Engineering Synergistic Yeast Consortia for De Novo Lignan Biosynthesis

This article explores the groundbreaking application of synthetic yeast consortia for the de novo biosynthesis of valuable plant lignans.

Engineering Synergistic Yeast Consortia for De Novo Lignan Biosynthesis

Abstract

This article explores the groundbreaking application of synthetic yeast consortia for the de novo biosynthesis of valuable plant lignans. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how dividing complex metabolic pathways across engineered, mutually dependent yeast strains overcomes long-standing challenges in metabolic engineering. We cover the foundational principles of microbial syntrophy, the methodological construction of consortia for producing compounds like pinoresinol and antiviral lariciresinol diglucoside, key troubleshooting strategies for optimizing metabolic flux and co-factor supply, and a comparative analysis validating the efficiency of this approach against traditional plant extraction and single-strain fermentation. This synthesis biology strategy heralds a new era for the sustainable and scalable production of complex plant-derived therapeutics.

Lignans and the Synthetic Biology Imperative: Why Yeast Consortia?

Plant lignans, a class of low molecular weight polyphenolic compounds, have garnered significant scientific interest for their potent biological activities, particularly their antiviral and antitumor properties. These compounds, found in various plants like flaxseed and Schisandra chinensis, present promising therapeutic potential but face challenges in sustainable supply due to low extraction yields and structural complexity. Recent breakthroughs in synthetic biology have demonstrated the feasibility of reconstructing lignan biosynthetic pathways in synthetic yeast consortia with obligated mutualism, enabling de novo production of complex lignans including antiviral glycosides. This whitepaper comprehensively reviews the therapeutic mechanisms of plant lignans against viral infections and cancer, while framing these advances within the context of innovative bioproduction platforms that mimic the metabolic division of labor in plant multicellular systems. The integration of cutting-edge biosynthesis methodologies with detailed mechanistic understanding of lignan bioactivity provides a robust foundation for future pharmaceutical development and clinical applications.

Lignans are diphenolic compounds formed by the stereospecific dimerization of two coniferyl alcohol residues, classified as polyphenolic secondary metabolites with diverse chemical structures and biological activities [1]. These ubiquitous plant compounds serve important ecological functions while offering significant therapeutic potential for human health. The fundamental chemical structure consists of two phenylpropanoid (C6-C3) units linked by a β-β' bond, though structural diversity arises from various oxidative patterns and additional ring formations [2] [1].

The biosynthetic pathway of lignans in plants begins with the conversion of phenylalanine to cinnamic acid, leading to the production of coniferyl alcohol [3] [4]. Dirigent proteins then mediate the stereospecific coupling of two coniferyl alcohol molecules to form pinoresinol, the central precursor to most lignans [1]. Sequential enantiospecific reductions catalyzed by pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase generate lariciresinol and subsequently secoisolariciresinol (SECO) [3] [4]. Further modifications including glycosylation, hydroxylation, and methylation produce the diverse array of lignans found in nature, with secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) representing a major storage form in seeds such as flaxseed [1].

Upon ingestion by humans, plant lignans undergo extensive biotransformation by gut microbiota. The intestinal bacteria hydrolyze glycosidic bonds (e.g., converting SDG to SECO), followed by dehydroxylation and demethylation reactions that produce the enterolignans—enterodiol (ED) and enterolactone (EL)—often referred to as mammalian lignans [1]. These metabolites exhibit structural similarity to estradiol, enabling them to interact with estrogen receptors and modulate hormonal pathways, classifying them as phytoestrogens with significant implications for hormone-related cancers and metabolic conditions [1].

Antiviral Properties and Mechanisms of Action

Direct Antiviral Activity Against Specific Pathogens

Recent research has unveiled the potent antiviral properties of various lignans, with particular promise demonstrated against the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV). A 2025 study employed virtual screening to identify lignan compounds targeting FMDV's RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol), a highly conserved enzyme crucial for viral replication across all FMDV serotypes [5]. The investigation revealed that (-)-asarinin and sesamin exhibit significant inhibition effects in post-viral entry assays, with EC50 values of 15.11 μM and 52.98 μM, respectively [5]. Both compounds demonstrated dose-dependent reduction in viral replication with substantial suppression of negative-strand RNA production, confirming their mechanism involves disruption of the viral replication machinery.

The antiviral efficacy of these lignans was further validated through a cell-based FMDV minigenome assay, which specifically assessed their ability to target FMDV 3Dpol [5]. (-)-Asarinin demonstrated remarkable inhibition of GFP expression with an IC50 value of 10.37 μM, while sesamin required higher concentrations for similar effects, indicating differences in potency despite shared mechanisms [5]. Molecular docking studies revealed that these lignans preferentially bind to the active site of FMDV 3Dpol, particularly interacting with catalytic residues in the palm subdomains (Motif A and C), including Asp240, Asp245, Asp338, and Asp339, which are essential for polymerase functionality [5].

Beyond FMDV, lignans have demonstrated broad-spectrum antiviral potential. Lariciresinol diglucoside has shown significant antiviral activity, prompting its selection for biosynthesis in engineered yeast systems [3] [4] [6]. Similarly, various lignans from Schisandra chinensis, including schisandrin, schisandrin B, and gomisins, have exhibited antiviral properties against diverse viral pathogens, though their specific molecular targets require further elucidation [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Lignan Antiviral Efficacy

Table 1: Antiviral Activity of Selected Lignans Against FMDV

| Lignan Compound | EC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | Therapeutic Index | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (-)-Asarinin | 15.11 | 10.37 | >100 | >6.6 | FMDV 3Dpol inhibition |

| Sesamin | 52.98 | >50 | >100 | >1.9 | FMDV 3Dpol inhibition |

| Lariciresinol diglucoside* | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Antiviral (specific mechanism not detailed) |

Note: EC50 = half-maximal effective concentration; IC50 = half-maximal inhibitory concentration; CC50 = half-maximal cytotoxic concentration; Therapeutic Index = CC50/EC50; *Data from yeast consortia biosynthesis studies [3] [5] [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of Antiviral Action

The primary antiviral mechanism of lignans involves targeted inhibition of viral replication enzymes, particularly RNA-dependent RNA polymerases essential for viral genome replication. For FMDV, this occurs through precise molecular interactions where lignans bind to the active site of 3Dpol, disrupting its catalytic function [5]. Additional mechanisms may include modulation of host cell pathways and immune responses, as suggested by the documented anti-inflammatory properties of various lignans [2] [1]. The multifaceted nature of lignan bioactivity suggests potential for broad-spectrum antiviral applications, though compound-specific mechanisms require continued investigation.

Figure 1: Antiviral Mechanism of Lignans Against FMDV. Lignans directly bind to the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3Dpol) active site, inhibiting replication.

Antitumor Properties and Cancer Mechanisms

Multifaceted Anticancer Activities

Lignans exhibit compelling antitumor properties through diverse mechanisms, positioning them as promising candidates for cancer prevention and adjunct therapy. The dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans from Schisandra chinensis, including schisandrin, schisandrin A, schisandrin B, schisandrin C, and various gomisins (A, B, C, G, J, K3), have demonstrated significant anticancer potential against multiple cancer types [2]. These compounds exert their effects through modulation of oxidative stress, inhibition of inflammatory signaling pathways, and regulation of apoptosis in malignant cells.

Flaxseed lignans, particularly secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) and its mammalian metabolites enterodiol (ED) and enterolactone (EL), have shown notable chemopreventive and therapeutic activities [1] [7]. Their structural similarity to estradiol enables interaction with estrogen receptors, resulting in phytoestrogenic effects that are particularly relevant for hormone-dependent cancers including breast and endometrial malignancies [1]. Through selective estrogen receptor modulation, these lignans can inhibit the proliferation of estrogen-responsive tumor cells while potentially providing protective effects in normal tissues.

Molecular Targets in Cancer Pathways

The anticancer mechanisms of lignans operate at multiple levels within cellular signaling networks:

Oxidative Stress Modulation: Lignans including SDG, ED, and EL effectively prevent lipid peroxidation through concentration-dependent quenching of hydroxyl radicals, with some lignans demonstrating superior antioxidant activity compared to vitamin E [1] [7]. Schisandrin B protects renal and hepatic tissues by reducing oxidative stress and fibrosis, while sauchinone activates AMPK via LKB1 to prevent iron-induced liver damage [1].

Inflammatory Pathway Regulation: Syringaresinol activates Nrf2 signaling and suppresses NF-κB and MAPK pathways, protecting renal and cardiac tissues [1]. Honokiol exhibits neuroprotective effects in neurodegeneration models, highlighting the anti-inflammatory potential of lignans across tissue types [1].

Apoptosis Induction and Cell Cycle Control: Lignans modulate expression of Bcl-2 family proteins, caspases, and other regulators of programmed cell death, promoting elimination of malignant cells while sparing normal tissues [2] [7]. Additionally, they interfere with cell cycle progression through regulation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases.

Hormonal Pathway Modulation: As phytoestrogens, lignans compete with endogenous estrogens for receptor binding, potentially reducing the proliferative stimulus in hormone-responsive tissues and decreasing risk for breast, endometrial, and prostate cancers [1] [7].

Quantitative Analysis of Lignan Antitumor Activity

Table 2: Antitumor Mechanisms of Selected Lignans

| Lignan Compound | Molecular Targets | Cancer Types Studied | Primary Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schisandrin B | AMPK/LKB1, oxidative stress pathways | Liver, renal cancers | Reduces oxidative stress and fibrosis; protects against iron-induced damage |

| Syringaresinol | Nrf2, NF-κB, MAPK pathways | Renal, cardiac cancers | Activates Nrf2; inhibits pyroptosis; suppresses NF-κB and MAPK signaling |

| Flaxseed lignans (SDG, ED, EL) | Estrogen receptors, reactive oxygen species | Breast, prostate, colon cancers | Phytoestrogenic activity; antioxidant effects; inhibition of angiogenesis |

| Honokiol | Inflammatory mediators | Neurological cancers | Neuroprotective; reduces inflammation in neurodegeneration models |

Note: SDG = secoisolariciresinol diglucoside; ED = enterodiol; EL = enterolactone [2] [1] [7].

Figure 2: Multimodal Antitumor Mechanisms of Lignans. Lignans target multiple cancer hallmarks including oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis resistance, and hormonal pathways.

Synthetic Yeast Consortia for Lignan Biosynthesis

Innovative Bioproduction Platforms

The sustainable production of plant lignans has been significantly advanced through the development of synthetic yeast consortia engineered for de novo biosynthesis. Recent groundbreaking research has demonstrated the reconstruction of complete lignan biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a consortium approach with obligated mutualism [3] [4] [6]. This strategy effectively addresses the challenges of metabolic promiscuity and pathway complexity that have previously hampered lignan bioproduction.

The synthetic consortium utilizes two auxotrophic yeast strains (met15Δ and ade2Δ) that form a mutually dependent relationship, cross-feeding essential metabolites while dividing the biosynthetic pathway into upstream and downstream modules [6]. This multicellular division of labor mimics the spatial and temporal regulation found in plant biosynthetic systems, with ferulic acid serving as a metabolic bridge between the strains [3] [4]. The engineered system successfully overcomes the broad substrate spectrum of 4-coumarate:CoA ligase that typically leads to undesirable side reactions, thereby enhancing metabolic flux toward target lignans.

Biosynthetic Pathway Engineering

The de novo biosynthesis of lignans in yeast involves a sophisticated series of over 40 enzymatic reactions reconstructed from plant sources [6]. The upstream module converts simple carbon sources into coniferyl alcohol, the universal precursor for lignans, while the downstream module catalyzes the dirigent protein-mediated stereospecific coupling to form pinoresinol, followed by subsequent reductions and glycosylations to produce lariciresinol and its diglucoside derivatives [3] [4].

This platform has demonstrated successful production of key lignan skeletons, including pinoresinol and lariciresinol, along with complex antiviral lignans such as lariciresinol diglucoside [3] [4]. The scalability of the consortium approach has been verified, establishing a foundational engineering platform for heterologous synthesis of diverse lignans that addresses the critical supply chain challenges associated with plant extraction [3] [6].

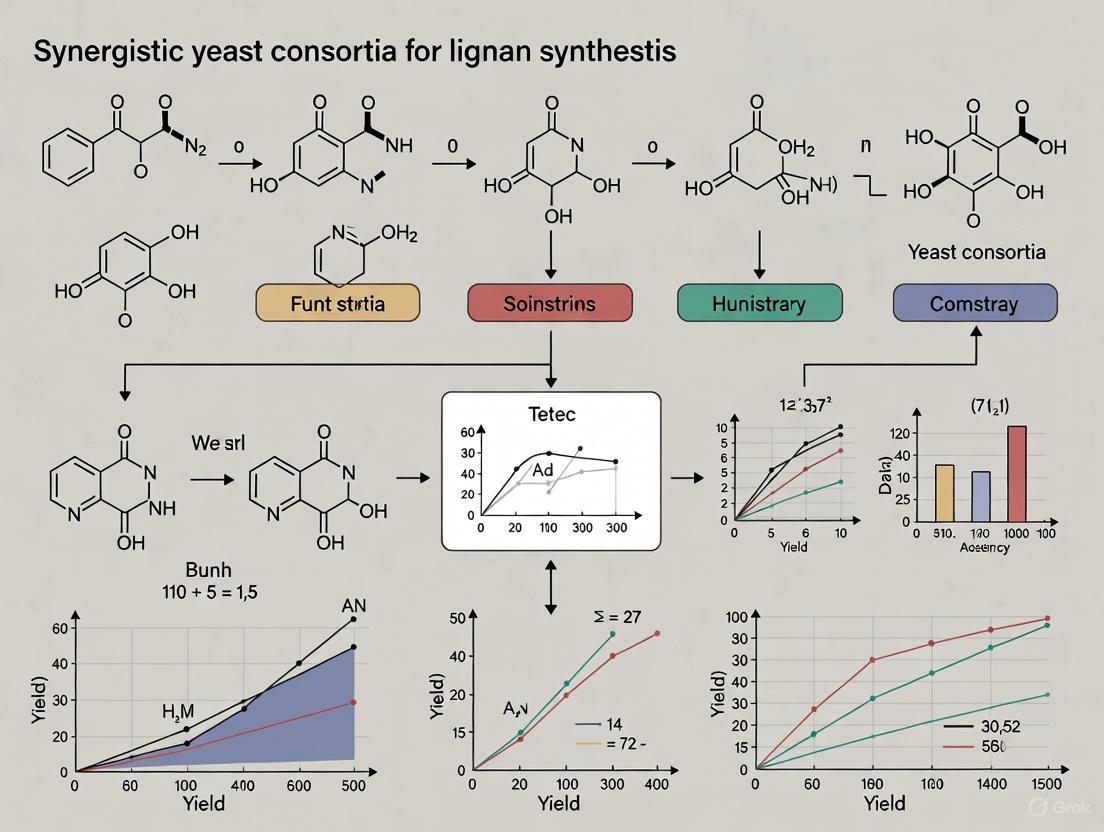

Figure 3: Synthetic Yeast Consortium for Lignan Biosynthesis. Metabolic division of labor between upstream and downstream modules enables efficient production of complex lignans.

Research Reagent Solutions for Lignan Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lignan Investigations

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHK-21 cells | ATCC passages 16-25 | Antiviral activity assays | FMDV propagation and infection models |

| FMDV serotype A | A/TAI/NP05/2017; titer 1×10ⷠTCID₅₀/mL | Antiviral mechanism studies | Well-characterized viral model system |

| Lignan compound library | 82 compounds from PSC database + 381 from ChemFaces | Virtual screening | Comprehensive structural diversity |

| AutoDock Vina | Exhaustiveness=20, max modes=9 | Molecular docking studies | Predicts ligand-protein interactions |

| CCK-8 assay kit | TargetMol | Cytotoxicity determination | Measures cell viability post-treatment |

| Auxotrophic yeast strains | met15Δ and ade2Δ S. cerevisiae | Consortium engineering | Enables obligated mutualism design |

| FMDV minigenome assay | GFP-based reporter system | 3Dpol inhibition assessment | Specific polymerase activity measurement |

Note: Specifications compiled from multiple experimental methodologies [3] [5] [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking Protocol

The identification of lignans with antiviral potential employs a structured virtual screening approach:

Protein Preparation: Retrieve the crystal structure of FMDV 3Dpol (PDB: 1wne.pdb) as a template for homology modeling of specific serotypes. Prepare the macromolecular structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining flexible residues in the active site [5].

Ligand Library Construction: Assemble a comprehensive lignan compound library from diverse sources including the Plant Secondary Compounds (PSC) database and commercial suppliers (e.g., ChemFaces). Retrieve 3D structures from PubChem and prepare for docking through energy minimization and format conversion [5].

ADME/Tox Filtering: Screen all compounds for drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties using SwissADME software to eliminate candidates with unfavorable characteristics [5].

Two-Step Docking Procedure:

- Blind Docking: Conduct initial screening with grid box covering the entire FMDV 3Dpol molecule (grid size: 65Å×70Å×65Å) to identify potential binding regions [5].

- Focused Docking: Perform refined docking targeting the substrate binding region (Motifs A-F) with specific focus on catalytic residues including Asp240, Asp245, Asp338, and Asp339 (grid size: 30Å×30Å×35Å) [5].

Analysis and Visualization: Analyze docking poses based on binding energy and interaction patterns. Visualize protein-ligand interactions using Discovery Studio Visualizer and UCSF ChimeraX to identify key binding interactions [5].

Antiviral Activity Assessment Protocol

The evaluation of lignan antiviral efficacy follows a standardized experimental workflow:

Cell Culture Maintenance: Culture BHK-21 cells (passages 16-25) in complete MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, and 1× Antibiotic-Antimycotic at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [5].

Cytotoxicity Determination:

- Seed cells at 2×10ⴠcells/well in 96-well plates and incubate overnight.

- Treat with serially diluted lignan compounds (0-100μM) for 24 hours.

- Add CCK-8 solution (10μL/well) and incubate for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Measure absorbance at 450nm and calculate cell viability percentage.

- Determine CC50 values using GraphPad Prism non-linear regression analysis [5].

Antiviral Activity Assay:

- Pre-viral Entry: Pre-treat cells with lignans for 1 hour before virus infection.

- Post-viral Entry: Infect cells with FMDV (100 TCIDâ‚…â‚€) for 1 hour, then add lignans.

- Protective Effect: Pre-treat cells with lignans, remove before infection.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours, then fix and stain for viral antigen detection.

- Quantify antiviral effects using immunoperoxidase monolayer assay [5].

Mechanism-Specific Assessment:

- Conduct FMDV minigenome assays to specifically evaluate 3Dpol inhibition.

- Measure negative-strand RNA production using RT-qPCR to confirm replication inhibition.

- Calculate EC50 values from dose-response curves [5].

Yeast Consortium Engineering Protocol

The construction of synthetic yeast consortia for lignan production involves coordinated genetic engineering:

Strain Development:

Pathway Division and Engineering:

- Divide the complete lignan biosynthetic pathway into upstream (coniferyl alcohol production) and downstream (lignan skeleton formation and modification) modules.

- Engineer upstream strain with phenylpropanoid pathway genes optimized for coniferyl alcohol production.

- Engineer downstream strain with dirigent protein, pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase, and glycosyltransferase genes [3] [4].

Consortium Establishment and Optimization:

Product Analysis and Validation:

Plant lignans represent a promising class of therapeutic compounds with demonstrated efficacy against viral pathogens and cancer cells through multifaceted mechanisms of action. The recent advancement in synthetic yeast consortia for de novo lignan biosynthesis addresses critical challenges in sustainable supply, enabling further pharmaceutical development of these valuable compounds. The integration of cutting-edge metabolic engineering with detailed mechanistic understanding of lignan bioactivity creates a powerful platform for drug discovery and development.

Future research directions should focus on expanding the repertoire of lignans accessible through microbial production, elucidating structure-activity relationships to guide therapeutic optimization, and advancing preclinical studies toward clinical applications. The synergistic combination of traditional pharmacological investigation with innovative bioproduction technologies positions plant lignans as increasingly important contributors to human health in the context of emerging viral threats and cancer challenges.

Lignans, a class of low molecular weight polyphenolic compounds, have garnered significant attention in pharmaceutical research due to their promising antitumor and antiviral properties [6] [8]. These plant-derived secondary metabolites serve crucial ecological functions, providing protection against herbivores and microorganisms while participating in plant growth regulation and lignification processes [9] [10]. From a therapeutic perspective, lignans exhibit diverse biological activities including antibacterial, antiviral, antitumor, antiplatelet, and antioxidant properties [9]. Despite their considerable therapeutic potential, the sustainable supply of lignans faces substantial challenges through both plant extraction and chemical synthesis routes [6]. These supply chain limitations have constrained lignan availability for pharmaceutical development and clinical applications, creating a critical bottleneck in leveraging their full medicinal value.

The supply chain challenges are particularly pressing given the increasing market demand for these compounds. This technical analysis examines the fundamental limitations of conventional lignan production methods and explores the emerging paradigm of synthetic yeast consortia as a transformative solution. By applying advanced metabolic engineering and synthetic biology principles, researchers are pioneering novel biosynthetic platforms that could potentially overcome longstanding barriers in lignan production.

Fundamental Limitations of Plant Extraction

Technical and Economic Constraints

The extraction of lignans from plant sources faces multiple technical and economic hurdles that limit their commercial viability. Plant lignans typically exist in complex polymeric forms or as glycosides conjugated with other phenolic compounds, necessitating sophisticated extraction and purification protocols [11]. Table 1 summarizes the primary limitations associated with plant extraction of lignans.

Table 1: Technical and Economic Constraints of Plant Extraction

| Constraint Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Supply Chain |

|---|---|---|

| Source Availability | Low abundance in plants (often <1% dry weight) [12] | Requires processing large volumes of plant material |

| Content influenced by species, genetics, and environmental conditions [12] | Inconsistent raw material quality and quantity | |

| Extraction Complexity | Presence in complex macromolecular structures [11] | Requires multiple extraction and hydrolysis steps |

| Co-occurrence with similar compounds [11] | Challenges in isolation and purification | |

| Technical Challenges | Need for specialized extraction techniques [11] | Increased equipment and processing costs |

| Sensitivity to processing conditions [11] | Potential degradation during extraction |

The inherent complexity of lignan structures within plant matrices presents significant extraction challenges. For instance, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) in flaxseed exists as an oligomer where five SDG units are interconnected via 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid (HMGA) residues in a straight-chain structure [12]. This complex molecular architecture necessitates specialized extraction approaches, including acidic, alkaline, or enzymatic hydrolysis to liberate the desired lignans [11]. These additional processing steps increase production costs, introduce potential degradation pathways, and reduce overall yields.

Methodological Considerations in Lignan Extraction

Advanced extraction techniques have been developed to optimize lignan recovery from plant material. The selection of appropriate methods depends on the specific plant matrix, target lignans, and desired purity levels:

Sample Preparation: Proper handling of plant material is crucial for lignan stability. Methods include air-drying, oven-drying (up to 60°C), and freeze-drying [11]. Thermal processing requires careful optimization as temperatures above 100°C can degrade some lignans, while others remain stable up to 200°C [11].

Extraction Techniques: Modern approaches include deep eutectic solvents, dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction, dispersive micro solid-phase extraction, hollow-fiber liquid-phase microextraction, and supramolecular solvents [13]. These methods aim to improve selectivity and efficiency while reducing environmental impact.

Stability Considerations: Lignans exhibit varying stability profiles based on their structure and environment. Photostability concerns necessitate protection from light during processing, as demonstrated by the oxidation of 7-hydroxymatairesinol to various products under irradiation [11].

Despite these methodological advances, the fundamental economic and technical constraints of plant-based extraction remain significant barriers to sustainable lignan supply chains.

Challenges in Chemical Synthesis

Structural Complexity and Synthetic Efficiency

The chemical synthesis of lignans presents formidable challenges due to their complex molecular architectures featuring multiple chiral centers and diverse ring systems [9]. Table 2 outlines the primary synthetic challenges for different lignan subclasses.

Table 2: Synthetic Challenges in Lignan Production

| Lignan Subclass | Key Structural Features | Major Synthetic Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Acyclic Lignans | Dibenzyl tetrahydrofuran, dibenzylbutyrolactone skeletons [9] | Stereoselective formation of multiple chiral centers |

| Dibenzocyclooctadienes | Complex eight-membered rings with axial chirality [9] | Control of atropisomerism and ring strain management |

| Arylnaphthalenes | Planar naphthalene cores with lactone bridges [9] | Regioselective cyclization and oxidation state control |

| Furofurans | Complex tetracyclic frameworks with multiple stereocenters [9] | Simultaneous control of configuration at contiguous stereocenters |

The synthetic complexity is exemplified by approaches to compounds such as (+)-galbelgin, which requires a stereoselective aza-Claisen rearrangement and careful establishment of four adjacent stereocenters [9]. Similarly, the synthesis of gymnothelignan N involves constructing a challenging seven-membered ring skeleton via an oxidative Friedel-Crafts reaction using phenyliodonium diacetate (PIDA) as the oxidant [9]. These multi-step sequences often result in low overall yields, limiting their practical application for large-scale production.

Methodological Approaches and Limitations

Various innovative synthetic strategies have been developed to address the structural challenges of lignans:

Photochemical Methods: The [2+2] photodimerization approach has been employed for synthesizing (±)-tanegool and (±)-pinoresinol, followed by oxidative ring-opening steps [9]. While elegant, photochemical methods present scalability challenges for industrial application.

Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis: Enantioselective approaches using combined photoredox and enamine catalysis have enabled the asymmetric synthesis of complex lignans like (−)-bursehernin [9]. These methods provide excellent enantioselectivity but often require specialized catalysts and conditions.

Transition Metal-Catalyzed Reactions: Ni-catalyzed cyclization/cross-coupling strategies have been applied for synthesizing (±)-kusunokinin, (±)-dimethylmetairesinol, and related compounds [9]. Such methods improve efficiency but still involve multiple steps and purification operations.

Despite these sophisticated methodological developments, the economic viability of chemical synthesis remains limited by the number of steps, yields, and specialized requirements for producing complex lignan structures at commercial scales.

Synthetic Yeast Consortia: A Paradigm Shift

Conceptual Framework and Design Principles

The emerging approach of synthetic yeast consortia represents a transformative strategy for overcoming the supply chain challenges associated with traditional lignan production methods. This innovative paradigm involves engineering microbial communities with division-of-labor principles to achieve complex biosynthetic tasks [14] [3]. The fundamental concept involves distributing the extensive lignan biosynthetic pathway across specialized yeast strains that engage in obligated mutualism through metabolic cross-feeding [6] [8].

The synthetic consortium developed by Zhou and colleagues exemplifies this approach, utilizing two auxotrophic Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains (met15Δ and ade2Δ) that form a mutually dependent relationship [3] [8]. These strains cross-feed essential metabolites while dividing the lignan biosynthetic pathway into upstream and downstream modules, enabling the de novo synthesis of lariciresinol diglucoside through a remarkable series of over 40 enzymatic reactions [6]. This compartmentalization strategy effectively addresses the challenge of metabolic promiscuity that often plagues attempts to reconstruct complex plant pathways in single microbial hosts.

Diagram 1: Three production paradigms for lignan synthesis. The synthetic yeast consortium approach addresses key limitations of plant extraction and chemical synthesis.

Implementation and Experimental Validation

The experimental implementation of synthetic yeast consortia for lignan production involves sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies:

Consortium Construction: Researchers designed two auxotrophic yeast strains with complementary metabolic deficiencies. The met15Δ strain requires methionine, while the ade2Δ strain requires adenine for survival [8]. This genetic design creates an obligate mutualism where neither strain can proliferate without cross-feeding from the partner strain.

Pathway Division: The extensive lignan biosynthetic pathway was divided into upstream and downstream modules distributed between the two strains. The upstream module specializes in converting simple carbon sources to pathway intermediates, while the downstream module processes these intermediates into final lignan products [3].

Metabolic Bridge Implementation: Ferulic acid serves as a key metabolic bridge between the consortium members, facilitating the efficient transfer of intermediates while minimizing metabolic cross-talk and promiscuity [3].

This innovative approach successfully achieved the de novo biosynthesis of key lignan skeletons, including pinoresinol and lariciresinol, and demonstrated scalability by producing complex antiviral lignans such as lariciresinol diglucoside [3]. The consortium platform effectively overcame the challenges of metabolic promiscuity that typically hamper efficient flux through complex biosynthetic pathways in single-strain systems.

Experimental Protocols for Yeast Consortium Engineering

Strain Construction and Pathway Engineering

The development of synthetic yeast consortia for lignan biosynthesis requires meticulous experimental protocols at the intersection of metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and microbial ecology. The following methodology outlines the key procedures for constructing and optimizing these systems:

Auxotrophic Strain Development:

- Select appropriate auxotrophic markers (e.g., met15Δ, ade2Δ) to create obligate mutualism [8].

- Employ CRISPR-Cas9 or conventional gene knockout techniques to delete essential genes in amino acid or nucleotide biosynthesis pathways.

- Verify auxotrophy phenotypes through selective plating on minimal media with and without supplemented metabolites.

Pathway Splitting and Optimization:

- Identify natural metabolic choke points or create synthetic branch points for pathway division.

- Distribute upstream pathway enzymes (from primary metabolism to key intermediates like coniferyl alcohol) to one strain.

- Allocate downstream pathway enzymes (from intermediates to final lignan products) to the partner strain.

- Optimize codon usage and gene expression levels using synthetic promoters and terminators.

Cross-Feeding Validation:

- Co-culture auxotrophic strains in minimal media to verify mutualistic growth.

- Monitor population dynamics using flow cytometry with strain-specific fluorescent markers.

- Quantify metabolic exchange rates using LC-MS/MS analysis of cross-fed metabolites.

Consortium Stabilization and Scale-Up

Maintaining stable consortium composition and function represents a critical challenge in synthetic ecology. The following protocols address stabilization and production scaling:

Dynamic Control Implementation:

- Engineer metabolite biosensors to monitor pathway intermediate levels.

- Implement feedback regulation circuits to balance pathway flux between strains.

- Use quorum sensing systems to coordinate gene expression across the consortium.

Fermentation Optimization:

- Determine optimal initial inoculation ratios through systematic co-culture screening.

- Develop fed-batch strategies to maintain metabolic harmony during scale-up.

- Monitor and control dissolved oxygen, pH, and nutrient feeding to support both strains.

Production and Analytics:

- Implement in situ product extraction methods to alleviate product toxicity.

- Use advanced mass spectrometry techniques for comprehensive lignan profiling.

- Apply ({}^{13})C metabolic flux analysis to quantify pathway activity distribution between strains.

The successful implementation of these protocols has enabled the de novo biosynthesis of plant lignans, demonstrating the viability of synthetic yeast consortia as a solution to longstanding supply chain challenges [3] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The engineering of synthetic yeast consortia for lignan production requires specialized reagents and genetic tools. Table 3 catalogues essential research reagents and their applications in developing these advanced biocatalytic systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Engineering Synthetic Yeast Consortia

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains | met15Δ, ade2Δ S. cerevisiae strains [8] | Creating obligate mutualism through metabolic interdependency |

| Pathway Enzymes | Plant-derived cytochrome P450s, dirigent proteins, UDP-glycosyltransferases [3] | Reconstituting plant lignan biosynthetic pathways in yeast |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 components, yeast integrative plasmids, synthetic promoters [15] | Genome engineering and heterologous gene expression |

| Analytical Standards | Pinoresinol, lariciresinol, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside [11] | Quantifying pathway intermediates and final products |

| Culture Components | Synthetic complete dropout media, amino acid supplements [15] | Maintaining selective pressure for consortium stability |

| Emapticap pegol | Emapticap pegol, CAS:1390628-22-4, MF:C18H37N2O10P, MW:472.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cefetamet-d3 | Cefetamet-d3, MF:C14H15N5O5S2, MW:400.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic application of these research reagents enables the design, construction, and optimization of synthetic yeast consortia capable of overcoming the fundamental limitations of traditional lignan production methods. The auxotrophic strains form the foundation of the obligate mutualism, while the plant-derived enzymes facilitate the reconstitution of complex lignan biosynthetic pathways. Advanced genetic tools allow precise control of gene expression, and specialized analytical methods enable rigorous quantification of consortium performance and output.

The supply chain challenges associated with lignan production through plant extraction and chemical synthesis have historically constrained the therapeutic application of these valuable compounds. Plant extraction faces fundamental limitations in yield, consistency, and purification complexity, while chemical synthesis struggles with the structural complexity and stereochemical demands of lignan architectures. The emerging paradigm of synthetic yeast consortia represents a transformative approach that leverages principles of synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and microbial ecology to overcome these longstanding barriers. By distributing biosynthetic pathways across specialized microbial strains engaged in obligate mutualism, this innovative platform achieves efficient de novo production of complex lignans while avoiding the pitfalls of metabolic promiscuity that plague single-strain approaches. As these synthetic consortia platforms mature, they hold significant promise for establishing sustainable, scalable supply chains to meet the growing pharmaceutical demand for lignans and other complex plant-derived therapeutics.

The Promise and Hurdles of Single-Strain Microbial Factories

The pursuit of sustainable and reliable sources for complex plant natural products has positioned microbial manufacturing as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology. For years, the primary strategy has centered on developing single-strain microbial factories—engineered microorganisms, typically yeast or E. coli, reprogrammed to produce high-value compounds. This approach has seen notable successes, exemplified by the semi-synthetic production of the antimalarial artemisinin [16]. However, the reconstruction of intricate plant biosynthetic pathways, such as those for lignans with their complex structures and diverse stereochemistry, has exposed significant biological and engineering challenges inherent to the single-strain paradigm. These hurdles include metabolic burden, enzyme promiscuity, and cofactor imbalance, which often limit titers and process efficiency [16]. Within this context, the emergence of synthetic yeast consortia represents a transformative evolution in the field. This whitepaper explores the limitations of single-strain factories for lignan synthesis and examines how multicellular consortium-based approaches, inspired by natural metabolic division of labor, are paving the way for a new generation of microbial manufacturing.

The Single-Strain Paradigm: Engineering Challenges and Established Strategies

The construction of a single-strain microbial factory is a monumental feat of metabolic engineering, requiring the orchestration of numerous heterologous enzymes into a functional, efficient pathway. This process is fraught with technical hurdles.

Core Engineering Hurdles

- Metabolic Burden and Resource Competition: The extensive genetic engineering required to introduce long biosynthetic pathways places a significant drain on the host's cellular resources. This can impair native processes like growth and maintenance, ultimately reducing the flux toward the desired product [16].

- Enzyme Promiscuity and Metabolic Crosstalk: Heterologous plant enzymes often exhibit imperfect specificity, leading to the unintended conversion of intermediates into off-target byproducts. This "hijacking" of intermediates severely diminishes the yield of the final product. In lignan pathways, this can result in the loss of key skeletons like pinoresinol and lariciresinol [3].

- Cofactor Imbalance: Many critical plant enzymes, including Cytochromes P450 and dehydrogenases, depend on cofactors like NADPH. High demand for these cofactors can exhaust the cell's supply, creating a bottleneck that limits the overall throughput of the pathway [16].

Established Engineering Solutions

Researchers have developed a sophisticated toolkit to address these challenges within a single strain, as demonstrated in efforts to produce lignan precursors.

Table 1: Key Engineering Strategies for Single-Strain Microbial Factories

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Amplification | Controlling gene expression levels with strong promoters and optimized codons; increasing gene copy number for bottleneck enzymes [16]. | Used in vindoline production to alleviate bottlenecks and reduce by-product formation [16]. |

| Host Metabolism Rewiring | Knocking out competing pathways (e.g., Ehrlich pathway for alkaloids); expressing feedback-insensitive enzymes (e.g., HMG-CoA reductase) [16]. | Applied in tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid production to prevent diversion of precursors [16]. |

| Spatial Reconfiguration | Compartmentalizing pathways in organelles like peroxisomes or enlarging the endoplasmic reticulum to enhance substrate channeling and reduce cytotoxicity [16]. | Improved monoterpene production by housing the mevalonate pathway in peroxisomes [16]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration | Overexpressing NADPH-regenerating enzymes (e.g., ZWF1, POS5) or pulling flux through the pentose phosphate pathway [16]. | Boosted CaA and FA (podophyllotoxin precursors) synthesis by over 45%, to >360 mg/L, via phosphoketolase (Xfpk) expression [16]. |

The following diagram illustrates how these strategies are integrated to optimize a single-strain factory, highlighting the complex engineering required to overcome inherent limitations.

A Case Study in Complexity: The Challenge of Lignan Synthesis

Lignans, a class of phytoestrogens with demonstrated antiviral and anticancer properties, exemplify the difficulties of reconstructing plant pathways in a single microbe. Their biosynthesis from simple sugars involves multiple steps, including the formation of the precursor coniferyl alcohol and its subsequent coupling to form key skeletons like pinoresinol [3] [17]. A major hurdle is metabolic promiscuity, where intermediates are diverted to unwanted side products, severely crippling the efficiency of the pathway [3]. This complexity has made the heterologous production of lignans, particularly the more valuable lignan glycosides, a persistent challenge.

Different microbial hosts present distinct advantages and limitations. Research has advanced in both Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Table 2: Microbial Production of Lignans and Precursors in Single Strains

| Product | Host | Engineering Strategy | Reported Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic Acid (CaA) | S. cerevisiae | Rewired shikimate pathway; optimized NADPH regeneration via pentose phosphate pathway. | >360 mg/L | [16] |

| (+)-Pinoresinol | E. coli | Co-expression of peroxidase (Prx02) and vanillyl alcohol oxidase (PsVAO) in a single strain. | 698.9 mg/L | [17] |

| Lignan Glycosides | E. coli | "One-cell, one-pot" fermentation with multiple heterologous enzymes, including UGTs for glycosylation. | 1.71 mg/L (Pinoresinol glucoside) | [17] |

The "one-cell, one-pot" approach in E. coli, while successfully producing a range of lignan glycosides, resulted in notably lower yields for the glycosylated products compared to earlier pathway steps [17]. This drop in efficiency underscores the significant burden that long, complex pathways place on a single host, necessitating a paradigm shift in how these systems are designed.

The Consortium Approach: Overcoming Hurdles through Division of Labor

In a radical departure from the single-strain model, synthetic biology is increasingly turning to microbial consortia. This approach distributes different segments of a biosynthetic pathway across multiple, specialized microbial strains, mimicking the natural division of labor found in multicellular organisms or complex microbial communities [3] [18].

A landmark 2025 study demonstrated the power of this approach for lignan synthesis. Researchers constructed a synthetic yeast consortium with obligate mutualism, where auxotrophic yeast strains (each unable to produce an essential metabolite) were forced to cooperate for survival [3] [14]. The lignan biosynthetic pathway was strategically divided among these strains, using ferulic acid as a metabolic bridge to connect their metabolisms. This architecture successfully overcame the issue of metabolic promiscuity that plagues single-strain factories [3].

The consortium achieved the de novo synthesis of key lignan skeletons, pinoresinol and lariciresinol, from simple carbon sources. Furthermore, by combining this system with systematic engineering, the researchers scaled the production to synthesize complex antiviral lignans, including lariciresinol diglucoside [3]. This work provides a compelling engineering platform for the heterologous synthesis of lignans and illustrates the promise of multicellular strategies for complex natural products.

The following diagram contrasts the linear, centralized metabolism of a single-strain factory with the distributed, modular metabolism of a synthetic consortium.

Experimental Framework: From Single Strain to Consortium

This section outlines the core methodologies for constructing and evaluating both single-strain and consortium-based microbial factories for lignan production.

Protocol for Single-Strain Factory Engineering

A typical workflow for constructing a lignan-producing E. coli or yeast strain involves several key stages [17]:

- Pathway Identification and Gene Selection: Identify plant genes encoding enzymes in the target pathway (e.g., dirigent proteins, pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase (PLR), secoisolariciresinol dehydrogenase (SIRD), glycosyltransferases (UGTs)).

- Codon Optimization and Vector Construction: Synthesize codon-optimized genes for the microbial host. Clone them into expression vectors (e.g., pET-Duet, pCDF-Duet for E. coli) under inducible promoters.

- Host Transformation and Strain Validation: Transform the constructed plasmids into the microbial host. Validate enzyme expression via SDS-PAGE and enzymatic assays.

- Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis:

- Inoculate engineered strain in a defined medium, often with a fed-batch system for high density.

- For "one-pot" reactions, a substrate like eugenol may be added at induction.

- Monitor cell growth and periodically sample the broth.

- Analyze samples using HPLC or LC-MS to quantify intermediate and final product concentrations.

Protocol for Consortium Assembly and Analysis

The construction of a synthetic consortium for lignan synthesis, as reported by Chen et al., involves creating interdependence between strains [3]:

- Consortium Design and Pathway Splitting: Strategically divide the biosynthetic pathway into modules. A critical decision is identifying a suitable metabolic bridge (e.g., ferulic acid) to connect the strains.

- Strain Engineering and Auxotrophy Induction: Engineer each module into separate yeast strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae). Create obligate mutualism by introducing complementary auxotrophies (e.g., different amino acid requirements) into each strain to force co-dependence.

- Co-cultivation under Selective Conditions: Co-culture the auxotrophic strains in a minimal medium that requires both strains to grow. This ensures stable coexistence and cooperative bioproduction.

- System Performance Evaluation: Measure the titer of the final lignan product (e.g., lariciresinol diglucoside). Assess the stability of the consortium by monitoring the population ratio over multiple generations. Scale up fermentation to demonstrate industrial relevance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Lignan Pathway Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Lignan Synthesis

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET-Duet, pCDF-Duet vectors | Allow for simultaneous expression of multiple enzymes in a single host, crucial for long pathways [17]. |

| Key Lignan Biosynthesis Enzymes | Dirigent protein (DIR), Pinoresinol/Lariciresinol Reductase (PLR), Secoisolariciresinol Dehydrogenase (SIRD) | Catalyze the specific steps from coniferyl alcohol to secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol [17]. |

| Glycosylation Tools | UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGT71B5, UGT74S1), UDPG synthesis module | Mediate the transfer of sugar moieties to lignan aglycones, producing the more bioactive glycosylated forms [17]. |

| Cofactor Engineering Enzymes | Phosphoketolase (Xfpk), Transaldolase (Tald) | Pull flux through the pentose phosphate pathway to regenerate NADPH, a critical cofactor for P450s [16]. |

| Analytical Standards | (+)-Pinoresinol, (-)-secoisolariciresinol, (-)-matairesinol, and their glucosides | Essential for developing HPLC/LC-MS methods to identify and quantify products in microbial broths [17]. |

| UR-3216 | UR-3216, MF:C27H29N7O7, MW:563.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Axareotide | Axareotide, CAS:2126833-17-6, MF:C54H68ClN11O12S2, MW:1162.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey of microbial manufacturing is one of constant evolution. Single-strain microbial factories represent a monumental achievement in metabolic engineering, yet their inherent biological constraints create a ceiling for the production of highly complex molecules like lignans. The systematic engineering of these strains—through pathway amplification, cofactor balancing, and spatial reconfiguration—has pushed this ceiling higher. However, the challenges of metabolic burden, promiscuity, and toxicity remain significant hurdles. The emergence of synthetic yeast consortia marks a pivotal shift, moving from a paradigm of centralization to one of distributed responsibility. By dividing labor among cooperating, specialized strains, this approach effectively bypasses many of the limitations intrinsic to single cells. The successful application of this strategy for the de novo biosynthesis of plant lignans, including antiviral glycosides, offers a robust and scalable platform [3]. As the field advances, the future of microbial manufacturing likely lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the precision of single-strain engineering with the power and resilience of synthetic microbial ecosystems, ultimately securing a sustainable supply of vital plant-based therapeutics.

Syntrophy, a form of obligatory mutualism where microorganisms survive by feeding off the metabolic products of each other, represents a fundamental ecological interaction that underpins the stability and function of diverse microbial communities [19]. In natural environments, the overwhelming majority of microbial species exist as participants of interspecies and intraspecies communities where members occupy specific metabolic niches [19]. These cooperative networks confer adaptive advantages including extended metabolic capabilities, increased adaptation potential to fluctuating environments, enhanced stress resistance, and more efficient metabolic resourcing in challenging growth conditions [19]. The close proximity of microbes changes the extracellular metabolite environment and facilitates exchange of metabolites between cells, creating cross-feeding arrangements where the exometabolome of each strain supplies the metabolites required by its neighbor [19].

In recent years, synthetic biology has leveraged these natural principles to engineer synthetic microbial consortia with enhanced bioprocessing capabilities [20] [21]. These constructed communities apply engineering principles to biological system design, creating artificial consortium systems by co-cultivating two or more microorganisms under certain environmental conditions [20]. Synthetic microbial consortia tend to have high biological processing efficiencies because the division of labor reduces the metabolic burden of individual members, making them particularly valuable for complex biosynthetic tasks [20]. Engineered microbial consortia often demonstrate enhanced system performance and robustness compared with single-strain biomanufacturing production platforms, especially for the production of complex natural products with pharmaceutical relevance [3] [21].

Quantitative Foundations of Microbial Syntrophy

Key Metrics and Performance Indicators

The establishment of stable syntrophic relationships depends on several quantifiable parameters that govern population dynamics and functional output. Systematic studies have identified critical factors that influence the stability and productivity of engineered consortia.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Syntrophic Community Dynamics

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Impact on Community Dynamics | Experimental Tuning Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Exchange | Metabolite production rate (φ) | Nonlinear relationship with growth; peak production at φ = 0.5 [21] | 0-100% of glucose flux |

| Population Initialization | Initial population ratio | Determines final population composition; sensitivity index ~0.15 [21] | Viable across multiple orders of magnitude |

| Nutrient Environment | Extracellular metabolite supplementation | Affects batch culture time; sensitivity index ~0.05 [21] | Species-dependent minimum concentrations |

| System Scale | Initial cell density | Influences timing and establishment of cross-feeding [21] | 10^3-10^8 cells/mL |

| Growth Characteristics | Strain-specific growth rates | Primary determinant of individual strain growth rates [21] | Varies by auxotrophic strain |

Global sensitivity analysis of two-member consortia has revealed that final population size is most sensitive to metabolite exchange parameters (φi) but relatively insensitive to other experimentally tractable dials such as metabolite supplementation and initial population ratios [21]. Batch culture times are most sensitive to glucose accumulation parameters, with metabolite exchange being the next most significant factor [21]. Final population composition demonstrates sensitivity to tractable parameters including initial population ratio and the metabolite exchange rates [21].

Experimentally Documented Syntrophic Pairs

High-throughput phenotypic screening of pairwise combinations of auxotrophic Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion mutants has identified specific pairs capable of spontaneous syntrophic growth [19]. From 1,891 cocultures tested, 49 pairwise combinations (2.6%) formed by 36 unique deletion mutants demonstrated substantial synergistic growth compared to individual auxotrophs [19].

Table 2: Documented Syntrophic Auxotrophic Pairs in S. cerevisiae

| Auxotrophic Pair | Pathway Involvement | Growth Advantage | Stability Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| trp2Δ-trp4Δ | Tryptophan biosynthesis | High, exchanges intermediate anthranilate [19] | Stable over multiple subcultures |

| lysine-adenine pair | Amino acid/nucleotide synthesis | Demonstrated stable syntrophy [21] | Maintained population equilibrium |

| leucine-tryptophan pair | Amino acid synthesis | Viable co-culture formation [21] | Sustainable co-dependence |

| Various amino acid auxotrophs | Methionine, histidine, arginine pathways | 47/49 successful pairs involved amino acid/nucleotide pathways [19] | Pathway-dependent stability |

The majority (96%) of successful cocultures contained at least one strain with a deleted gene having known functional association to amino acid or nucleotide biosynthesis [19]. Seventy-five percent (27/36) of the unique gene deletions encoded enzymes that directly participate in these essential pathways [19]. Among the most frequently represented pathways were methionine and organic sulfur cycle, histidine, tryptophan, arginine, adenine, lysine, uracil, isoleucine/valine, and the aromatic amino acid superpathway [19].

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Syntrophic Communities

High-Throughput Screening for Spontaneous Syntrophy

The identification of naturally occurring syntrophic pairs requires systematic screening approaches. The following protocol has been successfully applied to identify spontaneous syntrophic communities from auxotrophic yeast mutants [19]:

Strain Library Preparation: Utilize a comprehensive gene-deletion library such as the S. cerevisiae knockout (YKO) collection comprising approximately 5,185 knockout mutants. Maintain strains in nutrient-supplemented synthetic complete (SC) media to complement inherent auxotrophies.

Auxotroph Identification: Screen individual mutants in synthetic minimal (SM) media lacking amino acid and nucleotide supplements. Identify auxotrophic strains showing poor growth (defined as <20% of parental strain optical density at 600 nm after 18 hours) in SM but robust growth in SC media.

Automated Coculture Assembly: Using automated colony-picking and liquid-handling robots, inoculate each auxotroph with every other identified auxotroph in liquid SM media in a high-throughput manner. Include appropriate monoculture controls.

Growth Assessment and Quality Control: Measure cell density (OD600) in each well after 48 hours of incubation. Apply quality control filters to exclude samples showing inconsistent growth patterns and possible contamination.

Synergistic Growth Detection: Identify syntrophic pairs by combining a Z-factor metric with growth advantage analysis. Apply statistical tests including Welch's t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing. Calculate fold difference in OD600 relative to the auxotroph with higher growth among the pair in SM.

Validation and Characterization: Reconstruct identified pairs by introducing deletions de novo in parental strains via homologous recombination to exclude artifacts from secondary mutations. Characterize stability and growth dynamics over consecutive subcultures.

This approach successfully identified 49 coculture pairs from 36 unique gene deletions that demonstrated spontaneous syntrophic growth, with most involving amino acid or nucleotide biosynthesis pathways [19].

Engineering Obligate Mutualism for Pathway Division

For complex biomanufacturing tasks such as lignan biosynthesis, engineered obligate mutualism provides a robust framework for distributing metabolic burden. The following protocol details the establishment of such systems [3]:

Strain Engineering: Create complementary auxotrophic strains by deleting genes involved in essential amino acid or nucleotide biosynthesis. Alternatively, utilize existing auxotrophic pairs from screening efforts with demonstrated stable syntrophy.

Pathway Segmentation: Divide the target biosynthetic pathway (e.g., lignan biosynthesis) at strategic points to minimize intermediate toxicity, promiscuous branching, and metabolic burden. Prefer division points where intermediates can be efficiently transported between cells.

Bridge Metabolite Identification: Identify or engineer a metabolic bridge that facilitates obligate mutualism. For lignan biosynthesis, ferulic acid has served effectively as this bridge [3].

Module Implementation: Introduce distinct pathway segments into complementary auxotrophic hosts. Optimize expression levels of heterologous enzymes using appropriate promoters and gene dosage to balance flux between consortium members.

Consortium Establishment and Optimization: Co-culture engineered strains in minimal media without nutrient supplementation to enforce mutualism. Systematically optimize initial inoculation ratios, media composition, and cultivation conditions to maximize target compound production while maintaining population stability.

Scale-Up Validation: Demonstrate scalability of the consortium using bioreactor systems, monitoring population dynamics and productivity over extended cultivation periods.

This approach has enabled the de novo synthesis of key lignan skeletons, including pinoresinol and lariciresinol, with verification of scalability for producing complex lignans such as antiviral lariciresinol diglucoside [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Constructing Synthetic Microbial Consortia

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains | S. cerevisiae trp2Δ, trp4Δ, lysine, adenine, leucine auxotrophs [19] [21] | Foundation for establishing cross-feeding | Deletions in essential biosynthesis pathways |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, homologous recombination cassettes [19] | Creating de novo deletions and pathway engineering | Enables precise genome modifications |

| Fluorescent Markers | FRAME-tags, GFP, YFP, RFP variants [22] | Tracking population dynamics in consortia | Distinguishable emission spectra |

| Culture Media | Synthetic Minimal (SM), Synthetic Complete (SC) [19] | Selection and maintenance of syntrophic communities | Defined composition essential for auxotrophs |

| Analytical Tools | Flow cytometry, HPLC-MS, spectrophotometry [22] | Monitoring population ratios and metabolite production | Enables real-time community analysis |

| Metabolic Pathway Parts | Heterologous enzymes for lignan biosynthesis [3] | Implementing divided biosynthesis pathways | Plant-origin enzymes for specialized metabolism |

| Simedeutirom | Simedeutirom, CAS:2403721-24-2, MF:C18H12Cl2N6O4, MW:450.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mavacamten-d7 | Mavacamten-d7, MF:C15H19N3O2, MW:280.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling and Regulatory Pathways in Syntrophic Systems

Syntrophic relationships are maintained through complex signaling and regulatory mechanisms that coordinate metabolic activity between partner organisms. In engineered yeast consortia, these relationships are established through fundamental biochemical principles.

Diagram 1: Fundamental Syntrophic Exchange Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the core metabolic interactions in a two-member syntrophic consortium, where mutual dependence is established through exchange of essential metabolites.

The establishment of syntrophy in microbial systems often involves complex signaling cascades that regulate metabolic interactions. In lignan-producing systems, these regulatory networks can involve hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) signaling, nitric oxide (NO) generation, and cytosolic calcium (Ca²âº) fluxes [23].

Diagram 2: Signaling Network Regulating Lignan Biosynthesis. This diagram shows the complex signaling cascade involving polyamine oxidation that regulates lignan production in microbial and plant systems, demonstrating how metabolic pathways are controlled in syntrophic communities.

Applications in Lignan Synthesis and Natural Product Production

The division of complex biosynthetic pathways across synthetic yeast consortia has emerged as a powerful strategy for producing valuable plant natural products. Lignans, with their complex structures and pharmaceutical relevance, present particular challenges for heterologous production [3]. Reconstruction of their complete biosynthesis in single yeast strains often results in metabolic promiscuity and pathway inefficiencies [3]. However, splitting the lignan biosynthetic pathway across a synthetic yeast consortium with obligated mutualism successfully overcomes these limitations [3].

In practice, researchers have employed ferulic acid as a metabolic bridge in cooperative yeast systems to facilitate the de novo synthesis of key lignan skeletons [3]. This approach mimics the natural division of metabolic labor observed in plant multicellular systems, where different cell types specialize in specific pathway segments [3]. Combined with systematic engineering strategies, this consortium approach has enabled the production of pinoresinol and lariciresinol, with verification of scalability for synthesizing complex lignans including antiviral lariciresinol diglucoside [3].

The initial proof-of-concept for this approach was established through the identification of spontaneously forming syntrophic communities in S. cerevisiae auxotrophs [19]. Characterization of these communities revealed that some pairs, such as trp2Δ and trp4Δ auxotrophs, cooperate by exchanging pathway intermediates rather than end products [19]. This fundamental discovery provided the foundation for engineering more complex systems where entire biosynthetic pathways are divided between interdependent microbial partners.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia based on natural syntrophic principles represents a paradigm shift in biotechnological production. As our understanding of microbial interactions deepens, the design of increasingly complex and stable communities becomes feasible. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing the robustness of these systems through evolutionary approaches, improving metabolite transport efficiency between consortium members, and developing more sophisticated models for predicting community dynamics.

The application of these approaches to lignan synthesis demonstrates the potential for addressing longstanding challenges in natural product manufacturing. By learning from and implementing the foundations of syntrophy observed in natural microbial communities, researchers can create next-generation bioproduction platforms that surpass the capabilities of single-strain systems. This framework not only advances biomanufacturing but also provides insights into fundamental ecological principles governing microbial interactions in natural environments.

The heterologous production of complex natural products in microbial hosts presents a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering: metabolic burden. Introducing extensive heterologous pathways into a single microbial population often overwhelms cellular resources, diverting energy and precursors from essential growth functions and ultimately limiting overall productivity [24]. This burden is particularly pronounced for intricate plant-derived compounds with multi-step biosynthesis, such as lignans, which possess valuable pharmaceutical properties but are notoriously difficult to produce efficiently in conventional single-strain systems [25].

Metabolic Division of Labor (DOL) has emerged as a powerful synthetic biology paradigm to overcome these limitations. Inspired by natural systems where distinct cell types or organisms perform complementary metabolic tasks, DOL involves distributing different steps of a biosynthetic pathway across multiple, specialized microbial populations [24]. This strategy reduces the genetic and enzymatic complexity that any single host must maintain, potentially lowering the individual burden on each population and increasing the overall system's capacity for target compound production [24] [3]. This whitepaper explores the theoretical foundation of DOL, its application in engineered yeast consortia for lignan synthesis, and the practical methodologies for implementing this advanced bioengineering framework.

Theoretical Foundation: When Does Division of Labor Benefit a System?

The core premise of DOL is the trade-off between reducing metabolic burden and maintaining pathway efficiency. While partitioning a pathway can lessen the load on each constituent population, it introduces new physical challenges, notably the transport barrier for intermediate metabolites that must traverse cell membranes and diffuse through the extracellular environment [24]. Consequently, DOL is not universally advantageous; its benefit depends on specific system parameters.

Quantitative Criteria for Implementing DOL

Mathematical modeling of common metabolic pathway architectures has established general criteria for when DOL outperforms a single population. The key parameters, summarized in the table below, include the burden imposed by enzyme expression and the kinetics of intermediate transport and turnover [24].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Metabolic Division of Labor Models

| Parameter | Description | Impact on DOL Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden (β, γ) | Load on host from heterologous enzyme expression [24]. | Higher burden favors DOL, as splitting the pathway reduces load per cell. |

| Transport Rate Constant (η) | Rate of intermediate metabolite diffusion across cell membranes [24]. | A higher rate favors DOL by reducing inefficiency from transport barriers. |

| Intermediate Turnover (δme) | Dilution or degradation rate of the extracellular intermediate [24]. | A lower rate favors DOL by ensuring intermediate availability for the second population. |

| Growth Effects (G) | Impact of metabolites on host growth (e.g., toxicity or benefit) [24]. | Toxic intermediates favor DOL by isolating their production. |

The conceptual relationship between these parameters can be visualized in the following decision pathway, which outlines the core trade-off and subsequent engineering considerations for implementing a DOL system.

Application: DOL for Lignan Biosynthesis in Yeast Consortia

Lignans are a class of plant secondary metabolites with documented anti-cancer, antiviral, and antioxidant properties [25] [26]. Their complex structures, such as that of the anticancer precursor podophyllotoxin, make chemical synthesis impractical, and their low abundance in native plants—some of which are endangered—creates supply challenges [25] [16]. Metabolic engineering offers a sustainable alternative, but reconstructing long lignan pathways in a single host often leads to metabolic promiscuity, low titers, and accumulation of undesired intermediates [3].

A Synthetic Yeast Consortium for De Novo Lignan Synthesis

A landmark 2025 study demonstrated a sophisticated application of DOL by dividing the lignan biosynthetic pathway across a synthetic yeast consortium engineered for obligate mutualism [3] [14]. This system was designed to mimic the natural multicellular compartmentalization found in plants. The core design principle was to separate the upstream biosynthesis of the key precursor, coniferyl alcohol, from its downstream dimerization and modification into lignan skeletons like pinoresinol and lariciresinol [3].

A critical feature of this system was the use of ferulic acid as a metabolic bridge between the two specialist populations [3]. This architectural choice alleviated the issue of metabolic promiscuity and channeled the flux efficiently toward the target lignans. The study successfully achieved de novo synthesis of pinoresinol and lariciresinol, and further verified the consortium's scalability by producing complex antiviral lignans such as lariciresinol diglucoside [3].

Table 2: Key Lignans and Their Bioactivities Relevant to Engineering Efforts

| Lignan | Natural Source | Documented Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|

| Podophyllotoxin (PTOX) | Podophyllum species (Mayapple) | Precursor to semi-synthetic anticancer drugs (e.g., etoposide) [25]. |

| Pinoresinol | Sesame, Forsythia | Converted by gut flora to enterolignans; anti-inflammatory properties [25] [27]. |

| Lariciresinol | Flaxseed, Linum | Suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis in breast cancer models [25]. |

| Secoisolariciresinol (SECO) | Flaxseed (richest source) | Converted to enterodiol and enterolactone; reduces breast cancer risk [26] [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Engineering Synergistic Consortia

Implementing a functional DOL-based production system requires a structured experimental workflow, from initial strain construction to final co-culture optimization. The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the key stages for creating a mutualistic yeast consortium for lignan synthesis.

Detailed Methodology for Consortium Construction

Phase 1: Pathway Analysis and Modularization

- Identify a suitable pathway intermediate to serve as the exchanged metabolite (e.g., ferulic acid [3] or coniferyl alcohol [3]). This intermediate should be relatively stable and readily transported.

- Split the full biosynthetic pathway into two discrete modules. The upstream module typically covers the pathway from primary metabolism to the chosen intermediate. The downstream module converts the intermediate into the final target product(s).

- Select host strains: Use compatible microbial strains (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) with similar growth rates to prevent one population from outcompeting the other.

Phase 2: Engineering Specialist Populations

- Clone pathway modules: Assemble each module in appropriate expression vectors (e.g., yeast episomal plasmids or integration cassettes) with strong, constitutive promoters.

- Transform specialist strains:

- Upstream Specialist: Engineer to overexpress the upstream module. Knock out genes that divert key precursors (e.g., ARO10 and PDC5 to reduce consumption of aromatic amino acids [16]).

- Downstream Specialist: Engineer to overexpress the downstream module.

- Implement cofactor engineering: To boost efficiency, overexpress genes from the pentose phosphate pathway (e.g., ZWF1) to enhance NADPH supply, a critical cofactor for P450 enzymes [16].

Phase 3: Establishing Obligate Mutualism

- Introduce auxotrophic markers to ensure stable coexistence. For example, engineer the upstream specialist to be MET2-deficient (methionine auxotroph) and the downstream specialist to be LYS2-deficient (lysine auxotroph) or use similar complementary markers. This forces cross-feeding and prevents the collapse of either population [3].

Phase 4: Validation and Optimization

- Validate intermediate transport: Culture the upstream specialist alone and use HPLC-MS to detect the secretion of the target intermediate (e.g., ferulic acid) into the culture medium.

- Assemble the consortium: Co-culture the two specialist strains in a minimal medium that requires them to cross-feed both the pathway intermediate and essential nutrients.

- Monitor population dynamics: Use flow cytometry or selective plating to track the ratio of the two populations over time to ensure stability.

- Quantify product titers: Measure the final product concentration (e.g., pinoresinol) and compare it to the titer achieved by a single-strain control harboring the entire pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents, molecular tools, and strains essential for constructing and analyzing metabolic division of labor systems in yeast, with a focus on lignan biosynthesis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Engineering Lignan-Consortia

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Lignan DOL |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Yeast Strains | Engineered S. cerevisiae with knockouts in essential amino acid biosynthesis genes (e.g., met2Δ, lys2Δ). | Basis for establishing obligate mutualism in the consortium [3]. |

| Ferulic Acid | A hydroxycinnamic acid and key intermediate in phenylpropanoid metabolism. | Used as a "metabolic bridge" exchanged between specialist yeast populations [3]. |

| p-Coumaric Acid (pCA) | A precursor for ferulic acid and other phenylpropanoids. | Fed as a starting substrate to the upstream specialist strain to boost flux [16]. |

| HpaB & HpaC Enzymes | A bacterial two-component enzyme system for efficient conversion of pCA to caffeic acid. | An alternative to plant P450s (C3H) to improve intermediate production in yeast [16]. |

| Phosphoketolase (Xfpk) | An enzyme that splits sugar phosphates, redirecting carbon flux. | Overexpressed to pull flux through the pentose phosphate pathway, increasing NADPH supply [16]. |

| Dirigent Protein (DIR) | A plant protein that guides the stereoselective coupling of coniferyl alcohol to form pinoresinol. | Expressed in the downstream specialist to control the stereochemistry of the lignan product [25] [27]. |

| UGT74S1 | A glycosyltransferase enzyme from flax. | Catalyzes the glycosylation of secoisolariciresinol (SECO) to form its stable diglucoside (SDG) in the pathway [27]. |

| TSI-01 | TSI-01, MF:C14H11Cl2NO4, MW:328.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kisspeptin 234 TFA | Kisspeptin 234 TFA, MF:C65H79F3N18O15, MW:1409.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Metabolic Division of Labor represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving from the optimization of single super-strains to the design of synergistic microbial ecosystems. For complex plant natural products like lignans, this approach directly addresses critical bottlenecks including metabolic burden, enzyme promiscuity, and intermediate toxicity [24] [3]. The successful application of an obligate mutualism strategy in a yeast consortium not only provides a scalable platform for the sustainable production of valuable lignans but also serves as a blueprint for the heterologous biosynthesis of other intricate molecules.

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on dynamic population control to enhance consortium stability and productivity further. The integration of more sophisticated transport engineering to facilitate intermediate exchange and the application of advanced modeling to predict optimal population ratios will be crucial. As synthetic biology tools continue to mature, the rational design of multicellular microbial systems with specialized divisions of labor will become an increasingly powerful strategy for chemical production, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in a bio-based economy.

Building Obligate Mutualism: A Step-by-Step Guide to Consortium Assembly