemia, neurological symptoms |

| Cu⁺/²⁺ | Electron transfer, oxidase activity | Cytochrome c oxidase, Cu,Zn-SOD, tyrosinase | Wilson's disease, Menkes disease, neurodegenerative disorders |

| Zn²⁺ | Structural, catalytic, gene regulation | Zinc fingers, carbonic anhydrase, alcohol dehydrogenase | Immune dysfunction, growth retardation, neurological effects |

| Mo | Oxotransferase activity | Xanthine oxidase, sulfite oxidase | Neurological symptoms, developmental defects |

Metal Ion Coordination Chemistry in Proteins

The biological functionality of metal ions in proteins is dictated by their coordination chemistry, including coordination number, geometry, and ligand donor atoms [7]. Metal ions in metalloproteins typically coordinate with heteroatoms from amino acid side chains (e.g., histidine imidazole, cysteine thiolate, glutamate/aspartate carboxylate) or prosthetic groups (e.g., heme, chlorophyll) [8]. The protein matrix precisely positions these ligands to create specific coordination environments that fine-tune the metal's chemical properties for its biological function [8] [7].

The metal coordination sphere profoundly influences catalytic efficiency, as demonstrated in studies of human carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) [7]. Native zinc-CA II exhibits tetrahedral coordination with three histidine residues and a water molecule, optimal for its catalytic function [7]. Metal substitutions that alter this coordination geometry dramatically reduce catalytic activity: Co²⁺-CA II (tetrahedral to octahedral conversion) retains ~50% activity, Ni²⁺-CA II (octahedral) retains only ~2%, and Cu²⁺-CA II (trigonal bipyramidal) is completely inactive [7]. These findings highlight how metal coordination geometry directly modulates catalytic processes including substrate binding, conversion to product, and product release [7].

Structural Roles of Metal Ions in Proteins

Principles of Structural Metal Binding Sites

Metal ions serve crucial structural roles in proteins by stabilizing specific folds and conformations that are essential for function. Structural metal binding sites typically employ metal ions with well-defined, stable coordination geometries that provide cross-linking points within or between protein chains [8]. These metal-ion interactions can nucleate protein folding, stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures, and mediate protein-protein interactions [8].

The stability imparted by structural metal sites often derives from the favorable thermodynamics of metal-ligand bond formation, which can compensate for the entropic cost of protein folding [8]. Unlike catalytic sites that often undergo coordination changes during turnover, structural metal sites generally maintain stable coordination geometries throughout their functional cycle [8].

Examples of Structural Metalloproteins

A classic example of structural metal sites is found in zinc finger proteins, where zinc ions are tetrahedrally coordinated by cysteine and/or histidine residues to create stable protein domains that recognize specific DNA sequences [6]. These domains rely on zinc for structural integrity rather than direct catalytic activity [6].

Another illustrative case comes from de novo protein design studies, where researchers have engineered high-affinity thiolate sites that bind heavy metals like mercury to stabilize three-stranded coiled coils [8]. In these designed proteins, the structural metal site (HgS₃) provides sufficient thermodynamic stability to allow the incorporation of a separate catalytic zinc site, demonstrating how structural metal binding can enable the creation of functional metalloenzymes [8].

Catalytic Roles of Metal Ions in Enzymes

Mechanisms of Metal-Ion Catalysis

Metalloenzymes employ metal ions to catalyze some of the most challenging chemical transformations in nature, including water oxidation, nitrogen fixation, and methane oxidation [8]. Metal ions facilitate catalysis through several mechanisms:

Lewis Acid Catalysis: Metal ions act as electron pair acceptors, polarizing substrates and making them more susceptible to nucleophilic attack [7]. In carbonic anhydrase, the zinc ion lowers the pKₐ of bound water from ~10 to ~7, generating a nucleophilic hydroxide ion at physiological pH [7].

Redox Catalysis: Transition metals with multiple accessible oxidation states (e.g., Fe, Cu, Mn) facilitate electron transfer reactions [5]. These metals are essential in enzymes like cytochromes, superoxide dismutases, and catalases [5].

Electrostatic Stabilization: Metal ions stabilize charged transition states and intermediates during catalysis [7]. In CA II, metal ions exert long-range (~10 Å) electrostatic effects that restructure water networks in the active site, affecting both product displacement and proton transfer [7].

Substrate Orientation and Proximity Effects: By binding and positioning substrates in optimal orientations, metal ions facilitate precise chemical transformations with remarkable regio- and stereoselectivity [8].

Case Study: Carbonic Anhydrase Catalysis

Carbonic anhydrase provides an excellent model system for understanding metalloenzyme catalysis [7]. The catalytic cycle of zinc-CA II involves multiple steps:

- The zinc-bound water molecule deprotonates to form a zinc-hydroxide at physiological pH [7].

- CO₂ enters the active site and positions itself for nucleophilic attack [7].

- The zinc-bound hydroxide attacks CO₂, forming bicarbonate coordinated to zinc [7].

- Bicarbonate is displaced by a water molecule, regenerating the initial state [7].

- The proton generated during the first step is transferred to buffer molecules via a proton shuttle residue [7].

This mechanism enables CA II to achieve some of the highest catalytic rates known, approaching the diffusion limit [7]. Studies with metal-substituted CA II variants have revealed how metal coordination geometry directly influences each step of this catalytic cycle [7].

Diagram 1: Catalytic cycle of carbonic anhydrase showing the zinc-centered mechanism for CO₂ hydration.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Metalloprotein Studies

Spectroscopic and Crystallographic Methods

Understanding metal ion function in biological systems requires sophisticated analytical approaches that can probe metal coordination environments, oxidation states, and dynamics [6]. Several powerful techniques are employed:

X-ray crystallography provides atomic-resolution structures of metalloproteins, revealing metal coordination geometry and active site architecture [7]. Advanced techniques like serial synchrotron and XFEL crystallography enable studies of metalloprotein catalysis under functional conditions [6]. Neutron protein crystallography offers unique insights into protonation states and hydrogen bonding networks around metal sites [6].

Spectroscopic methods including electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (EXAFS, XANES), and various magnetic resonance techniques provide complementary information about electronic structure, oxidation states, and ligand environments [6] [7]. Heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy is particularly valuable for studying metal-protein interactions and dynamics in solution [6].

Quantitative Elemental Imaging

Recent advances in label-free elemental imaging have revolutionized our ability to visualize and quantify metals in biological systems with subcellular resolution [9]. These techniques include:

X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) utilizes synchrotron radiation to map element distribution in biological samples, detecting multiple elements simultaneously with high sensitivity [9]. XFM has revealed zinc fluctuations during mammalian oocyte maturation and fertilization, including the discovery of "zinc sparks" - dramatic zinc exocytosis events essential for embryonic development [9].

Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) provides highly sensitive elemental and isotopic analysis, enabling creation of quantitative metal maps in tissues [9]. This technique has been applied to diagnose metal overload disorders like Wilson's disease by measuring copper accumulation in liver biopsies [9].

Nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (nanoSIMS) offers exceptional spatial resolution for subcellular metal localization studies, such as mapping manganese distribution in oyster oocytes [9].

Table 2: Advanced Techniques for Metalloprotein Analysis

| Technique | Information Obtained | Spatial Resolution | Applications in Metalloprotein Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic structure, metal coordination geometry | ~1.0 Å | Determining active site structures of metalloenzymes [7] |

| Cryo-electron Tomography | 3D cellular architecture, in situ protein structures | ~3-10 Å (cellular context) | Visualizing metalloproteins in native cellular environments [6] |

| X-ray Fluorescence Microscopy (XFM) | Elemental distribution, quantification | ~30 nm | Mapping metal localization in cells and tissues [9] |

| Laser Ablation ICP-MS | Elemental and isotopic quantification | ~1-10 μm | Quantitative metal bioimaging for disease diagnosis [9] |

| EPR Spectroscopy | Oxidation state, coordination symmetry, dynamics | N/A | Characterizing paramagnetic metal centers in proteins [7] |

| NanoSIMS | Elemental and isotopic mapping | ~50 nm | Subcellular metal localization studies [9] |

Metalloprotein Design and Engineering

Approaches to Metalloprotein Design

The design and engineering of metalloproteins represents a powerful approach for understanding structure-function relationships and creating novel biocatalysts [8]. Two primary strategies are employed:

Protein redesign involves introducing metal-binding sites into existing protein scaffolds or modifying native metal sites to alter their properties [8]. This approach leverages the inherent stability of natural protein folds while engineering new functions [8].

De novo design aims to construct metalloproteins "from scratch" by designing primary sequences that fold into predicted structures containing desired metal-binding sites [8]. This approach tests our fundamental understanding of metalloprotein folding and function, eliminating complexities inherent in natural systems [8].

Functional Designed Metalloproteins

Significant progress has been made in designing functional metalloproteins with catalytic activities approaching those of natural enzymes [8]. One successful example combines a structural mercury-binding site (HgS₃) that stabilizes a three-stranded coiled coil with a separate catalytic zinc site (ZnN₃O) that mimics carbonic anhydrase activity [8]. This designed metalloprotein demonstrates that attaining proper first-coordination geometry can lead to significant catalytic activity, largely independent of the secondary structure of the surrounding protein environment [8].

Such designed metalloproteins not only advance our understanding of natural systems but also hold promise for creating novel biocatalysts for industrial processes, potentially offering cheaper, more stable, and environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional catalysts [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Metalloprotein Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Metalloproteins | Structural and functional studies | Requires optimization of metal incorporation during expression and purification |

| Metal Chelators | Controlling metal availability in experiments | Selectivity and affinity for specific metal ions must be considered |

| X-ray Crystallography Reagents | Structural determination of metalloproteins | Cryoprotectants often needed for cryocooling; may require anaerobic handling for oxygen-sensitive metals |

| Spectroscopic Probes | Monitoring metal binding and reactivity | Includes EPR spin labels, fluorescent zinc probes, etc. |

| LA-ICP-MS Standards | Quantitative elemental imaging | Matrix-matched standards essential for accurate quantification |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Engineering metal-binding sites | Critical for testing hypotheses about metal-ligand interactions |

| Anaerobic Chambers | Handling oxygen-sensitive metalloproteins | Essential for studying Fe-S proteins and other oxygen-sensitive metal sites |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | Access to XFM, EXAFS, and micro-crystallography | Competitive application process; requires advanced sample preparation |

Biomedical Implications and Future Directions

Metalloproteins in Human Health and Disease

Dysregulation of metal homeostasis and metalloprotein function is implicated in numerous human diseases [5] [6]. Neurological disorders including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases are characterized by disturbed homeostasis of redox-active metals [5]. In Alzheimer's disease, metallic copper and iron in elemental states (Cu⁰ and Fe⁰) have been discovered within amyloid plaque cores, suggesting novel mechanisms of metal-mediated toxicity [9].

Wilson's disease results from copper accumulation in liver and brain due to mutations in a copper-transporting ATPase [9]. Diagnostic approaches using LA-ICP-MS and XFM can detect hepatic copper overload, enabling earlier intervention [9]. Similarly, Menkes disease, caused by defective copper transport, leads to systemic copper deficiency with severe neurological consequences [9].

Cancer cells often exhibit altered metal metabolism, and metalloproteins are being explored as both diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets [6]. The zinc proteome of SARS-CoV-2 has been characterized, suggesting potential roles for zinc in viral replication and host response [6].

Therapeutic Applications and Metallodrug Development

Metal-based drugs represent a growing area of pharmaceutical development [6]. Platinum compounds (cisplatin, carboplatin) are widely used cancer chemotherapeutics, while other metal complexes are being investigated for antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory applications [6]. Understanding the interactions between these metallodrugs and their biological targets requires sophisticated bioinorganic approaches [6].

The design of artificial metalloproteins with therapeutic functions is an emerging frontier [8]. By incorporating metal centers with desired reactivities into protein scaffolds, researchers aim to create targeted therapies with enhanced specificity and reduced side effects compared to traditional small-molecule drugs [8].

Future Challenges and Opportunities

Despite significant advances, numerous challenges remain in the field of metalloprotein research [10]. Predicting dynamic metal-binding sites, determining functional metalation states, and designing intricate coordination networks represent ongoing challenges in predictive modeling of metal-binding sites [10]. Addressing these challenges will require stronger interdisciplinary collaboration between bioinorganic chemists, biophysicists, and biologists [5].

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated methods for studying metalloproteins in native cellular environments, elucidating metal trafficking and delivery pathways, and engineering artificial metalloenzymes with novel catalytic activities [8] [9]. These advances will not only deepen our understanding of natural metalloproteins but also accelerate the development of metalloprotein-based technologies for medicine, energy, and industry [8].

Essential metal ions are indispensable components of biological systems, serving structural and catalytic roles that enable the remarkable chemical transformations underlying life processes. Through precise coordination environments within protein scaffolds, metal ions confer stability, enable electron transfer, and catalyze challenging chemical reactions with exquisite specificity and efficiency. Advances in analytical techniques, particularly quantitative elemental imaging methods, are revealing new dimensions of metal function in health and disease. The ongoing design and engineering of artificial metalloproteins represents both a test of our fundamental understanding and a pathway to novel biocatalysts and therapeutics. As research in this field continues to advance, it promises to yield deeper insights into biological function and innovative approaches to addressing human disease.

Metalloenzymes, which utilize metal ions or metal cofactors to catalyze chemical reactions, represent a cornerstone of bioinorganic chemistry. These enzymes facilitate some of the most challenging transformations in biology, including methane oxidation, dinitrogen fixation, and dioxygen activation [11] [12]. The metal centers within these enzymes enable this broad reactivity through sophisticated mechanisms involving electron transfer, oxygen binding, and substrate activation, often under mild physiological conditions using Earth-abundant metals [12]. Understanding these mechanisms provides fundamental insights into biological processes and inspires the development of innovative biotechnologies and therapeutic strategies.

This technical guide examines the core mechanistic principles of metalloenzyme catalysis, focusing on three fundamental processes: electron transfer, oxygen binding/activation, and substrate transformation. We integrate recent research advances with experimental methodologies to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for understanding and investigating these complex biological catalysts. The insights gathered here frame metalloenzymes as sophisticated molecular machines whose study enriches our fundamental knowledge of bioinorganic chemistry while offering practical applications across chemical synthesis, biotechnology, and medicine.

Fundamental Mechanistic Principles

Electron Transfer Processes

Electron-transferring metalloenzymes play pivotal roles in biological energy conversion and catalysis. These enzymes facilitate the movement of electrons between biological molecules, enabling crucial processes such as dinitrogen reduction to ammonia and proton reduction to molecular hydrogen [12]. The metal clusters within these enzymes, such as the iron-molybdenum cofactor in nitrogenase or the unique copper clusters in oxidases, provide pathways for electron flow through reversible oxidation-state changes of the metal centers.

The mechanistic sophistication of these systems lies in their ability to manage electron flow while preventing destructive side reactions. For instance, in hydrogenases and nitrogenases, electronic interactions between metal atoms allow the metallocenters to bind substrates and shuttle electrons into and out of the active site [13]. This electron delocalization across metal clusters enables the accumulation of multiple reducing equivalents necessary for challenging multi-electron transformations like N₂ fixation. The protein scaffold surrounding these metal clusters plays a crucial role in tuning reduction potentials and providing gating mechanisms that control electron transfer timing relative to substrate binding and product release.

Oxygen Binding and Activation

Molecular oxygen presents unique challenges for biological activation due to its triplet ground state and strong O-O bond, which make it kinetically inert at room temperature [14]. Metalloenzymes overcome these limitations through sophisticated activation mechanisms employing primarily iron and copper ions at their active sites. These metal centers utilize their paramagnetic properties to bind and activate dioxygen, generating reactive high-valent species capable of oxidizing various substrates.

Table 1: Major Classes of Oxygen-Activating Metalloenzymes

| Enzyme Class | Metal Center | Representative Enzymes | Key Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heme Oxygenases | Iron (heme) | Cytochromes P450 (CYPs), OleTJE | Substrate hydroxylation, oxidative decarboxylation |

| Non-Heme Iron Oxygenases | Iron (mononuclear or diiron) | Soluble methane monooxygenases, catechol dioxygenases | Methane hydroxylation, catechol ring cleavage |

| Copper Oxidases | Type 2/3 copper centers | Laccase, tyrosinase, catechol oxidase | Substrate oxidation, quinone formation |

| Copper Oxygenases | Single copper center | Polysaccharide monooxygenases (PMOs) | Hydroxylation of polysaccharides |

The activation mechanism varies significantly between different metalloenzyme families. Heme-containing oxygenases like cytochromes P450 employ a thiolate-ligated heme iron that activates molecular oxygen to form a highly reactive iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin π-cation radical species (Compound I) capable of hydrogen atom abstraction from unactivated C-H bonds [14]. Non-heme iron enzymes utilize a 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad motif that leaves three coordination sites available for oxygen and substrate binding, enabling alternative activation pathways [14]. Copper-containing oxygenases employ type 2, type 3, or trinuclear copper clusters, with the specific arrangement dictating their reactivity patterns [14].

Substrate Activation Mechanisms

Metalloenzymes activate substrates through diverse mechanisms that leverage the unique properties of metal centers. The metal can display distinct roles, including serving as a Lewis acid to polarize substrate bonds, generating reactive oxygen species, or directly participating in redox chemistry [15]. The coordination environment of the metal center precisely orients the substrate for transformation and stabilizes transition states through second-sphere interactions.

Two primary mechanisms for substrate activation have been identified: inner-sphere and outer-sphere activation. In inner-sphere mechanisms, the substrate directly coordinates to the metal center, leading to bond polarization upon coordination [15]. This direct coordination is observed in enzymes like carbonic anhydrase, where CO₂ coordinates to a zinc-bound hydroxide, enhancing its nucleophilicity. In outer-sphere mechanisms, the metal acts as an electrostatic activator in its hydrated form without direct substrate coordination [15]. Metal lability plays a crucial role in determining which mechanism operates, with more labile metals favoring outer-sphere pathways.

For C-H activation reactions, many metalloenzymes employ quantum mechanical tunneling, where the hydrogen nucleus moves through rather than over the energy barrier [16]. The protein scaffold plays a critical role in these reactions by creating short tunneling distances and degenerate energy levels as prerequisites for productive wave function overlap between reactant and product states [16].

Diagram 1: Core mechanistic pathways in metalloenzyme catalysis showing the three fundamental processes and their key sub-mechanisms.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Spectroscopic Techniques for Mechanistic Studies

Advanced spectroscopic methods provide crucial insights into metalloenzyme structure and mechanism. These techniques probe the coordination environments, electronic structures, and dynamic properties of metal centers during catalysis.

Table 2: Key Spectroscopic Methods for Metalloenzyme Characterization

| Technique | Information Obtained | Applications in Metalloenzyme Research |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Oxidation state, coordination symmetry, metal environment | Identification of paramagnetic T2-Cu sites in copper oxidases [13] |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) | Metal oxidation state, coordination number, bond distances | Determination of Cu-Cu distances in copper clusters (~2.59 Å, ~3.75 Å) [13] |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) | Protein flexibility, dynamics, allosteric networks | Detection of thermal activation pathways through TDHDX [16] |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Secondary structure, chiral organization | Characterization of G-quartet formation in nucleotide-containing assemblies [13] |

X-band continuous-wave EPR spectroscopy provides detailed information about the ground-state electronic states of paramagnetic metal centers through g-values (g// and g┴) and hyperfine coupling constants (A values) that reflect coordination environments and unpaired electron density in specific orbitals [13]. For copper enzymes, EPR parameters (g// of 2.22-2.30, A// of 158-200 × 10⁻⁴ cm⁻¹) help identify type 2 copper sites in native enzymes and artificial mimics [13]. XAS at metal K-edges reveals oxidation states through pre-edge transition intensities and provides metrical parameters like metal-metal distances through EXAFS analysis, with Cu-Cu distances of ~2.59 Å and ~3.75-3.84 Å observed in self-assembled copper clusters mimicking native enzymes [13].

Temperature-dependent HDX (TDHDX) has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying catalytically relevant site-specific protein thermal networks [16]. By comparing mutant enzyme forms with altered activation energies, TDHDX reveals the impact of mutation on Ea for local protein unfolding, uncovering thermal networks that track to the dictates of the catalyzed reaction rather than protein scaffold conservation [16].

Protein Design and Engineering Approaches

The design and engineering of artificial metalloenzymes employs three primary strategies: de novo design, miniaturization, and protein redesign [14]. These approaches leverage advances in computational, molecular, and structural biology to create metal-containing biocatalysts with functions comparable to or even beyond those found in nature.

De novo design constructs entirely new protein scaffolds tailored to accommodate specific metal cofactors and catalytic functions. This approach has produced functional sites like the Hg(II)-stabilized Zn(II) center in artificial carbonic anhydrases, which catalyzes CO₂ hydration with efficiency comparable to natural enzymes [14]. Miniaturization simplifies complex metalloenzymes to their essential functional elements, creating structurally minimalistic yet catalytically competent mimics. Protein redesign introduces novel metal-binding sites into existing protein scaffolds, as demonstrated by the engineering of a nonheme iron binding site into myoglobin to create a functional nitric oxide reductase mimic [14].

Computational design combined with directed evolution represents a particularly powerful strategy. The RosettaMatch and RosettaDesign methodologies can identify mutations that create new metal-binding sites, with subsequent directed evolution optimizing catalytic efficiency [14]. This approach has generated redesigned enzymes with catalytic efficiencies (kcat/KM) of ~10⁴ M⁻¹ s⁻¹ for non-native reactions [14].

Diagram 2: Integrated approaches for artificial metalloenzyme development showing the convergence of computational, synthetic, and evolutionary strategies.

Supramolecular Assembly Strategies

Supramolecular chemistry offers innovative approaches for constructing metalloenzyme mimics through self-assembling building blocks. These systems create enzyme-like active sites through noncovalent interactions that position functional groups in precise spatial arrangements comparable to native enzymes [13]. This approach has generated catalysts like the self-assembled system comprising guanosine monophosphate (GMP), Fmoc-lysine, and Cu²⁺ that forms oxidase-mimetic copper clusters with performance surpassing previously reported artificial complexes [13].

The structural flexibility of supramolecular assemblies mimics the dynamic behavior of native enzymes, facilitating substrate access to active sites. In the GMP/Fmoc-K/Cu²⁺ system, fluorenyl stacking enables periodic arrangement of amino acid components to form coordinatively unsaturated copper centers resembling native enzyme active sites, while nucleotides provide additional coordination atoms that enhance copper activity through facilitated copper-peroxide intermediate formation [13]. These supramolecular catalysts exhibit remarkable robustness, maintaining activity up to 95°C in aqueous environments [13].

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metalloenzyme Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Derivatives | Fmoc-lysine, Fmoc-modified amino acids | Construction of supramolecular enzyme mimics through self-assembly [13] |

| Nucleotide Components | Guanosine monophosphate (GMP), other nucleotides | Provide coordination atoms (nucleobase, phosphate) in hybrid catalysts [13] |

| Metal Salts | CuSO₄, Cu²⁺ salts, Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ salts, Zn²⁺ salts | Metal cofactor source for native and artificial metalloenzymes [14] [13] |

| Spectroscopic Probes | D₂O for HDX, spin traps for EPR | Mechanistic studies of protein dynamics and metal center electronic structure [16] [13] |

| Protein Scaffolds | Native enzymes (myoglobin), de novo designed peptides | Engineering platforms for novel metal binding sites [14] |

| Computational Tools | RosettaMatch, RosettaDesign algorithms | Metal binding site prediction and protein scaffold design [14] |

The development and characterization of metalloenzymes require specialized reagents and materials that enable the construction, analysis, and optimization of these complex systems. Fmoc-modified amino acids serve as building blocks for supramolecular assemblies that create enzyme-like active sites through directional fluorenyl stacking interactions [13]. Nucleotides like GMP contribute both structural organization through G-quartet formation and metal coordination functionality in hybrid catalyst systems [13].

Metal salts provide essential cofactors for native and artificial metalloenzymes, with copper salts particularly important for constructing oxidase and oxygenase mimics [14] [13]. Spectroscopic probes like D₂O enable hydrogen-deuterium exchange studies that reveal protein dynamics and allosteric networks, while spin traps facilitate EPR investigations of paramagnetic metal centers [16] [13]. Both native protein scaffolds (e.g., myoglobin) and de novo designed peptides provide structural frameworks for engineering novel metal binding sites with tailored catalytic functions [14].

The mechanistic investigation of metalloenzyme catalysis reveals sophisticated biological solutions to challenging chemical transformations. Through intricate coordination chemistry and precisely tuned protein environments, these enzymes achieve remarkable catalytic efficiency and selectivity using Earth-abundant metals. The integrated application of spectroscopic, computational, and protein engineering approaches continues to unravel the complex interplay between metal centers and their protein scaffolds that enables these functions.

The insights gained from studying natural metalloenzymes directly inform the design of artificial catalysts with tailored properties for synthetic and therapeutic applications. As research methodologies advance, particularly in areas of protein dynamics analysis and supramolecular assembly, our ability to understand and mimic these natural catalysts continues to grow. This progress strengthens the foundation of bioinorganic chemistry while providing innovative solutions to challenges in energy conversion, chemical synthesis, and pharmaceutical development.

Metal ions are fundamental components in biological systems, serving as crucial cofactors for approximately one-third of all proteins and participating in a vast array of physiological processes including enzyme catalysis, electron transfer, oxygen transport, and signal transduction [5] [17]. The field of bioinorganic chemistry investigates the complex interactions between inorganic metal ions and biological molecules, seeking to understand how organisms maintain metal ion homeostasis—the precise balance of metal uptake, storage, trafficking, and efflux required for optimal biological function [18]. Disruption of this delicate equilibrium is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in numerous human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, making the study of metal homeostasis critically important for therapeutic development [19] [20].

The postgenomic era has revolutionized bioinorganic chemistry, presenting unprecedented opportunities to explore the connections between genomic information and inorganic elements [18]. Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in understanding how metal trafficking pathways are integrated into cellular networks and how metal homeostasis influences broader biological systems. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of current knowledge regarding metal homeostasis mechanisms, experimental approaches for their study, and implications for therapeutic interventions against human disease.

Essential Metal Ions and Their Biological Roles

Classification and Functions of Biological Metals

Metal ions in biological systems can be broadly categorized as either essential or non-essential. Essential metals include both main group elements (sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca)) and transition metals (manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and molybdenum (Mo)) [5]. These elements play indispensable roles in maintaining physiological processes:

- Iron (Fe): Exists primarily as Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ and serves as a cofactor for hemoglobin, cytochromes, and numerous enzymes involved in electron transfer and oxygen transport [21].

- Copper (Cu): Functions as an essential catalytic cofactor in redox-active enzymes including cytochrome c oxidase, superoxide dismutase, and tyrosinase [18].

- Zinc (Zn): Predominantly found as Zn²⁺ and plays structural roles in transcription factors (zinc fingers) and catalytic roles in hydrolases [5].

- Manganese (Mn): Acts as a cofactor for enzymes such as Mn-superoxide dismutase and plays a role in development, metabolism, and antioxidant defense [22].

Table 1: Essential Transition Metals and Their Biological Functions

| Metal Ion | Common Oxidation States | Key Biological Functions | Associated Proteins/Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) | Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺ | Oxygen transport, electron transfer, DNA synthesis | Hemoglobin, cytochromes, ferritin, ribonucleotide reductase |

| Copper (Cu) | Cu⁺, Cu²⁺ | Electron transfer, oxidative stress protection, pigment formation | Cytochrome c oxidase, Cu/Zn-SOD, tyrosinase, ceruloplasmin |

| Zinc (Zn) | Zn²⁺ | Structural coordination, catalytic activity, gene regulation | Zinc finger proteins, carbonic anhydrase, alcohol dehydrogenase |

| Manganese (Mn) | Mn²⁺, Mn³⁺ | Antioxidant defense, bone development, metabolism | Mn-SOD, arginase, glycosyltransferases |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | Mo⁴⁺, Mo⁵⁺, Mo⁶⁺ | Oxotransferase reactions, purine catabolism | Xanthine oxidase, sulfite oxidase, aldehyde oxidase |

Challenges in Metal Homeostasis

The same chemical properties that make metal ions biologically essential—including their redox activity, binding affinity, and coordination geometry—also present significant challenges for biological systems [23]. Transition metals such as iron and copper can participate in Fenton chemistry, generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that damage cellular components including DNA, proteins, and membranes [5]. The poor solubility of many metal ions under physiological conditions further complicates their bioavailability and transport [23] [24]. Additionally, the similar chemical properties among different metals can lead to competition and mis-metalation of protein binding sites, potentially disrupting normal cellular functions [23].

Cellular and Systemic Metal Homeostasis Mechanisms

Principles of Metal Homeostasis

Biological systems maintain metal homeostasis through sophisticated regulatory networks that coordinate metal acquisition, distribution, storage, and elimination [18]. These processes ensure that essential metals are delivered to their correct destinations in appropriate quantities while minimizing toxic side effects. At the cellular level, homeostasis is achieved through the integrated function of membrane transporters, metal chaperones, storage proteins, and sensing mechanisms that respond to fluctuating metal levels [17] [18].

In complex multicellular organisms, metal homeostasis operates at both systemic and cellular levels, requiring specialized barriers and carriers to control metal movement between compartments [23]. The plasma membrane represents the primary barrier to metal ion movement, with its phospholipid bilayer being largely impermeable to charged species [23]. Transmembrane transport proteins selectively facilitate the passage of specific metal ions, while intracellular organelles—particularly the vacuole in plants and analogous compartments in other organisms—serve as storage reservoirs that buffer metal concentrations [23].

Metal Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking

Cells possess specific uptake mechanisms for essential metals, often involving reduction steps to facilitate transport. For example, copper uptake in yeast involves reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) at the cell surface before transport across the membrane by Ctr proteins [18]. Once inside the cell, metal chaperones—specialized proteins that shuttle metals to specific targets—deliver ions to their cognate enzymes and storage proteins while minimizing exposure to the cytosolic environment [18].

The copper chaperone Atx1 delivers copper to the Ccc2 transporter for incorporation into Fet3, while CCS specifically loads copper onto superoxide dismutase, and Cox17 shuttles copper to mitochondria for assembly of cytochrome c oxidase [18]. These protein-mediated trafficking pathways ensure metal delivery to appropriate targets while preventing inappropriate interactions that could generate reactive oxygen species or cause mis-metalation of other proteins.

Storage and Detoxification Mechanisms

When metal concentrations exceed immediate cellular requirements, excess ions are sequestered by storage proteins or compartmentalized within organelles. Ferritin serves as the primary storage protein for iron, accommodating up to 4,500 iron atoms in a non-toxic, bioavailable form [21]. Similar storage mechanisms exist for other metals, including metallothioneins for copper and zinc [20].

Intracellular organelles, particularly the vacuole in plants and fungi and analogous compartments in mammalian cells, play crucial roles in metal detoxification and homeostasis. Vacuolar transporters such as HMA3 (a heavy metal ATPase) sequester excess metals away from the cytosol, with loss-of-function mutations leading to increased metal sensitivity and altered distribution [23].

Metal Homeostasis in Plants: A Model System

Barriers to Metal Transport

Plants face unique challenges in metal homeostasis due to their sessile nature and need to acquire minerals from the soil. The rhizosphere and cell wall represent initial barriers that immobilize metals through binding to negatively charged polymers such as pectin and hemicellulose [23]. Soil pH significantly influences metal bioavailability, with alkaline conditions reducing the solubility of iron and zinc while increasing availability of molybdenum [23].

The Casparian strip and suberin deposits in cell walls create apoplastic barriers that restrict the free diffusion of metal ions, requiring specialized transport systems for metal movement throughout the plant [23]. The plasma membrane presents a significant barrier to metal movement, with its phospholipid bilayer being impermeable to charged ions, necessitating specific transport proteins for metal uptake and distribution [23].

Carrier Systems in Plants

To overcome these barriers, plants have evolved sophisticated carrier systems involving membrane transporters, low-molecular-weight ligands, and vesicle trafficking mechanisms [23] [24]. Metal chelators such as nicotianamine and phytosiderophores facilitate metal solubilization and transport, while ATP-driven transporters of the HMA family mediate metal transport across cellular membranes [23].

The iron-regulated transporter IRT1 plays a particularly important role in iron uptake but also transports other metals including cadmium, highlighting the potential for toxic metal accumulation when homeostasis is disrupted [23]. This interplay between essential and toxic metals underscores the importance of precise regulatory mechanisms in maintaining appropriate metal balance.

Metal Homeostasis in Mammalian Systems and Disease Connections

Metal Dyshomeostasis in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Increasing evidence connects disruption of metal homeostasis with the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [19] [20]. The brain has a high demand for essential metals but is particularly vulnerable to metal imbalance due to its high oxygen consumption and lipid content.

Table 2: Metal Dyshomeostasis in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Affected Brain Regions | Metal Alterations | Associated Pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Hippocampus, cerebral cortex | Iron accumulation in plaques and tangles; copper and zinc dysregulation | Amyloid-β plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, oxidative stress |

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Substantia nigra, globus pallidus | Iron deposition in substantia nigra; decreased ferritin | Lewy bodies (α-synuclein aggregation), dopaminergic neuron loss |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | Motor cortex, spinal cord | Copper dysregulation; manganese involvement | SOD1 aggregation, motor neuron degeneration |

| Huntington's Disease (HD) | Basal ganglia, cortex | Altered copper and iron metabolism | Huntingtin protein aggregates, striatal neuron loss |

Iron deposition was first observed in the brains of PD patients as early as 1924 and in AD patients in 1953 [19]. Subsequent research has confirmed that brain iron content increases with age and is further elevated in neurodegenerative conditions, where it may promote protein aggregation and oxidative damage [19]. The interaction between excess iron and proteins such as α-synuclein in PD or amyloid-β and tau in AD creates a vicious cycle of oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and neuronal dysfunction [19].

Metal Ions in Cancer and Therapeutic Opportunities

The essential role of metals in cell proliferation makes metal homeostasis a critical factor in cancer biology [21]. Tumor cells frequently exhibit reprogrammed metal metabolism to support their rapid growth, often resulting in elevated intracellular iron, copper, and zinc levels compared to normal cells [21]. This altered metal metabolism creates therapeutic opportunities:

- Ferroptosis Induction: An iron-dependent form of programmed cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation, which can be triggered in cancer cells by disrupting iron homeostasis [21].

- Fenton Reaction-Mediated Toxicity: Exploiting the high iron and hydrogen peroxide levels in tumor cells to generate cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals [21].

- Copper Disruption: Altering copper availability to inhibit angiogenic processes that depend on copper-containing enzymes [20].

Metal-based nanomaterials are being developed to target these vulnerabilities, with various iron oxide nanoparticles and copper chelators showing promise in preclinical models [21].

Experimental Approaches in Metal Homeostasis Research

Metalloproteomics Methodologies

The emerging field of metalloproteomics aims to characterize metal-protein interactions on a proteome-wide scale, providing insights into metal distribution, speciation, and function in biological systems [25]. Key methodologies include:

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): Enables sensitive detection and quantification of metal elements in biological samples, with single-cell resolution approaches (scICP-MS) allowing analysis of cell-to-cell heterogeneity [25].

- Mass Cytometry (CyTOF): Combines elemental tagging with flow cytometry to simultaneously measure multiple parameters in individual cells, enabling high-dimensional analysis of metal-related cellular processes [25].

- Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Provides spatially resolved information about element distribution in tissues and cells with subcellular resolution [25].

These techniques are complemented by molecular biology approaches, including genetic screening in model organisms like yeast, which has identified numerous genes involved in metal homeostasis through systematic growth assays under varying metal conditions [17].

Visualization of Metal Homeostasis Networks

The complexity of metal homeostasis networks necessitates visual representations to comprehend the interconnected pathways. The following diagram illustrates the key components and their relationships in cellular copper homeostasis:

Diagram 1: Cellular Copper Homeostasis Network. This diagram illustrates the primary pathways for copper uptake, trafficking, and utilization in eukaryotic cells, highlighting the roles of specific chaperones in delivering copper to target proteins.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metal Homeostasis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Chelators | Clioquinol, Deferiprone, Deferoxamine, Curcumin | Clinical trials for neurodegenerative diseases; in vitro metal chelation | Selective capture of specific metal ions; dissociation from pathological sites |

| Metal Sensors | DNAzyme-based fluorescent sensors, FRET-based metal indicators | Live-cell imaging of metal dynamics; monitoring redox states | Selective detection of specific metal ions and oxidation states in biological systems |

| Nanoparticles | Fe3O4-NPs, Polydopamine nanoparticles, Cerium oxide nanoparticles | Tumor therapy studies; drug delivery systems; induction of ferroptosis | Fenton reaction catalysis; ROS generation; drug carrier functionality |

| Isotopic Tracers | Stable isotopes of Fe, Cu, Zn for ICP-MS | Metabolic tracing studies; quantification of metal flux | Tracking metal absorption, distribution, and turnover in biological systems |

| Genetic Tools | Yeast knockout collections, CRISPR-Cas9 libraries | Functional genomics screens; identification of metal-related genes | Systematic identification of genes involved in metal homeostasis pathways |

Therapeutic Targeting of Metal Homeostasis

Chelation-Based Strategies

Metal chelators represent the most direct approach to correcting metal dyshomeostasis in human disease [19] [20]. These compounds selectively bind specific metal ions, potentially reversing pathological metal accumulation or redistribution:

- Deferiprone: An iron chelator that has shown neuroprotective effects in early-stage Parkinson's disease patients by chelating labile iron [19].

- Clioquinol: A copper and zinc chelator that has demonstrated potential in Alzheimer's disease models by redistributing metals and reducing amyloid pathology [19].

- Curcumin: A natural product with metal-chelating properties that can bind copper, iron, and zinc, potentially contributing to its neuroprotective effects [19].

The therapeutic efficacy of chelation approaches depends on multiple factors including metal specificity, blood-brain barrier penetration, and the ability to address metal deficiency in some compartments while correcting excess in others [20].

Nanomaterial Applications

Metal-based nanomaterials offer innovative approaches to modulating metal homeostasis for therapeutic benefit, particularly in oncology [21]:

- Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs): Can induce ferroptosis in tumor cells through Fenton reaction-mediated ROS generation and disruption of cellular iron balance [21].

- Ferritin-Targeting Nanoparticles: Designed to hijack endogenous iron stores, releasing Fe²⁺ specifically within tumor cells to trigger selective cell death [21].

- Combination Nanosystems: Incorporate both metal ions and chemotherapeutic agents for synergistic effects, such as iron nanoparticles combined with cisplatin [21].

These approaches leverage the unique physicochemical properties of nanomaterials to achieve spatial and temporal control over metal ion delivery and activity, potentially overcoming limitations of conventional small-molecule therapies.

Future Perspectives in Metal Homeostasis Research

The study of metal homeostasis in biological systems continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Systems-level approaches that integrate metallomic, proteomic, and genetic data will be essential for understanding how metal homeostasis networks function as integrated systems rather than as isolated pathways [17]. The development of advanced analytical methods with improved sensitivity, spatial resolution, and capacity for multi-element analysis will enable more comprehensive characterization of metal distributions and speciation in health and disease [25].

From a therapeutic perspective, cell-type specific targeting represents an important frontier, as different cell types within tissues (such as neurons versus glia in the brain) may exhibit distinct metal homeostasis mechanisms and vulnerabilities [22]. The emerging understanding of metal-mediated cell death pathways such as ferroptosis and cuproptosis provides new conceptual frameworks for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted interventions [19] [21].

As research in these areas advances, it will continue to highlight the fundamental importance of metal homeostasis in human health and disease, offering new opportunities for therapeutic innovation in conditions ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to cancer.

Bioinorganic chemistry investigates the crucial roles of metal ions and metallocofactors within biological systems. Among the most widespread and versatile of these cofactors are iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, which are essential for fundamental processes including electron transfer, catalytic activity, and gene regulation across all domains of life [26]. These clusters exist in several structural forms, from simple [2Fe-2S] rhombic structures to cubane [4Fe-4S] clusters, and even more complex arrangements such as the [8Fe-7S] cluster found in nitrogen-fixing bacteria [26]. The evolutionary significance of Fe-S clusters is profound; mitochondrial Fe-S cluster biosynthesis pathways are highly conserved from bacteria, reflecting the bacterial origins of mitochondria through endosymbiosis [26]. The assembly of these clusters was potentially a fundamental contribution of the initial endosymbiont and remains essential for eukaryotic cell survival [26].

This whitepaper focuses on three critical manifestations of these metallocofactors: the ubiquitous iron-sulfur clusters, the heterometallic nickel-iron-sulfur active site of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH), and the light-driven electron transfer chains of photosynthetic reaction centers. These systems exemplify how nature ingeniously employs inorganic metal clusters to drive complex biochemical transformations. Understanding their precise structure, assembly mechanisms, and catalytic functions provides invaluable insights for researchers and drug development professionals, offering blueprints for bio-inspired catalysts, therapeutic agents targeting metalloenzymes, and tools for synthetic biology. The following sections provide an in-depth technical analysis of these systems, complete with quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualizations of their core mechanisms.

Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Ubiquitous Biological Cofactors

Structure, Function, and Assembly

Iron-sulfur clusters are among nature's most modular and multipurpose structures, serving as essential cofactors for a diverse array of iron-sulfur proteins [26] [27]. Their functions extend far beyond electron transfer to include roles in enzyme catalysis, regulation of gene expression in response to oxidative stress and oxygen levels, and DNA replication and repair [26]. Table 1 summarizes the common types of iron-sulfur clusters, their typical structures, and primary biological functions.

Table 1: Common Types of Iron-Sulfur Clusters and Their Functions

| Cluster Type | Structural Description | Primary Biological Functions | Example Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2Fe-2S] | Rhombic structure; two iron atoms bridged by two sulfide atoms [26]. | Electron transfer; catalytic cofactor [26]. | Plant ferredoxins; mitochondrial Complex I & III (Rieske protein) [26] [27]. |

| [4Fe-4S] | Cubic structure with iron and sulfur at alternating corners [26]. | Electron transfer; catalytic cofactor; structural regulation [26]. | Bacterial ferredoxins; mitochondrial Complex I; DNA repair enzymes [26]. |

| [3Fe-4S] | Less common cubane-type cluster [26]. | Electron transfer; catalytic cofactor. | Quinone-binding site of mitochondrial Complex II [26]. |

| NEET [2Fe-2S] | [2Fe-2S] cluster coordinated by three cysteine and one histidine residue [27]. | Regulatory roles, potentially in iron and reactive oxygen species metabolism. | Mammalian cells. |

| Rieske [2Fe-2S] | [2Fe-2S] cluster coordinated by two cysteine and two histidine residues [27]. | Electron transfer in high-potential conditions. | Cytochrome b₆f complex; mitochondrial Complex III [26] [27]. |

The biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters is a highly regulated process, not spontaneous. Intracellular assembly is catalyzed and modulated by conserved protein machineries in discrete subcellular compartments like mitochondria and chloroplasts [27]. In plant mitochondria, the Iron-Sulfur Cluster (ISC) assembly machinery is a key system. As shown in Figure 1, the process involves multiple steps: First, the Nfs1-Isd11 complex desulfurates cysteine, providing inorganic sulfide, while frataxin likely serves as an iron donor and regulator. The iron and sulfur are then assembled into a transient cluster on the Isu1 scaffold protein. Subsequently, the Hsp70 chaperone system (HscA/HscB) facilitates the transfer of the cluster from Isu1 to recipient apo-proteins, a process that may require additional carrier proteins like IscA and NFU proteins [27]. The final step involves the insertion of the mature cluster into a diverse set of iron-sulfur proteins, including components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Complexes I, II, and III) and metabolic enzymes like fumarase [27].

Figure 1: Proposed mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Cluster (ISC) assembly pathway in plants, based on models from yeast and Arabidopsis thaliana [27].

Experimental Analysis of Iron-Sulfur Clusters

Studying the structure and function of Fe-S clusters requires a suite of specialized biochemical and biophysical techniques. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for the heterologous expression, purification, and initial characterization of Fe-S proteins.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dithionite | A strong reductant used to maintain clusters in their reduced state. | Investigating the reduced, catalytically active form of CODH [28]. |

| Cysteine | Source of inorganic sulfur during Fe-S cluster biogenesis. | In vitro reconstitution of Fe-S clusters on scaffold proteins [27]. |

| Frataxin | Iron donor and/or regulator in the ISC assembly machinery. | Studying the initial stages of Fe-S cluster synthesis in mitochondria [27]. |

| IscU/Isu1 Scaffold Protein | Platform for de novo Fe-S cluster assembly. | In vitro studies of cluster formation kinetics and mechanism [27]. |

| Rotenone | Classical inhibitor of Complex I; binds to Fe-S clusters. | Probing the role of Fe-S clusters in mitochondrial electron transport [26]. |

Protocol 1: Heterologous Expression and Purification of an Fe-S Protein

- Gene Cloning and Expression: Clone the gene of interest into an appropriate expression vector. Transform into a suitable host (e.g., E. coli or, for complex metalloenzymes, specialized hosts like Desulfovibrio fructosovorans [28]). Induce protein expression, often in media supplemented with iron to facilitate cluster incorporation.

- Anaerobic Purification: Perform all purification steps under anaerobic conditions (in a glovebox or using Schlenk techniques) to prevent oxidative degradation of oxygen-sensitive Fe-S clusters. Use affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification) followed by size-exclusion chromatography.

- Initial Characterization:

- Metal Analysis: Determine iron and sulfur content using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or colorimetric assays. This quantifies cluster loading.

- UV-Visible Spectroscopy: Obtain an absorption spectrum. Fe-S clusters typically exhibit broad absorbance in the 300-500 nm range.

- Activity Assay: Perform a tailored enzyme activity assay. For electron transfer proteins, this may involve monitoring reduction of a partner protein or artificial electron acceptor.

For deeper mechanistic insights, advanced spectroscopic techniques are indispensable:

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy: Used to study paramagnetic states of Fe-S clusters (e.g., reduced [4Fe-4S]⁺ clusters). Can detect and differentiate cluster types in a protein, as seen in studies of Photosystem I [29].

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): Probes the coordination environment and oxidation states of metal ions (Fe, Ni) within metalloenzymes, providing information without the need for crystals [30].

- X-ray Crystallography: The gold standard for determining atomic-resolution structures of metalloenzymes, revealing the precise geometry of clusters like the C-cluster in CODH [28].

Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenase (CODH): A Case Study in Complex Metallocluster Assembly

Classification and Structural Features

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenases (CODHs) are remarkable metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible oxidation of CO to CO₂. They are broadly classified into two structurally and mechanistically distinct types: the molybdenum-containing Mo-CODH found in aerobic bacteria, and the nickel-dependent Ni-CODH found in anaerobic bacteria and archaea [31]. Ni-CODHs exhibit catalytic activities nearly 1000 times higher than their Mo-containing counterparts [31].

The catalytic heart of anaerobic CODH is the C-cluster, a unique heterometallic nickel-iron-sulfur cluster with the composition Ni-3Fe-4S [28]. Its canonical structure consists of a distorted [Ni-3Fe-4S] cubane linked via a bridging sulfide ligand to a so-called "unique" iron site (Feᵤ) [28]. This cluster is housed within a homodimeric protein that also contains additional electron transfer clusters: the B-cluster ([4Fe-4S]) and the D-cluster (either [4Fe-4S] or [2Fe-2S]), which shuttle electrons to and from the active site [28] [31].

Maturation and Metallocluster Insertion

The assembly of the intact and functional C-cluster is a complex process requiring dedicated maturation machinery. A key player is CooC, a P-loop ATPase that is essential for nickel insertion into the C-cluster [28]. Recent structural studies have provided critical insights into this process, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Structural and Functional Analysis of CODH Maturation States

| CODH Sample | C-Cluster Nickel Content | C-Cluster Iron Content | CO Oxidation Activity (μmol·min⁻¹·mg⁻¹) | Key Structural Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DvCODH + CooC (As-isolated) | 0.4 – 0.9 / monomer | 8 – 10.5 / monomer | 160 | Contains a partially nickel-loaded, canonical C-cluster. | [28] |

| DvCODH + CooC (Ni²⁺/Dithionite reconstituted) | Increased | Unchanged | ~1660 | Cluster is fully assembled and activated. | [28] |

| DvCODH - CooC (As-isolated) | 0 – 0.2 / monomer | 7.5 – 8.5 / monomer | <5 | C-cluster is fully loaded with iron, but lacks nickel. Feᵤ mis-incorporated into the Ni site. | [28] |

| DvCODH (C301S) + CooC | 0 / monomer | ~13 / monomer | Not Detectable | Partially assembled C-cluster; Feᵤ occupies both its canonical site and the Ni site. | [28] |

| DvCODH (ΔD-cluster) + CooC | 0.02 / monomer | 8 ± 1 / monomer | <5 | C-cluster contains iron but no nickel, despite CooC presence. | [28] |

The data in Table 3 reveals critical aspects of C-cluster assembly:

- CooC is essential for nickel insertion: Without CooC, the C-cluster is iron-replete but nickel-deficient, and the enzyme is largely inactive [28].

- An empty nickel site is not sufficient: The D-cluster, though distant from the active site, is also required for nickel incorporation. Its role may involve redox communication or conformational coupling [28].

- The oxidized state may be a maturation intermediate: The cysteine residue Cys-301, which ligates the cluster in its oxidized state, is critical for proper maturation. Its mutation prevents nickel insertion and leads to a mis-metallated cluster [28].

These findings support a model where C-cluster assembly requires CooC, a functioning D-cluster, precise redox control, and proceeds through a two-step nickel-binding process [28]. Figure 2 illustrates this proposed assembly pathway.

Figure 2: Proposed model for the maturation of the CODH C-cluster, highlighting the essential roles of the CooC maturase and the D-cluster [28].

Catalytic Mechanism and Synthetic Analogues

The C-cluster enables rapid and reversible CO/CO₂ interconversion. The mechanism is proposed to involve CO binding at the nickel ion, activating it for nucleophilic attack by a water molecule that is coordinated at the adjacent Feᵤ site [28] [32]. A key challenge in the field is resolving the electronic structures of catalytic intermediates and understanding the role of the unique low-coordinate nickel site [32]. This has spurred efforts to develop synthetic iron-nickel-sulfur clusters as models to study the fundamental inorganic chemistry underpinning the enzyme's remarkable efficiency [32].

Iron-Sulfur Clusters in Photosynthetic Reaction Centers

Role in Photosystem I