Automated Transition State Search: Global Optimization Methods for Accelerated Reaction Discovery in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to automated transition state (TS) search using global optimization algorithms for researchers and drug development professionals.

Automated Transition State Search: Global Optimization Methods for Accelerated Reaction Discovery in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to automated transition state (TS) search using global optimization algorithms for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational theory of TS geometry and its critical role in determining reaction kinetics. Methodological sections detail current global optimization techniques, including stochastic, metaheuristic, and machine learning-enhanced approaches, with specific applications in enzymatic and ligand-binding reactions. We address common computational challenges, convergence issues, and strategies for optimizing search efficiency and accuracy. The article concludes with validation protocols, benchmark comparisons of popular software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, AutoTS), and performance metrics, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for applying these methods to accelerate biomolecular reaction modeling and drug design.

Understanding Transition States: The Why and How of Global Optimization in Reaction Pathways

Within the research for an Automated transition state search using global optimization thesis, the precise definition of the transition state (TS) is foundational. The TS is not a stable intermediate but a critical configuration on the potential energy surface (PES) that represents the point of maximum energy along the minimum energy pathway connecting reactants and products. Its correct identification is paramount for calculating reaction rates, understanding selectivity, and guiding molecular design in fields like drug development. This document details the core concepts—geometry, energy, and the saddle point—and provides practical protocols for their characterization in computational studies.

Core Theoretical Concepts

2.1 The Saddle Point: A Mathematical Definition On a multi-dimensional PES, a first-order saddle point is characterized by:

- Gradient: The first derivative of the energy (∇E) is zero (a stationary point).

- Curvature: The second derivative (Hessian matrix) has exactly one negative eigenvalue. The corresponding eigenvector is the reaction coordinate. All other eigenvalues are positive.

2.2 Geometric and Energetic Signatures At the TS geometry:

- Bond Lengths/Angles: Typically, bonds in the process of being formed or broken have lengths intermediate between reactant and product values, often elongated.

- Energy: The TS resides at a local maximum along the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) but is a local minimum in all other orthogonal directions.

- Frequency: A single imaginary vibrational frequency (resulting from the negative force constant) is present. The vibrational mode corresponds to the motion along the reaction path towards reactants and products.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Stationary Points on a PES

| Characteristic | Reactant/Product (Minimum) | Transition State (First-Order Saddle Point) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Gradient (∇E) | Zero | Zero |

| Hessian Eigenvalues | All positive | One negative, rest positive |

| Vibrational Frequencies | All real | One imaginary (negative) |

| IRC Path | Endpoint | Apex |

| Geometry Stability | Stable, local minimum | Unstable, maximum along one coordinate |

Research Reagent Solutions (Computational Toolkit)

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for TS Analysis

| Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Package (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Performs electronic structure calculations to compute energy, gradients, and Hessians for molecular geometries. |

| IRC Follow Algorithm | Traces the minimum energy path from the TS downhill to confirm it connects to the correct reactant and product minima. |

| Hessian Matrix Calculator | Computes second derivatives of energy; essential for frequency analysis and confirming saddle point order. |

| Global Optimization Suite (e.g., TSSCDS, GENIUS, GMIN) | Automatically searches for multiple reaction pathways and TS structures without prior guess of the reaction coordinate. |

| Molecular Visualization Software (e.g., VMD, PyMOL, GaussView) | Visualizes geometries, vibrational modes (imaginary frequency), and reaction pathways. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Validating a Candidate Transition State Structure

Objective: To confirm that an optimized geometry is a first-order saddle point connecting the desired reactants and products.

Materials:

- Converged geometry output from a TS optimization calculation.

- Quantum chemistry software with frequency and IRC capabilities.

Methodology:

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency analysis on the candidate TS geometry at the same level of theory used for optimization.

- Analyze Output:

- Check for exactly one imaginary frequency (reported as a negative value in cm⁻¹).

- Visualize the vibrational mode associated with this imaginary frequency. The atomic motions should logically correspond to the bond-breaking/forming process of the intended reaction.

- IRC Calculation:

- Initiate an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate calculation from the TS geometry.

- Follow the path in both directions (mass-weighted steepest descent).

- Set sufficient steps and step size to reach minima.

- Geometry Verification:

- Optimize the geometries obtained at the termini of the IRC paths to convergence.

- Confirm that these optimized geometries match the expected reactant and product states.

Expected Outcome: A valid TS will have one imaginary frequency, and its IRC will connect to the reactant and product minima upon optimization.

Protocol 4.2: Automated TS Search via Dimer Method

Objective: To locate a transition state starting from an initial guess without manual input of the reaction coordinate, suitable for integration into global optimization workflows.

Materials:

- Initial reactant geometry.

- Computational code implementing the Dimer method (e.g., in ASE, LAMMPS, custom scripts).

Methodology:

- Initialization: Create an initial "dimer" comprising two images of the system separated by a small rotation.

- Rotation Step: Rotate the dimer to align its orientation with the lowest curvature mode (approximating the reaction coordinate direction).

- Translation Step: Move the dimer uphill along the approximated reaction coordinate and downhill in all perpendicular directions. This is typically done using forces modified to invert the component along the dimer direction.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until convergence criteria are met (e.g., force threshold, displacement between images).

- Validation: Upon convergence, apply Protocol 4.1 to validate the found saddle point.

Expected Outcome: An optimized TS geometry found through an automated, gradient-driven walk on the PES.

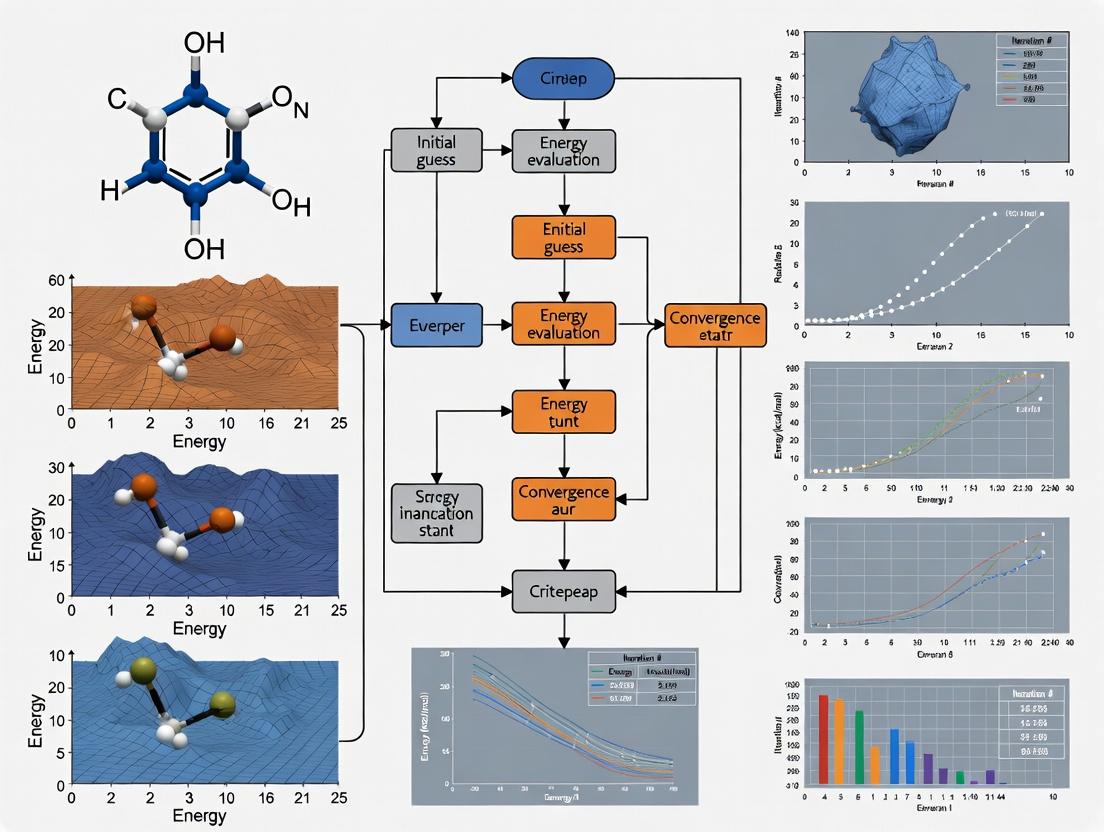

Visualization of Concepts & Workflows

Diagram 1: TS on the Reaction Pathway (Max Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: TS Validation Workflow (Max Width: 760px)

The Critical Role of TS Search in Predicting Reaction Rates and Mechanisms

Transition State (TS) search is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the prediction of reaction rates via Transition State Theory (TST) and elucidating detailed reaction mechanisms. Within the broader thesis of automated TS search using global optimization, the focus shifts from manual, intuition-driven searches to robust, algorithm-driven discovery of saddle points on potential energy surfaces (PES). This paradigm is critical for high-throughput screening in catalysis and drug development, where understanding reactivity and selectivity is paramount.

Core Principles and Quantitative Data

The rate constant k for an elementary reaction, according to conventional TST, is: k = Γ * (k_B T / h) * exp(-ΔG‡ / RT) where ΔG‡ is the Gibbs free energy of activation.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for TS Search and Their Performance Metrics

| Method Category | Specific Algorithm/Software | Key Performance Metric (Typical Range) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local TS Search | Berny Optimization (e.g., in Gaussian) | Success Rate: 70-85% (from good initial guess) | Refining known TS geometries. |

| Dimer Method | (e.g., in ASE, VASP) | Fewer force calls than NEB; Success ~60-75% | Reactions on solid surfaces. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) | Climbing Image NEB (CI-NEB) | Success Rate: 80-90% for clear pathways | Mapping minimum energy path (MEP). |

| Double-Ended Global Search | Growing String Method (GSM) | TS found within 50-100 iterations per image | Complex, barrierless reactions. |

| Automated Global PES Exploration | AFIR (Artificial Force Induced Reaction) | Can screen 1000s of pathways automatically | Unknown, multi-step mechanisms. |

| Machine Learning Assisted | ANI-2x, Neuroevolution | Reduces QM calculations by 50-90% | High-throughput virtual screening. |

Table 2: Impact of TS Accuracy on Predicted Rate Constants (Example: C-C Bond Formation)

| Level of Theory | Basis Set | Calculated ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | k (298 K) s⁻¹ | Error vs. Exp. (orders of mag.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM7 (Semi-empirical) | N/A | 18.5 | 1.2 x 10³ | +/- 2 |

| DFT (B3LYP) | 6-31G(d) | 25.1 | 1.5 x 10⁻¹ | +/- 1 |

| DFT (ωB97X-D) | def2-TZVP | 27.8 | 2.3 x 10⁻³ | ~0.5 |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | aug-cc-pVTZ | 28.5 | 7.1 x 10⁻⁴ | < 0.3 |

| Experimental Reference | - | 28.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 x 10⁻³ | - |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Automated TS Search for a Catalytic Cycle Using a Global Reaction Navigator

Objective: Systematically discover all elementary steps and TS structures in a transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction.

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit below.

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Optimize geometries of all suspected reactants, intermediates, and products at the DFT level (e.g., ωB97X-D/def2-SVP).

- Confirm all are true local minima via frequency analysis (no imaginary frequencies).

Conformational Sampling:

- Use a conformer search algorithm (e.g., CREST) on each minimum to generate low-energy conformers within a 5 kcal/mol window.

Global TS Search Execution:

- Employ an automated reaction explorer (e.g., the AFIR method as implemented in the GRRM program or AutoMeKin).

- Input all reactant and product minima from Step 1.

- Set parameters: Artificial force (γ) = 200 kJ/mol, maximum number of pathways = 200.

- Run the stochastic search. The algorithm will: a. Randomly perturb molecular geometries. b. Apply an artificial force to induce reactions. c. Follow the steepest descent path from located saddle points to connect minima. d. Output a list of located TSs and connected minima.

TS Validation:

- For each candidate TS, perform a frequency calculation. A valid TS must have exactly one imaginary frequency (typically 50i to 500i cm⁻¹).

- Visually inspect the vibrational mode corresponding to the imaginary frequency. It must smoothly connect the reactant and product along the reaction coordinate.

- Perform Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculations from the TS to confirm it connects to the correct reactant and product minima.

Energy Refinement:

- Re-optimize validated TS geometries and connected minima at a higher level of theory (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP//ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP).

- Calculate Gibbs free energies at the target temperature (e.g., 298 K).

Microkinetic Modeling:

- Use the computed free energy landscape (ΔG) to construct a microkinetic model.

- Calculate rate constants for each elementary step using TST.

- Solve the system of differential equations to predict overall rates, turnover frequencies (TOF), and the rate-determining step.

Automated TS Search Workflow for Catalytic Cycles

Protocol 3.2: High-Throughput TS Screening for Enzyme Inhibitor Design

Objective: Rank a library of drug-like molecules by the barrier height (ΔG‡) for a key covalent inhibition step.

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit.

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Obtain crystal structure of target enzyme with active site residue (e.g., a catalytic cysteine).

- Prepare the protein structure (add hydrogens, assign protonation states at physiological pH).

- Define a Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) region: the inhibitor scaffold and the reactive sidechain (QM), the rest of the protein (MM).

Initial State Modeling:

- Dock each candidate inhibitor into the active site.

- For each, perform MM geometry optimization followed by QM/MM optimization to obtain the reactant complex minimum.

Robust TS Search Protocol:

- Use the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method with 7-15 images to generate an initial path between the reactant complex and the product (covalent adduct).

- Employ the Climbing Image (CI) variant to precisely converge one image to the saddle point.

- Critical: Use an efficiently parallelizable QM method (e.g., DFTB, PM6, or ANI-2x potential) for the NEB/CI-NEB search.

TS Refinement & Scoring:

- Take the CI-NEB TS guess and perform a final, precise QM/MM TS optimization using a higher-level DFT functional.

- Calculate the final single-point energy at an even higher level (e.g., coupled-cluster) on the QM region.

- Compute ΔG‡ for each candidate. Rank the library; lower ΔG‡ suggests faster, more potent covalent inhibition.

High-Throughput TS Screening for Covalent Inhibitors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Automated TS Search

| Item (Software/Method) | Category | Primary Function in TS Search |

|---|---|---|

| GRRM (Global Reaction Route Mapping) | Global PES Explorer | Uses AFIR to automatically find TSs and reaction pathways without predefined guesses. |

| AutoMeKin | Global PES Explorer | Stochastic search of reaction networks; user-friendly for complex mechanisms. |

| CP2K (with NEB/CINEB) | DFT/NEB Code | Performs robust CI-NEB calculations, excellent for periodic systems (surfaces). |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python Toolkit | Provides flexible framework for scripting NEB, Dimer, and custom TS searches. |

| Gaussian 16 (IRC, Berny) | Quantum Chemistry | Industry standard for local TS optimization, IRC, and frequency analysis. |

| xtb/CREST (GFN-FF/GFN2-xTB) | Semi-empirical/ML | Ultra-fast conformational and PES sampling to generate initial guesses for TS. |

| ANI-2x Neural Network Potential | Machine Learning | Provides quantum-accurate energies/forces at MD speed, accelerating NEB searches. |

| Shermo | Thermodynamics | Calculates thermo properties (G, H, S) and TST rate constants from frequency outputs. |

| KineticME | Kinetic Modeling | Builds microkinetic models from computed energies to predict overall rates/selectivity. |

Limitations of Local Optimization and the Need for Global Search Strategies

The identification of transition states (TS) is a critical step in understanding reaction mechanisms in chemistry and biochemistry, particularly in computational drug discovery. Local optimization methods, such as the dimer method, nudged elastic band (NEB), and eigenvector-following, are fundamentally limited by their dependence on the initial starting geometry. They converge to the nearest stationary point on the potential energy surface (PES), which is often a local minimum or a first-order saddle point unrelated to the desired reaction pathway. Within the thesis on Automated transition state search using global optimization research, this document outlines the quantitative limitations of local methods and details protocols for implementing global search strategies to overcome these barriers.

Quantitative Limitations of Local Optimization Methods

The performance of local TS search algorithms is highly sensitive to the initial guess. The following table summarizes failure rates and computational costs from recent benchmark studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Local TS Search Methods (Benchmark Data)

| Method | Typical Success Rate (%) | Avg. CPU Hours per Successful TS (Small Molecule) | Critical Dependency | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimer Method | 40-60 | 8-15 | Initial dimer orientation & step size | Converges to nearest saddle, often incorrect. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) | 50-70 | 20-40 | Quality of initial path (images) | Paths can slide to minima, missing the true TS. |

| Eigenvector-Following (EF) | 30-50 | 5-12 | Initial Hessian matrix & step | Requires a good guess near the TS; fails otherwise. |

| Growing String Method | 60-75 | 25-50 | Endpoint geometries | Computationally intensive; local convergence remains. |

Data synthesized from recent computational studies (2023-2024) on organic molecule and enzyme model reaction databases.

Global Search Strategies: Protocols and Application Notes

Global search strategies aim to explore the PES broadly to locate low-energy reaction pathways without prior mechanistic bias.

Protocol 3.1: Automated TS Exploration via Stochastic Surface Walking (SSW)-Global Pathway Search

This protocol uses stochastic perturbations and local minimization to traverse high PES regions.

- Initialization: Generate 10-50 random initial structures from reactant and product conformers using molecular dynamics (MD) at high temperature (e.g., 2000K for 1 ps).

- SSW Cycle: a. Perturbation: Apply a random atomic displacement (0.5-1.0 Å max) combined with a bias toward lower energy (following the SSW algorithm). b. Local Relaxation: Use a fast local minimizer (e.g., L-BFGS) for 50-100 steps to quench the structure to a nearby minimum or saddle point. c. TS Identification: For each quenched structure, compute the Hessian matrix via a semi-empirical (PM6/PM7) or DFTB method. Structures with exactly one imaginary frequency (> -50 cm⁻¹) are flagged as candidate TS. d. Validation: Perform intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations from each candidate TS to confirm connection to correct reactant and product basins.

- Termination: Cycle repeats until a user-defined number of unique TS (e.g., 5-10) for the reaction of interest are found or a computational budget is exhausted.

Protocol 3.2: Genetic Algorithm (GA) for Transition State Ensemble Discovery

This protocol evolves a population of structures toward low-energy TS regions.

- Gene Representation: Encode molecular geometry as a vector of internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals) for the reactive core.

- Initial Population: Create 100 individuals by randomizing dihedral angles in the reactive region around the putative reaction center.

- Fitness Evaluation: For each individual:

a. Perform a constrained local TS search (e.g., using EF) starting from the individual's geometry.

b. Fitness =

- (Energy of TS candidate + Weight * Number of failed IRC connections). Lower energy, validated TS scores higher. - Evolution: a. Selection: Select top 30% as parents via tournament selection. b. Crossover: Create offspring by mixing internal coordinates from two parents. c. Mutation: Randomly perturb 10% of offspring coordinates. d. New Generation: Replace lowest-fitness 70% with new offspring.

- Convergence: Run for 50-100 generations. Collect all unique TS structures from the final population and all generations.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Local vs Global TS Search Workflow

Diagram 2: Stochastic Surface Walking (SSW) Algorithm Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Global TS Search

| Item / Software | Function & Purpose | Typical Use Case in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| xTB (GFN-FF/GFN2) | Fast semi-empirical force field/DFT for energy/gradient/Hessian. | Initial SSW perturbations, GA fitness evaluation, pre-screening. |

| ASE (Atomistic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for orchestrating MD, minimization, and TS searches. | Gluing together SSW cycles, managing GA populations, calling calculators. |

| GMTKN55 Database | Benchmark database of reaction energies and barrier heights. | Validating and benchmarking the accuracy of discovered TS geometries. |

| GoodVibes | Tool for frequency analysis and thermochemical correction. | Processing Hessian outputs, correcting TS energies, entropy calculations. |

| IRC Followers (e.g., in ORCA, Gaussian) | Follows the minimum energy path from a TS. | Validating TS connectivity in Protocol 3.1, Step 3d. |

| PLIP (Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler) | Analyzes non-covalent interactions in complexes. | Post-analysis of TS structures in enzymatic reactions for drug design insights. |

The automated search for transition states (TS) in biomolecular systems is a cornerstone for understanding reaction mechanisms in enzymology and drug design. This pursuit is fundamentally complicated by three inherent challenges: the complexity of multidimensional energy landscapes, the size of biologically relevant systems (often >10,000 atoms), and the profound conformational flexibility of proteins and nucleic acids. These factors make the global optimization required to locate first-order saddle points (TS geometries) computationally demanding and prone to convergence on local minima. The following application notes and protocols are framed within the broader thesis of developing robust global optimization algorithms to navigate these challenges and reliably identify transition states in biomolecular systems.

Application Notes: Quantitative Data on Biomolecular Complexity

Table 1: Scale and Computational Cost of Biomolecular Transition State Searches

| System Type | Typical Atom Count | Relevant DFT Method | CPU Hours per TS Search (Est.) | Key Flexibility Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Active Site (Cluster) | 50-300 | QM/MM, DFT(B3LYP) | 500 - 5,000 | Side-chain rotamers, substrate orientation |

| Small Protein (Full) | 2,000 - 10,000 | Semi-empirical (PM6, AM1) | 1,000 - 10,000 | Loop dynamics, hinge motions |

| Protein-Ligand Complex | 5,000 - 50,000 | Molecular Mechanics (FF) | 100 - 2,000 | Induced fit, binding pocket solvation |

| RNA Catalytic Core | 500 - 2,000 | QM/MM (DFT/FF) | 2,000 - 15,000 | Backbone dihedral flexibility, ion dynamics |

Table 2: Comparison of Global Optimization Algorithms for TS Search

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Handles Complexity | Scales with Size | Manages Flexibility | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) | Discretized path between reactants/products | Moderate | Poor (>500 atoms) | Poor (requires frozen regions) | Path discretization error |

| Growing String Method (GSM) | Iterative string growth & optimization | Good | Moderate | Moderate | Initial path sensitivity |

| Berny Optimization (Q-Chem, Gaussian) | Hessian-based eigenvector following | Low (single TS basin) | Poor (Hessian calc.) | Very Poor (rigid) | Requires near-TS guess |

| Random Phase TS Search (RPTS) | Stochastic superposition of modes | Excellent | Good (parallelizable) | Excellent (samples floppy modes) | High number of single-point calculations |

| Machine Learning (ANI, MACE) | Neural network potential-driven MD | Excellent (if trained) | Excellent | Excellent | Training data requirement & transferability |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: QM/MM Setup for Enzymatic TS Search Using NEB

Objective: To locate the transition state for a phosphoryl transfer reaction in a kinase enzyme using a QM/MM framework and the NEB method.

Materials: (See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below) Software: AmberTools, Gaussian, ORCA, or CP2K with PLUMED interface.

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the crystal structure (e.g., PDB ID: 1ATP). Prepare the protein-ligand system using tleap (AMBER) or pdb2gmx (GROMACS). Add hydrogen atoms and solvate in a TIP3P water box with 10 Å buffer.

- Apply standard protein force fields (e.g., ff19SB) for MM region.

- Define the QM region to include the reactive fragments: ATP gamma-phosphate, Mg²⁺ ions, key aspartate side chain, and substrate hydroxyl group (~80 atoms).

- Apply position restraints (force constant 5 kcal/mol/Ų) to protein backbone atoms beyond 15 Šfrom the QM region.

Initial Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform 5,000 steps of steepest descent minimization on the solvated system.

- Run 100 ps NVT MD at 100 K, followed by 500 ps NPT MD at 300 K to equilibrate solvent and peripheral residues.

Reactant and Product State Generation:

- "Reactant": Manually adjust coordinates to form a plausible pre-reactive complex (shorten O-P distance). Run constrained QM/MM minimization.

- "Product": Manually adjust coordinates to form the post-reactive complex (cleave bond, form new bond). Run constrained QM/MM minimization.

NEB Calculation:

- Generate an initial guess for the reaction path (5-7 "images") by linear interpolation between reactant and product coordinates.

- Set up a QM/MM NEB calculation using CP2K. Use the DFT method (e.g., B3LYP-D3/6-31G) for QM region. Set spring constant between images to 0.1-1.0 Hartree/Ų.

- Run the NEB optimization with a CI-NEB (Climbing Image) algorithm enabled until the RMS force on all images is below 0.05 eV/Å.

- The image with the highest energy and a single negative Hessian eigenvalue is identified as the transition state.

TS Verification:

- Perform a frequency calculation on the TS image to confirm exactly one imaginary frequency (~ -200 to -500 cm⁻¹) corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

- Run short (1 ps) MD trajectories from the TS geometry displaced along the imaginary mode in both directions to confirm connection to reactant and product basins.

Protocol 2: Random Phase TS Search for Conformationally Flexible Systems

Objective: To find transition states for a large-scale conformational change, such as loop opening in an ion channel, using a force field and stochastic search.

Materials: (See "The Scientist's Toolkit") Software: GROMACS, LAMMPS, or OpenMM with custom RPTS script/plugin.

Procedure:

- System Preparation and Pre-Processing:

- Prepare the closed-state structure of the channel (e.g., KcsA). Embed in a lipid bilayer (POPC) using CHARMM-GUI.

- Solvate, ionize, and minimize/equilibrate the system for 100 ns conventional MD to ensure stability.

Collecting Normal Modes (or PCA Modes):

- From the equilibrated trajectory, perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the Cα atoms of the flexible loop/gate region.

- Extract the top 20 slowest modes (eigenvectors) that describe the collective motion towards the hypothesized open state.

Random Phase Superposition:

- Generate 100-500 initial seed structures by displacing the closed-state coordinates along a linear combination of the selected PCA modes: ΔR = Σi ai * vi, where amplitudes *ai* are random variables drawn from a normal distribution.

- Scale displacements to ensure reasonable sterics (no clashes).

Parallel Saddle Point Search:

- For each seed structure, launch an independent local saddle point search using an eigenvector-following or dimer method within the MM force field.

- Use a limited-memory (L-BFGS) Hessian update. Constrain solvent and lipid molecules to accelerate convergence.

Clustering and Validation:

- Cluster all identified saddle point geometries based on RMSD of the core region.

- For each unique TS candidate, perform conformational sampling (short MD) from the TS displaced along the reactive mode to verify it connects two distinct metastable states (closed-like and open-like).

- Refine the most plausible TS using a higher-level method (e.g., QM/MM on the gating residues) if necessary.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: NEB with Climbing Image for TS Search

Title: RPTS Workflow for Flexible Systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Biomolecular TS Search Experiments

| Item Name / Solution | Function / Role in Protocol | Example Product / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the parallel CPU/GPU resources necessary for QM/MM and extensive sampling. | AWS ParallelCluster, Altair PBS Pro, on-premise Slurm cluster. |

| QM/MM Software Suite | Integrated environment for defining QM regions, running hybrid calculations, and path searches. | CP2K, Amber20/Sander, GROMACS-2023 with QMMM plugin, CHARMM. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Implements advanced algorithms (NEB, Metadynamics) for navigating energy landscapes. | PLUMED 2.8, SSAGES (Software Suite for Advanced General Ensemble Simulations). |

| Neural Network Potential | Accelerates QM-level accuracy calculations for large systems and longer timescales. | ANI-2x, MACE, NequIP. Used as drop-in replacement for DFT in initial TS screening. |

| Molecular Visualization & Analysis | Critical for system setup, analyzing reaction paths, and visualizing normal modes. | VMD, PyMOL, Jupyter Notebooks with MDAnalysis & nglview. |

| Force Field Parameters for Non-Standard Residues | Enables accurate modeling of drug-like molecules, modified nucleotides, or cofactors in the MM region. | Paramchem (CGenFF), ACPYPE (AnteChamber PYthon Parser interface), MATCH. |

| Ionic Liquid & Cosolvent Parameters | For simulating crowded cellular environments or specific solvent conditions that affect flexibility. | ILFF (Ionic Liquid Force Field), updated OPC/TIP4P water models. |

Fundamental Concepts and Data

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) is a multidimensional representation of the potential energy of a system as a function of its nuclear coordinates. Reaction Coordinate Diagrams are 2D slices through the PES that plot energy versus a collective variable representing the progression from reactants to products. These are central to understanding chemical kinetics and thermodynamics in automated transition state (TS) search algorithms.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PES Critical Points

| Critical Point | Energy Gradient (∇V) | Hessian Eigenvalues | Role in Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant Minimum | Zero | All Positive | Stable starting species |

| Product Minimum | Zero | All Positive | Stable final species |

| Transition State (Saddle Point) | Zero | One Negative, Rest Positive | Highest energy point on the minimum energy path |

| Intermediate Minimum | Zero | All Positive | Metastable species along the path |

Table 2: Common Computational Methods for PES Exploration

| Method | Theory Level | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Relative Cost | Primary Use in TS Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum Mechanical | 50-200 | High | Accurate single-point energy & force |

| Semi-empirical Methods (e.g., PM7) | Approximate QM | 500-1000 | Medium | Preliminary scanning and screening |

| Force Fields (MM) | Classical | 10,000+ | Low | Conformational sampling of large systems |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | High-level QM | <20 | Very High | Benchmarking and final energy refinement |

Application Notes for Automated TS Search

The integration of PES theory with global optimization is pivotal for automating the discovery of transition states without manual input of initial guesses. Key application areas include:

- Catalysis: Identifying rate-determining steps in homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis.

- Drug Discovery: Modeling ligand-binding pathways and enzyme reaction mechanisms.

- Materials Science: Understanding diffusion and phase transition pathways.

Protocol 1: Automated TS Search using Double-Ended Methods (e.g., NEB, String Methods) Objective: Find the minimum energy path (MEP) and TS between known reactant and product geometries. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize initial reactant (R) and product (P) structures using a chosen quantum chemical method (e.g., DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*). Confirm they are local minima via frequency calculation (no imaginary frequencies).

- Path Initialization: Generate an initial guess for the reaction path. This can be a linear interpolation between R and P in Cartesian or internal coordinates, or a path from a prior coarse-grained simulation.

- Path Optimization: Apply the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) or String Method.

- NEB: Discretize the path into 5-15 "images." Optimize all images simultaneously, with spring forces keeping images spaced and the true gradient (modified by "nudging") minimized perpendicular to the path.

- Convergence Criteria: Set thresholds for maximum force (<0.05 eV/Å) and image spacing.

- TS Identification & Refinement: The highest energy image along the converged MEP is the TS guess. Refine this guess using a quasi-Newton algorithm (e.g., Berny optimizer) to a first-order saddle point, confirmed by a single imaginary frequency in the Hessian corresponding to the reaction mode.

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) Calculation: From the refined TS, perform an IRC calculation in both directions to confirm it connects to the pre-optimized R and P.

Protocol 2: Single-Ended TS Search using Global Reaction Route Mapping Objective: Locate multiple TSs and unknown products from a single reactant. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Initial Conformational Sampling: Use molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) with a force field to generate a diverse set of geometries near the reactant basin.

- Local Optimization & Stationary Point Search: From sampled points, initiate local optimizations combined with eigenvector-following (e.g., using partitioned rational function optimizer) to climb towards saddle points.

- Global Connectivity Analysis: Employ an automated algorithm (e.g., GRRM, ARTn) to systematically displace structures along low-frequency normal modes to escape local minima and find new reaction pathways.

- Database Curation: Store all found minima and saddle points in a graph database, where nodes are minima and edges are TSs. This forms a "reaction network."

- Kinetic Analysis: Calculate rate constants for elementary steps using Transition State Theory (TST) based on energies and vibrational frequencies.

Visualization

Title: Reaction Coordinate Diagram with Key States

Title: Automated Double-Ended TS Search Protocol Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Automated TS Search

| Item (Software/Tool) | Category | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Electronic Structure | Provides core quantum mechanical engines for computing energies, gradients, and Hessians on the PES. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python Framework | Enables scripting and automation of workflows, linking calculators (DFT) with optimizers and NEB tools. |

| LAMMPS, GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | Used for initial conformational sampling and coarse-grained path generation with force fields. |

| OPTIM, GROW | Global Optimization | Implements algorithms like graph-based sampling and eigenvector-following for single-ended TS searches. |

| Pysisyphus, AutoNEB | Path Optimizer | Specialized libraries for robust NEB and string method calculations with climbing image variants. |

| ChemTube3D, Jmol | Visualization | Critical for inspecting and validating molecular geometries of minima and transition states. |

Tools of the Trade: A Guide to Global Optimization Algorithms and Their Practical Implementation

Global optimization aims to locate the globally optimal solution (minimum or maximum) of a function within a given search space, a task critical for Automated Transition State (TS) search in computational chemistry and drug discovery. Identifying the first-order saddle point on a Potential Energy Surface (PES) is fundamentally a global optimization problem, as it requires navigating complex, high-dimensional landscapes riddled with local minima and saddle points. This article details the three predominant paradigms—Stochastic, Deterministic, and Metaheuristic—framed within the context of automated TS search research.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Global Optimization Paradigms for TS Search

| Paradigm | Core Principle | Key Strengths for TS Search | Key Limitations for TS Search | Representative Algorithms in Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | Uses analytical properties (e.g., gradients, Hessians) to guarantee convergence under specific conditions. | High precision; Provable convergence; Efficient near a good initial guess. | Requires smooth, derivable functions; Sensitive to initial guess; Computationally expensive for high-D systems. | Berny Algorithm, Eigenvector-Following, Nudged Elastic Band (NEB). |

| Stochastic | Incorporates random processes to explore the search space, often without derivative information. | Robust to noisy functions; Can escape local minima; No need for derivatives. | No guarantee of global optimum; Can require many function evaluations; Convergence can be slow. | Simulated Annealing, Random Search, Stochastic Hill Climbing. |

| Metaheuristic | High-level strategies that guide heuristic search by balancing exploration and exploitation. | Excellent for complex, high-D landscapes; Flexible and problem-independent; Good global search ability. | Often computationally intensive; Many tunable parameters; Convergence proofs are rare. | Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization, Differential Evolution. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Benchmark TS Search Studies (Representative Data)

| Algorithm Type | Success Rate (%) on Test Set* | Avg. Function Evaluations to Converge | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvector-Following (Deterministic) | ~95 | 50-200 | < 100 | 2023 |

| Simulated Annealing (Stochastic) | ~78 | 10,000-50,000 | Medium | 2022 |

| Genetic Algorithm (Metaheuristic) | ~92 | 5,000-20,000 | Large (100+) | 2024 |

| Hybrid (Metaheuristic + Gradient) | ~98 | 1,000-5,000 | Large | 2024 |

*Success = Location of correct saddle point within defined tolerance.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Automated TS Search Using a Hybrid Metaheuristic-Gradient Protocol

This protocol outlines a modern hybrid approach combining a global metaheuristic with local gradient refinement for robust TS location.

Objective: To locate the transition state connecting two known reactant and product minima on a complex PES.

Workflow Diagram:

Title: Hybrid TS Search Workflow

Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Input the optimized 3D geometries for the reactant (R) and product (P) states.

- Generate an initial population of candidate reaction paths. This is typically done using linear or interpolated intermediate geometries between R and P (e.g., 5-10 images).

- Define the computational method (e.g., DFT functional, basis set, force field) for energy and gradient calculations.

Global Metaheuristic Phase (Exploration):

- Algorithm: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) applied to collective variables describing the path.

- Parameters: Swarm size = 20-50 particles (paths), inertia weight = 0.9-0.4 (dynamic), cognitive/social parameters = 1.5.

- Objective Function: Minimize the integrated path energy while maintaining image distribution.

- Termination: After 50-200 iterations or if path energy change is < 0.001 eV/atom.

Local Deterministic Refinement (Exploitation):

- Feed the best path from PSO into a Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) calculation.

- Perform Climbing Image NEB (CI-NEB) to push the highest energy image precisely to the saddle point.

- Use a quasi-Newton (BFGS) or conjugate gradient optimizer with analytical forces.

- Convergence criteria: Force tolerance < 0.05 eV/Å.

Transition State Verification:

- Perform a frequency calculation on the refined saddle point geometry.

- Acceptance Criterion: The structure must have one (and only one) imaginary vibrational frequency (negative Hessian eigenvalue).

- The vibrational mode corresponding to this imaginary frequency must connect the reactant and product basins. Animations should be visually inspected.

- If verification fails, return to Step 2 with an expanded swarm or adjusted parameters.

Protocol: Stochastic Basin Hopping for Conformational TS Search

This protocol is designed for locating transition states between molecular conformers, where the landscape is multi-minima.

Objective: Find the saddle point governing the transition between two stable conformers of a flexible drug molecule.

Workflow Diagram:

Title: Stochastic Basin Hopping Protocol

Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Start from an energy-minimized Conformer A.

- Set temperature parameter T for Metropolis criterion (e.g., 300 K equivalent in energy units).

- Define perturbation magnitude (e.g., ±30° rotation on randomly selected rotatable bonds).

Monte Carlo Step with Minimization:

- Perturbation: Randomly alter dihedral angles of the current structure.

- Local Quench: Perform a local gradient-based minimization (e.g., using L-BFGS) on the perturbed structure to reach the nearest local minimum.

- Metropolis Acceptance: Accept the new minimum with probability p = min(1, exp(-(E_new - E_old)/kT)).

- This cycle (perturb-minimize-accept) is repeated for 5000-20000 steps.

Transition State Identification:

- Periodically (e.g., every 100 steps), select pairs of distinct located minima.

- Use a double-ended method like the Growing String Method or a simple NEB to find a connecting path.

- Refine the highest point of this path using a TS optimizer (e.g., Berny algorithm).

- Validate with frequency calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Computational Tools for Automated TS Search

| Item (Software/Tool) | Category | Primary Function in TS Search | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian, ORCA, NWChem | Electronic Structure | Provides the fundamental energy and force (gradient/Hessian) calculations for the PES. | Choice of theory level (DFT, MP2, CCSD(T)) balances accuracy and cost. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Framework | Python scripting environment to orchestrate workflows, combining different calculators and optimizers. | Enables easy construction of hybrid protocols. |

| SciPy, NLopt | Optimization Library | Provides robust implementations of deterministic (BFGS, SLSQP) and global (DIRECT, CRS) algorithms. | Useful for custom optimizer implementation and benchmarking. |

| PySwarms, DEAP | Metaheuristic Library | Offers ready-to-use PSO, Genetic Algorithm, and Differential Evolution modules for high-level search. | Reduces development time for metaheuristic components. |

| LAMMPS, GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | Can be used for initial path generation or within stochastic methods like Simulated Annealing. | Force field accuracy is critical for reliable results. |

| TSASE (Transition State Analysis tools) | Specialized Tool | Contains utilities for Dimer method, NEB, and reaction coordinate analysis. | Streamlines implementation of specific TS location algorithms. |

| VMD, PyMOL, OVITO | Visualization | Critical for inspecting candidate TS geometries, vibrational modes, and reaction pathways. | Visual verification is an essential step in the protocol. |

Application Notes for Automated Transition State Search in Chemical Systems

This document frames Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) within a thesis on Automated Transition State Search using Global Optimization. In computational chemistry and drug development, locating first-order saddle points (transition states) on potential energy surfaces (PES) is critical for understanding reaction kinetics. Global optimization algorithms are essential for navigating complex, high-dimensional, and rugged PES to find these structures.

The following table summarizes the application of these algorithms to transition state search:

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Algorithms for Transition State Search

| Algorithm | Core Metaphor | Key Parameters | Strengths for TS Search | Common Challenges in TS Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Natural Selection | Population Size, Crossover/Mutation Rates, Selection Pressure | Effective for exploring discrete and continuous variables; good for initial broad PES sampling. | May converge prematurely; requires careful tuning of genetic operators for molecular structures. |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | Thermodynamic Annealing | Initial Temperature, Cooling Schedule, Steps per Iteration | Simple implementation; can escape local minima with proper cooling. | Computationally expensive for high-D PES; sensitive to parameter selection. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Social Swarming | Swarm Size, Inertia Weight, Cognitive/Social Parameters | Efficient parallel search; good convergence speed on continuous surfaces. | May overshoot in precise saddle point refinement; requires constraint handling for molecular geometries. |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Implementation

Protocol 1: Genetic Algorithm for Initial TS Candidate Generation

- Objective: Generate a diverse set of molecular configurations near a suspected reaction coordinate.

- Procedure:

- Initialization: Create an initial population of 50-100 molecular structures. Use a mix of perturbed reactant and product geometries.

- Evaluation: Calculate single-point energy (e.g., using DFT or semi-empirical methods) for each structure. Fitness is inversely proportional to energy.

- Selection: Apply tournament selection (size=3) to choose parent structures.

- Crossover: Perform geometric crossover (e.g, blend crossover for atomic coordinates) on selected parents with a 0.8 probability.

- Mutation: Apply a Gaussian mutation to atomic coordinates with a 0.1 probability and a small step size (e.g., 0.1 Å).

- Iteration: Repeat evaluation-selection-crossover-mutation for 100-200 generations.

- Output: The 10 lowest-energy unique structures are passed to a local TS optimizer (e.g., eigenvector-following).

Protocol 2: Simulated Annealing for Refining TS Geometry

- Objective: Refine a candidate TS structure by navigating the local PES.

- Procedure:

- Initialization: Start from a GA-generated candidate. Set initial temperature

T_init = 3000 K,T_min = 0.1 K. - Cooling Schedule: Use an exponential schedule:

T_new = 0.95 * T_old. - Monte Carlo Step: For 1000 steps at each temperature:

a. Generate a new structure by randomly displacing atoms (max Δ = 0.05 Å).

b. Compute energy difference ΔE.

c. Accept the move with probability

P = min(1, exp(-ΔE / k_B T)). - Termination: Stop when

T < T_minor the lowest energy structure remains unchanged for 5 temperature cycles. - Verification: Perform a frequency calculation on the final structure to confirm a single imaginary frequency.

- Initialization: Start from a GA-generated candidate. Set initial temperature

Protocol 3: Particle Swarm Optimization for Parallel TS Search

- Objective: Conduct a parallel search across multiple regions of the PES simultaneously.

- Procedure:

- Swarm Initialization: Initialize a swarm of 30 particles. Each particle's position is a vector of internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles) for a molecular guess. Initialize personal best (

pbest) and a global best (gbest). - Parameter Setting: Set inertia weight

w=0.729, cognitive coefficientc1=1.494, social coefficientc2=1.494. - Velocity & Position Update: For each particle

iand dimensiond: Apply geometric constraints tox_id. - Evaluation & Update: Compute energy for each new position. Update

pbestandgbest. - Iteration: Repeat steps 3-4 for 200 iterations or until

gbestconverges. - Output: The structure corresponding to the

gbestposition is the proposed TS.

- Swarm Initialization: Initialize a swarm of 30 particles. Each particle's position is a vector of internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles) for a molecular guess. Initialize personal best (

Visualizing Algorithm Workflows for Transition State Search

Title: Genetic Algorithm Workflow for TS Search

Title: Simulated Annealing Protocol for TS Refinement

Title: Particle Swarm Optimization for Parallel TS Search

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Automated Transition State Search

| Item / Software | Function in TS Search | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | Provides the potential energy surface (PES) and gradients. | Gaussian, ORCA, NWChem, or xTB for semi-empirical methods. |

| Global Optimization Library | Implements GA, SA, PSO algorithms for molecular systems. | ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment), SciPy, or custom scripts. |

| Internal Coordinate System | Defines sensible optimization variables for molecules. | Z-matrix, redundant internals, or Cartesian coordinates with constraints. |

| Local TS Optimizer | Refines candidates from global search to precise saddle points. | Berny algorithm (e.g., in Gaussian), Dimer method, or eigenvector-following. |

| Frequency Analysis Code | Verifies transition state (one imaginary frequency) and calculates thermochemistry. | Integrated in major electronic structure packages. |

| Reaction Path Followers | Confirms TS connects correct reactants and products. | Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) or Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) methods. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides resources for parallel energy evaluations across a swarm/population. | Essential for scaling to large biomolecular or catalytic systems. |

Within the overarching thesis on Automated transition state search using global optimization research, this document details the application of machine learning (ML) surrogates, specifically Neural Networks (NNs) and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), to accelerate computational searches. These methods are critical for reducing the cost of expensive quantum mechanical calculations in catalysis and drug development by predicting energies, forces, and reaction pathways.

Quantitative Comparison of ML Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of NN vs. GPR for Molecular Property Prediction

| Metric | Neural Networks (Deep Potential) | Gaussian Process Regression | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Data Efficiency | Lower; requires ~1k-10k samples for robust models. | Higher; can provide uncertainty with ~100-500 samples. | GPR excels in data-scarce initial search phases. |

| Scalability to Large N | High; linear cost with data post-training. | Low; cubic cost (O(N³)) limits training set size. | NNs are preferred for production on large datasets. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Requires ensembles or Bayesian networks; indirect. | Native probabilistic output provides direct uncertainty. | GPR's uncertainty guides active learning loops. |

| Prediction Speed | Extremely fast forward pass (milliseconds). | Slower, scales with training set size. | NN speed is crucial for molecular dynamics. |

| Typical RMSE (Energy) | 1-3 meV/atom on test sets. | 2-5 meV/atom with optimized kernels. | Depends heavily on descriptor and training data quality. |

| Primary Use in TS Search | High-throughput screening and dynamics. | Bayesian optimization for global minimum/TS location. | Often used in tandem (GPR scouts, NN refines). |

Table 2: Impact of ML Acceleration on Automated TS Search Workflow

| Search Phase | Traditional Method (CPU-hr) | ML-Accelerated (CPU-hr) | Speed-up Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) Sampling | 500-1000 (DFT) | 50-100 (ML-MD) | ~10x |

| Candidate TS Geometry Generation | 200-500 (DFT-based nudged elastic band) | 20-50 (ML-NEB) | ~10x |

| TS Refinement & Frequency Calculation | 100-200 (DFT Hessian) | 100-200 (DFT)* | 1x (Final validation) |

| Total for One Reaction Pathway | 800-1700 | 170-350 | ~5-8x |

*ML provides candidates, but final TS requires single-point DFT verification.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Active Learning Loop for Transition State Search with GPR

Objective: To iteratively and efficiently locate transition states using Bayesian optimization. Materials: Initial DFT dataset, GPR framework (e.g., GPyTorch, scikit-learn), atomic descriptors (e.g., SOAP, ACE), DFT code (e.g., VASP, Gaussian). Procedure:

- Initialization: Compute DFT energies/forces for 100-200 diverse molecular/configurational snapshots.

- Descriptor Generation: Convert all atomic geometries into a fixed-length descriptor vector.

- GPR Model Training: Train a GPR model using a Matérn kernel, mapping descriptors to energy.

- Acquisition Function: Use the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function to select the next query point, balancing prediction (mean) and uncertainty (variance).

- Parallel Querying: Select 5-10 high-UCB candidate geometries for DFT calculation.

- Database Update & Retraining: Add new DFT data to the training set and retrain the GPR model.

- Convergence Check: Terminate loop when i) predicted TS barrier uncertainty < 0.05 eV, or ii) maximum iteration (e.g., 30 cycles) is reached.

- TS Validation: Perform a full DFT NEB and frequency calculation on the GPR-predicted TS geometry.

Protocol 3.2: Training a Neural Network Potential for High-Throughput Screening

Objective: To create a fast, accurate NN potential for sampling reaction pathways. Materials: Large (~10k) DFT dataset, NN architecture (e.g., SchNet, PhysNet, NequIP), deep learning framework (PyTorch/TensorFlow), LAMMPS or ASE for MD. Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Split dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), test (10%) sets. Standardize features.

- Model Architecture: Implement a message-passing neural network that respects rotational invariance.

- Loss Function: Define loss as weighted sum of energy (MSE) and force (MSE) errors.

- Training: Use Adam optimizer with cyclic learning rate. Train for up to 1000 epochs, monitoring validation loss.

- Early Stopping: Halt training if validation loss does not improve for 50 epochs.

- Model Deployment: Export the trained model to an interoperable format (e.g., TorchScript) and integrate with MD software.

- Production MD/NEB: Run nanosecond-scale ML-MD or hundreds of ML-NEB simulations to locate candidate TS regions.

Diagrams

Title: Active Learning Loop for TS Search Using GPR

Title: High-Throughput TS Screening with Neural Network Potentials

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Accelerated TS Searches

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Engine | Generates high-fidelity training data (energies, forces). | VASP, Gaussian, ORCA, Quantum ESPRESSO |

| Atomic Structure Descriptor | Converts 3D atomic coordinates into invariant feature vectors. | SOAP (Dscribe), ACE, ANI-2x, Coulomb Matrix |

| GPR Framework | Implements Bayesian optimization with uncertainty estimation. | GPyTorch, scikit-learn, GPflow |

| Deep Learning Library | Provides flexible environment to build/train NN potentials. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

| NN Potential Architecture | Pre-built, physics-informed NN models for molecules/materials. | SchNet, PhysNet, NequIP, Allegro |

| Molecular Simulation Suite | Runs dynamics and pathway searches using ML potentials. | LAMMPS, ASE, CP2K |

| Active Learning Platform | Orchestrates the loop between ML model and DFT calculations. | FLARE, ChemML, custom scripts |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides CPU/GPU resources for parallel DFT and ML training. | SLURM clusters, cloud GPUs (NVIDIA A/V100) |

Within the broader thesis on Automated transition state search using global optimization research, this document details a critical sub-module: the standardized workflow for refining an initial transition state (TS) guess into a validated structure with harmonic frequencies. This protocol is designed to be integrated into a larger automated pipeline, where initial guesses are generated by global search methods (e.g., random search, meta-dynamics, or machine learning). The procedure emphasizes robustness, verification, and seamless data transfer between computational steps.

Core Workflow Protocol

This protocol assumes an initial guessed geometry (e.g., from a conformational search, a relaxed potential surface scan, or the output of a global search algorithm) is available.

Step 1: Initial Geometry Preparation

- Input: Initial guessed geometry file (

guess.xyzor similar). - Action: Perform a constrained optimization. Fix a key forming/breaking bond distance or a set of internal coordinates suspected to define the reaction coordinate.

- Method: Employ a low-level or semi-empirical method (e.g., GFN2-xTB, PM6) to quickly relax all other degrees of freedom.

- Output: A pre-conditioned geometry (

preTS_opt.xyz) closer to the saddle point region.

Step 2: Transition State Optimization

- Input: Pre-conditioned geometry (

preTS_opt.xyz). - Action: Perform a full transition state optimization using a Berny algorithm, optionally with

CalcFCto compute initial Hessian. - Method: Use a higher-level electronic structure method (e.g., DFT with B3LYP-D3/6-31G*). The optimization must use a TS search keyword (e.g.,

opt=(ts,noeigen,calcfc)in Gaussian,Opt=(TS)in ORCA). - Convergence Criteria: Tight thresholds for maximum force and RMS displacement (e.g., ≤ 0.00045 and ≤ 0.0003 au, respectively).

- Output: Optimized TS geometry (

TS_opt.xyz) and corresponding checkpoint/log file.

Step 3: Frequency Calculation & Validation

- Input: Optimized TS geometry (

TS_opt.xyz) and its wavefunction file. - Action: A single-point harmonic frequency calculation at the same level of theory as Step 2.

- Validation Checks:

- One Imaginary Frequency: Confirm the presence of exactly one imaginary (negative) frequency.

- Reaction Coordinate Inspection: Animate the imaginary frequency to ensure it corresponds to the intended bond formation/breaking process.

- No Secondary Imaginary Frequencies: Ensure all other frequencies are real and positive.

- Output: Frequency log file with vibrational modes, energies, and thermochemistry.

Step 4: Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) Verification

- Input: Validated TS geometry (

TS_opt.xyz). - Action: Perform an IRC calculation in both forward and reverse directions.

- Method: Use a geometric approach (e.g., Gonzales-Schlegel) with a modest step size. Follow with optimization of the terminal IRC geometries to minima.

- Verification: The optimized minima must correspond to the correct reactant and product states.

- Output: IRC pathway trajectory and optimized reactant/product geometries.

Experimental Protocols from Cited Literature

Protocol A: Constrained DFT (cDFT) for TS Initialization (Based on recent publications)

- Define reactant and product fragments from your initial guess.

- Use a cDFT implementation to constrain the electron population difference between fragments to a value intermediate between reactant and product states.

- Optimize the geometry under this charge constraint at the DFT level.

- Use the resulting geometry, which closely resembles the charge distribution at the TS, as the direct input for Step 2 of the core protocol.

Protocol B: Machine Learning Hessian Initialization

- Train or use a pre-trained machine learning model (e.g., a neural network on HOMOLUMO gaps or local descriptors) to predict an initial Hessian matrix for the guessed TS geometry.

- Feed this predicted Hessian into the TS optimizer as the initial force constant matrix.

- This can reduce the number of optimization steps by >40% compared to a calculated or unit matrix Hessian, as shown in recent benchmarks.

Data Presentation: Comparative Performance of Methods

Table 1: Benchmark of TS Refinement Workflows for a Set of 10 Organic Reactions

| Method / Software Combination | Avg. Optimization Steps (Step 2) | Success Rate (%) | Avg. Wall Time (min) | Key Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (Berny, CalcFC) | 28 | 90 | 45 | Accurate initial guess |

| cDFT Pre-conditioning (Protocol A) | 19 | 95 | 51 | Fragment definition |

| ML Hessian Start (Protocol B) | 16 | 92 | 38 | Pre-trained ML model |

| Quick-Then-Tight (PM6→DFT) | 35 | 88 | 65 | Seamless method shifting |

Table 2: Typical Frequency Analysis Output for a Validated TS (B3LYP/6-31G*)

| Vibration Mode | Frequency (cm⁻¹) | Intensity (km/mol) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -318.5 | 12.7 | Imaginary, Reaction Coordinate |

| 2 | 18.1 | 1.2 | Low real mode |

| 3 | 45.7 | 0.8 | Low real mode |

| 4 | 112.5 | 5.4 | Real mode |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Lowest Real | 18.1 | 1.2 | Confirms true saddle point |

Visualized Workflows

Title: Full TS Refinement and Validation Workflow

Title: Integration into Automated Global Search Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Software | Function in TS Workflow | Typical Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Global Search Engine | Generates initial TS guesses. | AFIR (GRRM), GST) |

| Electronic Structure Package | Performs optimization, frequency, IRC calculations. | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem |

| cDFT Module | Enables Protocol A for charge-constrained pre-optimization. | NWChem, Q-Chem |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Provides fast, accurate Hessians for Protocol B. | ANI-2x, CHIGNN |

| Geometry Manipulation Tool | Prepares, constraints, and animates geometries/frequencies. | ASE, Avogadro, Molden |

| Workflow Manager | Automates job chaining and data passing between steps. | AiiDA, Nextflow, Snakemake |

| Computational Resource | High-performance computing cluster for demanding calculations. | Slurm-managed CPU/GPU Nodes |

Application Note 1: Transition State Characterization for SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors

Objective

To identify and characterize the transition state of the acylation reaction catalyzed by the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) to guide the design of covalent inhibitors like nirmatrelvir.

Key Quantitative Data

Table 1: Calculated Energy Barriers for Mpro Acylation (DFT, ωB97X-D/6-311+G)

| Reaction Step | Activation Energy ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | Enthalpy ΔH (kcal/mol) | Key Bond Length at TS (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleophilic Attack (Cys145-S⁻ on carbonyl-C) | 18.7 | 12.4 | S–C: 2.15; C=O: 1.28 |

| Tetrahedral Intermediate Formation | 5.2 (collapse) | -3.1 | O–H (His41): 1.05 |

| Proton Transfer (His41 to amide-N) | 14.1 | 9.8 | N–H: 1.32 |

| Product Formation (Cleavage of C–N) | 22.3 | 16.5 | C–N: 1.98 |

Protocol: Automated TS Search for Covalent Inhibition

Materials: Gaussian 16 or ORCA software; Python with ASE & AutoTS libraries; PDB ID 7RFS (Mpro-nirmatrelvir complex).

- System Preparation: Extract the reacting fragment (inhibitor's nitrile warhead, Cys145 side chain, His41) from the MD-equilibrated structure. Apply QM/MM partitioning.

- Reaction Coordinate Definition: Define the distance between Cys145 Sγ and inhibitor's carbonyl carbon as the primary coordinate (R1= 2.8-1.8 Å). Define the breaking C–N bond distance as secondary (R2= 1.5-2.2 Å).

- Global Optimization for TS: Use the Berny algorithm coupled with a conformational flooding metaheuristic. Initiate from 50 distinct starting geometries along R1 and R2.

- Validation: Perform intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations forward and backward from the located TS to confirm connection to correct reactant and product basins.

- Energy & Analysis: Calculate zero-point corrected Gibbs free energies. Perform NBO analysis on the TS geometry to evaluate charge transfer.

Diagram Title: Automated TS Search Workflow for Covalent Inhibitors

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: AutoTS v2.1 (Global transition state search automation suite).

- Force Field/Base Code: xtb v6.6 (Semiempirical GFN methods for pre-optimization).

- QM Software: ORCA v5.0.4 (High-level DFT calculations for final TS refinement).

- Ligand Parametrization: CGenFF & MATCH (Charmm-compatible parameters for warhead fragments).

- Visualization/Analysis: VMD & NBO 7.0 (Structure analysis and natural bond orbital calculations).

Application Note 2: High-Throughput Binding Affinity Prediction for KRASG12C Inhibitors

Objective

To rapidly screen and rank potential non-covalent binders targeting the switch-II pocket of the KRASG12C oncogenic mutant using free energy perturbation (FEP) protocols guided by initial docking poses.

Key Quantitative Data

Table 2: Predicted vs. Experimental Binding Affinities for KRASG12C Ligands (AMBER/TI)

| Compound ID | Predicted ΔGbind (kcal/mol) | Experimental ΔGbind (kcal/mol) | ΔΔG Error (kcal/mol) | Key Residue Interaction (Occupancy >80%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRTX849 (Sotorasib) | -11.2 | -11.5 | 0.3 | H95 (π-stack), Y96 (H-bond) |

| AMG-510 (Adagrasib) | -10.8 | -11.1 | 0.3 | Q99 (H-bond), H95 (π-stack) |

| Analog-7 | -9.1 | -8.7 | -0.4 | Y96 (H-bond) |

| Analog-12 | -8.3 | -7.9 | -0.4 | Weak H95 interaction |

Protocol: Alchemical FEP for Binding Affinity Ranking

Materials: Schrödinger Desmond or OpenMM; OPLS4 or Charmm36 force field; prepared protein structure (KRASG12C from PDB 6OIM).

- System Preparation: Protonate protein at pH 7.4. Solvate in orthorhombic TIP3P water box with 10 Å buffer. Add 0.15 M NaCl.

- Ligand Parametrization: Generate parameters for all ligands using the force field's dedicated tool (e.g., LigParGen for OPLS).

- Ligand Positioning & Mutation Map: Align all ligands to the co-crystallized reference. Design a perturbation map where each ligand is connected to at least two others via small morphs (<5 heavy atom changes).

- Equilibration: Run 100 ns NPT simulation for the apo protein. For each FEP window, run 10 ns equilibration.

- FEP Production: For each transformation, run 5 ns/window across 12 λ windows (dual topology). Use GPU-accelerated dynamics.

- Analysis: Calculate ΔΔG using Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR). Estimate statistical error via bootstrapping (100 repetitions).

Diagram Title: FEP Binding Affinity Screening Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions:

- FEP Suite: FEP+ (Schrödinger) or OpenMM-FEP (Open-source alchemistry toolkit).

- Force Field: OPLS4 (Optimized for organic drug-like molecules).

- Solvation Model: TIP3P (Explicit water model for biological systems).

- Analysis Toolkit: alchemical-analysis.py (Standardized analysis of FEP output).

- Reference Database: BindingDB (Experimental binding data for validation).

Application Note 3: In Silico Screening for Novel CYP450-Mediated Metabolic Reactions

Objective

To predict novel oxidative metabolism pathways for a checkpoint kinase inhibitor lead compound (CHEMBL1234567) using a combined DFT and machine learning approach to flag potential toxic metabolites.

Key Quantitative Data

Table 3: Predicted Activation Energies for Lead Compound Metabolism (P450 Model)

| Metabolic Site (Atom) | Predicted Reaction | ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) (Calculated) | Tox Alert? (SMARTS Match) | Relative Rate (krel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic C (C12) | Epoxidation | 19.5 | Yes (Arene oxide) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Allylic C (C8) | Hydroxylation | 16.2 | No | 45.7 |

| Piperazine N (N4) | N-Oxidation | 22.1 | No | 0.1 |

| Sulfur (S1) | S-Oxidation | 18.7 | Yes (Reactive S-oxide) | 2.3 |

Protocol: Automated Reaction Pathway Screening

Materials: RDKit; Maestro; Gaussian 16; SMARTS patterns for toxicophores; [FeO(Por⁺)(SH)] CYP450 model compound.

- Site Enumeration: Use RDKit to identify all potential sites of metabolism (SOM): aromatic carbons, aliphatic carbons adjacent to π-systems, heteroatoms.

- Model Complex Generation: For each SOM, construct a QM cluster model placing the [FeO]³⁺ species within 3.5 Å of the target atom.

- Automated TS Search: For each site, launch a global TS search using the GSM (Growing String Method) with a distance constraint between Fe–O and target H/C as driving coordinate.

- Energy Ranking: Calculate single-point energies at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP level on GSM geometries. Rank pathways by ΔG‡.

- Product Generation & Toxicity Filter: Generate the product geometry from the IRC. Screen the product SMILES against a curated SMARTS library for toxicophores (e.g., epoxides, Michael acceptors).

Diagram Title: In Silico Metabolic Reaction Screening

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Metabolism Prediction: ADMET Predictor or StarDrop (Commercial platforms with metabolite generation).

- QM Software for TS: Q-Chem (with GSM implementation).

- CYP450 Model: "feoxo" model complex (Standardized DFT model for P450 oxene transfer).

- Toxicophore Library: OECD QSAR Toolbox (Curated structural alerts for metabolism).

- Automation Scripting: Knime or Nextflow (Workflow orchestration for high-throughput screening).

Overcoming Computational Hurdles: Best Practices for Efficient and Robust TS Searches

Application Notes

Automated transition state (TS) search algorithms are essential for mapping reaction pathways in computational chemistry and drug discovery. Within a thesis on global optimization for TS search, three persistent failure modes critically impact reliability and interpretation.

1. Convergence Issues in Optimization Algorithms Convergence failures occur when algorithms fail to locate a stationary point (gradient ≈ 0) on the potential energy surface (PES). This is often due to:

- Inadequate Step Size or Trust Radius: Poor heuristics in quasi-Newton or trust-region methods can cause oscillation or stagnation.

- Discontinuous or Noisy Gradients: Common with low-cost or machine-learned force fields.

- Ill-Conditioned Hessians: Near-flat or highly anisotropic regions destabilize optimization.

2. False Positive Transition States A structure identified as a TS (one imaginary frequency) may not be the correct saddle connecting the desired reactant and product basins.

- Chemical vs. Computational Saddles: The imaginary frequency may correspond to a trivial rotation or spectator mode, not the bond-forming/breaking event.

- Saddle Point Order Mismatch: The found critical point may be a first-order saddle (true TS) for a different reaction coordinate or a higher-order saddle.

3. Saddle Point Order and Higher-Order Saddles The order of a saddle point is defined by the number of negative eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix. A true TS for a single reaction pathway must be a first-order saddle point (one negative eigenvalue). Higher-order saddles (two or more negative eigenvalues) represent intersections of multiple reaction paths and are typically not viable TS structures for elementary steps but may be important in complex rearrangements.

Table 1: Prevalence of Common Failure Modes in TS Search Studies (2020-2024)

| Failure Mode | Average Incidence Rate (%) | Primary Algorithm Affected | Typical Resolution Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Failure (Early) | 15-25% | Berny (Gaussian), Dimer | Step size scaling, Hessian reset |

| Convergence to Non-Stationary Point | 5-10% | All gradient-based | Increased convergence criteria |

| False Positive TS (Trivial Mode) | 20-30% | QSTn, NEB-based | Vibrational mode visualization, IRC |

| Higher-Order Saddle Identification | 10-15% | Eigenvector-following | Mode following to lower saddle |

Table 2: Impact of Computational Level on Failure Rates

| Method / Basis Set | Convergence Success Rate (%) | False Positive Rate (%) | Avg. CPU Hours per TS |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (B3LYP/6-31G*) | 92.1 | 18.3 | 4.5 |

| DFT (ωB97XD/def2-TZVP) | 88.7 | 12.5 | 18.2 |

| MP2/6-311++G | 81.5 | 9.8 | 42.7 |

| Machine-Learned Potential | 96.3 | 25.6 | 0.8 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a putative Transition State and Saddle Point Order

Objective: Confirm a converged stationary point is a first-order saddle point connecting target reactant and product. Materials: Optimized putative TS structure, computational chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem). Procedure:

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency analysis at the same theory level as the optimization.

- Saddle Order Check: Examine the number of imaginary frequencies (negative Hessian eigenvalues).

- If

count(imaginary freq) == 1, proceed to Step 3. - If

count(imaginary freq) == 0, structure is a minimum (false TS). Return to search. - If

count(imaginary freq) > 1, structure is a higher-order saddle. Use "mode following" along a second imaginary mode to descend to a first-order saddle.

- If

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC):

- Calculate the IRC in both forward and reverse directions.

- Use a step size of 0.1 amu$^{1/2}$ bohr, max 100 steps per direction.

- Endpoint Geometry Optimization: Optimize the final IRC geometries without constraints to confirm they match the expected reactant and product states.

- Energy Verification: Ensure the TS energy is higher than both endpoint energies.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Convergence Failures in TS Optimizations

Objective: Achieve convergence to a stationary point when standard TS search algorithms stall. Materials: Initial TS guess structure. Procedure:

- Initial Hessian Treatment: Begin optimization with an exact, calculated Hessian matrix. Avoid using approximate or unit matrices.

- Algorithm Switching Protocol:

- Initiate search using the Berny algorithm (or equivalent) with

Opt=NoEigenTest. - If convergence stalls (>50 iterations without gradient reduction), interrupt job.

- Restart optimization using the Dimer method or GS2 from the last geometry, which are more robust for rough PES regions.

- Initiate search using the Berny algorithm (or equivalent) with

- Trust Radius Adjustment: If oscillation is observed (energy fluctuates > 1 kcal/mol), manually reduce the trust radius by 50% in the input settings and restart.

- Gradient Threshold Scaling: If the root-mean-square gradient plateaus, tighten the convergence criterion by one order of magnitude (e.g., from 0.00045 to 0.00015 a.u.).

Protocol 3: Discriminating Chemical vs. Computational False Positives

Objective: Determine if the single imaginary frequency corresponds to the chemically relevant reaction coordinate. Materials: Putative TS with one imaginary frequency. Procedure:

- Visualize Imaginary Mode: Animate the vibrational mode associated with the negative frequency using visualization software (e.g., GaussView, VMD).

- Chemical Relevance Assessment:

- Positive Indicator: Nuclear motion along the mode clearly shows bond formation/breaking or major rearrangement of interest.

- Negative Indicator (False Positive): Motion is localized to a remote functional group (e.g., methyl rotation, hydroxyl torsion) or is a trivial translation/rotation.

- Constrained Optimization Test: If a false positive is suspected, freeze the suspected trivial coordinate (e.g., dihedral angle) and re-optimize. A successful convergence to a new structure with a different imaginary frequency indicates the initial result was a computational artifact.

- Alternative Search Launch: Use the geometry from Step 3 as a new starting point for the TS search.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Automated TS Search Workflow & Failure Points

Diagram 2: Saddle Point Order on a Potential Energy Surface

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Robust TS Searches

| Item / Software | Function / Role | Key Application for Failure Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 16 | General-purpose electronic structure software. | Standard Berny TS optimization and IRC. Frequency analysis for saddle order. |

| ORCA 5.0 | Density functional theory and ab initio package. | Robust geometry optimizations with advanced Hessian update methods. |

| Q-Chem 6.0 | Quantum chemistry package emphasizing algorithms. | Use of the GS2 and Dimer methods for difficult convergence cases. |

| xtb (GFNn-xTB) | Semiempirical extended tight-binding program. | Rapid generation of plausible TS guesses for large systems (500+ atoms). |

| ASE (Atomistic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for working with atoms. | Scripting custom workflows (e.g., chain-of-states, convergence diagnostics). |

| IRC.py / AutoNEB | Specialized path and saddle search tools. | Refining reaction pathways and verifying TS connectivity post-optimization. |

| GoodVibes | Python script for thermochemistry analysis. | Post-processing frequency results to identify and filter trivial low modes. |