Atomistic vs. Coarse-Grained Models: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Simulation

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of atomistic and coarse-grained potential models for researchers and professionals in computational biology and drug development.

Atomistic vs. Coarse-Grained Models: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of atomistic and coarse-grained potential models for researchers and professionals in computational biology and drug development. It explores the foundational principles behind these simulation approaches, contrasting their inherent trade-offs between resolution and scale. The content delves into advanced methodological developments, particularly the integration of machine learning to bridge the resolution gap, and addresses key challenges in model parameterization and optimization. Finally, it outlines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses, offering strategic insights for selecting the appropriate model to study complex biological processes, from protein folding to membrane interactions, thereby accelerating biomedical research.

Understanding the Multiscale Challenge: Atomistic Detail vs. Coarse-Grained Scale

In the pursuit of understanding molecular interactions for drug development and materials science, computational scientists operate across a vast spectrum of simulation resolutions. This spectrum ranges from highly detailed quantum mechanical (QM) calculations, which model electron behavior, to all-atom (AA) molecular dynamics (MD), which simulates every atom using classical force fields, and further to coarse-grained (CG) MD methods, where groups of atoms are merged into single interaction sites or "beads" to access larger temporal and spatial scales [1] [2]. The choice of model is invariably a trade-off between computational cost and resolution, impacting the phenomena that can be studied. AA MD provides high resolution and is adept at capturing detailed interfacial interactions but becomes computationally prohibitive for large systems or long time scales [2]. CGMD addresses this limitation by simplifying molecular structures, enabling the study of complex molecular phenomena—from self-assembly to protein folding—over microseconds and micrometers, scales often inaccessible to AAMD [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, detailing their performance, underlying protocols, and practical applications in modern research.

Method Comparison: Performance and Precision

Computational Efficiency and Application Scope

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Simulation Methods Across Key Metrics

| Metric | Quantum Mechanics (QM) | All-Atom MD (AA) | Coarse-Grained MD (CG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Scale | Atomic/Sub-Atomic (Å) | Nanometers (nm) | Micrometers (µm) |

| Temporal Scale | Femtoseconds (fs) | Picoseconds to Nanoseconds (ps-ns) | Microseconds to Milliseconds (µs-ms) |

| Typical System Size | 10s - 1000s of atoms | 1000s - millions of atoms | 1000s of beads (representing 10,000s+ atoms) |

| Key Applications | Electronic properties, reaction mechanisms, force field parametrization [1] | Detailed ligand-protein binding, specific molecular interactions | Membrane dynamics, polymer self-assembly, large protein complexes [2] |

| Representative Software/Tools | Gaussian, ORCA, VASP | GROMACS [2], AMBER, LAMMPS [2] | MARTINI [1] [2], VOTCA [2], MagiC [2], Martini3 [2] |

Quantitative Performance in Practical Applications

The performance differential between simulation methods has been quantitatively assessed in various domains, from drug discovery to material property prediction.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Various Modeling Approaches

| Application Domain | Compared Methods | Performance Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proof-of-Concept (POC) Trials [3] | Pharmacometric Model vs. Conventional t-test | 4.3 to 8.4-fold reduction in sample size to achieve 80% power | Parallel design with placebo and active dose arms; Stroke & Diabetes examples |

| Dose-Ranging POC Trials [3] | Pharmacometric Model vs. Conventional t-test | 4.3 to 14-fold reduction in total study size | Scenarios with multiple active doses and placebo |

| Drug Target Prediction [4] | Deep Learning vs. Other ML Methods (SVM, KNN, RF) | Deep Learning significantly outperformed all competing methods | Large-scale benchmark of 1300 assays and ~500,000 compounds |

| Population PK Modeling [5] | AI/ML Models (incl. Neural ODE) vs. NONMEM (NLME) | AI/ML models often outperformed NONMEM in predictive performance (RMSE, MAE, R²) | Analysis of simulated and real clinical data from 1,770 patients |

| Coarse-Grained Force Field Accuracy [1] | CG Models (e.g., MARTINI, ECRW) vs. AA Models vs. Experiment | CG models show varying accuracy in density, diffusion, and conductivity vs. experiment and AA | Comparison for [C4mim][BF4] ionic liquid |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Bottom-Up Coarse-Grained Model Development

A common and rigorous approach for developing accurate CG models is the bottom-up methodology, which derives parameters from reference all-atom data [1]. The general workflow is as follows:

- System Selection and AA Simulation: A representative system is simulated using a validated all-atom force field to generate a high-quality reference trajectory. This trajectory includes atomic positions and, crucially, forces [6].

- CG Mapping Definition: A mapping scheme is defined, specifying how groups of atoms are combined into a single CG bead. Common schemes are based on chemical intuition or systematic methods like relative entropy minimization [1].

- Force Field Parameterization: The CG force field parameters are optimized to reproduce the behavior of the AA system. This is the core step and can be achieved through several methods:

- Force Matching (Variational Coarse-Graining): A CG force field is learned by minimizing the mean-squared error between the forces predicted by the CG model and the reference forces from the AA simulation projected onto the CG coordinates [6].

- Inverse Boltzmann Inversion (IBI): The non-bonded potentials are iteratively refined until the radial distribution functions (RDFs) of the CG model match those from the AA reference [1].

- Relative Entropy Minimization: This approach minimizes the relative entropy, or informational divergence, between the probability distributions of the AA and CG systems [2].

- Model Validation: The optimized CG model is used to simulate the system, and its predictions for key properties (e.g., density, radius of gyration, diffusion constants) are compared against the original AA simulations or experimental data to assess its accuracy and transferability [2].

Protocol for Rigorous Machine Learning Method Comparison in Drug Discovery

To ensure fair and realistic comparison of ML models in drug discovery, specific protocols have been developed to avoid common biases [4]:

- Benchmark Dataset Curation: A large and diverse dataset, such as the one extracted from ChEMBL containing ~500,000 compounds and over 1,000 assays, is used to ensure generalizable conclusions [4].

- Cluster-Cross-Validation: Instead of random splits, whole clusters of chemically similar compounds (based on scaffolds) are assigned to training or test sets. This prevents over-optimism by ensuring the model predicts activities for entirely new chemical series, reflecting the real-world discovery process [4].

- Nested Cross-Validation for Hyperparameter Tuning: An outer loop estimates the model's performance, while an inner loop is used exclusively for hyperparameter optimization. This strict separation prevents information from the test set from leaking into the model building process (hyperparameter selection bias) [4].

- Performance Evaluation: Models are evaluated using robust metrics (e.g., AUC, RMSE, R²) on the held-out test clusters, providing a realistic estimate of their predictive power in practice [5] [4].

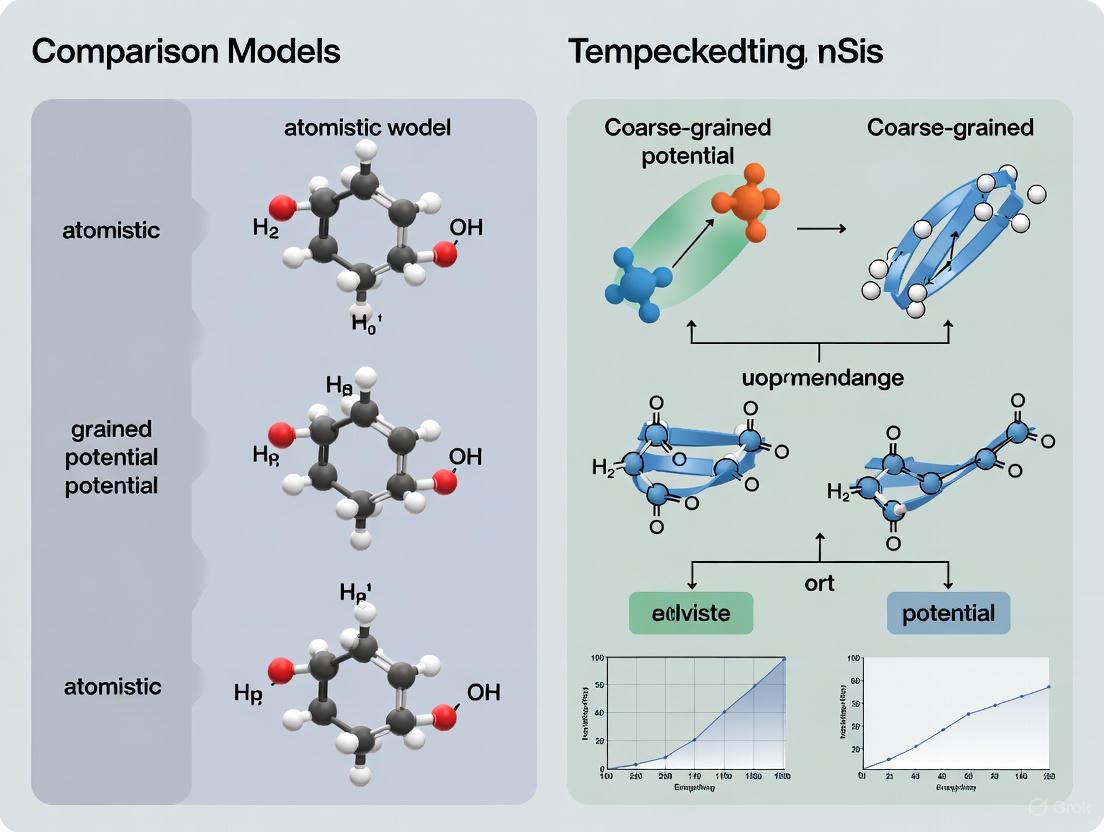

Diagram 1: Bottom-up coarse-graining workflow for molecular simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Molecular Simulation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [2] | Software Engine | High-performance MD package for running both AA and CG simulations. |

| LAMMPS [2] | Software Engine | A versatile MD simulator with extensive support for CG and reactive force fields. |

| MARTINI [1] [2] | Coarse-Grained Force Field | A widely used top-down CG force field, particularly for biomolecular and material systems. |

| VOTCA [2] | Software Toolkit | A suite of tools for bottom-up coarse-graining, implementing methods like IBI and force matching. |

| NONMEM [5] | Software Platform | The gold-standard software for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in population pharmacokinetics. |

| Neural ODEs [5] | Modeling Technique | A deep learning architecture that models continuous-time dynamics, showing strong performance in PK modeling. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [2] | Optimization Algorithm | An efficient method for optimizing CG force field parameters, balancing exploration and exploitation with fewer evaluations. |

The landscape of molecular simulation offers a powerful continuum of methods, each with distinct strengths. Quantum mechanics provides the fundamental foundation but is limited in scale. All-atom molecular dynamics offers a balance of detail and practicality for many systems. Coarse-grained models, particularly when enhanced by machine learning and robust parameterization protocols, dramatically extend the accessible scales, enabling the study of mesoscopic phenomena critical in drug development and material science [2] [1]. Quantitative comparisons consistently show that advanced model-based approaches—whether in clinical trial analysis, target prediction, or force field development—can yield substantial efficiency gains, often reducing required resources by an order of magnitude [3] [4]. The choice of method must be guided by the specific research question, balancing the need for atomic detail with the practical constraints of computational cost and the scale of the biological or chemical process under investigation.

In molecular simulations, the all-atom (AA) model represents the highest standard of resolution, explicitly modeling every atom within a system, including hydrogen atoms. This stands in contrast to united-atom (UA) representations, which simplify aliphatic groups by representing carbon and hydrogen atoms as single, merged interaction sites [7], and coarse-grained (CG) models, which group multiple atoms into even larger "beads" to dramatically reduce computational cost [8]. The choice of model resolution represents a fundamental trade-off between computational expense and physical detail. AA models are indispensable for investigating phenomena where atomic-level interactions are critical, such as precise molecular recognition, enzyme catalysis, and drug binding [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the AA model's performance against alternative representations, focusing on experimental data and its established role within the broader context of atomistic versus coarse-grained potential model research.

Unmatched Resolution: The Key Strengths of the All-Atom Model

Explicit Representation of Atomic Interactions

The primary advantage of the AA model is its complete physical representation. By explicitly including every hydrogen atom, AA models can directly describe specific intermolecular interactions, most notably hydrogen bonding and other highly directional forces, which are critical for the structural integrity and function of biomolecules [7]. This level of detail is essential for accurately simulating biological processes where these fine-grained interactions determine mechanistic pathways. For instance, the explicit treatment of hydrogen atoms allows for a more realistic depiction of solvation dynamics and the dielectric properties of the environment [7].

Target Properties and Performance in Force Field Comparisons

The accuracy of a force field is intrinsically linked to its resolution. A dedicated 2022 study performed a direct comparison between UA and AA resolutions for a force field applied to saturated acyclic (halo)alkanes. The parameters for both force-field versions were optimized in an automated way (CombiFF) against a large set of experimental data, ensuring a fair comparison [7]. The table below summarizes the performance of the AA and UA representations for a range of physical properties after optimization.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AA and UA Representations for Various Physical Properties

| Property | AA Performance | UA Performance | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Density (ρliq) | Very Accurate | Very Accurate | Target property; similar accuracy after optimization [7]. |

| Vaporization Enthalpy (ΔHvap) | Very Accurate | Very Accurate | Target property; similar accuracy after optimization [7]. |

| Shear Viscosity (η) | More Accurate | Less Accurate | AA representation yielded superior results [7]. |

| Surface Tension (γ) | Comparably Accurate | Comparably Accurate | Both resolutions achieved similar accuracy [7]. |

| Hydration Free Energy (ΔGwat) | Less Accurate | More Accurate | UA representation yielded superior results in this case [7]. |

| Self-Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Comparably Accurate | Comparably Accurate | Both resolutions achieved similar accuracy [7]. |

Generating Atomic-Resolution Conformational Ensembles

AA models are paramount for determining atomic-resolution conformational ensembles, especially for highly flexible systems like intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with modern AA force fields can generate atomically detailed structural descriptions of the rapidly interconverting states populated by IDPs in solution [9]. The accuracy of these ensembles has been significantly improved through integrative approaches that combine AA-MD simulations with experimental data from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) using maximum entropy reweighting procedures [9]. This allows researchers to achieve a "force-field independent approximation" of the true solution ensemble, a feat that is only possible starting from atomic-level detail [9].

Inherent Limitations: The Computational Cost of Detail

The Fundamental Bottleneck: System Size and Timescales

The most significant limitation of AA simulations is their prohibitive computational cost. Explicitly simulating every atom, including hydrogens, results in a much larger number of particles and interaction sites compared to UA or CG models. This directly limits the accessible time and length scales of the simulation [8]. Biological processes such as protein folding, large-scale conformational changes, and protein-protein interactions often occur on microsecond to second timescales and involve large molecular complexes—realms that are often beyond the practical reach of routine AA simulations [10].

The Multiscale Solution: Integrating AA with Coarser Models

To overcome the limitations of AA models while retaining their strengths, researchers have developed multiscale modeling workflows. These strategies leverage the strengths of different resolutions: CG models are used to sample large-scale conformational changes and long-timescale dynamics, while AA models are applied to specific regions of interest for atomic-detail analysis [10]. A key technological advancement enabling these workflows is backmapping—the process of reconstructing an AA representation from a lower-resolution (e.g., CG or side-chain-based) model [11] [8] [10]. Modern methods employ machine learning, such as diffusion models, to learn the mapping between scales and recover detailed structures from coarse representations [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AA and Multiscale Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Type/Function | Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CombiFF | Automated parameterization approach | Enables systematic optimization and comparison of force-field parameters for different resolutions (e.g., UA vs. AA) [7]. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting | Computational algorithm | Integrates AA-MD simulations with sparse experimental data (NMR, SAXS) to determine accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs [9]. |

| Backmapping Tools | Software/Algorithm | Reconstructs all-atom structures from coarse-grained representations; essential for multiscale workflows [11] [10]. |

| MuMMI/UCG-mini-MuMMI | Multiscale simulation workflow | Integrates ultra-coarse-grained (UCG), CG, and AA models to study large biological systems (e.g., RAS-RAF interactions) at reduced computational cost [10]. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Validation and Comparison

Protocol 1: Direct Force-Field Comparison Using CombiFF

This protocol outlines the methodology for a fair comparison between AA and UA force-field representations, as performed in a 2022 study [7].

- System Selection: Define a specific family of molecules (e.g., saturated acyclic (halo)alkanes).

- Parameter Optimization: Use an automated procedure (CombiFF) to refine the force-field parameters for both the AA and UA representations against the same set of experimental target data (e.g., pure-liquid densities ρliq and vaporization enthalpies ΔHvap).

- Target Property Calculation: Run MD simulations with the optimized parameters to calculate the target properties.

- Validation on Secondary Properties: Extend the comparison to properties not included in the parameterization targets (e.g., shear viscosity η, hydration free energy ΔGwat, self-diffusion coefficient D).

- Accuracy Assessment: Quantify the accuracy of each representation by comparing simulation results against experimental data for all properties.

Protocol 2: Determining Accurate IDP Ensembles via Maximum Entropy Reweighting

This protocol describes an integrative method for generating force-field independent, atomic-resolution ensembles of IDPs, as detailed in a 2025 study [9].

- Initial AA-MD Simulation: Perform long-timescale all-atom MD simulations of the IDP using different state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm36m).

- Experimental Data Collection: Gather extensive experimental data for the IDP, such as NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, and SAXS profiles.

- Calculate Observables: Use forward models to predict the experimental observables from every snapshot (conformation) of the unbiased MD ensemble.

- Automated Reweighting: Apply a maximum entropy reweighting procedure. This algorithm assigns new statistical weights to each snapshot in the ensemble with the constraint that the reweighted ensemble's averaged observables match the experimental data. A single parameter (the desired effective ensemble size) automatically balances the restraints from different experimental datasets.

- Ensemble Validation: Assess the similarity and robustness of the reweighted ensembles derived from different initial force fields to approach a "force-field independent" solution ensemble.

The following diagram illustrates this integrative workflow.

The all-atom model remains the gold standard for molecular simulation when atomic-level detail is non-negotiable. Its ability to explicitly capture fine-grained interactions makes it indispensable for studying specific biological mechanisms and for generating reference data. However, its severe computational constraints naturally integrate it into a larger multiscale ecosystem. The future of simulating complex biological systems does not lie in choosing one model over another, but in strategically leveraging AA, UA, and CG resolutions within unified workflows. The continued development of robust parameterization tools, accurate backmapping techniques, and integrative validation methods is crucial to seamlessly bridge these scales, maximizing physical insight while managing computational resources.

Biomolecular simulations are an indispensable tool for advancing our understanding of complex biological dynamics, with critical applications ranging from drug discovery to the molecular characterization of virus-host interactions [8]. However, biological processes are inherently multiscale, involving intricate interactions across a vast range of length and time scales that present a fundamental challenge for computational methods [8]. All-atom (AA) molecular dynamics simulations, while providing unparalleled detail at atomistic resolution, remain severely limited by computational constraints, typically capturing only short timescales and small conformational changes [8] [12]. In contrast, coarse-grained (CG) models address this limitation by systematically reducing molecular complexity, thereby extending simulations to biologically relevant time and length scales by orders of magnitude [13] [12]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CG models against traditional atomistic approaches, examining their theoretical foundations, performance metrics, and practical applications in biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundations: The Physical Basis of Coarse-Graining

The fundamental principle underlying coarse-grained modeling is a reduction in the number of degrees of freedom in a molecular system. CG models achieve this by grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites, or "pseudo-atoms," thereby creating a simplified representation that retains essential molecular features while eliminating unnecessary atomic details [13] [14]. The motion of these coarse-grained sites is governed by the potential of mean force, which represents the free energy surface obtained by integrating out the secondary degrees of freedom [13].

From a statistical mechanics perspective, the equations of motion for CG degrees of freedom can be derived using the Mori-Zwanzig projection-operator formalism, which reveals that the net motion is governed by three primary components: the mean forces (averaged over the atoms constituting the interaction sites), friction forces (depending on time correlation of force fluctuations), and stochastic forces [13]. In practical implementations, the friction and stochastic force terms are typically incorporated through Langevin dynamics, which assumes that fine-grained degrees of freedom move much faster than coarse-grained ones [13]. This theoretical foundation justifies the use of simplified dynamics that enable the dramatic acceleration of simulations compared to all-atom approaches.

Table: Fundamental Components of Coarse-Grained Dynamics

| Force Component | Physical Origin | Mathematical Representation | Practical Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Force | Potential of mean force from integrated degrees of freedom | -∇ᵢW(R) where W(R) is the potential of mean force | Directly computed from CG force field |

| Friction Force | Energy dissipation from fast variables | -Γq̇ where Γ is friction coefficient | Langevin dynamics thermostat |

| Stochastic Force | Random collisions with integrated degrees of freedom | fᵣₐₙ₈ with ⟨fᵣₐₙ₈(t)fᵣₐₙ₈(t')⟩ = 2kBTΓδ(t-t') | Random forces in Langevin dynamics |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis of Simulation Approaches

Computational Efficiency and Accessible Timescales

The primary advantage of CG models is their dramatic acceleration of simulation timescales compared to all-atom methods. While all-atom molecular dynamics is typically limited to microsecond timescales for even moderately sized systems, CG models can access millisecond to second timescales, encompassing biologically critical processes like protein folding, large-scale conformational changes, and molecular assembly [12] [15]. This performance improvement stems from multiple factors: the reduction in degrees of freedom smooths high-frequency atomic vibrations and flattens the free-energy landscape, reducing molecular friction and enabling faster exploration of configuration space [1]. Additionally, the elimination of fastest vibrations permits the use of significantly larger integration time steps (typically 10-20 femtoseconds for CG models versus 1-2 femtoseconds for AA models) [1].

Recent advances in machine learning-accelerated CG models have demonstrated particularly impressive performance gains. The CGSchNet model, for instance, has been shown to be several orders of magnitude faster than equivalent all-atom molecular dynamics while maintaining comparable accuracy for predicting protein folding pathways and metastable states [15]. Similarly, commercial implementations under development aim to achieve speedups of 500 times compared to GPU-based classical molecular dynamics simulators [16].

Table: Performance Comparison of Biomolecular Simulation Methods

| Parameter | All-Atom MD | Traditional CG Models | ML-Accelerated CG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Step | 1-2 fs [1] | 10-20 fs [1] | 10-20 fs+ |

| Typical Timescale | Nanoseconds to microseconds [12] | Microseconds to milliseconds [12] | Milliseconds to seconds [15] |

| System Size Limit | ~10⁶ atoms [12] | ~10⁸ atoms | ~10⁸ atoms |

| Relative Speed | 1x | 10³-10⁴x [15] | 10⁴-10⁶x [15] [16] |

| Accuracy for Folding | Quantitative with modern force fields [15] | Qualitative to semi-quantitative [15] | Near quantitative for certain systems [15] |

| Transferability | High across diverse systems | System-specific limitations [15] | Improving with neural network approaches [15] |

Accuracy and Predictive Capability

While CG models offer dramatic speed improvements, their accuracy must be carefully evaluated against all-atom simulations and experimental data. Traditional CG models often sacrifice atomic-level detail, making the parameterization of reliable and transferable potentials a persistent challenge [8]. The MARTINI force field, for example, effectively models intermolecular interactions including membrane structure formation and protein interactions, but inaccurately represents intramolecular protein dynamics [15]. Similarly, structure-based models like UNRES or AWSEM often fail to capture alternative metastable states beyond the native fold [15].

Recent machine learning approaches have substantially improved CG model accuracy. The CGSchNet model demonstrates that transferable bottom-up CG force fields can successfully predict metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures, fluctuations of intrinsically disordered proteins, and relative folding free energies of protein mutants [15]. Quantitative comparisons show that for small fast-folding proteins like chignolin, TRPcage, and villin headpiece, ML-CG models can reproduce free energy landscapes with folded states having fraction of native contacts (Q) close to 1 and low Cα root-mean-square deviation values [15]. However, challenges remain for more complex systems like the beta-beta-alpha fold (BBA) which contains both helical and anti-parallel β-sheet motifs [15].

Methodological Approaches: Force Field Development and Parameterization

Coarse-Grained Force Field Paradigms

The development of accurate CG force fields remains the most significant challenge in coarse-grained modeling [13]. Two primary philosophical approaches dominate the field: top-down and bottom-up parameterization strategies. Top-down methods parameterize CG models directly against experimental macroscopic properties, while bottom-up approaches use statistical mechanics principles to preserve microscopic properties of atomistic models [1]. Bottom-up methods include several specialized techniques:

- Inverse Boltzmann Inversion (IBI): Iteratively adjusts potentials to match target radial distribution functions [1]

- Multiscale Coarse-Graining (MS-CG): Uses force-matching to optimize CG potentials against atomistic force data [1]

- Relative Entropy Minimization: Minimizes the relative entropy between CG and AA distributions [1]

- Extended Conditional Reversible Work (ECRW): Determines potentials based on reversible work calculations [1]

The energy function for CG models typically includes both bonded and nonbonded terms, with the analytical functional form often copied from all-atom force fields [13]. However, this approach can result in insufficient capacity to model complex systems like protein structures, as the fine-grained degrees of freedom can create strong coupling between CG degrees of freedom [13].

Specialized CG Models for Biological Applications

Different biomolecular systems often require specialized CG approaches optimized for their specific physical properties:

Protein-Specific Models: The HPS-Urry model uses a hydropathy scale derived from inverse temperature transitions in elastin-like polypeptides to simulate sequence-specific behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and their liquid-liquid phase separation [17]. This model successfully predicts reduced phase separation propensity upon mutations (R-to-K and Y-to-F) that earlier models failed to capture [17].

Membrane Models: The MARTINI force field provides optimized parameters for lipid bilayers and membrane proteins, enabling studies of membrane remodeling, protein insertion, and lipid-protein interactions [12].

Nucleic Acid Models: Specialized CG models for DNA and RNA, such as SimRNA, enable the simulation of nucleic acid folding, protein-nucleic acid interactions, and large-scale conformational changes in nucleoprotein complexes [12] [14].

Table: Comparison of Popular Coarse-Grained Force Fields

| Force Field | CG Mapping | Parameterization | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARTINI | ~4 heavy atoms per bead [1] | Top-down & bottom-up hybrid | Excellent for membranes & intermolecular interactions [15] | Poor intramolecular protein dynamics [15] |

| UNRES | 2 backbone sites per residue [15] | Physics-based & statistical | Effective for protein folding [15] | Limited to specific protein types [15] |

| AWSEM | 3 backbone sites per residue [15] | Knowledge-based | Good for structure prediction [15] | Misses alternative metastable states [15] |

| HPS-Urry | 1 bead per amino acid [17] | Hydropathy scale based | Excellent for IDPs & phase separation [17] | Less accurate for folded proteins [17] |

| CGSchNet | Cα-based mapping [15] | ML bottom-up force matching | Transferable, high accuracy [15] | Computationally intensive training [15] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for CG Model Validation

Free Energy Landscape Calculation

A critical validation methodology for CG models involves comparing free energy landscapes against all-atom references or experimental data. The standard protocol involves:

Equilibrium Sampling: Running extensive molecular dynamics simulations using the CG force field, often enhanced with advanced sampling techniques like parallel tempering (replica exchange) to ensure proper convergence [15].

Collective Variable Selection: Identifying appropriate order parameters that describe the essential dynamics of the system, typically including:

- Fraction of native contacts (Q) - measures structural similarity to native state

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) - quantifies structural deviation

- Radius of gyration (Rg) - characterizes chain compactness [15]

Probability Distribution Construction: Calculating the probability distribution P(Q,RMSD) from simulation trajectories and converting to free energy via F(Q,RMSD) = -kBT ln P(Q,RMSD) [15].

Metastable State Identification: Locating local minima on the free energy surface that correspond to functionally relevant states (folded, unfolded, intermediate, misfolded) [15].

This approach was used to validate the CGSchNet model against all-atom references for multiple fast-folding proteins, demonstrating its ability to correctly predict metastable folding and unfolding transitions [15].

Transferability Testing Across Sequence Space

A rigorous test for CG models involves evaluating their performance on proteins not included in the training set. The established protocol includes:

Training Set Curation: Assembling a diverse set of protein sequences and structures with varied folds and sequence properties for force field parameterization [15].

Sequence Similarity Filtering: Ensuring test proteins have low sequence similarity (<40%) to any training set sequences to prevent overfitting [15].

Folding from Extended States: Initializing simulations from extended conformations rather than native structures to test true predictive capability [15].

Multiple Metric Validation: Comparing simulations against experimental or all-atom reference data using various structural metrics:

- Average RMSD to native structure

- Root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of Cα atoms

- Native contact preservation

- Comparison with experimental scattering data or NMR measurements [15]

This methodology revealed that the CGSchNet model could successfully fold proteins like the 54-residue engrailed homeodomain (1ENH) and 73-residue de novo designed protein alpha3D (2A3D) that were not used in training [15].

Table: Key Computational Tools for Coarse-Grained Biomolecular Simulation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | MD Software | Large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator | General purpose MD, various CG models [14] |

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics package | All-atom and CG simulations with extensive analysis [12] |

| MARTINI | Force Field | Generic coarse-grained force field | Membranes, proteins, carbohydrates [12] [14] |

| PLUMED | Plugin | Enhanced sampling and free energy calculations | Metadynamics, umbrella sampling for CG models [15] |

| VMD | Visualization | Molecular visualization and analysis | Trajectory analysis for CG simulations [12] |

| CGSchNet | ML Force Field | Neural network-based transferable CG model | Protein folding and dynamics [15] |

| HPS-Urry | Specialized FF | IDP and phase separation simulations | Intrinsically disordered proteins [17] |

| ESPResSo | MD Software | Extensible Simulation Package for Soft Matter | Advanced electrostatics and coarse-graining [14] |

Coarse-grained models have firmly established their value as essential tools for accessing biological timescales inaccessible to all-atom molecular dynamics. The continuing evolution of CG methodologies, particularly through integration with machine learning approaches, promises to further bridge the accuracy gap while maintaining computational efficiency. The development of truly transferable bottom-up force fields that retain chemical specificity while enabling millisecond-scale simulations represents the current frontier in the field [15]. As these methods mature, they will increasingly enable the simulation of complex cellular processes at near-atomic detail, providing unprecedented insights into biological mechanisms and accelerating therapeutic discovery across a broad spectrum of diseases [16].

In the field of biomolecular simulation, researchers face a fundamental trade-off: the choice between high-resolution models that capture atomic detail and computationally efficient models that access biologically relevant timescales. All-atom (AA) molecular dynamics simulations provide unparalleled detail but are computationally intensive, typically limited to short timescales and small systems. In contrast, coarse-grained (CG) models reduce molecular complexity to extend simulations to longer timescales and larger systems, though at the cost of atomic-level accuracy [8]. This guide objectively compares these approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies to help researchers select appropriate models for specific scientific inquiries.

Quantitative Comparison of Simulation Approaches

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Atomistic vs. Coarse-Grained Models

| Characteristic | All-Atom (AA) Models | Coarse-Grained (CG) Models |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Atomic-level (individual atoms) | Residue/bead level (10+ heavy atoms per particle) [18] |

| Timescale Accessible | Nanoseconds to microseconds [8] [19] | Microseconds to milliseconds or beyond [8] |

| Computational Efficiency | Baseline (1x) | 3+ orders of magnitude acceleration [19] |

| Accuracy Trade-off | High structural fidelity | Sacrifices atomic-level accuracy [8] |

| Typical Applications | Detailed mechanism studies, ligand binding | Large conformational changes, large complexes [18] |

| Solvent Treatment | Explicit solvent molecules | Implicit solvent or simplified explicit models [18] |

Table 2: Performance Data from Polymer Simulation Studies [20]

| Model Type | Spatial Scaling Factor | Temporal Scaling Factor | Computational Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bead-Spring Kremer-Grest (KG) Model | Defined via mapping | Defined via mapping | Quantitative gains estimated via scaling factors |

| Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) | Cutoff radius (r(_c)) as unit | Reduced units | Significant acceleration compared to AA |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Protocol

AA simulations employ Newtonian mechanics with detailed force fields. The methodology involves [20]:

- System Setup: Placing the molecular system in explicit solvent molecules within a periodic boundary box.

- Force Field Application: Using potentials that account for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatic).

- Integration: Solving equations of motion with femtosecond time steps using algorithms like Velocity Verlet.

- Thermostatting: Maintaining temperature using thermostats like Nosé-Hoover or Berendsen.

- Data Collection: Tracking coordinates and energies over time for subsequent analysis.

Coarse-Grained Model Development and Simulation

Resolution Mapping

CG models reduce system complexity by grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites:

- Proteins: Typically one bead per amino acid centered at the Cα atom position [18].

- Nucleic Acids: Often represented with three beads per nucleotide (phosphate, sugar, base) [18].

- Mapping: Approximately 10 heavy atoms are represented by a single CG particle [18].

Interaction Potentials

CG models use simplified potential functions:

- Bonded Interactions: Harmonic bonds and angles (Eqs. 1-3 in [18])

- Non-bonded Interactions: Repulsive Lennard-Jones potentials (Eq. 1 in [20]) or soft conservative forces in DPD (Eq. 6 in [20])

- Specialized Terms: Knowledge-based potentials for specific biomolecules or processes

Dynamics Propagation

CG simulations often use Langevin dynamics or Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD):

- Langevin Equation: Includes friction and random forces (Eq. 3-4 in [20])

- DPD Equations: Employ conservative, dissipative, and random forces (Eq. 5-9 in [20])

- Timestep: Allows larger integration steps than AA models

Machine Learning Approaches in Coarse-Graining

Recent advances integrate machine learning to develop CG potentials:

- Neural Network Potentials (NNPs): Train on AA data to learn effective CG force fields [19]

- Force Matching: Minimize loss between CG and mapped AA forces (Eq. 1 in [19])

- Multi-Protein Potentials: Single NNP can integrate multiple proteins, enabling transferability [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Biomolecular Simulations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENESIS [18] | MD Software | All-atom and coarse-grained simulations | Optimized for CG simulations, unified treatment of proteins/nucleic acids |

| LAMMPS [18] | MD Simulator | General-purpose particle modeling | Extensive CG model compatibility |

| GROMACS [18] | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics | All-atom and CG capability |

| GENESIS-CG-tool [18] | Toolbox | Input file generation for CG simulations | User-friendly preparation of complex systems |

| CafeMol [18] | CG Software | Specialized coarse-grained simulations | Structure-based models |

Visualizing the Multi-Scale Bridging Approach

The choice between atomistic and coarse-grained approaches depends fundamentally on research goals. AA models remain essential for investigating atomic-level mechanisms, ligand binding, and detailed conformational changes where chemical specificity is crucial. CG models enable the study of large-scale biomolecular processes, including chromatin folding, viral capsid assembly, and phase-separated membrane-less condensations [18]. The integration of machine learning with coarse-graining represents a promising direction, creating potentials that preserve thermodynamics while dramatically accelerating simulations [19]. By understanding these trade-offs and utilizing appropriate scaling methodologies, researchers can strategically select simulation approaches that balance atomic detail against computational efficiency for their specific biological questions.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded for the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), highlights a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry: how to simulate complex, porous materials that operate across vast spatial and temporal scales [21] [22]. MOFs exemplify this challenge—their extraordinary properties emerge from intricate molecular architectures containing enormous internal surface areas, where one gram can exhibit the surface area of a football pitch [23]. Understanding these systems requires computational approaches that can capture atomic-level interactions while simulating phenomena at mesoscopic scales. This challenge frames the critical comparison between atomistic and coarse-grained potential models in computational chemistry and drug development. While all-atom models provide exquisite detail, their computational demands render them impractical for simulating the very phenomena that make MOFs technologically valuable—gas storage, molecular separation, and catalytic processes occurring in nanoscale pores [8] [1]. Coarse-grained models address this limitation through strategic simplification, grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites to access biologically and technologically relevant time and length scales [8] [24]. This review examines the theoretical foundations and modern implementations of these complementary approaches, providing researchers with a comprehensive comparison of their capabilities, limitations, and optimal applications in biomolecular simulation and drug development.

Methodological Frameworks: From Quantum Mechanics to Machine Learning

All-Atom (AA) Molecular Dynamics

All-atom molecular dynamics simulations represent the highest resolution approach in classical molecular modeling, explicitly representing every atom in a system. These simulations numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion using femtosecond time steps, providing detailed insights at atomistic resolution [6]. The accuracy of AA predictions primarily depends on force field quality, with specialized parameterizations developed for specific applications like ionic liquids (e.g., APPLE&P, AMOEBA-based, CL&P, GAFF-based, SAPT-based, and OPLS-based force fields) [1]. AA simulations can capture subtle conformational changes, specific molecular recognition events, and detailed interaction networks, making them indispensable for studying mechanisms requiring atomic precision, such as enzyme catalysis or drug-receptor binding [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of All-Atom Molecular Dynamics

| Feature | Description | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Explicit representation of all atoms | Computational expensive |

| Time Scale | Femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) to nanoseconds | Limited to short timescales |

| Length Scale | Nanometers to tens of nanometers | Small system sizes |

| Force Fields | OPLS, AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS | Parameterization challenges |

| Applications | Detailed mechanistic studies, binding interactions | Poor efficiency for large conformational changes |

Coarse-Grained (CG) Models

Coarse-grained models extend simulation capabilities by reducing molecular complexity, grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites or "beads." This simplification smooths high-frequency atomic vibrations and flattens the free-energy landscape, reducing molecular friction and enabling faster exploration of conformational space [1]. CG models typically allow larger time steps (10-20 fs) compared to AA models (1-2 fs), significantly accelerating simulations [1]. The development of CG models involves two critical steps: (1) defining the CG mapping scheme that determines how atoms are grouped into beads, and (2) parameterizing effective interaction potentials for these beads [24].

Table 2: Coarse-Grained Model Development Approaches

| Approach | Methodology | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Top-Down | Parameters fitted to macroscopic experimental properties | MARTINI model |

| Bottom-Up | Utilizes statistical mechanics to preserve microscopic properties of atomistic models | IBI, IMC, MS-CG, RE, ECRW |

| Hybrid | Combines bottom-up methods for bonded terms with empirical adjustment of nonbonded terms | Many ionic liquid CG models |

The fundamental workflow for developing systematic coarse-grained models begins with validated all-atom simulations, which provide reference data for constructing CG representations. Bottom-up methods like iterative Boltzmann inversion (IBI) then derive effective potentials that reproduce the structural distributions of the atomistic reference system [24]. This systematic linking of methodologies across scales enables quantitative prediction of molecular behavior over broad spatiotemporal ranges.

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) and Force Matching

Machine learning has revolutionized coarse-graining through the development of ML potentials (MLPs) that approximate the potential of mean force (PMF) in CG models [25]. These models are typically trained using bottom-up approaches like variational force matching, where the MLP learns to minimize the mean squared error between predicted CG forces and atomistic forces projected onto CG space [6] [25]. The force matching objective can be expressed as:

[ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \langle \| M{\mathfrak{f}}\mathfrak{f}(r) - \hat{F}{\theta}(Mr) \|_2^2 \rangle ]

where (M{\mathfrak{f}}\mathfrak{f}(r)) represents the projected all-atom forces and (\hat{F}{\theta}(Mr)) denotes the CG force field with parameters (\theta) [6]. Recent innovations address the significant data requirements of traditional force matching by incorporating enhanced sampling techniques that bias along CG degrees of freedom for more efficient data generation while preserving the correct PMF [25]. Normalizing flows and other generative models have also been employed to create more general kernels that reduce local distortions while maintaining global conformational accuracy [6].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance

The performance differential between AA and CG models becomes evident when examining their ability to reproduce experimental observables. Ionic liquids provide an excellent case study, as their high viscosity presents particular challenges for atomistic simulations [1].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Models for [C₄mim][BF₄] Ionic Liquid

| Model Type | Specific Model | Density (kg/m³) | Diffusion Coefficient (10⁻¹¹ m²/s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG Models | MARTINI-based | 1181 (300 K) | 120/145 (293 K) | [1] |

| Top-down | 1209 (298 K) | 1.12/0.59 (298 K) | [1] | |

| ECRW | 1173 (300 K) | 1.55/1.74 (313 K) | [1] | |

| ML Potential | — | 48.58/35.49 (300 K) | [1] | |

| AA Models | OPLS | 1178 (298 K) | 7.3/6.6 (425 K) | [1] |

| 0.8*OPLS | 1150 (298 K) | 43.1/42.9 (425 K) | [1] | |

| SAPT-based | 1180 (298 K) | 1.1/0.8 (298 K) | [1] | |

| CL&P | 1154 (343 K) | 1.19/0.88 (343 K) | [1] | |

| Experimental | — | 1170 (343 K) | 40.0/47.6 (425 K) | [1] |

The data reveals several important trends: (1) CG models can accurately reproduce structural properties like density; (2) diffusion coefficients show greater variation between models, with some CG approaches actually outperforming certain AA force fields; and (3) machine learning potentials show particular promise for capturing dynamic properties while maintaining computational efficiency [1].

Application to Biomolecular Systems

In biomolecular simulations, AA models provide unparalleled detail for studying specific interactions but face severe limitations in capturing large-scale conformational changes or assembly processes. CG models enable the study of membrane remodeling, protein folding, and molecular transport phenomena that occur on micro- to millisecond timescales [8] [6]. For example, simulating individual miniproteins with machine learning coarse-graining requires approximately one million reference configurations, highlighting both the data requirements and extended capabilities of these approaches [6].

Polymer systems exemplify the practical advantages of coarse-graining for industrially relevant applications. Research on poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), a biodegradable polymer with applications in tissue engineering and 3D printing, demonstrates how CG models enable the investigation of chain length effects from unentangled to mildly-entangled systems (10 to 125 monomers)—a range critically important for industrial applications but prohibitively expensive for AA simulation [24]. The systematic CG approach accurately reproduces structural and dynamic properties while dramatically improving computational efficiency [24].

Advanced Protocols and Experimental Methodologies

Systematic Coarse-Graining Protocol for Polymers

The development of reliable CG models follows rigorous methodologies. For PCL polymer melts, researchers employed a detailed protocol beginning with all-atom simulations using the L-OPLS force field, an adaptation of OPLS-AA optimized for long hydrocarbon chains [24]. The methodology proceeds through several validated stages:

Atomistic Reference Simulations: Initial AA simulations of PCL chains across multiple molecular weights (10-125 monomers) provide benchmark data for structural and dynamic properties [24].

Validation Against Experimental and Theoretical Predictions: Atomistic simulation results are rigorously compared with existing literature data and theoretical predictions to ensure validity before CG model development [24].

CG Mapping Definition: A monomer-level mapping scheme groups atoms into single beads, establishing correspondence between atomistic and reduced resolutions [24].

Potential Derivation via IBI: The iterative Boltzmann inversion method derives effective interaction potentials that match local structural distributions from the atomistic reference system [24].

This systematic approach ensures the resulting CG model maintains physical fidelity while extending simulation capabilities to experimentally relevant scales [24].

Enhanced Sampling for Machine Learning Potentials

A fundamental limitation of traditional force matching is its reliance on unbiased equilibrium sampling, which often poorly samples transition regions between metastable states [25]. Recent advances address this through enhanced sampling techniques:

Biased Trajectory Generation: Enhanced sampling methods apply a bias potential along coarse-grained coordinates to accelerate exploration of configuration space [25].

Unbiased Force Computation: Forces are recomputed with respect to the unbiased atomistic potential, preserving the correct potential of mean force [25].

MLP Training: The biased trajectories with corrected forces provide training data for machine learning potentials, significantly improving data efficiency and coverage of transition states [25].

This methodology has demonstrated notable improvements for both model systems like the Müller-Brown potential and biomolecular systems such as capped alanine in explicit water [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of multiscale simulation strategies requires familiarity with both theoretical frameworks and practical computational tools. The following table summarizes key resources for researchers developing and applying coarse-grained models.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Coarse-Grained Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | MARTINI [1], APPLE&P [1], OPLS-AA [24], L-OPLS [24] | Define interaction potentials between particles | MD simulations across resolutions |

| Parameterization Methods | Iterative Boltzmann Inversion (IBI) [24], Multiscale Coarse-Graining (MS-CG) [6], Relative Entropy Minimization [6] | Derive effective potentials for CG models | Bottom-up coarse-graining |

| Sampling Algorithms | Metadynamics [25], Umbrella Sampling [25], Enhanced Sampling [25] | Accelerate configuration space exploration | Improved sampling for ML training |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Force Matching [6] [25], Normalizing Flows [6], Denoising Score Matching [6] | Learn CG potentials from atomistic data | ML-driven coarse-graining |

| Simulation Software | GROMACS [24], LAMMPS, OpenMM | Perform molecular dynamics simulations | AA and CG trajectory generation |

The theoretical foundations spanning from Nobel Prize-winning materials to modern implementations reveal a sophisticated ecosystem of multiscale modeling approaches. All-atom models remain indispensable for detailed mechanistic studies requiring atomic resolution, while coarse-grained models provide access to biologically and technologically relevant scales that would otherwise remain inaccessible [8] [24]. The integration of machine learning, particularly through force matching and enhanced sampling protocols, has dramatically improved the accuracy and efficiency of CG models while addressing longstanding challenges in parameterization and transferability [6] [25].

For researchers and drug development professionals, strategic model selection depends critically on the specific scientific question. AA models excel for detailed binding interactions, enzyme mechanisms, and subtle conformational changes where atomic precision is paramount. CG models enable the study of large-scale structural transitions, molecular assembly, and diffusion-limited processes that occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales [8] [1]. The most powerful modern approaches combine these methodologies, using ML-driven coarse-graining to maintain thermodynamic consistency while extending simulation capabilities [6] [25]. As these integrated methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to unlock new frontiers in molecular design, drug discovery, and functional material development—from the atomic-scale precision of Nobel Prize-winning frameworks to the mesoscale phenomena that define their technological utility.

Methodologies in Action: From CG Mapping to Machine Learning Potentials

In computational chemistry and drug development, the conflict between simulation accuracy and temporal-spatial scale represents a fundamental challenge. Atomistic (AA) models provide exquisite detail by representing every atom but become computationally prohibitive for studying biological processes at microsecond timescales or for large systems like lipid membranes and protein complexes. Coarse-grained (CG) models address this limitation through strategic simplification, grouping multiple atoms into single interaction sites called "beads" to dramatically reduce system complexity. This systematic reduction of degrees of freedom enables scientists to access biologically relevant timescales and system sizes while preserving essential physical characteristics, creating an indispensable tool for studying complex molecular phenomena in drug delivery systems, membrane dynamics, and material science.

CG Mapping Schemes: Fundamental Approaches and Methodologies

Core Principles of Coarse-Graining

Coarse-grained mapping operates on the fundamental principle of reducing molecular complexity while preserving essential physical behavior. The process begins with selecting a specific CG resolution, determining how many heavy atoms are represented by each CG bead. Common mapping schemes include 2:1 (two atoms per bead), 3:1, or 4:1 ratios, with higher ratios providing greater computational efficiency at the potential cost of chemical detail. The CG mapping scheme defines which atoms are grouped into each bead, typically based on chemical intuition or systematic methods including relative entropy theory, autoencoder techniques, and graph neural networks [1]. This grouping smoothes high-frequency atomic vibrations and flattens the free-energy landscape, reducing molecular friction and enabling faster exploration of configuration space [1].

Force Field Parameterization Strategies

Once the mapping scheme is established, molecular interactions are described through coarse-grained force fields comprising bonded and nonbonded terms. Two primary philosophical approaches dominate CG force field development:

Bottom-up methods derive parameters from atomistic simulations or quantum mechanical calculations to preserve microscopic properties of the underlying system. Key methodologies include Inverse Boltzmann Inversion (IBI), Inverse Monte-Carlo (IMC), Multiscale Coarse-Graining (MS-CG), Relative Entropy (RE) minimization, and Extended Conditional Reversible Work (ECRW) approaches [1]. These methods utilize statistical mechanics principles to maintain consistency with finer-grained models.

Top-down methods parameterize CG models directly against experimental macroscopic properties such as density, membrane thickness, or diffusion coefficients, providing accurate thermodynamic behavior but potentially less transferability across different chemical environments [1].

In practice, many modern CG models adopt a hybrid approach, using bottom-up methods for bonded terms while optimizing nonbonded parameters against experimental data to balance transferability with experimental accuracy [1] [26].

Comparative Analysis: CG Mapping Schemes and Performance

Table 1: Performance comparison of selected coarse-grained models for ionic liquids ([C4mim][BF4])

| Model Type | Model Name | Density (kg/m³) | Cation Diffusion (10⁻¹¹ m²/s) | Anion Diffusion (10⁻¹¹ m²/s) | Conductivity (S/m) | Heat of Vaporization (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG Models | MARTINI-based | 1181 (300K) | 120 (293K) | 145 (293K) | — | — |

| Top-down | 1209 (298K) | 1.12 (298K) | 0.59 (298K) | — | — | |

| ECRW | 1173 (300K) | 1.55 (313K) | 1.74 (313K) | — | — | |

| Drude-based | — | 5.8 (350K) | 7.3 (350K) | 17 (350K) | 114 (350K) | |

| VaCG | 1168 (303K) | 1.20 (303K) | 0.53 (303K) | 0.45 (303K) | 123.51 (303K) | |

| AA Models | OPLS | 1178 (298K) | 7.3 (425K) | 6.6 (425K) | — | 125.52 (298K) |

| 0.8*OPLS | 1150 (298K) | 43.1 (425K) | 42.9 (425K) | — | 140.5 (298K) | |

| SAPT-based | 1180 (298K) | 1.1 (298K) | 0.8 (298K) | 0.29 (298K) | 126 (298K) | |

| CL&P | 1154 (343K) | 1.19 (343K) | 0.88 (343K) | — | — | |

| APPLE&P | 1193 (298K) | 1.01 (298K) | 1.05 (298K) | 0.28 (298K) | 140.8 (298K) | |

| Experimental | Reference | 1170 (343K) | 40.0 (425K) | 47.6 (425K) | 2.17 (350K) | 128.03 (303K) |

Table 2: CG mapping schemes and their applications across molecular systems

| CG Model | Mapping Resolution | System Type | Parameterization Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARTINI | 2:1 to 4:1 | Lipids, Proteins, Polymers | Top-down (experimental partition coefficients) | High computational efficiency, extensive community use | Limited chemical specificity, transferability challenges |

| MS-CG | Variable | Ionic liquids, Biomolecules | Bottom-up (force-matching) | Systematic connection to atomistic forces | Requires extensive AA simulations for parameterization |

| ECRW | 2:1 to 3:1 | Ionic liquids | Bottom-up (conditional reversible work) | Accurate local structure reproduction | Limited electrostatic representation |

| Drude-based Polarizable | 2:1 to 3:1 | Ionic liquids, Polar systems | Hybrid (bottom-up with polarizability) | Explicit polarization effects | Increased computational cost |

| Structure-based Lipid CG | 2:1 or 3:1 | Phosphocholine lipids | Hybrid (structural and elastic properties) | Reproduces membrane mechanics | No explicit electrostatics in current implementation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Development of Transferable Coarse-Grained Lipid Models

The development of CG models for phosphocholine lipids illustrates a systematic hybrid approach balancing computational efficiency with predictive accuracy. Researchers have established a rigorous protocol employing 2:1 or 3:1 mapping schemes where related atoms are grouped into single beads based on chemical functionality [26]. The model optimization utilizes Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm integrated with molecular dynamics simulations, simultaneously targeting structural properties (lipid packing density, membrane thickness from X-ray/neutron scattering) and elastic properties (bending modulus from neutron spin echo spectroscopy) [26]. This dual focus ensures the models capture both equilibrium structure and mechanical response. Validation includes comparison with atomistic simulations for bond/angle distributions and radial distribution functions, followed by assessment of transferability across lipid types (DOPC, POPC, DMPC) and temperatures [26].

Computational Functional Group Mapping (cFGM) for Drug Discovery

In drug discovery, computational functional group mapping (cFGM) represents a specialized CG approach that identifies favorable binding regions for molecular fragments on protein targets. The methodology involves all-atom explicit-solvent MD simulations with probe molecules (e.g., isopropanol, acetonitrile, chlorobenzene) representing different functional groups [27]. These simulations naturally incorporate target flexibility and solvent competition, detecting both high-affinity binding sites and transient low-affinity interactions. The resulting 3D probability maps, visualized at ~1Å resolution, guide medicinal chemists in designing synthetically accessible ligands with optimal complementarity to their targets [27]. This approach provides advantages over experimental fragment screening by detecting low-affinity regions and preventing aggregation artifacts while mapping the entire target surface simultaneously for multiple functional groups.

Visualization: CG Model Development Workflow

CG Model Development Workflow

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for CG model development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics simulations | CG model simulation, parameter testing, production runs |

| NAMD | MD Software | Scalable molecular dynamics | Large system CG simulations, membrane systems |

| MARTINI | CG Force Field | Pre-parameterized coarse-grained models | Biomolecular simulations, lipid membranes, polymers |

| MS-CG | Parameterization Method | Bottom-up force field development | Systematic CG model creation from AA simulations |

| VMD | Visualization Software | Molecular visualization and analysis | CG trajectory analysis, mapping visualization |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Optimization Algorithm | Multi-parameter optimization | Force field parameter refinement against experimental data |

| GEBF Approach | QM Fragmentation Method | Quantum mechanical calculations for large systems | Polarizable CG model parameterization |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The evolution of coarse-grained methodologies continues to address several fundamental challenges. Polarization effects remain particularly difficult to capture accurately in CG models, with current approaches including Drude oscillators, fluctuating charge models, and fragment-based QM methods like the Generalized Energy-Based Fragmentation (GEBF) approach [1]. Transferability across different chemical environments and temperatures represents another significant hurdle, with promising developments including variable electrostatic parameters that implicitly adapt to different polarization environments [1]. The integration of machine learning techniques offers transformative potential through ML-surrogate models for force field parameterization and the development of ML potentials that can capture complex many-body interactions without explicit functional forms [1]. As these methodologies mature, CG models will expand their applicability to increasingly complex biological and materials systems, further bridging the gap between atomic detail and mesoscopic phenomena.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful tool for investigating biological processes at a molecular level. However, the computational cost of all-atom (AA) simulations often limits the accessible time and length scales, preventing the study of many biologically important phenomena. Coarse-grained (CG) models address this challenge by representing groups of atoms as single interaction sites, thereby reducing the number of degrees of freedom in the system. This simplification allows for larger timesteps and much longer simulation times, enabling the study of large-scale conformational changes, protein folding, and membrane remodeling processes that are beyond the reach of atomistic simulation [13] [28]. The core physical basis of coarse-grained molecular dynamics is that the motion of CG sites is governed by the potential of mean force, with additional friction and stochastic forces resulting from integrating out the secondary degrees of freedom [13].

This guide provides an objective comparison of three popular CG frameworks: the MARTINI model, Gō-like models, and the Associative memory, Water mediated, Structure and Energy Model (AWSEM). We evaluate their performance, applications, and limitations within the broader context of atomistic versus coarse-grained potential model comparison research, providing supporting experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Gō Models: Structure-Based Simplicity

Gō models are structure-based models that bias the protein toward its known native folded state using native interactions derived from experimental structures [29]. They operate on the principle that a protein's native structure is the global minimum of a funneled energy landscape. The key characteristic of Gō models is their simplified energy landscape, which facilitates efficient sampling of protein folding and large-scale conformational changes.

- Resolution Variants: Gō models exist at different resolution levels, including Cα-based models (one interaction site per amino acid), heavy-atom models (all non-hydrogen atoms), and hybrid models like Gō-MARTINI that combine Gō interactions with the MARTINI force field [29] [30] [28].

- Recent Enhancements: The recently developed GōMartini 3 model combines a virtual-site implementation of Gō models with Martini 3, demonstrating capabilities in diverse case studies ranging from protein-membrane binding to protein-ligand interactions and AFM force profile calculations [30].

AWSEM: Balanced Transferability

The Associative memory, Water mediated, Structure and Energy Model (AWSEM) represents a middle-ground approach with three interaction sites per amino acid [29]. AWSEM incorporates both structure-based elements and physics-based interactions, aiming for better transferability than pure Gō models while maintaining computational efficiency compared to all-atom simulations.

- Energy Function: AWSEM includes terms for associative memory (structural biases), water-mediated interactions, and general physicochemical properties, creating a balanced force field that can capture aspects of protein folding and binding without being exclusively tied to a single native structure [29].

- Application Scope: While less widely adopted than MARTINI, AWSEM has been particularly useful for studying protein folding mechanisms and protein-protein interactions where some transferability is required but all-atom resolution remains prohibitive.

MARTINI: Versatile and Physics-Based

The MARTINI model is one of the most popular CG force fields, known for its versatility in simulating various biomolecular systems, including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids [31] [28]. Unlike structure-based Gō models, MARTINI is primarily a physics-based model parameterized to reproduce experimental partitioning free energies between polar and apolar phases [31].

- Mapping Scheme: MARTINI typically represents approximately four heavy atoms with one CG bead, maintaining chemical specificity while significantly reducing system complexity.

- Recent Developments: The latest version, Martini 3, offers improved accuracy in representing molecular interactions and has demonstrated remarkable success in simulating spontaneous protein-ligand binding events, including accurate prediction of binding pockets and pathways without prior knowledge [31].

- Hybrid Approaches: The Gō-MARTINI model combines MARTINI with structure-based Gō interactions, enabling the study of large conformational changes in proteins within biologically relevant environments [28].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Popular Coarse-Grained Frameworks

| Framework | Resolution | Energy Function Basis | Transferability | Computational Speed vs AA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gō Models | Cα to heavy atoms | Structure-based (native contacts) | Low (system-specific) | Several orders of magnitude faster |

| AWSEM | 3 beads per amino acid | Mixed (structure + physics-based) | Moderate | Significantly faster |

| MARTINI | ~4 heavy atoms per bead | Physics-based (partitioning) | High | Several orders of magnitude faster |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Validation

Mechanical Unfolding and Force Spectroscopy

A systematic study comparing CG models for force-induced protein unfolding provides valuable insights into their relative strengths and limitations. Research on the mechanical unfolding of loop-truncated superoxide dismutase (SOD1) protein via simulated force spectroscopy compared all-atom models with several CG approaches [29].

Table 2: Performance in Simulated Force Spectroscopy of Protein Unfolding [29]

| Model | Force Peak Agreement with AA | Unfolding Pathway Similarity | Native Contact Breakage Prediction | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom | Reference | Reference | Reference | Computationally expensive |

| Heavy-Atom Gō | Softest protein, smallest force peaks | High for early unfolding, diverges later | Best prediction among CG models | Limited transferability |

| Cα-Gō | Good after renormalization | High for early unfolding, diverges later | Moderate | Oversimplified late unfolding |

| AWSEM | Good after renormalization | Single pathway (differs from AA bifurcating) | Least accurate at low nativeness | Poor late-stage unfolding |

| MARTINI | Not specifically tested in this study | Not specifically tested in this study | Not specifically tested in this study | Not specifically tested |

The study revealed that while all CG models successfully captured early unfolding events of nearly-folded proteins, they showed significant limitations in describing the late stages of unfolding when the protein becomes mostly disordered [29]. This highlights a common challenge in CG modeling: the balance between computational efficiency and accurate representation of disordered states.

Protein Folding and Conformational Landscapes

The ability to predict protein folding mechanisms and conformational landscapes varies considerably across CG frameworks:

- Gō Models: Excel at describing folding pathways toward known native structures but have limited ability to discover novel folds or accurately represent non-native interactions.

- AWSEM: Shows promise in capturing folding mechanisms, though in the SOD1 unfolding study, it displayed a single dominant unfolding pathway in contrast to the multiple pathways observed in all-atom simulations [29].

- MARTINI: When combined with Gō interactions (Gō-MARTINI), can simulate large conformational changes. However, the standard MARTINI with elastic network often restricts large-scale motions unless specifically modified [28].

- Machine-Learned CG Models: Recent advances in machine learning have enabled the development of transferable bottom-up CG force fields that can successfully predict metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures, with demonstrated ability to simulate proteins not included during training [15].

Protein-Ligand and Protein-Membrane Interactions

Different CG frameworks show varying capabilities in modeling molecular interactions:

- MARTINI: Demonstrates remarkable success in protein-ligand binding studies. Recent research shows that MARTINI 3 can accurately predict binding pockets and pathways for various protein-ligand systems, including T4 lysozyme mutants, GPCRs, and kinases, with binding free energies in very good agreement with experimental values (mean absolute error of 1 kJ/mol) [31].

- Gō-MARTINI: Has been optimized for protein-membrane systems, successfully reproducing structural fluctuations of F-BAR proteins on lipid membranes and their proper assembly through lateral interactions [28].

- AWSEM: Its performance in specific protein-ligand or protein-membrane interactions is less documented in the available literature compared to MARTINI.

Technical Implementation and Experimental Protocols

Common Simulation Methodologies

The experimental protocols for implementing CG simulations share common elements across frameworks, though specific parameters vary:

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) for Force Spectroscopy:

- Terminal Pulling: Both termini are tethered with a harmonic potential, with the C-terminus moved along the vector from C- to N-terminus with constant velocity [29].

- Pulling Speeds: Typically faster (1-1000 m/s) than experimental AFM speeds (10−8-10−2 m/s) due to computational constraints [29].

- Spring Constants: Commonly set to 1000 kJ/(mol · nm²) for the pulling force [29].

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Unbiased Sampling: For MARTINI protein-ligand binding, ligands are initially positioned randomly in solvent, with millisecond-scale sampling performed to observe spontaneous binding events [31].

- Free Energy Estimation: Binding free energies ((\Delta G_{bind})) are calculated by integrating one-dimensional potentials of mean force from density distributions [31].

System Setup:

- Solvation: CG water models (e.g., MARTINI water) are used with appropriate ion concentrations for electroneutrality [32].

- Membrane Construction: For membrane systems, mixed lipid bilayers are constructed using tools like CHARMM-GUI or insane.py, with proteins properly positioned and oriented on the membrane [28].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for CG Simulations

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Running production CG simulations [28] |

| CHARMM-GUI | Biomolecular system building | Creating membrane-protein systems [28] |

| MARTINI Force Field | Physics-based CG interactions | Protein-ligand binding, membrane systems [31] |

| Gō-MARTINI Parameters | Structure-based CG interactions | Large conformational changes in proteins [28] |

| VMD | System visualization and analysis | Trajectory analysis, structure visualization [28] |

| TIP3P Water Model | All-atom water for reference simulations | Target for CG model development [29] |

Integration Pathways and Relationship Between Modeling Approaches

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between different modeling approaches and their applications, highlighting how they complement each other across scales:

Each coarse-grained framework offers distinct advantages for specific research applications. Gō models provide the most computationally efficient approach for studying protein folding and mechanical unfolding when the native structure is known, but suffer from limited transferability. AWSEM offers a balance between specificity and transferability with its intermediate resolution. MARTINI demonstrates remarkable versatility and accuracy in protein-ligand binding predictions, particularly with the recent Martini 3 implementation.

The future of coarse-grained modeling appears to be moving toward hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different frameworks, such as Gō-MARTini, and machine-learned force fields that offer the promise of quantum-mechanical accuracy at CG computational cost [15] [8]. As these methods continue to mature, they will increasingly enable researchers and drug development professionals to tackle biologically complex problems at unprecedented scales, from cellular processes to drug mechanism elucidation, effectively bridging the gap between all-atom detail and biological relevance.